3,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

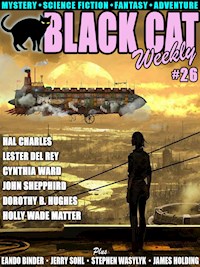

- Herausgeber: Wildside Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

This issue brights quite a selection of mysteries and crime stories—8, in fact. (Though two are doing double-duty as science fiction.) Michael Bracken has selected a story by our acquiring editor Cynthia Ward for this issue—“Roadsong,” which (along with Eando Binder’s tale) is also science fiction. Barb Goffman has picked a winner by John Shepphird this issue. Plus we have classics by Stephen Wasylyk, James Holding, Dorothy B. Hughes, and Nicholas Carter. And what issue would be complete without a solve-it-yourself mystery by Hal Charles?

On the science fiction side, Cynthia Ward has picked “Memorabilia,” a post holocaust story, by Holly Wade Matter, plus we have a classic fantasy by Lester del Rey (from Unknown), and a classic science fiction story by Jerry Sohl (from Infinity). Here’s the complete lineup:

Mysteries / Suspense / Adventure

“Alligators Don’t Ask for Payment,” by Stephen Wasylyk [short story]

“Shima Maru,” by James Holding [short story]

“A Ring of Truth,” by Hal Charles [solve-it-yourself mystery]

“Of Dogs & Deceit,” by John Shepphird [short story]

The Bamboo Blonde, by Dorothy B. Hughes [novel]

Following a Chance Clue, by Nicholas Carter [novel]

“The Sign of the Scarlet Cross,” by Eando Binder [short story]

“Roadsong,” by Cynthia Ward [short story]

Science Fiction & Fantasy

“The Sign of the Scarlet Cross,” by Eando Binder [short story]

“Roadsong,” by Cynthia Ward [short story]

“Memorabilia,” by Holly Wade Matter [short story]

“Death in Transit,” by Jerry Sohl [short story]

“Anything,” by Lester del Rey [short story]

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 830

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

THE CAT’S MEOW

TEAM BLACK CAT

ALLIGATORS DON’T ASK FOR PAYMENT, by Stephen Wasylyk

SHIMA MARU, by James Holding

A RING OF TRUTH, by Hal Charles

OF DOGS & DECEIT, by John Shepphird

THE BAMBOO BLONDE, by Dorothy B. Hughes

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

FOLLOWING A CHANCE CLUE, by Nicholas Carter

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

CHAPTER 15

CHAPTER 16

CHAPTER 17

CHAPTER 18

CHAPTER 19

CHAPTER 20

CHAPTER 21

CHAPTER 22

CHAPTER 23

CHAPTER 24

CHAPTER 25

CHAPTER 26

CHAPTER 27

CHAPTER 28

THE SIGN OF THE SCARLET CROSS, by Eando Binder

ROADSONG, by Cynthia Ward

MEMORABILIA, by Holly Wade Matter

DEATH IN TRANSIT, by Jerry Sohl

ANYTHING, by Lester del Rey

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

Copyright © 2022 by Wildside Press LLC.

Published by Wildside Press, LLC.

wildsidepress.com | bcmystery.com

*

“Alligators Don’t Ask for Payment” is copyright © 1997 by Stephen Wasylyk. Originally published in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine, July/August 1997. Reprinted by permission of the author’s estate.

“Shima Maru” is copyright © 1981 by James Holding. Originally published in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine, January 1981. Reprinted by permission of the author’s estate.

“A Ring of Truth” is copyright © 2022 by Hal Blythe and Charlie Sweet. Reprinted by permission of the authors.

“Of Dogs & Deceit,” by John Shepphird is copyright © 2014 by John Shepphird. Originally published in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine, November 2014. Reprinted by permission of the authors.

The Bamboo Blonde by Dorothy B. Hughes was originally published in 1941.

Following a Chance Clue, by Nicholas Carter, is copyright © 2022 by Wildside Press LLC. Originally published in 1899. The text and punctuation has been modernized for this edition.

“The Sign of the Scarlet Cross,” edited and revised text, is copyright © 2022 by Wildside Press LLC. Original version published in The Phantasy World, April 1937.

“Memorabilia,” is copyright © 2001 by Holly Wade Matter. Originally published in Bending the Landscape: Horror. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Roadsong” is copyright © 2018 by Cynthia Ward. Originally published in Pulp Modern 2.3. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Anything” is copyright © 1939, 1967 by Lester del Rey. Originally published in Unknown, October 1939. Reprinted by permission of the author’s estate.

“Death in Transit,” by Jerry Sohl, originally appeared in Infinity Science Fiction, June 1956.

THE CAT’S MEOW

Welcome to Black Cat Weekly #26.

This issue brights quite a selection of mysteries and crime stories—8, in fact. (Though two are doing double-duty as science fiction.) Michael Bracken has selected a story by our acquiring editor Cynthia Ward for this issue—“Roadsong,” which (along with Eando Binder’s tale) is also science fiction. Barb Goffman has picked a winner by John Shepphird this issue. Plus we have classics by Stephen Wasylyk, James Holding, Dorothy B. Hughes, and Nicholas Carter. And what issue would be complete without a solve-it-yourself mystery by Hal Charles?

On the science fiction side, Cynthia Ward has picked “Memorabilia,” a post holocaust story, by Holly Wade Matter, plus we have a classic fantasy by Lester del Rey (from Unknown), and a classic science fiction story by Jerry Sohl (from Infinity).

Here’s the complete lineup:

Mysteries / Suspense / Adventure

“Alligators Don’t Ask for Payment,” by Stephen Wasylyk [short story]

“Shima Maru,” by James Holding [short story]

“A Ring of Truth,” by Hal Charles [solve-it-yourself mystery]

“Of Dogs & Deceit,” by John Shepphird [short story]

The Bamboo Blonde, by Dorothy B. Hughes [novel]

Following a Chance Clue, by Nicholas Carter [novel]

“The Sign of the Scarlet Cross,” by Eando Binder [short story]

“Roadsong,” by Cynthia Ward [short story]

Science Fiction & Fantasy

“The Sign of the Scarlet Cross,” by Eando Binder [short story]

“Roadsong,” by Cynthia Ward [short story]

“Memorabilia,” by Holly Wade Matter [short story]

“Death in Transit,” by Jerry Sohl [short story]

“Anything,” by Lester del Rey [short story]

Until next time, happy reading!

—John Betancourt

Editor, Black Cat Weekly

TEAM BLACK CAT

EDITOR

John Betancourt

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

Barb Goffman

Michael Bracken

Darrell Schweitzer

Cynthia M. Ward

PRODUCTION

Sam Hogan

Karl Wurf

ALLIGATORS DON’T ASK FOR PAYMENT,by Stephen Wasylyk

Everyone lives through a bad year occasionally. The one I was having could definitely be called the Mother of All Bad Years, earned me an invitation to appear on a TV talk show, and left the audience weeping.

My wife had departed and divorced me, taking with her all the assets I foolishly believed had been mutually owned, including the semi-mansion she had insisted we had to have to hold our heads high.

Not an unusual tragedy, and the material loss really didn’t bother me. If you’re young enough, what you’ve earned once, you can earn again. Being betrayed by someone you trusted implicitly, who lied so magnificently she should have been awarded the Croix de Ananias with Crossed Palms, well, that was rather upsetting.

I still rapped the side of my skull with my knuckles each morning trying to decide if I was the most naive male ever taken in by a full moon and the scent of jasmine or if a warm, caring woman had somehow quaffed a witch’s potion that overnight turned her into a mean, vindictive shrew.

Then my mother had died, her eyes faintly accusing as if no son of hers would have allowed such a thing to happen.

But as they say, bad things come in threes.

The small corporation I worked for acquired a new CEO, who strode into the lobby shouting, “Line up, everybody! It’s downsize time!” He then proceeded to fire every fourth standee like a Nazi Oberleutenant selecting villagers for execution. Naturally, I was eighth in line.

Really hadn’t happened exactly that way, of course, but it certainly felt like it.

It didn’t end there. My severe mental stress created physical symptoms that put me in the hands of the medical profession. I was pounded, scanned, bled, and X-rayed, and as though I were a side of beef being examined to see if I was fit for consumption, a variety of probes were inserted into my body’s natural orifices by gaily chatting inserters undoubtedly hoping for an excuse to create a few new ones. A very humiliating and demeaning experience.

Stealing a man’s money can’t compare to stealing his dignity. My ex-wife’d had a great deal to answer for.

With no medical insurance to speak of, the enormous bills wiped out what little money I had left. Flat-ass broke was too mild a term for my financial condition when I extracted a letter from the mailbox in my one-step-above-homelessness apartment house, giving only a passing thought as to how the mailbox predators had missed it. They considered everything to be addressed to them, possibly because they couldn’t read.

From the return address, a law firm, I assumed it to be just another dunning letter threatening suit if I didn’t pay. One had irritated me so much, I’d picked up a stone, marched into the attorney’s office, placed it on his desk, and told him to squeeze it. When it cried for mercy, he could expect a check.

Then I noticed the postmark. Clayton, Pennsylvania.

My mother had been born on a farm near there.

Sucking the painful paper cut I had given myself by opening the heavy, cream-colored envelope too hastily, I read the stilted legalize that informed Stanford Hardee that his Uncle Ralph had passed away and named him principal heir. Interment was—I glanced at the calendar—at nine tomorrow. As executor, Grover Meisser, Esq., thought I might want to attend, after which we could settle the necessary details.

It was a trip I couldn’t afford to make. For the price of a stamp I could authorize him to dispose of the estate and send me the proceeds—if I was stupid enough to ever again trust an attorney. Or for the rest of my life put up with hearing the angry flapping of angel’s wings and my mother’s voice snapping, “He’s your uncle, for heaven’s sake! We don’t do things that way!” “We” was her code word for the family. Very proud of her family, my mother, although I couldn’t see we had ever accomplished much but stay out of jail. So far.

Attorney Meisser hadn’t anticipated an unexplained post office delay before the letter arrived, but I could still make it by catching an evening flight from Florida to Philadelphia, renting a car, and driving three hours through the night.

I reluctantly fanned out my credit cards, looking for one that might not yet have hit the seize-and-destroy list.

* * * *

Dozing on the plane, I remembered Uncle Ralph only vaguely, being seven the last time I’d seen him. A tall, raw-boned, black-haired man, he’d inherited my grandparents’ farm. Certainly my mother didn’t want it. She’d never considered herself a farm girl, leaving at eighteen, meeting my father, and settling in Harrisburg. She was the opposite of Ralph; small, delicate, honey blonde hair. When he wanted to needle her, my father would say she was the obvious result of a mad, clandestine, passionate romance behind the barn between her mother and a traveling salesman—to be told, naturally, “We don’t do things that way.”

We’d visited Uncle Ralph occasionally until my father was transferred to Florida. When my father died, Uncle Ralph hadn’t attended the funeral. For some reason my mother wasn’t angry. She continued to correspond with him regularly.

She’d talked about him through the years; of the fun they’d had growing up on the farm. I’d expressed little interest when she told me he’d never married because a woman had played him for a fool and left him bitter, thinking that there was no way that would ever happen to me. I must have been sixteen when she told me he never left the farm. I took no note of that at all, having more important things on my mind like the mysterious, marvelously smooth white thighs of Heidi Johnson.

Having already classified him as weird, I didn’t consider it odd when he didn’t attend her funeral or when I didn’t hear from him afterward. Now I was his principal heir? Some relatives can’t be explained.

Well, whatever the reason for his self-imposed confinement, he sure as hell had been in no position to object the day they’d carried him off.

* * * *

Only a handful of people were at the interment: a pious-faced, middle-aged minister who read from the Bible without enthusiasm and left immediately without spreading the usual hollow condolences around, as though annoyed that his day had been interrupted, and Tom Wellens and his wife, the neighbors who had done whatever shopping had been necessary for Ralph all those years—what my mother had told me seemed to be true, he never left the farm—and had been rewarded with the farm stock and machinery.

In the inevitable dark suit he wore only at weddings, funerals, and on Sunday, his wife in what might have been severe black bombazine and a wide-brimmed black straw hat decorated with fruit, the Wellenses reminded me of Jack Spratt and his wife, although Mrs. Spratt could never have been so warm and friendly as Mrs. Wellens, the only one of us who wept. Someone like her who weeps sincere tears at the passing of a member of the human race, instead of the hypocritical, socially expected ones, is a member of a rare, slowly vanishing tribe.

And Grover Meisser, the attorney. There are stout men, fat men, stocky men, heavy men. Meisser was in a category of his own, appearing to be a pink, smooth-skinned, ageless inflated doll with perfect teeth and black hair. I suspected both were imported from Korea.

He nodded at me. “Shall we go?”

Since I didn’t intend to stand and weep like Mrs. Wellens, I nodded in return and followed him to his car.

I’d checked into the motel at two in the morning, tried to sleep, couldn’t, had breakfast at seven, and called him.

He’d picked me up, and we’d followed the hearse to the cemetery, nothing unexpected in our completely civilized conversation. Ralph had died in bed in his sleep, he said. Tom Wellens had noticed a lack of activity and had found him. Personally, I noticed the car was recognized, while heads bobbed and hands lifted in recognition, not in greeting but with deference. Meisser was clearly a power in this town.

He got down to business the moment we left the cemetery. “You intend to sell, of course.”

I certainly did, but the assured way he said it made me hedge.

“That’s one option, I suppose.”

The hand on the wheel twitched slightly.

“Oh? You have something else in mind?”

“Depends. What’s the farm worth?”

“I think you can easily get two hundred thousand, perhaps a little more if you wanted to be hardnosed. Several developers are interested.”

I put that down as a probe to see how smart I was. The farm had to be worth more. “Exactly what do I own?”

“The land, the house, its contents, and the other structures.”

“I could lease it out, surely.”

“Hmmm. Risky investment, farming.”

He fumbled a key out of his shirt pocket and handed it to me. “I suggest you check out of the motel and live out there until things are settled. You’ll have to dispose of the contents, but I’m sure there are items of family interest you’ll want to keep. All you need do is stop by my office and sign a few papers. You’ll be liable for the inheritance taxes, but there’s no rush about paying.”

The smug undercurrent in his voice said he knew I’d damned well have to sell part of the property to pay those.

“The title is clear? No outstanding debts or liens?”

“None at all.”

Somehow I didn’t think there were. “He never left the farm. My mother never told me why. Do you know?”

“Oh, it’s no secret. Many years ago he gave a lift to a young girl who lived in town. She accused him of molesting her. He denied it vehemently, but you know how people are inclined to think the worst of anyone. He was arrested, but it never went to trial because the girl finally admitted she’d made up the story to justify getting home late. Ralph was a proud man. As far as he was concerned, his word was his bond, and if he said he was innocent, he expected the people who knew him to believe it. The only ones who did were the Wellenses. So he marched into church one Sunday and told the assembled worshippers that the next time he’d speak to any of them would be in Hell because he certainly didn’t intend to do so in this life. He said he’d never again leave the farm, and if any of them showed up, he’d shoot them and that included the sorry excuse for a minister, whose homily one morning had been how we should all control our basic lustful instincts. You may have noticed a bit of coldness today on the part of the good reverend. Some men of the cloth are no more inclined to forgive than the rest of us.”

At the motel I stepped from the car, leaned down, and said, “Name the time.”

“How about ten tomorrow morning?”

Deep in my head, bells rang, lights flashed, and the word “tilt” appeared. What he should have said was—there’s no rush at all.

* * * *

Some things impress themselves on a seven-year-old mind. The route to the farm was one.

The countryside that flowed by was studded now with clusters of new homes—peaked, gabled, sided with vinyl, glassed, decked—where once, if a crop could grow there and be sold at a profit, it was cultivated. I imagined that from high above those varicolored houses would appear like a strange fungus creeping out from the town and devouring the green valleys.

The farmhouse, barn, machinery shed, and poultry house were painted white and gleaming in the sun at the foot of a gravel access road curling down from the highway that ran by halfway up the hill. Nothing had changed there.

I toured the silent, deserted outbuildings. Everything as neat as a pin and in first-class shape. Family trait.

No rocker or swing on the porch, so I settled at the head of the steps remembering sitting there as a boy, looking down the valley and wondering why everything close was so green while the far hills were a hazy blue.

Aside from what I recognized as half-grown corn, I had no idea what other crops Ralph had been raising in the green and golden fields stretching away from the house. After I sold, the bulldozers would destroy them all, to the chagrin of whatever ghosts of my maternal ancestors might be watching. They considered wasting food a crime.

They’d crossed the mountains with an axe over one shoulder and a Kentucky rifle over the other, cleared the land, fought for it, bled for it, died on it and for it. Two had shed more than their share at Gettysburg, which wasn’t that far away, under a July sun that was still as hard as brass and lay on the shoulders like a weight. Now it had come down to me, the last of the line, and I didn’t want it.

A pickup came down the access road and pulled up behind my rental. Tom Wellens had changed into jeans, a white T-shirt, and a gimme baseball cap. He appeared scrawny, but those corded arms would have the tensile strength of steel wire. He joined me on the steps.

“Would have bet you wouldn’t show, but Ralph said you would. He’ll be here to bury me, he said, because my sister would have raised him right.”

“Don’t know how a man who didn’t come to her funeral could be so sure.”

“Couldn’t come. Laid up. Slipped off the harvester last fall and hurt his hip. Never did come around properly. Did the best he could, but—” he waved at the fields “—none of that would be there without my help. ’Course, we already had a pretty good working arrangement. One man can’t do it all, and help is hard to find.”

“About that hip. He could have let me know.”

“Told him that. Most hard-headed man I ever knew. Wouldn’t listen. Said you’d have enough brains to know that if he could have come, he would.”

“How could he possibly know that?”

“Your mother’s letters. Proud of you, Ralph was, all those honors you took in college and how well you did afterward. Said it was about time the family produced someone with brains.” He chuckled. “Thought it was because of that nonsense that he never left the farm, did you?”

“Nonsense?”

He took off his cap and ran a finger along the sweatband. “Nonsense. Kept it up just to remind those good churchgoers not to judge lest they be judged. They became so used to seeing my wife doing his shopping for him it never occurred to them to think otherwise. ’Course he left the farm, but not so they’d notice. Wasn’t crazy, you know. Didn’t live here like a monk. Good man, Ralph. Too stubborn and high-principled, that’s all.”

I let my imagination tell me what “didn’t live here like a monk” meant.

“These revelations are overwhelming,” I said dryly. “Have any more?”

“Want you to sell, do they?”

“Meisser seems sure I will.”

He replaced the cap and leaned forward, squinting down the valley. “Knew Ralph never would, so they had to do something, didn’t they?”

I stared at him. “What in the hell are you getting at, Mr. Wellens?”

“Told you I found him in his bed, didn’t they? Just another worn-down old farmer whose heart gave out. Let me tell you something. You’ll find one of those recliners inside. Big soft one. Cost him six hundred dollars. Said it was worth every penny because that was the only way he could sleep without pain after he hurt his hip. He never used the bed. But only I knew that. A bit suspicious, don’t you think?”

When someone hints of murder, you either blurt out, “That’s crazy,” or you’re stunned speechless. I was stunned speechless.

“The way I figure it,” he said, “they gave him something to make it look like a heart attack, then put him in that bed so everyone would think he died peacefully. No problem getting away with it if no one suspects.”

I found my voice. A croak, but intelligible. “That makes no sense. They could have left him on the floor. Or in the recliner. No one would have given it a second thought.”

“Sometimes people are too smart for their own good. Man is supposed to die in bed, you put him in it. How could they know he never used it?”

Unchecked assumptions have blown many otherwise foolproof schemes sky high. I felt a chill.

“Did you mention this to anyone? The doctor? The county sheriff?”

“Think they’d have listened?”

Hell no, I thought. They’d have put him down as a crazy old coot.

“So why tell me? Nothing I can do now, is there?”

“You’re his nephew,” he said, as if that answered all questions. “He was very proud of you, the things your mother told him. He’d have left everything to you, but he said you’d know damned-all about farming so it was best that I took the stock land the machinery, but you’d know what to do about the land. I dunno. Must have suspected something would happen. Day before he died, he told me you were to look in your secret place when you showed up.”

“My secret place?”

He shrugged. “Somewhere you used to hide things when you came to visit as a kid.”

Secret place? After thirty years, I was supposed to remember a secret place where I’d hidden things as an imaginative kid?

I rose and dusted off the seat of my slacks. To hell with it. Wellens’ brains had probably been addled from being out in the sun too much. Hadn’t done Uncle Ralph’s much good, either. Not that I was in a position to criticize. Mine hadn’t been working like a computer chip lately, which made the three of us no different from the rest of the country. Everyone is a little nuts.

“Mr. Wellens, I’m going to keep my mouth shut, get as much as I can for this place, and take off for somewhere far away.”

He walked down the steps, turned, and gave me a knowing grin. “Yeah, sure you are.”

I unlocked the door and stepped thirty years into the past. Living alone, Uncle Ralph had no reason to change a thing. The furnishings, from the sofa to the curtains and the lamps in the living room, were exactly as I remembered. So were the oak table, chairs, sideboard, and china closet in the dining room, all waiting to be snapped up by an eager used-furniture dealer. He must have had Mrs. Wellens in to clean once in a while. Not a spot of dust anywhere. Another family trait.

I had no doubt that the bedrooms upstairs harbored a few antiques. I should do well on the house contents alone.

He’d redone the kitchen, though. Everything from the sink to the microwave to the tiled floor was new.

Seemed much smaller than I remembered. Then I realized why.

He’d converted most of the big, old fashioned, farmhouse kitchen, along with the walk-in pantry and house-wide back porch into a two-room apartment suitable for a bachelor. Bedroom and bath in one; den in the other.

I couldn’t help grinning. Why climb stairs if you don’t have to? Now I knew where my pragmatism came from.

A desk and pair of filing cabinets in one corner of the den served as an office. Farming, after all, was a business that required record-keeping, like any other. The recliner Wellens had mentioned stood opposite, facing a nineteen-inch television set on a stand, a VCR below it. No moss on Uncle Ralph. I couldn’t help but feel that if he’d lived a bit longer he’d have bought a computer.

I lowered myself into the recliner and leaned back, sinking into its fabric-covered softness. Easy to understand why he preferred it to his bed. The small table alongside held a reading lamp and a compact AM-FM clock radio. Used when he found nothing of interest on TV, I supposed, or to listen to farm and weather reports.

Against the wall just beyond the table was a shallow bookcase holding small magazines. Four rows of them. I straightened, stretched, and pulled out the first one.

Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine, April 1968.

He must have continually renewed the subscription and saved every copy. Obviously he liked mysteries, yet the shelves held no novels, not even paperbacks. Now that was a mystery in itself. There were, after all, some very good ones out there.

I replaced the book, sank back into the recliner, closed my eyes, and wondered why a hardworking farmer would confine his reading to short stories. Half dozing, I came up with what might be the answer—if I assumed he and I were very much alike, which wasn’t a great assumption at all.

In the evening he could sit here and finish a short story with no difficulty even as his eyes grew heavy; all there, characters, plot, conclusion taken in one bite. With some novels he’d be up against what I’d found. Names would appear, unfamiliar until I realized the character had been introduced thirty pages and three days earlier. References to previous occurrences would make me wonder when did that happen? And sometimes my eyes would drift shut before I reached the end of a chapter or marked the page, and I’d start the next night with where the hell was I?

Half smiling, I thought that Uncle Ralph and I would have gotten along real well. Genes are genes. Our minds traveled the same roads.

And then I straightened the recliner with a crash, walked into the dining room, and crawled beneath the table.

It was big and square with a massive center pedestal, designed to take extra leaves so it could be expanded to seat eight. The leaves were stored above . the pedestal, leaving a space of about two inches where a boy could hide all sorts of good things from the eyes of grown-ups.

My secret place.

I thrust my hand into it, found smooth plastic, and pulled out a miniature tape recorder, easily slipped into a shirt pocket.

Kneeling there, I slid the small switch to Play.

The sound of a door closing, and then, “Been thinking the offer over, Ralph?”

“No thought necessary.”

“Now, Ralph, I told you we have a schedule to meet. A lot of big people, important people, are involved here and they’re getting impatient. Not like you’re being cheated or anything. I’ve been your lawyer for a long time, and I wouldn’t let them do that. You’re getting a fair price. You can go live anywhere, take it easy.”

“Something you don’t know. This hip of mine, now. Poking around in there, they found a cancer they can’t do anything about. One of the wild, fast-growing kind. I’ll be gone in six months, so there’s no reason for me to take all that money, is there? If you don’t mind, I’ll end my days here. Now, if that inconveniences your powerful friends, well, that’s the way it’s got to be. I’m not selling. Not what I want.”

“I’m sorry to hear about the cancer. Really I am. All the more reason for you to take the money. Buy you an awful lot of good care you’ll be needing.”

“Prefer to die where I was born.”

A sigh and menace in the voice. “That could happen sooner than you think.”

A chuckle. “Then you’d have to deal with my nephew. He could be more hardnosed than me.”

“C’mon, Ralph. We looked him up. Wife took off and left him broke, and he lost his job. He’ll grab the money and run.”

Absolutely correct.

“Best thing you can do for him is take the money. You’ll leave him more than he’ll get from us. He’s a loser.”

Insult me if you like, but pay me first.

“Good reason for you to back off and let me die in peace, isn’t it? Tell you what. I’ll sign if they promise to work around me.”

Scrape of a chair being pushed back. “Can’t be done. Commitments have been made and contracts signed. I’ll bring the papers tomorrow night. And a couple of friends. I hope you change your mind by then. Understand, I don’t have any choice. I’m just a big frog in a little pond and do what I’m told.”

“No point to trying to scare me.”

“Not trying to, Ralph. I’m saying they won’t wait to deal with your nephew six months down the road. They’ll say if that’s the way it has to be, do it now.”

“Then I wish them luck, Meisser. I always said that kid had a harder head than mine.”

The sound of a door closing. My thumb was on the off switch when my name stopped me. Ralph’s voice.

“Sanford, the only way you’ll be listening to this is if I’ve joined your mother in some heavenly choir sooner than I wanted to. She ever tell you we had the best voices in the valley? I really don’t know why they want the farm so bad, but then I haven’t studied on it, having more important things on my mind. They offered a million dollars, but hell, money means nothing to a dying man. Time does. Don’t understand why they refuse to give me my six months. One reason I wanted them was to get together with you. But if Meisser robs me of them tomorrow, you do what you think best. If you just want to take the money and go, that’s all right. I haven’t been much of an uncle, so you really don’t owe me a thing. I just hate to see them get away with something. Sorry we never got together, but the years, well, they really slip away, don’t they? My fault, but I want you to know you were never out of my thoughts.”

The recorder hummed.

I rose, pulled out a chair, placed the recorder on the table and sat staring at it, elbows propped, head in my hands, digesting what I’d heard.

No one could argue with what was on the tape. Meisser’s words might not be sufficient in a court of law perhaps, but they were clear enough. He and his friends were on a schedule that couldn’t wait six months for Ralph to die, so they’d hurried him along. Since he was going to die anyway, he hadn’t put up too much of a struggle.

I couldn’t see that a six month delay would make any difference to another housing development. Something bigger had to be involved, particularly in view of the million dollars. Like a mall or an industrial park.

I’d always considered myself easy to get along with. I’d been taught that I was never right a hundred percent of the time but neither was anyone else. Try hard enough and you could always find a middle ground. Schedule or no schedule, something could have been worked out so that Ralph could have died the way he’d wanted to. All it would have taken was a little understanding and compassion, which Meisser and his friends seemed to lack.

No fool, Ralph. Anything he could have written or said to me would have made him sound like a paranoid old man. Reading all those mystery stories, he’d have come across every plot, ploy, and scheme to turn the tables on the villain that any clever author had ever thought of, so he’d adapted one to let me know what went on. He’d made the recording so that I could hear for myself, and hidden it where only I would find it when I showed up to bury him. But I had no real evidence and no way to get any. Even if I could use that recording somehow to have the body exhumed, I could still prove nothing.

I’d also been taught that you never turn your back on a friend, which was what Meisser obviously had done, probably for money. He should have known better. A man who had marched into church and told off the entire congregation and the minister because they’d turned their backs on him would somehow make sure he had the last word.

Ralph was right when he’d said I didn’t owe him a thing. He’d simply thrown the ball to me. My choice to run with it or toss it over my shoulder and walk off the field with a million in my pocket. No question I could get them up to the figure they’d offered him.

Head in my hands, I sat there in that silent farmhouse, alone but for generations of ghosts pressing in on me and waiting to pass judgment on the last of the line.

Nothing I wanted more than to throw my head back and yell,“Hell no! I won’t do it! I’m taking the money and getting out!”

But I couldn’t, and I knew damned well I couldn’t.

Oh, I’d take the money, all right. We were proud, not stupid. But it wouldn’t end there.

The product of a matriarchal lineage where strong women had always set the standards and made the rules, sly old Ralph had known I wouldn’t ignore those ghosts. My mother would have raised me right, he’d told Wellens.

I’d grown up hearing her say, “We don’t permit anyone to tromp on us, dear. We always balance the books.”

She’d have understood but not approved the drastic way I’d balanced mine, but since I was the aggrieved party, it was my choice. Being unemployed, I’d had plenty of time to work it out so that the police questioned me only once after my ex-wife disappeared. I’d had to improvise, of course, since I had no money, but fortunately alligators don’t ask for payment.

Nor would my mother approve of how I’d eventually balance the books for tromped-upon Uncle Ralph. A million dollars would give me plenty of time to work that one out, too.

I might get Meisser to visit me in Florida next winter. No reason for him to refuse a free vacation in the Sunshine State. He had no idea I knew what he’d done to Ralph.

My ex-wife had been on the thin side—a diet dish, you might say. Meisser now…the alligators would consider him more like a really good piece of prime rib.

No point in spending money if it isn’t necessary.

SHIMA MARU,by James Holding

I am Vetuka.

Sometimes, when the Southern Cross burns in the night sky over Savo, my blood speaks to me faintly of times long gone—before whitefella came to destroy forever the ancient ways of our island world. In those far days my ancestors were clan chiefs, mighty warriors who led daring raids upon Ulawa, Maramasike, Nggela, even far-off Kolombangara, who captured many beautiful wives and lived in pride, feasting, when Tongaroa smiled, upon the flesh of their conquered enemies.

I too, for a brief time in my youth, lived in pride. When the yellow men from Japan invaded our island, I, serving as bush scout, helped the American Marines to dislodge them. In gratitude for my services at Gold Ridge, Henderson Field, Kukum, and the Ilu River, the Americans showed me great honor, awarding me the American Legion of Merit. I still wear this beautiful ribbon on the waistband of my shorts, to remind me of past glory.

But that was long ago. Now my hair has grey wires in it which the lime-juice dye cannot conceal; my teeth rot; my last wife is long dead; my two strong sons have left Guadalcanal forever to serve as menial waiters in a tourist hotel on the distant island of Vita Levu. And I, Vetuka, among the last surviving members of our ancient Shark clan, am only a humble fisherman of Honiara.

I dwell in a small house of wood and tin upon the side of a ridge above Honiara waterfront, where my fishing boat lies. From my house, I look out over the anchorage and Point Cruz to the blue wooded hills of Savo Island twenty miles away across Ironbottom Sound. Although four mighty cruisers of war, one Australian and three American, lie rusting on the floor of Ironbottom Sound, victims of Japanese torpedoes and shellfire in the Great War, no sign remains today to speak of this old violence. The sea between the islands lies calm and beckoning and beautiful under the golden sun of the Equator. It is a pretty scene. I never tire of it.

* * * *

Until a week ago, my life seemed to flow quietly and uneventfully toward its appointed end. Then I found the hidden tins of petrol, the tins of preserved food, the plastic bottles of fresh water in the jungle behind my house, and I realized that my nephew Likuva and his Japanese friend Michiko meant to rob me—and possibly kill me.

Until that moment, I had thought they came to me only because of my fishing boat, to seek my help in locating the sunken ShimaMaru and, in payment for my help, to share her treasure with me.

I stared at the cache of petrol, food, and water cunningly hidden in the tall lalang grass. I was surprised at first by this unexpected discovery, nothing more. Then I felt a fierce anger that squeezed my heart—and deep shame for my nephew Likuva, the only son of my dead sister, who many years ago had married a member of the Turtle clan and gone to live on Simbo.

Likuva and Michiko had arrived in Honiara by the inter-island schooner which plies between Port Moresby in New Guinea and Guadalcanal. When they appeared at my small house on the ridge, just as darkness descended upon the island and the lights of Honiara began to glitter below us like scattered cooking fires in the dusk, I was very glad to see them. A visit, I remember thinking, from my nephew and his friend would add interest to my lonely life.

Likuva could have been my own son: short in stature, regal in bearing, muscular, sleek, and powerful, his black skin shining with health as though he had been oiled. I felt a touch of envy for his youth. He was wearing, like me, only a tattered pair of whitefella shorts to hide his nakedness. The Japanese man he introduced as Michiko was nearer to my age than to Likuva s. He was of medium stature, magnificently muscled, and smelled unpleasantly of sweat and whiskey. He wore a loose-fitting tropical shirt of black-and-red material he seemed reluctant to shed even in the burning heat. And, to my great surprise, he had somewhere learned to speak our Melanesian tongue.

I made them welcome, of course. Their arrival stimulated me. I invited them to stay with me in my house and share my sleeping loft for as long as they wished. They accepted my invitation eagerly and settled down at once, treating my home as if it were indeed their own.

“Uncle,” Likuva said to me as we squatted together before my doorway in companionable ease, “it is good to be here. It is so calm, so quiet, so peaceful. After Port Moresby, it seems like coming home.”

“And I know great joy to see my nephew once more after so long a time,” I said to Likuva. I did not know what to say to Michiko. I have never felt entirely at ease with a Japanese since I helped the Americans against them.

As though he had seen into my head, Michiko said, “Likuva has told me about you, Vetuka. What a great warrior you were to win that ribbon.” He glanced down at the faded Legion of Merit at my waistband.

Uncomfortably I said, “That is past history, Michiko—of no importance now.”

“Also,” Michiko went on, not heeding my words, “he has told me what a skillful fisherman you are, what a fine boat you own. And what a wide knowledge you have of all the seas hereabout.”

“My nephew exaggerates,” I said modestly. Nevertheless, I cast a grateful look at my nephew for boasting of me to his friend.

“I told the truth, Uncle,” said Likuva. “My mother never tired of talking about you and your deeds.”

Michiko gave Likuva a quick look. “You do still own a motorboat, don’t you, Vetuka?”

“Yes, of course. It is how I make my living here. But it is not really a fine boat at all, no matter what Likuva told you. I got it fourth-hand from a dying Chinese merchant.”

Michiko smiled. His teeth had spaces between them. “It is a motorboat? Then it must have cost you something, even fourth-hand from a dying Chinese!”

I shook my head. “Only a few pounds. I borrowed the money from the British Information Officer.”

Michiko was silent for a moment. We needed no torch, although full dark had come; the three-quarter moon floating overhead provided plenty of light. The Japanese said, “How big is your boat, Vetuka?”

“Twenty-six feet,” I said proudly. “With an outboard motor of seventy-five horsepower. It has a small wheelhouse with a windscreen from which I control the motor at the stern and steer the boat. It also has enough deck space for my needs.”

“You see?” said Likuva to Michiko. “Just as I told you.”

“It must be a fine boat,” said Michiko. “It has radar and sonar as well?”

“A depthometer to help my fishing, that’s all.”

“Better than nothing,” Michiko said. Then, idly: “What made you take up fishing, Vetuka?”

“Members of the Shark clan do not ‘take up’ fishing,” I said with dignity. “We are born to it. We have always been expert fishermen. One of my ancestors was such a skillful fisherman he is still remembered in our legends.”

“Ro?” asked Likuva.

“Yes,” I said. “Ro. From your island of Simbo.”

“Tell Michiko about Ro,” said Likuva. “It is very amusing, Michiko. My mother told me the story many times when I was a small child.”

“Michiko cares nothing for our legends,” I said.

“Tell the story,” Michiko said. “Then let’s have a drink to celebrate our arrival at Honiara. Do you have any whiskey here, Vetuka?”

“No whiskey. I have beer though.”

For the second time Michiko said, “Better than nothing.” He sighed.

“My ancestor Ro,” I began, “was the best fisherman on Simbo.”

“Yes,” murmured Likuva nostalgically.

“Shut up, Likuva,” said Michiko rudely, “so we can hear the story and get to the beer.”

I went on. “The people of Simbo thought they were uniquely blessed by Tongaroa. They had more beautiful women, more plentiful crops, braver warriors, better fishing grounds than any of the neighboring islands. In fact, they had the best and the most of everything.”

“Except for one thing!” Likuva broke in, taking the words out of my mouth as he must have done many times when his mother told him the tale.

“Except for one thing, yes,” I said.

“What?” asked Michiko without much interest.

“Moonlight,” I said. “The moon shone on all the other islands as brightly as it did on Simbo. This affronted the people of Simbo. They wished to capture the moon and make it shine on them alone.”

“Here’s where Ro comes in,” said Likuva eagerly. “He went fishing for the moon, didn’t he. Uncle?”

“He did. As the best fisherman of Simbo, he was given the job of hooking the moon. He prepared an extra long line, an extra large shell hook, and used the trunk of a small sapling for a pole. If he hooked the moon, he intended to tie his line to the biggest tree on Simbo, to prevent the moon from floating across the sky above any of the other islands.”

“But Ro couldn’t catch it!” Likuva interrupted again.

I nodded. “He cast his hook many times into the night sky without success. And the foolish people of Simbo, in their anger and resentment at the moon for refusing to be caught by Ro’s hook, gathered handfuls of black sticky mud from a swamp and threw it at the moon to dim its shining.” I paused and pointed at the moon above our heads. “Do you see those dark patches on the moon’s face, Michiko? That is the mud thrown by the people of Simbo.”

Michiko yawned widely. “Will you get the beer now, Vetuka?”

As I went to draw the beer from its cooling place in the rivulet beside my cooking shack, I heard Likuva and Michiko talking together in low tones but could not make out their words. They ceased abruptly when I came back to them with the beer.

Michiko took a long draft from his, then placed it carefully on the packed earth between his feet.

“Now I’ll tell a story,” he said.

By all means,” I said politely, sipping my beer. “Is it a Japanese tale?” He grinned. “Very much so,” he said, “but it took place right here in the Solomon Islands.”

I touched my Legion of Merit ribbon. “During the Great War?”

He nodded. “And you will know most of the story, since you were here and it is a true story.”

“I shall be interested to hear you tell it, nevertheless,” I said.

“My story is a tale of eleven Japanese ships,” Michiko said. “Eleven ships loaded with troops and sent to Guadalcanal in November of 1942 to reinforce the Japanese garrison here, which you and your friends, the Americans, had greatly reduced during four months of heavy fighting.”

I nodded, remembering.

“So. The eleven Japanese troopships, steaming toward Guadalcanal, had almost reached the island when American aircraft happened to sight them and proceeded to bomb them heavily. Seven of the troopships were sunk. The four that remained afloat were run ashore on the beach only a few miles west of here.”

“I know the spot,” I said. “The empty hulks of those ships remained there long after the war was over, until the Chinese who came to live in Honiara broke them up for salvage.”

Michiko glanced at Likuva, squatting on his other side.

Likuva said, “Go on, Michiko—tell him the rest.”

Michiko went on. “Of the seven ships sunk by the bombers, one was the ShimaMaru, on which my brother was the captain’s steward. My brother survived the bombing and the sinking. He was a strong swimmer and made it to shore. Later, when he returned home, he told me the part of the story that even you, Vetuka, do not know—the part that nobody knows save Likuva and me.”

“And your brother,” I said.

Michiko shrugged. “He died soon after he told me. He lived in Hiroshima.”

I said nothing.

Michiko spoke slowly. “My brother told me that the ShimaMaru, less badly damaged by bombs than the other ships which quickly sank, almost made it to Guadalcanal before foundering with all hands. She sank not more than two or three miles offshore in relatively shallow water.”

I said, “Your brother was lucky the sharks did not take him.”

Michiko nodded, his broad face showing no emotion.

“Or else,” said Likuva, with a malicious glance toward me, “he was a member of my uncle’s Shark clan.”

Angered at his levity, I began to rise. Michiko said sharply, “Shut up, Likuva. Sit down, Vetuka. Your nephew means nothing by his irreverence. I have not yet told you the ending of my story.”

I squatted down again.

“Did you understand what I said?” Michiko asked. “I said the ShimaMaru sank in shallow water. At a spot where the depth was no more than sixteen fathoms on the captain’s chart, which my brother had been privileged to see many times when he served the captain his meals on the bridge and in his day cabin.”

I nodded. “There is an underwater ridge several miles offshore, running east and west. I have fished there.” I looked at Michiko. “Is this the end of your story?”

Michiko drew a slow, deep breath. “Vetuka,” he said, “do you think you could find the spot where the ShimaMaru lies?”

“Why?” I asked.

“Because,” said Michiko, “there were fifty thousand gold yen on the ShimaMaru when she went down.”

I spilled beer down my chin.

My nephew punched me playfully on the arm. “What do you think of that, Uncle? Is that not even more interesting than your story of Ro?”

“Yes,” I said cautiously, still bewildered, “if it is true.”

“It is true,” said Michiko, enjoying my astonishment.

I said, “Your brother saw the gold, as well as his captain’s navigation charts?” Apparently his brother had seen many things that were not his business.

“Yes,” said Michiko. “My brother had his wits about him always.”

“Clearly,” I said. I took a minute to ponder. “Why would a troopship be carrying fifty thousand gold yen?”

“After unloading its troops in Guadalcanal,” Michiko said, “the Shima Maim was to carry the gold on to the commander of the Japanese base in Rabaul. It said this in the captain’s secret orders, which my brother—”

I waved a hand to interrupt him. “For what purpose was the money to be used in Rabaul?”

Michiko shrugged his shoulders, making the red-and-black flowers on his tropical shirt wiggle in the moonlight. “To bribe the village chiefs? To pay the Japanese troops? Who knows? It is not important. The important fact is that there are fifty thousand gold yen still in the sunken hulk of the ShimaMaru.” Michiko wiped sweat from his forehead. “If you help us to find the ShimaMaru, Vetuka, a third of the treasure will be yours. I promise it.”

I was silent. I gazed steadily at the moon and wondered why Michiko had allowed thirty-five years to pass before coming to Honiara to seek the treasure. I wondered how he came to know my nephew, Likuva, and had thus learned about me and my boat and my knowledge of Guadalcanal waters. I wondered how he came to speak our island tongue so well.

I asked him these questions. And his answers were given without the hesitations that betoken lies. Until he met Likuva in a waterfront bar in Port Moresby and from him learned about me and my boat, said Michiko, he had had neither the time, the resources, nor the opportunity to seek the treasure of which his brother had told him. After Japan was defeated in the Great War, he left his country, unable to tolerate the presence of her conquerors. He shipped south as a deckhand on a freighter, jumped ship in the Philippines, and worked there on a plantation until, in a quarrel over a woman with a fellow worker, he had killed the man and been forced to spend fifteen endless years in the high-security penal colony of San Ramon in Zamboanga.

Released at the end of his term, he had drifted to Australia and dived for pearl oysters off the north coast for ten years. When the pearl diving palled, he had moved on to New Guinea, finding work as a bartender in a Port Moresby dive. There he had remained for the past eight years; there he had picked up our Melanesian speech from his customers; and there he had heard a drunken customer one night—my nephew, Likuva—speak of an uncle on Guadalcanal. On impulse he had told Likuva his secret. Michiko used his scant savings to book passage for the two of them next day to Honiara where, with my help, they hoped they could recover the golden yen in the ShimaMaru. “Will you help us, Vetuka?” asked Michiko.

I saw the eagerness in Likuva’s moon-shadowed eyes and found, for a moment, nothing to say except that fifty thousand Japanese yen seemed scarcely worth the trouble of recovering. “A hundred pounds or so,” I said, “split three ways means very little, Michiko. I can get rich more quickly by fishing.” I gave Likuva a smile.

He did not return it. He said, “Uncle, the yen in the ShimaMaru are gold! Gold! Don’t you understand?”

“No,” I said.

“Allow me to explain something, Vetuka,” Michiko said. “Each gold yen has three-quarters of a gram of pure gold in it. Pure gold! Do you have any idea what the gold in fifty thousand gold yen is worth today?”

I shook my head.

“Over three hundred thousand pounds!” Michiko’s voice was laced with the shrillness of greed. “Think of it! One hundred thousand pounds for each of us! You could own a copra plantation if you desired. You could buy a beautiful new fishing boat with inboard engines!”

I was stunned. “A hundred thousand pounds.”

“If you help us find the ShimaMaru.”

“I cannot conceive of such vast wealth,” I said. “I charge my customers two shillings and sixpence a pound for bonito—and feel great guilt that I demand so much.”

“You will never need to catch another bonito so long as you live, Uncle,” said Likuva, wheedling. “Will he, Michiko?”

Michiko shaded his eyes against the moonlight and showed his teeth in a conspiratorial smile. “Never.”

Likuva asked anxiously, “Will you help us, Uncle?”

Why not? I thought to myself, and stood up. “Yes,” I said. “We will make a plan tomorrow.”

* * * *

Before sunrise the next morning, we left my sleeping loft, descended the ridge to the wharf, boarded my boat, and proceeded, at quarter speed, to round Point Cruz and head west along the shoreline of Guadalcanal.

I kept inshore after rounding the promontory, close enough to make out landmarks in the half light of dawn. Government House, the Masonic Lodge, the soldierly ranks of coconut palms on the Lever Brothers plantation slid slowly by on our left.

When I sighted Kakaombono Village I said to Michiko, “This is where the four Japanese troopships that escaped the bombers were run ashore. I will make this the starting point of our search, since the ShimaMaru, when she sank, must have been on the same course as they.”

Michiko nodded. He gazed with fascination at the spot on the beach where I pointed.

The sun was rising now. I turned the boat due north toward Savo Island across Ironbottom Sound. The sea was calm, the long smooth swells slightly ruffled by the gentle breeze of dawn. Increasing our speed slightly, I kept my eyes on the depthometer installed at eye level to the left of my windscreen.

Twenty minutes later we reached the underwater ridge I had mentioned to Michiko. Gradually the depth of water under us decreased—from sixty fathoms to forty-two, then to twenty and eighteen. Michiko, who was crouching behind my shoulder in the wheelhouse, was watching the depthometer as intently as I. “Sixteen fathoms, Vetuka. Sixteen,” he murmured.

“Yes,” I said, “the ShimaMaru must have gone down on the very top of the ridge. Luckily for us.”

“What do you mean, Uncle?” asked Likuva.

“It will narrow our search.”

“How?”

“Look at the depth gauge, Likuva. And watch it for a moment.”

Two minutes later, the bottom began to drop away below us. At eighteen fathoms, I said, “Do you see, Likuva? We have but a narrow area to search at sixteen fathoms. Less than a hundred yards wide.”

“But,” said Michiko, “many miles in length?”

“Yes,” I replied. “What did you expect? To find the ShimaMaru as easily as you find a lump of meat in a cooking pot?”

“Of course not.”

“However,” I comforted him, “I believe our chance of success is good.”

“Why?”

“The troopships were approaching Guadalcanal from the northwest, down the slot between the islands, when the bombers discovered them. Under sudden attack, they must have fled by the shortest route for Guadalcanal. If their escape course led between Savo and Cape Esperance, we can judge within a mile or two where they must have crossed this underwater ridge in their hurry to get ashore.”

Michiko looked more cheerful.

I turned west and followed the sixteen-fathom depth along the ridge top until instinct and experience told me my boat had intersected an imaginary line drawn from Kakaombono beach to a point midway between Savo Island and Cape Esperance. There I killed the motor, checked our position visually against my landmarks, and climbed from behind the wheel. I said to Likuva, “Throw the anchor overboard.”

My anchor was a heavy stone tied to the end of a thirty-fathom line. Likuva lifted the stone from the deck and dropped it overboard with a splash. The line attached to it snaked into the depths. When the stone preached bottom, I tied a white plastic water bottle, empty and capped, to the slack line on the sea’s surface to serve as a marker.

I said to Michiko, “Yours is the honor of the first dive. But beware of sharks. They are very numerous in these waters.”

“I have no fear of them,” said Michiko stoutly. “In ten years of pearl diving I learned to know them well. I ignore them and they ignore me.”

“Let us hope so,” I said, smiling, “for they are my relatives, after all. Only remember that if she is down there, the ShimaMaru will bulk large on the bottom and cannot be mistaken. Her sister ships, which I saw on Kakaombono beach, were thirty feet from deck to Plimsoll line. Nevertheless, we will need patience and persistence to find her.”

“Thank you, Vetuka,” said Michiko gravely, although his limbs were shaking with excitement. “I was a professional diver, remember. I know something of the art.” He took several slow, deep breaths, expanding his chest to its utmost with each one, then dived cleanly over the transom of the boat and swam downward with strong strokes until the depth of the water hid him from our sight.

* * * *

By day’s end, Michiko and I, taking turns, had made twenty-two exploratory dives in search of the ShimaMaru. After each fruitless dive we moved the boat a hundred yards west along the underwater ridge, anchored, and dived again.

Likuva did not dive. Instead, he quickly learned to handle the boat with great skill, adjusting our positions delicately as I bade him, lest we fail to explore any section of the bottom where the ShimaMaru might lie. Michiko could stay under the water far longer than I. Yet I say without boasting that in spite of my advancing years, I held my own with him in this strenuous work, since my eyesight was keener than his and my knowledge of currents and tides superior.

For three days our search continued. Routinely we rose at dawn, hastened to the underwater ridge as the sun rose, and spent the day diving, diving, diving, with only brief pauses to rest ourselves, to eat, and to move the boat to new locations. Then, as dusk approached, we marked the spot of our last dive, returned to Honiara, secured the boat, ate a hurried meal of fish or turtle meat, and fell like logs into the drugged sleep of exhaustion.

Toward evening of the third day, we found the ShimaMaru.

Michiko, whose turn it was to dive, stayed below for almost four minutes, longer than on any dive before. Then he shot to the surface beside the boat and, the moment his mouth was clear, shouted something in Japanese. Likuva and I did not understand the words, but there was no mistaking the excitement with which they were uttered nor the expression of triumph on Michiko s normally impassive face. As we pulled him aboard, dripping, he switched to our tongue. “She’s there!” he cried. “The ShimaMaru!” He fought to recover his breath.

I said, “Are you sure, Michiko? It is the ShimaMaru?”

“Yes! Yes! She’s down there, directly below, lying on her side, corroded and weed-covered, but it’s the ShimaMaru beyond any doubt. Part of her name is still legible on the bow.”

Likuva’s joy at the discovery manifested itself in loud, mindless laughter. He pounded Michiko on the back with his fist until Michiko sharply asked him to desist. I offered Michiko, the discoverer, a can of tepid beer from the fishbox.