Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

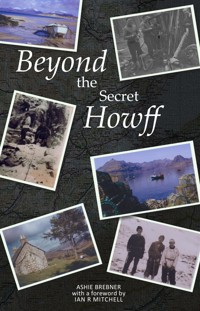

As a young man with a compelling interest in the great outdoors and the natural world Allister ('Ashie') Brebner spent his precious weekends in the 1950s and early '60s as a pioneer of the emerging Scottish bothying and mountaineering scene, and was one of the builders of the famed Secret Howff on Bheinn a' Bhuird in the Cairngorms. At the start of the 1960s he threw in his steady, well-paid job as a factory worker and, with another companion who did the same, started as a pioneer of mountain and nature guiding in the Scottish Highlands. Here is the unique story of a working man whose odyssey took him from the tenements and factory work of Aberdeen to the mountains and islands of the Highlands, their people and their wildlife.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 409

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ALLISTER (‘ASHIE’) BREBNER was born in 1935 in a working class tenement near Pittodrie Stadium in Aberdeen. He left school at 15 and trained as a motor vehicle mechanic, later working as a maintenance engineer in Aberdeen’s paper industry. Participating in the explosion of outdoor activity after 1945, Ashie developed a deep love of the Scottish mountains and in 1963 gave up his job and co-founded Highland Safaris, a nature and outdoor guiding company, which he continued with until his retirement. Ashie lives in Strathpeffer, Ross-shire and this is his first book.

First published 2017

ISBN: 978-1-910745-87-8

The paper used in this book is recyclable. It is made from low chlorine pulps produced in a low energy, low emissions manner from renewable forests.

Printed and bound by

Bell & Bain Ltd., Glasgow

Typeset in 10.5 point Sabon

by 3btype.com

The authors’ right to be identified as author of this work under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

© Ashie Brebner 2017

For Norma, Derry and Bruce, who put up with my long absences every summer over many years.

Contents

Acknowledgements

Introduction by Ian R Mitchell

Preface: Tied to The Machine, Early Life in Aberdeen

CHAPTER ONE The Post-war Birth of Cairngorm Bothying

CHAPTER TWO Building the Secret Howff on Beinn a’ Bhuird

CHAPTER THREE Unsung Ski Mountaineering Pioneers

CHAPTER FOUR Transport Problems in the 1950s

CHAPTER FIVE Breaking Out: Choosing a Life in the Highlands

CHAPTER SIX From Ross-shire with Love

CHAPTER SEVEN Making Ends Meet: Winter Work

CHAPTER EIGHT Breakthrough: War Games at Cape Wrath

CHAPTER NINE Ski Explorations on Ben Wyvis

CHAPTER TEN Sandwood Bay Magic

CHAPTER ELEVEN Bird Islands: Handa and Mousa

CHAPTER TWELVE Exploring the Far North Coast

CHAPTER THIRTEEN Skye Highs Over the Years

CHAPTER FOURTEEN Boats and Boatmen: Island Travel in the 1960s

CHAPTER FIFTEEN The Outer Edge; Hebridean Adventures

CHAPTER SIXTEEN Flying High, Flying Free: Eagles

Epilogue: Full Circle: Return to the Secret Howff

Acknowledgements

I owe a great debt to Ian R Mitchell for his encouragement, constructive criticism and initial editing, without which this book would never have been written. But most of all, for the friendship which developed through our mutual love of the wild places of the Scottish Highlands.

Introduction

I HAD HEARD OF, or rather read of, Ashie long before I met him. In ‘Cairngorm Commentary’, my favourite chapter of the great Aberdonian mountaineer Tom Patey’s classic book, One Man’s Mountains, there was a reference to the various underbelly characters who frequented the Cairngorms in the 1950s – a full decade before I myself ventured there. Just as was the case later in the 1960s, everybody ten years before had had a nickname and here were, amongst many others, Chesty, Dizzie, Sticker… and Ashie. Patey had introduced me to Ashie, but in doing so had made an error; in the same chapter he ascribed the building of the Secret Howff on Beinn a’ Bhuird (which was a home from home for me in the 1960s) to another group of climbers, the Kincorth Club, whose leader-aff was one Freddy Malcolm.

I had inadvertently perpetuated Patey’s error, by repeating it in a chapter of the work I co-wrote with Dave Brown in the late 1980s, Mountain Days and Bothy Nights, and there the matter rested… until, after a further decade had passed, Ashie was given a copy of our book. He had already discovered that his howff still existed and was being maintained, and to put the matter straight he wrote to me with a full account of the construction of this ‘Eighth Wonder of the Cairngorms’ (Patey), which is reproduced in this current volume.

Ashie and I became good pals and met and communicated over the years many times, and collaborated on a number of radio and television programmes as well. Just a pity he is that bit ower auld tae keep up wi mi on the hills, or I am sure we would have also been mountaineering buddies. Seriously though, Ashie helped me in other ways, in addition to the finer points of Cairngorm mountaineering historiography, in that he was a great boon to my writing of the volume I published on our mutual home city, Aberdeen Beyond the Granite, by giving me fascinating information about the part of Aberdeen – its Grunnit Heart – where he grew up. I was thus more than willing to give Ashie a hand in turn by writing an Introduction to his book.

But again and again, it was more than that. Our whole generation of the 1960s owed so much to Ashie’s pioneering post-war mountaineering companions. They pioneered the climbing routes that were in the Guidebooks by the time we emerged, they wore down the resistance of the lairds and others who were hostile to the accessing of the hills – thus, by our day, though still there, that was a residual problem. And by using the houses of the gamekeepers, shepherds and others that were being abandoned from around 1940, they started the whole bothy tradition, which also ensured that by using them, the buildings were still there when the Mountain Bothies Association, like the Seventh Cavalry, came to their rescue from 1965 onwards.

Ashie’s tale is not unique; it is a part of the wider story of the discovery of the mountaineering outdoors by the working class of Scotland. It started first on Clydeside in the 1930s with the onset of the depression, and its tale is embodied in accounts of the lives of such people as Jock Nimlim, which has been told by IDS Thomson in May the Fire Always Be Lit. Aberdeen, up there in the Caul Shulder of the country was, as often, slower to respond, but in the aftermath of 1945, it caught up with seven league ex-Army boots. As Ashie says, the availability of cheap ex-Army gear was an essential element in facilitating the activities of young working men in the era of post war austerity. And these were days of broadening horizons: full employment and gradually increasing leisure time gave people opportunities for outdoor activities their Depression-hit parents could not have dreamed of. But Ashie and his peers were less fortunate than we – who came so shortly later – were in one way; they missed out on the phenomenal expansion of education, free education, that we had, and most of them had to remain in industrial or other employment. By the 1960s anyone with intelligence could do a couple of evening classes, go to university on a full grant with no fees – and no risk – jobs a plenty were a-waiting for graduates then. Almost all of the working class kids I went to the hills with in the 1960s were manual workers, like Ashie, often serving an apprenticeship. But all of them escaped from industrial wage slavery through university. Ashie’s generation? Some – like Freddy Malcolm – remained industrial workers, some, like Chesty and Sticker, emigrated to Canada and elsewhere, but only one, Ashie himself, took the road he did.

And taking that road took courage; he took a big risk, giving up a steady job in the Never Had It So Good era of the early 1960s, and heading off like a pioneer into a Highlands where no one offered, and no one had tried to offer, mountain guiding and nature guiding. Ashie had, the reader will see, a strong personality, and support from his life-partner. He is also a man of some skill: self-taught ski mountaineer, self-taught ornithologist. And, as I discovered when working through his manuscript, an excellent self-taught writer, a product of the days fan ye were learned richt at the squeel – and belted if you made mistakes!

Recently, by writing a couple of articles in journals and appearing on a number of radio and TV programmes, Ashie has become a kind of cult figure amongst the cognoscenti of the Scottish mountaineering world. The publication of Beyond the Secret Howff will bring a wider audience of contemporary mountaineers, skiers and naturalists to Allister Brebner’s engrossing tales of adventures in a Highlands far removed from today’s touristified mecca. Readers will enjoy his tales of early bothying and pioneering mountain skiing, of building the Secret Howff, and of his later experiences and adventures in the Highlands at a period that now seems very remote. Ashie has been able, within the limitations we all face, to live the kind of life he wanted to live. How many of us can say that?

I did, I suppose, inevitably, read these biographical essays with a certain nostalgia, but also with a sense of sadness. The social changes we have witnessed in society since, for the sake of argument, the 1980s, have meant that the world is not producing the Ashies and the Chestys and the Stickers any more, any more than it is producing the Fishgut Macs and Stumpys of my 1960s generation. The idea that someone from Ashie’s background could do today what he did then, is preposterous, as preposterous as is the idea that the housing estate in Aberdeen where I grew up could send, as it did in the 1960s, dozens of kids to university every year. Ashie ends his book by welcoming the expansion of outdoor activities and nature education and other factors that have brought countless thousands to experience the life of the Scottish mountains. Alas – though age can dim perspective as well as eyesight and hearing – these developments have brought with them a certain blandness. For that reason, as well as for its intrinsic qualities, I thoroughly recommend Ashie’s book to any reader interested in the Scottish outdoors.

Ian R Mitchell

PREFACE

Tied to The Machine: Early Life in Aberdeen

IT WAS SPRING 1963. The machinery clattered incessantly and the heat was oppressive as I stared dispiritedly out of the factory window. Surely there must be another way of making a living? I had been working here for six years now as a maintenance mechanic for the machines, which produced countless thousands of envelopes every day. I loathed it and felt trapped. There was a family tradition of working here. My three aunts had spent all their working lives in the factory. Their potential husbands had in all probability been killed in the First World War. My father, too, had resigned himself to a lifetime here. He had contracted rheumatic fever as a prisoner of war towards the end of the same conflict and, after six long years of unemployment, had been grateful for the opportunity of secure work. He was not at all eager that I should do the same.

I had served an apprenticeship as a motor mechanic, not for any great love of motor vehicles but because a job was available and there was nothing else worthwhile to do. It was usually the case that the garages at that time would employ several apprentices (for they were useful cheap labour) and then at the end of a five-year period, the apprentices’ employment would be terminated, usually when the winter came along. It may be difficult to believe now but most people who could afford a car in the early 1950s would lay up their car during the winter months, so with no repairs needed to cars, the garage was empty and the employer would pay off the fully fledged apprentices to save money – and you would have to look around for something else. Hence the reason for my employment in the envelope making factory.

This was Pirie Appleton’s works in central Aberdeen, just beside the Joint Station, and it employed about 500 workers at that time. Pirie’s had originally been a cotton mill, later it converted to the paper industry. It was crammed into a narrow location beside the station, and was a notable landmark in the town centre in the 1950s and ’60s, since on one gable wall there was a huge representation of a Scottie Dog as an advertising logo; the mill has long since closed and has been replaced by an ugly office block.

My first position in this job was to maintain all the pulleys, shafts and belts over six floors of clattering machines, which produced all shapes, sizes and qualities of envelope. There were on each floor approximately up to 160 machines in four rows of shafts ranged over the six floors. I was kitted out in a specially designed boiler suit which was very close fitting, especially around the sleeves and cuffs, for this was potentially a dangerous job. Since it was impossible to hear any sound other than the clatter of machinery, a coloured light would come on which would alert me to a problem on a particular floor. I would make my way to the trouble spot and find that a machine was giving trouble, and there a mechanic specialising in this type of machine would be waiting for me. Since he couldn’t work on it while the pulley and belt were still running off the main shaft, it was my job to throw the belt off the main driving shaft for the whole department. This way the machine could be isolated without the entire department of perhaps 160 machines being brought to a halt. This is where the specialised boiler suit came in, for I had to pull the belt off at the machine end to allow the mechanic to work safely, then climb atop the machine on completion of the work, to throw the belt back on to the spinning main pulley shaft, making sure I was on the right side of the fast spinning pulley, then throw the belt on quickly. If any part of my attire caught on the belts, then at least I would be thrown out. There had been many fatalities of people being dragged in by throwing the belt from the wrong side.

All these individual machines were operated by women. In fact, it was a major source of employment for women in Aberdeen and quite early on I discovered an anomaly and a puzzle which took me some time to work out. While waiting for the mechanic to finish a repair, I fell into conversation with the girl who operated it. I had heard that this girl had just got married, so I bawled out, ‘I hear ye got mairriet last week!’

She looked all around her in horror and said into my ear, ‘For God’s sake, dinna spikk about that in here! If the bosses hear aboot that, I’m oot the door!’

‘Foo is that then?’ I asked, mystified.

‘Because mairriet women are nae allowed tae work here,’ was the answer.

This greatly puzzled me at the time. It seemed a strange order from above for why would they prevent a potentially good worker from being employed simply because they were married? Then the answer came to me and was well illustrated in my own family. Far from being a diktat, it was an act of compassion. After two world wars, because there were so many single women whose potential husbands had been killed, it had been decided that single women would be given top priority of work, for in those days married women could expect a husband’s support. This had happened in my own family. My father had four unmarried sisters. One volunteered to be housekeeper while the other three obtained work at the envelope factory. This way, they each reached the position of head of a department at the end of their working lives and maintained a reasonably good standard of living.

The factory faced onto a busy Aberdeen street. How I envied all those people outside in comparative freedom while I was chained to these dreadful machines. If it weren’t for weekends, I would most certainly have gone under long ago. Fortunately, I had discovered the Cairngorms and the North West Highlands before I left school and it was immediately apparent that this was where I belonged. This was mainly thanks to a far sighted technical teacher at Frederick Street School. Jim Moir was a very keen hill man who thought it good for us town kids to get a taste of the real outdoors and took a group of us on a climb of Clachnaben on Lower Deeside near Banchory and also Bennachie to the north of Aberdeen. I was immediately hooked. Though I had been born and bred in the town, it was only in the hills that I felt truly alive. Through a long and dreary apprenticeship, every weekend was spent in the blissful freedom of the hills. It was my only escape but however I racked my brain, there seemed no way I could earn a living in the mountains.

I was born in 1935 in a flat on the top floor of a working-class tenement in Seaforth Road in Aberdeen. This was in the heart of the area where Aberdeen’s granite industry was located, and that was still a big employer at that time, though it has gone the way of most of Aberdeen’s industry – paper mills, trawling and others, into oblivion. I had two elder brothers, George, six years my senior and Albert eight years older. My early life was dominated by the Second World War. An early memory is waking up under my mother’s arm (her other arm was holding the family documents in a cardboard box) and being bumped down the common stairs in a great rush to the air raid shelter as the siren sounded. The shelter took up the whole back garden and was built to house the six families of the tenement. There was no sense of deprivation in those wartime days, for you just accept the world you are born into. Our tenement was on the whole a very happy place, the centre one in a block of five solid granite buildings. Each tenement was divided into two and three room flats on either side of a central stairway. On each landing was a lavatory which was shared by two tenants. The flats had no bathrooms but had a scullery where all the cooking and washing took place.

With a total of 30 families within the whole block, there was never a shortage of childhood friends. The summers were spent outdoors. We were well warned of the limits of our freedom, for there were lots of dangerous areas where the military were present, but this left a wide area, chief of which was the Broad Hill at the end of our street. This was at least 100ft high and a great adventure area for us – and to our eyes the perfect playground for our imagination. It had clear views in every direction. To the east lay the beach and North Sea and we could watch all the shipping movements entering and leaving the harbour to the south. To the west lay the familiar layout of Seaforth Road and its tenements, the whole area being dominated by a giant gasometer below which was Pittodrie Park, Aberdeen football team’s home ground. To the north lay the River Don beyond which was an unknown land with a skyline of small areas of woodland with farmland beneath.

There were two events during this time which are engraved in my memory. The first being the visit of a policeman to our house and my mother in a very emotional state. Fearing an enemy landing on Aberdeen beach possibly launched from Norway, the whole of the beach and links were filled by bunkers, tank traps, barbed wire and crucially a large mined area. My brother George and pals were playing golf in the tiny area left to them when one hit a ball accidentally into a mined area which of course was wired off. The young lad whose ball it was crawled under the wire to retrieve it and stood on a mine which killed two or three pals, the full blast catching George on the face and blinding him. A brilliant eye surgeon named Souter spent years extracting steel and sand from his eyes and saved his sight. Though his eyes are still pitted he has good sight even yet.

The second memory is of the air raid on Aberdeen on 21 April 1943. I have no memory of the raid itself. I assume we were all in the shelter and I was told nothing of what happened close to our area in Powis and Causewayend (locally known as Casseyend), but I now know that 98 civilians and 27 soldiers were killed overnight. The news of what had happened had travelled quickly throughout the community next morning. My mother must have been very worried about a close friend who lived very near Casseyend and so next morning, since there was no one to look after me, she had to drag me along to discover if her friend was involved in the casualties. The friend was OK but I saw some of the damage that had been done chiefly to Causewayend church, the side of which had been ripped open, thus exposing the interior like a child’s doll house. (The photograph is still reproduced in wartime Aberdeen books. I must have been there around the same time as the photographer.) It made a very deep impression. (Perhaps I should add that when there were raids, my father, who was in the auxiliary fire service had to go down to Pirie Appleton and fire watch till the raid was over, so my mother had the responsibility of the family during this time).

On to better times. Once the war was over we had more freedom to spend any free time on the beach and the Broad Hill and we had very happy times there in winter, sledging when there was snow and in summer climbing the steeper east side as fast as we were able. We would watch the salmon cobbles go round the nets just off the beach and the prevailing sound of spring was that of the oystercatchers piping and wheeling over our heads. We spent far more time out of doors than children do over half a century later. You have to remember that TV only came to Aberdeen in 1956, that very few people could afford to own one, and that there was only one part-time channel! Staying in with your parents listening to the radio was boring, so you were out the door at every opportunity.

The streets were virtually traffic free in the 1950s and the street was our playground. And most of our games were group games, given that there were so many bairns about after the war. ‘Kick the cannie’ was one game; a can was kicked into the middle of the street and someone (who became IT) had to retrieve it and go search for the others who had hidden meanwhile, capturing them, whilst leaving the can in place. Anyone sneaking out and ‘kicking the cannie’ freed all the captives, and the game started again. This one could go on for hours, and did. Another game was called EIO – and it required a tennis ball. This was thrown against the gable end of the tenement block, the thrower nominating the person who was EIO (or IT). The others scattered but had to freeze when the nominated person caught the ball. He then threw it, and if hitting someone, that person in turn threw the ball against the wall, nominating another catcher, who in turn became IT, and so the game went on… and on… and on. But we were not the only ones playing games…

Strange things were happening on the Broad Hill around this time. Large numbers of men would appear from nowhere and they would gather in large groups. What their purpose was, we couldn’t quite understand, for we were always told to clear off if we came anywhere near them – and even our parents told us not to approach them. It was all very mysterious. Then occasionally, the police would appear and everyone would disappear very quickly. It was only some time later that we realised that what we were witnessing was the operation of a very large gambling school. It took some time for the police to sort it out and we had our hill back again.

From our top flat on a Saturday we could hear the great roar from Pittodrie as the home side, Aberdeen FC, scored a goal. Aberdeen FC – ‘The Dons’ – were doing well at that time, winning their first Scottish Cup in 1947 and then the League in 1955. For me it was always more fun to actually play the game than watch it so I had no inclination to go into the stadium, but the streets around the area were usually filled by fans going to or leaving a match. There was one slightly frightening occasion when a pal and I were at the Castlegate just after the end of an important game. We were waiting for a tram to take us to somewhere, I cannot now recall where. As we waited, the area suddenly filled with fans leaving the game and when a tramcar came along, we were lifted bodily off our feet and carried forward as the crowd surged. Luckily for us, a few men surrounding us saw our predicament and pushed everyone away but it was a very frightening moment when you realised you had no control.

I moved up to Frederick Street Secondary School in 1946. It was a fairly relaxed time. The school playfields, when we were allowed to use them, lay on the links between the Corporation Gasworks and the ICI chemical works, so goodness knows what we were breathing in at the time. We had been taught mainly by elderly women teachers in primary, the male schoolteachers being off to war. Now they returned and in the main were more interested in telling their wartime tales than knocking any sense into us. There were one or two exceptions. One such was Jim Moir, already mentioned. We didn’t realise it at the time but he was much more of an outdoor man. We didn’t know anything existed outside Aberdeen but he helped to put this right by taking a group of us to Clachnaben on Lower Deeside. It opened my eyes to a wider world and its possibilities. He – I think – deliberately took us the long way over the top of Mount Shade, down the far side then up the other, probably in an attempt to slow us down a little, but I still remember the exhilaration of running full tilt all the way down from Clachnaben.

A second expedition took us out to Bennachie. It must have been spring for there were showers drifting across the landscape. My chief memory on the summit was watching the showers leave the cloud and drift across the Aberdeenshire farmland, something I had never experienced before. In Seaforth Road it was either raining or it wasn’t. I decided then, this is where I wanted to be. I was to meet Jim Moir very briefly many years later but that lay far in the future. Ian Mitchell, also an Aberdonian, and aware of where I had spent my early years, drew my attention many years later to Amande’s Bed, a novel by John Aberdein. He had been brought up in the same area as I, albeit a decade later, and it described his early life as the son of a committed Communist Party activist. It was an excellent read with all the real characters I’d known as a child thinly disguised and brought to life again, teachers, neighbours – and even the local shopkeepers! It had the effect of reenforcing all the memories of a very happy childhood.

I left school at 15 and after a year of training at a pre-apprenticeship school, started my apprenticeship with Rossleigh Ltd, agents for Jaguar and Rover. The idea of any further education was never mentioned, but many years later I learned from my mother that my eldest brother had passed the examinations for Gray’s School of Art in the city, and might have been eligible for a bursary to attend. However, this required my father going through a ‘means test’ to see if my brother Albert was eligible for financial help. Possibly with memories in his mind of the Means Test of the 1930s and the humiliation that had involved for those subject to it, my father refused to comply. So began my working life for the next decade or more.

Here is a strange thing. In the earliest days after leaving school and making new friends in the tiny climbing world of the time, it was natural for us to continue our friendship during the normal working week. There was not a great deal to do in Aberdeen if you had very little money and were too young to go into a pub of an evening. The only alternative appeared to be the cinema and there was a wide choice here with much more interesting films than those made today. (Despite not managing to get to Art School, my brother Albert initially became an illustrator working on the advertising posters for the cinema in Aberdeen, mostly then owned by the Donald family who also owned Aberdeen FC.) However, the ‘pictures’, as we called them, were not satisfactory, for we couldn’t discuss the last weekend or the next. Someone came up with a cheap alternative: snooker.

There was a large snooker hall directly above Collies the grocer on Union Street, famous for the wonderful smell of coffee which percolated from its premises. The problem was that snooker was regarded as the Devil’s Work at the time. No good would come of you if you idled your hours away on such a terrible past-time, our elders said. I can’t imagine what our betters thought we got up to there. So the practice was to pretend to be slowly passing by, have a quick look up and down Union Street to see if there was anyone we recognised, and to slip in quickly and spend the evening wickedly playing snooker and planning the next weekend in the hills. That was becoming my real passion.

CHAPTER ONE

The Post-war Birth of Cairngorm Bothying

I WAS INTRODUCED to mountaineering in the changed days after the Second World War, and one of the greatest changes was the emergence of the tradition of bothying, especially in the Cairngorms. Bothies were old gamekeepers’, shepherds’ or sometimes foresters’ houses, which were gradually being abandoned from about 1940 onwards, providing a new source of accommodation in the great outdoors. And for us of limited means, for whom even youth hostels were an expensive luxury, they had the great advantage of being free.

I think my first experience of a bothy was probably around 1949 at the Spittal of Glenmuick where Jock Robertson would allow walkers and climbers to use a barn for an overnight stay and as a base for climbing on Lochnagar or walking over to the Angus Glens. Jock, the keeper for Glenmuick, was a very amiable person who had a good relationship with the climbing fraternity and as a very young lad, I well remember how Jock walked on the hill. While we raced on and then stopped for a rest, we would look back and see him with his steady, measured stride, plodding relentlessly up the path without ever stopping. He covered the ground as fast as we did with our quick dashes and rests and we soon realised this was how you best moved over this kind of terrain. It was a case of building stamina and lung power, and we did our best to copy his style and curb our competitive instincts. The barn was great as a first experience but almost immediately we discovered that by walking another mile or so to the edge of Loch Muick, we could have the greater freedom of Lochend bothy, for there we could have the benefit of a fire with an ample supply of wood from the adjacent stand of trees. This gave the advantage of year-round use for climbing and skiing. Lochend was a very basic building, being a simple, rectangular, wood-lined room, measuring around 30ft by 15ft, with a fireplace on one gable and the then standard two half doors as an entrance. It could accommodate a large number of climbers and became a popular base where lifelong friendships were made.

Without doubt, however, the most popular bothy by far was Bob Scott’s bothy at Luibeg which was situated in Glen Derry and well placed for reaching the higher Cairngorms. The bothy was in a wooden outbuilding which stood a little back from Luibeg cottage where Bob, like generations of Derry keepers before him, lived. It was a cosy doss with a good fire; sadly, the building was burned down in the early 1980s and is no more. Bob had the roughest tongue of anyone I knew, which at first meeting could be very intimidating, but it was all just a front he put on as a way of making sure you had no doubt as to whose interests came first. So a conversation with Bob would usually go like this.

He would be in his usual position on a Saturday evening, hands deep in plus four pockets, leaning heavily against the open door of the bothy as we brewed up.

‘Far are ye gyan the morn, lads?’ He would ask innocently.

We would respond by saying something like, ‘We were thinkin o’ Corrie Etchachan.’

Bob: ‘Fit!! Ye’re bloody well nae. I’m shootin’ hinds at the heid o’ Derry on Monday. If I catch ony o’ you buggers up there the morn scatterin’ my beasts, I’ll kick yer backsides a the wye doon tae Braemar! I think ye wid be better gyan on tae Macdui the morn.’

So, Macdui it was then.

If the Sunday happened to be a bad day, he would very often grab me. As an apprentice mechanic, I often had to repair a broken spring on his ancient 1934 Rover saloon but more often help in other ways.

Bob: ‘Ye winnae be gyan on the hill the day.’

Me: ‘Weel—’

Bob: ‘That’s fine, ye can gie me a han’.

In his barn, he had a huge single cylinder diesel engine and I was useful in getting it started. To get it going, you had to pull a lever to decompress the cylinder, then with a crank you had to turn the engine as fast as you possibly could until there was sufficient speed, then throw the decompressor and this monster would slowly come to life. I can still hear the slow thump, thump, thump as it reluctantly got into its stride. Its purpose was to drive a fearsome circular saw which was outside and connected to the engine by a large belt connected to it through a hole in the wall of the barn.

Bob would find gigantic Scots Pine branches in Glen Derry, blown down in some gale and use his horse to drag them down to Luibeg. They were still too big to lift on to the saw bench and Bob would produce a two man saw of which I had very little knowledge. In my efforts to keep up, I would inadvertently push instead of pull and lock the saw in the cut.

‘Dinnae push, jist pull ye daft bugger!’ he would shout as I struggled to keep up with him

Being on the other end of the log as he pushed it into the circular saw was even more worrying. You could hear the whine of the saw slowing and the engine labouring as Bob enthusiastically fed the log in until I was aching to pull it back. But only at the very last moment would he allow the engine and saw a little respite.

Bob was unwittingly the person who helped to shape my future life. I remember clearly one morning just as I was setting out to the hill, we met at the edge of the Derry wood.

‘Hiv ye ever seen a capercailzie nest?’ he asked.

I hadn’t the faintest idea of what a capercailzie was. At that age I was only interested on rock to climb or snow to ski on. So I had to say, ‘No.’

He then led me to the edge of the wood and pointed to the base of a Scots Pine.

‘There can ye see it?’

I could see nothing and Bob, seeing my mystification said, ‘Are ye blin’ man? There jist at the bottom of the trunk.’

I could still see nothing. So in exasperation, Bob, who named a succession of Jack Russell terriers Freuchan, called to the dog and sent it forward a few paces then called it back.

‘There now can ye see it?’

At last I had detected a small movement and once my eye was in, I could see this huge bird sitting motionless until the dog forced a slight movement. I thought it was absolutely marvellous that such a large bird could merge so completely into the background to protect its nest. This was the beginning of an interest in wildlife which eventually enabled me to leave the restrictions of an urban engineering life to one where I was free to build a business based on the outdoors and which kept me in employment until I retired.

Despite the rough exterior Scott presented to the world, he had a tremendous sense of humour and an infectious laugh, with marvellous stories to tell; we all loved him. Stories about Bob, and Bob’s own stories, are legion. Here a couple will have to suffice.

One of Bob Scott’s tales was of a very early incident from his custodianship. It must have been about 1950 or earlier. There were very few people on the hills around Derry at that time and these two lads appeared who were hoping to get on to Braeriach and had a word or two with Bob on the way past. Some hours later one returned in an exhausted state to say his friend had collapsed somewhere between Corrour and Braeriach and that he had to come back for help. There was no mountain rescue in these very early days so Bob had to take the horse and trap down to Inverey, the location of the nearest phone, to contact the doctor in Braemar. He then gathered some of the other keepers and came back to Derry where there was one of those bamboo stretchers and they made their way into the Lairig, found the chap, strapped him into the stretcher and carried the unconscious man down to Derry – not an easy task. By this time the doctor had arrived.

According to Bob’s account, they released the man from the stretcher and instead of the doctor immediately doing some resuscitation, he rifled through his pockets and brought out what to Bob looked like a packet of sweets. He popped one of these into the man’s mouth and within minutes, the man was on his feet again. When Bob told a story like this his voice always rose an octave in mock indignation. ‘If I kent a’ I hid tae dae wis ti’ pit a sweetie in his moo’, the bugger wid hiv bin able to walk aff the hill himsel’, athoot needin carriet.’

It seems the man was a diabetic and had gone into a coma with the exertion of going uphill and the companion was unaware of his medical condition.

Another story involved ourselves. It must have been a holiday weekend and we had ended up camping at the Derry wood, and having more or less run out of food on the Monday. I think all we had left was a tin of stew between four of us. We desperately needed something else to eke it out.

Bob at that time had a tattie patch near where we were camping surrounded by a high deer fence.

We looked longingly at this. There was no sign of Bob, so while the others kept watch, one of us nipped in, pulled out a few tatties from the middle of the row so it wouldn’t be noticed and started boiling them up along with the stew. To our horror we heard Bob whistling as he left the house and crossed the long bridge over the Lui Burn and headed straight for us.

‘Fit like, lads?’ he said cheerfully.

We all tried to look laid back and casual but inside we were all uptight. We knew what was coming if he discovered what we had been up to. He then looked at the tatties and stew bubbling away in the dixies on the primus and said, ‘Tatties and stew the day, is it?’ ‘Aye,’ we said, trying to look unconcerned at the question.

Desperate to find some distraction, someone blurted out, ‘We were in the Dubh Glen jist now and we saw a few deer carcases. Will ye hae tae beerie them?’

Thankfully, that did the trick. Bob’s interest was now taken up by an extra duty he would have to take care of and he asked directions as to where the dead deer were lying and off he went again, already thinking of the next day’s task. Immediately he was out of sight, we all heaved a great sigh of relief for we had just escaped a real tongue lashing.

Some of his tales were greatly humorous, and possibly a little tall. Bob was no respecter of persons – whatever their rank – and one day he entertained us with a tale of one of the ‘toffs’ who had recently visited the estate. As far as I recall, these were roughly his words.

‘This mannie could hardly climb oot o’ his bed in the morning nivver mind ging up a hill. He wis blin as a bat. I hid tae pit the barrel o’ the gun aginst the stag and tell him tae pull the trigger. If I hidnae daen that I wid hae tae chase the puir wounded beastie a’ o’er the Cairngorms till I got a clear shot. I hope tae hell he disnae come back. Min you, I dinna think he’ll last another year himsel’.’

It’s hard to estimate how many climbers from Aberdeen and surroundings there were in the early 1950s. As most of us worked on a Saturday morning, it was usual for us all to arrive in Bon-Accord Square to catch the 3.15pm bus to upper Deeside. There were usually two buses, one to Ballater, useful for Lochnagar and one to Braemar for the higher Cairngorms and the climbers would fill the back-end of each bus so that would amount to something like 50 at the very most. Travelling by bus and using the same bothies, we got to know each other very well and depending on where you hoped to go that particular weekend, you would join up with anyone who had the same climbing destination in mind. So the make-up of various groups would ebb and flow depending upon the interests of the various individuals at the time.

One of our group was George MacLeod, who would later go to the Antarctic, but at this time he had found himself a job with the Atholl estates as a forester. He would spend the week at Blair Atholl and come home every fourth week or so, bringing with him some interesting intelligence. He told us of the Tarf bothy, lying in an off-shoot of Glen Tilt and how it had more or less been abandoned with most of its furnishings left intact. We had to see this! The details of the timing of the walk in are still a little hazy in my mind but it must have been a holiday weekend when we had more time because I am sure we spent the first night at the Bynack stables which lay about 12 miles west of Braemar, near the entrance to Glen Tilt. Bynack was still in a reasonable state at that time. There was at least one good, habitable, wood-lined room though the other parts were beginning to deteriorate quite badly. Now I believe it is pretty ruinous.

Next morning, we set off up the Bynack Burn and keeping An Sgarsoch on our right, passed over the hill and made our way up the Tarf Water. George hadn’t exaggerated. The bothy was still fully furnished. There was a beautiful large, round mahogany table with a few chairs and a large dresser containing a full set of crockery. Jim Robertson had carried a large potted head all the way from Aberdeen and he now placed this on an elaborate ashet and we each spooned off a piece on to a matching plate. Bothying at its best. But I have to say, it was a creepy place at night.

Another foray into this area was during a September holiday weekend. We wanted to cover a large triangle by walking the old drovers’ route over the Minigaig Pass. This entailed walking through the Tilt, crossing the Minigaig into Feshie, then returning through the Geldie. Something of a marathon in three days fully laden but with George’s intelligence it was just possible. He knew of a bothy at the southern end of the Tilt which we could use.

For some reason I cannot now remember, the first day’s walk involved us travelling the southern end of the Tilt in complete darkness. We relied on George’s knowledge to find Gilbert’s bothy. To this day I have no clear idea of where it was, as I can no longer find it, though I assume it was near Gilbert’s bridge, but I can still remember every bump in its cobbled floor. The next day we set off very early, on across the top of the Bruar Falls and connecting with the Minigaig, thereafter over the high pass and down into the bothy of Ruigh-aiteachain in the Feshie. We knew this bothy very well for we used it at least once every year. It was our habit to spend our annual week’s holiday, climbing somewhere in Skye or the North West and we would start the week by walking through the Feshie and finish the week by returning through the Lairig Ghru or vice versa.

Ruigh-aiteachain was in a very bad state then. The army had been using it as a training ground during the war and anything of any value had long since disappeared. At that time, it consisted of one barely habitable room with a door which was jammed shut. The only entrance was through what had been the window and at night a sheet of corrugated iron was placed over the gap to stop the rain and wind coming in. (My wife and I made a nostalgic visit to Ruigh-aiteachain a couple of years ago and were amazed at the transformation, after several years of maintenance by the Mountain Bothies association. It’s now quite palatial by comparison, though the familiar bothy smell of wood-smoke, wet socks and cooking brought pleasant memories flooding back.)

On our September walk all those years ago, we completed our triangle by walking back to Braemar via the Geldie. It’s a glen we were not enamoured with. It had a bothy, Ruigh nan Clach but we could find no reason to stay there. The Geldie was one of those places which you had to pass through in order to get to the Feshie or the Tilt and the bothy could be useful as a fall back if something went wrong, but the glen wasn’t particularly attractive. There was, however one encounter there which I now regret. We were headed one dark night for Bynack, probably with the ultimate aim of going into the Tilt. Somewhere between White Bridge and Ruigh nan Clach, we heard the slow clip clop of hooves and out of the gloom emerged this figure, leading a pony with a stag carcase across its back. The man was very surprised to meet five shadowy figures moving towards him and said very curtly, ‘Where the hell are you going?’

We had learned never to be too specific and simply replied, ‘Oh, towards the Tilt.’

At this he lost his temper and said, ‘You’re bloody well not! You will turn round and get back to where you came from!’

There then began a real ding dong of an argument back and forth. He saying we had no right to be there and we saying we had every right. Finally, one of our group said, ‘Where does your jurisdiction end?’

I think he then said, ‘Bynack.’

So we said, ‘That’s OK then, we are passing through into the Tilt and you can’t stop us.’ With that he had to admit defeat and he disappeared into the darkness again.