Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Bedford Square Publishers

- Kategorie: Ratgeber

- Sprache: Englisch

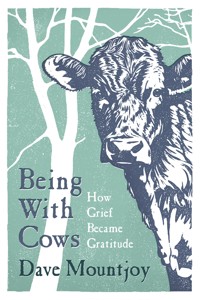

'An unexpected sanctuary from grief... a tonic for the soul' Mary Costello An intensely transformational story of how grief became gratitude in the presence of a humble herd of cows. Being With Cows details the incredibly moving story behind the tragic death of one man's brother and how his personal quest for inner healing came to him unexpectedly on his organic farm in the French Pyrenees. A remarkably powerful yet heart-warming story, Being With Cows pays homage to Life's unending compassion and insistence that in the very centre of all things, lies pure and untainted simplicity. Through a deeply tangible sense of gratitude, it tells of how tragedy can be overcome through the healing power of nature. The book contains 12 original illustrations of cows by Sean Briggs©.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 256

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For Judith, you shining Saint of a spotless Casta.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Prologue

1. Direction

2. It’s all about the cows

3. Natural practice

4. The Maharshi

5. From tears to transformation

6. Reaching out

7. Retreats

8. Momentum

9. The BBC

10. Cowfulness – the art of farming mindfully

11. Pastures new

12. Thank you

Epilogue

The Cows

Footnotes

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Prologue

I love animals. It’s as simple as that really. Above all else I love them for the way in which they remind me of quietness; they seem to have an existence largely untroubled by thought. They are as they are, without need for reflection or introspection.

As far as I’m aware and with increasing conviction, I can say that theirs is a life lived mindfully. They are natural experts, born to be and not to think about being. Perhaps they are the lucky ones?

Perhaps I have been lucky myself, privileged to be able to spend so much precious time in their company, the cats and dogs and cows and calves, puppies and childhood guinea pigs?

I must have been in my mid to late twenties, still living very happily at home with mum and dad, when a family friend brought three jackdaw chicks to the house. I can’t say why but somehow their arrival made me think of our own family brood, especially my two brothers Pete and Cork – one chick for each of us. The bringer of such unexpected innocence into our midst was a local woodcutter and genuine salt-of-the-earth material. He had found the three little waifs still in the nest, a relatively rough old affair of twigs and bits and pieces that the parents had found round about. He’d been asked to clear the chimneys of a rambling old country house of such unwanted things, but hadn’t had the heart to knock the little ones on the head.

Knowing that our family was well known in the area for taking in injured wild birds or animals, he had decided to bring them, very much alive and kicking, to us. We happily took them in and, looking at their soft black downy feathers, we guessed that they were a couple of weeks old at the most. Jackdaw chicks fledge at around four to five weeks and therefore with at least two or three weeks until they could be returned to the wild, we popped them in the quietest shed in the garden, out of harm’s way from magpies, jays and the host of neighbouring cats. Their new nest was an old fruit box full of straw and they seemed to take to it immediately without any fuss at all.

The next days in their company can only be described as an absolute delight. Gorging themselves on bread and milk as often as they liked, the chicks grew strong and incredibly confident. What amazed us all was the intimacy that they were capable of expressing. Once their tummies were full, they would hop on to the nearest hand, bounce their way up the arm and settle so comfortably in the crook of the chosen one’s neck. When it was my turn to receive such a blessing, I would go into raptures as a small but inquisitive little beak would ever so softly begin exploring the inside of one of my ears. What an absolute privilege to share such moments with such beautifully alive little beings.

When the shed door was finally left open for good, the fledgelings spent the first few days in and around the garden. They would still come to be fed and were happy to perch on the head, hand, arm or shoulder but little by little they began to edge further afield. The day came, not long after, when they seemed to have flown the nest for good. For several days I would go out into the field, calling out to them in the hope that they would return for a final goodbye. It must’ve been a month later, as August gave way to September, that I thought I would try just one more time. Walking right up to the far edge of the field, I thought I could hear several jackdaws chattering away in some old oaks a couple of hundred yards away from where I was standing. ‘Jack, Jack, Jack, come on then Jack, come on then.’ After five minutes without response, I turned to go back to the house. I hadn’t really expected anything to happen but thought it was worth a try. As I reached the middle of the meadow, something made me turn and look back towards the trees. To my utter amazement and joy, I saw three young jackdaws heading directly towards me. Stretching my arms out as I had done in the garden several weeks before, I waited to see what would happen. Barely able to breathe with the excitement that had gripped me, I continued to hold out my arms until one after another, those beautiful black forms just swept right in and landed with perfect poise and precision on my outstretched limbs.

Even after so many years, I have yet to find the words to adequately describe the sense of belonging and trust that I experienced during those moments. The intelligence behind their strikingly light blue eyes, the outlandish way in which they hopped from my head to shoulders and back again had me feeling that I was in the presence of an expression of pure love. I was lit up inside, totally dissolved in the sheer naturalness of their antics. Every single comic twist of their blue-black heads, the jester-like way in which they peered into my disbelieving face, brought a confirmation of nature’s capacity to stir up very deep feelings of both gratitude and humility.

After this final goodbye, I never saw the jackdaws up close again. It didn’t matter. What they had gifted me was precious beyond words. That they were successfully returned to the wild was the icing on the cake. To have tried to have kept them as pets would have spoken of attachment and it simply couldn’t be that way.

Experiences such as this one have ingrained in me a reverence for the natural world. Once a refuge, I now see it as the purest expression of Life itself. There is something inherently whole and revealing to be found among the trees and meadows and streams. Revealing in the sense that with patience and commitment, the dedicated searcher can come to realise the futility of thought and foolishness of a reliance upon its flimsy fiction of a world.

By its very nature, the natural world provides a constant reminder that nothing in this appearing world can lay claim to any sort of permanence. A fallen tree that rots slowly back into the forest floor, the thousandth pheasant that day to be levelled into the unyielding tarmac of a busy road or even the side of an immovable mountain that slid to the valley floor are all testament to the constant change and ebb and flow of Life’s great singular movement.

However, behind the façade of apparent form, there lies the very essence of what we mistakenly call our lives – namely the source of absolute quietness, the unmoving and unmovable Is-ness of being that exists as the very heart of mindfulness.

When I look quietly into the liquid eyes of any of the cows we share the farm with, I am immediately reminded of an inescapable sense of stillness. There is something so uncomplicated in the bright-shine which calls me back through memory and thought itself, until the very idea of a separate me becomes nothing more than a figment of a limited and ultimately finite imagination.

The red and roe deer, the wild boar, pine marten and chat forestier are but a few of our nearest neighbours in this little upland chunk of paradise. It is to them we look for inspiration. It is they who remind us of our place in the world and that quietness really is king. While it’s a treat indeed to see them going about their business, their presence is most appreciated from an interior perspective.

The blue tit, wren and tiny goldcrest struggling to survive in the hungry months of winter speak to me of courage. The thrushes who start all over again when late frost takes their featherless brood are reminders of determination. Even the stream in the valley bottom, gurgling in spring’s rain-filled generosity and dry under cloudless skies of August heat, nudges me into accepting the fleeting nature of what appears to be so solid and reliable a world.

CHAPTER 1

Direction

‘Sometimes in the wind of change we find our true direction.’

ANON

For several years, beginning in 2006, I became a regular visitor to the Findhorn Foundation (a spiritual community founded in the late 1960s) in northern Scotland, hell-bent on making the absolute most of having no other commitment in life but that of self-discovery. Yes, it IS a commitment.

It was on what was to be the final journey north in 2012 that this solo voyage came to its natural conclusion, for during those late-summer days along the Moray Firth, I met the woman who was to become my wife.

‘Hello. I’m Diana. I come from Barcelona,’ and then several days later, ‘Where have you been? I was looking for you.’

When the workshop ended, we agreed to meet up in Spain, first of all in Avila and then continuing across the French Pyrenees, from the Atlantic to the Mediterranean coasts. Soon after meeting, we had discovered a mutual desire to live in the Pyrenees and it was with this in mind that we travelled. For several weeks, we meandered back and forth across the border between France and Spain. Both of us felt most at home and inspired by the area on the French side known as the Couserans, in the department of the Ariège. Perhaps the wildest part of the French Pyrenees and still populated by a small number of European brown bears, the steeply carved valleys, majestic beech woodlands and snow-capped mountain peaks cast a deeply intoxicating spell on us.

There is something so very humbling and invigorating to be found in the presence of such mountainous majesty. For a while, we explored without thought of making home, content to simply be there, grateful that we had time to wander at leisure.

At the beginning of 2013, as the first real snow of winter made a wonderland of both mountain and valley, we rented a small place right in the heart of the Couserans. By now we were sure that it was here or round abouts that we wanted to live. There was a sense of fertility, of lush greenery and the freshest of air that was somehow lacking once we stepped outside the mountains themselves. Even the Piedmont, the foothills and rolling hills around, still breathtakingly beautiful and deeply wooded, failed to ignite in us the fire we that felt beside those rocky peaks.

Using the rented flat as a base, we searched and we searched, from cottage to ruin and everything in-between, yet as Life would have it, the place that for both of us ticked all our many boxes, failed to materialise. Too much traffic, too expensive or not enough land, there was always something that prevented both of us from saying a definite yes.

Frustration. Arguments: tantrums and threats to abandon the whole adventure.

We did give up for a while, spending the spring of 2013 in Morocco, laying the foundations of a relationship that was to be sorely tested in the months and years to come.

Yet we never gave up completely. Something kept us hanging in there, trusting, trusting that all would eventually be well.

Landing back in south-western France the following autumn, we started to look further afield and after much deliberation, decided to rent some land and eco-cabins near the market town of Saint-Girons. At the end of a twisting three-mile track, if it was isolation we wanted, we had it in plenty. Two lovingly crafted natural buildings, woodland and meadow and a view that seemed to stretch to the ends of the world. The sunsets were simply spellbinding. No mains water, no inside toilet and most definitely no Internet, via landline, signal or any other means. It was what you might call interesting!

Our plan at the time was to develop a glamping business on the land. We were convinced that the beauty of the landscape and in particular the staggering views west to where the sun dipped down would be enough to have guests pouring in. Two yurts were ordered from an English couple who had settled nearby in the mountains. Diana began to make beautiful flyers and a website for what we hoped would become a thriving enterprise.

But Life! Things just happen as they do, regardless of ideas or carefully crafted plans. Diana became pregnant and the more I worked on the land, preparing things for the eventual opening of the glampsite, the more I was bothered by the fact that we didn’t actually own it. I felt restricted, somehow, subject to the whims of the owner’s plans and preferences. As the autumn gave way to winter and snow blocked the track for weeks at a time, that sense of not being Lord and Lady of our own manor really began to nag away at me. I couldn’t find the confidence I was looking for to reassure me that all the investments we were making in the place, beautiful as it was, would eventually bear fruit.

At the beginning of 2014, I began looking again for a property that would allow us to refine and then develop our ideas into a concrete plan and vision. Mirepoix, a small town in the very north-east of the department, was not somewhere we had passed through before. Well out of the mountains and with more of a Mediterranean climate than the freshness of Saint-Girons and the Pyrenees further west, we had not considered that such a place could be somewhere we could settle and thrive.

So much for plans and deeply held desires. One look at the view from the top of some organic land we went to see nearby was enough. ‘This is it!’ I said to Diana. I didn’t need to think about it. It would have been such a shame to think when faced with such a view – a wave of forested greenery whose foaming crest seemed to come crashing down at the feet of the mountains themselves. It was just so complete and staggeringly beautiful that to think would have been akin to some kind of blasphemy and I knew without a shadow of doubt that the search had come to its end. Diana, however, wasn’t completely convinced, and even the spontaneous jig of delight with which I celebrated did little to soothe her worries. Although the 75 acres were indeed picture-postcard perfect and two beautiful wooden barns were included in the sale, the fact of the matter was that there was no house to live in. Where would we stay, she asked? Would we have to rent nearby? How much would that cost? At the time, we couldn’t afford the extra burden of having to rent somewhere on top of the actual purchase of the land.

I listened to her concerns, her genuine worries, the proper questions to be asked by a heavily pregnant mother-to-be, but I just couldn’t pull my eyes from the view. Something was insisting. It wasn’t stubbornness or even that I’d fallen so quickly in love with the land, but something not easily definable that had me rooted to the spot. ‘This is it,’ I repeated. ‘We have to take the plunge and here is where we dive in.’ We talked for a while about risk and the more we gave voice to our feelings, any lingering doubts that I may have unknowingly had about the place evaporated. It wasn’t a case of trying to persuade Diana or convince her that everything would be OK. I couldn’t even offer such meagre words of comfort. As I saw it at the time, the greatest risk lay in denial, in a refusal to listen to what something beyond the chit-chat patter of thought was telling me. As long as I kept this in mind, there was nothing else to say. The quietness I was experiencing said it all and words would only serve to get in the way. Within an hour or two, on the way back to Saint-Girons, it seemed like Diana had intuited this rock-like refusal to budge as a sign that risks were for the taking. She spoke very little but gave her consent to the plan.

The first days we spent on the land are difficult to describe. It was mid-April, only two short months from that first heady visit, yet now that spring was in full spate, the whole landscape had changed. Winter’s stark scrawl had swelled to bursting point, a humid riot of unfolding green that spoke of warmth and the promise of new things to come. Several species of orchid blessed the meadows with their presence, thousands of them turning whole acres into places of holy communion. There were wildflowers everywhere, in the woods, the meadows and skirting the sides of the stream. From the top of the land, the Pyrenees stretched out in an unbroken chain, sometimes smooth and whale-backed, others jagged broken-toothed affairs, yet all still snow-capped at the peaks.

Visually speaking, I was amazed at the transformation that had taken place since the last time we’d visited: amazed and deeply delighted. But what really got me was the sheer mass of sounds that now filled the valley so full of vitality that the air itself seemed to crackle and hum. From crickets to cuckoos and hardy cicadas to the first flocks of swifts screeching happily overhead, the air fizzed with a tangible sense of awakening, of creation cranking sweetly back into action after months of heavy slumber. The jewel in the crown for me was the chorus of croaking frogs who nightly lulled me into some of the deepest and cleanest of sleeps I could remember. Only in Africa had I heard such intense expression, the season singing itself into being.

As orchestras go, this surely topped the lot and several times during those first few days, my gratitude at being brought to such a place brought tears to the eyes. I felt so much at home that it seemed like the landscape was merely an extension of my own body.

Where had the risk been? If fortune favours the brave, then already we had been repaid for our trust in the process in ways that made money seem such a poor indicator of wealth. These were real riches, breathable vibrating outpourings of nature’s greenest gold.

Such was the depth of the feeling I had that all was unfolding as Life intended that it was no surprise when the previous owners offered us a wooden chalet to live in free of charge, on the edge of the land we’d bought from them. From all around came confirmation that as mere pawns on the chessboard of Life, we were being moved into very favourable positions.

As the first week in our role of new guardians of the land came to a close, Diana and myself began to settle into some kind of routine. In between mealtimes, we would explore the farm, immersing ourselves in all it had to offer. I was thrilled to find that we shared the land with such a rich array of wildlife: foxes, badgers, wild boar, red and roe deer and even the elusive genet. We also kept an eye out for potential yurt sites because at that time glamping was still the heartbeat of the project.

Several weeks passed by in an excited blur of discovery. Spring gave way to summer and with it came the sense of something reaching its peak. The meadows were awash with colour and the migrant birds a constant source of wonder: bee-eaters, hoopoes and door-sized vultures circling high overhead had me in raptures. It was everything I could have ever wished for, a veritable Aladdin’s Cave of natural treasure, and it was into this mix that they first found their way into the conversation.

I was sitting one evening with Francis, the previous owner of the land and now our nearest neighbour. My French was at the very best what you might call minimal, but I felt so warm and relaxed in his company that the words didn’t seem to really matter at all. When I’d told him a few weeks before that I’d seen a sheep standing high up on the roof of the barn, an impressive forty feet from the ground, he’d taken it all in his stride, acting as if it was the most normal thing in the world. I can’t remember what I’d actually wanted to tell him but whatever was lost in translation only helped to cement the bond between us.

On this occasion, he had asked me about our plans for the land and, in particular, where we wanted to live in the long-term. The chalet, as convenient as it was, was at best a glorified shed. I tried to tell him that, as yet, we hadn’t given the matter serious thought, so intent were we in getting the glamping business up and running. Without beating around the proverbial bush, he suggested that one of the wooden barns that he himself had built was ripe for conversion into a beautiful home. He also told me, with an unmistakable glint in his eye, that the best way to go about getting permission was to become an agriculteur,a farmer of one sort or another, whose activity required a permanent presence on the land.He and his wife Flo had followed the very same path in order to get planning permission for their incredible off-grid farmhouse.

Having spent most of my childhood on my mum’s family cattle farm, I was immediately comfortable with the idea of having some livestock around, even if the rapidly evolving plan had them pencilled in as mere stepping-stones towards the conversion of one of the barns. Animals hadn’t featured at all in any of our previous discussions, but now that a seed had been planted, I quickly warmed to the idea. I even found a quote that seemed to sum up quite perfectly this unexpected change in direction: ‘Every now and then one paints a picture that seems to have opened a door and serves as a stepping-stone to other things.’ At the time, Pablo Picasso’s words were interpreted with a home in mind. The picture I envisaged was of a small scattering of animals, enough to receive the planning permission, but nothing more. Little did I know quite how prophetic the great master’s words would turn out to be.

Not sheep or goats or pigs and not fruit or vegetables either, but cows. It had to be cows. They were the lifeblood of mum’s farm and I’d grown up in their company. Chasing, being chased, feeding, bleeding and at times trembling with fear, my experience of life at a young age was very much coloured by their cloven-hoofed presence. When Diana and I had taken Francis’ suggestion to heart and agreed that I would register as an official exploitant agricole,it seemed that I’d come full circle, returning, however unexpectedly, to my roots. I was quietly happy that events had taken such an unimagined turn and secretly content that it should be with cows that we moved our project forward.

CHAPTER 2

It’s all about the cows

‘Cows are amongst the gentlest of breathing creatures; none show more passionate tenderness to their young when deprived of them; and, in short, I am not ashamed to profess a deep love for these quiet creatures.’

THOMAS DE QUINCEY

The first three heifers arrived in January 2015. On a bitterly cold day, Diana, myself and Gabi, our gurgling six-month-old son, fetched them from a beautiful farm high up in the foothills of the French Alps, near Gap. I don’t know what it was that had persuaded me to go for Galloways, a hardy ancient breed from the Scottish borders, and to drive so far when the landscape around Mirepoix was sprinkled with an assortment of cattle farms. The fact that I didn’t question such an apparently illogical decision was an early indication of just how deeply the cows were going to affect me. It seems that their non-thinking presence was already beginning to exert a powerful influence, and that their own quiet version of logic ran along very different lines to my generally accepted definition of the word.

Once we got them back to the farm, everything began to change, immediately. I had been excited about creating the glamping business. The prospect of balancing the books by sharing such an idyllic tucked-away piece of living Pyrenean tapestry was something I felt good about. We’d already built the wooden platforms on which the yurts were to be sited and had started work on the toilet and shower block. But with the cows came something of a different quality, more subtle by far yet somehow still earthy and wholly organic.

The idea for the glamping site had come through a series of brainstorming sessions, in which Diana and I had jotted down a mass of thoughts, covering sheet after sheet with everything ranging from fears and phobias to ambitions and the way we wanted to live.

Not a single word was ever written about animals, cows included, but now that they were here, well, I might as well have taken the biggest marker pen I could find and crossed out almost everything I’d previously agreed to. They hadn’t been part of any mind map, simply because, as I was soon to discover, they operated outside what I normally considered to be the mind – the world of thoughts and mental activity that dictated the rhythm of virtually every waking moment.

For the first six weeks, Isi, July and Valentine, as the Galloways were called, were kept in one of the barns that we hoped their presence would help us convert into a home. It was love at first sight and I delighted in taking Gabi with me. I would sit on a bale outside their pen with sleeping beauty in my arms. It was a sheer delight to be sandwiched between two such slices of wholemeal goodness. If Diana took Gabi to see her family in Spain, I would sit there for hours, mostly free of thought and content to be breathing the same air. They fascinated me and made me laugh. Above everything else, they made me smile in much the same way that Gabi did. There was an innocence about them, an honesty that I found highly seductive, and I became, I suppose, an addict of some kind, dosing up on a daily fix of bovine benevolence.

The more time I spent with them, the more I came to know their characters. Valentine was clearly the boss. She was first to each pile of fresh hay and the least timid of the three. Isi and July seemed tied equal second. Even though they were so few in number, I was amazed at their acceptance of this social structure and that for them it was simply the natural order of things. Perhaps that was the first real insight they gave me – that acceptance is a key to the unlocking of many quiet doors. I could see that the hierarchy to which they conformed allowed them to exist in relative harmony, even in such a confined space as the barn. During those early days, I didn’t see them as teachers, yet simply by being themselves, they imparted a wisdom that I couldn’t help but absorb.

It was during another conversation with Francis in my mangled French that I first came to hear of the Casta, a fabled breed of cattle that came originally from the very heart of the French Pyrenees. Surly, stubborn and difficult to do business with, they carried a reputation of non-compliance and barely concealed rebelliousness. He told me that he’d toyed with the idea of keeping a few Casta, a couple of mothers who he could milk by hand or oxen, perhaps, with whom he could work in the forest, pulling out trees he’d felled in inaccessible places. He also wanted to help save them, as the breed had become critically endangered since the modernisation of agriculture took hold at the end of the Second World War.

I was intrigued with what he told me, and that very evening I took what proved to be the first steps into what might be called the Castaverse, a journey from which I’ve yet to return. Within minutes of typing their name into the search box of Leboncoin, a French version of eBay, I discovered that there was a whole herd for sale just 20km away from the farm. Coincidence? No mate, no such thing. I laughed as I read through the advert: a fair price, organically certified and ready to go immediately.

A week later, on another cold and sleety Pyrenean day, we slowly snaked our way along an impossibly twisting lane that meandered this way and that through some forgotten backwater of the foothills. On arriving at the farm, we were taken straight into the gloomy, ill-lit shed that contained what seemed at first glance to be a swirling nervous mass of hoof and horn.

A swarm of frightened bees came to mind, flashing out their barely concealed fear in a series of rapid, reactive movements. The farmer was all smiles and full of good humour, yet the twenty or so young heifers that he had for sale reflected something far less welcoming and warm.

We stood for some time just looking into the pen. For such a cold, murky day and in such poorly lit conditions, the atmosphere inside the shed was surprisingly loaded. The constant skittishness of the Casta acted like some kind of dynamo or generator, filling the air with a very raw and unpredictable energy.

Several times I thought some of the youngsters might take flight and sail clear over the gates that kept them locked inside. It was almost painfully obvious that they weren’t used to being so contained and some of the faces showed sure signs of distress.