Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

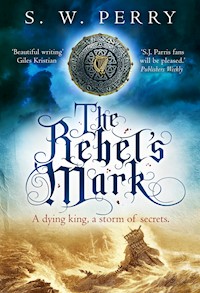

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Krimi

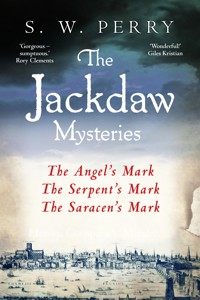

- Serie: The Jackdaw Mysteries

- Sprache: Englisch

'MY FAVOURITE HISTORICAL CRIME SERIES' S. G. MacLEAN 'BEAUTIFUL WRITING' GILES KRISTIAN ----------------------------------- In a world on the brink of change, showing any weakness can be fatal... 1598. Nicholas Shelby, unorthodox physician and reluctant spy for Robert Cecil, has brought his wife Bianca and their child home from exile in Padua. Welcome at court, his star is in the ascendancy. But he has returned to a dangerous world. Two old enemies are approaching their final reckoning. In London, Elizabeth is entering the twilight of her reign. In Madrid, King Philip of Spain is dying. Elizabeth has seen off more than one Spanish attempt at invasion. But still she is not safe. In Ireland, rebellion against her rule is raging. And if Spain can take Ireland, England will be more vulnerable than ever. When Robert Cecil receives a desperate plea for help, he dispatches Nicholas to Ireland to investigate. Soon he and Bianca find themselves caught up not just in bloody rebellion, but in the lethal power-play between Cecil and the one man Elizabeth believes can restore Ireland to her: the unpredictable Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex. Praise for S. W. Perry's Jackdaw Mysteries 'S. W. Perry is one of the best' The Times 'No-one is better than S. W. Perry at leading us through the squalid streets of London in the sixteenth century' Andrew Swanston 'Historical fiction at its most sumptuous' Rory Clements READERS ARE GOING WILD FOR THE REBEL'S MARK 'Exceptional' ***** 'I fall more in love with the characters with each book' ***** 'Brings the past to life' ***** 'Loved every minute' ***** 'Not to be missed' *****

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 679

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Also by S. W. Perry

The Angel’s Mark

The Serpent’s Mark

The Saracen’s Mark

The Heretic’s Mark

Published in hardback in Great Britain in 2022 by Corvus,

an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © S.W. Perry 2022

The moral right of S. W. Perry to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 83895 398 0

E-book ISBN: 978 1 83895 399 7

Printed in Great Britain

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

For Jane.

Into Ireland I go. The Queen hath irrevocably decreed it…

And I am tied in my own reputation.

ROBERT DEVEREUX, EARL OF ESSEX, 1599

I’m off to the wars

For want of peace.

Oh, had I but money,

I’d show more sense.

MIGUEL DE CERVANTES, DON QUIXOTE

PART 1

The Death of Kings

1

The Atlantic Ocean, sixty leagues south-west of Ireland, September 1598

Since the sandglass was last turned, the storm has stalked the San Juan de Berrocal from behind the cover of a darkening sky. It has sniffed at her with its blustery breath, jostled her with watery claws, spat at her with a sudden icy blast of rain. Along the western horizon where the twilight is dying, flashes of lightning now ripple. Whenever the carrack rises on a wave crest, they seem brighter. Nearer. It is only a matter of time, thinks Don Rodriquez Calva de Sagrada, before the accompanying thunder is no longer drowned by the roaring of the sea and the screaming of the wind.

Drowned.

Don Rodriquez has faced death before in the service of Spain. He has made voyages longer and more uncertain even than this one. But to drown… that, he thinks, would be an ignominious death for a courtier of The Most Illustrious Philip, by the Grace of God, King of Spain, Aragon, Valencia, Mallorca, Naples, Sicily and Sardinia.

The deck cants alarmingly as the San Juan plunges down a vertiginous slope of black water. Don Rodriquez flails wildly for something to hang on to. His hands seize the wooden housing of the ship’s lodestar, brightly painted red and gold – the colours of Castile. Beneath his numb fingers, the wet timber is as slippery as if the paint were blood. But to let go, he is sure, would result in him sliding off the deck and into the maelstrom surging mere feet below. He is beginning to wonder if the captain – fearful of interception by one of those sleek English sea-wolves bristling with cannon and possessed of Lucifer’s luck – has made a fatal error of judgement.

As the deck soars upwards again, leaving Don Rodriquez’s stomach somewhere in the depths of the ocean, the captain – a short, taciturn fellow with the darting eyes of a scavenging gull, and whose seaman’s contempt for the landsman who chartered his ship has not abated since they left Coruña – pins his chart against the lid of the lodestar box. The corners thrash wildly in the gale like the wings of a bird trying to escape the hunter’s net. ‘Be not dismayed, my lord!’ he says with an insulting smile as the index finger of his free hand, encased in the thick felt of his glove, makes landfall in the pool of dancing light cast by the helmsman’s lantern. ‘God, in his infinite mercy, has provided us with a safe anchorage – here.’

Don Rodriquez leans forward to study the map. It is a portolan chart, purchased in Seville for more maravedís than he had cared to pay. Everything on it – from the compass bearings to the harbours and inlets, promontories and coves – is based upon reports from Spanish fishermen who once plied these waters. But since the outbreak of the present war between the heretic English and God-fearing Spain there have been few enough of those in these waters. What if the map is out of date, and the English have built a castle where the captain’s finger now rests? Besides, it will be utterly dark soon. Not even a lunatic would consider a night landfall on such a treacherous coast. And only a lunatic who was heartily tired of life would do so in the face of an approaching storm.

‘Here’ turns out to be some distance from Roaringwater Bay, where the captain had promised to put them ashore at first light.

‘Is there nowhere closer? Every extra hour I am ashore is an hour given to the English to contrive our ruin.’

With an impertinence he would never dare risk on dry land, the captain says, ‘We made a pact, my lord, did we not? I am not to ask why a grand courtier of our sovereign majesty wishes to interrupt his voyage to the Spanish Netherlands to spend a night in Ireland. In return, the same grand courtier shall leave all decisions of a maritime nature to me. Yes?’

‘Yes,’ admits Don Rodriquez despondently. ‘We agreed.’

‘Trust me – I know these waters,’ the captain adds. ‘I have sailed them before, with the Duke of Medina Sidonia.’

The man’s familiarity with the coast of Ireland is why Don Rodriquez hired him in the first place. Now, thinking on the fate that befell the commander of the grand Armada, he is beginning to have second thoughts.

Another wave of watery malevolence sends the San Juan into a plunge even more sickening than the last. The sea breaks over the elegantly carved Castilian lion on her prow, and for a moment Don Rodriquez fears she will go on plunging into the deep, never to rise again. From beneath the deck planks, a shrill female scream carries clearly against the clamour of the gale.

‘You had best go below and comfort the noble lady, your daughter, and leave me to my duties, my lord,’ says the captain, fighting the wind for possession of the chart as he tries to tuck it back into his cape.

Don Rodriquez, being a man of honour, objects.

‘You may think me a cosseted courtier, Señor, but I am also a soldier, and I have voyaged in His Majesty’s service before. My arms are still strong. Let me stay here. Direct me as you will.’

The captain glances at his passenger’s well-manicured hands, the fingers laden with bejewelled rings. He looks at the pretentiously styled black curls on his head, the conceit of a man just a little too old to carry them off. A landsman of the worst kind, he decides. A danger on a storm-tossed deck, not only to himself but to all around him.

‘Voyaged where?’ he asks. ‘On the Sanabria, in a pleasure barge?’

‘To New Spain. To Hispaniola.’

The captain looks Don Rodriquez up and down, wondering if this is little more than a courtier’s boasting. ‘You never told me that at Coruña. Was this recently?’

‘Twenty years ago,’ Don Rodriquez admits.

‘Ah,’ the captain says, barely bothering to keep the scorn out of his voice. ‘In that case, your place is not here, my lord. I suggest you go below and leave me and my crew to our profession.’ Then, with the sly smile of a Madrid street-trickster, he adds, ‘I hope you and the women have strong stomachs. We’re in for a tempestuous night.’

Beyond the shuttered windows of the smaller of the two grand banqueting chambers at Greenwich Palace, on the southern bank of the Thames some five miles downriver from London Bridge, the early-September dusk is troubled by no more than a few high wisps of cloud, as insubstantial as an old man’s breath on winter air. Inside, the candles have been lit, the dining boards and trestles cleared away, the covers of Flanders linen folded up and carted off to the wash-house, the plate and silverware removed. As for the diners, if indigestion is in danger of making its presence publicly known, they are doing their level best to suffer in silence. Elizabeth of England does not appreciate having her masques interrupted by vulgar noises off-stage.

Dr Nicholas Shelby and his wife Bianca have removed themselves to the gallery, amongst the other palace chaff who don’t merit a place closer to the players. As a consequence, they have an uninterrupted view of the assembled courtiers bedecked in their late-summer plumage: satin peasecod doublets and venetians for the men, low-cut brocade gowns cascading richly over whalebone farthingales for the women – all striking languid poses around a raised dais covered in plush scarlet velvet. In the centre of the dais stands a gilded wooden chair emblazoned with the English lion and the Welsh dragon. Upon the chair lies a plump cushion covered in the finest cloth of gold. And upon the cushion, like a petite pharaoh perched on a ziggurat, sits a woman with the whitest face Bianca has ever seen.

‘She’s smaller than I expected,’ Bianca whispers into her husband’s ear.

‘Smaller?’ Nicholas answers. ‘What did you expect – an Amazon?’

The court has assembled tonight to enjoy a recital of excerpts from Master Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene, performed by the best actors the Master of the Revels has contrived to drag out of the Southwark taverns and transport – standing fare only – on the ferry from Blackfriars.

On the assumption that mirth at the expense of royalty is probably treasonous, Bianca stifles a giggle. ‘Has she let you see what she hides behind all that white ceruse yet?’

‘Of course not. I’m not allowed to actually touch the sacred personage of the sovereign.’

‘Then how can you treat her if she falls ill?’

‘That’s only half the problem,’ Nicholas replies. ‘What if I have to cast a horoscope before making a diagnosis? If it turns out to be inauspicious and I say so out loud, or write it down, I could be sent to the Tower for imagining her demise. At the moment, that’s treason.’

‘But you don’t believe in casting horoscopes before making a diagnosis, Nicholas. You never have.’

‘But the College of Physicians will insist on it. Otherwise they’ll accuse me of not doing my job properly. Remember what happened to poor old Dr Lopez? Being the queen’s doctor didn’t save him from his enemies.’

‘How can I forget?’ Bianca says, rolling her eyes. ‘I see his head on the parapet of the gatehouse every time I cross London Bridge. It’s been up there since before we went away.’ She pulls a face. ‘Except for the jaw, of course. That must have dropped off and fallen into the river while we were in Padua.’

Nicholas rests his elbows on the balustrade and turns his face very close to hers. ‘If you want the truth, I don’t believe she ordered Sir Robert Cecil to call us back to England because she wanted me to be her physician. She can call on any number of the senior fellows from the College. They’d stab each other with a lancet to get the summons.’

Bianca pushes a rebellious strand of dark hair back under the rim of her lace caul. Holding his gaze, she whispers mischievously, ‘Well, it wasn’t because she was in need of a good dancing partner, was it, Husband?’

Nicholas feigns hurt feelings. ‘It’s not my fault I can’t dance a decent pavane or a volta. My feet spent their formative years wading through good Suffolk clay.’

‘Are you telling me that we subjected ourselves and our infant son to several uncomfortable weeks aboard an English barque all the way from Venice just to satisfy the passing fancy of an old woman who wears whitewash on her skin?’ Bianca asks. Then, as an afterthought, ‘And if that’s her own hair, then I’m Lucrezia Borgia.’

Given his wife’s known skills as an apothecary – and the long line of Italian women on her mother’s side whose art in mixing poisons is still infamous throughout the Veneto – Nicholas winces at her choice of comparison.

‘She likes to hear reports from foreign lands,’ he says, ‘particularly concerning the new sciences. She was very interested to hear about my studies with Professor Fabricius at the Palazzo Bo. She understood everything I told her about the professor’s views on the mechanisms in the human eye.’

‘Mercy! Who could possibly have imagined such a thing: a woman – a queen – understanding the musings of a learned professor?’

Nicholas has learned not to rise to the bait. ‘Besides, I believe she’s grown weary of being nagged by her old physicians,’ he says. ‘It is my diagnosis that she has chosen to discomfort them by favouring someone they all hold to be a dangerous rebel – someone young; someone who still has all his teeth.’

‘You’re her plaything,’ Bianca announces with sly enjoyment. ‘My husband – an old woman’s sugar comfit.’

‘It hasn’t done the noble Earl of Essex any harm, has it?’ Nicholas counters, nodding in the direction of Robert Devereux, lying like a favoured greyhound at the foot of the dais. At thirty-two – four years younger than Nicholas – he makes an elegant sight, only slightly less pearled and bejewelled than the queen herself.

‘No, too thin in the calf for me,’ Bianca says, surreptitiously running the instep of her right foot along the back of Nicholas’s leg. ‘And far too primped.’

On the floor below, two slender youths in gleaming breastplates are striking heroic postures. One declaims as loudly as his adenoidal voice will permit, “Upon a great adventure he was bound, that greatest Gloriana to him gave, that greatest Glorious Queen of Faerie land—”

‘Tell me again, Husband: which one is the Gentle Knight?’

‘Him – the one with the broken nose.’

‘Why does he have that silly painted horse’s head between his legs?’

‘Didn’t you catch the line about his angry steed chiding at the foaming bit?’

‘Foaming bit? It looks to me as though someone’s stuck a giant painted wooden pizzle onto his codpiece. It’s the sort of thing I expect to see on a Bankside May Day, not at Greenwich Palace,’ Bianca says, making a play of fanning the embarrassment from her cheeks.

‘Just try to imagine it’s an angry steed, please.’

‘So, the other one – the one with the superior look on his face – that’s Gloriana.’

‘Correct.’

‘And Gloriana is really Elizabeth.’

‘You have it in one.’

‘And this fairy land they’re in – that’s really England.’

‘It’s an allegory,’ Nicholas says slowly, a hint of weariness in his voice.

‘It’s a delusion, that’s what it is – a woman in her sixties being played by a boy who’s barely plucked his first whisker.’

‘Edmund Spenser is our finest poet,’ Nicholas protests, not altogether convincingly.

‘I’ll take Italian comedy – Arlecchino and Pantalone – over your Master Spenser’s allegory today and every day, thank you, Husband.’

A portly factotum from the Revel’s office, lounging unnoticed against the wainscoting, leans forward. ‘Some people prefer to listen to quality verse,’ he mutters, ‘rather than the bickering of other people who are clearly devoid of any artistic appreciation whatsoever.’

‘Sorry,’ says Nicholas.

‘How long will this go on?’ Bianca whispers.

‘It’s a very long poem.’

‘Do you think anyone will notice if we sit down against the wall and take a nap?’

‘Don’t worry,’ Nicholas tells her. ‘Gloriana herself will have nodded off long before the end.’

‘Then we can all go to bed?’

‘Bed?’

‘That painted pizzle has given me an idea.’

‘The players will all pretend she’s wide awake. So will the court. You can’t escape Edmund Spenser that easily,’ Nicholas says despondently. ‘I fear we’re in for a long night.’

Aboard the San Juan de Berrocal, Don Rodriquez huddles in the tiny cabin afforded by his status as a courtier and longs himself back in the Escorial in Madrid with his dying monarch. Anywhere but here, where the world seems as if it is trying to disassemble itself in a shrieking, plunging, battering paroxysm. Clasped in a terrified trinity with his daughter Constanza and her Carib maid Cachorra – calm, stately, brave Cachorra – his only comfort is that if tonight he must die, he will not die alone.

‘Is it to be thus, Father?’ Constanza asks in a moment when the howling of the wind, the crashing of the sea and the tortured groaning of the vessel subside just long enough for her voice to be heard. ‘Am I not to know the blessings of marriage and motherhood? Am I to perish in the company of common mariners? Is this the pass you have brought me to, my lord Father?’

To the mind of Don Rodriquez, common mariners are all that now stand between his daughter and a watery grave. But Constanza is made in the mould of her late mother, choosy about the company she keeps ever since she was old enough to distinguish one face from another. She is a plump, haughty girl, whose fingernails have been sunk in his skin almost from the moment he entered the cabin to warn her of the approaching storm. He cannot see her face in the darkness, but he knows the look she is wearing well enough: the full lips turned down at the edges; the eternal crease between eyebrows stiffened to the texture of a brush with kohl, charcoal and grease (Constanza cannot come down to breakfast each morning until Cachorra has properly applied it); the air of permanent dissatisfaction, despite never knowing a moment without luxury until she boarded this ship.

At least the storm has taken away her hunger, he thinks. Every day since leaving Coruña she has turned up her nose at the food, utterly unaware that the very mariners she so disdains are on hard rations because half the St Juan’s hold is packed with crates containing her trousseau.

‘God grant His torment will soon be over,’ Don Rodriquez tells her with more certainty than he has any right to feel. ‘And when we are done with Ireland, which will be no more than a day or two, we shall continue on our way to Antwerp and the joyous occasion of your wedding.’

Unobserved in the heaving darkness, he allows himself a shallow smile. A joyous occasion indeed, if only for the fact that Constanza will become someone else’s worry. She is to marry a preposterously mannered cousin, currently in the service of King Philip’s commander in the Spanish Netherlands, Archduke Ernst of Austria. By all accounts they will be well suited. They can look down their noses at the Flemings, the Brabantians and the Dutch to their hearts’ content. He will stay for the ceremony, of course, but not a moment longer. With God’s grace and favour, he will be back at the Escorial in time to mourn his dying king.

Don Rodriquez feels his daughter’s chest heaving against his. He takes this as evidence of her mounting terror. Then the stomach-churning stench of vomit permeates the closed air of the cabin and he senses an uncomfortable warmth spreading into the weave of his expensively brocaded jerkin. God’s punishment, he thinks, for his lack of charity.

From above the deckhead – though at this moment if they were capsized and upside-down Don Rodriquez is certain he would be none the wiser – comes a rapid series of crashes, loud enough to beat down even the frenzied screaming of the wind. He has grown uncomfortably familiar with the booming of the sea hammering against the San Juan’s planks. But these sounds are different. One of the masts must have gone, carrying heavy spars and tangled cordage with it. This is it, then, he thinks: the end. The sacred mission entrusted to him is ruined, stillborn, smothered even before it has left the cradle.

And then Don Rodriquez feels the fingers of another female hand, less frantic than his daughter’s. They are seeking out the profile of his face in the darkness, as though the owner of them is trying to fix a last memory of him in her mind before the sea breaks in. He knows at once they are Cachorra’s fingers. They have a strength in them, a resolve that he knows well, though no physical intimacy has ever existed between himself and his daughter’s Carib maid. Freeing one hand from his daughter’s frantic grasp, Don Rodriquez places it over the other woman’s fingers and presses them against the side of his face. There is no light to see by, because the cabin lantern has long ago spun itself off its hook and now lies shattered somewhere amongst all the other debris that slides around in the darkness. So it is in his imagination that Don Rodriquez looks into Cachorra’s astoundingly large brown eyes – eyes that every Spanish woman who has ever seen them says can only be the result of taking a measure of belladonna, because no one is ever born with eyes like those – and, for the first time since the storm struck, he knows comfort.

At Greenwich Palace the performance of The Faerie Queene is drawing towards its ponderous and impenetrable close. Several of the players, Bianca has noticed, are regulars at the Jackdaw on Bankside. She knows them well. She can see their hearts aren’t in their work. She feels for them. It cannot be rewarding when the one person you have come to entertain has spent most of the evening in conversation with the Earl of Essex and several serious-looking members of the Privy Council, taking little notice of your performance.

Nicholas is almost asleep on his feet. Every few moments his head pitches forward and his close-cut beard rasps on the starched ruff that Rose Monkton insisted on laundering for him. Dear Rose. She still cannot quite comprehend that she is no longer Bianca’s maid but the legal tenant of the Jackdaw, along with her husband, Ned.

It was Ned Monkton who had made it safe for them to return to England. It was Ned who had killed the lie that Nicholas was old Dr Lopez’s co-conspirator in a plot to poison the queen, a slander that had forced Bianca to accompany her husband across the Narrow Sea, eventually seeking refuge in her birthplace, Padua, until his innocence could be proved. That acquittal had taken more than a year. By the time word reached them, Bianca was pregnant with little Bruno. Nicholas, too, was fully occupied studying anatomy under Professor Fabricius at the Palazzo Bo. Returning at once was out of the question. Besides, Robert Cecil valued having proxy eyes and ears in the Veneto and had wanted Nicholas to stay.

Then, last Twelfth Night, one of Cecil’s enciphered messages had arrived at their house. The queen, apparently, had found time to enquire what had happened to that fetching young physician, the one with the tousled black hair and the frame of a ploughman, the Suffolk yeoman’s son with the country burr in his voice, the one guaranteed to discomfort the grey, hidebound ranks of her royal stool-inspectors, urine-watchers and medical astrologers.

There had been no argument from Bianca about leaving. She had no family left in Italy, and before fleeing England with Nicholas had made a good life for herself on Bankside. Her sojourn in Padua, while pleasing enough, had merely reinforced her conviction that England was her home now. Besides, had Nicholas elected to stay in Padua, he would have announced himself a traitor to his sovereign and the country of his birth.

But which one of us is the worm in the apple’s flesh – me or my husband? she asks herself as she watches the players end the performance with a lively jig played on sackbut and tambour. Does Robert Cecil not wonder if Nicholas might have warmed a little to the Catholic heresy while he was away in Italy? All those papist professors at the Palazzo Bo whose intellect Nicholas so admired… all those provocative altar paintings he was exposed to in the churches she took him to, the forbidden Masses he attended…

She can see Cecil now, from her vantage point in the gallery. There he is – almost directly below her – a crooked little thing in a lawyerly black gown, casting furtive daggers from his eyes at the perfection that is Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex.

Cecil has known of Bianca’s heresy long enough. He has always tolerated it because Nicholas is one of his most trusted intelligencers. But how, she wonders as she looks down with the faintest trace of a wry smile, can the queen’s principal secretary be certain that the man who answered his summons is – upon his return – in all regards the same man who left?

2

The dawn has arrived – and, with it, God’s mercy. Like a disappointed matador faced with a cowardly bull, the storm has departed without bothering to stay around for the final, fatal thrust. The black night of terror they have endured was nothing but an auto-da-fé, a test of faith. It is a test Don Rodriquez believes he has passed. His abiding memory of the trial is not the raging of the tempest, the fear, the stench of his daughter’s vomit on his doublet, but of Cachorra’s touch against his cheek.

Beneath the cabin door a pale, narrow blade of grey light sweeps back and forth, as if searching for survivors within. We’re here! he wants to shout at the sliver of probing dawn. We’re alive! Instructing Constanza and Cachorra to offer prayers for their deliverance, he unbolts the door and goes out into morning to assess the damage.

What he sees astounds him. The wave tops are as high as the sides of the ship, rolling the San Juan like dice cupped in the hand of a desperate gambler on a losing streak. As the waves break, sheets of dazzling white foam stream across the deck, borne on the still-wicked wind. As the first low rays of sunlight pierce the fleeing black clouds, he braces himself against a tangled thicket of cordage, the ropes icy wet to his grasp, and shakes his head in wonder.

Only the lower part of the mainmast still stands, the noble Galician pine shredded at the break as if it were nothing but common kindling. The quarterdeck rail on the leeward side has been torn away, the posts – crowned with finely carved Castilian lions’ heads – now so much driftwood lost somewhere in the night behind them. Not a single lantern has survived. Several of the deck cannon have gone, their rope tackles sheared. Many of the others are jumbled and overturned like nursery toys. If the English come across the San Juan now, Don Rodriquez thinks, they would have nothing in their hearts but pity. But not even the English would be so foolish as to venture out in seas like this.

On the main deck the sailors whom the sea has not taken in the night ignore the courtier’s sudden appearance. They are too busy wielding axes and knives, trying to cut away the tangle of ropes that coil across the deck like the snakes on a gorgon’s head. Their bodies seem bound by invisible bands of exhaustion, their movements laboured and dispirited. They remind Don Rodriquez of the native slaves who toil in the gold and silver mines of New Spain, barely human at all.

Turning to look up at the poop-deck, he sees the captain leaning over the side, observing the huge mat of tangled rigging and shattered yards that clings to the San Juan de Berrocal like a beard, rising and falling as the sea breaks against her. Noticing the newcomer on deck, the captain turns his head. Gaunt and red-eyed, he wears the expression of a man who has already stared into the burning eyes of far too many demons to care much about what awaits him in hell.

Don Rodriquez climbs what is left of the ladder to the poop-deck. From here he can see – between the surging wave crests – two small, jagged islands on the horizon. The captain points to a pair of inverted Vs on the portolan chart, about a finger’s width from the Irish coast.

‘We call the larger one Isla Santa,’ he says, his voice a mere croak after a night of bellowing commands against the noise of the storm. ‘There’s a monastery on the peak. In their own language the heathens call it Sceilg Mhichíl. Ireland is but two leagues on. We won’t see it yet, because of the waves.’

‘Perhaps the monks will offer us sanctuary,’ Don Rodriquez says. Even a tiny rock two leagues out into the ocean would be preferable to a minute more of this, he thinks.

‘There are no monks,’ the captain tells him with a disturbingly wild laugh. ‘It’s deserted. And even if there were, we cannot make a safe landfall there.’

‘What hope do we have of reaching Roaringwater Bay?’ Don Rodriquez asks.

The captain stares at him as though he’s speaking Cachorra’s native Carib.

‘I understand you are used to the comforts of court, Señor, and therefore unaccustomed to my firmament,’ he says. ‘But even you must have realized by now that we’re drifting at the mercy of wind and current.’

Señor. Don Rodriquez cannot help but notice this is the first time the master has called him anything less deferential than ‘my lord’.

The captain looks out towards the rolling, pitching horizon. ‘I’ll order the anchors dropped when we reach shallower water,’ he says. ‘You’d best pray to Almighty God they hold.’

‘And if God doesn’t hear me?’

The captain looks at Don Rodriquez with something bordering on contempt.

‘Then pray to the Devil instead. All will depend on where we get blown ashore.’

I’ll order the anchors dropped… You’d best pray to Almighty God they hold.

But the anchors have not held.

Now that the last of the ripped canvas had gone overboard, a fatal lassitude has fallen upon the San Juan. Isla Santa has long since disappeared astern. Now the only sounds to be heard are the funereal drumbeats of the waves pounding against the hull, the keening of the wind and the murmured praying of the crew. Everyone is praying now. Prayers are all they have left.

Don Rodriquez kneels on the quarterdeck and claps his hands together as though making a last confession before going into battle.

‘Holy Father, have mercy on a poor sinner. Make your eyes to shine upon us and your grace to bear us up above these trials… You’ve done it once. You can do it again. Spain needs me…’

He knows the chances are slim. Most of the coastline here is unforgiving rock that towers above the breaking surf. He can see it drawing relentlessly nearer every time a wave crest breaks. It will smash to pieces what is left of the San Juan. Human flesh and bone won’t last a minute. Better to drown than be flayed alive.

But if, by God’s great fortune, they do survive the inevitable wreck, what then? wonders Don Rodriquez. Can a way be found to the meeting place? Will the Englishman wait for him? Can the enterprise upon which he is embarked be rescued, even in the face of disaster? All will depend upon whose hands – besides God’s – are waiting to catch them.

If they find themselves amongst the Irish who have risen in revolt against the heretical English queen, then all will be well. Spain is a long-standing ally of all who would see the Protestant heretics chased out of the island ahead. He will be feted by their chieftains, perhaps even by the rebel leader himself, the Earl of Tyrone. It will take a while, but there is every reason to expect that these good Catholics will help him find another vessel to carry his daughter and Cachorra on to Antwerp, though with the trousseau and the dowry at the bottom of the sea, her exquisitely noble groom might think somewhat less of the match and tear up the contract. So be it. Constanza will sulk for a month or two, but he’s used to that.

But what if there are other hands waiting to catch him? If he falls amongst the English settlers who think they hold this island for their ageing queen, what then?

In that event, Constanza herself will be his cover. A Spanish nobleman and his daughter shipwrecked on a voyage to her marriage is a tale that should play well enough with a nation that loves the frivolity of the playhouse. Constanza will speak for him. She has good English, taught to her by Padre Robert of the Jesuit seminary at Valladolid. It was Robert Persons himself who, on the quay at Coruña the day they departed, had wished them God’s fair winds.

There is bound to be a period of confinement and interrogation in some draughty castle. But why should any minister of the English queen consider his appearance in Ireland to be anything more than what he will say it is: an unfortunate shipwreck on the way to a wedding? The food is likely to be unbearable and the company vulgar. A little of the family plate and jewels back in Castile may have to be sold to raise a ransom. But it has happened before. Who knows, in Antwerp the lucky groom may even wait, poor sap. Yes, Don Rodriquez thinks, if we fall into English hands, Constanza will be the saving of us.

The rocky cliffs are much closer now. The roar of the ocean breaking against them grows louder with every passing moment. The end cannot be long in coming. Don Rodriquez is not afraid. He has faced danger often in the service of Spain. He wonders if the dying King Philip will learn of his fate before his reign ends. A king’s prayers should count for something in the ledger of a man’s life.

Sensing movement at his shoulder, he turns – to find himself staring at a plump Madonna in a green satin gown, a black lace mantilla covering her features. For a moment he is speechless. His exhaustion must be playing tricks on his mind. Then the Madonna speaks, her voice muffled by the folds of the mantilla.

‘If I am to die, Father, I shall die as the bride of José de Vallfogona y Figaro-Madroñera!’

Constanza pulls aside the black lace veil. The full lips that have never quite decided if poise or petulance should be their lodestar are trembling. Her eyes dart from the rocks ahead to her father’s face, accusing both. Behind her, Cachorra gives a resigned shrug, as if to say, She ordered me to dress her. If she wants to drown in her trousseau, who am I to disobey her command?

Before he finds his voice, Don Rodriquez can do little but stare. ‘Christ’s most holy wounds, Daughter! What nonsense is this?’

Constanza begins to wail.

He considers telling his daughter sternly to accept what must be accepted. Face it like a true daughter of Spain. Bear it the way your late mother bore the illness that carried her off. Show the same fortitude as your dying king. But he is not an uncaring father, so he remains silent. He puts an arm around Constanza’s shoulders. Her little button-nose puckers at the smell of the vomit she left on his doublet all those hours ago.

It is Cachorra – the leopard cub that has grown to strength and beauty since that day in Hispaniola when he first set eyes upon her – who now shows more courage than any of them. She stands watching the oncoming cliffs as though they hold not the slightest danger for her. What right did I have to pluck such a flower from the edge of the known world, Don Rodriquez asks himself, only to bring it to a terrible end on a rocky Irish coast?

But it is too late now for remorse. Besides, Holy Spain has plucked whole meadows of such flowers from the golden lands across the ocean. What is one amongst so many?

The San Juan is now almost upon the rocks. Don Rodriquez can see in clear detail a jagged promontory jutting out towards the vessel, the sea breaking over its base in wild detonations of white foam that shine in the morning sunlight like clouds of jewels scattered from a giant’s hand.

As if to a silent command, several of the praying sailors rise from their knees, pointing, laughing, waving. Even cheering.

Now Don Rodriquez can make out, either side of the sharp promontory, the entrances to two sheltered coves, each with a curved strand of shingle at the foot of steep, craggy bluffs. He allows himself a brief feeling of relief. God has not forsaken Spain. God never would.

Facing the shore, he has his back to the wave that comes in from the ocean like a thousand horsemen charging flank-to-flank. It breaks against the windward side of the San Juan in an explosion of white foaming water. She rolls almost onto her beam ends, toppling crew and passengers, scattering them about and mixing them with the debris that the storm has not already washed overboard. Don Rodriquez himself fetches up against a tangle of heavy pulley blocks and cordage, breathless from the impact, the icy brine burning his eyes, soaked and bruised, but still alive.

As though reflected in an imperfect mirror glass, he sees the distorted figure of Constanza some distance away across the deck. She is lying on her back, the expensive gown he bought her for her marriage transformed into a sodden winding sheet, her arms and legs flailing wildly. He can hear her shrieking in protest at this final humiliation. And he sees Cachorra – who has served her mistress with such quiet forbearance since the day the infant Constanza was able to issue her first unreasonable demand – running towards her across what looks to him like a fast-flowing ford, kicking up water as she goes.

It is barely an instant before he sees what Cachorra has seen: Constanza’s left foot has become entangled in some rope netting that is already sliding over the side, dragging his daughter with it.

Exhausted by the storm and the sleepless hours spent in anticipation of his life’s violent end, Don Rodriquez can barely find the strength to climb to his feet, let alone follow Cachorra across the deck. He stumbles after her, his eyes brimming with salt spray. As though viewed from behind a waterfall, he sees Cachorra reach his daughter, squat down and deftly free her from the jumble of cordage.

And then a second wave bursts over the deck.

It spins him around, slamming him up against the wooden bulwark, folding him over the painted rail like someone peering over the parapet of a bridge. He stares down in stunned confusion at the seething holly-green water.

Across his sight – carried on a sudden churn of the current – sweep the upturned faces of Constanza and Cachorra. They stare up at him, as though they have yet to register the shock of being swept overboard.

And then they are gone – lost in the tumbling spume.

Don Rodriquez Calva de Sagrada lifts his head to the sky in anguish, a sky now so clear and blue that it might never have known a single storm since its very creation. A howl of despair escapes from his mouth, heard clearly even against the crash of the waves.

The tossing back of his head takes his gaze up the jagged promontory to the very top of the cliff. He searches for God’s face in the sky, wanting to demand of Him the reason for such arbitrary cruelty. But all he sees is a line of horsemen drawn up along the precipice, looking down at the drama playing out beneath them.

Bianca lets her tired eyes wander around the sparse whitewashed interior of the guest chamber. She had expected that a royal palace might have guaranteed a more comfortable night’s sleep. Beside her in the bed, which no one has thought to hang with curtains, Nicholas is sleeping the sleep of the not-quite-innocent. She is about to lean across and kiss the wiry black strands of hair where it breaks at the nape of his neck and curls back towards his ears, when she hears footsteps on the floorboards outside. An instant later, the chamber door shakes to a presumptive hammering.

Nicholas sits up beside her with a start. He stares about him, still half-snared in sleep. ‘Who calls?’ he demands. ‘Is Her Majesty sick?’

No reply comes. But the hammering goes on.

Bianca is first out of bed. She throws back the coverlet that smells as though it’s been kept in a leaky chest since Elizabeth’s coronation. When she lifts the door latch, she comes eye-toforehead with little Robert Cecil, the queen’s principal Secretary of State.

‘So this is where they put you,’ he says, taking note of the spartan interior. ‘If you’re called again, I shall have a word with the Lord Chamberlain. You deserve better.’

‘Why the alarm, Sir Robert?’ Nicholas asks, now standing at Bianca’s shoulder. ‘Does Her Grace require a doctor?’

Cecil gives a tight smile that dies half-formed. ‘Not the queen, Nicholas. Someone at Cecil House. My barge is being made ready as we speak. Mistress Bianca may travel with us as far as Bankside if she chooses. Either way, be at the water-stairs in ten minutes.’

Still sleepy, Nicholas is about to ask if Cecil’s father, Lord Burghley, has taken a turn for the worse. Then he remembers: old Burghley died in August.

‘May I ask who is sick? And the nature of the malady?’ he enquires as Bianca hurries to fetch his shirt and hose. ‘Not one of your children, I hope.’

‘No,’ says Robert Cecil curtly, turning on his heels. ‘Ten minutes. No longer.’

The gilded Cecil barge is already approaching the royal dockyard at Woolwich before either Nicholas or Bianca gets round to wondering why a man of Robert Cecil’s standing felt the need to deliver his summons in person.

3

‘And another thing— Nicholas! Are you listening to me?’

The slapping of the water against the hull of the Cecil barge brings Nicholas out of a semi-slumber. To his right the gardens of the Inner Temple run down to the riverbank, with black-gowned students studying their law books in the shade of the trees. To his left lie the open fields between Southwark and Lambeth. Ahead, the Thames swings sharply south towards Westminster. He wonders if he’s been dozing ever since they stopped at Blackfriars to let Bianca go ashore.

‘Yes, Sir Robert. Of course I am,’ he says brightly, trying to imply he’s been wide awake all the while.

‘That wife of yours—’

Nicholas feels a jab of disquiet in his stomach. Mr Secretary Cecil has tolerated Bianca’s perceived heresy – her Catholic faith – for as long as Nicholas has been in his service, first as an intelligencer, latterly as his children’s physician. More than once he has used it to coerce Nicholas into accepting a difficult commission. Nicholas wonders if, now that he’s frequently in the queen’s presence, Robert Cecil has decided it’s time to reconsider his forbearance.

‘What of her, Sir Robert?’

‘Her name,’ Cecil says, the irritation evident in his tone. ‘Her name.’

‘Bianca?’

‘You’re being obtuse, sirrah. Not Bianca – Merton.’

‘What’s amiss with it? It’s an English name. It’s her father’s. Would you rather she called herself Caporetti, after her Paduan mother?’

Cecil gives him the sort of look a weary schoolmaster might give a pupil who simply will not grasp simple Latin declension. ‘I’d rather she called herself Shelby. Goodwife Shelby.’

‘Oh, now I understand,’ says Nicholas, resisting a smile.

Cecil raises a cautionary finger. ‘It is an abomination to go around refusing to acknowledge her own married name. It implies her husband has no governance over his household.’

Now there’s no holding back a grin. ‘Sir Robert, I regret to inform you that a husband could have no more governance over Bianca’ – a glance up at the dark clouds gathering in the western sky – ‘than you have over that approaching storm.’

A look of resigned bewilderment sweeps across Cecil’s face. ‘For a yeoman’s son, you have a very odd understanding of tradition and propriety,’ he says, shaking his head. Then, apparently defeated, he adds, ‘You dwell now in Southwark, I think, yes?’

‘At the Paris Garden, yes.’

‘Then I recommend your attendance when next Master Shakespeare has his Shrew playing at the Rose. You might learn something.’

It is as close to humour as Nicholas has seen Cecil get. He says tentatively, not wanting to disappoint, ‘Master Shakespeare is often at the Jackdaw. I suspect he used Bianca as a muse for his Kate.’

A sudden gust of wind ruffles the dense black frizado weave of Cecil’s gown. ‘You may jest at my expense, Nicholas. But be warned: Her Majesty has a habit of taking it badly when young men she favours have the temerity to wed without her approval. She never forgave the Earl of Leicester for marrying that Knollys woman in secret. I suggest that you refer to your wife – within her hearing at least – as Goodwife Shelby. It would be best for all of us.’

‘I shall tell her, Sir Robert,’ Nicholas says, bringing his smile under control. ‘In all civil company, Goodwife Shelby it shall be. But I cannot promise I will be able to persuade Bankside to think of her as anything other than Bianca Merton.’

‘That I could abide to suffer,’ Cecil says with a sigh of resignation, ‘given that Her Majesty is unlikely to express a sudden desire to visit a tavern or a bawdy-house.’ He turns his head to watch a pair of swans glide past. ‘While we’re on the subject of names, I have one other for you to keep in the back of your mind: Robert Devereux.’

‘Why should I have a care for the Earl of Essex?’

‘Because he has a long memory.’

‘He’s shown no sign that he even recalls who I am.’

When Cecil turns his face towards him again, Nicholas can see a parental concern in his eyes, even though the two men are of similar ages.

‘Nevertheless, you would do well not to rouse him,’ Cecil tells him. ‘Even though you were exonerated of that false charge of seeking to harm the queen, he will not have forgotten the matter. You may well find yourself in his company at court. So I would advise against expressing any ludicrous and unworthy ideas about religious toleration that Goodwife Shelby – or her husband, for that matter – may have picked up while they were away in Padua.’

‘You have my word on it, Sir Robert.’

‘I’m relieved to hear it.’

The two men fall into a contrived silence. Up ahead, a grand house with sloping gardens is coming into sight, a jetty thrusting out into the river. As the bargemen port their oars, Cecil glances up at the darkening sky. ‘Another storm on its way – out of Ireland, by the look of it. It will not be the first the Devil has sent us out of that place.’ As he stands, gathering his gown about his crooked body as if to hide it, he adds, ‘What you see here, let it remain in your memory – never on your tongue. Understand?’

Now, thinks Nicholas, I am to discover why the queen’s principal Secretary of State has called me away from Greenwich in such a hurry. Because up until now, he has steadfastly refused to utter a single word on the matter.

For all he can tell, the warren of passages below Cecil House have been dug out of the ground by a race of ancient creatures, half-man, half-mole. The walls are only partly bricked. The floor is cold and moist. Nicholas is not overly tall, but even he feels the compulsion to duck. Ahead of him three servants form a human wall in front of a small door. They are big fellows, too well built for serving at table. Like him, they have adopted an uncomfortable stoop. Robert Cecil is the only one walking with his head up.

‘Is the brute restrained?’ he asks, his voice echoing in the confined space.

‘He is, Sir Robert. With ankle irons.’

‘Then open up.’

One of the servants wields a heavy key. The others set themselves ready to prevent whatever ferocious animal is caged inside from springing free. With a tortured groan of its old hinges, the door is opened. The three servants enter at a crouch, one after the other; there is no space to do otherwise. When whatever lies beyond is no longer deemed a danger, one of them signals to Robert Cecil that it is safe to go inside. Nicholas is the last in.

The chamber is even plainer than the one at Greenwich Palace. It has the furtive smell of human sweat and unwashed clothes, and the same oppressively low ceiling as the corridor that serves it. The sole source of light comes from a tiny semicircular window set into the apex of the vaulted outside wall.

Nicholas has long known that great men like Cecil keep such chambers in their grand houses. They are the useful antechambers to the Tower, where men with ill will in their hearts towards the realm and its queen can make a full and frank confession of their sins, without recourse to the hot irons and engines of agony they will surely face later – if they fail to seize the opportunity so generously on offer here. Nicholas himself has spent a few uncomfortable hours in such a chamber, at Essex House. It was four years ago, when an enemy falsely denounced him to Devereux for plotting to poison the queen.

Not that Robert Cecil looks much like a man who keeps company with torturers. The queen’s principal Secretary of State has a tapering, scholarly face tipped by a little stab of beard. There are lines etched around the wide, full-lidded eyes that were not there when Nicholas left for Padua four years ago, and the skin beneath has started to sag a little, even though Cecil is the younger of the two by a year. There is a melancholy in the face, now. Nicholas attributes it to two bereavements: the death of Sir Robert’s young wife, Elizabeth, and that of his father, Lord Burghley, the queen’s oldest and most trusted advisor.

‘Does he have a name?’ Nicholas asks as he regards the figure lying before him on an unfurnished wooden cot set directly below the skylight. The pale light illuminates the man’s pallid face like a martyr in an altar painting.

‘Not to you, Nicholas,’ Cecil says pleasantly.

Nicholas nods in understanding. If he does not know his patient’s name, how can he later swear before an inquiry that any particular man was ever in Cecil House?

The man on the cot is younger than Nicholas by a decade, around his middle twenties. He is naked, the sinewy limbs suggesting a rural origin not dissimilar to Nicholas’s own, a childhood in the fresh air, honest labour in the field. Like Nicholas, he is dark-haired, though instead of Nicholas’s wiry curls this man has long, soft locks that might gently curtain his face if they were not matted and tangled with what Nicholas takes to be river weed. He is conscious but unmoving, save for the occasional shiver of the puckered white skin. Only the eyes are mobile. Nicholas can see no obvious sign of injury.

‘What ails him?’ he asks.

‘He’s a traitorous Irish papist rebel – that’s what ails him,’ Cecil tells him, as though he was describing a particularly untrainable deerhound.

‘Am I permitted to make a closer observation?’

‘That is why we are here.’

Chained by one ankle to the bed frame, the man remains as still as a corpse as Nicholas approaches. His head is tilted slightly, the long hair swept underneath and providing the only pillow. Now Nicholas can see dark bruises around the neck, raw weals around the wrists. Through cracked and slightly parted lips, the breath comes and goes in a slow, feeble tide, at odds with the muscular limbs. The man’s darting eyes are the only other sign of animation in the whole body. They show how he despises himself for his weakness – but not nearly as greatly as he despises those who have weakened him.

‘How did he come to be like this?’

The largest of the Cecil servants gives Nicholas a sheepish look. ‘He went for a swim, sir.’

‘He threw himself off my water-stairs,’ Sir Robert explains, glancing at the servant for confirmation. ‘Isn’t that so, Latham?’

‘He was bound at the wrists,’ Latham says defensively. ‘But he’s a strong fellow and the rope was wringing wet. When he jumped, he took me by surprise.’ He opens his big hands to show the red rope-marks on his palms.

Cecil raises one hand to lay a reassuring slap on Latham’s shoulder, accentuating the imbalance of the principal secretary’s crooked shoulders. ‘Perhaps it would be best if you explain to Dr Shelby what passed.’

Latham does his best to look consoled. ‘When we was on the water-stairs the prisoner asked where we was taking him. I told him ’twas the Tower, on account of how he’s proving somewhat constipated of tongue. Next we know, he throws hisself head-first into the river. When we fished him out again, he was palsied.’

‘Palsied?’

‘At first it were just his legs,’ Latham says. ‘I thought he was playing us for fools, so I gave him several stout kicks to bring him to his feet. But he couldn’t raise hisself. By the time we’d carried him back to the house, his arms had gone, too. Now it’s only those eyes what move. I reckon they’ll only stop their filthy jigging when the axe falls.’ A glance at his fellows to see if they appreciate his wit. ‘An’ even then I wouldn’t put money on it.’

‘Did you see him strike anything when he went into the water?’ Nicholas asks.

Latham shakes his head. ‘That part of the river is as thick as my wife’s pottage, sir. But I knows for a fact the masons left some old stones there when they rebuilt Lord Burghley’s chapel. You can sees them when the tide is out.’

‘So he could have struck his head against them when he dived in?’

‘It’s possible, sir.’

Nicholas stands over the cot. He reaches out and asks the man to grasp his hand. He gets no response. No movement – except the eyes, which fix on Nicholas’s with a loathing that takes his breath away.

And then he speaks – a short, guttural snarl in a language Nicholas has never heard before.

‘It’s his heathen Irish tongue,’ Robert Cecil says. ‘I’m told he hasn’t spoken any other since he was taken.’

‘When was that? And where?’

‘A fortnight since – in Ireland. He was caught trying to sneak into Dublin. He’s one of the Earl of Tyrone’s traitorous rogues. It is my belief he intended to assassinate the Lieutenant-General, the Earl of Ormonde.’

Nicholas asks to borrow Latham’s dagger.

‘What do you intend, Nicholas?’ Cecil says with a doubting lift of an eyebrow. ‘I have fellows properly trained for hard questioning.’

Without answering, Nicholas kneels at the patient’s feet. He inspects the arches for signs of beating. The skin, though hard and yellowed, shows no bruising. Whatever inducement to talk Latham and his colleagues have already extended, it hasn’t been made to the feet. Levelling the dagger, he presses the tip of the blade gently against the flesh of the right sole. The foot does not move. He presses again, more firmly than before. A small globule of blood blooms around the tip of the blade and trickles down over the calloused heel. Still the foot does not move.

‘May we speak privily, Sir Robert?’ Nicholas says, returning the dagger to Latham. Outside in the corridor he says, ‘What exactly is it you want of me?’

‘I would have thought that obvious, Nicholas. I want you to restore our friend to a better resemblance of health.’

‘So that you can have him tortured more efficiently?’

Cecil gives him a patronizing frown. ‘Well, there isn’t much point in torturing him if he’s dead, is there?’

For a moment Nicholas says nothing. He waits until his temper is under control before speaking again. ‘I am a physician, Mr Secretary. I have sworn an oath to do no harm.’

‘Very laudable. But that doesn’t apply to papist rebels, does it?’

Nicholas cannot prevent a sharp, cynical laugh escaping his lips. ‘Sir Robert, if I may speak bluntly—’

‘I’ve come to expect nothing less.’

‘You know full well that I gained my doctor’s gown at Cambridge. I’ve spent three years at the Palazzo Bo, one of the most liberal universities in Italy, studying anatomy under Professor Fabricius. I am a good friend of Signor Galileo Galilei, the eminent mathematician. The queen herself seeks my opinions on matters of physic and seems approving of them—’

‘Does this have any bearing on our friend downstairs?’

‘I am not beyond understanding matters of state,’ Nicholas protests. ‘Indeed, you would not have made me one of your intelligencers if I was. But I’m sorry – I cannot treat a man merely in order to deliver him to a greater harm. I refuse to be an executioner’s lackey.’

Cecil holds his gaze for a moment without replying. Then he beckons Nicholas to follow him up the steep stone stairs, his crooked little body bounding upwards with surprising agility.

They emerge into an oak-panelled hallway, fresh rushes strewn on the floor. An open door gives onto a terrace bordered by high privet hedges. The late-morning air is cool and smells of wood-smoke from a fire the gardeners have lit somewhere down towards the river. Cecil studies Nicholas like a father trying to gauge if an errant son is worth redeeming.

‘I think it’s time you and I had a little talk,’ he says.

Like everything about Mr Secretary Cecil, his pace around the terrace is urgent, driven. His gown ripples over his uneven back like black water burbling over rocks. Lengthening his stride to keep pace, Nicholas notices the wind is picking up, the clouds gathering. The storm is coming closer.

‘There isn’t time for me to summon the Bishop of London to give you a personal sermon on the duties we owe to our sovereign,’ Cecil tells him. ‘But now that Her Majesty is – apparently – favouring your continued presence, there are some things you must understand.’

‘Things? What manner of things?’

‘For a start, your oath to her takes precedence over all others. The queen is England. Your responsibility now is not solely to her as a patient. It is also to the health of her realm. And at this moment that health is in peril.’

Nicholas falters in his stride. Is Cecil suggesting the queen is stricken with a secret malady? Is that what this is about?

And then Cecil says something that in any tavern in England would stop the conversation dead.

‘We must accept the fact, Nicholas, that the queen cannot live for ever.’