Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

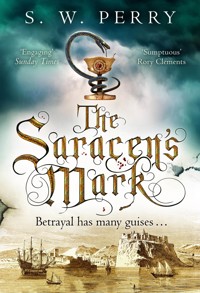

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Krimi

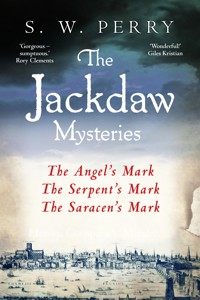

- Serie: The Jackdaw Mysteries

- Sprache: Englisch

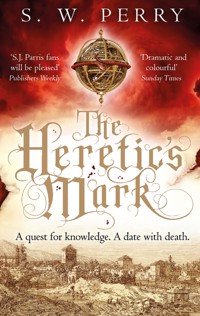

'DRAMATIC AND COLOURFUL' SUNDAY TIMES 'MY FAVOURITE HISTORICAL CRIME SERIES' S. G. MacLEAN ------------------------------------------------------ England, 1593: Five years on from the Armada and Elizabeth's kingdom seems secure. But there is always a plot afoot... Robert Cecil, the Queen's spymaster, needs Nicholas Shelby - reluctant spy and maverick physician - to embark on an undercover mission once again. One that he can't refuse, if he wants to keep Bianca Merton safe. Crossing the seas to Marrakesh in search of a missing informer, Nicholas hunts the dingy back alleys and dazzling palaces for the truth. But his search reveals a deadly conspiracy, one far more difficult to survive than he'd ever imagined. And back in London the plague has returned, ravaging the streets and threatening everything he holds most dear... Praise for S. W. Perry's Jackdaw Mysteries 'S. W. Perry is one of the best' The Times 'No-one is better than S. W. Perry at leading us through the squalid streets of London in the sixteenth century' Andrew Swanston 'Historical fiction at its most sumptuous' Rory Clements READERS ARE RAVING ABOUT THE SARACEN'S MARK 'Terrific' ***** 'I just can't get enough of Nicholas and Bianca' ***** 'Superb, with so many twists and turns' ***** 'Please write more!!' ***** 'A real page turner' *****

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 671

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Also by S. W. Perry

The Jackdaw Mysteries

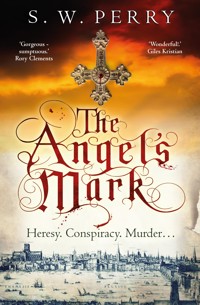

The Angel’s Mark

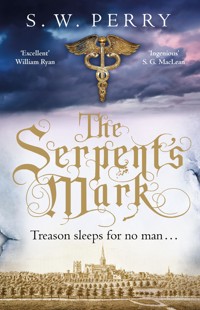

The Serpent’s Mark

The Heretic’s Mark

Published in hardback in Great Britain in 2020 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition published in 2021.

Copyright © S. W. Perry, 2020

The moral right of S. W. Perry to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 78649 899 1

E-book ISBN: 978 1 78649 898 4

Printed in Great Britain

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

For Jane, as always

O, let the heavens give him defence against the elements, for I have lost him on a dangerous sea…

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, OTHELLO

In 1589 the Sultan of Morocco sent an envoy to London. He received a rapturous welcome, even though at the time comprehension of the mysterious Islamic world was, at best, confused. Whatever the country of his birth, to the English a Muslim was a Moor, a Turk, or a Saracen…

PART 1

The Kissing Knot

1

Marrakech, Morocco. March 1593

In the moment before they caught him, Adolfo Sykes was dreaming of oranges.

It was an hour after sunset, the third night of the time that some amongst the Moors called `Ushar, when the moon was almost full. In the gardens of the Koutoubia mosque the sellers of holy texts had packed away their books. The professional storytellers had departed, their audiences dispersed. From their high minarets the muezzins had called the city to the al-maghrib prayers, leaving the medina to the shadows and the scavenging dogs.

He loved the city at this time of night. He felt enfolded within its protective red walls. The cooling breeze from the Atlas Mountains filled the streets not with the scents of spices and human sweat, but with cleansing citrus.

Until he’d come to the land of the Moor, Adolfo Sykes had barely seen an orange, let alone tasted the succulent flesh. But now, after three prosperous years in Morocco, this agent of the Barbary Company of London – its founding stockholders the noble Earls of Warwick and Leicester – was ready to believe that paradise itself might smell like one vast orchard of orange trees.

He had almost reached his destination, the city hospital, the Bimaristan al-Mansur. Its high mud-brick walls were barely twenty paces ahead of him. And then this agreeable reverie was shattered in a single heartbeat.

Out of the night stepped two figures, their heads bound in voluminous kufiyas – a pair of monstrously fat-headed demons conjured up by some devilish jinn. In that instant Adolfo Sykes realized he had been a dead man from the moment he’d left his lodgings on the Street of the Weavers.

He had thought himself unobserved, no easy accomplishment for a small, somewhat bow-legged half-English, half-Portuguese merchant with a threadbare curtain of prematurely white hair that clung to the sides of his otherwise-unsown pate. An involuntary grunt of surprise escaped his lips. He stopped. Then he did what most are inclined to do when they have stumbled into what they suspect to be mortal danger: he came up with hasty reasons to believe he hadn’t.

They are fellow Christian traders, he told himself confidently. Or Jewish moneymen from the el-Mellah quarter, those clever fellows without whom trade between Moor and European would seize up like an axle without grease. Whoever they were, they were not, under any circumstances, real or imagined, assassins.

The night suddenly seemed colder, despite the djellaba he was wearing, woven from the best English wool, and evidence – if any were needed – of the superiority of his merchandise. Fighting against a rising tide of panic, Sykes glanced quickly over his shoulder. A second pair of shrouded figures was standing barely two paces behind him, cutting off his retreat.

What happened next began with a moment of awkward comedy. First there was an odd little dance, as though five latecomers to a feast had all converged at the one remaining empty chair. Sykes, being a diminutive fellow and as wiry as a Barbary macaque, dodged sideways. He had a brief glimpse of himself as a free man, speeding through the darkened streets to safety – then to a ship that would carry him back to England where, as far as he knew, no one intended him violent bodily harm. Then a grasping hand caught a fold of his djellaba and a sideways kick swept his little bowed legs from under him. He went face-down onto the dirt, a plaintive grunt bursting from his lungs. He felt warm blood pool in his jaw, and the weight of a man’s knee in the small of his back, almost breaking him. The darkness took on an even thicker patina as the man leaned over him, enveloping him in the folds of his robe like a falcon mantling over a stunned hare.

Even then, Adolfo Sykes was not yet fully ready to acknowledge the truth: that they had known he was coming, known where to lie in wait. That he’d been driven like game, the way the Berber tribesmen drove the desert gazelle towards their bows. In his tolerable Arabic he gasped, ‘Purse… left side… my belt – take it. If God wills it, it’s yours.’

The answer ripped away the last shreds of self-delusion.

‘Do not insult us, Master Sykes; we are not common thieves,’ said a voice very close to his left ear. ‘It is not your purse we desire; it is the secret that you keep hidden from us in your infidel heart.’

English. Spoken with an Irish accent, by someone barely grown to manhood. The very last language he’d been expecting to hear.

Turning his head painfully towards the speaker, Sykes saw a cheek as pale as porcelain in the moonlight, a cheek flecked with a boyish attempt at a beard.

The voice then spoke some words in Arabic, presumably for his companions’ benefit. It was not the unrefined language of the streets, Sykes noticed abstractly, but formal, classical Arabic, as if it had recently been learned by rote at the feet of a teacher. Sykes picked out the phrases ‘It is him… it’s the infidel who steals from the faithful.’

This offended Adolfo Sykes almost as much as the assault on his body. He had never stolen from anyone. Ask his customers. Ask the Christian merchants. Ask the Jews from the el-Mellah. Ask the forty God-fearing English merchants who comprised the body of the Barbary Company – licensed by the queen’s seal to hold the monopoly of trade between the princely states of Morocco and England – fine upstanding men, every last one of them. Men who counted themselves amongst the most forward-thinking in London, and who would expel him at the merest suggestion of stealing.

But what troubled him more than the slander was the voice: an executioner’s voice, devoid of mercy.

Rough hands hauled Sykes to his feet. Making a poor attempt at bluff, he protested, ‘I am the factor for the Barbary Company of London. As such, I am protected by the mercy of His Majesty Sultan al-Mansur. I have his written word upon it. I can show you.’

And it was true, after a fashion. The passport was in his lodgings, penned by one of the sultan’s army of clerks, though as it was written in Arabic – which he could speak, but not read – it might, for all Sykes knew, be a shopping list.

The answer was brutally unapologetic. First there was a blow to the side of his head that made his knees buckle. Then they bound his hands and gagged him. He could tell at first bite that the gag was of a wholly inferior-quality cloth. Probably homespun by Berber tribesmen. It seemed to Sykes like the final, deliberate insult.

They manhandled him roughly through the same narrow doorway cut into the mud-brick wall of the Bimaristan from which they had emerged. He didn’t struggle. They were young and much too strong for him. They had the law of the desert on their side: the weak always die first; and resisting only prolongs the agony.

Once inside, Sykes saw by the meagre light of an oil lamp an old watchman sitting in an alcove. His furrowed skin was as dark as argan bark, his beard white, like a crescent moon on a starless night. He left his seat, turned away and dropped to his knees, taking up the posture of a Moor at prayer. Sykes understood at once: this was not religious devotion, this was done so that he could later claim never to have witnessed the furtive, nocturnal arrival of a bound and gagged European.

For the place of execution they had chosen a room seemingly at the very heart of the Bimaristan, a chamber tiled from floor to ceiling with intricate mosaics, each tiny square of stone as polished as a mirror glass. He heard the one with the Irish accent engage in a brief but tense conversation in Arabic with his companions. He could understand only intermittent words, but he knew they were fortifying their own courage – boys on the verge of manhood, steeling themselves for a harsh rite of passage. He heard the prayer begin. ‘All hu akbar…’

In a way, he was glad it was to be here, in this little bejewelled chamber. Because cut into the flat ceiling was an opening in the shape of a six-pointed star, a window onto the limitless night, and once more he could catch the scent of oranges on the air. Paradise. Waiting for him. And all he had to do now was steel himself for the journey.

2

The south bank of the Thames river, London. One month later

In the small hours of a deathly-still April morning two miles downriver from Westminster, three men climb silently from a private wherry. Caped against the bitter cold in heavy gabardines, they strike east from the Mutton Lane river stairs. They are heading for Long Southwark, guided through the empty lanes by the twisting flames of a single torch. Bankside is deserted. The unseasonably cold night is too raw even for thieves and house-divers. The timbers of the close-set houses rear out of the mist like the ribs of a fleet of galleys wrecked in the surf.

At the gatehouse on the southern end of London Bridge they come across the night-watch, warming their tired bones around a brazier that burns like a beacon warning of invasion. The three men pause, but only to confirm the address they have been given. There is a practised hardness in their faces that hints that they might be bearing steel beneath their cloaks. The watch lets them pass without question. They know government men when they see them. Arrests are always best made at times like this, when the subject is too sleep-befuddled to put up a fight.

Entering a lane close to the sign of the Tabard Inn, the three men count off the houses until they reach a modest two-storey property of lathe and plaster, close to a row of trees that marks the western boundary of St Thomas’s hospital for the poor. With no show of pleasure at having reached their goal after such an uncomfortable journey their leader begins to hammer violently on the front door, as though its planks and hinges are personally responsible for the night’s discomforts.

Nicholas Shelby wakes with a start. He feels the rhythmic blows through the floorboards, through the frame of his bed, through the straw in the mattress, even in his bones. It is the sort of hammering that constables employ when arresting traitors – or calling physicians from their warm beds to tell them that the plague has finally crossed the river into Southwark.

He has been awaiting a call like this since the first cases of the new pestilence came to light last year. So far, the outbreak has stayed confined to the poorer lanes on the other side of London Bridge. But that hasn’t stopped the Courts of Chancery, Wards, Liveries and Requests taking themselves off to Hertford to consider their business in healthier surroundings. So far, the liberty of Southwark has escaped. In the Bankside taverns, more than one wag has made the connection between the decrease in lawyers and the absence of plague south of the river where the bawdy-houses lie.

But Southwark has not escaped entirely. The Lord Mayor has ordered the closing of the playhouses and the bear-pits. As a consequence, an unwelcome lethargy has descended on the southern shore of the Thames. The purse-divers and coney-catchers have lost half of their trade at a stroke. In the stews, there are whores who have had only themselves for company since Candlemas, and the kindlier church wardens have stopped asking them their trade, when assessing the need for charity. Cynics say there are only two types of public places the authorities dare not shut, for fear of riot: churches and taverns. It all seems to Nicholas a grim prelude for what would otherwise be a time of joy and festivity – an impending wedding.

Fully awake now, he opens his eyes to the semi-darkness of his rented room. On the clothes chest a single candle stands close to guttering, as squat and fat as a lump of yellow clay thrown on a potter’s wheel. It fills the room with the smoky smell of mutton grease. A film of moisture on the inside of the window, and the absence of anything other than watery blackness beyond, tells him dawn must still be some hours off. It is that hollowed-out time of the night when it is better not to wake, when thoughts unchain themselves, when spirits walk and old men die.

‘The Devil take you and your godless knocking!’

The voice of his landlady, Mistress Muzzle, penetrates the floorboards, caustic enough to strip limewash off a wall. Nicholas hears a wheezing snort of indignation, followed by, ‘I hope this is not one of your patients, Dr Shelby! If it is, I’d be indebted if you would ask them to fall sick at a godlier hour.’

Nicholas knows it will take his landlady a while to reach the front door. She is a woman ill-designed for velocity. Struggling into his hose and shirt, he wonders if he can beat her to it. As he steps out onto the landing, he sees the flicker of an oil lamp moving ponderously through the darkness and hears her voice again, full of injured propriety: ‘Anon! Anon! Do you expect me to open the door in naught but my shift? What manner of place do you think I keep – a bawdy-house?’

Even on Bankside, no one would confuse the upright Mistress Muzzle’s dwelling with a bawd’s premises, thinks Nicholas as he stumbles down the stairs. It is, however, the perfect place on Bankside in which to start a medical practice: one room at street level for seeing patients, accommodation above, and the landlady – the fearsome Mistress Muzzle – safely in her own domain at the rear of the house. The only part they are forced to share is the front door.

In the light from the lamp, her pouchy face has the discomforted look of someone suffering a mild bout of colic. With an indignant explosion of breath and a theatrical jangling of her keys, she opens the door. Over her expansive shoulders, Nicholas can just make out three heads silhouetted against the misty night; a night turned a wet, muddy ochre by the light of a single flickering torch. A disembodied voice reaches him. No apology, just a bald statement: ‘These are the lodgings of Dr Nicholas Shelby. Correct?’

‘I am Dr Shelby,’ Nicholas says, rubbing the sleep from his eyes.

‘You are to come with us – at once.’

‘By whose command?’

‘By Sir Robert Cecil’s command.’

So not the pestilence, then – but a close-enough second.

Mistress Muzzle turns back from the door. Nicholas sees her little eyes flicker over him, full of sudden mistrust. He knows what she’s thinking: a member of the queen’s Privy Council has sent for her tenant in the middle of the night. Therefore, at the very least, he must have poisoned someone. Has he been distributing papist pamphlets instead of medicine? Is he no doctor at all, but a charlatan prescriber of fake elixirs? And more importantly, by taking his rent, is she guilty by association?

For a moment Nicholas enjoys her confusion. But spacious, sanitary lodgings are not easy to find on Bankside.

‘I’m not a wanted felon, Mistress Muzzle. Or a Jesuit – if that’s what concerns you. And I have paid my rent until Trinity term.’

Unconvinced, she turns her head back towards the door and the men in the street. ‘Is Dr Shelby under arrest?’ she asks.

‘Not at the moment,’ says the one holding the burning torch. Wisps of smoke swirl upwards, disappearing into the cold, damp night and making Nicholas think of souls rising from a graveyard. ‘But if you want—’

The hammering has sounded so official that not a single occupant has dared open a window to see what is happening. No one wants to risk witnessing the apprehending of a traitor or the flushing out of a papist priest. Too many questions get asked, and there’s always the chance of being mistaken for an accomplice. Much safer to wait for the public finale on Tower Hill or at Tyburn. And even though he knows himself to be an almost-innocent man, Nicholas can’t help but acknowledge the little wormy knot of cold fear that writhes in his stomach.

‘Do I have time to make myself a little more presentable?’

‘Be quick. This is not an invitation to a revel, Dr Shelby. We have a wherry at the Mutton Lane stairs and the tide will soon begin to ebb. Bring what items a physician might normally have about him.’

‘For what malady?’

‘Sir Robert did not say.’

‘Then how, in the name of Jesu, may I know what to bring?’

The irritation is clear in the man’s terse reply. ‘Whatever else is required, Sir Robert will provide it. Now hurry.’

‘How long will you be away?’ asks Mistress Muzzle.

‘I don’t know. Ask them,’ Nicholas says, nodding at the men in the street. ‘If anyone comes here needing medicine, tell them to seek out Mistress Merton. She’ll be either at the Jackdaw tavern, or at her new apothecary shop on Dice Lane. Bianca will know what to do.’

For the first time that Nicholas has witnessed, since he moved out of the Jackdaw and into Mistress Muzzle’s lodgings, his landlady favours him with a smile. It is the warm, indulgent smile that some women are inclined to, whenever they think of impending nuptials. ‘And if Mistress Merton herself should call here while you are away? What am I to say to her?’

‘That’s easy to answer, Mistress Muzzle. One way or another, I will be back in time for the wedding.’

In the bedchamber of a modest property on Dice Lane, a short distance upriver from Mistress Muzzle’s house, Bianca Merton wakes from a fragile, troubled sleep. She sits up against the bolster, the neckline of her shift damp against her skin. In the darkness she remembers two bodies falling through the night towards the cold, black surface of the Thames. She hears the slow, heavy slap as they enter deep water, the sound of ripples fading, like the tinkling of broken glass on a stone floor. She waits for them to disappear beneath the surface. But they don’t. Their faces stay just below, watching her through the water with the cold, accusing stare of the dead. She squeezes her eyelids tightly shut. If I made a pact with God, she tells herself, when I look again, they will be gone. But if I made a pact with the Devil…

She counts to three and opens her eyes.

To her immense relief, there are no bodies tumbling, just shadows cast by the rushlight burning on the bedside table. A pact made with God, then. A righteous pact, not an evil one. Even so, she wonders if all murderers are troubled by such memories.

Her eyes linger on the crudely painted figures on the far wall, figures that must have triggered the illusion: two men, one prone, the other standing over him. The image is from the New Testament, the parable of the Good Samaritan. This house, she has learned, was previously owned by a Puritan who had wanted furnishings with a biblical theme, but couldn’t afford expensive Flemish tapestries. So instead he hired a man who painted tavern signs to decorate the walls.

They keep her company: Jonah and his whale, in the closet; Lazarus in the pantry; Daniel and the lion in the parlour where she takes breakfast. Daniel looks like a fat Bankside alderman. The lion, conjured from the painter’s imagination, is an animal quite unknown anywhere else on earth. Bianca has learned to tolerate them all, including the Good Samaritan in the bedroom, except on those few occasions when he dances in the rushlight and reminds her of the night, almost two years ago now, when two men did indeed tumble through the darkness below the bridge.

When she had confessed her sin to Cardinal Fiorzi, before he sailed away back to Venice, he had told her that God would forgive her. The men she had led to their deaths were evil men. They had committed vile deeds in the service of Satan, and there was no sin in ridding the world of them. But to Bianca, in spite of all that, they were still men. And now they were dead. Absolution could not alter the hand she had played in their deaths.

She scolds herself. I am not a murderer. I am a Good Samaritan. How many more innocents would have suffered if I had not done what I did? How many penniless Banksiders might have sickened – or, worse, died – if I’d stood by and allowed Nicholas Shelby to die?

At the thought of him, she demurely adjusts her shift where it has slipped over one shoulder, and combs her hair with her fingers to bring at least a little obedience to those heavy, dark tresses that are always at their most ungovernable when she wakes. If he could see her at this moment – Jesu, what would her mother have said at the very idea? – he would think her skin still glowed with the warmth of the Italian sun. But that’s because of the rushlight. She fears that five years of English rain have washed the real colour right out of her, along with almost every other trace of her Paduan upbringing. She touches her neck where it meets the shoulder – a neck that on Monday is swanlike, and on Tuesday as scrawny as the reeds that grow around the Mutton Lane river stairs. Yes, in candlelight a veritable Venus; but in the grey light of a morning in early April?

She consoles herself with the thought that Englishmen appear to like their women looking as pale as a cadaver. Caking your face with ceruse is all the fashion in smart circles. Even the queen paints her features with it, to make her skin as white as the best Flanders linen. Not that you’ll see it on Bankside, save on the faces of the richer whores who favour it to cover up the ravages of the French Gout. She curses herself angrily, and recalls something her mother had often told her: Bianca, my child, never trouble yourself with what a man may think of you. Thinking is not their natural disposition.

Yet even as she stares down the bed to the wainscoting on the far wall, wainscoting that is painted a rich orange, she thinks it would be nice to have a little colour in her face for the wedding.

For once, no one tells Nicholas to sit patiently amidst the panelled elegance of Cecil House – one of the grandest beyond the city walls, set between the river and Covent Garden – until someone remembers his presence. No one instructs him to bide his time while the clerks and the men of law, the intriguers and the intelligencers hurry to and fro. No one mistakes him for a new gardener who has unforgivably stumbled through the wrong door. This time a weary-looking secretary in a black half-cape and gartered stockings shows him directly to Robert Cecil’s study.

The Lord Treasurer’s son has clearly been at work for some time, though dawn has yet to break. Hunched over his desk, his crookedness is smoothed by the night beyond the glass. His little beard cuts a dark wedge out of the neat white ruff that he wears over a doublet of moss-green velvet. To Nicholas, he could be an innocent-faced but malevolent little sprite reading spells from a parchment. Though he is about Nicholas’s age, his eyes are those of a man who has seen all there is to see, good and bad. When he speaks, his voice is like the whisper of a blade drawn from its sheath.

‘Dr Shelby, thank you for agreeing to come.’

It seems a strange thing to say, thinks Nicholas, when you’ve sent three men to drag someone from his bed – especially when you already pay him handsomely to be on call.

‘I am always at your service, Sir Robert,’ he says quietly, wishing it didn’t sound so much like an admission of guilt.

Robert Cecil rises and steps forward from his desk. There is a tension in his little body that almost dares you to recognize its imperfection, to ask him to his face how it is that a small man with a crooked spine can make even the most powerful dance to his tune. Nicholas has heard the tavern-talk: that the queen calls him Elf, or Pigmy. Given that the Cecils know almost everything that occurs in this realm, he wonders how Sir Robert bears the insult. Perhaps his hard carapace is more a defence against life’s slights than against the realm’s enemies.

‘Leave your gabardine there,’ Cecil says, indicating a high-backed chair in the corner. ‘I don’t wish my wife to think I’ve summoned a Thames waterman instead of a physician.’

‘Is Lady Cecil ill?’ Nicholas asks as he unlaces his coat. ‘Why didn’t your man say?’

But Cecil merely regards him with a critical eye. ‘Tell me, Dr Shelby, what exactly is it you spend my retainer on? That is the same white canvas doublet you were wearing when I sent you to spy upon Lord Lumley. When was that – two years past? Are you hoarding my stipend in case the Spanish come again? It won’t save you, you know. They’ll rob you of it and give it to the Pope to expiate their sins. So you might as well spend some of it on a good tailor.’

Nicholas tries not to sound sanctimonious. ‘I spend a little on lodgings and food, the rest I use to subsidize my medical practice, so that Banksiders can afford something better than the usual charlatans who peddle false remedies. In return, I come when you call. It is what we agreed when I accepted your patronage.’

Cecil shoots him a look of mock despair. Then he opens the door and ushers Nicholas through into the panelled corridor. Candles burning in silver sconces throw their two shadows back against the oak wainscoting. In Nicholas’s mind, one shadow is a man climbing the steps to a scaffold, the other a gargoyle watching from the crowd. Why is it, he asks himself, that whenever I’m in this man’s presence, my thoughts turn inevitably towards a violent fate?

At the end of the corridor they stop before a set of doors, their panels carved with the Cecil crest. Sir Robert raps his energetic little fist on the timber and calls out, ‘Madam, are you composed? Dr Shelby has arrived.’

The door opens onto a pleasant chamber hung with shimmering drapes and cushioned as Nicholas would imagine an Eastern harem to be. He remembers the craze for all things Moorish that swept London when the envoy of the Sultan of Morocco visited: Tamburlaine at the Rose theatre, shoemakers turning out oriental slippers, everyone gawping at the sight of dark-skinned men in exotic robes. Even Eleanor had insisted they turn their own chamber Turkish. But that was before…

He pushes the memory from his mind and follows Cecil into the room.

A slight, graceful woman of about thirty sits flanked by four ladies-in-waiting, an empty cradle at her feet. In her lap is a toddler, dressed in an embroidered smock that Nicholas reckons would set back a Southwark labourer the better part of a month’s wages. He has met Lady Elizabeth Cecil, daughter of Lord Cobham and wife to the Lord Treasurer’s son, before. And he knows she does not care much for him.

‘Is there really no other physician in London to attend us, Husband?’ she asks Cecil, putting her arms protectively around the child, who begins to grizzle loudly.

So it’s the son I’ve been called to treat, thinks Nicholas. And his mother doesn’t want me anywhere near him. This could prove a difficult diagnosis.

‘Madam, you know my opinion of doctors,’ says Cecil. ‘I have suffered the best of them, certainly the most expensive. They did nothing for me. I remain as I was born – disjointed. To my mind, I count Dr Shelby among the few honest ones I’ve met. At the very least, he will not lie to us.’

It is the first time Nicholas has heard Robert Cecil speak openly of his condition. He takes it as a cue, looking directly into Cecil’s wife’s eyes.

‘Lady Cecil, let us be open with one another. I assume you have heard what a few of the older Fellows of the College of Physicians say about me.’

His directness takes her by surprise. ‘I have. They say that in some matters of physic you are a heretic.’

A sad smile – quickly mastered. ‘And I do not deny it, Lady Cecil. When I discovered that what I had learned wasn’t enough to save the woman I loved and the child she was carrying, there followed a period when I shunned all reason. I rejected everything I had been taught. I drank myself into insensibility, because it seemed the only medicine I could stomach. I lost my practice, my friends, my livelihood. I slept beneath hedges and I cursed God for letting me wake in the morning. When I recovered my senses – with the help of a woman I can only describe as a ministering angel – I swore I would only practise medicine that I could prove works. If I was to have faith in it, it must be physic whose outcome I could predict with some accuracy. That is an oath I do not intend to break. If it is not enough for you, I am content to return to Bankside and the bed from which your husband’s men so roughly summoned me.’

Shocked by his honesty, Elizabeth Cecil drops her gaze to her son. She gentles him, but he keeps grizzling. ‘I am not sure that recommends you, Dr Shelby, except as a man who loved his wife more than he loved his reputation.’

‘As Sir Robert has just this moment said, madam, I will not lie to you.’

‘Is it true you abjure casting a horoscope before you make a diagnosis?’ she asks.

‘Yes, it is.’

‘Then how do you know what manner of cure is propitious?’

‘I do not believe the stars influence the body nearly as much as is claimed, Lady Cecil.’

‘But that flies in the face of all received wisdom, Dr Shelby.’

‘Perhaps it does. But if you have a pain in your back in January, and after treatment it returns in August, how can the constellations guide me on what medicine I should prescribe? The stars are no longer aligned.’

He can see the confusion in her. Her delicate fingers fuss with the child’s smock.

‘And they say you do not believe in the humours of the body. Is that true?’

‘Until someone can show me a humour, madam, yes, it is. Until I can touch it, examine it, replicate its influence in a reliable manner, I cannot in all faith insist it exists. Besides, it is taught that balancing the humours requires the drawing of blood from certain parts of the body. Would you have me bleed a child of William’s age? He’s barely two, am I right?’

‘Of course not! William is far too young for bleeding,’ she exclaims, more than a little horrified. She clutches the boy to her breast, as if she fears Nicholas will produce a lancet from beneath his doublet and advance upon the infant.

‘But if bleeding works, Lady Cecil, why not bleed a child?’

‘Because… well, because…’

‘A child has blood flowing through its veins, just as the mother has. So if drawing blood is medically sound, why not bleed the child – other than to save it from the discomfort? That is where reason would lead us, is it not?’

He waits until he sees a flicker of self-doubt in her grey eyes.

‘I’m not trying to trick you, madam. The answer is simple: because it doesn’t work. I believe any effect is purely coincidental. I can tell you from my experiences in Holland, as a physician to the army of the House of Orange, that blood is best kept where it is – inside.’

Elizabeth Cecil seems intrigued now, almost enjoying a frisson of sedition. She turns to her husband. ‘Robert, explain yourself: how is it that a man who spends his waking hours seeking out heretics invites one into his house – to administer to his son?’

‘Madam, are you going to let Dr Shelby examine William or not?’

With a sudden obedience that surprises him, Lady Cecil sits the child on the nearest cushion, holding him gently by the arm. But there is nothing obedient in the look she gives Nicholas. ‘Have a care with my son, Dr Shelby. He is not the child of some Southwark goodwife – he is a Cecil’s heir. His grandfather is the queen’s best-loved servant. Harm him’ – a glance in her husband’s direction – ‘and not even her newest privy councillor will save you from me.’

‘Look under his arms,’ says Robert Cecil in reply, softly, as though he hopes no one else in the room will hear. ‘Give me an honest report of what you see.’

Now Nicholas understands. Cecil fears his son might have contracted the pestilence.

Kneeling before the boy, Nicholas gives him what he hopes will be taken as a carefree smile. ‘Tell me now, Master William, does your mother play Tickle with you?’ He flutters his fingers. The boy grins. Nicholas looks up at Lady Cecil. ‘Madam, will you assist me?’

Understanding him at once, she makes a fuss of the boy, pretending to pinch him on the side. He squirms away from his mother’s fingers, laughing loudly and throwing up both arms in delight. Cecil looks on intently. If he objects to the frivolity, he keeps it to himself.

Nicholas gently holds the boy’s arms aloft and studies the red patches that are clearly visible in the armpits. He knows at once what he’s looking at.

He remembers that when he had his practice on Bread Street – before Eleanor’s death; before the fall – his richer clients had taken a too-speedy diagnosis as a sign of sloppiness. They had wanted their money’s worth. But he can sense Robert and Elizabeth Cecil’s anxiety. There is no point in prolonging it. He stands up, finding himself stifling an unexpected yawn as the hour catches up with him.

‘An irritation of the skin, Sir Robert, Lady Cecil. Nothing more. These are not buboes.’

‘Thank our merciful Lord!’ Robert Cecil’s explosive release of breath is the first display of emotion Nicholas has witnessed since his arrival.

‘But there is more,’ says Elizabeth Cecil, restoring the child to her lap, where he starts toying with the edge of the cushion. ‘His sleep has also been much disturbed of late. He spits out his milk-sop. He mewls a great deal. And my ladies tell me he has a fever.’

To Nicholas’s ear, she sounds as if she’s testing him. He lays a hand on the boy’s forehead. It feels hot to the touch. He calls for a candle to be brought nearer, the better to see inside the child’s mouth. ‘You said he spits out his milk-sop. Does he swallow water with ease?’

Elizabeth Cecil looks at one of the ladies, who shakes her head.

‘Inflammation of the columellae,’ Nicholas says. ‘If you look, madam, you’ll see: there at the back of the throat.’

‘What do you prescribe?’ she asks.

‘If you wish a strictly non-heretical regime,’ he says, giving in to sarcasm and instantly regretting it, ‘I’d suggest a purge to empty his bowels, and wet-cupping to draw blood from the skin. Possibly a small incision made under the tongue to take out the over-hot blood. That’s what the textbooks would have me do.’

She smiles. ‘Perhaps I was a little too hasty earlier, Dr Shelby. But a mother is entitled to be protective, is she not?’

‘Of course, madam.’

‘So?’

‘For the soreness under his arms, a balm of milk-thistle and camomile. For the throat: a decoction of cypress leaves, rose petals, garlic and pomegranate buds, all in honey.’

Robert Cecil coughs, as if to remind them of his presence. ‘I’ll send a man to the apothecary on Spur Alley.’

‘Husband, it is not even dawn—’

‘What of it?’

‘May I make a suggestion, Sir Robert?’

‘Yes, of course, Dr Shelby.’

‘Let me have Mistress Merton make up the physic for you. I’d trust her ingredients over anything a member of the Grocers’ Guild puts in a pot. Half of it’s likely to be dried grass and crushed hazelnuts.’

‘Don’t tell me you’ve run afoul of the grocers as well, Dr Shelby,’ Robert Cecil says. ‘After the College of Physicians, the Barber-Surgeons, and the Worshipful Company of Tailors, is there any guild in London you haven’t upset?’

‘The vintners speak highly of me,’ says Nicholas in a flat voice devoid of frivolity.

‘Perhaps I’ve been mistaken in my opinion of you, Dr Shelby,’ says Elizabeth Cecil with a wry smile. ‘I ought to know by now that a pearl is not to be judged by its shell.’

The clear reference to her husband catches Nicholas off-guard. He has always assumed Lord Cobham’s daughter married the crook-backed Robert Cecil solely for the name. Until now, it had never dawned on him that love played any part in Cecil’s life.

As they walk back to Sir Robert’s study, Nicholas says, ‘When your men hammered on the door of my lodgings, I feared it was the parish, come to tell me that plague had crossed the river.’

Robert Cecil glances up at him pensively. ‘At present it seems confined mostly to the lanes around the Fleet bridge. One of Elizabeth’s ladies has family there. So naturally I assumed the worst. Let us hope to God it can be kept in check.’

‘The Lord Mayor has done the right thing, Sir Robert. As long as everyone keeps their dwelling clean and the street outside free of refuse—’

‘And what would be your heretical view of the cause of this contagion, Dr Shelby?’

A weary smile. ‘I know no better than any other physician, Sir Robert.’

‘Men who don’t think with the herd are often wiser than they know, Dr Shelby. Speculate.’

‘I know that casting horoscopes and wrapping yourself in ribbons inscribed with prayers has no discernible – and, more importantly, repeatable – effect, if that’s what you mean.’

‘But its transmission: have you no views of your own?’

‘It is held to move easily in tainted air, but how, and from where, I cannot say. Nor can I tell you why some who catch it die, while others live. That may have to do with age and constitution, but it is by no means certain. The disease is a mystery – an exceptionally malign mystery.’

‘Well, the Privy Council has done what it can. The infected houses are to be shut up and a watch set over them. We’ve forbidden all fairs and gatherings within the city. The rest is up to God.’

‘Then let us hope it dies of starvation, Sir Robert.’

‘Amen to that. At present there’s no talk of adjourning the Trinity term for Parliament. But if Her Majesty starts thinking of removing herself to Windsor or Greenwich, there will be a great leaving of this city, mark my words.’

Back in Cecil’s study, Nicholas reaches for the gabardine he’d left hanging on a chair. Through the window, a faint grey line marks the boundary between the fields of Covent Garden and the still-black sky.

‘Leave your coat a while longer,’ Robert Cecil says, fixing him with an uncompromising look. ‘I have something else to ask of you.’

Here it comes, Nicholas tells himself, his heart sinking. With Cecil, a summons is like the bark on a rotten tree: what is on the surface is not always what lies beneath. Peel away the layers and you’re likely to find black beetles crawling about underneath.

‘I want you to go on a journey for me.’

‘A journey, Sir Robert? What manner of journey?’

‘Quite a long one, as it happens. Are you familiar, by any chance, with the city of Marrakech?’

The courtier’s little bejewelled index finger traces a line on the globe’s lacquered surface, down the Narrow Sea towards Brittany, then across the Bay of Biscay, past Portugal, all the way to the African continent, almost to the point where knowledge ends. Here and there the fingertip ploughs through little flurries of waves, drawn simplistically as a child might draw the wings of a bird in flight. ‘Saltpetre, Dr Shelby,’ Cecil says as his finger runs southwards. ‘It is all about saltpetre.’

Nicholas looks at him blankly.

‘Let me explain. The Barbary Company was set up by Their Graces, Leicester and Warwick, to trade with the western nations of the Moor. We send Morocco fine English wool. In return, Sultan al-Mansur sends us spices and sugar.’ As his fingertip reaches the Barbary shore, Cecil’s eyes narrow. ‘But that is not the sole extent of our commerce, and I must have your word that you will not speak of what I am about to tell you beyond this room – on pain of severe penalty.’

Nicholas wonders if this is the point where he should stick his fingers in his ears – but he knows full well that not actually hearing one of Robert Cecil’s confidences is no protection at all. Reluctantly he nods his acceptance.

‘Until some fifteen years ago,’ Cecil continues, ‘Philip of Spain – and his Portuguese puppet Sebastian – were masters of Morocco. Then the Moors rose up and expelled them. Now we send Sultan al-Mansur new matchlock muskets, to defend his realm against their return.’

‘And in payment he sends us saltpetre,’ Nicholas guesses.

‘Which you, Dr Shelby, will know – from your service in the Low Countries – is a crucial component in the manufacture of gunpowder. Do you happen to know how many Spanish ships were sunk as a direct result of our gunfire, when Philip sent his Armada against us?’

‘Not off the top of my head, no.’

‘None,’ Cecil says archly. ‘Drake had to close with them at Gravelines before our cannon could do them proper harm. Moroccan saltpetre is amongst the finest there is. We need every ounce we can get, in order to ensure that if the Spanish snake comes against us again, we can out-charge his cannon.’

‘But that still doesn’t explain why you want me to go to the Barbary shore,’ Nicholas says.

‘I’m sure you will not be surprised to know that I maintain an agent in Marrakech, expressly to keep watch on our interests.’

It could scarcely surprise Nicholas less. The most isolated village in England knows the Cecils are the eyes and ears that ceaselessly protect England from her enemies. They have their people everywhere. Mothers warn their children that if they misbehave, the Cecils will see their faults almost as surely as God Himself.

‘The man I employ as my spy in Marrakech is a half-English, half-Portuguese trader named Adolfo Sykes,’ Cecil tells him. ‘He is the Barbary Company’s factor there. But in the past weeks three Barbary Company ships have returned to England without a single one of his customary dispatches. I fear some mischief has befallen him.’

‘But why send me? Yes, I know a little about wool – my father is a yeoman farmer – but I couldn’t tell saltpetre from pepper, if you put it on my mutton.’

Cecil gives him a condescending smile. ‘Because to send just another merchant would be as pointless as sending my pastry cook. I need an educated man, Dr Shelby – someone who can assume an envoy’s duties. If the Spanish have swayed the sultan against us, I want someone with the faculties to sway him back again.’

‘But I’m a physician, not a diplomat.’

‘Exactly. One of the sultan’s close advisors – a Moor named Sumayl al-Seddik – is benefactor to a hospital in the city. My father had dealings with him when he came here with the entourage of the sultan’s envoy some four years past. I’m sure you will recall the public tumult that accompanied the visit.’

‘Eleanor and I were in the crowd,’ Nicholas says, remembering. ‘That was before…’

A moment’s uncomfortable silence, until Cecil says, ‘Yes, well… you can tell Minister al-Seddik that you’ve come as an envoy to foster ties of learning between our two realms. That should pass well enough as a believable reason.’

‘An envoy who looks like a Thames waterman,’ Nicholas says, throwing Cecil’s earlier words back at him.

Sir Robert gives a diplomatic cough. ‘If that’s your only other objection, Dr Shelby, let me reassure you: I have more tailors than I do horses.’

Nicholas takes a steadying breath, so that his answer sounds appropriately resolute. Since the moment two years ago when he’d agreed to act as Cecil’s physician, in return for a stipend that would allow him to set up a charitable practice on Bankside, he has known this time would come. Hasn’t Bianca warned him enough times? Nicholas, sweet, Robert Cecil offers nothing without a reason. There is always a price to be paid in return.

He thinks of the last journey he undertook for the Lord Treasurer’s crook-backed son. It had ended with two slack-eyed killers dragging him towards the centre of London Bridge and the river waiting below, the pain of the beatings coursing through his limbs and howling in his ears. If it hadn’t been for Bianca’s courage that night, he wouldn’t be standing here now.

Yes, he thinks, a journey undertaken for Robert Cecil does not always end at the destination you are expecting.

3

In the shadow of the riverside church, St Saviour’s market is in full cry. Competition for a sale is fierce. Drapers loudly proclaim the quality of their ribbons; farmers in from the Surrey countryside boast you’ll find no better winter vegetables outside the queen’s own gardens; cutlers swear on their mother’s graves that their knives are newly forged and not pawned by destitute sailors laid off from the royal fleet. And weaving through the crowd, like pike in a shady pool, the cut-purses and coney-catchers hunt their prey.

Not that any of them would think for a moment of waylaying the comely young woman with the amber eyes who walks around the stalls with such an assured air, a wicker basket tucked under her arm, her waves of dark hair pinned beneath a simple linen coif. They’ve heard it said that if you try to slip your hand between bodice and kirtle to steal away her purse, you’ll wake up next morning with a raven’s claw instead of fingers. Bianca Merton is known to them. Bianca Merton is out of bounds.

And by association, so too is the curly-headed lad with dark eyes and skin the colour of orange-blossom honey who walks beside her.

Banksiders know Farzad Gul now, almost as well as they know his mistress. They greet him as if he were one of their own. After all, he is Bianca Merton’s Moor, and thus something of a curiosity. His colourful slanders of the Pope and the King of Spain, learned from the English mariners who rescued him from shipwreck, have made him as popular as any Southwark street entertainer.

Today Farzad is making one of his regular visits in search of vegetables for the Jackdaw’s pottage pot. Usually he would come alone, but with the wedding pending, Bianca has taken the opportunity to accompany him. She has the better eye for quality braids and ribbons with which to turn his battered jerkin into something a little more befitting a groomsman.

‘An English wedding might not be the match of a Paduan one, or a Persian one for that matter,’ she tells him sternly, when his interest in haberdashery fails at the second stall she drags him to, ‘but I will not abide you looking like a vagabond, young gentleman.’

‘No, Mistress,’ he says, with downcast eyes.

‘So then, you go and find us some of Master Brocklesbury’s cabbages, and I will see to the ribbons. Meet me by Jacob Henry’s oyster stall when you’re done.’

‘Yes, mistress,’ Farzad says with a grin, knowing the choice of rendezvous means a cup of the best oysters to be found this side of the river.

As he heads deeper into the market, alone, Farzad Gul wonders where he might be now, were it not for Mistress Bianca. It is two years since he found himself cast up in this strange city. If his rescuers had not happened to stop at the Jackdaw tavern on their paying-off, perhaps he might have sold his cooking skills to a new ship, sailed away again to some other strange place far beyond the world he had once known.

Every day Farzad wonders where his mother and the other survivors of his family are. In his mind he can trace their soul-crushing progress across the scorching desert wilderness, from Suakin on the Red Sea to a slave market in Algiers or Tripoli, or Fez, or even Marrakech. But from there they fade away entirely; sold, undoubtedly – if they lived; turned from the boisterously argumentative characters of his childhood into living ghosts.

But living where? Sometimes he prays they never made landfall at all, but followed his father and his sister into heaven.

A jarring blow to his shoulder pulls Farzad back into the present. He hears a contemptuous ‘Out of my way, heathen dog!’

Turning, he sees two lads of about his own age, dressed in the jerkins and caps of city apprentices. One has his hands in his belt and his elbows spread aggressively. ‘And take your filthy Blackamoor eyes off me,’ he snarls in an accent that, to Farzad, feels somehow familiar.

‘I am no heathen, I am from Persia,’ Farzad says pleasantly, refusing to rise to what is clearly a challenge. And to take the anger out of the air, he adds brightly, ‘And the Pope has the breath of an old camel!’

To his surprise, his words fail to bring about the expected slapping of thighs and jocund howls of approval. The lad with the elbows rushes at him, hurling Farzad back into a cheese stall. Round yellow truckles tumble onto the cobbles.

Southwark street-fights can swiftly run out of hand. Knives get drawn. Sometimes even swords. Deaths are not unknown. So the stall-holders at St Saviour’s are adept at putting them down before they get started. A burly weaver whom Farzad recognizes as a regular at the Jackdaw pins one of the apprentices in a vicious armlock.

‘That’s enough out of you, young master,’ he says, giving the lad’s arm a corrective wrench. ‘If you’ve a mind for a brawl, you’d be better off back home in Ireland, taking your anger out on the Spanish, if they try a landing. We’ll have none of your bog-trotting rowdiness here.’ He releases his grip, thinking the apprentice has learned his lesson.

But he hasn’t. He starts towards Farzad again, who is trying to put the cheeses back on the stall. ‘One day soon I shall be a prince over the likes of you,’ he snarls, his Irish accent thickened by his anger. He stares close into Farzad’s face. ‘We should permit none of your kind here. Our Captain Connell would know what to do with a Blackamoor like you.’

And lest there be any doubt about the sort of man this Captain Connell might be, he draws the blade of one hand across his own throat. Then he turns and walks away, beckoning his companion to follow.

Farzad watches them go, cold in his heart. Not at the insult – he’s borne much worse – but at the mention of an all-too-familiar name: Captain Connell. It is a name Farzad Gul has long prayed he would never hear again. It is the name of the cruellest man in the whole world.

‘Tell me again, Nicholas: where?’

It is later that day, in Bianca Merton’s apothecary’s shop on Dice Lane. She has assumed what Nicholas calls her tavern-mistress’s face – the one she adopts when a taproom brawl is about to kick off, someone exceeds his credit or a Puritan complains about the sinfulness of Bankside whilst asking directions to the Cardinal’s Hat, all in the same breath. Nicholas marvels at how her features can change from exquisite to terrifying in an instant.

‘Marrakech,’ he repeats with a slight trace of discomfort, handing her the list of medicines he has promised Robert and Elizabeth Cecil.

She keeps her eyes fixed on the distillations, powders and medicaments: sweet clover boiled in wine for Walter Pemmel’s sore eyes… saffron dissolved in the juice of honey-wort for Mistress Gilby’s leg ulcers…

‘It’s in Morocco,’ he says. ‘Sir Robert showed me – he has a terrestrial globe, with all the lands and capitals—’

‘I know where Marrakech is, Nicholas,’ she says, brushing aside a pennon of ebony hair that has fallen over one eye. ‘I was brought up in Padua and my father was a merchant, remember? I can name all the great cities of the known world, Christian or Moor.’ She looks up again and begins to count them off on her lithe fingers, ‘Venice, Aleppo, Lisbon, Constantinople, Jerusalem…’

‘You can stop. I take your point: you know where Marrakech is.’

‘Why does he want you to go there, of all places? If he wants spices, I know plenty of merchants on Galley Quay who import from Barbary.’

‘It’s about diplomacy,’ he says evasively.

‘Nicholas, you’re a physician, not a diplomat.’

He gives her the answer Robert Cecil proposed as a masquerade. ‘The Moors have a great tradition in medicine. Most of our medical texts were translated from Arabic versions of the Latin and Greek originals. He wants me to go there to discover what, if anything, we might learn from them.’

She fixes him with those unsettling amber eyes. ‘You cannot go to Marrakech, Nicholas. The wedding – remember?’

‘It doesn’t matter.’

‘What do you mean – it doesn’t matter?’

‘Because I’m not going. I told him No.’

The corners of Bianca’s mouth lift into an incredulous half-smile. ‘You refused Robert Cecil?’

‘I’m not his slave, Bianca. I’m his physician.’

She taps one of the pots on the table, as if she’s just checkmated him at chess. ‘He didn’t threaten to stop your stipend – force you to abandon your practice for the poor?’

‘No.’

‘Or threaten to have me hanged for a heretic?’

‘No.’

‘Because he’s tried that line before, when he’s wanted to coerce you.’

‘No.’

‘I suppose he swore on his mother’s grave there was no one else he could trust to do the job but Nicholas Shelby?’

‘Bianca, Robert Cecil has agents in more places than even you can name. I’m sure one of those will serve his needs more adequately than I. If he really must have a physician for the task, he can call on the College. Someone like Frowicke, or Beston. I’m sure they would be only too happy to spend three weeks at sea in a leaky ship full of rats and lice, so they can tell the descendants of the great Avicenna where they’re going wrong.’

‘Who?’

‘Ibn Sina. He was a Persian physician. We know him as Avicenna.’

She comes out from behind the table, the hem of her gown swirling around her ankles like a willow in a summer squall. ‘Well, I know that Robert Cecil is a snake. You have denied him – haven’t you?’

‘I told you, yes.’

She fixes him with a stern gaze and turns away before responding. ‘Good, because for a moment I was sure you’d invented the whole story simply in order to disappear for a while – to avoid the wedding.’

The Jackdaw has seldom looked so resplendent. Fresh paint gleams on the lintel. The ivy around the little latticed windows is neatly trimmed. The irregular timbers appear to be merely resting, rather than sagging under the three hundred years of travail they’ve endured, holding up the ancient brickwork. As Nicholas follows Bianca through the doorway, he catches the mingled tang of hops, wood-smoke and fresh rushes. From her place by the hearth, the Jackdaw’s dog, Buffle, looks up at their arrival, wags her tail once and promptly goes back to sleep.

It has not been easy for Bianca to stay away, now that she’s left the daily management of the tavern to Rose, her former maid, and to Ned Monkton. She suspects that if her apothecary shop was not doing such brisk business, she’d be poking her head over the threshold every other hour.

Almost immediately she spots Ned. He’s standing in the centre of the taproom, casting an appraising eye at the scattering of breakfasters like a fiery-bearded Celtic chieftain after a good battle. Seeing her, he smooths his apron over his great frame and attempts a gallant bending of the knee.

‘Mistress Bianca! ’Pon my troth, ’tis wondrous good to see you,’ he says. ‘Rose has the accounts ready, if you’ve come to see them. Just squiggles to me, but she assures me they’re in order.’

‘I’m sure they are, Ned,’ Bianca says, with more confidence than she feels. Trusting Rose to keep anything in order – especially from a distance – has not come easily to her.