Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: The Jackdaw Mysteries

- Sprache: Englisch

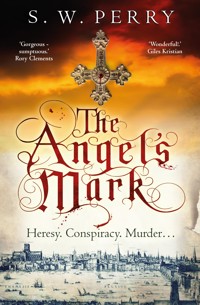

'WONDERFUL!' GILES KRISTIAN 'SUMPTUOUS' RORY CLEMENTS 'GRIPPING' ANNE O'BRIEN ________________________ Heresy. Conspiracy. Murder... London, 1590: Amidst a tumultuous backdrop of Spanish plotters, Catholic heretics and foreign wars, Queen Elizabeth I's control over her kingdom is wavering. And a killer is at work, preying on the weak and destitute of London... Idealistic physician Nicholas Shelby becomes determined to end these terrible murders. Joined in his investigations by Bianca, a beautiful but mysterious tavern keeper, the pair find themselves caught in the middle of a sinister plot. With the killer still at large, Bianca finds herself in terrible danger. Nicholas's choice seems impossible - to save Bianca, or save himself... 'Wonderful! Perry's Elizabethan London is so skilfully evoked, so real that one can almost smell it.' Giles Kristian 'An engaging Elizabethan thriller' Sunday Times READERS LOVE THE ANGEL'S MARK 'A gripping, intelligent historical mystery' ***** 'Fabulous start to a series that I will definitely be keeping on with' ***** 'Exceptionally entertaining!' ***** 'Among the best historical novels I've ever read' ***** 'If you're a Sansom fan, you'll love this' *****

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 611

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Published in hardback in Great Britain in 2018 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © S. W. Perry, 2018

The moral right of S. W. Perry to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 78649 494 8E-book ISBN: 978 1 78649 493 1

Printed in Great Britain.

CorvusAn imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House26–27 Boswell StreetLondonWC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

For Jane

Medicine is the most noble of the Arts, but through the ignorance of those who practise it… it is at present far behind all the others.

HIPPOCRATES

… lay that damned book aside, and gaze not on it, lest it tempt thy soul.

CHRISTOPHER MARLOWE,The Tragicall History of Dr Faustus

Contents

Title

Copyright

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

Historical note

Author’s note

The Serpent’s Mark

Tilbury, England. Winter 1591

Part 1: The Physician from Basle

1

Praise for The Angel’s Mark

Landmarks

Cover

Title

Start

1

London, August 1590

He lies on a single sheet of fine white Flanders linen. Eyelids closed, plump arms folded across his swollen infant belly, he could be a sleeping cherub painted upon the ceiling of a Romish chapel – all he lacks is a harp and a pastel cloud to float upon. The sisters at St Bartholomew’s have prepared him as best they can. They’ve washed away the river mud, plucked the nesting elvers from his mouth, scrubbed him cleaner than he ever was in life. Now he stinks no worse than anything else the watermen might haul out of the Thames on a hot Lammas Day such as this.

Male child, malformed in the lower limbs, some four years of age. Taken up drowned at the Wildgoose stairs on Bankside. Name unknown, save unto God. So says the brief report from the office of the Queen’s Coroner, into whose busy orbit – twelve miles around the royal presence – this child has so impertinently strayed.

The chamber is dark, unbearably stuffy. A miasma of horse-dung, salted fish and human filth spills through the closed shutters from the street outside. Somewhere beyond Finsbury Fields a summer thunderstorm is boiling up noisily. Plague weather, says present opinion. If we escape it this year, we’ll be luckier than we deserve.

The chamber door opens with a soft moan of its ancient hinges. A cheery-looking little fellow in a leather apron enters, his bald head gleaming with sweat. He carries a canvas satchel trapped defensively against his body by his right arm, as though it were stuffed full of contraband. Approaching the child on the table, he begins to whistle a jaunty song, popular in the taverns this season: ‘On high the merry pipit trills’. Then, with the exaggerated care of a servant preparing his master’s table for a feast, he places the satchel beside the corpse, throws open the flap and proceeds to lay out his collection of saws, cleavers, dilators, tongs and scalpels. As he does so, he polishes each one on a corner of the linen, peering into the metal as though searching for hidden flaws. He is a precise man. Everything must be just so. He has standards to maintain. After all, he’s a member of the Worshipful Company of Barber-Surgeons, and while he’s here in the Guildhall of the College of Physicians – a surprisingly modest timber-framed building wedged between the fishmongers’ stalls and bakers’ shops to the south of St Paul’s churchyard – he’s on enemy ground. This rivalry between the meat-cutters and the balm-dispensers has existed, or so they say, since the great Hippocrates began tending patients on his dusty Aegean island.

After two verses, the man stops whistling and engages the child in a pleasant, one-way conversation. He talks about the weather; about what’s playing at the Rose; whether the Spanish will try their hand against England again this summer. It’s a ritual of his. Like a compassionate executioner, he likes to imagine he’s strengthening his subject’s resolve for what lies ahead. When he’s done, he leans over the child as though to bestow a parting kiss. He places his left cheek close to the tiny nostrils. It’s the final part of his ritual: making sure his subject is really dead. After all, it won’t reflect well if he wakes up at the first slice of the scalpel.

‘Who are you planning to cut up for public sport today, Nick?’ shouts Eleanor Shelby to the lathe-and-plaster wall that separates her from her husband. ‘Some poor starving fellow hanged for stealing a mackerel, I shouldn’t wonder.’

For several days now Eleanor and Nicholas have communicated only through this wall, or via scribbled note passed secretively by their maid Harriet. Whenever Nicholas approaches the door of the lying-in chamber, Eleanor’s mother Ann – who’s come down from Suffolk to oversee the birth and ensure the midwife doesn’t steal the pewter – snarls him away. She’s convinced that if he gets so much as a glimpse of his wife he’ll let in the foulness of the London streets, not to mention extreme bad luck. Besides, she tells him crossly whenever she gets the chance, who’s ever heard of a husband setting eyes on his wife during her confinement? Imagine the scandal!

To add to Nicholas’s present misery, every church bell from St Bride’s to St Botolph’s begins to chime the noonday hour, the latecomers making up by effort what they’ve lost in time-keeping. Now he must shout even louder if his wife is to hear him.

‘It’s learning, Sweet. Cutting up is what East Cheap butchers do in their shambles. This is a lecture, for the advancement of science.’

‘Where any passing rogue may peer in over the casement for free. It’s worse than a Southwark bear-baiting.’

‘At least our subjects are dead already, not like those poor tormented creatures. Anyway, it’s a private dissertation. No public allowed.’

‘Insides are insides, Nick. And, in my opinion, that’s where they should stay.’

Nicholas slips his stockinged feet into his new leather boots, tugs out the creases in his Venetian hose and wonders how to say farewell before the bells make conversation through the wall impossible. Normally there’d be the usual passionate endearments, followed by a lot of letting go and grabbing back, kisses interrupted and then jealously resumed, breathless promises to hurry home, a final reluctant parting. After all, they’ve been married scarcely two years. But not today. Today there is the wall.

‘I can’t tarry, Love. You know what Sir Fulke Vaesy thinks of tardiness. There’s bound to be a line somewhere in the Bible about punctuality.’

‘Don’t let him bully you, Nick. I know his sort,’ comes Eleanor’s voice, as if from a great distance.

‘What sort is that?’

‘When you’re the queen’s physician, he’ll grovel to you like a lapdog.’

‘I’ll be seventy by then! Vaesy will be a hundred. What kind of physician makes a centenarian grovel?’

‘The kind whose patients don’t pay their bills!’

Smiling at the muffled peal of Eleanor’s laughter, Nicholas shouts a final farewell. Nevertheless, his leave-taking feels hurried and incomplete, practically ill-starred.

At first sight, you would not take the young fellow stepping out of his lodgings at the sign of the Stag and into the dusty heat for a man of physic. Beneath a plain white canvas doublet, whose points today are left unlaced for ventilation, his body is that of a hardy young countryman. A coil of black hair spills ungovernably beneath the broad rim of his leather hat. And even if this were midwinter and not blazing August, his doctoral gown – won after a lengthy struggle against a whole battery of disapproving Cambridge eyebrows – would still be tucked away, as it is now, in the leather bag slung over one shoulder.

Why this unusual modesty, given that in London a man’s status is known by what he wears? He would probably tell you it’s to protect the expensive gown from the ravages of the street. A truer answer would be that even after two years of practising medicine in the city, Nicholas Shelby can’t quite help thinking that a Suffolk yeoman’s son has no right to wear such exotic apparel.

Keeping up a sweaty trot in the heat, Nicholas passes the Grass church herb-market and heads down Fish Street Hill, towards the College Guildhall. He squirms with embarrassment when the clerks there bow extravagantly. He’s still finds such deference uncomfortable. In a side-chamber he takes the gown from his bag and, like a guilty secret, wraps it around his body. He enters the dissection room by one door, just as Sir Fulke Vaesy comes in by the other.

He’s made it, with barely moments to spare.

Edging in beside his friend Simon Cowper, Nicholas expects to find the subject of today’s lecture is one of the four adult felons fresh from the gallows that the College is licensed to dissect each year, just as Eleanor had indicated. Only now does he see the tiny figure lying on the linen sheet, surrounded by the barber-surgeon’s instruments.

And Simon Cowper, knowing that Nicholas is an expectant father, cannot bring himself to look his friend in the eye.

Sir Fulke reminds Nicholas of a Roman proconsul preparing to inspect hostages from a conquered tribe. Resplendent in his fellow’s gown with its fur trim, a pearl-encrusted silk cap upon his head, he’s a large man with a fabled appetite for sack, goose and venison. He rises from his official chair and towers over the tiny white figure on the table. But Vaesy has no intention of getting his hands bloody today. It is not for the holder of the Lumleian chair of anatomy to behave like a common butcher jointing a carcass in the parish shambles. The actual cutting of flesh will be done by Master Dunnich, the cheery little bald fellow from the Worshipful Company of Barber-Surgeons.

‘A healthy womb is like the fertile soil in Eden’s blessed garden,’ Vaesy begins, to the biblical accompaniment of summer thunder, much closer now. ‘It is the wholesome furrow in which the seed of Adam may take root—’

Is he delivering a lecture or a sermon? Sometimes Nicholas finds it hard to tell the difference. Through the now un-shuttered windows comes the smell of the street: fish stalls and fresh horse-dung. On each sill rest the chins of passers-by, craning their necks to peer in and gawp. The heat has made this lecture less private than Nicholas imagined.

‘However, this infant, found by the watermen in mid-river just yesterday, is the inevitable issue of disease, physical and spiritual. The child has clearly been born’ – the great anatomist pauses for effect – ‘monstrous!’

The beams of the Guildhall roof seem almost to flinch. Nicholas has a sudden protective urge to wrap the naked child in the linen sheet and tell Vaesy to stop frightening him.

By ‘monstrous’, Vaesy means crippled. The description seems overly brutal to Nicholas, who tries hard to study the child dispassionately. He notes how the withered legs arch inwards below the knees. How the yellowing toes entwine like stunted vines. Clearly he could not have walked into the river by himself. Did he crawl in whilst playing on the bank? Perhaps he fell off one of the wherries or tilt-boats that ply their trade on the water. Or maybe he was thrown in, like an unwanted sickly dog. Whatever the truth, something about the little body strikes Nicholas as odd. Most corpses fished from the river, he knows, are found floating face-down, weighted by the mass of the head. The blood should pool in the cheeks and the forehead. But this boy’s face is waxy white. Maybe it’s because he hasn’t been in the water long, he thinks, noting the absence of bite-marks from pike or water rat.

Is that a small tear on one side of the throat? And there’s a second, deeper wound – low down on the calf of the right leg, like a cross cut into old cheese. A dreadful image enters Nicholas’s mind: the infant being hauled out of the water on the end of a boathook.

‘The causes of deformity such as we see here, gentlemen, are familiar enough to us, are they not?’ says Vaesy, breaking into his thoughts. ‘Perhaps one of you would be so good as to list them? You, sirrah—’

Instantly the eyes of every physician in the room drop to the laces of their boots, to the condition of their hose, in Nicholas’s case to the scars of boyhood harvesting etched into his fingers, to anything but Vaesy’s awful stare. They know the great anatomist will expect at least ten minutes’ dissertation on the subject, all in faultless Latin.

‘Mr Cowper, is it not?’

Of all the victims Vaesy could have chosen, poor Simon Cowper is the easiest: forever muddling his Galen with his Vesalius; ineptly transposing his astrological houses when drawing up a prognosis; when letting blood, more likely to cut himself than the patient. He stands now in the full glare of Vaesy’s attention like a man condemned. Nicholas’s heart weeps for him.

‘The first, according to the Frenchman, Paré,’ Cowper begins nervously, wisely choosing a standard text for safety, ‘is too great a quantity of seed in the father—’

A snigger from amongst the young physicians. Vaesy kills it with a look of thunder. But it’s too late for Simon Cowper; his delicate fingers begin to drum nervously against his thighs. ‘S-ss-secondly: the mother having sat too long upon a stool… with her legs crossed… or… having her belly bound too tight… or by the narrowness of the womb.’

For what seems like an age, Vaesy torments the poor man by doing nothing but arching one bushy eyebrow. When Cowper exhausts his slim fund of knowledge, the great anatomist calls him a fuddle-cap and reminds him of his own favourite medical catch-all. ‘The wrath of God, man! The wrath of God!’ To Vaesy, sickness is mostly explained by divine displeasure.

Cowper sits down. He looks ready to weep. Nicholas wonders how wrathful God has to be to allow a crippled child to end up on Vaesy’s dissection table.

Two attendants step forward. One removes the starched Flanders linen, the other the corpse. Now Nicholas can see that the table it covered is little more than a butcher’s block with a drain drilled through it, a wooden bucket set beneath the hole. In place of the linen is set a sheet of waxed sailcloth, a vent stitched into the centre. From the stains visible on it, it’s been employed in this role before. The dead child is set down again, like an offering upon an altar.

‘The first incision into the thorax, Master Dunnich, if you’d be so kind,’ orders Vaesy to the little bald-headed barber-surgeon.

Immediately the stench of putrefaction fills the air like an old familiar sin. Nicholas knows it well. Even now, it never fails to turn his stomach. At once he’s back in the Low Countries, his first post after leaving Cambridge.

‘Isn’t there enough sickness for you here in Suffolk?’ Eleanor had asked him when he’d told her he was off to Holland to enlist as a physician in the army of the Prince of Orange, thus postponing their marriage.

‘The Spanish are butchering faithful Protestants in their own homes.’

‘Yes, in Holland. Besides, you’re not a soldier, you’re a physician.’

‘I can do some good. It’s why I trained. I fought hard for my doctorate. I won’t waste it prescribing cures for indigestion.’

‘But, Nicholas, it’s dangerous. The crossing alone—’

‘No more dangerous than Ipswich on market day. I’ll be back in six months.’

She had pummelled his arm in frustration, and the knowledge that she was refusing to weep until he’d gone only compounded his guilt.

In the course of that summer campaign Nicholas had witnessed things no man with a soul should ever have to see. Things he will never tell Eleanor about. Sometimes he still dreams of the babe he’d found on a dung heap, tossed there on the tines of a pitchfork for sport by the men of Spain’s Popish army; and the starved corpses of children after the lifting of a siege. When the smell of roasting meat reaches him, he remembers the remains of women and greybeards herded into Protestant chapels and burned alive.

Not that the Dutch troops and their mercenaries had all been saints, not by any means. But he’d learned a lot that summer: how to tell a man his wound is nothing, that he’ll soon be up and supping ale in Antwerp, and sound convincing, when in fact you know he’s dying; how to drink with German mercenaries and still keep a steady hold on a scalpel; how never, ever to gamble with the Swiss… No one had cared then whether he belonged to the appropriate guild. There was no distinction made between physicians who diagnose and surgeons who get their hands bloody. No time to study the astrological implications when a man is bleeding to death before your eyes.

‘Now, gentlemen,’ Vaesy’s voice pulls Nicholas back to the present, ‘if you have studied your Vesalius diligently, you will note the following—’

With the help of his ivory wand and numerous quotations from the Old Testament, the great anatomist takes his audience on a journey around the infant’s organs, muscles and sinews. By the time he finishes, the dead child is little more than a filleted carcass. Dunnich, the barber-surgeon, has opened him up like a spatchcock.

To his own surprise, Nicholas is in a state bordering on numb terror. He thinks, God protect the child Eleanor is carrying from such a fate as this.

But there’s more. There’s the bucket beneath the dissecting table. It’s almost empty. There’s scarcely a pint of blood in it. And then there’s that second wound, the one on the child’s lower right leg, which Vaesy has apparently missed altogether, for the great anatomist has failed to utter a single word about it in all the time he’s been standing over the corpse. Nicholas describes it now in his mind, as if he were giving evidence before the coroner: one very deep laceration, Your Honour, made deliberately with a sharp blade. And a second made transversely across the first – towards its lower point.

An inverted cross.

The mark of necromancy. The Devil’s signature.

The Tollworth brook, Surrey, the same afternoon

The hind turns her head as she sups from the ford, ears pricked for danger. Her arched neck gives a sudden tremble, the way Elise’s own neck used to tremble when little Ralph clung too tight and she could feel his warm breath upon her skin.

She knows I’m close, thinks Elise. And yet she does not fear me. We are the same, this fallow deer and I. We are fellow creatures of the forest, driven by thirst to forget there may be hunters watching us from the trees.

Dragonflies dart amongst the columns of sunlight that pierce the canopy of branches. She can hear the thrumming of their iridescent wings even above the noise the stream makes as it courses over the mossy stones, even above the rumble of distant summer thunder. She sinks to her knees, puts her lips gingerly to the water. It burbles over her tongue, over her skin, flows into her. Cold and sharp. Bliss made liquid.

Elise recalls it was by a stream like this, on another hot summer’s day not long past, that she first succumbed to the delirium that only this cool water can keep at bay. Exhausted, starving, she had imagined the weight she was bearing upon her young back was not her crippled infant brother but the holy cross, and that she was dragging her sacred burden through the dust towards Golgotha…

By a stream like this… on a day like this…

The figure had appeared from nowhere, a silhouette as black as that sudden flash of oblivion you get when, by mistake, you glance into the sun. An angel come down from heaven to save them.

‘Help us,’ Elise had pleaded, peeling poor little Ralph’s withered legs from her back as the desperation overwhelmed her. ‘He cannot walk, and I cannot carry him another step. In the name of mercy, take him—’

Forcing the memory from her mind, Elise slakes her thirst in the ford like the wild animal she has become. And as she drinks, she cannot forget that it was her own desperate wail of need that had alerted the angel to their presence. If she had not cried out, perhaps the angel would not have seen them. Perhaps all that followed would have stayed firmly in the realm of bad dreams.

If she were able, Elise would shout a warning to the hind: ‘Drink swiftly, little one – the hunters may be nearer than you think!’

But Elise cannot cry out. Elise must remain silent; if needs be, for ever. A single careless word, and the angel might hear her and return – for her.

2

Vaesy’s desk is strewn with sheets of parchment covered with symbols and figures. At one end stands a collection of glass vessels. Some, notes Nicholas, contain the desiccated remains of animals, others coloured oils and strange liquids. At the other end is an astrologer’s astrolabe and a beaker of what looks suspiciously like urine – the astrolabe to measure the position of the heavenly bodies when the owner of the bladder relieved himself, the urine to reveal by its colour whether his bodily humours are in balance. Nicholas can make out, seen through the beaker’s glass, the skeletal hand of a monkey held together with wire, distorted by the yellow liquid into a demon’s claw. He has entered a place where medicine and alchemy mix – a perfectly unremarkable physician’s study.

‘You asked to see me, Dr Shelby,’ the great anatomist says pleasantly. Out of the dissection room, he seems almost amiable. ‘How may I be of service?’

Nicholas comes straight to the point. ‘I believe the subject of your lecture today was murdered, Sir Fulke.’

‘Mercy, sirrah! That’s a brave charge,’ Vaesy says, easing himself out of his gown and setting down his pearl-trimmed cap.

‘The child was thrown into the river to hide the crime.’

‘I think you’d best explain yourself, Dr Shelby.’

‘I can’t imagine how the coroner failed to notice the wound, sir,’ Nicholas says. He can, of course – laziness.

‘Wound? What wound?’

‘On the right calf, sir. Small, but very deep. I suspect it might have severed the posterior tibial canal. If not staunched quickly, it would eventually have proved fatal.’

‘Oh, that wound,’ says Vaesy breezily. ‘A hungry pike, most likely. Or a boathook. Immaterial.’

‘Immaterial?’

‘The Queen’s Coroner did not make the child available for dissection so that you, sirrah, could study wounds. The wound was immaterial to the substance of my lecture.’

‘But there was almost no blood left in the body, sir,’ Nicholas points out, as diplomatically as he can. ‘The child must have bled out while alive. Blood does not flow post mortem.’

‘I’m perfectly well aware of that, thank you, Dr Shelby,’ says Vaesy, his easy manner beginning to harden.

‘I do not believe the wound was made by any fish, sir. There were no other bite marks on the body.’

‘So you’ve decided the alternative is murder, have you? Are all your diagnoses made so swiftly?’

‘Well, he didn’t drown. That’s obvious. There was very little water in the lungs.’

‘Are you suggesting the Queen’s Coroner does not know his job?’ asks Vaesy icily.

‘Of course not,’ says Nicholas. ‘But how are we to explain—’

Vaesy raises a hand to stop him. ‘The note from Coroner Danby’s clerk was clear: the child was drowned. How he came to such an end is no concern of ours.’

‘But if he was bled before death, then he was murdered.’

‘And what if he was? The infant was an unclaimed vagrant. He was of no consequence.’

If Vaesy is so familiar with the good book, thinks Nicholas, how is it that mercy and compassion are apparently such alien concepts to him?

‘Shouldn’t we at least try to identify him – find out if he had a name?’

‘I know exactly what his name is, young man.’

‘You do?’ says Nicholas, caught off-balance.

‘Why, yes. His name is Disorder. His name is Lawlessness. He was the offspring of the itinerant poor, Dr Shelby. What does it matter to us if he drowned or was struck down by a thunderbolt? Had he lived, he would surely have hanged before he was twenty. At least now he has made a contribution to the advancement of physic!’

Nicholas tries to curb his growing anger. ‘He was once flesh and blood, Sir Fulke. He was an innocent child!’

‘Never fear, there’ll be plenty more where he came from. They breed like flies on a midden, Dr Shelby.’

‘He was someone’s son, Sir Fulke. And I believe he was murdered. You have influence – delay the interment of the remains. Ask the coroner to convene a proper jury.’

‘It’s far too late for that, sirrah. The child is already delivered to St Bride’s.’ Vaesy’s veined cheeks swell as he gives Nicholas a patronizing smile. ‘He should thank us, Dr Shelby. He’s better off in consecrated ground than as carrion cast up on the riverbank.’ He takes Nicholas by the elbow. For a moment the young physician thinks he’s found some previously unsuspected empathy in the great anatomist. He’s wrong, of course. ‘Your wife, Dr Shelby – I hear she is expecting a child.’

‘Our first, Sir Fulke.’

‘Well, sirrah, there you have it: the wholly natural sensitivities of the expectant father.’

‘Sensitivities?’

‘Come now, Shelby, you’re not the first man to get in a lather at a time like this. I once knew a fellow who became convinced his wife would miscarry if he ate sturgeon on a Wednesday.’

‘You think this is all in my imagination?’

Vaesy puts a hand on Nicholas’s shoulder. The sleeve of his gown smells of aqua vitae. ‘Dr Shelby,’ he says unctuously, ‘I hope one day to see you as a senior fellow of this College. I trust by then you will have learned to lay aside all unprofitable concern for those whom we physicians are in no position to help – else we would weep tears for all the world, would we not?’

The wholly natural sensitivities of the expectant father.

‘The arrogant, over-stuffed tyrant!’ mutters Nicholas as he runs towards Trinity church, the brim of his leather hat pulled tight over his brow. It’s raining hard now, one of those intense summer squalls that mist the narrow lanes and send the coney-catchers and the purse-divers heading for the nearest tavern to pursue their thievery in the dry. A crack of thunder rolls like a cannonade down Thames Street. ‘He thinks I’m overwrought. He thinks I’m no tougher than one of those novice sisters at St Bartholomew’s.’

But there’s a fragment of truth in what Vaesy has said. In his heart Nicholas knows it. The memory of that pitchforked child; his witnessing of the dissection; the Grass Street wall he cannot breach – all these have done nothing to ease his fears for Eleanor and the child she carries.

After one of Vaesy’s lectures it is the habit of the young physicians to celebrate their survival by getting fabulously drunk. Their favoured tavern is to be found at the sign of the White Swan, close by Trinity churchyard. The knock-down has been flowing a while when Nicholas arrives, eliciting angry mutterings from the other customers about young medical men being more ungovernable than apprentice boys on a feast day. Nicholas throws his dripping hat onto the table as he sits down, noting morosely the once-jaunty feather drooping like the banner of a defeated army. ‘Am I the only one?’ he asks as he signs to a passing tap-boy. ‘Did anyone else see those wounds?’

‘Wounds?’ echoes Michael Gardener, a Kentish fellow who’s already looking like a well-fed country doctor at the age of twenty-four. ‘What wounds?’

‘Two deep incisions on the poor little tot’s leg. The right leg. Vaesy missed them completely.’

‘Master Dunnich probably made them by accident; you know how careless barber-surgeons are,’ says Gardener, running his fingers through his luxuriant beard. ‘That’s why I never let them near this.’

‘Did you see them, Simon?’

‘Not I,’ says Cowper, his face shiny from the ale. ‘I was too busy trying not to catch Vaesy’s eye again.’

Gardener raises his jug to Nicholas and, with a hideously lewd grin on his face, calls out, ‘Enough of physic! A toast to our fine bully-boy! Not long now and he’ll be back in the saddle.’

‘He’s a physician,’ someone in the group laughs. ‘It’ll be the jumping-shops of Bankside for our Nick!’

Simon Cowper, now quite in his cups, affects an effeminate simper. ‘Oh, sweet Nicholas, why must you pass the hours in such low company, while I must content myself with sewing and the psalter?’

Nicholas is about to tell Simon just how wrong he is to caricature Eleanor in such a manner, but the words dissolve on his tongue. Why spur his friends to further teasing? He sighs, gives a good-natured smile and empties his tankard.

And, just for a while, the dead child on Vaesy’s dissection table fades from his thoughts.

Dusk, and Grass Street little more than a dark slash of overhanging timber-framed houses cutting through the city towards the river near Fish Hill.

Nicholas lies alone on his bed, his head resting on the bolster, his eyes towards the wall. He pictures Eleanor lying snugly on the other side, barely inches from him but so inaccessible that she might as well be in far-off Muscovy. She’s asleep now, a welcome respite from the heaviness that keeps stirring within her.

Eleanor is the thread in the weave of his soul. She is the sunlight on the water, the sigh in the warm wind. The lines are not his. He’s borrowed them from the overly poetic Cowper, his own sonnets being distinctly wooden. Eleanor is the perfect bride that his elder brother Jack used to describe in their moments of hot youthful fancy: impossibly beautiful, wholly devoid of any amorous restraint, in need of urgent rescue and usually with a name from mythology.

For Jack, the myth turned out to be a yeoman’s daughter named Faith: extremities like the boughs of a sturdy oak, popping out acorns regularly every other year. But Nicholas, to his immense and perpetual astonishment, has found the real thing; though if there was any rescuing needed, it was Eleanor who performed it. He can’t quite believe his luck.

Often, in his mind, he relives the moment they first danced a pavane together. It was at the Barnthorpe May Fair. Thirteen years of age, within a week of each other. He the prickly second son of a Suffolk yeoman, she the lithe-limbed, freckled meadow sprite, as hard to hold in one place as gossamer caught on a summer breeze. They’d known each other since infancy. Nicholas calls it his first lesson in medicine: sometimes the remedy for a malady can be staring you in the face, but you’re just too stupid to see it.

For the past two hours now Harriet, their servant, has played a secret game of go-between. Whenever Ann and the midwife insist that Nicholas and Eleanor stop talking, Harriet finds a reason to visit the two chambers: a little warm broth for Eleanor… some mutton and bread for Nicholas… floor rushes that need changing before morning… piss-pots to be emptied… She uses these excuses to carry whispered messages, taking to these tasks with all the furtive skill of a government intelligencer carrying encrypted dispatches.

‘How is young Jack, my sweet?’ Nicholas had asked in the last spoken exchange between husband and wife, sensing the growing drowsiness in Eleanor’s voice even through the wall.

‘Grace is fine, Husband – thank you.’

Jack, if it’s a boy – named for Nicholas’s elder brother; Grace, if it’s a girl, in memory of Eleanor’s grandmother.

When he’d spoken again he’d received no reply, only a muttered, ‘For mercy’s sake, hush!’ from his mother-in-law.

At the end of the working day Nicholas Shelby has never hesitated to discuss a difficult diagnosis with his wife, or to make her laugh loudly by mimicking some particularly pompous or difficult patient. But tonight, with Eleanor so close to her time, how can he even mention what he’s seen at the Guildhall? He must endure it alone, with only the sound of his own breathing for company.

He touches the plaster, letting his fingertips rest there a while. Though the wall is barely thicker than the span of his hand, it feels as cold and as impenetrable as a castle’s.

Suddenly, he fears the night to come. He fears he will have bad dreams. Dreams of dead infants hoisted on Spanish pitchforks. Dreams of a child bled dry and floating on the tide. Whole columns of grey, empty-eyed, lifeless children marching across a barren landscape that is half muddy Thames riverbank, half flat Dutch polder. And every one of them his and Eleanor’s. More than anything, he fears his own imagination.

In fact, he sleeps surprisingly soundly. He stirs only when the lodging’s prize cockerel beats – by a good half-hour – the bell at Trinity church.

Unable to see Eleanor, and with no patients to visit the next morning, Nicholas seeks out the clerk to William Danby, the Queen’s Coroner. While it might not matter to Fulke Vaesy that a nameless little boy could end his short life in such a manner, in the present circumstances it matters greatly to Nicholas Shelby.

The wholly natural sensitivities of the expectant father.

Damn me for it, if you dare, he tells an imaginary Sir Fulke as he heads for Whitehall. Some of us still remember why we chose healing for a profession.

The clerk to the Queen’s Coroner is a precise, bespectacled man in a gown of legal black. Nicholas finds him in a room more like a cell than an office, filling out the weekly city mortuary roll. He writes with a slow, methodical hand on a thin ribbon of parchment, carefully transferring the names of the dead from the individual parish reports.

What must it be like, Nicholas wonders as he waits for the man to acknowledge him, to spend your day tallying up the deceased? What happens if you misspell a name? If a Tyler in life becomes a Tailor in death, simply through inattention, are they still the same person to posterity that a wife or a brother remembers? Such mistakes can easily happen, especially in times of plague, when the clerks can’t write fast enough to keep accurate records.

Names… Jack for a boy. Grace for a girl. Names unknown, save unto God…

‘The boy they found at the Wildgoose stairs—’ he begins, when at last the clerk looks up.

The man lays down his nib. He places it well to one side of the parchment roll to prevent an inky splatter obliterating someone’s existence. He ponders a moment, trying to place one child amongst so many. Then, as though he’s recalling some unwanted piece of furniture, ‘Ah yes, the one we allowed to the College of Physicians—’

‘I wondered if he had a name yet.’

‘If he had, I can assure you we would not have agreed to the request for dissection.’

‘Someone must know who he was, surely.’

The clerk shrugs. ‘We asked the watermen who found him. And the tenants in the nearby houses. None admitted to knowing the boy. Perhaps he was a vagrant’s brat. Or a mariner’s child, fallen off one of the barques moored in the Pool. Sadly, there are many such taken from the Thames at this time of year: fishing for eels, grubbing for meat scraps at the shambles. They wander into the water and the next thing they know—’ He makes a little explosive puff through his lips to signify the sudden watery end to someone’s life.

Nicholas waits a moment before he says, ‘I believe he was murdered.’

A defensive flicker of the clerk’s eyes. ‘Murdered? On what evidence do you make such a claim?’

‘I can’t prove it, but I’m almost certain he was dead before he went into the water. If nothing else, justice demands an investigation.’

‘Too late for justice to worry herself much now,’ the clerk says with a shrug. ‘I assume the College has already had the remains shriven and buried at St Bride’s.’

‘So I am told.’

‘Then what do you expect me to do – beg the Bishop of London for a shovel, so we can dig him out from Abraham’s bosom?’

The pain on Nicholas’s face is clear, even in the gloom of the little chamber. ‘He was somebody’s son,’ he says falteringly. ‘He had a father, and a mother. A family. He should at least have a proper headstone.’

The clerk is not an uncaring man. The names he writes on the mortuary rolls are more to him than just a meaningless assembly of letters. His voice softens. ‘Have you passed by the Aldgate or Bishopsgate recently, Dr Shelby? There are more beggars and vagrants coming into the city from the country parishes than ever before. Some bring disease with them. Many will die, especially their infants. That is a sad fact indeed. But it is God’s will.’

‘I know that,’ says Nicholas.

‘Then there’s the tavern brawls, the street-fights after the curfew bell rings, children and women falling under waggon wheels, wherry passengers slipping on the river stairs…’

‘I appreciate Coroner Danby is a busy man—’

The clerk picks up his pen. ‘And thank Jesu the pestilence has spared us so far this summer. No, sir, I fear there will be no time to spare for investigating the death of a nameless vagrant child. There are barely enough hours in the day to arrange inquests for those who do have a name.’

Nicholas has often treated patients whose grasp on reality is failing. He’s prescribed easements for those who hear voices, or see great cities in the sky where the rest of us see only clouds. He’s treated over-pious virgins who say they converse nightly with an archangel, and stolid haberdashers who tell him a succubus visits them in bed after sermon every Sunday to relieve them of their seed. He doesn’t believe in possession. He believes in it about as much as he believes it necessary for a physician to cast an astrological table before making a diagnosis, something most doctors he knows seem to consider indispensable. Yet, as he leaves Whitehall, it has not occurred to him that his natural concern for Eleanor’s safety is a tiny breach in the wall of his own sanity. Or that the soul of a dead infant boy might have discovered the crack.

Their father has taught the Shelby boys never to leave a task unfinished. Sown fields do not reap themselves. Nicholas visits the sisters at St Bartholomew’s hospital who prepared the infant for Vaesy’s examination. Their recollection is hazy. They welcomed three dead infants to the mortuary crypt on the day before the lecture, none of them memorable.

He speaks to the watermen down by the Wildgoose stairs on Bankside, where the child was pulled from the river.

‘Why, sir, we know the very fellows who found the body,’ one of the watermen tells him. Then, with heartfelt regret, ‘But working on the water don’t pay for itself, Master—’

It costs Nicholas twice the price of a wherry fare to get the names. And when he locates them, the men turn out to have been somewhere else on the day.

I thought I’d been in London long enough not to get gulled so easily, he thinks as he walks back across the bridge. He feels dispirited. Oddly ill-at-ease. He longs to share his fears with the one person he knows would listen sympathetically. But that’s impossible. How can he dare even whisper of child-murder when Eleanor is so close to her time?

Three days after his visit to Coroner Danby’s clerk at Whitehall, Nicholas attends a formal lunch at the College of Physicians. Harriet has strict instructions not to linger if the baby comes – she is to hurry by the fastest route to the Guildhall, and no stopping to gossip on the way.

Today’s guest of honour is John Lumley, Baron Lumley of the county of Durham and of various estates in Sussex and Surrey. It is Lord Lumley who, by the queen’s gracious licence, had endowed the College of Physicians with an annuity of forty pounds a year – from his own purse, of course, not hers. It pays for a reader in anatomy. Sir Fulke Vaesy is the present incumbent.

The agenda is wearyingly familiar to Nicholas: first the prayers, then the food – roasted pigeon, salmon and plum porridge. Then an address by the College’s distinguished president, William Baronsdale. The heat of the day and the heaviness of his formal gown lead Nicholas to wonder if he can fall asleep without anyone noticing.

Baronsdale rises with ponderous solemnity, his ruff starched to the unyielding hardness of ivory. He’s barely able to move his head. He looks to Nicholas like a ferret stuck, up to the chin, in a drainpipe.

‘My noble lord, sirs, gentlemen,’ he begins sonorously, ‘it is my duty to acquaint you with the gravest threat to face this College in all its long and august history.’

His drowsiness instantly banished, Nicholas wonders what impending calamity Baronsdale means. Has there been an outbreak of pestilence he hasn’t heard about? Has Spain sent another Armada? Surely Baronsdale isn’t going to mention the chaos everyone fears will come with the queen’s death, given that she cannot now be expected to provide the realm with an heir. Discussion of the subject is forbidden by law. Not even old Dr Lopez, Elizabeth’s physician, who at this very moment is wiping his plate with his bread, dares mention it.

This lunch might yet prove more entertaining than I’d expected, thinks Nicholas.

In fact, it transpires that Baronsdale is warning them of a far greater hazard than any of those Nicholas has contemplated. It is this: how to stop the barber-surgeons passing themselves off as professional practitioners, thus impertinently considering themselves the equal of learned physicians.

An hour later, with Nicholas’s eyelids again feeling like lead, the great men of medicine agree on their defence. The nub of it, according to Baronsdale, is that the barber-surgeon uses tools in the practice of his work. He must therefore be a tradesman. In other words, little better than a blacksmith. ‘Why, if everyone who wields a sharp point in their daily toil considers themselves a professional,’ proclaims Baronsdale, ‘there’d be a guildhall, a chapel and a chain of office for the seamstresses!’

Nicholas has an urgent need to talk to the wall at Grass Street again. But there’s no escape for him. Not yet. Baronsdale hasn’t finished. It appears the barber-surgeons are not the only threat facing the College.

‘On Candlewick Street, a fishmonger named Crepin is alleged to be selling unauthorized cures for lameness, at two pennies a pot,’ he whines. ‘On Pentecost Lane, one Elvery – whose trade is that of nail-maker – is said to be concocting a syrup to cure the flux. He prescribes it without charge. Doesn’t expect so much as a farthing.’

Mutters of disapproval from around the table.

‘There is even a woman—’

More than a few gasps of horror.

‘Yes, a common Bankside tavern-mistress. Goes by the name of Merton. They say she concocts diverse unlicensed remedies, without any learning whatsoever!’ Baronsdale wags a finger to signify the Christian world is teetering of the edge of the pit of hell. His neck twists rigidly in his ruff as though he’s trying to unscrew his head. ‘We must put an end to these charlatans,’ he says gravely, ‘lest the learning of fifteen centuries be hawked outside St Paul’s Cross for a loaf of bread or a pot of ale!’

The applause is warm and appreciative. But Nicholas notices the guest of honour, John Lumley, seems unperturbed by these dire warnings of impending catastrophe. In fact, is that a yawn the rather sorrowful-looking patron of the chair of anatomy is trying to stifle?

Though Nicholas has only observed John Lumley from his own lowly orbit, Lumley’s reputation is well known to him. He is the queen’s friend, though he’s served time in the Tower for once desiring a Catholic monarchy. He’s a man of the old faith, yet in possession of a mind always on the search for new knowledge. His great library at Nonsuch Palace is said to be the match for any university library in Europe. And though he funds the chair of anatomy from his own purse, he’s not a physician. Which, thinks Nicholas, might just make him the perfect man to turn to.

But how, exactly, does a junior member of the College raise the subject of infanticide with one of its most senior – especially after his betters have gorged themselves on roasted pigeon and salmon, fine Rhenish wine and flagons of self-congratulation?

With confidence. That’s the answer, Nicholas decides as he waits in the Guildhall yard while around him the servants of the more successful physicians prepare for their masters to depart. Get to the point right away. Don’t hang back. Tell him what you saw.

He spots Lord Lumley’s secretary, Gabriel Quigley, standing aloof to one side. Quigley is a bookish fellow in his mid-thirties. The severe folds of his gown serve only to accentuate his angular frame. His thinning hair falls loosely over a brow marked by traces of the small-pox. He looks more like a fallen priest than a lord’s secretary.

‘Would you do me a service, Master Quigley?’ Nicholas asks. ‘I’d be grateful for a brief audience with Lord Lumley.’

Quigley’s reply tells Nicholas in no uncertain terms that a lord’s secretary is considerably nearer to God than a mere physician, any day of the week. ‘His lordship is a busy man. What would be the subject of this audience, were he to grant it?’

‘A matter of great interest to an eminent man of physic,’ says Nicholas, biting his tongue. It’s better than ‘The violent overthrow of this place and all who dwell in it’, which is what he’s been considering since before the plum porridge was served.

‘My lord, I wondered if I might speak to you about Sir Fulke Vaesy’s recent lecture,’ Nicholas begins, with a respectful bend of the knee, when Quigley brokers the meeting.

‘The drowned boy-child?’ Lumley recalls. ‘Coroner Danby took not a little convincing over him.’

‘A most unusual subject, my lord.’

‘Indeed, Dr Shelby. One likes to feel that when Sir Fulke dissects a hanged criminal, the fellow is making some sort of reparation for his offences by adding to our understanding of nature. But a poor drowned child is quite another matter. Still, I always say we men of learning should not let our natural sensitivities get in the way of discovery.’

Natural sensitivities. Nicholas prays Lumley isn’t going to turn out to be as lacking in them as his protégé. ‘My lord, on the subject of the infant – I couldn’t help but notice—’

At that very moment, to his horror, Sir Fulke Vaesy himself emerges from the College hall. Striding over, he bows as graciously as his girth will allow and booms, ‘A grand lunch, my lord! And all the better for the dessert: barber-surgeons cooked in a pie!’ He glances at Nicholas. ‘How now, Shelby? Wife foaled yet?’

‘Any day, Sir Fulke,’ Nicholas says lamely. He can hear the sound of doors slamming. Doors to his career. And it will be Vaesy who’ll be doing the slamming, if Nicholas says in the great anatomist’s hearing what’s been on his mind these past few days.

‘Dr Shelby was about to mention your lecture, Fulke.’

‘Was he now?’

Nicholas bites his tongue. ‘I was going to say how instructive I found it, Sir Fulke.’

Vaesy beams, thinking good reviews can only make Lumley’s forty pounds a year that bit more secure.

Lumley pulls on the hem of his gloves in preparation for departure. ‘Was there anything else, sirrah? Master Quigley suggested you wished to speak to me on an important matter.’

Nicholas clutches at the only straw left to him: delay. ‘Perhaps I might be allowed to correspond with you, my lord – to seek your views on matters of new physic. I’d value them greatly.’

To his relief, Lumley seems flattered. ‘By all means, Dr Shelby. I shall look forward to it. I always like to hear from the younger men in the profession – minds less set. Don’t you, Fulke?’

Vaesy doesn’t seem to understand the question.

As Nicholas walks away he can almost hear the drowned boy whispering his approval: You are my only voice. Don’t let them silence me. Don’t give up.

On his way home Nicholas stops by the East Cheap cistern to wash the dust from his face. It’s hot, he’s eaten too much, listened to enough worthy back-slapping to last him a decade. Close to the fountain stands a religious firebrand reciting the gospels, punctuating his readings with dire warnings of man’s imminent destruction, to anyone who will listen. Few bother. A lad in a leather apron leads a fractious ram by a chain in the direction of Old Exchange Lane. A rook alights on the branches of a nearby tree and begins to caw loudly.

These are the minor details that will stay seared into Nicholas’s mind for ever. They have no particular importance. They are mere dressing for the centrepiece of the masque: Harriet.

She’s hurrying towards him, not even bothering to lift the hem of her dress from the filth of the street. He opens his mouth to call out.

Boy or girl? Jack or Grace?

He doesn’t care which. A boy will be the greatest physician in Europe, a girl the mirror of her mother. But the words cannot fly his mouth. They are glued there by the awful expression on Harriet’s flushed face.

Silence.

Elise has sworn never to allow a single word to pass her lips, no matter how long she lives or how desperate she becomes. A single careless word might bring the angel back.

Silence is a hard restraint. It is by no means her natural state. Her mother used to tell her that God Himself would soon go deaf from her constant chattering. But that was before Mary Cullen had descended into her own mute world of drunken insensibility, informing her on the way that God had crippled her little brother Ralph as a punishment for Elise’s ungovernable tongue. Now silence is Elise’s only protector.

She would beg for food, but she knows what will happen if she does: people will spit at her, throw stones that buzz like bees past her head or strike her painfully in the back. They will call for a man with a whip to chase her away, or threaten her with a branding, even having an ear sliced from her head to mark her for the vagrant they say she is.

So Elise does not beg. Instead, she lives off scraps of food thieved from window ledges and unattended tables, sleeps on the hard earth beneath the briars. She is utterly alone, without even little Ralph for company now. The only human voice she hears and does not flee from is her mother’s, whispering to her the old story: that there is somewhere better than here, my darling, and if you go down to the Tabard and beg a cup of arak on credit, I will tell you how to get there.

3

What follows Nicholas Shelby’s return to Grass Street is as predictable as the unravelling of a scarf when an errant thread is tugged, and just as unstoppable.

Ann cannot meet his wildly searching gaze. She turns from her son-in-law as though he’s a ranting madman. But this time neither she nor the midwife bars his entrance to the lying-in chamber.

Eleanor’s skin is feverish to the touch. His fingers come away chilled by her sweat. The flesh around her belly is as hard as iron. It does not yield to the pressure of his palm. Her eyes are closed, her breathing little more than the panting after a lost fight. She seems already to have put a great distance between them.

‘There is no sign of imminent birth,’ the midwife tells him. ‘Barely a single drop of blood discharged from the privy region – just some small quantity of her water.’ She makes it sound as though things are only a little awry, not quite as expected, no real need to worry. Do I sound like that, he wonders, when I’m delivering grim news?

It’s the first time he’s entered this chamber since it was closed off for the birthing. It feels like a foreign land to him. He glances to a collection of dark-red pebbles at the foot of the bed. ‘What are those supposed to do?’

‘They are holy stones, stained by the blood of St Margaret,’ the midwife replies, not a little frightened by the intensity in his stare.

‘She needs medicine, woman, not superstition,’ he shouts, sweeping them away with an angry wave of his hand. They rattle on the uneven floorboards like noisy accusations. ‘Harriet!’ he calls. The girl appears at his side. She seems to have caught some of Eleanor’s deathly pallor. ‘Run to the apothecary by All Hallows for a balm of lady mantle and wort. Hurry!’

‘No balm can alter God’s will, Nicholas,’ says Ann, laying a hand on his shoulder. ‘It is not good to fight what is ordained.’

Ann is not a thoughtless woman; she’s already lost two children of her own, a boy in childbirth, another daughter who lived less than a month. Trials, she believes, are sent by God to test our mettle. Her words are intended to bring strength to her son-inlaw. Instead, they only make him angrier.

‘It might help induce the birth,’ he shouts. ‘It has to be better than prayer and holy stones!’

Eleanor is fading away before his eyes. But it takes almost two full days. And not once during that time does Nicholas get so much as the paltry comfort of knowing she’s aware he’s beside her – not a squeeze of his hand, not even a slack smile of recognition. Nothing.

When he’s not sitting on a stool by the bed, moistening her lips with a wet cloth, he’s to be found leafing frantically through his books: Galen’s Art of Physic, Vesalius’s Fabrica, half a dozen more. He’s searching for some scrap of redeeming knowledge that he thinks he might have forgotten. But he’s forgotten nothing. Eleanor is going to die not because of what Nicholas has forgotten, but what he never knew.

On the second day, around eight in the evening, in his desperation he even considers a caesarean delivery. He’s heard about such a procedure, though he’s never actually seen one performed. And he knows that even if the child is saved, the mother will die. To his knowledge, there has only ever been one instance of both surviving, and that was in Switzerland. How can he possibly plunge a knife into the belly of his beloved Eleanor in order to save their child? But if he doesn’t…

Her breathing is getting slower and deeper. Now and again comes a sound like the one his winter boots make when he steps by mistake into the mud of the Finsbury fields. He grips Eleanor’s cold hand and screws his eyes as though peering into the sun.

Why did they wait so long to call me?

Why did I go to that wretched feast?

Why do the swiftly passing minutes of her final struggle mock me so cruelly? What good is my knowledge now?

Why can’t I do anything?

Why?… why?… why?

The day after the funeral service for mother and child, held at Trinity church, Nicholas stands in the lying-in chamber at Grass Street. Now it’s just another empty room – a sloping floor that creaks when you walk on it, irregular pillars of oak holding up a low sagging ceiling, a small leaded window giving onto the lane, the shutters open for the first time in weeks.

Just another room.

He puts out one hand to touch the uneven plaster. He thinks of the recent nights he’s spent on the other side of this wall, straining his senses to catch Eleanor’s soft, feminine murmurs, longing to be with her. He stares at his splayed fingers pressed against the surface, barely recognizing them as his own. The room is silent now, empty. He could call to the wall for eternity and never receive a reply. Weak with grief, he lets go of the wall and sinks to his knees.

Just another room.

Someone else’s hand.

Someone else’s tragedy.

His gaze comes to rest on a patch of plaster beside the door frame, where he and Eleanor had planned to make a mark each birthday to record their child’s growth. They’d agreed to stop at thirteen. If it’s a boy, they’d decided, he’ll grow too fast. If it’s a girl, at thirteen she’ll think such fancies childish. Now the wall will stay unmarked for ever.