Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Krimi

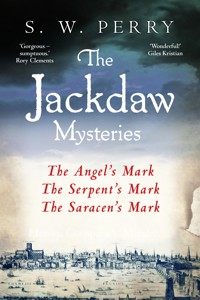

- Serie: The Jackdaw Mysteries

- Sprache: Englisch

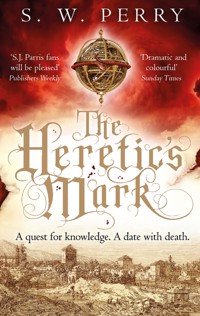

'Historical fiction at its most sumptuous' Rory Clements 'S. J. Parris fans will be pleased' Publishers Weekly ----------------------------------------------------- The quest for knowledge can lead down dangerous paths... London, 1594. The Queen's physician has been executed for treason, and conspiracy theories flood the streets. When Nicholas Shelby, unorthodox physician and unwilling associate of spymaster Robert Cecil, is accused of being part of the plot, he and his new wife Bianca must flee for their lives. With agents of the Crown on their tail, they make for Padua, following the ancient pilgrimage route, the Via Francigena. But the pursuing English aren't the only threat Nicholas and Bianca face. Hella, a strange and fervently religious young woman, has joined them on their journey. When the trio finally reach relative safety, they become embroiled in a radical and dangerous scheme to shatter the old world's limits of knowledge. But Hella's dire predictions of an impending apocalypse, and the brutal murder of a friend of Bianca's force them to wonder: who is this troublingly pious woman? And what does she want? Paise for S. W. Perry's Jackdaw Mysteries: 'Engaging' Sunday Times 'Beautiful writing' Giles Kristian 'Brilliantly evokes the colours, sights and sounds of the Elizabethan era' Goodreads review 'Gripping, packed with twists and turns!' Goodreads review 'Spellbinding . . . I fell in love with every character' Goodreads review READERS ARE ALL-IN ON THE HERETIC'S MARK 'Fabulous read' ***** 'Immersive reading experience' ***** 'Unputdownable' ***** 'The Elizabethan period is brought to life' ***** 'I love the mixture of history and fiction' *****

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 641

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Also by S. W. Perry

The Jackdaw Mysteries

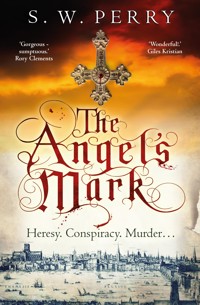

The Angel’s Mark

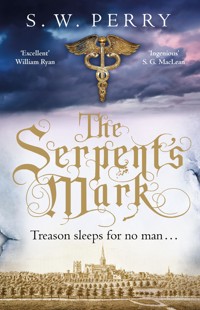

The Serpent’s Mark

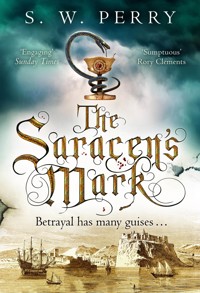

The Saracen’s Mark

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © S. W. Perry, 2021

The moral right of S. W. Perry to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 78649 903 5

E-book ISBN: 978 1 78649 902 8

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

For my family

When these prodigies do so conjointly meet,

let no men say ‘These are their reasons, they are natural’: For I believe they are portentous things…

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, JULIUS CAESAR

Prologue

The White Tower, London, 7th June 1594

They come for him shortly before dawn with a showy rattling of keys loud enough to wake the ghosts on Tower Hill. He rises stiffly from the first proper rest he has had in weeks, his joints reclaiming the pain the cold stone floor has borrowed while he was asleep. ‘Anon, anon!’ he protests as they take him by his chains. ‘All in good time. Incarceration is no friend to old bones.’

‘Old bones or young – it matters not,’ says his gaoler with the wistful familiarity of the prisoner’s confessor. ‘You’re wanted at Whitehall.’

‘Whitehall?’ he replies. ‘Has Her Grace the queen spoken for me? Does the Privy Council accept my innocence? Are they setting me free?’

But no answer comes as they hurry him down the wet, slime-covered steps towards the waiting wherry – only the sharp-tongued screeching of the gulls from the darkness of the river.

After months in captivity, Dr Roderigo Lopez has almost forgotten what it is to look out upon a horizon slowly prising itself from the grip of night. He stares about in cautious expectation. By the time they approach Westminster there is enough light for him to see, to his left, the pale mass of Lambeth Palace rising above the reeds. To his right, the grand houses along the Strand are taking shape. He knows them well. Within their private chambers he has administered to the greatest men in England. Powder of Spanish fly to help the Earl of Leicester in the bedchamber when his ardour failed to match his ambition; mercury to cure young Essex of the French gout; enemas to ease old Burghley’s fractiousness at the dinner table. The rewards had been handsome, if only to buy his silence: a good house, a certain prestige, money, even the queen herself for a patient. But they had never truly seen him as one of their kind. In his heart, Lopez had always known it.

At the Westminster stairs the boatmen hand him over to a brace of uniformed halberdiers in crested steel helmets. He almost laughs. Do they think a single white-haired old Jew might threaten the very realm itself? Do they not know that, after months of confinement, he can barely walk unaided?

In a panelled chamber with an embossed ceiling painted blue and studded with yellow plaster stars wait two members of the Queen’s Bench, Attorney General Coke and Chief Justice Popham. They are grave men in ermine-trimmed gowns. No smiles. Barely a greeting. They sit behind a table spread with expensive crimson cloth. It is bare, save for a leather-bound Bible and a roll of parchment with a tail of golden ribbon and a grand wax seal attached. Lopez notes the seal has been broken.

Let them think you’re the last man on earth to bear a grudge, he tells himself. They might find a little mercy in their cold hearts.

‘You’re up early, gentlemen,’ he says, smiling.

‘This is not a business for late sleepers,’ Coke says.

‘Have you brought Her Grace’s letter of pardon with you?’ Lopez asks, glancing at the parchment.

But their hard, formal faces tell him that whatever this document is, it does not carry his salvation. The pain in his joints, temporarily forgotten in the blossoming of hope, begins to scream at him again: Fool… fool for ever thinking they would find mercy in their hearts for a man like you.

With indecent haste, Coke and Popham put him through a perfunctory second trial, as though the first – it seems an age ago now – had somehow failed to stick, like the colour in a badly dyed shirt. A detestable traitor, they call him. Worse than Judas. There is no crime on earth more heinous than plotting to poison a monarch anointed by God. He was guilty of it in February, he is somehow even guiltier in June. And so he will hang by the neck until half-choked, suffer the severing of his privy organs and disembowelment by the knife – all while there is enough life left in him to appreciate the executioner’s skill at butchery. And if that doesn’t convince him of his perfidy, they will quarter his torso with an axe, burn the sundered parts and throw the ashes into the river. He will have no grave. Only his head will endure a strange immortality: set upon a spike on the southern gatehouse of London Bridge as a warning to future would-be regicides.

Why do I not fall to my knees in terror? he wonders. Perhaps it is because terror has become such a familiar companion during his lonely imprisonment. He knows it like an old friend. It cannot bite him any harder now.

Until they tell him it is to be today. At Tyburn.

There is an etiquette to an execution for high treason. Whether it be a solemn confession or a passionate protestation of innocence, an address to the mob is required. And the condemned man must stand naked as he prepares himself for the leaving of this world, just as he was when he came into it.

The executioner tears the dirty shirt from Dr Roderigo Lopez’s back. He turns the pale, trembling body to the crowd. Look, he seems to be saying, can you not see the stain of guilt on the puckered white flesh?

‘I love the queen as well as I love our Lord!’ Lopez cries out.

‘Papist traitor!’ someone shouts. Others pick up the chorus: ‘Vile Hebrew… Spanish assassin…’ This last insult hurts him more than the others. He is Portuguese, not Spanish. The Spanish are his enemy, as much as they are to the people now hurling their abuse and spittle at him.

As the executioner places the rough hemp noose around Lopez’s frail neck to begin the slow gruesome journey, the words of the man who lit the fire that sustains the queen’s religion – Martin Luther – echo in the physician’s lonely, tormented soul: Every man must do two things alone… his own believing, and his own dying.

In a different life, the man watching from the crowd had been someone of substance. But that was before his fall.

Grand in stature with a voice to match, he too is a physician – once the most renowned anatomist in England. There had been a time, Sir Fulke Vaesy recalls, when he had been a proconsul of the medical profession. A time when he could afford to attend an execution in silk-lined hose and imported Bruges shirts. He has shrunk a little since then. His reputation has gone, and with it the income. The manor house at Vauxhall has gone too, sold to some upstart warden of the Fishmongers’ Guild. The expensive brocade doublet he had worn on his imperious strolls down Knightrider Street to the College of Physicians is now patched and faded, like the covering of an old chair. He no longer has the spare cash to replace it. Now he is reduced to giving purges and drawing blood, like a country barber-surgeon.

Sir Fulke Vaesy knows exactly who is to blame for this ruination. Being a man who values careful accounting – at least when he had property and possessions to account for – he has drawn up a proper reckoning. It does not exist on paper. It cannot be presented as a bill. Nevertheless, the columns are neatly ordered in his head: every humiliation, every slight, every averted eye and unanswered greeting, every cancelled invitation… all assigned a price and entered in the ledger.

And where, now, is the fellow to whom this bill should be presented? In the pay of Sir Robert Cecil, that is where. Physician to Lord Burghley’s ill-formed younger son. Favoured by the queen herself, if what Vaesy has heard is true – though how Her Grace can bear to listen to the man’s wild, heretical ideas he cannot imagine. These undeserved endowments are, in Vaesy’s mind, the interest on the debt the wretch owes.

With detached professional interest, Vaesy observes the executioner take up his knife and geld the struggling old man on the scaffold. He nods at the practised ease with which the wrinkled white belly is opened up, spilling the hot pearlescent billows onto the planks. He watches the blood spill over the edge of the platform. For a moment he sees himself climbing the steps and instructing the crowd on the inner workings of the human body.

The axe begins to swing, quartering the Jew’s still-breathing body with a sound like someone dropping four heavy sacks of flour in quick succession. Then one final blow finishes the grisly masque for good. The executioner holds up the head by its now-crimson beard.

And in that moment the man watching from the crowd forgets the crush of sweating bodies that press upon him with such rude familiarity. The stink of unwashed common broadcloth and half-eaten coney pies, of cheap ale and rotten gums, fades entirely from his nostrils. In its place, as if carried sweetly on a sympathetic summer breeze, Sir Fulke Vaesy thinks he can smell the faint but distinct scent of revenge.

PART 1

Falling from Heaven

1

St Thomas’s Hospital, Southwark. Thirteen days later, 20th June 1594

‘Tell us, Dr Shelby: when did you first conspire with the executed traitor Lopez to poison Her Grace the queen?’

The questioner wears the livery of Robert Devereux, the young Earl of Essex. He is a large man. He has to stoop slightly in this dank low-ceilinged former monk’s cell. His face reminds Nicholas Shelby of an oval of badly cast glass on a grey day, cold and impenetrable. Judging by the foot-long poniard he wears at his belt, the noble earl has not hired him to wait at his table or tend his privet hedges. His companion is also armed. He stands close to his master, as though he hopes a little of the other man’s menace might rub off on him.

Even in summer the hospital warden’s office has the dank stink of the river about it, the walls cold and slippery to the touch, a place more suited to burial than the administration of healing. Now, in the shocked silence that follows the man’s accusation, it has for Nicholas the stillness of a freshly opened crypt. Before he can reply, the warden gives a frightened little harrumph. His eyes, set unnaturally close to the bridge of his thin nose, hurriedly fall to the ledgers on his desk. He seems to think that the harder he studies the inky scrawls, the further he can remove himself from the implications of what he’s just heard. ‘I have no knowledge of Mr Shelby,’ he mutters to the pages, ‘other than of his duties at this hospital. Beyond that, I am not of his acquaintance.’

Nicholas thinks: that’s exactly the kind of betrayal I might have expected from a man I have always imagined more as a pensioned-off Bankside rat-catcher than a hospital warden, a man who sneeringly refuses to understand why a physician who now serves Sir Robert Cecil, the queen’s privy councillor and secretary, should still care enough about healing to visit St Thomas’s Hospital for the sick poor of Bankside on a Tuesday and Thursday, without even asking for the shilling a session you grudgingly paid me when I was down on my luck.

He keeps his reply calm and measured. Bravado will be as incriminating as hesitancy. ‘Who are you to speak with such impertinence to a loyal and obedient subject of Her Majesty?’

The man gives a smile that is very nearly a sneer. ‘Judging by what Master Warden has just said, it would appear you must account for yourself without an advocate, Master Shelby. Please answer the question I put to you.’

‘It is not a question,’ says Nicholas. ‘It has no merit. It is an insult. And as a member of the College of Physicians, to you I am Mister Shelby.’

A contemplative nod, while the man considers if this has any bearing on the matter at hand. Then he looks at Nicholas with eyes as sharp as the poniard he carries at his belt. ‘Then as a physician, Mister Shelby, you must know what hot iron can do to a man’s fingers. How will you practise your physic with burnt stumps?’

‘This is risible. I will hear no more of it.’

Nicholas moves towards the door, intending to leave. A thick, leather-sleeved arm blocks his way. Not suddenly, but smoothly – as if the body it is attached to has seen all this before and knows precisely how this measure is danced.

‘Did you not see the recent revels at Tyburn, Mr Shelby?’ asks the younger of Essex’s men, a hollow-cheeked fellow with lank pale hair that hangs down each side of his face like torn linen snagged on a thicket. He mimics the lolling head of a hanged man, while one fist makes an upwards-slicing motion over his own ample belly. He dances a few steps in feigned discomfort, as though he’s stepping over his own entrails.

As ever when Nicholas is raised to a temper, which is not often, the Suffolk burr in his voice becomes more evident. ‘No, I did not! Let me pass. I have borne quite enough of this nonsense.’

‘That is a pity, Dr Shelby,’ says the owner of the arm. ‘It might have proved an instructive lesson – for your likely future.’

Nicholas bites back the reply that has already formed in his mind: What you call a revel was nothing but the murder of an innocent old man. In these present times, to express sympathy for a condemned traitor is almost as dangerous as committing the alleged treachery yourself.

‘You would be advised to give a proper account of yourself to Master Winter here,’ says the mimic with the lank hair, nodding towards his friend. ‘When did the executed traitor Lopez seek to enrol you in his vile conspiracy?’

‘Do you really expect me to answer that?’

The warden seems to deflate into an even smaller huddle over his ledgers. He shakes his head as if trying to cast off a bad memory, or perhaps to show Essex’s men that he never wanted Nicholas Shelby anywhere near St Tom’s in the first place, however far he may have risen since.

The one named Winter says, ‘Oh, be assured, sir, you will answer the denouncement – before me, or before the Queen’s Bench: the choice is yours.’

Denouncement. So that’s it, Nicholas thinks. Someone has made a false accusation against me. He tries to think who it might be. He has few enemies, and none made willingly. Perhaps some minor member of the aristocracy has taken offence that the new physician to Sir Robert Cecil refuses to purge him for an overindulgence of goose and sirloin.

‘Who has laid this false charge against me?’ he demands to know.

Winter’s reply is non-committal. ‘I am a servant of His Grace the earl, not a market-stall gossip.’

‘And I am in the service of Sir Robert Cecil,’ Nicholas reminds him. ‘I am physician to his son. Now let me go about my lawful business.’

Winter puts one thick hand on the hilt of his poniard and lifts just enough blade from the sheath to show he means business.

‘I am sure Sir Robert can find another doctor to attend his son, should the present one lose his life resisting arrest for treason. You are to come with us to Essex House.’

Nicholas has a sense of falling – the warning the stomach gives the brain of coming terror. He remembers that old Dr Lopez made a similar journey not so many months ago, and from there to the Tower. As he follows Winter and his boy out of the dank little cell and into the June sunshine the warden’s head does not lift from his ledger, as though Nicholas Shelby has been already condemned and forgotten.

In her apothecary’s shop on Bankside’s Dice Lane, Bianca Merton is preparing an emulsion for Widow Hoby’s inflamed ear. She takes up a bottle of oil of Benjamin and pours a generous measure into a stone mortar, which she sets on a tripod over the stub of a fat tallow candle. Then she breaks up some mint, marjoram and oregano, pares a few leaves of wormwood from a stem and drops the mixture into the gently warming liquid. As she begins to grind the pestle, the scents spill out in profusion. She inhales. She smiles. There might be an open sewer outside, but in her modest premises the air is always exotically fragrant.

Some who live in the teeming warren of lanes that cluster around the Rose playhouse on the south bank of the Thames would think it a shame to pour such a fine oil into the ear of an old woman with barely the clothes on her back to her name, but Bianca knows Widow Hoby has a good soul. Her husband was one of the more than ten thousand Londoners who were carried off by the pestilence that ravaged the city last year. She deserves a little luxury.

On Bankside, indeed throughout Southwark, there is a certain air of mystery – not to say notoriety – about Bianca Merton. For a start, she looks different. Her skin has a healthy caramel sheen to it, a hint (or so her mother always told her) of a family line that ran from the Italian Veneto across the Adriatic to Ragusa, and from there into Egypt, or Ethiopia, or even far Cathay. (Her mother had never been entirely specific on the subject.) But it is more than just her complexion – which admittedly has paled a little under the unpredictable English sun – or her startling amber eyes and the thick, dark convolutions that spill from a high, determined brow that mark her out as exotic. Whether her customers come for oil of bitter almonds to ease a ringing in the ears, a decoction of plantain, sorrel and lettuce for a nosebleed or simply for a chat, they cannot help but wonder if the rumours are really true: that the daughter of an English spice merchant and an Italian mother can mix a poison as deftly as she can a cure.

Being what the rest of London refers to disparagingly as denizens of ‘the Turkish Shore’ and thus used to the unusual, these same Banksiders have long since taken to Bianca Merton. Southwark admires a certain dash, a measure of what it likes to call ‘assurance’. Man or woman, poor or poorer (there are few enough in the city’s southernmost ward who are rich), they don’t much care if it’s not shown by their clothes. A jaunty cap worn at a rakish angle, a flash of bright ribbon, a string of polished oyster shells sewn to the collar in place of pearls will do, if it’s all one can afford. What is important is that you walk down Bermondsey Street or along the riverbank with your chin up, as though the Bishop of London, the queen’s Privy Council, the Lord Mayor and his Corporation – along with all their petty laws – can go straight to the Devil in a night-soil waggon, for all you care. And in this, Bianca Merton suits them down to the ground.

For those who have learned of it, and Bianca has done her utmost to ensure there are few, the only thing that might raise a doubting eyebrow is her faith. In a realm whose present queen is still under a pope’s sentence of excommunication, and whose former sovereign, the bloody Mary, burned three hundred Protestant martyrs before her own departure into a richly deserved hell, Bianca Merton’s Catholicism could well be viewed with suspicion. Not so much now, of course. Not since she purchased the Jackdaw tavern with the money her father had left her. There are few heresies a Banksider won’t forgive, if the price of his ale is competitive. And besides, you’d be hard pressed to find one who doesn’t have something in their larder they’d rather not share with the world across London Bridge.

The one thing they are all agreed upon is that they cannot quite bring themselves to address this comely young woman with the interesting past by her new, married name. She came to them as Mistress Merton, and Mistress Merton is how they see her still, regardless of their happiness at the match. Goodwife Shelby just doesn’t seem to fit.

When the oil infusion is complete, Bianca adds it to the rest of the medicines she has prepared for tomorrow’s early customers. She locks her shop and goes out into the warm summer air. She walks the short distance to the pleasant lodging she and Nicholas rent close to the river by the Paris Garden. On the way she passes the place where her Jackdaw tavern had stood for centuries – until that summer night last year, when the trail of mayhem caused by her new husband’s association with Sir Robert Cecil brought about its incineration and her own close brush with death. Recovering in the splendour of Nonsuch Palace, the home of Nicholas’s friend, John Lumley, she had often wondered how she would feel when she looked again on the ruins of the place she’d bought with her father’s inheritance when she arrived in London from her former life in Padua. She had suspected it would break her heart, despite the fact that Nicholas, after his return from the Barbary shore, had the means to rebuild it. To her surprise, she had dismissed the blackened skeleton with a shrug. New starts, she had realized, were nothing new to her now. They were to be embraced, not feared.

She stops to inspect the work. She observes the freshly hewn oak posts set into the scorched foundations, the frame upon which the new Jackdaw will rise, and checks that the masons have run the first few courses of bricks straight. Not too straight, mind; the Jackdaw was never about symmetry – that had been part of its charm. Announcing her satisfaction to the foreman in charge of the reconstruction, she walks on towards the Paris Garden.

Arriving at the lodging, she finds two notes left for her. The first is from Nicholas himself – their love is still fresh enough to leave each other billets-doux. She reads it, learns that he expects to return from St Tom’s by five and tucks it into the neckline of her gown, where she imagines the feel of it against her skin is instead of the warmth of his touch.

The second note is from Rose Monkton.

Mistress Moonbeam, as Bianca is wont to call her friend and former maid, has returned to Bankside to help her while the Jackdaw is being rebuilt. The note informs her that Rose has gone across the bridge, on an errand to visit an importer of spices on Petty Wales whom Bianca knows to be that rarity amongst Thameside merchants: an honest man. Too many of them these days are not above bulking out their wares with powdered acorns and other counterfeit dusts. This one does regular business with his counterparts in Venice, the middlemen in the trade from the Levant and Asia. It is a useful conduit for Bianca’s letters to her cousin in Padua, Bruno Barrani. All it costs is her continued custom, and free medicine for the merchant’s hermicrania. She checks to see if Rose has taken her latest letter with her, because Rose is liable to forget her own name if the wind changes direction suddenly. She has.

There has been a lot to tell Bruno since last she wrote – most of it impossible to put in a letter. So Bianca had confined herself to a report of daily life on Bankside, and for his greater interest – because Bruno likes to hear of strange phenomena – she had mentioned the mercifully brief fresh outbreak of plague in the spring; the great storm at the end of March that had torn up so many trees and ripped off so many roofs; and the fearful rains and gales of early April. Her final words, before closing with the usual expression of familial devotion and commending Bruno to God’s merciful protection, had touched on the matter closest of all to her heart: as yet, no sign of our hoped-for bounty…

That had been harder to write than she had expected. But the fact remains that, despite lying with Nicholas that night of the fire, and on many joyous occasions since, her belly is still as flat as it has ever been.

As Bianca sits in the window seat of the parlour, looking out across the unusually quiet lane to the close-packed timbered houses and the spire of St Saviour’s beyond, she hears the church bell ring four times. The slow, deliberate chimes remind her how time seems to be passing ever more swiftly. She has already seen the back of thirty. Only God knows how many years she has been allotted. As each one ends, so the possibility of bearing a child – their child – diminishes. To give Nicholas a healthy child would be the final laying of his first wife’s ghost.

To fill the time while she waits for him to return from St Tom’s, Bianca picks up a printed sheet purchased a few days ago from a bookshop near St Paul’s. It is the new poem by Master Shakespeare. She had been lucky to find a copy. They are flying out of the stationers’ faster than the presses can run them off. She lets her eyes skim over the words to get a feel for the piece, before reading it more attentively.

She does not get beyond the second verse before a dark and uncomfortable sense of foreboding comes over her, no doubt brought about by remembering what she has left out of her letter to her cousin:

O comfort-killing Night… Black stage for tragedies and murders fell…

Whispering conspirator with close-tongu’d treason…

Make war against proportion’d course of time.

Returning from delivering Mistress Bianca’s letter into the hands of the merchant on Petty Wales, Rose Monkton hurries south across London Bridge. She prefers not to linger in the narrow parts where it runs beneath the buildings that perch upon it as if they are teetering on the edge of a precipice. The crowd squeezes in so tight that you have to fight your way through the shoppers, the hawkers and the cut-purses. She prefers the few open spaces where there is a chance to look at the river sweeping beneath the great stone piers on which the whole implausible edifice is built. Then she can breathe properly. Then she can gaze east towards the Tower, or west towards the grand houses lining the northern bank around Westminster.

Rose has grown accustomed to grand houses recently. She’s developed a taste for them. Born in the narrow maze of lanes between the Paris Garden and Long Southwark in the shadow of the playhouse whose name she shares, she has always found the crush of the timber-framed tenements oddly reassuring, as comforting as the wooden walls of a cradle to a swaddled infant. But then, in the aftermath of the fire, and with plague still rampant in London, Master Nicholas had accepted Lord Lumley’s offer of sanctuary at Nonsuch Palace. True, she and her husband Ned dwelt in the servants’ quarters, but even they were grander than their former rooms at the Jackdaw.

The thought of Nonsuch makes her hanker for the comforting vastness of Ned’s huge frame. She will have to wait a little longer, she thinks with a resigned smile; Mistress Bianca still has need of her. A body can’t run an apothecary shop that tends to the needs of half of Bankside and watch over the rebuilding of a tavern by herself – not with the way that London day-labourers are wont to behave. And Bianca Merton is, after all, more an older sister to her than a mistress.

As she emerges from beneath the bridge gatehouse into Long Southwark, Rose takes care not to glance up at the traitors’ heads crowning the parapet like a macabre grinning diadem. She presumes the one unburnt relic of poor Dr Lopez is up there now, blackening in the summer sunshine.

She has heard Master Nicholas tell how he doesn’t believe the old man was guilty of trying to poison the queen. And to her mind it seemed a monstrous way to treat a physician. The barber-surgeon who pulled that diseased tooth of hers when she was eleven, perhaps. But not a doctor.

As she leaves the gatehouse and turns right towards the Pepper Lane water-stairs, eyes fixed straight ahead in an effort to resist the uncomfortable urge to look back and up over her shoulder, Rose sees a familiar figure coming towards her from the direction of Long Southwark.

He’s the last man you’d take for a physician, she thinks. She imagines men of medicine – like magistrates, priests and schoolmasters – to possess a stern gloominess brought on by all that book-learning, probably tall and lugubrious, and definitely old. Master Nicholas is none of these. How could he be? He’d never have won the heart of Mistress Bianca if he was.

He looks exactly what he told her he was before he became a doctor: the younger son of a yeoman farmer. Thus, being of a romantic mind, Rose imagines him made out of the same solid earth that sprouted the men who fought with the fifth Harry at Agincourt, or who now captain the ships of Drake, Hawkins and Raleigh. He looks as though he’d be more at home wielding a scythe than a scalpel, though she suspects he’d do it with the same careful diligence, allowing himself just the occasional flourish to show that he’s not all earnest sobriety, that he can laugh at himself, when required.

He’s wearing that old white canvas doublet of his, the one he came to them in, a twenty-eight-year-old foundling abandoned by the river he’d thrown himself into to escape his grief. It had taken her ages to clean the mud off it, while Mistress Bianca tended his battered body upstairs in the attic of the Jackdaw. He looks a lot different now, of course. He has the grateful eyes of a man who knows the value of a second chance. Now, even his coarse black hair and his tightly cropped beard know better than to sprout piratically, as Rose herself would prefer. But Mistress Bianca won’t have him looking like a felon, and has told him so more than once.

But who are these two fellows with him? She hasn’t seen them before. Not as big as her Ned, but large enough. And by the way they crowd him, they do not appear to be friends.

Rose becomes certain something is amiss when Master Nicholas does not smile at her. In fact he stares straight through her, save for a very brief shake of his head, as though he’s trying to tell her not to acknowledge him. Keeping her eyes off his, she waits until she feels it is safe to look back. She watches in horror as they bundle him down into a waiting wherry as if he’s the most wanted criminal in all London. In indecent haste the wherry pushes off into the current.

But not before Rose has had the opportunity to spot the embroidered design on the leather tunics of the two men. It is a mark she has seen before, when the young man whose livery it is made one of his many vainglorious processions through the city, graciously accepting with a wave of his gloved hand the hosannas of the admiring crowd.

2

The Strand, London. Later the same day

Essex House stands on the north bank of the Thames, between the Middle Temple and the eastern end of Whitehall. Like many of the great houses that line the river to the west of Temple Bar, it once belonged to a bishop. But that was before the queen’s father, the eighth Henry, decided he preferred his men of God – if not their monarchs – frugal. It has a grand banqueting hall, more bedrooms than the city has wards, and fine gardens that sweep down to the water’s edge, where two private water-stairs jut out like serpents’ tongues tasting the air for treason.

All London knows Essex House wears two faces. The first is cultured and fashionable. Poets and musicians come here, lavish masques are held amid the topiary. The dancing is exquisite. As are the boys who serve the wine.

The other face is darker. Like its equivalent, Cecil House, home of that other great faction of England, it is a centre of intrigue and politics, of foreign entanglements and alliances that shift forever like quicksand. Hidden away in places where a guest is unlikely to stray are the expert cryptographers, forgers, intelligencers. A few of these men are also practised in the application of a skill that would turn the stomachs of the more rarefied visitors who come in via the front gate. Their domain lies below ground – so the screams won’t disturb the neighbours.

Nicholas arrives by the water-stairs that serves this other face. As the wherry rocks against the piles, Winter gives him a helping shove that will leave bruises on his back for days. He almost falls at the feet of two other men waiting for him on the planks. They are middle-aged, of middle height and from the Middle Temple, judging by their dark legal gowns. Ominous, thinks Nicholas with mounting alarm. If they are Essex House lawyers, they may have been sent simply to intimidate. But if the noble earl has brought them in from the Temple, then the accusation may already be public knowledge. It could have gathered a momentum that will be hard to stop. It could be that the letters of his arraignment have already been prepared.

They lead him up the gently sloping gardens towards the great house. He sees gardeners in linen smocks trimming the topiary; clerks and messengers moving purposefully along gravelled pathways; a gaggle of expensively dressed young gentlemen practising archery, their arrows speeding deep into a straw target set against a shady elm tree, honing their skills in the hope the earl will take them on his next expedition to the Low Countries. Or Lisbon. Or wherever else glory and riches may be had, by those with an appetite for risk.

Looking back, he sees Winter and Lank-hair trailing him like a pair of wolves trying to anticipate which way their prey will break. In the distance, out on the river, two tilt-boats glide past incongruously, their passengers enjoying a pleasant picnic beneath the awnings.

The lawyers seem to be the only two of their profession in all London disinclined to speak. In silence they lead him towards an area of stables and storerooms. It is shady here. Nicholas feels a chill in his blood, though whether real or imagined he’s not sure.

They stop before a low lintel that caps a door studded with iron. One of the lawyers produces a heavy key from the folds of his gown. He inserts it into the lock-plate and tries to turn it. The lock does not yield. He tries again. And when that too is unsuccessful, a third time.

‘Are you sure this is the place?’ he asks his companion.

‘The old carpenter’s store – that is what His Grace’s secretary told me, Master Rathlin,’ the other replies.

Rathlin tries the key a fourth time. Withdrawing it, he stares at the intricate metal maze of the bit, until Winter steps forward, takes it from him, puts it in the lock and calmly turns it in the opposite direction. Nicholas stifles a grin. They can’t believe me to be that much of a threat, he decides. They clearly didn’t think it worth sending their best legal minds.

Inside, the chamber smells of wood-shavings and old animal pelts. It is bare, save for a furrowed carpenter’s trestle. Here and there little curls of paper-thin shavings poke through the dust like wavelets on a frozen pond. It looks as though it was last used when the Earl of Leicester owned the place, and he’s been dead almost six years.

‘They said there would be chairs,’ says Rathlin, as Lank-hair wipes the dust off the trestle with his forearm. ‘Why are there no chairs?’

Lank-hair is dispatched and returns a few moments later carrying a bench just big enough to seat two. He places it before the trestle with elaborate care, as though this were the Star Chamber and not an outhouse. The lawyer without the key gives a petulant little tut, motioning to the other side of the trestle. ‘We’re questioning the accused, not the wall,’ he mutters under his breath, a small triumph of petty revenge.

‘I beg pardon, Master Athy,’ mutters Winter, as though Lank-hair is not to be trusted to make his own apology.

This inept confusion gives Nicholas no comfort. It is not Rathlin and Athy who will pass sentence upon him. That will be left to Chief Justice Popham and Attorney General Coke. Not that it matters much. No matter how sound the accused’s protestations of innocence, treason trials tend to have only one outcome.

With Winter and his friend stationed behind him, blocking the exit, Nicholas stands before this mockery of the Queen’s Bench, trying to look as though he’s being kept from more important business. Rathlin, apparently the more senior man, looks around the mean little chamber, gives a sigh of resignation and begins.

‘You are Dr Nicholas Shelby, of Barnthorpe in the country of Sussex, accredited to practise physic by the Bishop of London, and a member of the College of Physicians. Is that correct?’

‘No,’ Nicholas says, sucking in his cheeks. ‘I’m Richard Tarlton.’

This causes Rathlin to look at Winter with a severe furrowing of the brow. ‘What’s this, Master Winter? Have you brought us the wrong fellow?’

Athy put his hand over his mouth and gives a lawyer’s sonorous cough.

‘Richard Tarlton was a comedic actor, Master Rathlin – at the playhouses. He’s dead.’

Rathlin looks surprised. ‘Oh, a jest.’ Then, disapprovingly, to Athy, ‘The playhouses, you say?’

‘I do, Master Rathlin.’

Rathlin studies Nicholas through narrowed eyes. ‘Sinful places, playhouses. Given over to those who rejoice in lust, and impertinence towards their betters.’

Nicholas sighs inwardly. That’s all I need: a lawyer and a Puritan.

‘It is alleged, Master Shelby,’ Rathlin continues, ‘that you were an accomplice in the recent vile conspiracy made by the Jew Lopez, a native of Portugal given shelter in this realm, to administer to our sovereign lady, Elizabeth, a concoction fatal to Her Highness. This plan was thwarted only by the diligence of her Privy Council and the intercession of the Almighty. What say you – guilty?’

‘I say the Trinity term must be a barren one for you lawyers, if you have time to waste on such a wild fabrication.’

‘The allegation came from a reliable source,’ says Rathlin.

‘Did it really? Would you care to name it?’

‘You think perhaps we have fabricated this charge on a whim?’

The evasion gives Nicholas a glimmer of comfort. An anonymous denunciation, he thinks. ‘I’d put my money on it coming from someone I refused to purge for a bellyache brought on by overindulgence,’ he says. ‘Prove me wrong.’

Athy looks down his nose at the accused. ‘This is not a trivial matter, Mr Shelby. We are speaking here of treason.’

Nicholas shrugs, a gesture that carries more indifference than he feels. ‘I get more than a few of such charges, now that I am in the service of’ – a pause to make sure they are paying attention, then a slowing of the voice as he plays the only card he holds – ‘Sir Robert Cecil, Her Grace’s secretary.’

But Temple lawyers are not so easily distracted. Rathlin says, ‘But you have oftentimes been in close proximity to Her Highness’s person, have you not?’

‘Oftentimes? No; I’m not her personal physician. Not yet.’

Nicholas remembers Robert Cecil’s warning last year when he returned from Morocco. The queen had expressed an interest in having him speak to her of the Barbary shore and how the Moors practised their physic. ‘Don’t get your hopes up,’ Cecil had warned him. ‘She makes invitations like that to every young man whose appearance pleases her.’ But Cecil had been wrong. Elizabeth had summoned him: once to Windsor, once to Whitehall and twice more to Nonsuch. The memory of their first conversation springs into his mind now. ‘Are you sure you are a physician, sirrah? You do not have an academic look to you.’

He’d taken it as a compliment.

‘Master Baronsdale tells me he considers you a heretic,’ he hears the queen saying, her white cerused face – almost as unmoving as a mask in a morality tale – creasing slightly with amusement at the expression on the faces of the assembled courtiers who are wondering what manner of fellow she’d commanded to appear before her. ‘In matters of physic, I mean.’

‘It is the privilege of the president of the College of Physicians to judge us humbler doctors as he chooses, Majesty,’ he had replied, head down out of deference. But to his horror that had enabled him to see that he was wearing an old patched pair of woollen hose. In the pre-dawn darkness when he’d dressed, Bianca had been half-asleep. Kissing him goodbye had taken preference over ensuring he’d been properly attired to meet his monarch.

Rathlin’s voice pulls him back to the present.

‘Nevertheless, you have been granted privy access to Her Grace’s chamber. We presume she did not call upon you to have you read poetry to her. What did you do there?’

‘We spoke of how the Moors of Barbary organize their hospitals. She was interested.’

‘The Moors have hospitals?’ asks Athy, as though the possibility has only just occurred to him.

‘For longer than we have had them. The one I visited was better than St Tom’s. Certainly cleaner.’

‘How remarkable.’

‘Not really. Many of our procedures come from Moorish physicians of old, or from the books of antiquity they saved from destruction by the barbarians.’

Rathlin asks, ‘And during these visits to Her Majesty, did you administer any foreign substance to her body?’

‘No.’

‘Nothing at all?’

‘I think I might have remembered. So might she.’

‘Did the traitor Lopez suggest such a thing to you?’ This from Athy.

‘Of course he didn’t.’

‘But he was present.’

‘Only at the first summons. After that, he was elsewhere – latterly in the Tower. I see you are not taking notes.’

‘This is a preliminary interview, Dr Shelby,’ Rathlin says. ‘There will be time enough for testimony later – when you appear before the Queen’s Bench.’

‘Were you ever alone with Her Grace?’ Athy asks.

‘Is that an offence? I hear tell the Earl of Essex is often in her privy company.’

‘Answer the question,’ says Athy sourly.

‘Then, never. I was always in the company of either Baronsdale or Beston.’

Rathlin raises a lawyer’s eyebrow, as though he’s found the fatal flaw in the defence. ‘So there were others in this conspiracy?’

Nicholas manages not to laugh. ‘Master Baronsdale is president of the College of Physicians. Beston is one of the Censors, responsible for testing our professional knowledge. Are you suggesting the entire membership of the College conspired to poison the queen, Master Rathlin? All of us?’

‘You could still have secreted your poison in some innocent-looking vessel, Dr Shelby.’

Now the laugh cannot be restrained. ‘Master Athy, Censor Beston might not be the sharpest of scalpels I’ve come across, but even he would manage to make a connection between a junior physician administering an unapproved draught to Her Grace and her subsequent demise.’

Rathlin leans forward across the trestle, the elbows of his lawyer’s gown leaving a snail’s trail of dust as they move. He steeples his fingers under his chin as he looks up at Nicholas with his cold judicial eyes. ‘Perhaps, being a medical man and not of our profession, Dr Shelby, you do not know that even speaking of the queen’s death is tantamount to sedition. It is forbidden.’

‘If you’re going to accuse me of seeking to poison her, and I am to defend myself, it’s a little difficult not to.’

‘Are you saying you deny the charge?’

For a moment Nicholas does not answer. Wearily he raises his gaze towards the low ceiling. Inches above his head a row of rusty iron hooks hang from a rafter like the sagging eyes of a dropsy patient.

‘Is that what you did to poor Dr Lopez – decide he was guilty from the start?’

Rathlin seems caught by surprise. ‘I cannot tell you, Dr Shelby,’ he says. ‘Neither I nor Master Athy was party to the examination of Lopez. That was conducted by the earl himself, and Sir Robert Cecil.’

The news gives Nicholas a glimmer of hope. Perhaps a formal charge has not yet been laid against him. Perhaps this really is a consequence of nothing but malice – a fiction uttered carelessly by someone who bears him a grudge. But even if it is, Nicholas knows this can still end in a lethal outcome. After all, the queen herself had not agreed to Lopez’s execution until the worm of doubt had been woken in her. What if the Earl of Essex is at this very moment in her company, reassuring her that another conspirator has been caught before he can strike? Poor Lopez had been her personal physician for more than thirteen years before she abandoned him. What hope could there be that she would lift even a single bejewelled finger to protect a young man who had been in her presence just four times, a man whom she had already called – perhaps only half-jokingly – a heretic?

Equally concerning to him is how far Robert Cecil will go to protect him. Lord Burghley’s son does little that is not in defence of his queen. For all the service Nicholas has given him over the past four years – service that has put his life in jeopardy more than once – he knows that in that crooked little body is an iron-willed ruthlessness. After all, Lopez himself was once Robert Cecil’s man. And look where that got him.

‘Master Winter,’ he hears Rathlin say in a voice he might well use when closing a prosecution, ‘I think it time to convey the accused to a place where he may be confined while he considers the wisdom of his defiance.’

And as he senses Winter and Lank-hair move to grip his arms, Nicholas Shelby understands that his ordeal has only just begun.

3

As evening approaches, Bianca Merton waits at the Falcon stairs for a wherry to take her across the Thames. The warmth of the day is fading; a chill is settling on the city. After half an hour her feet are tapping out a tattoo on the planks while the river mocks her impatience with dancing waves turned orange by the setting sun. Then three tilt-boats arrive from the northern bank almost simultaneously. A spirited but good-natured jostle with feet and oars breaks out amongst the boatmen for the best mooring post. ‘What are you doing on the water, Tom Frear? You’d be safer pushing a plough,’ shouts the first. ‘Mercy, good sirs,’ says the second to the passengers in another boat, ‘you’re the first lot today that Jack Tomblin ain’t managed to drown.’ Tomblin, not to be outdone, roars with good-natured scorn, ‘Make way for a proper waterman, you lubbers! Neptune hisself would weep to see such clumsiness.’

By custom, Bianca Merton would watch this tussle with mild amusement. But this evening she is desperate for the wherries to empty. She knows from experience how hard it is to get a private audience with Sir Robert Cecil.

Five young gentlemen from Gray’s Inn are the first ashore: trainee lawyers looking for diversion from their studies. To Bianca they look ridiculously young to be chancing purse and body on Bankside. Their beards are meagre and they have more pimples than a freshly plucked goose. She wishes the Jackdaw was still open. At least she’d be able to keep an eye on them, tell them which dice-dens and bawdy-houses to steer clear of, which alleyways to avoid if they should end up alone. But this evening it is all she can do to stop herself shouting at them to get out of her way. When the boat she has chosen is empty, she calls down to the waterman, ‘Good morrow, Master Frear. Will you take a fare to the Savoy hospital stairs?’

The boatman looks up. ‘You, Mistress Merton? The Savoy hospital? Nothing amiss, is there?’

‘Nothing amiss, Master Frear,’ she lies. He’s noted the agitation in me, she thinks. She tries to compose her features. ‘I have some business at Covent Garden, that’s all.’

‘Shall I wait for a full load to take upriver, or are you in a hurry?’

‘A hurry, Master Frear – if that’s not a burden to you.’

‘Then you’re in luck, Mistress. The tide’s still on the flow.’

Bianca does the best she can to settle on the cross-bench. Realizing her left hand is drumming on the plank, she fumbles inside her gown for her purse.

Leaning into his oars without breaking rhythm, wherryman Frear shakes his head. ‘There’ll be no need of that, Mistress Merton. You and Dr Shelby cured my Mags of the tertian fever. Twelfth Night last, it was. Say the word an’ I’ll row you to Oxford and back, an’ twice on Accession Day, all for gratis.’

Bianca gives him a grateful smile. It hides a cold swell of fear in her belly that has nothing to do with the rise and fall of the wherry as it strikes out past the Paris Garden towards Whitehall. From the moment Rose Monkton came flying through the door, her mistress has been pondering the likelihood that one of the most powerful men in the kingdom will happily lay aside whatever occupies him this evening just to grant an audience to a Bankside tavern owner without a tavern.

In the event, she doesn’t recognize the gatekeeper on duty at Cecil House. He, in turn, does not recognize her. And even if he did, Bianca knows he is but the first thorn bush in a whole thicket set around the queen’s secretary that grows denser, the more one tries to penetrate it. She adopts a tone she thinks might sound authoritative.

‘I am the wife of one of Sir Robert’s physicians,’ she begins. Even now it sounds strange to her. ‘I must speak to Sir Robert. It’s urgent.’

‘Sir Robert’s physician, you say?’

‘Dr Nicholas Shelby. You must have seen him pass through these gates before now.’

The gatekeeper nods. ‘The young fellow who don’t look like a physician?’

‘That would be him.’

‘And you’re his wife?’

‘Yes. I am Mistress Merton.’

‘But you said you were Dr Shelby’s wife.’

‘I am.’

‘So why are you Mistress Merton and not Goodwife Shelby?’

‘I am both,’ she says, having little time for the English practice of subsumption by marriage.

‘How can a body be two people at once?’

‘I have to speak to Sir Robert.’

‘What about?’

‘A privy matter.’

‘I’ll have to know more before I can pass a message.’

Bianca’s jaw stiffens. ‘I told you, I’m the wife of his physician. It’s about a pustule that needs lancing.’

Even in the dusk Bianca can see the relish in the gatekeeper’s eyes. He’s savouring how the revelation will play with the other servants when he tells them the son of the Lord Treasurer has a boil somewhere on his august person.

‘A pustule – whereabouts?’

Bianca smiles sweetly at him.

‘It’s guarding his gatehouse.’

Less than ten minutes later she finds herself sitting on a window seat beside a tall column of mullioned glass stained orange by the setting sun, staring fixedly at a mantelpiece carved with the Cecil insignia, and trying to slow the frenzied beating of her heart by silently counting the monotonous ticking of a fine French clock.

Nicholas has no idea how much time has passed since Winter pushed him through the door of this new chamber. But at least his accommodation has improved. They have taken him from the old carpenter’s store to a minor wing of Essex House. He can sense, perhaps by the stagnant closeness of the air, that it has been used as a depository for things no longer necessary to the earl’s comfort: furniture that is out of fashion, boxes of clothes that now fail to dazzle, people… The floor is tiled, a white-and-red zigzag that makes him think of blood running over the planks of a scaffold. He wonders if this is where they kept Lopez while they plastered over the gaping cracks in their case against him.

He is lying on single narrow cot, not quite wide enough to take a fully-grown man. The coarse woollen sheet scratches through the linen of his shirt. It fails miserably to soften the hardness of the boards beneath. If he rests his arms by his sides, the limbs are forced inwards across his body; if he extends them, the edges of the cot are hard against his elbows. Either way, he cannot sleep. Perhaps that’s the aim. Wear him down. Exhaust him. Confessions can be wrung out of a man without recourse to hot iron or cold fists.

Sometime after Winter had left he heard a key turning to unlock the door. Thinking the interrogation was about to begin again, he lifted himself off the cot, preferring to face them on his feet than prone like a beaten dog. But it had only been a servant bringing a plate of bread and cheese and a pot of small-beer.

He wonders if Rathlin and Athy will come again. Perhaps Essex will send someone more significant. If it is Chief Justice Popham, or Attorney General Coke, or even Essex himself, then the thread of hope will unravel. His greatest fear is that they will come accompanied by the infamous Richard Topcliffe, the queen’s tame torturer.

To master the fear inside him, and to suppress his longing to be with Bianca, in his mind he runs through his knowledge of Italian vocabulary. In their time at Nonsuch over the winter, she helped him improve his limited skill in the language. For him it had been just a diversion. His real motive had been to strengthen the muscles in her throat, to aid her recovery from the laryngotomy he had been forced to perform in order to save her life, after the smoke from the fire that destroyed the Jackdaw had almost killed her. He reaches benefico before something resembling sleep takes him.

A key turning in the lock brings him suddenly awake. Two faces emerge from the blackness, each turned into a devil’s mask by a sudden flare of candlelight. One of the masks speaks.

‘You are to come with us, Dr Shelby.’

The voice is Rathlin’s. Nicholas presumes the second demon is Athy. Rising stiffly from the cot, he asks, ‘What hour is it? Where are you taking me?’

He receives no answer. Despite his aching limbs, he thinks of punching the closest devil’s face and making a break for it. But beyond the compass of the candlelight there is nothing but blackness. He has no idea where to run to. So with Rathlin leading and Athy as rearguard, he walks hesitantly into the depths of Essex House.

After a meandering journey that costs him barked shins and several harsh prods in the back, a door looms out of the night, framed by the faintest sliver of light. Nicholas almost walks into Rathlin’s back as he stops. He sees the candle flame move diagonally, extinguished and then relit as it passes across the silhouette of the lawyer’s body. He hears Rathlin’s fist rap twice on the door. The next moment he is standing, blinking furiously, in a grandly appointed room lit by more candles than he can count. Their flickering light makes a dancing cloudscape on the gleaming white plaster ceiling, casting shadows from the ornate moulding. On the far wall, an oak gallery extends from one side to the other above a row of paintings that he takes to be leading members of the Devereux family.

In the centre of the room stands a tall man, a little younger than himself. He sports a sandy-coloured beard and a doublet seeded with more pearls than a diver could harvest in a year and still have lungs to breathe with. He eyes Nicholas with detached disappointment, as though he’s bought a hunting dog on a false recommendation. Nicholas knows him at once. It is Robert Devereux, the Earl of Essex.

But it is the familiar little figure beside him, reduced even further by his neighbour’s magnificence, his crooked stance a blemish on this otherwise-pristine canvas, that truly draws Nicholas’s attention. It is Sir Robert Cecil.

Nicholas’s heart sinks. He has always known that friendship and loyalty would mean nothing to Lord Burghley’s crook-backed son if he thought the realm’s safety was at stake. Look how he had turned his back on old Lopez.

And then, to his astonishment, he hears a woman’s voice. It comes from his left, in a pool of shadows the candlelight has not penetrated. And it is even more familiar to him than Cecil’s broken outline.

‘Mercy, Husband!’ Bianca Merton says. ‘I let you out of my sight for one moment and you wander off like a brainless goat in an olive grove.’

Robert Cecil’s men have brought a spare horse for Nicholas to ride the short distance from Essex House to the Strand. He wonders grimly if that’s because Cecil and Bianca had expected to find him beaten and unable to walk unaided.