20,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

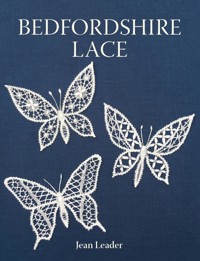

Bedfordshire lace became popular in the fashions of the second half of the nineteenth century because of the beauty of its bold-open designs, often with elegant floral motifs, and it continues to fascinate and captivate lacemakers today. This practical book is dedicated to the novice and experienced lacemaker wishing to learn these techniques so as to realize this elegance for themselves. Information is given about the equipment needed for bobbin lacemaking, how to make a pricking (the pattern on which the lace is made), and how to wind thread on the bobbins. Instruction explains how to work cloth stitch and half stitch, plaits, windmill crossings, picots and leaf-shaped tallies, and how to finish a piece of lace. There is a series of twenty-six patterns, some traditional and others designed more recently. These are supported by instructions, photographs and diagrams. The patterns include small motifs, edgings - some with corners for handkerchiefs - butterflies and, finally, three exquisite collars.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 163

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

BEDFORDSHIRE LACE

Handkerchief edging worked by the author from a draft in The Cecil Higgins Art Gallery & Museum, Bedford.

BEDFORDSHIRE LACE

Jean Leader

First published in 2021 by The Crowood Press Ltd Ramsbury, Marlborough Wiltshire SN8 2HR

This e-book first published in 2021

© Jean Leader 2021

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.ISBN 978 1 78500 819 1

Acknowledgements I would like to thank my husband David for all his support and in particular for his help in re-drawing many of my diagrams, my friend Gilian Dye for reading my first drafts and making useful suggestions for improvement, and The Lace Guild for a bursary to study the Rose Family Sample Book. Thanks are also due to the lace teachers and authors who have inspired and encouraged me – Barbara Underwood in particular, but also Mo Gibbs, Pamela Nottingham, Pamela Robinson and Margaret Turner, whose selection of patterns published by Ruth Bean first made me fall in love with Bedfordshire lace.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Bedfordshire lace developed in the mid-nineteenth century, partly in response to the fashion trends of the time that favoured bolder laces. Together with similar bobbin laces from other parts of Europe, it was also as a reaction to the ever-increasing threat of competition from machine-made lace. Bedfordshire is one of the three counties that make up the East Midlands lacemaking area of England, the other two being Buckinghamshire and Northamptonshire, but despite its name this lace was made in all three counties and neighbouring villages. Bobbin lace had been made in this area since the late sixteenth century where it was organized as a cottage industry, with the lacemakers working in their own homes using patterns and thread supplied by lace dealers. Periodically the dealers would collect the finished lace and arrange for its sale.

The success of the industry, and the style of lace made depended very much on whatever was currently fashionable. The beginning of the nineteenth century had been a successful time for the East Midlands industry with fashions favouring the relatively simple Bucks Point laces with net grounds and limited decoration that were being made there. This was also a time when the Napoleonic Wars limited the import of European laces. However, this success was not to last – in nearby Nottingham machines were being developed which could reproduce the bobbin-made net perfectly. By the 1850s lace machines had developed at such a pace that they were able to produce lace with both net ground and decoration that was difficult to distinguish from hand-made lace. In order to survive, the hand-made lace industry needed something new that could not be reproduced by machine and was also fashionable. The answer was a lace where the pattern motifs were joined by bars of plaited thread, rather than a net ground; this was initially called Bedfordshire Maltese. The use of ‘Maltese’ in the name was no doubt to benefit from the publicity that this style of lace from Malta (itself based on old Genoese lace) had received when exhibited at the 1851 Great Exhibition in London. The same style of lace was also made at the lacemaking centres of Mirecourt and Le Puy in France and in a similar marketing ploy this was given the name Cluny after the Musée Cluny in Paris, where seventeenth-century Genoese lace was exhibited. What all these laces have in common is that the designs include plaited bars, often decorated with picots; small woven blocks known as tallies; trails worked in cloth stitch; other design elements in cloth stitch or half stitch, sometimes embellished with overlaid or raised tallies.

How the lacemakers learnt to make this new style of lace does not seem to have been recorded. Were they simply given a sample with the new pattern and left to work it out for themselves? Or did the lace dealers send someone to show them what to do? However it happened the lace was soon being produced in quantity. Much of this lace was insertions and edgings – there is a sample book dating from the 1860s that belonged to the Rose family, lace dealers from Paulerspury in Northamptonshire, which contains over 600 unique patterns ranging in width from under 2cm to over 5cm (this book is now in the care of the Lace Guild Museum). Larger items such as collars, cuffs, head pieces and wide flounces, often with elaborate floral designs, were also made. Some of these patterns are known to have come from local designers of whom Thomas Lester is probably the best known, but the designers of the many insertions and edgings are anonymous.

Unfortunately for the lacemakers, the machine-made lace industry did not stand still and before long even this new style of lace could be produced by machine. By 1900 most of the hand-made lace industry in England had disappeared, and it is only the interest and dedication of a few individuals that has ensured knowledge of lacemaking techniques and patterns has been preserved for the benefit of all the lacemakers who now enjoy bobbin lacemaking as a fascinating hobby.

A selection of Bedfordshire lace edgings.

CHAPTER 1

EQUIPMENT, MATERIALS AND GETTING STARTED

All bobbin laces are made with multiple threads, each wound on to a separate bobbin, and are worked on a pattern, known as a pricking, attached to a firm pillow. Stitches are worked with two pairs of bobbins (four threads), and are held in place as they are made with pins pushed through the pricking into the pillow. When the lace is finished it is released from the pillow by removing the pins. The style of the pillow and bobbins used can vary between lacemaking areas, while the size of the pins and the thread used will depend on the style of the lace being made.

The same basic stitch movements are used in all bobbin laces, but how the stitches are arranged varies from one type of bobbin lace to another. Bedfordshire is one of the continuous bobbin laces; that is, one that starts with all the threads needed for the full width of the lace. These threads remain in use throughout and the lace is worked in one direction.

Handkerchief edgings (Patterns 4, 8, and 13).

PILLOW

In the nineteenth century, Bedfordshire lace would have been made on a large bolster pillow tightly packed with chopped straw, and supported on a stand known as a ‘horse’ or ‘maid’. Although good to work on, this style of pillow is hardly practical for lacemakers today who want to take their pillows to lace group meetings and courses. Pillows now come in a variety of sizes and shapes – round, square, rectangular, with movable blocks or rollers, and can be either made from polystyrene (Styrofoam) or packed with chopped straw.

A basic pillow suitable for many of the patterns in this book can be made from a piece of high-density polystyrene (Styrofoam) about 40cm (16in) square and 5cm (2in) thick, covered with suitable fabric.

A round pillow, sometimes known as a cookie pillow, is useful for working small motifs. It can also be used for working long lengths but to do this the lace has to be lifted and moved up to the top of the pricking at intervals, as has been done with the narrow edging being worked on this pillow.

A pillow with movable blocks is often a better option for working long lengths, handkerchief edgings, collars or other large patterns than using a very large pillow. Where to place the pricking on the blocks needs to be planned beforehand but once that is done, it is then straightforward to move blocks so as to bring the working area into a convenient position.

Pillows with rollers are ideal for working long lengths. The pricking needs to be of complete repeats with the start and finish butted together, so it may be necessary to pad the roller for a good fit. The lace on this pillow is being worked without a card pricking – instead the squares of the fabric are used as a guide for placing the pins.

Whatever the shape, a pillow should be firm enough to support the pins and a suitable size for the pattern being worked – the bobbins should not dangle over the edge and the working area should be within easy reach. All the pillows illustrated are about 40cm (16in) wide. The pillow should be covered with a plain fabric in a dark colour. Two cover cloths of a similar fabric are needed, one to cover the lower part of the pricking under the bobbins and the other to cover the pillow when not in use.

BOBBINS

Most of the nineteenth-century East Midlands lacemakers would have used slender bobbins decorated with a ring of beads known as a spangle, although thicker bobbins without spangles, now known as South Bucks bobbins, were also used. However, the lacemakers making similar lace in France and other parts of Europe all used plain wooden bobbins of various shapes. It is better not to mix spangled with unspangled bobbins but otherwise the choice of which to use depends on personal preference.

From left to right: Nineteenth-century South Bucks bobbins, nineteenth-century East Midlands spangled bobbins, contemporary East Midlands spangled bobbins, French, Spanish and Maltese bobbins.

Most bobbins are made of wood but bone, plastic, aluminium, and even glass have been used. East Midlands spangled bobbins were often decorated with names or details of special events, a tradition that has now spread all over the world.

PINS

For the patterns in this book, fine pins, 0.50 to 0.55mm in diameter and 26 to 30mm long, in brass, nickel-plated brass or stainless steel are suitable. If the patterns are enlarged for use with thicker thread, it is better to use pins 0.65 to 0.70mm in diameter.

Stainless steel pins and a pin cushion.

SCISSORS

Small, sharp scissors are needed for cutting thread. Larger scissors are used for cutting paper and card when making prickings.

Scissors: a pair for cutting thread, and another for paper and card.

THREADS

Bedfordshire lace can be worked with cotton, linen or silk threads. For the initial patterns in this book I used Madeira Tanne 30, DMC broder machine 30, Gütermann silk S303, or single strands of 6-strand embroidery floss. Later patterns where the pinholes are closer together require finer threads, and for these either Madeira Tanne 50 or DMC broder machine 50 was used. These are all 2-ply threads apart from the silk, which is 3-ply.

A variety of threads that can be used for working Bedfordshire lace.

Linen threads can also be used, although they are usually not quite as smooth as cotton and silk. For the initial patterns either 80/2 or 90/2 linen would be suitable but the finest linen thread available today, 140/2, is not quite as fine as the Madeira and DMC 50 cotton threads so the patterns might need to be enlarged a little. These are all 2-ply threads, but because the numbering system for linen thread is different, the numbers do not match those of the equivalent cotton threads. Threads of a similar thickness can be substituted for any of those I used.

PRICKING

The prickings used by the nineteenth-century Bedfordshire lacemakers would have been made with parchment, skin from cattle or sheep that had been treated to give a smooth surface, and any pattern markings needed would have been added with ink. They were usually about 15in (38cm) long and had fabric tabs stitched to both ends. These tabs, known as eches, were used to pin the prickings to the large bolster pillows.

From left to right: card, pattern and adhesive film; two styles of pricker.

Today prickings are made on stiff card. To avoid the task of adding pattern markings, the paper pattern is stuck on stiff card and covered with adhesive film in a colour that contrasts with the thread to be used. Then the pricker (a No.8 needle in a pin vice or wooden handle) is used to make the holes.

PIN-LIFTER AND PIN-PUSHER

A pin-pusher is helpful for pushing pins flat to the pricking to keep them out of the way, and a pin-lifter helps with pulling out pins once the lace is finished. They can be separate items or as single one with both functions. The metal end of the combined lifter and pusher illustrated has a concave indentation (the pusher) with a rim (the lifter).

Top: Pin-lifter; Bottom: Combined pin-lifter and pusher.

CROCHET HOOK OR LAZY SUSAN

A crochet hook or a Lazy Susan is used when joining the end to the beginning of a piece of lace – how to use them is explained in Chapter 2. A Lazy Susan is a threaded needle with its point in a handle. The needle can be bent, as in the one illustrated, or can be a flexible beading needle.

Top: 0.6mm crochet hook; Bottom: Lazy Susan.

LIGHTING AND FURNITURE

Making sure that you are comfortable while making lace is as important as choosing your pillow and bobbins. When sitting in your chair you should be able to rest your feet flat on the floor – if not, use a foot-rest. What about the height of your table or pillow-stand? Ideally your pillow should be at, or just below, elbow height. You may also want to tilt the back of your pillow upwards slightly. You need to help yourself to stay comfortable too – stand up and stretch or walk around every now and then.

You also need to think about the lighting of any area where you may be working. Good daylight is wonderful but for working in the evenings or on dull days you may need extra light. A desk lamp may be sufficient but there are also specialist craft lights, often with magnifiers attached, which may be more suitable. Be kind to your eyes too by looking up from your lace and focussing on something further away from time to time.

MAKING A PRICKING

The step-by-step instructions show making a pricking using coloured adhesive film. Grey is a useful colour as it is provides a good contrast with both white and coloured threads. Light blue is also good, but not for blue threads, and orange is often used in Spain. If coloured adhesive film is not available, photocopy the pricking on to coloured paper (again choose a colour that will show up the thread) and cover it with clear matt adhesive film to protect the worked lace from the photocopy ink.

Prickings can also be made without coloured adhesive film as they were before it became available. To do this use drawing pins to fasten the paper pattern on top of the card on a cork board and prick through each dot (as in step 3). Then remove the paper pattern and use a fine waterproof drawing pen to add the lines and other markings to the pattern of pinholes (do not use pencil or ballpen which could rub off on the lace).

1. Cut a piece of card larger than the paper copy of the pattern and stick the paper pattern to the card, leaving a margin all round.

2. Cut a piece of matt adhesive plastic film the same size as the card in a colour that contrasts with the thread to be used. Stick the plastic film on top, being careful not to crease it or leave air bubbles.

3. Place the ‘sandwich’ on a cork board and use the pricker to prick through each dot. Hold the pricker upright and make sure that the point of the needle goes through the dot and not to the side of it.

4. Check that no dots have been missed by holding the pricking up to the light. The arrows indicate where dots were missed.

A pricking made without coloured adhesive film. It is a good idea always to record the source of the pattern, thread used and number of pairs needed on the pricking.

WINDING BOBBINS

1. Hold the bobbin in your right hand and, holding the end of the thread against the bobbin, take the thread under the bobbin and back over the top towards you until the end is secure. Then wind on the thread by turning the bobbin away from you. Look down the bobbin from the top – the thread should be wound clockwise.

2. When enough thread is on the bobbin, make a hitch to stop it unwinding – hold the bobbin in your right hand and take the thread round your left thumb from front to back, bring the head of the bobbin up into the loop, remove your thumb and pull tight.

Winding bobbins.

3. Cut off enough thread for the other bobbin of the pair and wind it on in exactly the same way and make a hitch. Leave about 20cm of thread between the bobbins. The bobbins may look as if they are wound differently, but that is because you are seeing the left-hand bobbin from the opposite side.

Shortening and lengthening the bobbin thread.

To lengthen the thread while working hold the bobbin in your right hand (with the thread slack) and turn the bobbin towards you as shown in the upper section of the illustration. To shorten the thread hold the bobbin in your left hand, lift the loop of the hitch with a pin and turn the bobbin towards you as shown in the lower section of the illustration.

A common problem is that the hitch slips and the bobbin thread gets longer and longer. This can happen if the hitch was made incorrectly or the thread was wound on anti-clockwise rather than clockwise. Take off the hitch, hold the bobbin in your right hand and turn it away from you. Does this unwind even more thread or does the thread wind back on to the bobbin? If even more thread unwinds it must have been wound on in an anti-clockwise direction and you can either unwind all the thread and wind it back on in a clockwise direction or make the hitch using your right thumb instead of your left.

There is nothing wrong with winding the thread in an anti-clockwise direction, but having all the bobbins wound in the same direction is best as lengthening or shortening thread will be the same for all of them – you would also need to reverse the directions for these if threads are wound anti-clockwise.

Thread wound anti-clockwise with hitch made using right thumb.

Making a double hitch.

If the hitch slips even though the thread is wound clockwise, something was wrong with the way you made the hitch and you need to try again. If you definitely made the hitch correctly and it still slips, it may help to make a ‘double hitch’ – bring the head of the bobbin up through the loop for a second time before pulling tight.