Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

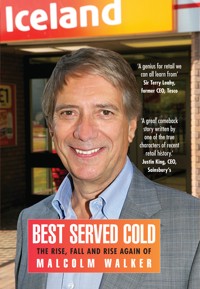

This is the dramatic story of the ups and downs of a born entrepreneur. Malcolm Walker was born in the West Riding of Yorkshire in 1946. With fellow Woolworth's trainee manager Peter Hinchcliffe, Walker opened a small frozen food shop called Iceland in the Shropshire town of Oswestry in 1970. Iceland became a public company 14 years later, through one of Britain's most successful stock exchange flotations of all time, and by 1999 it had grown into a £2 billion turnover business with 760 stores. In August 2000, Iceland merged with the Booker cash and carry business and Walker announced that he would step down as CEO in March 2001. In preparation for his retirement, he sold half his shares in the company and left for the holiday of a lifetime in the Maldives. However, while he was away the new management of the company slashed profit expectations, plunging Iceland into a £26m loss rather than the £130m profit the City had been expecting. Walker was fired and spent three years under investigation by the authorities before being cleared of any wrongdoing. In Walker's absence, Iceland's sales collapsed as customers deserted the company – and, almost exactly four years after he had left the business, he returned as its boss. His amazing revival of Iceland has seen like-for-like sales grow by more than 50% and the business winning the accolade of Best Big Company To Work For In the UK. In March 2012 Walker led a £1.5bn management buyout of the company and is now personally worth over £200m. The incredible story of Walker's life – which he tells here for the first time – is as dramatic as any you will find in business, and it serves as a model for how, through hard work and intelligent risk-taking, it is possible from a relatively modest upbringing to build a national enterprise and a household name known to millions.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 633

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

‘I have known Malcolm Walker for many years. His drive, tenacity and knowledge of his business remained with him throughout his turbulent period away from Iceland, and I was not remotely surprised by his great comeback. His story demonstrates that, regardless of any setback, if you know your business, care about your business and wake up every morning loving what you do, you have a great chance of making it a success. Well done, Malcolm.’

Sir Philip Green

(CEO, Arcadia Group)

‘Having competed with Iceland, and therefore Malcolm, throughout my retail career, the insight this book provides into what makes him tick would have been invaluable to me, had it been published twenty years ago! A great comeback story written by one of the true characters of recent retail history.’

Justin King

(CEO, Sainsbury’s)

‘An inspiring story and a cautionary tale. Malcolm Walker built Iceland into a household name but a botched merger and management succession threatened to undo a life’s work. They say “never go back” but Malcolm felt he had to in order to save the company and restore his reputation. Amazingly he succeeded and revealed a genius for retail we can all learn from.’

Sir Terry Leahy

(Former CEO, Tesco)

Malcolm Walker CBE

Founder, Chairman & Chief Executive, Iceland Foods Ltd

Malcolm Walker co-founded Iceland in 1970 and was its Chairman and Chief Executive through 30 years of continuous sales growth.

He left Iceland under a cloud early in 2001, but returned four years later to lead a transformation in its performance. Iceland today has sales of £2.6 billion, 800 stores and 25,000 employees, and is recognised as one of the Best Companies to Work For in the UK.

Malcolm has been married to Rhianydd for more than 40 years, and they have three grown-up children and eight grandchildren. Outside work, Malcolm’s greatest enthusiasms are for his home, garden and family, good food and wine, skiing, sailing and shooting.

Printed edition published in the UK in 2013 by

Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre,

39–41 North Road, London N7 9DP

email: [email protected]

www.iconbooks.net

This electronic edition published in 2013

by Icon Books Ltd

ISBN: 978-184831-701-7 (ePub format)

Text copyright © 2013 Malcolm Walker

The author has asserted his moral rights.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Typesetting by Marie Doherty

Contents

Title page

Quotes

Malcolm Walker

Copyright information

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Chapter 1: Prologue

Chapter 2: ‘You’re Fired!’

Chapter 3: The Strawberry Sellers

Chapter 4: A Multiple Retailer

Chapter 5: The Takeaway

Chapter 6: Moving up a Gear

Chapter 7: ‘Get it Bought’

Chapter 8: Another Day, Another Deal!

Chapter 9: Riding a Rocket

Chapter 10: ‘Let’s Go Hostile’

Chapter 11: Conquering the World

Chapter 12: Killing the Sacred Cows

Chapter 13: Losing Sleep

Chapter 14: Flying Again

Chapter 15: The New Millennium

Chapter 16: The Deal

Chapter 17: A Bad Start

Chapter 18: The Booker Prize for Fiction

Chapter 19: I’ve Got My Job Back

Chapter 20: The Share Sale

Chapter 21: Breaking and Entering

Chapter 22: Everything Hits the Fan!

Chapter 23: Animal Farm

Chapter 24: Starting Again

Chapter 25: The Vikings

Chapter 26: Full Circle

Chapter 27: Long-Term Greedy

Chapter 28: On Top of The World

Chapter 29: The Auction

Index

Plate section

To my wife Rhianydd, who has been my unstinting supporter since I was fifteen years old. She has given me the most amazing family and always allowed me the freedom to build the business, never complaining about the late nights or the many knocks we have had along the way.

It’s one of life’s ironies that enjoyment of our present success has been tempered by her illness, which has prompted our support for the work of Alzheimer’s Research UK.

Acknowledgements

A company is never built by one person. Iceland is the result of the combined effort, enthusiasm and in many cases the dedication of our staff. I would like to thank them all.

Particular thanks go to:

My wife and family for their support, encouragement and understanding; Peter Hinchcliffe for 25 years of partnership in the business; Bill and Norman Woodward for being our early mentors; Nigel Woodward for 43 years of support and friendship; John McLachlan for his shrewd investment; Geoff Mason and Barry Owen for taking me under their wings; Peter Bullivant for his friendship and advice; Tarsem Dhaliwal for his loyalty, support and constant encouragement; Nigel Broadhurst and Nick Canning for running the company and letting me feel I’m still in charge; Andy Pritchard for sharing the Dark Ages and Cooltrader; Kathy Wight for running my life so loyally and efficiently; Jon Asgeir Johannesson and Gunnar Sigurdsson for believing in me; Larus Welding for lending us the money in 2005, and for his guidance through Icelandic politics; Steven Walker for his friendship and for pushing me to do the deal; Russell Edey for protecting us from ourselves; Majid Ishaq for masterminding the management buyback in 2012; Dan Yealland for his advice and friendship in the brief time I knew him. I miss him; Keith Hann for all his help and advice; Peter Pugh for publishing this book; Bill Grimsey for giving me the opportunity to have a second career. And everyone else who has helped and encouraged me in my adventures, in business and elsewhere.

1

Prologue

‘Happy birthday, Ranny.’ Rhianydd looked at Debbie, and the two of them started crying again. It was 30 January 2001 and we were in the bar at the Four Seasons Hotel in London. Andy Pritchard and I raised our glasses and glanced at each other without embarrassment.

My mobile phone rang. The Four Seasons is a business hotel so there were no hostile looks from the staff. John Berry, our Company Secretary, was calling from his room upstairs. He said he was going to have room service and wouldn’t be joining us for dinner and please would I understand how difficult it was for him. ‘Christ almighty, what’s his problem?’ I thought aloud. I’d taken the guy on eighteen years ago and had seen him every day since.

‘Aren’t you even going to have a drink with us? It’s Ranny’s birthday.’

‘No, I can’t,’ he said. ‘But I think it will be OK to bump into you at breakfast.’

‘Bloody wimp,’ I mumbled.

Apparently the two Bills, Grimsey and Hoskins, were making a point of staying in some cheap hotel and had already told John that this would be the last time he would be staying at the Four Seasons. I suppose he had conflicting emotions. I’m sure he felt a great loyalty or maybe just sympathy for me, but he had the rest of his career to think of. Already Andy and I were bad news in the new Iceland regime. We finished the champagne and moved into the dining room.

I couldn’t decide how I felt. On the one hand there was great relief at being out of the company, which I’d been trying to achieve for the past two years but, on the other, bewilderment and even anger at how it had happened. Ranny was in emotional turmoil. I kept reminding her of our son Richard’s words the night before: ‘Don’t worry about it,’ he said, ‘happy endings only happen in fairy tales!’

Debbie was worried for different reasons: how were they going to make a living? What were Andy’s chances of ever getting another top job after this?

Although I stayed in the Four Seasons whenever I was in London, I never ate there. The food was too fussy for my liking and the meal always took too long. Tonight was different. It was certainly going to be a memorable occasion. It was also the last meal on expenses and Andy, ever the wine connoisseur, decided to sting the Bills for a couple of bottles of Palmer ’86.

Throughout the evening we kept churning it all over. ‘I’ve only had two jobs and I’ve been fired from them both!’ I thought this was a great line but the girls kept asking how it could happen and why we hadn’t stopped it.

‘Because I couldn’t,’ said Andy.

‘Because I didn’t want to,’ I said, more than once.

‘But it’s your company, you started it, you are Iceland,’ the girls reminded me.

‘Ranny, Grimsey is welcome to it,’ I said.

The press had been horrific over the past week and I knew over the next couple of days it would get a lot worse. That made it impossible for any of us to draw a line under things. Not unnaturally, the girls thought about their friends and their Mums and what people would think. For myself, I had got used to the idea over the past week and persuaded myself I didn’t care.

The board meeting had lasted until lunchtime; nineteen people around a long table at our lawyer Herbert Smith’s offices. Iceland directors, advisers and professionals – friends, too, I thought, but impotent while the charade was played out. Some of the advisers were already negotiating with their own consciences about where their loyalties lay and where their continuing fees would come from. I just wanted to get it over with. It would have been ludicrous for me to try to take the meeting as Chairman, so I handed over to David Price, our senior non-executive director.

David did a good job in trying to give Andy a fair hearing, even though Bill Grimsey didn’t want Andy to present papers to defend himself. I made a short speech first and then said that, much as I wanted to, I didn’t propose to resign unless the board asked me to. Edward Walker-Arnott, the much respected and now retired senior partner of Herbert Smith, had advised me not to resign when I consulted him privately, as a friend, three days earlier. ‘It will look as if you have done something wrong. Under no circumstances should you resign for at least a couple of months,’ he had told me. At the lunchtime break the non-executives did ask me to resign, so I was delighted to oblige. Andy and I both resigned as directors of the company but not as employees. We all agreed we should stay on the payroll until March to give us time to decide on our respective positions. I asked David Price if he would take over as Chairman and he said he would, but only until a permanent replacement could be found.

My recent share sale had now become a potential issue. Before my resignation, Tim Steadman of Herbert Smith agreed that I had followed the correct procedure, but had said that in view of all the bad press an investigation by the United Kingdom Listing Authority (UKLA) was almost inevitable. He also said there wouldn’t be any conflict in his firm advising me personally despite their connection with Iceland. I couldn’t get used to that idea as I had first used them in 1984 and felt that they worked for me. After lunch, Tim suggested I should spend some time with Stephen Gate, their compliance expert, and review all the events around my share sale. Gate worried me. I explained to him how I had telephoned each non-executive director in turn and asked their permission to sell shares.

I’d also asked several of our advisers and no one had had a problem.

‘What did you say when you spoke to the non-execs?’ he asked.

‘Well, I said I wanted to sell some shares and was that OK?’

‘Yes, but what were your exact words, what exactly did you say?’

‘I can’t remember but I asked their permission to sell and asked if they had any problems with that, and they didn’t. David Price even remarked that shares weren’t family heirlooms to be kept for ever.’ I was certain I had followed the correct procedure. I couldn’t understand what he was getting at.

The red wine was relaxing me as I repeated the conversation. ‘That guy is not on this planet. You won’t believe what he said next. He said, “When you asked the non-execs for permission to sell, did you say, ‘I am ringing pursuant to paragraph 5 (a) of the model code for share dealing to formally request permission to sell shares in the company’?”’

‘Are you serious?’ I said. ‘Nobody speaks like that. I know these guys well and would never use language that formal.’

‘Well, you should have,’ he insisted.

‘People like him probably do talk like that,’ said Andy.

The conversation with Gate had gone on for hours and, although he was supposed to be advising me, I felt his line of questioning was increasingly hostile. I was totally exhausted.

I saw Grimsey briefly at about 6.30pm and told him I would clear my office by the weekend. He expressed no regret at what had happened. I told him he had got everything he wanted now and asked him to play fair by Andy with his pay-off. ‘Don’t ask me to do anything that would jeopardise the interests of the shareholders’ was his only response. I had heard this line so many times over the past few weeks that it held no credibility for me. He reminded me of some kind of religious zealot preaching high-minded religion and burning people at the stake at the same time.

The four of us met for breakfast next morning and John Berry came over to talk to us but sat at a separate table. For the first time in 30 years there seemed to be no urgency to get on with the day. A great weight had been lifted off my shoulders only to be replaced by uncertainty. I signed the hotel bill but decided to pay for the wine and champagne personally. I didn’t want to give Grimsey an excuse to make an issue out of it.

Harnish met us in the hotel lobby. As our London chauffeur he always heard enough of what was said in the back of the car to work out what was going on. He looked bleak and visibly upset. He drove us to Northolt airport and gave everyone a tearful hug as we boarded the plane. That upset Ranny. He’d worked for us for years and been privy to many of our adventures.

It takes only 35 minutes for the Citation jet to get to Chester airport and this was of course the last time we’d be using it. We’d had a company plane for sixteen years and this had been our first brand new one, bought in 1995. It was still immaculate. We’d always made a profit on selling them and while company planes are often considered an emotive issue, I’d long since given up caring what people thought about it. As a national retailer we’d always found it an invaluable business tool and I’d defend it to anybody. I couldn’t imagine Grimsey keeping anything as extravagant, though. My lifestyle was going to change dramatically now but I couldn’t have been happier about it.

Kathy Wight, my PA, had packed 30 years of personal files into boxes and wrapped up all the accumulated clutter in my office. She’d organised a Transit van to be there the following Saturday morning to take the stuff home. The office was deserted but Janet Marsden, our Personnel Director, was there. I’d employed her twenty years ago as the youngest member of our team. She was obviously embarrassed and upset to be there. Grimsey had asked her to watch me take my possessions out of my office and ensure I didn’t nick any company papers. She said if I took any company documents she was required to make a list of them, but then she offered to go to her office and wait until I’d gone.

Andy was packing up at the same time but he had a lot less junk than me. I’d tended to keep a lot of my personal files at the office. So many adventures over 30 years had generated a lot of memories. We had a librarian who worked four hours each week keeping the archives and all the memorabilia and old photographs carefully filed. A few years earlier I’d realised that most of that kind of stuff had vanished over time and we’d decided to conserve what was left and also keep current items of interest for the future. I left it all behind without much thought.

We’d built a company from nothing to annual sales of over £5 billion. We employed over 30,000 people and probably as many again among our suppliers and support companies. We’d paid hundreds of millions to shareholders and at least £10 million to charity and made many people very wealthy, including some of our staff.

Then the letters and emails started to arrive from friends and colleagues in the business and I had plenty of time to reflect over the next few weeks about how it all began …

2

‘You’re Fired!’

A.V. Green was God. At least to Woolworth’s trainee managers he was. I’d been in his office only once before when I was promoted to deputy manager of Woolworth’s Wrexham branch. It was the biggest office I’d ever seen, dark and wood-panelled with his massive desk in one corner. It was certainly impressive. Last time it had been a handshake and a word of congratulations: the motivation factor of ten minutes with God was deemed to be worth a day out of the store with petrol expenses for the drive to the regional office in Dudley, Birmingham. Head office in London was something too important and remote for me even to contemplate. This time my visit was to get fired. It apparently didn’t occur to anyone to wonder why Johnnie Walton, the Wrexham store manager, couldn’t do it. Deputy store managers were important in the hierarchy and firing one was an event that required some drama.

Peter Hinchcliffe and I drove down to Birmingham together. Peter was called into Green’s office first and I had to wait in the corridor outside. It was only five minutes before it was my turn and I was given a speech about wasting an opportunity. I told Green that the company owed me about 10,000 hours in unpaid overtime but he didn’t seem impressed. His parting words to me were: ‘So, go and run your fish and chip shop or whatever it is.’ It was 27 January 1971, almost 30 years to the day before I was fired for the second time.

We drove back to Oswestry. Peter was deputy manager of Woolies there and that was where we had opened our first Iceland store three months earlier. We were both earning £26 per week at Woolies but our dismissal package had included our holiday pay and pension money so we figured we could last the next few months without drawing anything from the new business. I’d worked at Woolworth’s for seven years, the only job I’d had since leaving school, but I was glad to be out of it. I was bored and I wasn’t doing very well in the company. I was a little scared about the future but also excited: I was 24 and ready to make my fortune.

I joined Woolworth’s after a conversation with the careers teacher at school.

‘What are you good at?’ she asked me, obviously knowing it wasn’t academic studies.

‘I like organising things,’ I replied.

‘In that case you should go into retailing,’ she said. So I did.

I was born in 1946 and brought up in a mining village called Grange Moor in the West Riding of Yorkshire. My Dad was a colliery electrician but he was also something of an entrepreneur. He ran a smallholding of eight-and-a-half acres in his spare time. He grew vegetables and also kept poultry. He was one of the first to install the new battery cages, which were rapidly improving egg production at the time. I used to help him on the farm and like to think I developed my work ethic from him in those early days. In 1955 Dad had an accident at the pit when a coal-cutter crushed his foot, and he then went full-time on the poultry farm. Eventually he set up a small grocery shop near Huddersfield with my Mam and sold a lot of home-grown products and the sponge cakes Mam baked at home. He died young at 52, from cancer, when I was fourteen.

Although I failed the eleven-plus and went to a secondary modern school, I eventually got into grammar school as a late entrant in the second year. I still didn’t do very well: I managed four O-levels in four attempts. I was remembered at school for all the wrong reasons. I was always in trouble for some prank or other, and had also started going out with a very pretty girl in the fourth form called Rhianydd Jones. Rhianydd is a Welsh name, which Yorkshire kids could never hope to pronounce, so everybody called her Ranny. She was academic and something of a swot. The headmaster, Mr Faires, was anxious she shouldn’t be corrupted by my bad influence. Corporal punishment was a daily fact of life and I got the cane or the slipper more often than most. On one occasion Mr Faires had me in his study and counselled me to ‘keep away from Rhianydd’. ‘I’ll cool your ardour,’ he said, selecting a cane from his collection. At that moment we both noticed, through his window, the vicar walking down the school drive. He hesitated and said: ‘I think you should go now. I’ll deal with you later.’ I don’t think I’ve ever been so pleased to see a vicar.

I remember my last day at school. We had just finished our final assembly and sung ‘Lord dismiss us with thy blessing’. As we were filing out of the school hall I had a water pistol and squirted the maths teacher. His name was Evans and he had a minor speech impediment which caused him to end every sentence with ‘err’. We called him ‘Ker-man’. He dragged me out of the hall by my ear and gave me three strokes of the slipper. I must be a conformist at heart because I bent over when he told me to, even though I’d technically left school 60 seconds earlier.

Grange Moor was a pretty godforsaken place, and at night there was nothing to do except hang around the local village fish and chip shop. There were no youth clubs or anything like that. So I decided to liven things up by organising a dance in the local church hall. This was pretty ambitious stuff and involved three local bands. It was a really successful evening and all the proceeds went to Cancer Research. Flushed with success and my enhanced reputation in the village, I decided to organise another event where this time the proceeds would go to me. This was while I was still at school and I was soon running a small business organising dances at different venues in Huddersfield, booking some of the most popular live bands in the country at the time. All the commercial dance halls were already in use on Saturday nights, which only left church halls for me to book, but they were usually too small. Then I found St Patrick’s Hall in Huddersfield, which took 300 people. I ran a series of dances there, and one day I took a phone call from another small-time impresario called Peter Stringfellow (later of the famous London lap dancing club) who wanted to take over my venue. How different my life might have been if I’d gone into partnership with him.

I didn’t question my career teacher’s advice about going into retailing and applied to all the major chains: Littlewoods, Marks & Spencer and Lewis’s of Leeds. Littlewoods and Lewis’s turned me down because I failed their arithmetic test but the local M&S manager called me into his store to explain they only took graduates at 21 years of age. He offered me tea and spent a couple of hours telling me how to go about getting a job. He was really helpful and I realised then, in 1964, that M&S was a very special organisation.

I applied to Woolworth’s because I’d been told it wasn’t very difficult to get in – they took more or less anybody – but also because their store managers were by far the best paid in the business (they were paid a percentage of their store profits). In the 1960s Woolworth’s were at the tail end of 50 years of fantastic success and were the eighth largest company in the UK. Stories were legion about former managers and head office staff who had Rolls-Royces and chauffeurs. Those glory days were gone, but senior managers still did pretty well for themselves and the legend was enough to attract people like me. The catch, but also the incentive, was that absolutely everybody from the Chairman down had started at the bottom, sweeping the floors in the stockroom, and promotion was 100 per cent from within the company. Their selection process really took place during the job itself, which meant that the dropout rate was enormous.

I started working in the stockroom of the Huddersfield store at £6 for a six-day week. The stockroom manageress, Loui Maltis, was really butch and was always trying to prove she was ten times tougher than any man. She terrified me. The training programme was quite simple: there wasn’t one. You worked hard, tried to impress your boss, put in more hours than anybody else to prove how keen you were and, gradually, you worked your way up the ladder. You could go from the stockroom to the sales floor, through various positions of responsibility to store manager, area manager (or ‘superintendent’, as Woolies quaintly called the job, a real hangover from the past) and on until you made Chairman. At least that was the theory.

I worked in the stockroom at Huddersfield for two years. I swept the sales floor, stoked the old coke boilers twice a day and took my turn baling cardboard. If a child dropped an ice cream or a dog made a mess on the floor a shout would go down to the stockroom for someone, usually me, to come and clean it up. This tended to happen when my mates from school were in during their lunch hour from their ‘suit jobs’. ‘I’m a trainee manager, honest I am,’ I would tell them as I stood in my brown overall with a shovel and a brush in my hand. This was the real cutting edge of retail training.

I was still running my dances while at Woolies and I had also developed a new side-line in selling potatoes. Every spring, tons of seed potatoes would be delivered for the gardening counter. There were no garden centres to speak of then and the Woolies garden counter was big business. The potatoes came in hundredweight sacks, and I had to spend about three weeks in the store basement repacking and weighing them into seven-pound bags on an old kitchen scale. As the season came to an end we had about ten sacks (half a ton) left, which had to be dumped as the potatoes were already sprouting and it was getting too late to sell them. I asked the store manager if I could have them and he said I could. I organised a mate with a van to take them home, then paid a local farmer to plough our field so I could plant them. That October I employed kids in the village to harvest about ten tons of potatoes, which I sold back to Woolies for their canteen. Every morning I had to walk a mile to get the bus to Huddersfield and for weeks I did this carrying a sack of potatoes. I seem to remember I was paid about ten shillings (50 pence) for each half-hundredweight sack.

After two years in the stockroom I became worried about my lack of progress. The store’s deputy manager, Dan Gillette, who gave me the job, had moved on and a new deputy was in place. Dan had employed me as a ‘trainee manager’ but had forgotten to tell anybody. The store manager was Arnold Ravenhill, an alcoholic of the old school, always immaculately groomed and held in high regard by the company. He would spend most of each afternoon locked in the Horse and Jockey across from the loading bay door. He was a decent man but not easily approachable. I think he was also scared of Loui Maltis. One day I plucked up the courage to ask him about my career. He didn’t know I was a trainee. I felt my world had ended and I’d wasted any chance of a future.

Within a week or two I’d been offered a chance to prove my worth. I was asked to go to Heckmondwyke, a small town near Huddersfield, to a store where they were short-staffed in the stockroom. I remember arguing politics in the staff canteen with the girls in the store. Harold Wilson was the man of the moment but the real novelty was being in a mixed-sex canteen. Woolworth’s had a canteen in every store and provided a cooked breakfast and lunch. In most stores they had a separate canteen for stockroom males, who weren’t allowed to eat with management or female staff. But given that the store manager and I were the only men in the store it made sense even to Woolies to have just one dining room!

I must have done a good job in Heckmondwyke because soon after I was promoted to ‘junior’ trainee manager on the sales floor and moved to Leeds 5. This was one of the biggest stores in the country and the fifth store that Frank Winfield Woolworth had opened when he came to the UK from America. Charlie Beck, who was famous throughout the company, managed Leeds 5. Even though he was ‘only’ a store manager his status was considered to be higher than that of area managers and even ‘merchandise managers’, who were distant figures from head office in London second in importance only to buyers, the true aristocrats of the company. Charlie had an office like the bridge on a ship overlooking the ground sales floor (there were three sales floors in Leeds) and he was reputed to earn £12,000 per year. In 1965 that was a fortune – the equivalent of £300,000 in today’s money. Merchandise managers and buyers occasionally visited the store and arrived in their Jaguars and Humber Super Snipes; the young trainees, including me, got to drive them to the car park. Charlie, though, drove a van. He was near retirement and considered an eccentric, but devoted to the company. He worked six days a week, often came in on Sunday, and never took holidays. You could always tell when he was supposed to be on holiday or having a day off because he wore suede shoes to work. His van was for customer deliveries, which trainees did after the store had closed. This was Charlie’s idea, unheard of anywhere else in the company, but he would try anything to help sales.

I often drove Charlie’s van on deliveries but I also had my own Mini van, which was sometimes commandeered for deliveries too. Every Friday evening, on my way home, I had to deliver six cases of cat food to an old lady who lived on the outskirts of Leeds with a houseful of cats. One night she met me in tears. She had to move out of the house so the cats had to be put down: please would I take them to the vet next Friday when I called? A week later I arrived and she loaded a couple of cardboard boxes full of cats into the back of my Mini van. Goodness knows how many there were but apparently they weren’t all boxed up and she kept finding the odd cat and shoving it into my van. The cats weren’t at all impressed with this and there was a great deal of hissing and scratching going on. It was a nightmare straight out of an Alfred Hitchcock film. As I drove through Leeds to the vet, more and more cats escaped from the boxes and rocketed around the van. The cats were wild and I was shaken and bleeding when I reached my destination. As I got out of the van two or three cats streaked out of the door, never to be seen again. The vet came out carrying a long pole with a noose on the end, opened the van door a crack and fished inside until he caught one. I reckon he caught about half and the others escaped to become town cats.

Charlie took quite a shine to me and I had eighteen wonderful months working in that store. He had a sense of mischief, and one morning I caught him filling the lock of the shop next door with glue. The owner had upset him by complaining about one of his products. There were about twelve trainee managers in the Leeds store, an assistant manager and a deputy manager called Sherwood who had the most amazing halitosis. Trainees were graded as junior man, advanced man, ready man and then deputy manager. It was odd even then to have the job title ‘ready man’. Everyone dressed smartly in dark suits and most trainees wore detachable collars on their white shirts. Even in 1965 collarless shirts were becoming hard to find, but Marks & Spencer still sold them and Woolworth’s had a line in disposable stiff paper collars, which we thought looked really good. They could be reversed when they got dirty.

I soon learned the culture of the business. Trainees were almost encouraged to be arrogant because ‘Woolworth’, as we all called it without the ‘s’, was considered the only professional retail business in the country. Any other company was regarded as ‘Mickey Mouse’. I remember one store manager observing in all seriousness that he could run Marks & Spencer in his lunch hour. Every store had four coloured lights at a high level on the sales floor and each trainee was called to the telephone by a different combination. We were addressed by our surnames, and I was told to answer the phone as ‘Walker’. It was considered presumptuous to put ‘Mr’ before your name and first names were never used.

My first departments were crockery and glassware. I was responsible for displays, the ordering of stock and managing the staff. Technically I was in charge of the crockery supervisor who had been there for 40 years but you can imagine how she took to a nineteen-year-old trying to tell her what to do. Any store manager would rather lose a trainee than an old hand who knew the business inside out. That was obvious to me and obvious to the crockery supervisor. In that situation you learned pretty quickly how to get the best out of people.

I had had to leave home when I started work in Leeds. In Grange Moor if you didn’t go to university, and nobody did, you lived with your parents until you got married. Woolworth’s was my university. I lived in a flat with two other trainees and learned to cope with the launderette, a little cooking, late nights and a lot of drinking. Work started at 8am, or 7am if it was your turn to let in the bread man, and you never finished before 9pm – sometimes 10pm. If you took a day off you were considered not to be ‘keen’.

One of my first surprises in Leeds was that every product had two prices. The correct ‘list price’ ticket was put into the ticket holder and then an inflated price was displayed on another ticket placed over the top. Customers were charged the higher price, which was what you thought you could get for the product, but if a head office visitor came into the store the top price tickets would be quickly whipped off so that he saw only the official price. As soon as he’d gone the other tickets would be put back. The idea was that the extra money would cover ‘shrinkage’: stock loss caused by breakage or pilfering or by having to cut prices to clear old stock. It’s not possible to run any retail business without shrinkage, but a good manager will minimise it, while a bad manager might let it get out of control. Controlling shrinkage seemed to be the only thing that mattered at Woolworth’s and managers got up to all kinds of tricks, not just to control it, but to cover it by generating extra money which wasn’t accounted for in the book-keeping system.

I don’t know how it happened but perhaps one careless manager once generated more money than he lost through shrinkage so that, after the year-end stock-take his store showed a stock ‘overage’. That is not possible in a properly run store but the extra profit must have been appreciated because instead of being fired the manager was promoted. However it started, the bizarre situation existed throughout the company that managers were promoted for overages and fired for showing any shrinkage. The bigger the overage the better. This encouraged all kinds of ‘fiddles’ as managers inflated prices and became ever more inventive in finding ways to generate cash outside the system to hide shrinkage.

Charlie even had a spare cash register on the sales floor. The money taken through that till was not recorded in the books but collected separately, then used for buying stock for cash, which was sold in store. Since there was no record of the transaction in the books the profit on the product covered shrinkage. You could only sell official Woolworth’s merchandise but several suppliers cooperated with Charlie in selling to him for cash instead of through the official ordering system. His van was useful for supplier collections as well as customer deliveries. This crazy situation existed throughout my seven years with Woolworth’s. You had to fiddle the system to create an overage and gain promotion but you would be fired if you were caught doing it! If you showed even a small shrinkage – which, if you played it straight, you couldn’t avoid – you also got fired.

Trainee managers were moved periodically to another store in the region, usually at a week’s notice. I was promoted to ‘advanced man’ at a salary of £15 per week and moved to Scarborough on 8 May 1967. The prospect of doing a summer season at Scarborough was exciting and I enjoyed my time there. Typically you left your old store on a Saturday night and the company would generously pay only your first night’s accommodation at a hotel in your new town. That tended to be on a Sunday night so that you could arrive at your new store at 8am on Monday morning, shoes polished and ready to go. At about 6pm on that first day you might ask your manager if it would be OK to slip off early and find somewhere to live. In practice trainees already in the store knew about flats or digs and you were usually invited to share so it was never really a problem, but the system certainly taught you to be self-reliant and resourceful.

After Scarborough I was moved to Lincoln, then on to Rhyl in North Wales where I was promoted to ‘ready man’ at a salary of £18 per week. Since the store wasn’t big enough to warrant a deputy manager, I was also the assistant manager.

It was usual to have a session in the pub when you left a store, and the party at Lincoln sticks in my memory. I was standing in the pub toilet a little the worse for wear and smoking a cigar, when a voice from next to me said: ‘That cigar stinks.’ I looked at the man who’d spoken. ‘You don’t recognise me, do you?’ he said. Then it dawned on me who he was and I went cold. I had to pretend I didn’t know him, which gave my friend a little time to slip away for help. Shoplifters were always a problem in Woolworth’s and I’d caught this guy some months earlier. I’d been a witness in court when he was sent to prison for six months. He was a big bloke and out for revenge, but luckily he’d only half strangled me before the cavalry arrived to rescue me.

I drove home to Yorkshire the following evening before going on to Rhyl the next day. I managed to crash my Mini van five miles from home so I arrived in Rhyl by train on a cold, foggy, miserable night on 13 October 1968. I thought it was the most godforsaken place on earth.

Tony Coyle was the Rhyl store manager: a tall, energetic, ambitious man with jet-black curly hair. He was desperate for promotion. On my first morning he took me into his tiny office to explain how he saw things. He was going to go far in the company, of that he had no doubt, and nobody would stand in his way. I could go with him, which meant doing things his way and specifically delivering the biggest overage the company had ever seen, or … well, the alternative wasn’t even to be contemplated. I hastily assured him of my commitment and enthusiasm and promised my support. I liked Tony but he wasn’t generally well liked by other managers. Even in a company where ambition and enthusiasm were everything he was considered really over the top. Tony’s speciality was cost control. Woolworth’s managers generally felt they couldn’t influence the sales line: poor sales were considered the fault of buyers not delivering the right products. You had to do what you could, of course, but managers could more directly influence the profits of the store and their own pay packet by controlling costs.

Tony believed he wouldn’t spend more than two years in Rhyl before being promoted so the problems he was going to leave behind would be left for someone else to sort out. He had a simplistic attitude to cost control. You could cut the store electricity bill by switching off lights, so he kept the sales floor on half lighting throughout the quiet winter months. The problem was, he cut his electricity bill for the first year but it couldn’t be allowed to rise again in the second, so the store had to go on quarter lighting. The third year was going to be someone else’s problem. This philosophy extended across all areas of overhead. In most retail companies it would be a crime to run out of paper bags but Tony encouraged staff to persuade customers that they didn’t need bags. Nothing in the store was ever repaired, nothing was painted and if a customer brought a faulty product back, under no circumstances could you give them a refund. ‘Tell them you’ll send it back to the manufacturers,’ he’d say, ‘and the next time they come in, tell them you’ve not heard anything. They’ll soon get fed up.’ Attitudes like this contributed to the decline of the company, but the system encouraged it and, to a lesser extent, similar practices were widespread. Tony’s obsession with cost control even extended to his private life. Every day he drove to work in the green Zephyr Six that was his pride and joy, and he always told us on arrival how far he’d got without switching on his lights during the dark winter mornings. One day, on the drive in to work, a golf ball landed on his bonnet and dented it. He was distraught.

In many ways Tony was a good manager. He spent time with his trainees every evening when we all had to tell him how much ‘shrinkage cover’ we had made that day. He made us all feel part of a team. He was misguided but he could motivate. He trusted no one. I learned a lot about shrinkage control from him. Everyone, he said, was trying to rip us off. ‘Back door shrinkage’ is a term in retailing that refers to the stock you lose or is short delivered by suppliers at the loading bay. Tony lost not one penny. However, he did have one big fault as far as I was concerned: he insisted that when the store was open all I did was ‘watch service’, that is make sure that staff were moved from one counter to another as it got busy. All other work had to be done after the store was closed so the hours I worked were phenomenal, but during the day I just walked round and round the store and was bored rigid.

I was still going out with Rhianydd and we were getting quite serious. She came to stay in Rhyl for a few weeks during her college holidays and although it was strictly against company rules for managers to go out with staff, Tony gave her a temporary job in the cash office. One day John Richards, the Superintendent (area manager) gave me a major bollocking for something I’d done wrong, which Ranny overheard. I really liked Richards, partly because you knew where you stood with him. He didn’t harbour grudges but could give you a serious telling off and then wink at you, just to let you know it was immediately forgotten. Ranny was incredulous at how one human being could speak to another in that way. You had to be thick-skinned to be a retailer.

At the start of the summer season a bloke who obviously knew Tony turned up at the store. He set up a ‘seaside’ backdrop at the front of the store and took your picture with a primitive Polaroid camera, then mounted it inside a plastic key ring. He charged five shillings (25 pence) for this and made a fortune. He paid rent for his pitch to Tony, which was one more way of covering shrinkage. This gave me an idea. I’d become friendly with Louis Parker, the son of one of the local amusement arcade tycoons. (Louis later opened a nightclub in Rhyl, which was a huge success, largely because he invented something called the ‘Miss Wet T Shirt Competition’.) I persuaded him to sell me a second hand candyfloss machine for £25.

A candyfloss machine is nothing more than a spinning drum with an electric heating element at the centre. A teaspoon full of ordinary sugar dropped on the hot element is whizzed out into candyfloss threads in seconds. A touch of cochineal dye on the sugar makes it red. All you do then is pick up a ball of it on a stick and you have converted a few grains of sugar into one shilling (five pence). I asked Tony if I could rent a space at the front of the store to sell candyfloss, to which he agreed. I employed a student for the summer holidays and had made enough money by the end of the season to buy Ranny a decent engagement ring.

We got married in October 1969 and for the grand sum of £25 each we took one of the first ever package tours and honeymooned in Ibiza. At the same time I was moved to Wrexham as deputy store manager and I agreed to rent a farm cottage nearby. I told Ranny about the outside toilet while we were on honeymoon but she thought I was joking – until we got back.

All I knew about Wrexham was that Arnold Ravenhill, my old boss from Huddersfield, had retired there. The Wrexham store was an old building with a wooden floor and was overrun with mice. They were eating everything and had defeated Rentokil. The trainees seemed to spend half their life catching mice. The only thing that worked was to smear glue into a circle on a piece of cardboard and put chocolate in the middle. We had to put several of these on the floor every night, and next morning dozens of mice would be stuck fast on each one, still alive.

Soon after I arrived, the store manager retired and a new manager, Johnnie Walton, was appointed. He was considered to be of the right calibre to oversee the move from the old Wrexham premises to a brand new flagship store up the street. It was probably the last megastore that Woolworth’s ever built. Johnnie Walton was one of the most objectionable men I have ever worked for. His favourite trick was reserved for when sales reps and other visitors came up to him on the sales floor. They would usually thrust out their hand to shake his in greeting. Walton was a big man with a large gut and he would draw himself up to his full height and look down at them as if they had crawled from under a stone, keeping his hands firmly behind his back. It was the ultimate put-down and I never understood why he did it.

I disliked Walton and he disliked me. His hobby was keeping parrots and he had me labouring for several weeks at his house building an aviary. Gradually I started to hate my job. I decided I would never make a successful career at Woolworth’s. I was working long hours at Wrexham, usually six days a week, and I also had to ‘check the store’ on Sundays. Since I still hadn’t replaced my crashed Mini van that meant I had to go in to work on the bus. On Sunday, when buses were less frequent, it meant if I jumped off the bus when it arrived at Wrexham bus station and ran like hell, I could check round the store and usually get back home on the same bus. If I missed it, the afternoon was gone. I began to wonder what on earth I was going to do with my life. I’d spent seven years at Woolworth’s, I couldn’t see a future and felt I’d wasted an important start to my career.

One day another trainee manager from the Oswestry store, Peter Hinchcliffe, came over to help in Wrexham and we had a drink together after work. We got on well and saw quite a bit of each other, usually in the pub where we would moan about our jobs and put the company to rights. Of course, next day in the store we were both too frightened to say anything. I told Peter about my dances and how I wanted my own business, and Peter told me about the ‘stamp club’ he used to run through various children’s comics. One Saturday night Ranny and I, with Peter and his girlfriend Jean, were going out for a drink in my newly acquired second hand Singer Vogue car. We drove past a strawberry seller at the side of the road. He was packing up, but on impulse we stopped and negotiated a discount price to buy all his remaining stock of about half a dozen boxes. The next morning we drove to the Horseshoe Pass, a local beauty spot, to resell them. Our business partnership had been born.

3

The Strawberry Sellers

Sex sells! That was our first lesson in marketing. We’d parked the car and arranged the boxes of strawberries in a nice display on the grass verge. We’d made a large sign displaying the price, which gave us a modest profit over what we’d paid, and propped it in front of the car. Then Peter, Ranny, Jean and I sat down to wait for customers. An hour later we hadn’t sold a single punnet. It was at that moment I had an idea: Peter and I hid behind the wall and within minutes cars were stopping. The girls did a roaring trade and soon sold out. We packed up and went to the pub to spend our profits and decide what to do next.

Over the next few weeks the four of us kept meeting for a drink or a meal, usually at our rented cottage, to discuss various hare-brained business ideas and moan about Woolworth’s. One day Peter turned up quite excited and showed me a chain letter he had just bought from a friend for £1. He was convinced he was going to make a lot of money out of it and did I want to buy one? He had three to sell. The idea was that you bought a letter, then sent £1 to the organiser of the chain and also returned a list, which came with the letter, with the names of eight people who had bought letters previously, having added your own name and address to the bottom of the list. You sent £1 to the person at the top of the list and the organiser sent you back three new letters and lists with your own name moved up a notch. You had to sell these three new letters for £1 each, so you got your money back. Then you waited for the chain to spread and your own name to move up the list. Eventually thousands of people would be sending you £1 postal orders.

That was the theory anyway but I couldn’t see this working and thought the chain was bound to fizzle out. I said to Peter, ‘The only person making money out of this is the organiser. Why don’t we start one ourselves?’ We soon convinced ourselves this was the quickest way to make our fortune and set about organising everything. We decided on a name that we thought would lend gravitas to our new business: ‘Investors Services’. We rented an accommodation address in Liverpool to have our mail delivered, and printed thousands of the letters we’d need, which explained everything. We also acquired an old typewriter, as everyone sending in their £1 postal orders would need the list of addresses retyping, leaving off the one at the top and adding theirs to the bottom.

The problem was starting the chain, so we typed a list of friends’ names and addresses and added ourselves to the bottom so we could then sell the list claiming we’d bought it ourselves. Of course, we should only have sold three but we sold dozens to get the chain going and I really believed we were about to become rich. Soon postal orders started to arrive and we retyped the lists and sent them back. The people we’d put at the top of the list would wonder what on earth had happened when they started to receive postal orders out of the blue! I soon lost all interest in Woolworth’s as I was convinced this was going to work. At first we thought it was quite funny when someone to whom we had sold a letter sent in their £1, and when we asked them if they had sold on their three letters they said they had, but we soon knew they hadn’t because the letters didn’t come back to Investors Services. That was the flaw in the system: many people found it difficult to sell letters on and the chain fizzled out quite quickly.

It didn’t worry us though because Peter had found a new product that would make us even more money, and not in such a dodgy area as ‘financial services’. He was an avid reader of Exchange and Mart and had seen an advert for ‘Superflon’. This was an aerosol spray can that contained some magic fluid that gave aluminium pans a non-stick coating. Non-stick pans were still quite new and expensive and we thought the opportunity for people to make their existing pans non-stick would be in great demand. We decided the best way to sell these aerosols, which were quite expensive, was to demonstrate them at ‘non-stick parties’. Tupperware was going great guns and we saw this as a similar opportunity for people to earn money by becoming ‘non-stick agents’. We ordered twenty cases of Superflon and Peter’s girlfriend Jean organised the first party in Oswestry, but by then we’d already moved on again. We had decided that if we were ever going to leave Woolworth’s we should set up a proper business and stop messing about.

We decided to open a shop. The problem was, what should we sell? We had no money so we couldn’t afford any type of business that required even a modest stockholding. A shoe shop, for example, would need shoes of every size, colour and style sitting on the shelves before you could open the doors. The same was true of most retail sectors. Woolworth’s had departments that sold glassware and gardening, crockery and confectionery, hardware and hosiery; in fact most things you could think of. We knew a little about most departments but not a lot about any of them. The only product we could think of where you didn’t need to carry much stockholding was fruit and vegetables. You had it delivered every day and sold it every day. We knew the suppliers from Woolworth’s and figured we could set up a shop without any money. Provided we could get a week’s credit from our suppliers we would always have a week’s sales in the bank before we had to pay anybody.

Peter said he knew where there was an empty shop to rent in Oswestry, next door to the Queen’s Hotel. We found out the landlord was Border Breweries in Wrexham so I went to see if we could do a deal. The shop was available to rent at £15 per week on a three-year lease, and we thought we should offer to take it, provided they allowed us a ‘get out’ clause after three months. This would provide us with some degree of safety if our project didn’t succeed. We didn’t plan to let Woolworth’s know what we were doing and thought if we could keep it a secret for a few weeks, until we were sure it would work, then we had the option of carrying on with our careers if it didn’t work out. We found a young solicitor, John Evans, and asked him to draw up a partnership agreement and finalise the lease terms with Border Breweries.

When I worked at Leeds 5, the Superintendent would occasionally ask all the trainees to go out in their lunch hour and come back with twelve ideas for new products to sell. He had to attend a regional meeting with the buyers and needed us to feed him with ideas. New products aren’t that easy to find and usually ideas were for range extension with increased pack sizes or variations on what we already sold. On one such foray, I was looking round Lewis’s department store and saw that they were selling ‘loose’ frozen foods. They had an open top freezer, crusted with ice and with plastic washing up bowls in the bottom full of frozen vegetables. These were scooped into plastic bags and sold by weight. I put the idea on my list of suggestions but I never heard anything back. In Wrexham more recently I had noticed a shop that specialised in loose frozen food called ‘The Ice Box’. There were always queues outside its door. Few people owned a freezer at that time and supermarkets only had small frozen food cabinets with a limited range of Birds Eye and Findus products, which were nearly all sold in eight-ounce packets. Loose frozen foods were considerably cheaper as there was no packaging involved and you could buy just the quantities you wanted. I suggested we should sell loose frozen foods in our shop.