Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

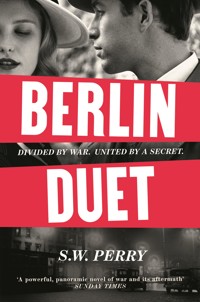

'A POWERFUL, PANORAMIC NOVEL OF WAR AND ITS AFTERMATH' SUNDAY TIMES 'What a love story' Elizabeth Buchan 'Gripping and heartfelt' Elisabeth Gifford 'Entirely convincing and authentic' Leonora Nattrass DIVIDED BY WAR. UNITED BY A SECRET. Berlin,1938. English spy Harry Taverner and Jewish-American photographer Anna Cantrell spend the night dancing at Berlin's most elegant hotel as the Nazi shadow rises over Europe. Neither expects they will ever meet again. But once peace is declared, they reunite in the ruins of Berlin, where Anna is searching for her missing children. With the blockade tightening and the Soviets set on conquest, Harry and Anna walk a treacherous line between love and duty, loyalty and betrayal. And as the Cold War dawns, they are bound together by a secret that will only be revealed decades later, when Berlin finds itself on the cusp of another transformation... READERS LOVE BERLIN DUET 'One of the best and most moving books I have read for a long time' ***** 'A genuine twist at the end' ***** 'Brilliant in every conceivable way' ***** 'This one is something special' ***** 'Beautiful and heart-wrenching - a must-read' *****

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 610

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Praise for

S. W. PERRY

‘Rich, intelligent and dark in equal measure, leaving you wrung out with terror. Historical fiction at its most sumptuous’

RORY CLEMENTS

‘S. W. Perry is one of the best’

THE TIMES

‘Wonderful! Beautiful writing’

GILES KRISTIAN

‘A rattling good read’

WILLIAM RYAN

‘Dramatic and colourful’

SUNDAY TIMES

‘No one is better than S. W. Perry at leading us through the squalid streets of London in the sixteenth century’

ANDREW SWANSTON

‘The writing is of such a quality, the characters so engaging and the setting so persuasive… S. W. Perry’s ingeniously plotted novels have become my favourite historical crime series’

S. G. MACLEAN

‘A compassionate story, skilfully told’

DAILY EXPRESS

Also by S. W. Perry

The Jackdaw series

The Angel’s Mark

The Serpent’s Mark

The Saracen’s Mark

The Heretic’s Mark

The Rebel’s Mark

The Sinner’s Mark

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2024 by

Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

This paperback edition published in 2025 by corvus

Copyright © S. W. Perry 2024

The moral right of S. W. Perry to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

E-book ISBN: 978 1 80546 062 6

Printed in Great Britain.

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For Jane

PART ONE

Running out of time

One

11 November 1942 Languedoc-Roussillon, Vichy France

Dismounting half a mile short of the rendezvous, Harry Taverner began to wheel his bicycle up the track that led into the hills above the village. The late autumn sky was bright and clear and as the path steepened, the view offered itself to him. Ahead, the Corbières rose in folds of arid scrub, dotted with olive trees and rocky defiles. To his right was the sea, flecked with white foam; at his back, the snow-capped Pyrénées. An almost perfect world, he thought. Certainly too perfect to be at war.

To ease the climb and to calm his nerves he sang the jaunty ‘Paris Sera Toujours Paris’ that had been popular before the city fell. And because there was no one to hear him, he sang the lyrics softly but in English – his own little act of defiance against an imagined chorus of marching jackboots. ‘Paris will always be Paris… despite the deep darkness, its brilliance cannot be darkened… Paris will always be Paris!’

His destination was a dilapidated capitelle, a shepherd’s shelter of dry stone with a missing roof. From there you could look down to the village, which lay in a narrow col between this hill and the one to the north, where a ruined castle stood.

Harry had rejected the castle as a rendezvous because it was favoured by courting couples – which he and Anna Cantrell had long ago assured each other they were most definitely not. Not in Paris. Not in Berlin. Not in Vienna. Not now, not ever. The world could wait until it turned to dust and nobody bothered with love any more, because Harry Taverner and Anna Cantrell had a war to win. Besides, the gendarmes in Narbonne were in the habit of raiding the place, searching for contraband wine the village hadn’t already sent to Paris for German consumption.

By the time Harry reached the crest he was sweating heavily inside his coat. He propped the cycle against the crumbling stone wall of the capitelle and glanced at his watch. He was half an hour early.

Dipping into his pannier pack, he retrieved a canvas binocular case and an apple. Squatting down amongst the clumps of wild thyme, he set the apple between his feet. With his hands free he removed the Air Ministry field glasses from their stowage, put them to his eyes and adjusted the focus. Then he began to study the scene in the col below – to pass the time as much as for security – breaking off every now and then for a bite of the apple.

Harry Taverner had taken the coastal road north from Perpignan in slow time because a speeding cyclist drew attention anywhere. Once it wouldn’t have mattered: since the fall of France, two and a half years before, the Germans had left the Zone Libre, the unoccupied sector run by the puppet government in Vichy, pretty much to its own devices. And while the gendarmerie was happy to do the Nazis’ dirty work for them, Harry was confident his name was not to be found on any list in the Gestapo’s headquarters on the Avenue Foch in Paris.

But, three days ago, everything had changed. An Allied army had landed in French North Africa. Now the Germans had responded by invading Vichy France. Since crossing the Spanish border, Harry had passed a steady stream of frightened people heading south. Whenever his gaze met theirs, he saw the same taut expressions, the same anxious eyes he’d seen in 1940 when France had fallen. Some travelled on foot, others in donkey carts, on horseback, or even in motorcars, though God alone knew where they’d found the petrol. He’d seen men in the suits they wore to Sunday Mass, feigning cheerfulness for the sake of nervous wives and children. He’d seen the elderly hiding their fear behind a brittle stoicism, while they wondered if they’d live long enough to see home again.

It must be like this after an earthquake, he thought.

If any of them had wondered why a young man on a bicycle was heading in the opposite direction, they were too preoccupied to call out and enquire. They must surely have recognized him as a foreigner. Tall, long-limbed and with a grace that bordered on the balletic, a loose fringe of flaxen hair habitually falling over the right temple at inappropriate moments but otherwise cut high around the ears and nape, Harry had no need to call out in his well-modulated voice, ‘I say, old chap, what a dreadfully rum do’, to identify his Anglo-Saxon origins. He might as well have carried a tag tied to his lapel that read: If found, please return to the green and pleasant shires of England.

He even had a dimple in the centre of his otherwise strong chin – put there, so his mother told him when he was ten, to remind him that God gives blemishes just as He gives perfections: to see what people’s characters will make of them. At prep school, being by nature a solitary boy with an imagination, he’d told his classmates it was a scar inflicted in Australia by Ned Kelly’s outlaws, who’d shot him with a pearl-handled revolver. They had believed him without question, until the maths master, Mr Foreman, on learning of his preposterous claim, had slippered Harry into confession and repentance. It had been his first lesson in the art of the covert: even a single crack in your cover makes it no cover at all.

Like many an English prep-school teacher of that era, Mr Foreman could have taught the Nazis a thing or two, Harry reckoned with a wry smile. But to give him his due, were it not for his appetite for punishing schoolboy sins, Harry might never have perfected the skill of lying through his teeth while maintaining a straight face.

Take as evidence his presence there today. Although his French was good, it was nowhere near good enough to support the Carte d’Identité de Français he carried. To help him out, the forgers in London had included amongst the thirteen digits on its front cover that recorded his civil status (sex, place and date of birth) two that also identified him as foreign-born. On the inside page, the box recording his place of birth stated Île de Guernesey.

The island of Guernsey – British but occupied – with a centuries-long connection with France, would account for the English-accented French. And if all else failed, as a last resort, he carried in the pack strapped to the pannier of his cycle a rolled-up dark blue blouse. It bore the insignia of an RAF wireless operator/ air-gunner. If the Vichy police caught him and sent him to Paris for the Gestapo to gnaw over, he’d claim to be a downed flier. With a bit of luck, he’d end up in a Stalag.

The alternative didn’t bear thinking about.

In London’s ideal world, Harry would never have been their pick for Anna Cantrell’s case officer. Certainly not as her courier. The Secret Intelligence Service, MI6, would have picked a native-born Frenchman, or a Spaniard antithetical to the fascists. But Anna was his. Anna Cantrell – la photojournaliste Américaine – was his star.

Harry had recruited her in Berlin before the war. Born to an American mother and an English father, her US passport was her protection. It gave her the freedom to live unmolested in Vichy France, because Pétain’s regime had not yet declared war on America. But that protection had vanished two days ago, when the first German Panzer rolled across Vichy’s border.

It was time for Anna to get out. And Harry was on his way to deliver the news in person.

‘What about a radio?’ Anna had once suggested to him over a cognac in an almost empty bar in Port Leucate. Harry had almost had a coronary on the spot. ‘Out of the question!’ he’d told her in a harsh whisper. Wireless sets were as precious as gold dust. Most were earmarked for the networks in the occupied zone. Besides, the Gestapo monitored the ether for suspicious transmissions. And they weren’t listening to Tommy Handley on It’s That Man Again. They could triangulate the approximate location of a sender in minutes.

And so Harry had appointed himself to the post of His Britannic Majesty’s secret ambassador to the court of Queen Anna. With a little help from the British consulate in neutral Spain, and favourable-minded officials of the Spanish Ministry of the Interior, he had rented a house in Portbou on the Spanish side of the border, from which he could make his stately embassies northwards on his black-framed Motobécane, returning with Anna’s secret state papers rolled up in the piston of his bicycle pump.

Observing the village through his binoculars, Harry once again saw how it lay astride a single road that sliced inland from the coast, splitting the terracotta-roofed houses into two opposing ranks that faced each other across the cobbles like Napoleonic regiments awaiting the order to fire their muskets.

At the foot of the village the street parted around a small island where a café stood, and an old plane tree that in summer provided shade for the customers sitting at their tables. Although hidden from him now, Harry knew that beside the café door the Vichy authorities had plastered a poster of a joyful-looking, sun-kissed teenager with a pickaxe over one shoulder: Français! Allez travailler en Allemagne, invited the slogan. Frenchmen! Go to work in Germany. It mentioned nothing about becoming a slave labourer.

His gaze took in the simple stone houses. It lingered on their arched entrances, checking for doors cracked open just enough to give a view of the street. They were all firmly shut. He lifted the binoculars to the shuttered windows behind the little iron balconies on the upper floors. If anyone was peering through the slats, they were invisible to him. Then down again to the main street. No suspicious black Peugeots parked there. No unfamiliar men in overcoats taking far too much trouble over doing nothing. No one sitting outside the café pretending to read yesterday’s Le Matin. Just one old woman in widow’s black, making her arthritic way towards the boulangerie, rolling like a buoy in a high sea as she went.

Despite the stillness the adrenaline went on surging through Harry’s body, making his fingers tingle as he held the binoculars. He’d crossed the border a dozen times this year alone, but the tension now was just as acidic as the very first time. He preferred it that way. Complacency came in only one flavour: fatal.

Moving his gaze to the top of the village, Harry picked out the house Anna rented. It was grander than the others: a neat little villa in the belle époque style – a comfortable bolt-hole for Anna, her two children and her mother, Marion. He imagined Anna in the basement she had converted to a darkroom, bent over her trays of fixer and developer as she brought her pictures to life. He had witnessed for himself her enchantment as the ghostly images emerged from the glistening white paper, speaking to them as if she were bumping into old friends she hadn’t seen for a long time. And she was good, to Harry’s mind, a real artist. She’d told him once that she’d studied under the Austrian art-photographer Rudolf Koppitz in Vienna.

As Harry watched from the hill, the front door of the house opened and into the picture stepped a woman in a dark coat. She turned her back to him and appeared to study the street. Was she, too, confirming the absence of black motor cars and men with unfamiliar faces? As elegantly as a dancer, she turned in his direction and began to walk out of the village, in the direction of the hillside.

Harry leaned into the eyepieces of the binoculars, keeping the woman centred in the field of view, just in case it was not Anna but a lure meant to bring him out of his vantage point and into clear sight of anyone hiding in the old castle across the valley.

At first she was too distant, her movements too often interrupted by the terrain and the intervening houses for him to make out much detail. But he knew it was her, if only by the way she walked: purposefully, a woman with little time for indecision or prevarication. Within moments he could see her face clearly, and then he was grinning widely.

Every time he saw her, he was reminded of Greer Garson: he could make out a pair of finely arched eyebrows drawn slightly together as she faced the wind, the long straight nose, the full but compact mouth. He could see the glint of the sun in the four tortoiseshell buttons set in a square on her wide-collared, blue woollen coat, nipped at the waist. And the trousers she wore instead of stockings, because no one in their right mind would risk valuable silk walking up a dusty, rock-strewn hillside. And the sturdy walking shoes that today hid a pair of delicate ankles. The wind was playing havoc with her hair. She wore it pulled back from the hairline, curled around the ears and curtained across the nape of her neck. But even the Tramontane wind and the effort of toiling up the slope between the clumps of thyme couldn’t diminish her elegance.

You’re still safe, he heard himself say. You’re still mine – even though we both pretend there’s a border between us to be patrolled, protected and defended. Maybe when peace comes we can lift the barriers. We can stop pretending we inhabit different lands.

Rising from his hiding place, Harry waited for her to approach, the binoculars trailing from his left hand.

When she saw him, she called out in that soft American accent: ‘Well, upon my soul, if it isn’t the wandering knight. How’s the quest going? Look, you’ve even brought your trusty steed.’ She nodded towards his bicycle while she set down the photographer’s bag that she carried over one shoulder, her excuse to the village for their secret rendezvous in the hills.

‘There’s quite a Tramontane blowing today,’ Harry said.

It was their all-clear sign. On meeting, he would mention the state of the wind. She would answer, ‘Nothing in comparison to last week.’ Then he would know she was not compromised – no policemen or Gestapo hiding behind the curtains of the rented house. If he didn’t mention the wind at all, Anna would know that it was he who had been compromised. The only drawback was her mischievous habit of teasing him mercilessly. It was a trait she’d inherited from Marion. Her mother was a woman who had yet to meet an authority she wouldn’t attempt to defy.

‘You’re telling me, honey,’ Anna said, leaning close and giving him a kiss on the left cheek that lasted a fraction too long to be considered entirely chaste. ‘I swear the dust has scoured away most of my lipstick.’

Harry rolled his eyes to heaven. He repeated the sentence, this time with more deliberation in his voice. ‘There’s… quite… a… Tramontane… blowing today.’

‘Whatever you say, Harry,’ she replied, grinning at his barely concealed exasperation. ‘The wind’s nothing in comparison to last week. Happy now?’

‘There is a point to all this, Anna,’ he said. ‘I have to know you’re not under duress.’

She laughed brightly. ‘Harry, try spending just about forever in this wilderness with a seven-year-old, a five-year-old and an addled mother. Then you’ll know what duress is. The whole place has gone downhill. The bread that used to be so scrummy now tastes like compounded dust mixed with birdseed. What little meat the charcutier in Leucate sells is mostly all fat. And all the decent wine has gone to Paris for the Nazis to drink. Apart from that, everything’s just hunky-dory.’

‘How’s Marion coping?’

‘Well, the good news is that my mother has discovered it’s about as hard to find cocaine around here as everything else. If there was turkey, it would be cold. So that’s a blessing.’

‘I’m relieved to hear it.’

‘Next time, though, I could do with more warning. What’s up?’

‘That’s the whole point of me coming, Anna. There can’t be a next time.’

She placed one palm against her breast and tilted her head to the heavens, adopting the exaggerated pose of an abandoned woman in a silent movie, while she mouthed, ‘Oh, don’t say it! Abandoned and alone! What to do?’

‘It’s no laughing matter,’ Harry said, confirming it by refusing to smile. ‘Have you heard the news of the landings in Algeria and Morocco?’

Suddenly serious, Anna nodded. ‘Monsieur Bechard told me. He listens to Radio Londres. He said he heard about it on Les Français parlent aux Français.’

‘Well, it’s true.’

‘Madame Soulier says they’ll be pushed back into the sea within a week. But I think she got that from Radio Vichy.’

‘She’s wrong. They won’t.’

‘If you’ve come all this way to warn me the Germans have responded by invading Vichy, you’ve wasted your shoe leather. It’s all round the village. Besides, I didn’t think the traffic on the coast road was for market day in Perpignan.’

‘Then you know you must leave. It’s too risky for you to stay here now.’

‘Leave? Are you crazy – with two children and a recovering addict in tow?’

Harry knew how stubborn she could be – Marion’s influence again. It scared him. ‘Anna, be reasonable,’ he urged. ‘Everything’s changed. You’re in grave danger.’

She shrugged. ‘So what? I’ve been in danger before. Vienna… Berlin… Paris… this girl should have her own page in the Baedeker Guide to Danger.’

It was true, and he had always admired her courage. But this was different. ‘The Germans could be here before nightfall,’ he said. ‘What if your husband comes looking for you?’

That knocked the confidence out of her. He could tell by the way her eyes narrowed.

‘Ivo? Why would Ivo come here?’ she asked, her voice taut.

‘For the children.’

She stared at Harry, then shook her head in a sudden display of anger. ‘No!’

‘Can you be sure?’

‘Sure enough. He’s in some smart office in Berlin, strutting around in his uniform, quaffing Riesling and sucking up to Joseph Goebbels.’

‘But he has friends. He could find out where you are.’

Anna gave a dismissive toss of her head. The wind caught her hair, blowing it across her face. She pushed it out of her eyes with one gloved hand. ‘I have my US passport back now. Marion has hers. We’ll be fine.’

‘It doesn’t work like that,’ Harry said brutally. ‘Vichy might not have declared war on America, but Hitler has. The Germans will put you all in an internment camp. I can’t let that happen.’

She gave him a cold look. ‘What do you mean can’t?’

‘I have the network to think about. You know exactly what you signed up for, Anna.’

There was silence while she considered the implication of what he’d said, silence save for the moaning of the wind. Then, ‘You don’t get to tell me where I go, Harry Taverner. You’re not my husband. And even if you were, I still wouldn’t listen to you.’

Harry counted off a beat or two, allowing her anger to lose itself in the emptiness of the hillside. ‘Even if you’re not afraid for yourself, think of the consequences if you stay,’ he said. ‘You’ll put everyone in danger, every courier we’ve recruited, everyone who’s sheltered an airman for so much as a night while we sent them down the line. You know what the Boche will do to them if they break you.’

Anna sighed. ‘Okay. Okay. You know us Cantrells. No time for borders. We cross every last one we can find, if only for the excitement of what we’ll discover on the other side. How do we get across this one?’

Harry glanced at the pannier bag on his bike. ‘Emergency visas to allow you to enter Spain, arranged through the US consulate in Madrid. I’ve had them for a while. Just in case we ever needed to get you out in a hurry.’

Anna raised her hands in surrender. ‘What do you do for an encore, Harry Taverner – pull rabbits out of a top hat?’

‘Something like that.’

‘Are they real, these visas?’

‘As real as they need to be.’

‘And where would we go, once we’re in Spain?’

‘That’s your decision. America, if you want. Or England. The BOAC service between Lisbon and Bristol still operates.’

‘You’ve planned it all, haven’t you?’

‘Sorry. It’s my job.’

Anna thought about what he’d said, staring at her feet and the dust devils swirling around her boots. ‘It can’t be Britain. You know Marion hates the English with a passion.’

Harry laughed as he imitated her mother’s nasal way of speaking: a Fifth Avenue drawl with hints of Lower East Side speakeasy and a distant shtetl no living relation of Marion’s had known – contrived originally to infuriate her staid parents. ‘You Englishmen! Good for nothing. You’re all either goddamn nancy boys or communists. Or both. That’s when you’re not screwing over the Irish.’

Anna looked up, trying not to grin. ‘She doesn’t mean you, obviously.’

‘Obviously. Even so, you can’t allow your mother’s loathing for your father to put you and the children in danger. She can stay in Lisbon, paint her pictures and sell them outside the Café Brasileira, for all I care. But you can’t let her keep you all here. Not now.’

‘What if she refuses to go? You know Dr Braudel’s proposed marriage—’

‘To Marion?’

‘Well, it certainly wasn’t to me.’

‘Your mother is Jewish,’ Harry said. ‘And even though your father wasn’t, to my gentile understanding – not to mention the Nazi race laws – that means you are, too.’

Anna looked at him as if he was an idiot, which in her presence he sometimes seriously believed he was.

‘Thanks for reminding me, Harry,’ she said, her face impassive. ‘I really had forgotten.’

He scrabbled for the words to make amends, sensing the spreading blush in his cheeks. ‘Look… what I meant to say was… just because you wrote “Roman Catholic” in the marriage register to please your husband, that’s not going to save you. You know as well as I do what’s been happening: the arrests, the deportations. There’s a transportation camp down the road at Rivesaltes, for heaven’s sake, where they send Jews to Germany and only God knows where.’ He looked at her, hard. ‘If the reports are true, the Nazis have started murdering them in an industrial fashion. And when they get here, an American passport isn’t going to save you, Marion’ – a pause for the coup de grâce – ‘or the children.’

Some people show their fear through anger, others through bluster. Some vent it through laughter, or a flat refusal to even admit the danger. At that moment Anna Cantrell was displaying none of those responses. But Harry knew that she was afraid. And it worried him, because in the six years he’d known her, he had never seen her truly afraid of anything.

After an age she said, ‘When do we go?’

He felt like the worst bastard on earth. ‘Now. It must be now.’

‘Are you shitting me, Harry?’

‘If Spain shuts the border when the Germans arrive, not even your emergency visas will get you through. It would mean a trek across the Pyrénées. It’s November.’

The fight went out of her in a gust of breath. She looked around at the hills, as though to give herself a last memory of them. Then she said in a matter-of-fact voice, ‘I’ll go tell them to pack. How much can we take?’

‘Only what you can carry.’

‘Harry—!’

‘We can take the border crossing at the Col de Belitres. Bär can pedal the bike. Antje’s small, she can sit on the pannier rack. If your mother needs a break from the walking, Bär can dismount. He and I can hold a handlebar each while Marion takes a rest on the saddle. Do you think she’ll manage the steep places?’

‘She’s fifty-three, but she walks in these hills to paint. She’ll make it.’

‘She’ll have to. We can’t allow her to slow us down.’

‘Just when I’ve got her clean,’ Anna said, with a roll of her eyes. ‘If we could find her a line of cocaine, she’d be up the Pico de Aneto like a racer. She’d beat us to Madrid by a week.’

For a moment Harry thought she might be serious. He knew she enjoyed being provocative, forcing the observer to look beyond her surface beauty. Or maybe, like her mother, she just enjoyed shocking people.

‘Are you coming down to the house?’ she asked brightly, squaring her shoulders in acceptance of this new reality. ‘The children are eager to see you, and they’ll take the news better if it comes from you.’

He said he would. And, just when Anna turned to lead the way, she saw them: a pair of black Citroëns crawling like scarabs up the Rue du Pla.

Harry heard her appalled whisper even above the wind. Or had he simply borrowed her voice for the thoughts in his own head?

‘Oh, Jesus! He’s found us.’

Anna wondered if she’d been shot. She couldn’t think why else she would be lying on the hillside, the breath gone from her lungs, a stabbing pain in her chest and dark shapes waving before her eyes. Perhaps Harry had been shot too, because his weight was pressing her down into the dirt. Then she realized that it was his body that had felled her, his arms that were pinning hers, his breath that was loud in her ears. She could smell the coarse Spanish soap he used on his skin, like old motor oil.

‘Christ, Harry! You’re hurting me.’

‘Keep your voice down. This wind will carry sound down into the village.’

‘Okay. Okay. Just get off me.’

Rolling away, Harry raised the binoculars to his eyes.

Freed from the pressure of him, Anna lifted her head. The breath came back into her lungs in a rush, harsh and dry. ‘What can you see?’

‘Vichy police,’ Harry said. ‘They’ve stopped directly outside your house.’

‘It’s him,’ Anna replied, the awful certainty twisting her mouth into a slash. ‘I just know it is.’

‘I can see two other men with them. They’re in German uniform.’ Harry paused. Then: ‘Shit—’

‘Let me see,’ Anna snapped.

In transferring the binoculars Harry must have nudged the focus wheel, because when Anna looked through the eyepieces, she saw nothing but a blur. She was looking at the world through a film of watery soup, struggling to sharpen the image because her hands were shaking. When the image finally snapped into perfect clarity, it took what seemed like an age to drag the house into the centre of the view.

They were Vichy police, just as Harry had said – she could tell by their midnight-blue tunics and their peaked, pillbox hats. One of them was hammering on the front door. Anna had the ludicrous urge to shout out to Bär and Antje inside the house, urge them not be frightened because the gendarmes had only come to check if Mama’s American passport was still valid, or ask her if she knew anything about Monsieur Chastain’s wayward son, Auguste, hording petrol in the castle on the opposite hill. But then, as the door began to open, two more men, this time wearing the grey-green tunics of the German Kriminalpolizei – the Kripo – pushed past to take centre stage.

‘Sweet Christ and all his angels,’ she said, the words torn from her as though someone had ripped a dressing off a still-open wound. ‘I was right: he has found us.’

Anna was halfway to her feet, but Harry had already guessed what she might do and was even faster. Again, she felt him slam into her, knocking her back down – if it hadn’t been for her woollen coat she would have shredded her knees on the track.

As he tried to roll her onto her back she lashed out, raking his face with her nails. We’re making angry love, she thought. We’re admitting everything we’ve denied. We’re trying to kill each other.

It was only when he didn’t flinch that she realized she was still wearing gloves.

‘Do you want to get us both shot?’ he said, his voice an angry growl in her ear.

‘I’m going down there,’ she spat at him. ‘I don’t care what he does to me. It’s the children—’

And that was when he hit her. Not designed to hurt. Not in anger. Just to concentrate her mind. A jab to the solar plexus that even the coat did little to soften. Preventative medicine, because he couldn’t risk the lives of all his other agents for one deranged mother on a mission that could only end in their capture.

The breath went out of her again. Her head swam. When she opened her eyes he was lying beside her, the scent of the crushed thyme beneath her head reminding her of the Schwenkbraten they served in the restaurant around the corner from her old apartment in Berlin – even though her attention was otherwise wholly concentrated on the barrel of the Webley revolver he’d pulled from his pannier and was now pressing into her jaw.

‘You’re not going to shoot me, Harry Taverner,’ she said, fighting for air because her lungs seemed to have forgotten their purpose.

‘I won’t have a choice. There are more lives at stake than just yours.’

‘It’s not in you. You’ve got a conscience.’

‘I’ll find a way to live with it.’

She stared into his face, not wanting to believe what she could see written there. He was so close to her that she could see he had a tiny stye in one eye. But there was a resolution there that frightened her.

For the first time since they’d met, she realized that this otherwise polite, uncomplicated, decent man would kill her if he had to.

They lay together in the shelter of the scrub while Harry observed the scene below through his binoculars.

‘Who’s that with him, the one who looks like a crooked accountant out on bail?’

‘Manis Möller, his old boss from Berlin. Please, Harry. I have to see what happens.’

Reluctantly, he handed her the field glasses.

The door of the neat little villa, where they have all lived since leaving Paris, is still open. First to emerge are the two gendarmes. Then comes Möller, the crooked accountant. Behind him, young Bär – seven years old but showing he is the man of the family because his back is as upright as that of a Prussian guardsman. And trailing Bär, attached to him as if she were his teddy, is little Antje. Their faces almost make Anna choke right there on the hillside.

He’s told them he’s bringing them to me, she thinks. That’s why they don’t resist. He’s promised we’re all going to meet in Narbonne, or Paris, or wherever he’s come from. Everything is going to be just fine and dandy. When Christmas comes, it will be the best we’ve ever known. Ivo has lied to them, just as he always did.

But no sign yet of Marion.

From her vantage point in the hills, Anna feels as if she is watching a silent movie, like the ones her father, Rex, used to shoot in Hollywood, before Marion took her back to Europe. She half expects to hear a piano burst into a suitably dramatic accompanying score.

On the screen, the actors are playing their roles as directed. Anna can almost hear the soft whirring as Rex turns the handle of his hand-cranked camera.

The gendarmes are opening the doors of one of the sedans. Bär and Antje are invited to enter. The car doors close on them. From her director’s chair, Anna can see only the top of Bär’s head as he turns to comfort his sister.

The villain of the show, the star everyone has come to watch, is matinée-idol-smart in his Kripo uniform. Tall, blond, chiselled, he pauses before entering his limousine. Then, as if he’s remembered he still has some autographs to sign, he turns on his heel and marches back into the house. And because this is a silent movie the gunshot must be imagined, though Anna is sure a faint clack reaches her after its heroic struggle against the wind. A moment later, the star emerges, smoothly holsters his pistol, joins the crooked accountant in the lead car, and, with exquisite symmetry, the two vehicles execute identical three-point turns, and depart.

Cut! shouts the director. That was fabulous, everyone. Especially Marion. A perfect performance. Oscar-winning, without a doubt.

Marion?

Marion?

Can somebody please check on Marion? She seems not to be moving.

Two

9 November 1989, 8 p.m. Berlin. The Western Sector

On the night the Berlin Wall came down Harry Taverner was standing before the Brandenburg Gate, his polished ox-blood brogues gleaming in the glare of the sodium streetlamps and the TV spotlights, his undiminished hair as white as any concert maestro’s. He cut a smart, regimental figure, his back straight despite his years, his shoulders braced as though he’d forgotten to take the coat-hanger out of his recently dry-cleaned green Loden overcoat.

Around him, free Berlin was transforming herself from a sober European capital into a veritable carnival. At the checkpoints along the concrete curtain that divided the city, thousands of West Berliners were gathering in the chill November night air to welcome the Ossis – the East Berliners – across when, as was imminently expected, the Central Committee on the other side threw in the towel and ordered the barriers raised.

But Harry Taverner did not share their joy that night: he was in the grip of troubled memories, a confusion he could only describe as a sudden attack of temporal vertigo. It was as if time itself was sliding any which way but forward, twisting, coiling into an impossible knot, making him think that he was living in the wrong city, in the wrong year, perhaps even in the wrong life.

And he was late.

Needing an anchor to stop himself drifting, he read for perhaps the twentieth time since he had left his apartment the message written on a small rectangle of battered pasteboard. He held it between the fingers of his leather officer’s gloves, turning it over and scrutinizing it yet again before returning the card to his coat pocket. Then he began to push his way through the crowd, back and forth along this section of the Wall, his mind becoming ever more perturbed.

Occasionally he glanced up at the East German border guards standing atop the parapet. They had been his enemy, once. Tonight, they were observing the growing crowd of happy people below with self-conscious discomfort, their power leaching away with each friendly wave from the West. Leather-coated Stasi policemen with notebooks edged amongst them. Harry supposed they were there to pass on the Politburo’s latest contradictory orders, or just to take down the names of the guards whose officially stern faces were in danger of committing the decadent Western sin of grinning.

Being this close to the Wall and its vivid, invasive weeds of graffiti meant Harry had lost sight of the Brandenburg Gate. This only added to his growing agitation. Pushing his way back through the throng, he found a suitable spot that allowed him a glimpse of the monumental stone pillars topped by the goddess Victoria in her chariot. She was an old friend to him. He had seen her noble and imposing. He had seen her blackened and defeated. He had stood in her shadow and, quite unwittingly, let Anna Cantrell run rings around his professional skill.

The night was cold, but in Berlin Harry had known far colder ones. He recalled the winter of ’46, when fifty-three refugees arriving from Poland had died of hypothermia on the train that was supposed to be carrying them to a new life in the city. Anna had been away in Frankfurt then; he’d been trying to forget her. But that night he’d had a dream in which he saw her face, whitened with frost, and he’d woken in a terror, convinced she’d been on that train.

Time looped another of its coils around him, pulling him even further back, just as his mind had been doing from the moment he’d picked up that little scrap of pasteboard in his apartment, less than an hour ago.

He saw himself standing before his tutor at Oxford, on his way to a double first in History. He smelled burned tobacco in the bowl of a pipe, and old tweed cloth. The day’s edition of the Daily Express lay nearby on an occasional table, pinned down by a half-full sherry glass in case it made a bid for freedom. If he tilted his head a little, he could make out the date on the masthead: Monday, 6 August 1934.

THE HORROR OF THE UKRAINE screamed the banner headline, lest the stark pictures taken by a tourist had somehow failed to tell the full story. STARVED MEN AND HORSES DEAD ON THE ROADSIDE – LEFT FOODLESS BY MOSCOW’S SWOOP ON CROPS.

‘Am I right in thinking your people were refugees, young Taverner?’ his tutor is asking in the refined nasal tones of the English academic.

‘Actually, my father is in shipping insurance, sir.’

‘No, I mean your old people.’

‘Oh, French Huguenots. Came over in the early sixteen hundreds, or so we’re led to believe.’

‘And it’s reached my ears you’ve been spending rather a lot of time in the Ashmolean. An interest in German art, I hear.’

Harry nods. ‘But to be honest, sir, I’m having a little difficulty squaring my admiration for Dürer and the younger Holbein with the present rise of Herr Hitler.’

‘You’re not the only one, Mr Taverner,’ his tutor replies, striking a match and holding the flame to the bowl of his pipe. Then, as if Dürer and Holbein had somehow made a personal recommendation, he says casually, ‘Perhaps you might care to meet some friends of mine in London. Government friends. Nothing too formal. Just a friendly chat.’

And now the memories began to spill into Harry’s head in a torrent: jumbled, competing, utterly disconcerting and discordant – like one of those dreadful avant-garde compositions he liked to call ‘squeaky door music’. He could no longer tell the difference between the past and the present.

‘I have to get across,’ he muttered in German to no one in particular when the frustration became too great to bear. ‘I’ll be late. I can’t be late.’

Feeling a tug at his sleeve, he turned his head. A girl in a white sweater was standing at his side. She looked worried, and it took him a moment to realize her concern was for him. She was much younger than his daughter, Elly – hardly out of her teens – but her eyes had Elly’s compassion for helpless cases. Taking a deep drag on her cigarette, she exhaled the smoke over his shoulder. ‘Are you okay?’ she asked. ‘You look lost.’

‘I should be at the Hotel Adlon,’ Harry told her with relief, as if he’d found amongst the babel someone who spoke a language he could understand. ‘I must be at the Adlon.’

The girl laughed brightly. ‘The Adlon? That was on the other side, wasn’t it? Didn’t they pull it down a few years ago?’

By way of compensation, she offered him the glowing stub of her cigarette.

Harry refused with a confused shake of his head. He hadn’t smoked for years. Or had he only now made himself a promise to quit? He could no longer be sure. He checked his watch. He was running out of time. Or was he running out of lives?

‘I have to get across,’ he said plaintively.

From close by, a male voice called out, ‘Don’t be daft. There hasn’t been a crossing point here since the Ossis shut it in the sixties.’

Looking for the voice, Harry saw an officer of the Schutzpolizei watching him. Desperate now, he reached into his coat pocket and drew out the pasteboard card again. He handed it to the policeman as if it were his identity card, which, in a way, it was.

The officer took it from him and by the light from his torch read the lines of copperplate script. Then he shone the beam into Harry Taverner’s face.

Harry didn’t shield his eyes. He just stood there, as if waiting for the firing squad. As if he knew time had run out.

The officer was a kind man. He had a grandfather in an old-folks home in Hamburg, a survivor of Stalingrad. He knew the signs: he could spot an old warrior in distress where others might not. He lowered the beam of the torch.

‘Is this you?’ he asked, ‘You’re Captain Taverner?’

‘Well, yes,’ Harry said. ‘That was me, once. Now I’m just the old fellow who sits each morning at his regular seat at the Café Kranzler, eating their excellent Bauernomelett and reading his Die Welt.’

As if to be quite sure this elderly, seemingly harmless gentleman wasn’t playing a prank on him, the officer read the words on the card again. And as he did so, he began to understand that this little card was of immense value to its owner, and that he should hold it with great care, because he was glimpsing in the faded print the tiniest sliver of an entire lifetime.

THE HOTEL ADLON IS PLEASED TO WELCOME

Captain H Taverner

TABLE 12, 21.00 HRS

Dress: white tie

Dancing to the music of the Joe Bund Orchestra

9th November 1938

And underneath, written in a hand which – had the policeman been a richer, more travelled man – he might have guessed was that of a maître d’hôtel now long dead, was the addendum:

And guest.

*

The bedside phone rang with a trill that Elly Taverner didn’t recognize. She groped in the darkness, momentarily unsure of where she was. Then her fingers touched cold plastic. Lifting the handset to her ear, her wrist brushed against the small bottle of mineral water she’d taken from the minibar – hotel air conditioning always made her thirsty. She heard it hit the floor and roll under the bed. Had she screwed the top tight before turning out the light? Or was the liquid now soaking the hotel room’s gaudy carpet?

‘Bugger!’ she muttered.

The amber digits on the electric alarm clock told her she’d only been asleep for twenty minutes. It was one in the morning. She felt like shit.

‘Elly? Elly, is that you?’ said a male voice she instantly recognized from the British embassy in Bonn.

‘Sorry, Mike. I wasn’t calling you a bugger.’ She held the phone at arm’s length for a moment while she stifled a yawn. ‘If you’ve rung to tell me they’ve opened the crossing points, you’ve wasted the Foreign Office’s money. I was with the Bundesministerium till gone midnight. It’s like Cup Final day here.’

‘I’m not calling about that, Elly. It’s about your father.’

Elly came out of sleep’s last grasp as if she’d been slapped. ‘Oh, God! What’s happened?’

‘He’s alright,’ Mike’s voice assured her. ‘Seems he’s had a bit of a wobble.’

‘Not another one,’ Elly lamented to the darkened hotel room as much as to Mike. ‘Where is he?’

‘Safe back in his apartment, apparently.’

‘Are you sure he’s alright? Honestly?’

‘I’m told he’s fine, but he got himself into a spot of bother at the Brandenburg Gate. The Schupo took him for his own safety. They checked him out with the Foreign Ministry. Turns out he’s still on their computer, so they called the embassy.’

‘What sort of bother are we talking about?’

‘Nothing serious. He wasn’t dancing naked down the Ku’damm or anything like that.’

I should have stayed at his place, Elly scolded herself. I should have been a dutiful daughter and told Admin to go to hell when they announced they’d found me a bed in a cheap cathouse because Berlin is suddenly home to every journalist in the world. But what thirty-eight-year-old woman wants to doss down in her elderly father’s apartment when the action is all down at Checkpoint Charlie?

‘I’ll go straight over,’ she told Mike.

‘My mum was like that at the end,’ Mike said. ‘Three a.m. phone calls wanting to know why I wasn’t there to take her to the Co-op.’

Even down the scratchy line Elly could hear him gulp at his own crassness.

‘Shit! I’m really sorry, Elly. I didn’t mean—’

‘Forget it, Mike. I know what you mean. Thanks for letting me know. If they call back, I’m on my way.’

Replacing the receiver, Elly Taverner threw back the cheap nylon sheet. Swinging her legs over the side of the bed, her toes landed squarely in a wet patch from the spilled water. She groaned, anticipating the snotty letter to the embassy complaining about how its staff treat their host nation’s hotel rooms like rock guitarists on tour. She fumbled for the wall switch. The light came on like an explosion, as bright as the arc lamps the television crews were using down by the Wall. Half-blinded, she went to the bathroom to fix her make-up; the last thing she wanted was to give Harry a heart attack on top of what she called his RLDs – his recent little difficulties.

In reception, the Turkish night manager was asleep behind his Formica counter. Leaning over, Elly filched a sheet of hotel notepaper. With one of the three pens she carried in her bag on the presumption that a British, B3-grade third secretary, cultural, should never be without the means of taking down her ambassador’s every bon mot for future reference, she left a note for her colleague in room five: Sorry, Derek. Dad’s had a turn. Might miss breakfast. Then she went out through the rear entrance into the car park.

As Elly drove across the city the streetlights and the bright shop windows bloomed in the wing mirrors of the embassy motor pool Opel. But even tuning the radio to the late-night music show on RIAS 2 couldn’t soothe the dread mounting in her. What if Mike had been downplaying things? What if it was really bad this time? She forced herself to concentrate on her driving.

Elly felt more than just a daughter’s concern for a father’s health. There was a professional bond between them too. Harry had once been what she was now: declared – an intelligence agent of an allied power, disclosed to the West German Foreign Ministry. That was why Harry’s name had still been in the Foreign Ministry files. She wondered if she should call her mother once she’d taken stock of Harry’s condition. Glancing at the dashboard clock, she saw it would be seven in the evening in New York – Mum would be charming a client somewhere. Even in her seventies, her mother was still the driving force behind Galerie Louisa Vogel, the international antiques business she’d built while Elly was still a child. She and Harry were like the proverbial passing ships, though Elly knew the marriage was bombproof. When they met up, they were like twenty-year-olds falling in love all over again, which was sometimes a little more than Elly could comfortably take. She decided to wait until she’d assessed the situation. Do what you’ve been taught to do when facing a crisis, she told herself. Nothing. Sit on your hands for a minute or two. Don’t go off at half-cock.

The apartment block was one of the few old buildings in Berlin the Allies hadn’t flattened. It stood at one end of a cobbled street. At the other, a small but jubilant crowd lined the Wall, lit by the streetlamps as if they were actors on a stage. Standing shoulder to shoulder with the East German guards on the parapet were Ossi civilians, mostly young. If she lifted her gaze to the rounded concrete rim she could imagine they were enjoying a pool party, daring each other to jump in fully clothed. She remembered what Louisa had said in her last call from New York: It’s all over the news here. On every channel. I never thought we’d see the bastard thing come down in your lifetime, darling, let alone mine.

Elly found a parking space. It was residents only and there was an empty Landespolizei vehicle parked two cars down. But she took the space anyway, feeling a slight sense of guilt at the immunity the car’s CD plates gave her. She wondered if the police car was there because of Harry or because of what was happening at the Wall. Locking the Opel, she glanced with loathing at the monstrous barrier at the end of the street. She thought of those who’d tried to cross it and failed, shot down in cold blood by the guards. Tonight was their night, the final vindication of their courage.

Pushing through the tall wooden doors of the apartment block, she decided against the ancient lift waiting on the far side of the courtyard and took the wide stone staircase instead, two steps at a time.

The entrance to Harry’s apartment was ajar. The lights were on inside. Standing in the hall she could hear an old woman’s voice lamenting that the Ossis would eat the West out of house and home by Christmas, now that the Wall was open. Elly guessed it was Frau Hedemann from downstairs, come to lend succour to her favourite Englishman despite the hour. Only Harry had the power to prize Frau Hedemann from her godawful puce sofa and the rented black and white television she’d installed for President Kennedy’s visit in 1963. ‘Why do I need colour,’ she would often say to Elly, ‘when I have such brightness upstairs.’ She was referring, of course, to Harry’s smile.

From the lounge came the muted soundtrack of a TV news commentary. Dropping her raincoat onto the art deco chrome coat stand, Elly took a deep breath and called out, ‘Daddy, it’s me. Is everything alright?’

Of course it isn’t, you stupid girl, she told herself. If it was, you wouldn’t be here at almost two in the morning.

But when she entered the lounge, there was old Harry sitting on his Biedermeier sofa in his best dress shirt and black trousers, as comfortable and content as if he’d just come back from the opera. Frau Hedemann hovered nearby with an empty soup bowl, while a young female Landespolizei officer with her cap under one arm basked in her father’s warming smile.

‘Daddy, what have you been up to?’ Elly asked, kissing him on the forehead as he raised his face to hers. ‘You haven’t been arrested, have you? Mummy is going to have a fit when she finds out.’

‘Hello, Puffin,’ Harry said wearily.

Elly winced. He’d coined the nickname during a family holiday on Anglesey. She’d been six.

‘Fräulein Taverner?’ asked the Landespolizei office. She was barely twenty, with blue eyes and tight pale skin from working too many night shifts.

‘Guilty as charged, Officer,’ Elly said pleasantly.

‘My superiors told me you were on the way. I understand you’re with the British embassy in Bonn,’ the officer said in good English, putting her cap back on for extra authority. ‘May I pass Herr Taverner into your care?’

‘Yes, of course you may. He hasn’t caused a diplomatic incident, has he? I wouldn’t put it past him.’

The officer smiled. ‘We just wanted to ensure Herr Taverner was with someone until you arrived. He’s been telling me what Berlin was like when he first came here, before I was born. Before my parents were born, actually.’

Elly rested one hand on her father’s shoulder. ‘He does that a lot, given half the chance. If he’s bored you silly with his awful anecdotes, I apologize unreservedly on behalf of Her Majesty’s government.’

The young woman laughed as she shook her head. ‘Not at all. We ended up watching the news on the television. And Frau Hedemann makes excellent Buttermilchsuppe.’

Frau Hedemann gave a wan smile, as though she’d been accused of ratting to the authorities.

Buttoning her green jacket, the officer made a short formal bow first to Harry, then to Elly. ‘Charmant,’ she said on her way out. ‘Sehr charmant.’

‘Yes, he can be. Very,’ Elly called after her. ‘By the way, sorry about the parking.’

When Frau Hedemann, too, had left, Elly turned down the volume on the TV and sat beside her father. She took his hand in hers, smoothing the skin as if to make it young again, as if to rub away the invisible poison she knew would take him away from her long before either of them were ready for it.

‘What on earth have you been up to, Daddy?’

‘I’ve been a bit silly, Puffin,’ he said distantly, staring at a small brown card she had just noticed lying on the Bauhaus walnut coffee table that Louisa had bought him as a present for his sixtieth. ‘I thought I had an appointment somewhere, but it turns out I was wrong.’

Elly leaned forward over his left knee and retrieved the card. It looked like something you might find in a museum case. She read the words that the Schupo officer had read several hours earlier at the Brandenburg Gate:

Captain H Taverner… Table 12… Dress: white tie… 9th November 1938.

When she read the date, she put her arms around him. She could barely speak because her throat seemed to have suddenly tied itself into a knot. ‘Oh, Daddy.’

When he looked at her, she could see his eyes – usually so bright and clear – were moist.

‘Face it, Puffin,’ he said, patting her knee. ‘Your father’s losing his marbles.’

‘Don’t be silly. It’s alright to get a little confused sometimes. At the embassy, I’m like that by Thursday lunchtimes, to be honest.’

‘I can imagine. After tonight, it’s going to get worse. In a good way, I hope.’

‘Reunification?’

‘Gorbachev has cut the GDR adrift… Honecker has gone… the Ossis have had enough of the Wall shutting them in… In Poland and Czecho they’re staring down Moscow and not flinching… Who knows what’s going to happen now?’

‘Maybe it’s time to go back home,’ Elly suggested. ‘Make Stoke Gabriel into a proper home for the two of you. God knows, you both deserve it.’

A sudden anger appeared to flare in him, though she knew it was directed at himself, not her. ‘I’ll not force Louisa into being a nursemaid. Besides, this is my home. I’ve survived everything that Hitler, Stalin, Khrushchev and all those other desiccated ghouls could throw my way – not to mention Her Majesty’s Foreign and Commonwealth Office. I won’t leave now.’ He jabbed a finger at the television. ‘Look there. See who’s turning out tonight, on both sides of the Wall? Mostly they’re young. They’ve had a generation and more to cleanse the old poison out of their national blood. They’re the future. They – the whole damned continent – need to know that the nation which helped liberate them – the UK – is ready to stand with them now, to encourage them, to help lead them into whatever comes next.’ He gave Elly an apologetic look. ‘Sorry about the speech, Puffin. But you know what I think of that lot back in Westminster. If Harry Taverner is destined to go ga-ga, he’ll damn well do it where his heart is.’

As Elly returned the card to the table, she noticed the photos in their silver frames standing to attention like guardsmen on the sideboard. Each one was as familiar to her as her own memories: Harry and Mummy at Bayreuth for the Wagner… Mummy at the opening of her very first antiques gallery, proudly pointing at the shop sign that read Galerie Louisa Vogel… Harry and Mummy at the house in Devon, taken the winter the pipes burst and the ceiling of Elly’s bedroom fell in and they’d all had to spend Christmas in a hotel in Totnes. And Harry and Mummy on their wedding day, photographed in the Allied sector of 1950s Berlin; Daddy looking as if he’d just stepped out of the Royal enclosure at Ascot, his beaming face a decade smoother than its forty-one years, Louisa an angel in Dresden lace, thirty-six but looking twenty because of all the bliss bubbling away inside her…

‘Daddy—?’ she said, as the thought struck her.

‘What, Puffin?’

‘You met Mummy during the occupation, didn’t you? This invitation – 1938 is positively eons before that.’

‘I’m tired, darling,’ Harry said, kissing her on the cheek. ‘This turn of mine has knocked me back a little. If you want to stay, the spare room is made up.’ He stood and went out into the hallway to his bedroom.

‘Let me get you a scotch to settle you down,’ Elly called, playing along with his evasion.

‘That would be nice, Puffin.’

Taking a decanter from the drinks cabinet, Elly poured out a good measure of her father’s favourite whisky. She knew there was ice in the fridge. On the TV she saw the boxy Trabant cars streaming through Checkpoint Charlie, the faces inside turning to the waiting cameras with the sort of expressions she imagined released prisoners might wear if they’d served a lengthy sentence for a crime they hadn’t committed. It seemed to her an injustice to switch off the set.

When she took the tumbler to Harry’s door there he was, sitting on the bed, still in his shirt, trousers and socks, his polished dress shoes neatly positioned by the bedside table.

‘Thank you, darling,’ he said, as she handed him the glass. ‘You’re a trouper. Sorry to be such a bother.’