Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: The Jackdaw Mysteries

- Sprache: Englisch

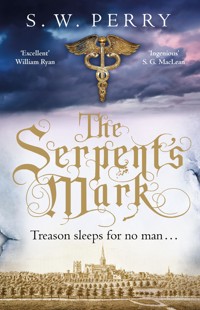

'MY FAVOURITE HISTORICAL CRIME SERIES' S. G. MACLEAN 'A RATTLING GOOD READ' WILLIAM RYAN ---------------------------------- Treason sleeps for no man... London, 1591. Nicholas Shelby, physician and reluctant spy, returns to his old haunts on London's lawless Bankside. But, when spymaster Robert Cecil asks him to investigate the dubious practices of a mysterious doctor from Switzerland, Nicholas is soon embroiled in a conspiracy that threatens not just the life of an innocent young patient, but the overthrow of Queen Elizabeth herself. With fellow healer and mistress of the Jackdaw tavern, Bianca Merton, again at his side, Nicholas is drawn into a sinister world of zealots, charlatans and dangerous fanatics... Praise for S. W. Perry's Jackdaw Mysteries 'S. W. Perry is one of the best' The Times 'Historical fiction at its most sumptuous' Rory Clements READERS CAN'T GET ENOUGH OF THE SERPENT'S MARK 'Outstanding Elizabethan thriller' ***** 'Gripping from start to finish' ***** 'An absolute must-read' ***** 'What a plot!' ***** 'Exciting and compulsive reading' *****

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 599

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published in Great Britain in 2019 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © S. W. Perry, 2019

The moral right of S. W. Perry to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 78649 496 2

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 78649 497 9

E-book ISBN: 978 1 78649 499 3

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

For Lilian and Vera Jones

Hic locus est ubi mors gaudet succurrere vitae.(This is a place where the dead are pleased to help the living.)

INSCRIPTION IN THE ORIGINAL THEATRE OF ANATOMY AT THE UNIVERSITY OF PADUA 1594

Physicians are like kings – they brook no contradiction.

JOHN WEBSTERThe Duchess of Malfi1614

Tilbury, England. Winter 1591

In the dusk of a desolate November evening an urchin in a mud-stained and threadbare jerkin, long-since stolen from its rightful owner, hurries along the Thames foreshore beneath the grim ramparts of Tilbury Fort. The chill east wind claws at his puckered pale flesh. The hunger that has driven him down to the narrowing band of shingle gnaws within him, as if it would tear itself out of his belly and go crawling off by itself in search of sustenance elsewhere. He is risking the tide because he knows a place where the oysters are plump and good. On balance, the strand is a safer route than striking inland in the gathering darkness.

His destination is a small channel that runs deep into the Essex shore, a wilderness of marsh and reed, of dead-end tracks that lead to creeks where you can drown in stinking mud before you can get to the Amen at the end of the Lord’s Prayer. He knows this because the wasteland is where he lives, on its southern fringe, in a ramshackle camp of vagabonds and peddlers, swelled by the destitute and the maimed from the wars in Holland and by discharged sailors from the queen’s fleet.

The river is the colour of the lead coffin he once saw when he broke into a private chapel to get out of a storm. It is studded with ships: hoys and flyboats from Antwerp and Flushing, barques from the Hansa ports of Lübeck and Hamburg, fur traders from the white wastes of Muscovy. As night approaches, they are beginning to dissolve before his eyes, like old coins tossed into oil of vitriol. All they leave behind is the tarry smell of caulked timber and the tormenting scent of food cooking on galley hearths.

Before the boy can reach the channel he must first climb over the great iron chain that runs out into the water, the boom that blocks the river lest the Spanish come again, as they did in ’88.

He is unwilling to jump the chain because the hunger has given him cramps in the stomach. He’d crawl under it, but that would mean slithering through pools of rank green slime. So instead he puts one tattered boot into a slippery iron link and starts to ease himself over.

And as he does so, something amongst the rotting kelp that clings to the chain detaches itself and drops to the pebbles.

A crab! A dead crab.

Dare he eat it? He’s ravenous enough. But how long has it been there, trapped amongst the weeds and the barnacles? The urchin knows you can die from eating bad food. It makes you double up like a sprat being fried in a pan. It makes you scream. He’s seen it happen.

But famine has made him canny. He knows exactly what to do. He’ll wash the crab clean of mud in the nearest pool, take a long sniff beneath the carapace and judge then if it’s worth breaking open.

It is only when he lifts the crab from the pebbles that the boy realizes it is not a crab at all.

It is a human hand.

Contents

Title

Copyright

Tilbury, England. Winter 1591

Part 1: The Physician from Basle

1: Nine months earlier. 23rd February 1591

2: Gloucestershire. The next morning

3: London, 4th March 1591

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Part 2: The Beech Wood

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Part 3: Tilbury

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Author’s note

Landmarks

Cover

Title

Start

PART 1

The Physician from Basle

1

Nine months earlier. 23rd February 1591

It is a day made for second chances, a day ripe for confession, for penitence, for admitting your sins and seizing that unexpected God-given chance to start afresh. A dying storm has left thin wracks of ripped black cloud hanging in the saturated air, above a pale empty world awaiting the first brushstroke. It is simply a matter of applying the paint to the canvas. Let today slip by unused, and Nicholas Shelby – lapsed physician and reluctant sometime spy – knows he must return to London, no nearer to accepting the new life he’s been so cruelly dealt than when he left.

His father has sensed it, too.

‘Your Eleanor died in August last,’ Yeoman Shelby observes with devastating calmness, as the two men shelter from the last of the downpour in the farm’s apple press. ‘It’s now almost March. Seven months. Where were you, boy? Where did you go?’

How much of an answer does a father need? Nicholas wonders, close to shivering inside his white canvas doublet. Would it help to know that for a while I was busy drinking myself stupid in any tavern I could find that hadn’t already banned me? Or that I was losing every patient I had, because word had soon spread that Dr Shelby was raging in his grief like a deranged shabberoon? Or that I was busy rejecting everything I learned at Cambridge – attended at a cost you could scarcely bear – because when the time came and Eleanor and the child she was carrying had need of it, my medical knowledge turned out to be little more than superstition? Or that, on top of everything else, there had been a murderer I had to stop from killing again?

There are some questions, Nicholas thinks, that should remain for ever unanswered, if only for the sake of those who ask them.

‘How could you do that to us, boy – vanishing off the face of God’s good earth like that?’ his father is saying, his words delivered to the dying rain’s slow drumbeat. ‘Your brother wore himself thin, searching that godless place called London for a sign of you. Your mother wept like we’d never heard her weep before. Do you not know we loved Eleanor, too?’

Nicholas has been dreading this moment ever since he returned to Suffolk and the Shelby farm. Now he sits on the cold stone rim of the press, straight-backed, head up, a damp curl of wiry black hair slick against his brow, unable to give in to the desire to slump, because a Suffolk yeoman’s son is not grown to wilt, even if the weight of all that’s happened since Lammas Day last is almost too much for his broad countryman’s shoulders to bear. Sickened by the excuses he hasn’t even tried to make yet, at first all he can bring himself to say is ‘I know. I’m sorry.’

Yeoman Shelby has rarely struck either of his sons, and not at all since they’ve grown to manhood. But as he comes closer, Nicholas wonders if he’s about to land a blow in payment for the extra pain his youngest has caused the family by his vanishing. He catches the heavy, musty smell of his father’s woollen coat, the one he’s worn in winter for as long as Nicholas can remember. Dyed a now-faded grey, it smells as though it’s been buried in a seed basket for all of Nicholas’s twenty-nine years. But the scent is oddly comforting. Nicholas has the overwhelming urge to reach out and cling to the hem, as if he were an infant again.

‘The only way I can explain it is this,’ he says, staring at his hands and thinking how his fingers, nicked and coarsened by boyhood summers helping with the harvest, seem so unsuited to healing work. ‘Imagine if you woke up one morning and discovered that all the wisdom accumulated over fifteen hundred years of husbanding the land didn’t work any longer – that you couldn’t grow anything any more; that you couldn’t feed your family.’

‘It’s called an evil harvest, boy. It’s happened before.’

‘Exactly! And there was absolutely nothing you could do about it, was there?’

Nicholas looks up at his father with moistening eyes. He snorts back the tears, frightened that he’s about to weep in the presence of a man who has always seemed immune to sentiment. ‘That’s how it was when I tried to save Eleanor and our child,’ he says thinly.

His father lays a hand on his son’s shoulder. ‘I know you well enough, Nick. You would have moved heaven and earth, if you but could. But sometimes, boy, it’s just the way God wants things to happen.’

Nicholas gives a cruel laugh. ‘Oh, I’ve heard that said before. Did you know the great Martin Luther – fount of this new religion we’re all supposed to embrace so unquestioningly – tells me in his writings that God designed women to die in childbirth! He says it’s what they’re for! Well, for the record, I’ll have none of such knowledge.’

‘Parson Olicott would say that what you learned at Cambridge is God’s wisdom revealed through man,’ his father replies, caution in his runnelled face. ‘He’d say our Lord would offer us no false remedies. He’d call you a blasphemer for suggesting otherwise.’

‘The remedies Parson Olicott gets called upon to administer, Father,’ says Nicholas, running his fingers through a tangle of hair that the rain has flattened to his scalp like black ribbons discarded in a ditch, ‘are for ills of the soul, not the body.’

‘But if the soul is in good health, does not the body follow?’

Though a humble farmer, a man who only learned to write when he was forty, his father has just summed up the current thinking of the College of Physicians in a nutshell.

‘That’s what we’ve thought for centuries,’ Nicholas says. ‘That’s what the books tell us: bring the body into a balance pleasing to God. They instruct us to bleed the patient from a particular part of his body if the sanguine and choleric humours are out of kilter; purge him if the melancholic humour suppresses the phlegmatic; read the colour of his water – and always make sure the stars and the planets are in favourable alignment, before you do any of it. Then present the bill. And if it all goes wrong, say it was God’s will – or the stars were inauspicious.’

His father kneels and stares into his son’s eyes with the stoic acceptance of the cycle of life and death, of hope and disappointment, that a man who relies on the fickleness of the earth for his survival must learn. His face looks carved out of holm oak. You’re barely fifty, thinks Nicholas, yet you look like an old man. Is it the toil? Or have my own actions aged you? He settles for what his mother and his sister-in-law, Faith, have always claimed: grubbing away at the earth makes Shelby men look older than their years.

‘Listen to me, boy,’ his father says with a surprisingly gentle smile that looks out of place on such a hard-used face. ‘Thrice in my lifetime I’ve heard Parson Olicott tell me I’m to forget my religion and believe in a different one. Every Sunday – until I was about fourteen – he’d tell me the Pope was a fine Christian man, an’ that for my spiritual education I was to study the pictures of the saints in St Mary’s…’

Nicholas wonders what that weathered stone Saxon barnacle, where the Shelby family now have their own pew almost within touching distance of the altar, has to do with his present agony; but he’s learned long ago that when his father embarks on one of his homilies it’s best not to interrupt.

His father continues. ‘Then one Sunday shortly after King Henry died, I hear Parson Olicott announce, “King Edward says the Pope is the Antichrist!” Well, you could have knocked me down with a feather. After the sermon, Parson Olicott hands us lads a bucket of whitewash.’ He makes a painting gesture with one hand, the fist clenched. ‘“Cover up those paintings of the saints,” orders old Olicott, “’cause now they be heretical!”’

Nicholas has stared at the plain walls of St Mary’s every Sunday for as long as he can recall, usually with intense boredom. It has never occurred to him that his father was one of those who’d done the whitewashing.

‘Took us lads ages, I can tell you,’ Yeoman Shelby says. ‘But the next thing I know – around the time I was paying court to your mother – there’s Parson Olicott proclaiming that Edward is dead, Mary is queen, and the Pope is once more our father in Christ. Imagine it!’

Nicholas indulges his father and imagines.

‘“Change the prayer book!” says Olicott. “Bring out the choir screens again” – we’d hidden them in Jed Arrowsmith’s barn. “Scrub off the whitewash! The bishops what made us paint over those saints are all now heretics and must burn for it!”’ Yeoman Shelby sighs, as though all this variable theology is beyond the understanding of a simple man. ‘To tell the truth, Nick, when we got the whitewash off, I was surprised those paintings had survived. But survive they had. Stubborn buggers, those Catholic saints. Didn’t last, of course. Barely five years on, Bloody Mary is dead, we’re all singing hosannas for Queen Elizabeth, and the Pope is the Devil’s arse-licker again. And what’s old Olicott preaching?’

‘Fetch the whitewash?’

His father nods. ‘Exactly. What I’m saying to you is this: there ain’t ever such a thing as certainty, boy. Maybe in the next world, but not in this. So don’t you worry your young head about whether or not your old father can handle it when his clever physician son has a crisis of belief. Because what really grieves us, Nick – what really makes us weep – is that when your world was turned on its head, when you had need of us most, you didn’t come home.’

For a moment there is only the slow dripping of water on the pressing stone. Then Nicholas is in his father’s arms, his chest heaving like a man drowning, sobbing with a child’s bewilderment at unjustified injury.

Outside, the rain is starting to ease. The old thatched houses of Barnthorpe are beginning to take on their newborn, sharper forms. When the two men walk back to the Shelby farmhouse, Nicholas feels somehow lighter. Certainly more resolute. Confession has done him good – even if it’s only a partial confession.

Because there’s something else Nicholas hasn’t admitted to his father. He hasn’t told Yeoman Shelby that a part of his son – a small part to be sure, but even the smallest canker can still presage a greater infection – now belongs to one Robert Cecil.

‘Careful now, Ned. Master Nicholas is not here to set your bones if you fall!’

Bianca Merton grasps the ladder with both hands, letting her weight bear down on her left foot, which is set firmly on the bottom rung. Above her, Ned Monkton sways precariously as he leans out over the lane. He looks like a bear that’s climbed to the top of a maypole and got stuck there. Cursing, he tries to attach the newly made board beside the sign of the Jackdaw. It takes him a few minutes and an excess of profanities, but before long the new banner is in place: the unicorn and the jackdaw swaying side-by-side in the breeze. Southwark now has a tavern and an apothecary, all in one. You can forget your tribulations with a quart of knock-down, and get colewort and hartshorn for the resulting hangover, in the same place.

‘Don’t that look a fine sight?’ says Rose, Bianca’s maid, as she admires the scene – though whether it’s the apothecary’s sign or the sight of Ned’s hugely muscular legs wrapped around the ladder is somewhat unclear to Bianca.

‘I wish I could have seen the faces of the Grocers’ Guild when they signed my licence,’ Bianca says, sweeping her proud, dark hair from her brow. ‘They’ve been trying to shut me down since the day I arrived. And now I’m legal! Who would have imagined it? Bianca Merton of the Jackdaw, a licensed apothecary!’

Whatever her curative talents, Bianca makes an unlikely tavern-keeper. She’s slender, with a narrow, boyish face topped by a trace of widow’s peak, and extraordinarily amber eyes that gleam with a mischievous directness. Having been born of an Italian mother and an English father, her skin still boasts a healthy lustre infused by the Veneto sun, despite all that three years in Southwark have contrived against it.

‘Shame a someone isn’t here to see it,’ says Rose, a plump, jolly young woman with a mane like tangled knitting. ‘How did he manage it? I thought he were out of all regard with them physicians in their pretty college on Knightrider Street.’

‘He called in a favour, Rose,’ Bianca says wryly. And beyond that she will not go. The memories of the horror she and Nicholas endured together are still too raw. Before he left for Suffolk to make his peace with his family, they’d scarcely spoken of it between themselves, let alone with outsiders. The nightmares still come to her, though less frequently now. When they do, they have a terrifying fidelity about them. Once again she is back in that vile place deep in the earth, feeling her flesh tense as it awaits the draw of the scalpel. She consoles herself with the knowledge that no more bodies will wash up on Bankside. The man who put them in the river has met his just reward, thanks to Dr Nicholas Shelby, who came to her as a talisman from out of that very same river.

She wonders what Nicholas is doing now. Is he reconciled with his family? Do the ghosts of his wife and child haunt him still? Will he return to Bankside, as he promised? And how will she feel about him, if he does?

He’s so very different from the men she’d known in Padua. A yeoman’s son from the wilds of Suffolk who’d found the intellectual courage to battle the stultifying hand of tradition during his medical studies is as unlike a fashionably clad libertino as she can possibly imagine. She scolds herself for the sudden, unexpected surge of jealousy that comes with knowing how capable of love Nicholas is, despite his stolid roots. It would be so much better, she thinks, if he could devote that love to the living, and not the dead.

Her reverie is broken by the sole of Ned’s boot on her hand as he descends the ladder.

‘God’s mercy!’ she cries, snatching her hand away and shaking it vigorously. ‘Have a care where you’re putting your feet, you clumsy buffle-head!’ Catching herself using the vocal currency of the London streets, she smiles. She thinks, soon I shall have lost that accent Nicholas says he can hear in my voice whenever I get fractious. Soon I shall be as English as Rose.

Ned Monkton, just turned twenty-one, built like King Henry’s great Mary Rose – and just as liable to capsize, if too much liquid flows in through an open port – steps back to earth. He scratches his fiery auburn hair and slaps his belly with his great fists. ‘There now, Mistress,’ he says, looking up at the two signs, ‘they can’t beat that at the Turk’s Head or the Good Husband, eh?’

‘You’ve hung it upside-down,’ says Rose.

And for just a moment Ned is taken in.

They’re an odd pair. Rose is as ungovernable as a sack of wild martens. Her idea of a day’s leisure is a trip to Tyburn to watch a good hanging. Ned used to be the mortuary warden from St Thomas’s hospital down by Thieves’ Lane. Smiling, Bianca remembers her mother’s firm conviction: there’s always someone for someone.

It’s good to see Ned above ground now, she thinks, instead of deep in the hospital crypt, surrounded by the dead. He’s even getting some colour back in his face. Since Nicholas set off for Suffolk, Ned has taken his place as the Jackdaw’s handyman and thrower-outer-in-chief. There’s been not a jug spilt in anger since. And with Rose beside him, he’s beginning to recover a little from what befell young Jacob, his younger brother, whose death gave Nicholas his first lead in tracking down the man they all now describe – in lowered voices that still have an echo of dread in them – as the ‘Bankside butcher’.

Bianca looks up at the two signs again, satisfaction welling in her breast. A measure of cautious contentment stirs within her. She waves happily at a fee of young lawyers – the invented collective noun slips into her head, unbidden. They’ve come across the bridge for the stews and the cock-fights. They’ll be lucky to get back to Lincoln’s Inn with the hose they put on this morning. She receives their clumsy, ribald replies as down-payment and ushers them towards the Jackdaw’s entrance.

And then her taproom boy, Timothy, comes running down the lane. In the excitement of raising the apothecary’s sign, she’d almost forgotten she’d sent him down to Cutler’s Yard to pay the sign-maker.

‘Mercy, young Timothy, what’s the alarm?’

‘The watermen say a new barque will drop anchor in the Pool tomorrow,’ he tells her breathlessly. ‘She’s coming up from the Hope Reach on the morning tide. Four masts!’ He raises the appropriate fingers to indicate the wonder of it. ‘Imagine it: four!’

For the denizens of Southwark, a newly arrived ship is like a freshly killed carcass to a wolf. There are victuals to be replenished at twice the going rate; goose-feather mattresses for men who’ve spent months sleeping on salty boards; a predictable uncertainty of the legs, which makes lifting a purse that much easier; an outlet for desires that until now have been only solitarily satisfied. It’s been this way since the Romans were here, and Bianca Merton isn’t about to pass on the opportunity.

‘From which state is she? Do they say?’ she asks, factoring translation into the equation – French and Spanish mariners take less time to serve than those from Muscovy, and Moors don’t take drink at all.

‘Venice,’ says Timothy eagerly, with not the slightest comprehension of just how much powder he’s about to ignite. ‘She’s the Sirena di Venezia.’

It is the day after the story of the whitewash. Being a Wednesday, it is market day and Woodbridge is busier than Nicholas can remember. Well-heeled wool merchants, weavers, tanners and saymakers bellow at each other in the shadow of the session house like sailors in a storm. Stolid, boxy-faced Dutch refugees from the war in the Low Countries greet each other expansively and puff on their long clay pipes. In the stocks on Market Hill, scolds, habitual drunks and other disturbers of the queen’s peace look on with sullen resignation.

Once the carts are set up, there is really very little for Nicholas to do. His father, sensing his restlessness, says, ‘Away with you, boy! Find your ease where you choose.’

‘Are you sure?’

‘With a physician in the family, they’ll think I’m after robbin’ them.’ It’s meant kindly, but there’s a grain of truth in Yeoman Shelby’s words.

With no real purpose in his steps, Nicholas heads down to the river.

After years of helping his father scatter seeds on the ploughed fields, he has a mariner’s sway in the shoulders when he walks. At Cambridge, the sons of gentlemen took it for upstart arrogance and beat him for it – until the day he forgot his place and broke the wrist of a minor baronet-in-waiting.

He’s stopped by people he knows at least half a dozen times before he reaches the foot of Market Hill. They observe that he’s put on weight; that he’s thinner; that he looks younger without his beard; that he looks older. In truth, he knows exactly what he looks like: a yeoman’s son – possessed of all his former rough edges. The man of medicine who spent a summer in Holland serving as surgeon to the Protestant army of the House of Orange, or the London physician, is someone else entirely. None of them ask why he’s returned. None of them ask him about Eleanor, though he can see the question clearly enough in their eyes.

Along the quayside the little hoys bound for London are loading up with cheese and butter. Scottish salt-boats and Suffolk herring-drifters disgorge their cargoes by the barrel-load. The smell of pitch and freshly sawn timber reaches him from the small shipyard. It was from this very quay, he remembers, that he departed for Holland, the ink barely dry on his medical diploma. ‘The Dons are murdering innocent Protestants in their beds,’ he’d explained to Eleanor when he’d told her of his intention, his head brimming with idealistic rage at what the Spanish were doing to good Dutch Protestants across the sea. ‘Sir William Havington has raised a company to aid the House of Orange in their just revolt. They need a surgeon.’ Her reaction had astounded him. Instead of admiration, there had been only cold-eyed anger. He’d discovered later that she’d taken his pompous talk of duty and responsibility for a sign that he was having second thoughts about the wedding. He can sense her now, standing beside him on the day the Good Madelaine sailed, refusing to weep, accepting his farewell with the pretence of indifference, a determined set to her jaw.

There had been others taking leave of loved ones that day, he recalls. Sir William Havington himself – a gentle white-haired soul who had long since retired from the profession of arms – had come to wish good fortune to the company that bore his name. He had made a point of shaking hands with everyone, from its new commander down to the lowliest recruit. Behind his smile, something in Sir William’s face, some sadness he couldn’t quite hide, had told Nicholas that a test was coming – a test that would make a bloody mockery of all their boisterous, innocent confidence.

And he’d been proved right. Within a month a dozen of them were dead. By winter, several more had returned to England maimed, condemned to wander the open roads begging for alms, because the House of Orange had somehow neglected to pay their promised bounty. As for those who’d remained in Holland – Nicholas included – all that had kept them from becoming a fleeing mob of desperate, starving fugitives – or, worse still, prisoners of the Spanish – had been the iron will and extraordinary courage of the man who had taken Sir William’s place at their head: his son-in-law, Sir Joshua Wylde.

And there had been a third figure on the quayside that day, Nicholas now recalls: Sir Joshua’s son, Samuel. He remembers a thin, pale lad with fair hair and a worried face. The boy had wanted so much to follow his father, but his youth and sickliness had made that impossible. You couldn’t have known it, Samuel, says a voice in Nicholas’s head as he gazes out over the leaden flatness of the estuary, but you were luckier than many of those brave young lads with whom – even though you were still a child – you so fervently longed to trade places.

On a whim, Nicholas leaves the quayside and follows the track along the bank. He knows where he’s heading, though he won’t yet admit it to himself.

I’ll just take a quick glance from the riverbank, that’s all… See if the house fits my memory… It can’t hurt…

The grey expanse of the estuary cuts through the flat bleakness on its serpentine journey towards the sea. He catches the familiar fetid reek of tidal mud on the wind. It reminds him of the smell of flooded graves.

And then there it is: a modest but gracious thatched manor house set back from the creek, a well-grazed lawn sloping down to a reed-bed and a private jetty – Sir Joshua Wylde’s Suffolk home. The place he prefers over the family seat in Gloucestershire, because here in Suffolk there is no sickly Samuel to remind him that he has no healthy heir to whom he can entrust Sir William Havington’s legacy.

For a moment Nicholas thinks he has stepped back in time. The picture is almost exactly as he remembers it, even down to the thirty or so lads – a thin leavening of older men amongst them – who squat in expectation in a semicircle on the grass. And at their centre, standing as though he’s just forced a breach in a rampart, is the fiercely bearded resplendence of Sir Joshua himself; a little older perhaps, a few more lines around his eyes from the permanent black scowl, the points of his jerkin stretched somewhat tighter around the belly, but undoubtedly the same mad-gazed hammer of the heretic.

If Nicholas believed in ghosts – as all right-minded people do – he’d think that’s what these figures are – wraiths from the past. But he can hear Sir Joshua’s voice as clear and as real as the exchanges on Market Hill, and he realizes that he’s happened upon another company in preparation for the war in the Netherlands, a war that has been raging now for more than twenty years and shows no apparent sign of ending.

‘Your average Don is born with a bloody heart,’ Sir Joshua is telling the entranced company. ‘He drinks slaughter with his dam’s milk. He has no place on a civilized earth. It will be your God-given task to tear that heart out of his filthy, blaspheming body with your bare hands, if needs must!’

A rousing cry goes up in reply, though from what Nicholas can judge from the earnest faces, the nearest these lads have yet come to slaughter is catching coney for the pot.

And then Sir Joshua stiffens, as he spots Nicholas watching him from the path. A slow smile breaks through the great foliage around his face. It reminds Nicholas of an old tree trunk slowly parting after the axe blade has done its work. ‘God’s blood! As Christ is my saviour – look what the wind has brought!’ he booms, beckoning with one leather-clad arm for Nicholas to step forward. ‘This, my fine bully-boys, is Dr Nick Shelby. Came with us to Gelderland in ’87. Callow as a country maiden when he joined. Best damned surgeon in the whole Orange army when he left. Almost as good as that scoundrel Paré, and he was a Frenchie, so he don’t count.’

As Sir Joshua’s fist closes around his own proffered hand, pumping his arm alarmingly, Nicholas offers an embarrassed grin to the upturned faces. He has never found Joshua Wylde an easy man to like. But he knows full well that, like every other fellow in Sir William Havington’s company who returned, he owes Sir Joshua his life. He wonders how many of these eager fellows he’ll bring safely home.

With another barrage of blood-curdling oaths fired at the Spanish, Wylde instructs his recruits to attend to their preparations, and insists that Nicholas share a jug with him inside the house.

Stepping into the shadows of the hall, Nicholas finds the way almost blocked by a mountain of chests and sacks containing the necessities of comfortable campaigning: crates of malmsey, mattresses and pewter, polished plate armour, stands of matchlock muskets. A servant is dispatched and hurries back with sweet Rhenish in silver cups.

‘Surely you’re not in practice here in Suffolk,’ Sir Joshua says as they drink. ‘They still look to magic and wise-women in these parts.’

What can I tell him, Nicholas wonders as he feels his stomach churn; how can I explain what I’ve been through, to someone who thinks grief can be dispensed with by a quick prayer and a toast raised to the dead?

‘After I came back,’ he begins tentatively, ‘I did set up in practice in London, but—’

Sir Joshua – who conducts conservations the way he assaults heavily defended bastions: relentlessly – doesn’t wait for Nicholas to finish his reply. ‘Married yet?’ he asks bluntly. ‘Sons? Healthy sons?’

‘Sadly, no.’

‘Don’t tarry too long, lad. Greatest reverse of my life, not having a healthy son,’ Sir Joshua tells him, and for a lingering moment Nicholas wishes he’d stayed beside the session house with his father.

‘I thought you were still in the Low Countries,’ Nicholas says, hoping Wylde won’t notice how moderately he’s drinking his wine.

‘I took leave for Sir William’s funeral, and to muster new volunteers.’

‘Sir William – dead?’ Nicholas has a vision of the white-haired Sir William Havington shot down in one last, ill-advised foray against the Spanish.

‘In his bed. Quatrain fever, or so the physician said.’ Sir Joshua raises his cup to toast his late father-in-law. ‘Here’s to a life honourably lived.’

Nicholas acknowledges the toast and takes a small sip of wine.

‘Rhenish not up to scratch?’ asks Sir Joshua quizzically.

‘It’s excellent. It’s just that I don’t sup so much now, not after…’ Nicholas pauses, deciding there are some things Joshua Wylde doesn’t need to know. ‘And your son? How does Samuel fare?’

Sir Joshua stares into his cup as though expecting to find the answer written in the lees of the wine. ‘Don’t mistake me, Nick. I hold the boy in the deepest affection, always have.’ His mouth twists with ill-disguised guilt. ‘But I must confess it: to be long in his presence troubles me deeply. His sickness is an affront to a man like me. A reproach from God.’ He spreads his hands as though seeking sympathy. ‘The Wylde family won its first honours at Crécy. We’ve been warriors, every one of us, from that day hence. Why the good Lord chose to reward my services to Him with an heir who suffers from the falling sickness – well, I must have offended in some manner. Perhaps He thinks I haven’t slaughtered enough heretics for Him yet.’ Wylde takes his deep draught of Rhenish as though it were a medicine. ‘I do my best for Samuel. He is not alone. I make sure he has company – companions.’

‘Companions?’

‘He can’t mix with the village lads, you see. They taunt him. They say he’s possessed by devils.’

‘That’s what a lot of ignorant folk say about the falling sickness.’

‘Young Tanner Bell is with him. Came across from Havington Manor,’ says Wylde. Then he notices the blank look on Nicholas’s face. ‘Tanner – Dorney’s younger brother. You remember Dorney Bell, surely.’

Nicholas remembers Dorney all too well – a beanpole in a dented steel breastplate that made him look like a stand on which to hang plate armour. He remembers Dorney’s country-boy ability to have the company laughing, even in the worst of the Dutch rain. But neither breastplate nor humour had saved Dorney Bell. He’d died in Nicholas’s arms on his nineteenth birthday, a Spanish ball lodged in his spine.

‘I really should be thankful Samuel still lives,’ says Wylde, emitting a grunt of guilty laughter. ‘There were physicians who told me he’d never see fifteen summers.’

‘The falling sickness is indeed a cruel malady, Sir Joshua.’

‘He’s as weak now as his mother was, and she was scarcely seventeen when she died. Had she been made of hardier stuff, she might have survived the whelping.’

‘Then perhaps there’s still hope.’ Nicholas says, trying not to wince at Wylde’s apparent callousness.

‘Oh, there’s hope aplenty, according to the new doctor my wife has engaged.’

Nicholas’s eyes widen. ‘You’ve remarried?’

‘Isabel,’ Wylde explains portentously, seeing the look of surprise on his guest’s face. ‘We were wed in Utrecht last year.’

‘She’s Dutch?’

‘English to her soul. She’s a Lowell.’ He frowns, as though the lineage escapes him. ‘Don’t know them, myself. But she’s handsome enough. Young, too. Should breed well.’

‘Forgive me,’ says Nicholas with a smile, ‘but I never thought of you as the wooing kind. I thought there was no space in your heart for anything but killing Spaniards.’

‘Nor is there, Nick. But perhaps she might whelp me an heir – one with the proper constitution to take up the work when, like Sir William, I am aged and can no longer wield a sword.’

‘How did you meet?’ Nicholas asks, only too happy to keep the conversation away from his own marital history.

‘She sought me out.’

Wylde has never struck Nicholas as the likely victim of an opportunistic woman, however comely.

‘She’d heard of my reputation!’ Sir Joshua says, just to make things clear. He leans forward until his beard juts close to Nicholas’s face and adds in a conspiratorial whisper, ‘Swore she would have no husband other than a Christian knight who knew his duty to the new religion. What was I to do? I can’t sire an heir to the Wylde name off any common Hogen-Mogen whore, can I?’

‘No. No, of course not,’ replies Nicholas, almost lost for words. ‘Is Lady Wylde here or still in Holland?’

‘She’s at Cleevely. Looking after Samuel. She moved him there from the Havingtons’.’

As Sir Joshua takes another swashing gulp of wine, Nicholas notices a sudden cunning gleam enter his deep-set eyes. ‘Christ’s blood! I swear there was ordination in our meeting today, Nick. I’ll be damned if there wasn’t. Another hour and I’d have been aboard the Madelaine. She’s out in the river, taking on provisions at this very moment.’ He regards Nicholas in silence a while, then tilts his head in contemplation. ‘Busy, are you – at present?’

‘Busy?’

‘A thriving practice? Lots of patients? I can’t believe a man with your skills finds himself underemployed.’

Nicholas shrugs. ‘To be honest, I’m at something of a loose end. It’s been a difficult year…’

‘Then you can do me a service.’

‘I can?’

‘This new physician Isabel has pressed upon me – for Samuel. She’s much taken with him. Says he can work miracles.’

‘That’s a dangerous claim, Sir Joshua.’

‘A modest one, from my experience of physicians, Nick. Saving your presence, of course.’

‘What’s his name? Perhaps I’ve heard of him.’

‘Arcampora. He’s Swiss.’

Nicholas shakes his head and tries not to look too sceptical. ‘Not a name I know, I’m afeared.’

‘I’ve only met him once, in Holland – when Isabel brought him to me. Told me he’d studied at Basle. Swore on his life that he could cure Samuel’s malady.’

‘I don’t wish to dash your hopes, Sir Joshua, but from all I’ve read, the falling sickness is not amenable to any lasting physic. I hope this fellow is not a charlatan. They’re as common as weeds, and just as stubborn, I fear.’

‘Then set my mind at rest.’

‘How?’

‘Visit Cleevely. Give me your honest opinion.’

‘Me?’

‘I’ve seen you at your chosen toil, Nick. As I told my bully-boys out there, you’re the best damned physician I know. You’d be doing me no small service.’

‘I fear I have to tell you something, Sir Joshua—’ Nicholas begins.

But Wylde cuts him off with a wave of his hand. ‘I’ll pay your London prices, Nick – don’t fear on that score. If this Arcampora fellow is as good as he claims, my mind will be set at ease. And if not, then my purse will be all the heavier for your discovery – the fellow’s costing me an earl’s ransom.’

Nicholas has no desire to become entrapped in the briars of Joshua Wylde’s relationship with his sickly son, who clearly disappoints him so. But he remembers the look on Samuel’s face, that day on the Woodbridge quayside: the desperate desire to please an unmatchable father. And, unquestionably, he could do with the money – at present he has no means of income. He thinks it might tide him over while he haggles with the warden at St Thomas’s on Bankside; tries to get his old position back as a part-time physician to the poor of Southwark – a shilling a session, and all the sprains, fractures and hernias you can treat. He’s good at the practical physic. It’s the astrology, the piss-reading and the dogma he has no time for. Besides, were it not for Sir Joshua Wylde, his own bones might even now be mulching some desolate Dutch polder.

So Nicholas accepts the commission – if not exactly gladly. After all, it seems a small price to pay in exchange for the two precious years Wylde’s bravery in Holland allowed him to share with Eleanor.

2

Gloucestershire. The next morning

‘Slow down, y’daft nigit! What’s the hurry? We’ll be lucky to catch a single trout this early in the season.’

Against the rush of the wind, Samuel Wylde barely registers the breathless cry from somewhere behind him. Reaching the crest of the hill, high above the little village of Cleevely, he allows himself a moment to imagine that he’s the only human soul alive on earth: a new Adam, unmarked by sin. With a single thought, he unpeoples the England laid out before him. His two companions – one a tall lad with delicate, questioning eyes; the other a mischievous overstuffed package of youthful rebellion – are instantly swept away. So too are the village boys who throw stones at him and call him ‘Lucifer’s familiar’. And he doesn’t stop there. A snap of his fingers and there is no Queen Elizabeth, no Pope, no Philip of Spain. No lords and ladies. Not even his father, who anyway prefers far-away Holland to the company of his unsatisfactory son. With a single stroke of his imagination, they are all swept away. There is only him – Samuel Wylde – and the songs God sings to him when the light in his head becomes too bright to bear.

From his high vantage point it is easy for him to imagine this unpeopled world. He can see all the way to the far horizon and the Malvern Hills guarding the way into wild Wales. In the fields below him, oxen draw the first plough-blades of the season through the hard earth, for the sowing of the Lenten crop. In their wake come wheeling flocks of birds in search of juicy worms. The sheepfolds look like tiny white clouds fallen to earth from a sky of cold, crystalline blue. Sinking to the cold grass to ease the ache in his legs, he sets down the parcel of manchet bread and cheese wrapped in cloth, to be eaten while the trio fish. His fingers, ungloved and now more than a little blue, are long and delicate. Samuel works tirelessly to keep them still. If they begin to tingle, it is a sure sign another of his paroxysms is on the way – a sign that God is about to shame him once again for the sins he doesn’t remember committing.

But the world that Samuel has conjured is not quite empty. There is a dark shadow somewhere at the edge of it. He is not too sure what to make of the shadow yet. Does it threaten calamity? Or is it a sign that one day soon he will be the same as his two companions, Finney and Tanner: made afresh, unblemished, like the Adam of his imagination. A son whom a father might love.

The shadow is Professor Arcampora. Arcampora, with his strange accent and hawkish profile, his receding hairline, his savagely knife-like nose, and his jutting chin tipped with a spear-point of close-cut beard as dark as jet and shot through with sparks of silver. Arcampora, always clad in his black physician’s gown, which makes him look like a magus straight out of the pages of the Old Testament. Somewhere deep inside Samuel, a last ember of hope begins to glow: perhaps this time it will be different. Perhaps this time, after the procession of stern men of physic that his father has sent to treat him – and to ease his own conscience into the bargain – this one, terrifying though he may appear, might really bring with him a cure.

The extraordinary Dr Arcampora is not working alone, Samuel has discovered. In overheard snatches of conversation between the physician and his stepmother, he has learned that there are others who are concerned for his health. Who these others are was not revealed. All Samuel knows is that they are brothers, and they live beyond the Narrow Sea. Apparently it is safer for them in the Netherlands than in England, though if that’s the case, Samuel wonders why his father is so occupied fighting there. But these brothers obviously know of Samuel. And very soon someone will be arriving in England on their behalf, to gauge the efficacy of Dr Arcampora’s work.

‘Look at him, Tanner – staring out into space like he’s expecting to spy the Almighty winking back at him from behind a cloud.’

Finney, the taller lad with wide-set eyes that seem frozen in a permanent stare of puzzlement, sets down the three fishing rods he’s carried up the hill, brushes aside the shanks of brown hair that the wind has blown across his brow and turns to his friend. He’s the same age as Tanner Bell – sixteen – but he lacks the patience that stops Tanner’s rebelliousness from sometimes sinking into youthful minor cruelties. ‘I tell you truthfully, Tanner, if he has one of his falling spells up here, he can slither back to Cleevely on his belly like the little arseworm he is.’ Finney doesn’t find it easy, looking after Samuel Wylde.

‘Leave him to his thoughts,’ Tanner replies. ‘He’s not harming anyone.’

‘Jesu,’ says Finney despondently, ‘let me see Southwark and the playhouse again just once more before I die of boredom in this wilderness!’

‘I can usually tell when one of his fallings is on the way,’ says Tanner Bell. ‘He goes all hawk-eyed. At the moment he’s just enjoying the view. Trust me.’

Finney and Tanner Bell are looking at a young willow of a lad, about their own age. He’s tall, slightly stooped, with milky skin and wide eyes, and a mop of thin hair the colour of early corn. His neck looks all the thinner for the scarf wrapped around it. He wears a dun-coloured broadcloth coat, defence against the chill wind, and calf-high boots laced tight, to support his ankles on the walk.

‘But what if he has one of his fits up here – a bad one?’ asks Finney. ‘What if the Devil comes into him? Are you comfortable with that notion, Tanner: us, him and the Devil, all on our own out here on a hilltop?’

‘It’s happened before,’ says Tanner Bell with a shrug that tightens the mutton-leg sleeves of his ill-fitting brown worsted coat across his plump shoulders. ‘It’s scary at first, but you get used to it.’

Given that Finney has been paid in coin to be here, Tanner Bell considers himself the only true friend Samuel has. Probably has ever had. While Sir Joshua Wylde has spent much of the last sixteen years in Holland, fighting hand-to-hand with the Pope, Tanner had been his son’s companion at Havington Manor, where Samuel had been deposited into the care of his grandparents, Sir William and Lady Mercy Havington.

‘I don’t know how you bear it,’ Finney says dismissively. ‘I wouldn’t have come if I’d known the truth. Compared to this, the playhouse is like living in Elysium.’

‘We Bells have served the Havingtons for three generations,’ says Tanner indignantly. ‘They’ve been good to us – better than a fellow could expect from the quality.’

‘Marry! The quality will throw you out at the first fart! How d’you think I ended up in the playhouse?’

‘Not Sir William and Lady Mercy,’ protests Tanner. ‘When my father lost what was left of his wits, after Dorney died, Sir William did his best to look after him – right until the end.’

‘Who’s Dorney? Not another addle-pate the Havingtons took in?’

‘My older brother. This is his worsted coat I’m wearing.’

‘I wondered why it doesn’t fit you.’

Tanner’s impish face becomes suddenly serious. ‘Dorney was tall, and very thin – more like your build. But he was seven years older than me.’ He turns his back on Finney and sticks out his backside. ‘See that patch?’ he says over his shoulder.

‘Yes,’ says Finney, looking at the coat where it spreads in broad pleats over Tanner’s buttocks. A coarsely stitched square – of a quite different pedigree from the rest of the coat – betrays the hasty repair.

‘That’s where the Spanish ball struck – the one that killed him,’ Tanner says in an awed voice, as if the patch is a holy relic.

‘That must have hurt,’ observes Finney.

Tanner Bell straightens and turns to face Finney again. ‘They sent the coat to my father, afterwards – didn’t fit him, either.’

‘And that’s why your father lost his wits: because of a coat?’

‘The coat was the last straw,’ says Tanner, wondering if all young players are as dull in the wits as Finney. ‘You see, Porter – my father – had gone to the Netherlands with Sir William in ’71. But Porter Bell wasn’t much of a soldier. He got caught, daft bugger – spent months as a captive of the Spaniards. Dorney’s death – June ’87 it was – was the very end of him. It was like the Devil just gathered up what the Dons had left of him the first time around and threw them on the midden.’

‘So he’s dead, is he – your father?’ asks Finney in a comradely tone. ‘Mine, too. Hanged for thieving a purse.’ He shrugs at the fickleness of fortune. ‘Would have got away with it, too, if he hadn’t chosen to rob the only magistrate in all twenty-six wards of London what could sprint more than ten paces after lunch.’

‘He’s not dead,’ says Tanner indignantly. ‘He’s in Gravesend.’

‘Have you ever played Gravesend?’ asks Finney.

‘It’s where he came from.’

‘Oh.’

‘When he became too ungovernable to stay at Havington Manor, Sir William set him up there, as a waterman. Even bought him his own wherry. That’s the sort of man Sir William was. I suppose I should have gone with him, but…’ Tanner’s voice trails off as he remembers the drunken blows, and the slurred protestations of regret that always followed. ‘Well, there was Samuel to look after, and I was always treated more like family than servant.’

‘Well, Gravesend or Cleevely – I know where I’d rather be.’

‘The theatre?’ says Tanner, knowing a little of Finney’s former life. ‘It might sound exciting. But sleeping on planks, and starving whenever the Lord Mayor chooses to shut the playhouses? At least here you get a mattress and fresh pottage.’ The habitual cheeriness returns to his puppyish face. ‘So stop griping about Samuel and his fits. Pick up those rods. There’s trout to catch – when he’s ready.’

Finney looks at Samuel, kneeling in impenetrable contemplation on the grass, and then in the general direction of Cleevely House. ‘Alright, Tanner – let’s say you’re correct and Samuel isn’t possessed by the Devil when he has one of his fallings,’ he says, sounding unconvinced. ‘But now that Dr Arcampora has arrived, Samuel doesn’t have very far to crawl if he wants to be. Does he?’

The city Customs House, set back a little from the river to the east of Billingsgate, is built like a castle keep: a stern hexagonal tower on each corner, and a door like the entrance to a prison set menacingly into the façade on the right-hand side. Glancing at its dour brick face in the early-morning light as she hurries along the quayside the next morning, Bianca wonders why the English like to reward an honest merchant’s endeavours with such a forbidding welcome. She already knows the answer: because of seditious Catholic pamphlets secreted in sacks of ginger from the Indies; because of forbidden Masses hidden amongst bags of Baltic hemp; because of letters wrapped in oilcloth and hidden in casks of herring – letters from the continental Catholic seminaries to their agents in England.

She can spot the men from the High Court of Admiralty and the Privy Council searchers in the crowd, simply by the way they appear to have no employment except to scan the throng with suspicious eyes.

Bianca comes across the bridge infrequently now. She has little need to. She long ago whittled out the merchants who pass off crushed acorns and rowan berries as genuine spices from the Indies, and the purveyors of hoof-shavings who swear on their mother’s grave they’re selling real narwhal horn landed from the western ocean. Most of what she uses in her concoctions, distillations and infusions comes from the little patch of ground that is her physic garden, down by the river and known only to herself and Nicholas. The rest – the small measures of frankincense and fenugreek, the cerasee and cardamom – she gets in exchange for her balms and salves from those few importers she trusts.

Since she arrived in the city, little more than two years ago, she has noticed how London’s mood has changed. The people are not as tolerant to strangers as they once were. On the heels of the threatened Spanish invasion in ’88 has come a deepening wariness of foreigners. They are taxed more, stopped by the watchmen more often, railed against in church sermons and official proclamations. And although she has absorbed the peculiarities of her adopted country as best she can, Bianca – betrayed by her corona of richly dark hair and the warm hue of her skin as one who has grown up beneath the Veneto sun – stands out in a crowd like a falcon amongst a flock of seagulls.

But most of all she puts this hardening of attitude down to the fact that England’s queen is almost sixty. She could die soon, though even to suggest such a possibility in public is treason. Now people are beginning to consider the possibility that Philip of Spain – once married to Elizabeth’s half-sister Mary – may once again seek to claim his late wife’s dowry, this time by conquest rather than marriage.

On Bankside, none of this seems to matter so much. In the liberty of Southwark, where the Lord Mayor’s writ does not run, people appear much less concerned by matters of state and faith. The theatre, the bull- and bear-baiting pits, the stews and the taverns seem, to Bianca, a clearer echo of what England might once have been, before the new faith with all its godly rectitude got its hands on the rest of the land.

Her trip across the bridge today has a purely commercial motive. As foretold by Timothy, her taproom lad, the Sirena di Venezia has arrived, and Bianca is not about to let the Hanging Sword and other taverns along the wharves grab the profitable trade of thirty or more Venetian mariners with coin to spend – not when there’s the Jackdaw just a brief walk away on the other shore. Not when Bianca Merton can flash her vivid amber eyes and extol the attractions of Southwark fluently in her mother’s own tongue: Italian. She’s even brought with her a leather jug of her best knock-down to sway any doubters.

Making her way around the piles of shining Muscovy pelts, neat stands of ornate panelling from Saxony and ingots of Swedish iron, Bianca sees the Sirena lying a little way ahead. Just as Timothy had said, she’s the largest ship at the wharf: a fine four-masted carrack. Painted proudly on her high stern-castle is a winged lion: the emblem of Venice. On the quayside, a gang of stevedores is raising a rampart of sacks. Suddenly she hears someone calling to her in a clear, sharp voice that carries the dialect of the central Veneto.

‘In nome dei santi benedetti! Bianca!’

Turning, Bianca searches for a familiar face amongst the men clustered around the Customs House. And then she sees him, strutting towards her, head held high, all five feet three inches of him. A little Venetian cockerel of a man: Bruno Barrani, her cousin from Padua – champion of the Catholic faith, as handsome as Alexander.

Perhaps not Alexander, she concedes in the moment of recognition. The aquiline nose is softly blunted at the tip, robbing it of patrician force, and the delicately curled black moustache he wears above his bud-like lips – and which in Padua he sported like a knight’s banner – might be considered by some (especially the English) as a little preposterous. But still, he’s handsome enough. Clad almost entirely in black – black hose, black doublet, black half-cape – his only concessions to colour are the crimson-braided points securing his doublet and the gilt buckles on his shoes. Even his hair, worn extravagantly long, is black. Unnaturally so. Then she remembers: Bruno was always in the habit of applying a dye of sage and indigo to it. She feels the smile spread across her face like the heat from a good fire.

As he reaches her, Bruno bends a knee so extravagantly that she could be Caterina di Medici herself. One arm sweeps across his little body as if he intends to make her a gift of all London. He seizes her right hand to kiss, and she gets a glimpse of black doeskin gloves studded with gemstones – probably glass, knowing Bruno. He launches himself upon a tide of voluble reunion.

Bianca stops him with a laugh. ‘Cousin, peace! English, please! Speak English.’

He looks hurt. ‘English? Why English? Have you forgotten your mother tongue since you came here?’

‘No, of course I haven’t. But it’s better that way,’ she tells him, not wanting to hurt his pride. ‘When the English overhear someone speak in a foreign language, they think he’s trying to outsmart them at commerce or plotting their downfall.’