Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Krimi

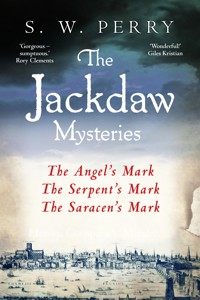

- Serie: The Jackdaw Mysteries

- Sprache: Englisch

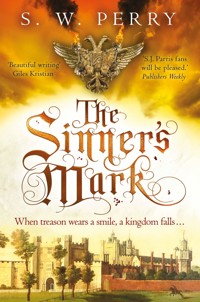

'DRAMATIC AND COLOURFUL' SUNDAY TIMES 'BEAUTIFUL WRITING' GILES KRISTIAN ------------------------------------- Treason, heresy and revolt in Queen Elizabeth's England . . . The year is 1600. With a dying queen on the throne, war raging on the high seas and famine on the rise, England is on the brink of chaos. And in London's dark alleyways, a conspiracy is brewing. In the court's desperate bid to silence it, an innocent man is found guilty - the father of Nicholas Shelby, physician and spy. As Nicholas races against time to save his father, he and his wife Bianca are drawn into the centre of a treacherous plot against the queen. When one of Shakespeare's boy actors goes missing, and Bianca discovers a disturbing painting that could be a clue, she embarks on her own investigation. Meanwhile, as Nicholas comes closer to unveiling the real conspirator, the men who wish to silence him are multiplying. When he stumbles on a plan to overthrow the state and replace it with a terrifying new order, he may be forced to make a decision between his country and his heart... Praise for S W Perry's Jackdaw Mysteries 'S. W. Perry is one of the best' The Times 'No-one is better than S. W. Perry at leading us through the squalid streets of London in the sixteenth century' Andrew Swanston 'Historical fiction at its most sumptuous' Rory Clements READERS ADORE THE SINNER'S MARK 'A thumping good read' ***** 'I was totally captivated' ***** 'Didn't want it to finish' ***** 'Races along at a cracking pace' ***** 'Wow! What a great story' *****

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 608

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Also by S. W. Perry

The Angel’s Mark

The Serpent’s Mark

The Saracen’s Mark

The Heretic’s Mark

The Rebel’s Mark

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2023 by Corvus,an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition published in 2024 by Corvus.

Copyright © S.W. Perry 2023

The moral right of S. W. Perry to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 83895 403 1

E-book ISBN: 978 1 83895 402 4

Printed in Great Britain.

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For Jane, as always.

… And some that smile have in their hearts, I fear, Millions of mischiefs.

OCTAVIUS IN WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE’STHE TRAGEDY OF JULIUS CAESAR

PART 1

Old Friends

1

London, Summer 1600

His plan is to slip into the city unobserved and unremarked. He has chosen the place carefully. The gatehouse guarding the road from the east is bound to be busy at this time of day, a chokepoint for Londoners hurrying home for the shelter of the hencoop before the light fades and the foxes begin to prowl.

A group of gentlemen on horseback, returning from a day’s hawking in the fields beyond St Botolph’s, provides the perfect cover. He falls in between them and a gaggle of servant women bringing in bundles of washing that has dried on the hedgerows in the uncertain June sunshine. A procession of the damned, he thinks, looking up at the raised portcullis hanging above his head like a row of teeth in a dragon’s jaw.

In appearance he is forgettable. The only flesh he carries is in his face, as though God hadn’t allowed enough clay from which to make the rest of him. What remains of his hair is as sparse and wiry as dune grass after a North Sea gale. It is as white as a cold Waddenzee mist. All he possesses are the clothes on his back, the boots that trouble his raw feet, a set of keys, and the ghosts he carries in his pack.

Only in name is he rich.

Petrus Eusebius Schenk.

Petrus after St Peter, long dead. Eusebius in honour of the great Christian theologian from Caesarea, also dead.

And Schenk?

What is there to say about the Schenks? Little enough, other than that they are an honest if unremarkable family from Sulzbach, a one-spire little place astride a crossroads of no note, barely two leagues to the west of Frankfurt.

But this is not Frankfurt. This is London. Aldgate, to be precise, one of the four original towered gatehouses in the ancient wall that the exiled Trojan, Brutus, raised when he founded the city a thousand years ago. A city he named New Troy. Or so it goes.

After all, what are we if not the sum of the myths we tell ourselves?

The short tunnel stinks of horse-dung. From the narrow ledge where the walls reach the domed ceiling an accretion of pigeon-shit hangs like clusters of pale grapes. Slipping out of the crowd as easily as he entered, Schenk drops to his haunches, wincing. It has taken him five days to walk from the place he came ashore – Woodbridge in the county of Suffolk. As he wiggles his feet to ease the cramp in his calves, the sole of his right boot flaps like a wagging tongue. A rivulet of grit trickles down under the instep, adding to the torment. He sits down on the trampled earth and unlaces the boot to inspect the damage. The glue holding the sole in place has split and a few nails have worked loose. It’s nothing a cobbler couldn’t put right in a moment, although Schenk’s coin is all but spent. He won’t receive more until he finds the man he has come to see. Turning side-on to the wall, he hammers the boot against the indifferent stone, silently chanting words from a verse in the Old Testament with each strike: Enticers… to… idolatry… must… be… slain…

Biting against the pain of his blisters, Schenk squeezes his foot back inside the leather and reties the laces. A temporary fix, but it should last until he reaches the Steelyard.

In Schenk’s mind it is always the Stalhof, from the archaic German. His English friends have told him that ‘Steelyard’ is a corruption of an old term for a measuring balance, or a distortion of the name of the ancient fellow who once owned that stretch of land on the north bank of the Thames close to where the Walbrook empties into the river. One thing alone is indisputable: no steel is sold there now, not since the queen’s Privy Council expelled the Hansa merchants from Lübeck, Stade and Cologne.

Schenk knows the story well. For more than three centuries – since the time of England’s third Henry – generations of Hansa merchants have made the little self-contained enclave beside the Thames their home. They have built their houses and their businesses, paid their taxes and worshipped God in their own churches. But they are not wanted in England now. The English can make their own trade in pitch, sailcloth, rope and tar. England has no need of the Hansa merchants any more.

It might be empty, its houses boarded up, but the Steelyard offers Petrus Eusebius Schenk something he craves: undisturbed shelter. Now almost deserted, the warren of warehouses, storage sheds and private homes is the perfect place for a man to hide.

But the echoes of his boot striking the wall have attracted one of the gate-guards, set there to raise and lower the portcullis and to watch for vagrants, papists and other undesirables attempting to enter the city. He walks over. Schenk watches him approach, alarm spiking in his veins.

‘God give you a good evening, friend,’ the man says, smiling without merriment. ‘Do we have a name, perchance?’

A name? Why yes, we have a name fit for a Bohemian prince, thinks Petrus Eusebius Schenk. But these days we must be careful about proclaiming it, in case we linger in the memory of a man such as this. Schenk’s English is good enough to pass muster, though a little too guttural for general taste. As he answers, he prays his accent won’t prick the guard’s suspicion.

‘Shelby,’ he says. ‘My name is Nicholas Shelby, of Bankside.’

William Baronsdale, the queen’s senior physician, breaks his stride halfway down the long, panelled gallery. His gown – a sinister corvine black – flaps around a frame as angular as a sculptor’s armature. The sudden halt releases a faint scent of rosewater from the rushes underfoot, anointed by the grooms to keep the coarser smells from the royal nostrils. In his long professional life, Baronsdale has held every major office the College of Physicians has in its gift to bestow: censor, treasurer, consiliarius, even president. Clad in his formal robe and in the grip of a fearsome indignation, he reminds Nicholas Shelby of nothing so much as a man caught by the sudden urge to burst the swelling head of a particularly uncomfortable boil. Baronsdale’s usually placid Gloucestershire tones tighten in concert with his features.

‘I can remain silent no longer, sirrah. She will die one day. And when she is with God in His Heaven, enjoying the holy balm of His reward, who will abide your heresies then?’

There was a time – and not so long ago, Nicholas recalls – when to give voice to the very thought of Elizabeth’s demise was treason. In the taverns, the dice-dens, the playhouses and the bear-gardens, suggesting that the queen might be anything other than immortal would draw the unwelcome attention of the secret listeners placed there by the Privy Council. But today we need stay silent no longer. Now even the unspeakable may be imagined, made corporeal. Faced. Accepted. Not even those anointed by God can live for ever. At least, not on this earth. Mercy, thinks Nicholas, how times have changed.

Through the open windows the spring sunshine dances an energetic volta on the brown face of the Thames, racing the breeze upriver towards Windsor. The priceless Flemish hangings fidget gently against the wainscoting, caught by the waft from the open windows. And at the end of the corridor: two yeomen ushers in full harness, barring the way. Nicholas can make out the Tudor rose woven in red and white thread into the breasts of each tunic, and in the polished blades of their axes the reflections of himself and Baronsdale, two tiny curvaceous gargoyles with enormous heads. He waits for Baronsdale to resume his march. But Baronsdale seems reluctant to move, glancing at the yeoman ushers to gauge how long he can delay. I understand, thinks Nicholas – there is still a little pus left to squeeze from the boil.

‘I confess it willingly, before my maker,’ Baronsdale announces as if it were a last testament. ‘I have never liked you, Mister Shelby. Never. Your arrogant rejection of the discipline you took an oath to uphold… your contempt for tradition, precedence and custom… Who are you, sirrah, to scoff at the writings of the learned ancients?’

The thin lips fold in on themselves as though sucking water through a reed. The jowls wobble. They have grown pendulous over the years, the only weight Baronsdale carries. They’re where he keeps his store of vitriol, Nicholas decides.

If Baronsdale is expecting an answer, Nicholas is not of a mind to provide one.

‘To my mind, sirrah, you are no better than a mountebank,’ the senior physician continues petulantly. ‘If men of your ilk represent the future of medicine, I see little hope for the continuing survival of Adam’s progeny. I prophesy that within a generation it will be an easier thing in England to find the fabled basilisk than an honest doctor. You could at least have worn your physician’s gown. You look like a… like a…’

Baronsdale has a lexicon that would stretch around Richmond Palace twice over, most of it medical, much of it Latin. But he seems at a loss to find the right words for the hardy-framed man of middling height with the wiry black hair who stands beside him, a look of weary sufferance on his face.

‘An actor from the playhouse?’ Nicholas suggests. ‘A cashiered pistoleer?’

‘Are you mocking me, Shelby?’

‘Not at all. I’m merely repeating what Her Majesty has said to me on more than one occasion. Anyway, I wouldn’t worry. She’s in rude health. She hunts, she dances—’

Yes, and she also ages, Nicholas tells himself. In a few months she’ll be sixty-seven. It could happen at any time. But he’s damned if he’s going to give Baronsdale the slightest satisfaction.

‘If she tires of me, I’ll live with it.’

Baronsdale wags an accusing finger at him. ‘You revel in this, don’t you? Despising your betters, laughing at us, as though you have some superior right to question all we hold to be the truth – a truth revealed to us by the Almighty.’

Nicholas responds with a casual shrug. He’s growing tired of the lecture. ‘I hear you prescribed a freshly killed pigeon to be lain across the ankles of the Countess of Warwick last week, to relieve the swelling,’ he says.

‘Meat that is still warm draws to it the heat of inflammation,’ Baronsdale says defensively. ‘I would have thought you’d have learned that at… Where was it you studied medicine: the butcher’s shambles on Bankside?’

‘Cambridge. And Padua. But the best of it I learned in the Low Countries, on the field of battle. Couldn’t get a pigeon for love nor money: the Spanish had eaten them all.’

Nicholas sets off again towards the yeomen ushers guarding the privy chamber. He wishes to God he hadn’t bumped into Baronsdale in his hurry to answer the summons. He has no stomach for this fight. His wife Bianca, being half Italian, would blaze with anger, were she here. But Nicholas is made of calmer clay. Acting the firebrand will only confirm Baronsdale in his prejudice. And besides, there’s bound to be a prohibition against brawling within the royal verge.

But Baronsdale is right about the queen’s favour. The mercurial nature of her interest in young men with good calves and passable looks is legendary. Soldiers, poets, physicians… if you last long enough to receive a nickname, you’re doing well. As far as Nicholas is aware, he has not yet been honoured with one. He knows that the time will come when her interest in him wanes. The calls to discuss advances in physic and the natural philosophies will become more infrequent. Then they will cease altogether, and Baronsdale – along with all the other elderly worthies of the College of Physicians – will be ready for his revenge. Their spite will be as sharp as any scalpel. They’ll probably drag him before the Censors and have him struck off on some trumped-up accusation that he’s practised witchcraft.

‘I cannot keep Her Majesty waiting,’ he says, laying just enough emphasis on the I to remind Baronsdale that he is not invited. ‘Is there anything you wish me to ask her – while we’re speaking?’

Safely past the first obstacle, Petrus Eusebius Schenk hoists his heavy pack over his shoulder and sets off towards the Aldgate pump. Looking back, he sees the guard trying to settle an altercation between two waggoners over who has right of way through the arch. A cold trickle of sweat makes its way down his spine as he considers how close he had come to disaster.

‘And where are you bound, Master Shelby?’ the guard had asked.

‘The Dutch church at Austin Friars, to give thanks to God for seeing me safely home.’

‘And why would an Englishman named Shelby pray in a church for aliens? Besides, you don’t sound English.’

‘Because I was Dutch before I was English,’ Schenk had explained, struggling to keep his nerve and trusting the man couldn’t tell the difference between a Dutch accent and a Hessian one. ‘I became an Englishman by letters patent from the Privy Council. Cost me more money than I shall likely see again this side of heaven. And I have friends amongst the Calvinist refugee families who live in the Broad Street Ward. It’s good to catch up with old friends after a sermon.’

‘Where have you been, then, to get so dusty and travel-worn?’ the guard had asked, still not entirely convinced.

‘Does it matter?’

‘It might. We’ve been told to keep an eye open for fellows carrying pamphlets.’

‘Pamphlets? What manner of pamphlets?’

The guard had lowered his voice, leaning towards Schenk as though to impart a great secret. ‘Seditious tracts. Puritan tracts. Tracts that denounce the queen’s bishops as corrupters of God’s word.’

‘Mercy,’ Schenk had replied, fearing the guard was about to demand that he open his pack to see if he was carrying such incendiary items. ‘Things have taken a turn for the worse while I’ve been gone.’

And then God had sent a brace of angels to save him – in the shape of two particularly stubborn waggoners, whose irate voices are even now echoing around the interior of the Aldgate arch, to the annoyance of the gate-guard.

Schenk’s thirst is raging now. Once, he would have stopped at the sign of the King’s Head on Fenchurch Street for ale and a bed, but no longer. Too many questioning eyes. Besides, ale is a sinful intoxicant that allows the Devil a way into your soul. Schenk will take honest, God-given water at the Aldgate pump. Then he will walk south along Gracechurch Street towards the river, cut west into Candlewick Street before making his way through the narrow lanes of Dowgate Ward to the Steelyard. How far must he walk before he spots another of his secret companions?

They are always with him. He has seen two on the road from Woodbridge, where he came ashore. The first was a pretty fair-haired youth, the second a woman of around fifty who carried a goose in a wooden cage. He hadn’t spoken to either. He knows it is improper to speak to the dead unless they invite you. Schenk is nothing if not polite, an English habit he is proud to have adopted.

After quenching his thirst at the pump, he encounters the next one between the church of St Gabriel and the junction with Lime Street. She cannot be more than seven years old. She walks with a swaying, merry gait. Her arm is raised so that she may hold the hand of the woman beside her. The child’s dark hair is tucked up in a French coif, a miniature version of the one favoured by the adult – her mother, Schenk assumes.

There was a time when he would have slowed his pace, held back, perhaps even dived down a lane if there was one to hand – anything but face what he knew was about to happen. But no longer. Now he has learned to embrace the inevitable. It is his way of testing himself against the punishment he knows will one day come.

As the woman senses his presence behind her, she turns. Not caring much for what she sees, her grasp on the child’s hand tightens. She steps out across Fenchurch Street, the child stumbling along after her, confused by the sudden change in direction. Just before the woman steers her charge around two apprentice tanners bent under a canopy of hides, the child glances back at him.

Her eyes are exactly what he was expecting: blank, filled with dirt, a worm twining its way out of the corner of one bleached socket. The child smiles up at him, her gums studded not with teeth but with gravel. The tongue lolls – a devil’s tongue, the maggots writhing upwards towards the dark safety of the throat. The dead, Petrus Eusebius Schenk knows, enjoy nothing better than to play their little games with the living.

That was probably me, he thinks.

I did that.

In size, the room Nicholas Shelby is standing in is modest. Barely fifteen paces square, he reckons, with painted panelling and a row of windows looking out over an orchard. Save for a pair of heavy, overly carved sideboards, it is furnished with satin and damask in the style of the Turk, fashionable amongst the quality these days, now that there are exciting new markets in Barbary and the Orient to explore, and an alliance against Spain with the King of Morocco. Instead of chairs or benches to sit upon, a profusion of cushions covers the floor. Nesting amongst them, propped languorously on one elbow, is the majesty of England personified, a potentate in flowing cloth-of-gold, pearls gleaming like the dew on a spider’s web. Her white face tilts thoughtfully towards her breast as one of the ladies grouped around her reads in a soft voice from a leather-bound book.

After what seems like half an hour, but is probably only a minute or two, she looks up.

‘Marry,’ she says, observing the waiting Nicholas and waving away her coterie with the merest spreading of the fingers of her right hand, ‘I see my Heretic has arrived.’

She saw me enter, Nicholas thinks, but I did not exist until she had need of me. In this chamber, time itself is at Elizabeth’s command. She beckons to him to join her. He kneels beside her, a pose he will have to maintain for as long as it pleases her, regardless of the limitations of his commoner’s knees.

‘God give you good morrow, Dr Shelby.’

Nicholas bows his head. ‘Majesty, I came the moment I was summoned. I feared perhaps you might—’

‘Have no concern, sirrah, England is well.’

By ‘England’, she means, of course, herself. And indeed, she looks well enough. But then she always does. The Venetian ceruse is laid on like mortar, the hair as authentic as the mock-Turkish cushions she reclines upon.

‘Then how may I serve, Majesty?’

‘Lady Sarah was reading to me from a new translation of De Rerum Natura. Did you study Lucretius, when you were in… where was it now?’

‘Padua, Majesty.’

‘Yes, Padua. Do you know his work?’

‘I do, Majesty.’

‘And do you believe his claim?’

‘Which claim in particular?’

‘That everything in the world – rocks, trees, animals,’ she gives a regal frown of distaste, ‘ourselves – is in truth made from tiny particles so small that our eyes cannot see them.’

‘I am familiar with the opinion, Your Majesty,’ Nicholas says. ‘Master Shakespeare, in his work The Tragedy of Romeo and Juliet, has one of his players speak of tiny atomi, creatures so small that they can draw Queen Mab’s fairy chariot up men’s noses and into their brains whilst they sleep, to make them dream.’

‘And Master Shakespeare is naught but a saucy rogue,’ the queen tells him firmly. ‘It is a blasphemous suggestion. We are made in God’s image, not Queen Mab’s. Besides, if it were true that we are no more than piles of dust, we would each blow away at the first breeze.’

‘Only a week ago I heard the Bishop of London giving a sermon, Majesty,’ Nicholas says, without adding that he had been forced to attend because the service had been to inaugurate a new president of the College of Physicians. ‘He quoted from Genesis, about us being from dust, and to dust returning.’

‘That’s not the point, Dr Shelby. While I concede Bishop Bancroft may at times be a little dry, I refuse to believe he is made of soil. More to the point, God is most certainly not made of dust and therefore’ – a pause to makes sure there can be no debate – ‘neither is His anointed, the Queen of England.’

‘I’m sure you are right, Majesty,’ Nicholas says. He is accustomed now to the inevitable consequence of these conversations: there is only ever one opinion that prevails.

‘I recall you did us some small service with the Moors a while back,’ Elizabeth says, changing the subject now that victory is hers.

‘That was some seven or so years ago, Majesty – Morocco.’

‘Sir Robert Cecil told me you made a goodly impression on our behalf, with the sultan and his vizier, Master Anoun.’

‘Abd el-Ouahed ben Massaoud ben Muhammed Anoun,’ Nicholas says, giving the man he remembers the courtesy of his full appellation. ‘I believe it is also acceptable to call him by the shorter style: Muhammed al-Annuri.’

Given the Moorish nature of the furnishings, this chamber would well suit al-Annuri well, Nicholas thinks. He can picture the tall, imposing figure lying back on the cushions, his stern features relieved only by the merest twinkle in the hawkish eyes, like the sultan waiting for Scheherazade to tell him another story.

‘You are familiar with Master Anoun?’ the queen asks, as if renaming him by royal decree.

‘I have met him, Your Grace.’

‘You are friends?’

‘I wouldn’t say that. We did each other some useful service.’

At once Nicholas is back standing in the shade of the red walls of Marrakech, parched and dusty after the camel journey from Safi. The sharif’s most trusted minister, he is being told in a reverent tone, as he watches the stately man in the simple white djellaba stalk away. Not that al-Annuri had needed identifying. Nicholas would have known him at once, from the warning he’d received before he’d even set foot on the Barbary shore: Cold bugger… Eyes like a peregrine’s… Not the sort of Moor you’d care to cross… It had never occurred to him at that moment that in a matter of days he would owe al-Annuri his life.

‘Sir Robert told me you wouldn’t be here now, were it not for Master Anoun,’ the queen says, breaking into his thoughts.

‘That is so, Majesty. But nor might he be living in peace and comfort in Marrakech.’

‘So, you understand each other?’

‘Not in our native tongues, Majesty. But we both speak Italian to some degree, though not with the competency I understand Your Majesty possesses. He also has some Spanish.’

Elizabeth eases her position on the cushions. Nicholas thinks he detects the slightest wince of discomfort. He would ask if she was well, but that is not the kind of question a man asks his queen, even if he is one of her physicians. If she is ailing, he will have to wait for her to tell him so.

He remembers the day last year when he caught his one and only sight of the truth behind the royal mask. He had been just behind Robert Devereux, the Earl of Essex, when Devereux had committed the unpardonable insult of throwing open the doors to the queen’s privy chamber at Nonsuch Palace and bursting in upon her. Before the ladies-in-waiting had slammed those doors shut again, Nicholas had caught a glimpse of an elderly woman with taut, pockmarked skin and thinning hair, as unroyal as the humblest Bankside washerwoman. Fortunate, he thinks, that the queen hadn’t caught sight of him, or else he’d probably be under house-arrest like the unhappy earl.

‘Master Anoun is to be received at our court, as the Moroccan king’s ambassador. I want you, Dr Shelby, to be my ears and my eyes in his entourage.’

‘Me, Majesty?’

‘Is there a problem?’

‘No, of course not. When does he arrive?’

‘Not for a while. I am told he is yet to leave the Barbary shore. With fair winds and God’s grace, sometime in August, I would hazard.’

Nicholas mumbles something about how honoured he is to be entrusted with Her Majesty’s commission. In his heart, it is not a task he relishes. Until he had met Muhammed al-Annuri, he had never fully appreciated how much menace one man can exude from beneath an otherwise humble white robe.

‘It will require a display of humility on your part, I think.’

Nicholas eases himself on his haunches. How can Elizabeth be so perceptive when his last encounter with the Moor took place seven years past and more than four hundred leagues away? Then he realizes she is not speaking of al-Annuri at all. She fixes him with a cold gaze.

‘If you are to please us in this matter,’ the queen says, staring at him with a look that is even more unnerving for the false whiteness of her complexion, ‘you must lay aside this petty quarrel you appear to have with Sir Robert Cecil.’

It is raining when Schenk reaches the Steelyard, a sudden hard summer shower. Overhead the clouds are as black as coal, a halo of dying sunlight edging the rooftops and the spires and the darkness of the river where it turns at Westminster. The cobbles shine like polished tin. Now it’s not rainwater but grit that torments Schenk’s right foot; he is walking as though lame.

To his relief, he finds the Lord Mayor’s men failed to put a lock on the Steelyard gate when they expelled the foreign merchants the year before last. The omission saves him having to scale the outer wall that was once the frontier between English London and the mysteries of the foreign Hansa. Pushing through, Schenk heads directly towards his destination. The way is familiar to him. Some of the storehouses and dwellings he passes show signs of recent occupancy. He spots an overturned stool-pot outside one door, a broom propped beside another. One or two have doors forced open, where some of the city’s vagrants have sought shelter, regardless of who once lived here. But most of the properties are just as he expects: dark, empty and abandoned, their occupants banished for ever by royal decree.

On the wharf, wheeling gulls shriek at him, though whether in welcome or in warning he cannot be certain. A skeletal wooden crane still stands forlornly on the quayside, waiting to unload cargoes from the Baltic that will never arrive.

Schenk stops before a modest but neatly timbered house that looks out over the empty wharf and across the water to Bankside. The shadows are lengthening towards night. To his left, stretching across the river like a barrier planted to prevent tomorrow’s dawn from coming too soon, he can make out the mass of buildings on London Bridge and the massive stone piers they stand upon. He has arrived in the nick of time. Any later and there would be no light to see what he was doing.

Dropping his pack, he takes the heavy key from his purse. In the gloom, with the rain now streaming down his face, it takes a while to find the keyhole in the square iron lock-plate. But when he does, the key turns with ease. Count on old Aksel Leezen to oil the lock regularly. Who did he think was likely to come here again when he’d gone? Certainly not the fellow presently standing at his door, one foot tilted to let the rainwater drain out of his boot.

Schenk tugs at the door. But it does not open.

He tries again. The solid Baltic birch planks remain firmly in the frame.

He tries the key again. Once more it turns without resistance. But still the door does not open.

Then Schenk notices a second lock-plate, set a foot or so below the first. He had missed it in the shadows. Someone – either Aksel Leezen himself, or a locksmith sent by the Lord Mayor’s men – has installed another lock. A lock for which he has no key.

Schenk looks up. The little window in the overhanging upper floor is latched shut. Through glass that hasn’t been cleaned in some while, he can make out the interior shutters. He remembers the solid wooden beam that bars them from within – Leezen trusted his fellow merchants even less than he trusted his English customers. It would require a battering ram to break through.

The light is fading fast. Soaked by the shower, Schenk begins to shiver. He fortifies himself by recalling that he has known worse discomforts in his time than a summer shower. Abandoning the house, he searches for an alternative place to hide.

It doesn’t take him long to find one: an empty storehouse near that part of the Steelyard wall that borders All Hallows Lane to the east. Inside, the air is stagnant, oily with the smell of pitch. The barrels themselves have gone, either sold before the enclave closed or stolen afterwards. The place has no windows, but that suits him. If he keeps the door shut, he will be invisible, and invisibility is what Schenk needs as much as he needs food and rest.

He retrieves a tinderbox from his pack and a stub of tallow candle. Its meagre flame shows him a glimpse of brickwork with mould sprouting from the mortar. He makes a slow progress around his new realm, holding the candle before him like a priest’s censer, oblivious to the stink of burning animal fat that make a rancid incense of the smoke. He finds nothing of use; the storehouse has been stripped bare. He will have to look elsewhere, when the rain stops.

The only other illumination is a grey splash of light on the earthen floor. It leads his eyes upwards to a small hole in the roof where a tile or two has blown away. He considers searching some of the other buildings to find enough dry detritus to get a fire going; the hole will make a vent to stop him choking in the smoke. He could do with the warmth, and he doesn’t care to sleep in the dark. That is when his secret companions are more likely to visit him. There are nights when they cluster around him like desperate beggars.

But there are dangers to consider. The Steelyard is not entirely abandoned. Smoke rising from the roof might attract unwelcome attention. When the sun rises, the vagrants sheltering here might come calling. He has nothing of value for them to steal, and though he might once have looked like a diffident chorister, now his plump cheeks have hollowed somewhat, giving him a harder, tougher look. If they are merely curious, he’ll tell them he’s a masterless labourer thrown off the fields for lack of work. Should they come with evil intent, he knows how to use the knife he carries.

Schenk sits down for a while to rest his feet and wait for the rain to ease. He pulls his pack towards him, folding it to his exhausted body as a miser might hug his hoard of gold. From a pouch on the side, he retrieves the remains of the hunk of bread he stole from an unguarded saddle-pack outside an inn at Chelmsford. The bread is coarse-grained and hard, but it goes a little way towards easing his hunger. He begins to plan.

Tomorrow he will go to see the banker. He won’t ask for much. If he has coin, he will be tempted to spend it. Profligacy will only get him noticed. He can wait for his reward. It will be enough just to be dry, less hungry and a few more steps closer to forgiveness.

Returning the last of the bread to the pouch, he starts to unlace the pack’s leather flap. His fingers work cautiously, like those of a man about to open the door upon a scene he dreads but knows he cannot escape witnessing. When the flap is at last free, Petrus Eusebius Schenk draws it back and waits for his secret companions – the little girl with the earthen eyes and the maggots in her mouth… the old woman with the goose in a cage… and all the others – to come crawling out to keep him company.

2

The morning after his audience with the queen, Nicholas makes his way towards the Richmond Palace water-gate, praying with almost every step that he doesn’t bump into William Baronsdale again. His thoughts are anywhere other than on the wherry waiting to return him to Bankside. Thus it is only when he gets close to the jetty that the casual way the oarsmen watch him approach causes a flicker of concern in his mind. Something is not quite right. Nicholas is used to raised eyebrows and doubting looks from the royal servants. Judged against the satins and velvets preferred by other visitors to the queen’s palaces, he knows his plumage is decidedly dowdy – a simple olive-green doublet laced with scarlet points and black Venetian hose, his knee-high boots no better polished than those of the stable-lad at the Tabard inn on Long Southwark. He prefers to leave the collar of his shirt loose, finding a ruff an irritation against his close-cut beard. It’s not that he’s making a point about his humble origins, he doesn’t have the money to dress more fashionably. If he wanted, he could remedy that lack in an instant. His occasional audiences with the queen have enticed a regular stream of courtiers out of the woodwork, most of them presenting with imagined ailments just so that they can dig for titbits of information or use him to curry favour. He refuses to indulge them. Let them whine, he thinks; it’s ordinary Banksiders who have real need of his physic.

But while he might dress like a stable groom, the bargemen at Richmond, Whitehall and Greenwich know him well enough by now. They should be preparing to cast off from the jetty the moment he settles into the cushions, treating him with the urgency their richer passengers expect. Yet they show no signs of alacrity. They sit on their benches as if enjoying a pleasant day out on the river.

Is he to share the ride with someone more important, someone who has yet to arrive? He looks back over his shoulder. Beyond the orchard wall the many towers of Richmond Palace soar into the misty air, each one capped with a burnished dome like an onion stuck atop a painted pole. The multitude of windows gleam like pearls against the red brickwork. It looks to Nicholas as bejewelled as its owner. But the path behind him is empty. He is alone.

‘Are we waiting for someone?’ he asks when he reaches the wherry.

‘Aye, sir. You.’

The lead oarsman doffs his cap.

Nicholas waits for something to happen. But the oarsman does not reach out for the bag that contains his overnight things.

‘I’m ready, if you are,’ he says, beginning to feel a little foolish.

‘A message from Sir Robert, Dr Shelby,’ the oarsman says. ‘We are not to take you to Bankside until you have seen him.’

How petty, thinks Nicholas, to let me find out just as I was about to climb aboard. Could Mr Secretary not have sent word directly to my chamber? Does my refusal to be his intelligencer still rankle?

It will take him a good four hours to walk back to Bankside. He considers going to the stables and asking for a horse. But he suspects Cecil will have sent the groom there, too, with the same message he gave to the wherryman. The only other option is to wait for a public wherry to put in at the Richmond water-stairs. But that might mean a long wait, and the sooner he is back on Bankside with Bianca and little Bruno, the better he will feel.

But the truth is – and Nicholas knows it only too well – to walk, sail or ride is a freedom he does not enjoy. No one in his right mind would so contemptuously disobey a command from the queen’s principal Secretary of State.

Letting out a weary sigh, he turns back towards the palace.

Robert Cecil is standing over a trestle-table in a plain chamber in the Middle Court, the view from the window half-obscured by the pyramid roof of the great kitchen. A chest full of papers lies open beside the table, a small part of the travelling fair of state business that must catch up with Mr Secretary Cecil wherever he happens to be. Watching him from the open doorway, Nicholas imagines he’s looking at a five-foot-tall raven with a pale face and an injured wing, a pint-sized Mephistopheles in a black velvet half-cape tailored to minimise his ill-formed shoulders. He is the bane of Nicholas’s life.

As Nicholas enters, Cecil looks up.

‘What was it this time?’ he asks pleasantly. ‘Lucretius and his nonsense?’

‘She did mention Lucretius, yes.’

Cecil is Nicholas’s age, but he carries himself as if all the wisdom of the ages is contained within his little, damaged frame. It is an intensity that Nicholas always finds unsettling.

‘I haven’t seen you for a while,’ Cecil says.

And that’s the way I like it, thinks Nicholas. He still can’t quite believe that Sir Robert has truly released him from his role as intelligencer. The Crab’s claw is not known for its willingness to let go of anything he might find useful, even if it is in exchange for having Nicholas remain as his family physician. ‘Then let us give thanks that you and young Master William are in good health, Sir Robert. You’ve had no need of me.’

‘I saw Baronsdale a short while ago, though.’

‘I’m sure he sang my praises.’

‘To be honest, he had the look of a whoremaster whose vixens had all decided to run away. Have you upset him?’

‘No more than usual, Sir Robert.’

‘And what of me? How have I offended?’

The question comes as a surprise to Nicholas. Given Cecil’s lofty position, why would he care? It can’t be down to a generosity of spirit; Cecil isn’t that sort of man.

‘I have always been grateful for the favour you have shown me, Sir Robert,’ Nicholas says cautiously. ‘I am happy to tend your boy, should the need arise. Let us both pray that will be seldom, if ever.’

But in the meantime I’d rather you found some other sap to risk his life, and those of his wife and son, in the service of your darker self.

‘Still aggrieved about Ireland?’ Cecil asks smoothly, as though he can read Nicholas’s thoughts.

‘If I’d known you were sending me there merely in order to weaken the Earl of Essex in the eyes of Her Majesty while bolstering your own position, I would have thought twice about going.’

Cecil gives him a cold smile. ‘Still the same plain-speaking yeoman’s son, I see.’

‘I believe it right to be honest in all things, Sir Robert.’

‘Very laudable, if somewhat priggish,’ Cecil observes. ‘Advancement of position without the attendant advancement of manners – that way lies catastrophe, Nicholas. Essex was – still is – a danger to this realm. His ambition will end badly for him.’

‘Robert Devereux’s ambitions were no concern of mine, Sir Robert.’

‘But they are the realm’s concern, Nicholas. That’s why I sent you to Ireland. In these times it is not for a man to decide which duty he will, or will not, honour. When called, he must rise to the moment.’

‘I was called to be a physician, Sir Robert, not an agent of intrigue, politics or deceit.’

‘A physician who cannot afford a new doublet.’

‘I’m a yeoman farmer’s son; we tend to make do with only what we need.’

Nicholas is aware it sounds pompous, but he’s damned if he’s going to let Cecil know that he sends what money he can spare to his father at Barnthorpe. It was only by mortgaging his land that Yeoman Shelby had been able to send Nicholas to study medicine at Cambridge in the first place. With a row of bad harvests giving his parents sleepless nights, a plain doublet is no price to pay at all.

‘If you’re hoping the queen will shower you with riches,’ Cecil says with a wry smile, ‘I can tell you you’ll end up paying far more for the privilege of her occasional interest than you will ever earn from it. My father, Lord Burghley, knew all about that.’

Nicholas considers pointing out that Burghley House and all the other properties the Cecils own didn’t build themselves. But he keeps his peace.

‘I think you should see this,’ Cecil says, taking a sheet of paper from the desk and handing it to Nicholas. ‘It’s an appeal to the queen.’

Nicholas takes the document. The writing is that of someone of modest but thorough education, neat but not flamboyant:

Whereas the Queen’s majesty, tendering the good and welfare of her own natural subjects, greatly distressed in these hard times of dearth, is highly discontented to understand the great number of Negroes and Blackamoors which, as she is informed, are carried into this realm since the troubles between Her Highness and the King of Spain…

Nicholas lets his eyes run on over the list of grievances.

… to the great annoyance of her own liege people that covet the relief which these people consume… most of them are infidels, having no understanding of Christ or His Gospel… the said kind of people shall be with all speed avoided and discharged out of this, Her Majesty’s realm…

‘Unusually for one of these diatribes, this one is actually signed,’ Cecil points out. ‘One Casper van Senden, a merchant, apparently. On the surface, it’s an attack against foreigners, which I consider somewhat rich, given that he’s originally from Lübeck.’

‘And below the surface?’

‘Little more than an attempt to get Her Majesty’s permission to take up those same Blackamoors and transport them out of the realm, for his own profit. The point is, “highly discontented” is a fair assessment of many of those same “natural subjects” he seeks to champion; at least those natural subjects who happen to be members of the city’s worshipful companies.’

‘The guilds?’

‘It was their anger that persuaded the Privy Council and the Lord Mayor to eject the Hansa merchants from the Steelyard.’

‘On what grounds?’

‘They objected to what they believed to be underhand and deceitful foreign practices, undermining the toil of honest Englishmen.’

Cecil tugs at one sleeve of his black velvet gown. Nicholas has seen him do it often, a surreptitious habit to make his crooked shoulders look like those of a better-made man.

‘There is a cold current running beneath the surface of this realm, Nicholas,’ Cecil continues, ‘a current I don’t much care for. People have come to the realization that the queen cannot live for ever. They can smell change coming. And change can be fertile ground for trouble. There are some in this realm looking for an opportunity to make mischief – dangerous mischief. It won’t take much to turn the merely discontented into the violent mob.’

Nicholas recalls what Baronsdale had said to him in the corridor before his audience with the queen: And when she is with God in His Heaven, enjoying the holy balm of His reward, who will abide your heresies then? Perhaps Cecil is conscious that when the queen is no longer alive, he too will have to ride out the rough waters of change, unprotected.

‘This is all very interesting, Sir Robert. But why call for me? I’m no longer your intelligencer. If you want to sniff out mischief, I suggest you buy yourself another scent-hound.’

Cecil seems amused by Nicholas’s show of defiance. He feigns hurt. ‘Mercy, how ungenerous. I summoned you because I thought I could do you a favour, Nicholas.’

‘A favour?’

‘I still hold you in high regard, even if you are somewhat fiery and stubborn. I suppose we must put that down to the influence of your wife’s Italian blood.’

Here it comes, thinks Nicholas: the poisoned chalice. ‘And does that favour require me to travel to, say, Marrakech? Or back to the Irish forests? Will I come away from it thankful to still have my life – if I’m lucky enough to come away from it?’

Cecil smiles. ‘Come now, this is hyperbole. Last time I heard, Suffolk was at peace.’

‘Suffolk?’ Nicholas echoes.

‘Yes, Barnthorpe. That is where Yeoman Shelby farms?’

‘You know it is.’

Cecil gives a little shrug. ‘If you’d prefer not to bother, then so be it. ’Tis no concern of mine.’ He rummages through the papers on the table. Nicholas watches him with mounting unease. Finding what he’s looking for, Cecil lifts another document, this time a small sheet of cheap paper with neatly printed lines of text on it. He waves it leisurely in Nicholas’s direction. ‘I thought you’d be more grateful for the effort I put in,’ he says, in mock disappointment.

‘Effort? Into what?’

‘Why, stopping the magistrates lopping off your father’s right hand for spreading sedition like this, of course.’

3

Even as Nicholas reaches out to take the little sheet of paper, he imagines the axe blade smashing not into his father’s wrist but his own. The physician in him sees in stark but prosaic detail the flesh parting, the tendons severing, the bones splitting. Forcing a professional detachment upon himself, he studies the document.

The first thing that strikes him is the quality of the print. While the paper might be coarse and cheap, the lines of type would pass scrutiny by the Stationers’ Company, whose printers go about their business in the precincts of St Paul’s. The lines are square on the page, regular and clear. But what makes Nicholas’s mouth sag in disbelief are the words themselves. They begin with a rousing call to arms:

A cry to all God-fearing Englishmen…

From there on, the message is uncompromising, chilling in its implacability. It is nothing less than a call to overthrow the very foundations of the queen’s realm:

Away with the vile servile dunghill of those ministers of damnation, the queen’s bishops! Destroy that viperous generation, those scorpions, those puppets of the Antichrist, the murderers of the soul. Let God’s hand strike those who worship false gods, even as they weep pious tears of lying falsity. All will be damned, save those whom God has already chosen. Prayer is not enough; only a pure and sinless heart will speed your reward in heaven. Be our masters ever so mighty, their pride and their vanity will destroy them. Cast them down into the fires of hell where they belong. Let Hooper, the glorious Martyr, be thy touchstone and thy comfort, even when the task seems beyond the strength of thine arm. Deut. XIII.

Be the first to raise thy hand.

‘I presume you studied John Foxe at school in Barnthorpe, if they have such things as schools there?’ Cecil says, reaching out to retrieve the pamphlet. ‘Actes and Monuments?’

Nicholas nods. Being forced to read Foxe’s account of the burning of Protestant martyrs on Queen Mary’s Catholic pyres had kept him awake at night, especially the case of John Hooper. It had taken the pious Hooper almost an hour to die, calling all the while for God to receive his soul, until his jaw burned away. Even then he fought against the torment, flailing his hands against his breast in supplication, until one arm burned clean through at the elbow joint and fell off into the flames.

‘What has this paper got to do with my father?’ Nicholas asks, handing back the tract to Cecil.

‘An identical one was found in his possession.’

‘Found? Where? By whom?’

‘I am not aware of the precise details. All I know is that the magistrates at Ipswich are ready to cut off his hand for disseminating such monstrous sentiments. One is even calling for his execution. Fortunately, when Yeoman Shelby mentioned your name in his defence, they thought it best to consult me first.’

Nicholas stares at Cecil, confused and afraid.

‘Then the magistrates have made a mistake. My father would never be party to something like this. Who arrested him?’

‘Sir Thomas Wragby of Framlingham, Her Majesty’s local justice of the peace.’

‘I know that name,’ Nicholas says, searching his memory. ‘He was a magistrate when I was a boy, then went off to fight with the army of the House of Orange. When I was in Holland, they called him Wrath-of-God Wragby.’

‘You’ve met him then?’

‘No, Sir Robert. By ’87 he was safely tucked away in Delft, on the staff of the late Earl of Leicester.’

‘Well, he returned to England last year, while you were in Ireland.’ Cecil jabs at the document on his desk as if to run it through. ‘And Wragby’s piety seems to have thrived in the damp Dutch soil, because he wasn’t much impressed when your father was brought before him in possession of material like that.’

‘My father isn’t a seditionist, Sir Robert,’ Nicholas insists. ‘He’s a loyal subject of the queen.’

‘Has he never expressed such sentiments to you before?’

‘Of course not! He has enough on his mind trying to make a living from the land he holds. Puppets of the Antichrist? Murderers of the soul? If a bishop dropped by to help my father with the ploughing, he’d be as civil to him as the next man.’

‘This isn’t trivial, Nicholas,’ Cecil cautions. ‘This is extreme Puritanism. You can forget all about observing the Sabbath more properly or eschewing the playhouse and the tavern. You can ignore refusing to wear the white surplice in the pulpit. This’ – another thrust at the tract – ‘this is what the zealots of Puritanism would have come to pass, if they could: the overthrow of bishops and princes. They would have the common people believe that they should have no leader other than God Himself, and that they are the ones who should determine His will on earth. And to promote such nonsense is punishable by death.’

Nicholas tries to imagine his father as a Puritan rebel. He fails utterly. True, he has occasionally heard his father grumble at his lot, but is there a farmer’s son anywhere in England who hasn’t? Besides, Yeoman Shelby has witnessed the realm’s religion change, sometimes violently, from Protestant to Catholic and back again, yet never once has Nicholas heard him criticize the eternal order imposed upon him by God and his sovereign.

‘Did you notice the reference at the end: Deut. followed by the Roman numerals for thirteen?’ Cecil asks, breaking into his thoughts.

‘I assume it refers to the thirteenth chapter in the Book of Deuteronomy.’

‘Correct. And do you happen to know what we would find in Deuteronomy thirteen, were we to look?’

‘I cannot say that I do, Sir Robert. I tended to fall asleep during old Parson Olicott’s sermons.’

Cecil takes a small volume bound in expensive black leather from the desk and hands it to Nicholas. ‘I had to send to Her Majesty’s chaplain for this,’ he says. ‘Finding a copy of the Old Testament, it appears, is like trying to find a physician who gives you a straight answer.’

Nicholas opens the book at the place indicated by a gilded ribbon. Letting his eyes move quickly over the dense print, he soon reads enough to understand why Cecil is worried:

The enticers to idolatry must be slain, seem they never so holy… If thy brother, the son of thy mother, or thine own son, or thy daughter, or the wife, that lieth in thy bosom… entice thee secretly, saying, Let us go and serve other gods… thine hand shall be first upon him to put him to death…

‘Papist credo – that I can deal with,’ Cecil says when Nicholas looks up. ‘But this is something else, something perhaps even more troubling. This is the queen’s own religion distorted into something dark and very dangerous.’

Nicholas points to the single sheet of printed text, the document that could mean his father’s mutilation, or worse. ‘That thing, is it the actual one found in my father’s possession?’

‘Yes. But what troubles me most is that it’s not the only one.’

‘You mean there are others?’

‘We’ve had a few turn up here in the city, in churches mostly. Fortunately they were swiftly handed in. But it’s only a matter of time before news of this... this…’ – Cecil struggles for a word bearing the necessary heft – ‘this plot begins to spread.’

‘I presume you’re searching for the culprit.’

‘Oh, indeed we are. But that’s not as easy as you might think. We’ve been to every printer licensed by the Stationers’ Company, with no luck. Now we must look further afield, for a secret, unlicensed press. There are more than two hundred thousand people in this city. What are the chances of catching the perpetrator with the ink still wet on his fingers?’

Nicholas shakes his head. ‘I don’t understand, Sir Robert. My father would never subscribe to such notions. I cannot believe he would embrace this nonsense, let alone proclaim it in public.’

‘Your father is a lucky man. If the Ipswich magistrates had ignored him when he claimed his son was physician to Her Majesty – something we both know is not strictly true – then Yeoman Shelby could already be missing a hand, at the very least. Earning a living from the soil is hard enough at the best of times, but a missing right hand could be enough to bring the spectre of penury and starvation into view.’

‘Where is he being held?’

‘Framlingham Castle.’

‘If I went there, do you think I could effect his release?’

A rare smile plays at the corner of Robert Cecil’s mouth. ‘Are you asking for my help, Nicholas? I thought you had dispensed with me.’

He’s going to make me beg, Nicholas thinks. He’s going to punish me for daring to break free of him. ‘Only in the matter of acting as one of your intelligencers, Sir Robert. You know of the regard I hold for you in all other matters.’

‘Prettily said. I have already written a letter instructing Yeoman Shelby to be released on your recognizance, pending further investigation. You can carry it to Wragby yourself – take a horse from the stables, if you want; tell the grooms you are about my business. When you get to Framlingham, I recommend you take your father home and talk some sense into him.’

Fumbling his words in reply, Nicholas manages, ‘That’s… that’s… very generous of you, Sir Robert.’

‘I am not one to forget past services, Nicholas. In this uncertain world, you may at least rely on that.’

Perhaps Mr Secretary Cecil’s appetite for duplicity is waning with the passing years, Nicholas thinks. Or is there something else behind this sudden generosity?

‘I’m certain I can resolve this, Sir Robert,’ he says. ‘I know my father had nothing to do with whoever is printing these pamphlets.’

‘I believe you, Nicholas. Caution your father to take more care. And perhaps tell him to avoid the local ale. If, as you say, his behaviour is out of character, they must be brewing some very fiery stuff in Barnthorpe.’

‘He no longer drinks strong ale,’ Nicholas says.

Cecil rolls his eyes. ‘Christ’s wounds! That won’t count in his favour, not if you’re trying to convince Wrath-of-God Wragby that he’s no Puritan. When you see him, I suggest you advise your father to indulge in as many earthly vices as a man of his age may enjoy without injury to his body or his soul.’

Nicholas finds himself replying with an unexpected laugh.

‘If it does not offend, I may disregard that advice, Sir Robert. I think my mother will have had enough shocks already.’

Bianca Merton’s apothecary shop on Dice Lane, between St Saviour’s church and the bear-garden, is doing brisk business. Despite the good weather, Bankside is experiencing one of its frequent outbreaks of troublesome coughs on the lungs. The patent electuary she offers is a mixture of anise, celery seeds and pepper. It is bound in honey, taken from the hives she and her Carib assistant, Cachorra, have recently set up in Bianca’s hidden physic garden down by the river on Black Bull Alley. And Bianca has almost sold out of it. When the door opens for the twentieth time this afternoon, she looks up from her mixing table, prepared to disappoint.

The young fellow making his way towards her seems to be in better health than many in Southwark, and certainly more prosperous. The velveteen shine of his black lawyer’s gown is matched only by the gleam on his plump cheeks and the wide barren stripe that runs between the two halves of his spiky brown hair, like a firebreak between two clumps of gorse. Ducking around the clusters of dried herbs and plants that hang from the ceiling beams and make a heavily scented arbour of the little shop, he stops before her and makes a passable bend of the knee.

‘Mistress Merton?’ he enquires, his eyes uncertain whether to settle on Bianca or Cachorra.

‘This is Mistress Merton,’ Cachorra says, her English tinged with a strong Spanish accent.