2,73 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Wildside Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

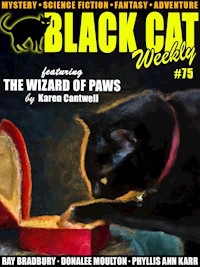

Our 75th issue has a pair of original tales for your reading pleasure, one mystery (“Troubled Water,” by donalee Moulton, thanks to acquiring editor Michael Bracken) and “The Forbidden Scroll,” by Phyllis Ann Karr (a solo adventure by Frostflower from Karr’s Frostflower & Thorn series—we had a solo Thorn adventure last issue.] Barb Goffman has selected a cat-themed mystery by Karen Cantwell, plus we have classic mysteries by Hal Meredeth (Sexton Blake) and Norbert Davis (a hardboiled novel). On the science fiction side, we have a great set of tales by George O. Smith, Ray Bradbury, Noel Loomis, and William Tenn…all favorites of mine.

Here's the lineup:

Mystery & Suspense:

“Troubled Water,” by donalee Moulton [Michael Bracken Presents short story]

“A Death in the Department,” by Hal Charles [Solve-It-Yourself Mystery]

“The Wizard of Paws,” by Karen Cantwell [Barb Goffman Presents short story]

“A Confidential Report,” by Hal Meredith [Sexton Blake short story]

Oh, Murderer Mine, by Norbert Davis [novel]

Science Fiction & Fantasy:

“The Forbidden Scroll,” by Phyllis Ann Karr [Frostflower short story]

“The Cosmic Jackpot,” by George O. Smith [short story]

“The Square Pegs,” by Ray Bradbury [short story]

“Softie,” by Noel Loomis [short story]

“Consulate,” by William Tenn [novelet]

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 438

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

THE CAT’S MEOW

TEAM BLACK CAT

TROUBLED WATER, by donalee Moulton

A DEATH IN THE DEPARTMENT, by Hal Charles

THE WIZARD OF PAWS, by Karen Cantwell

A CONFIDENTIAL REPORT, by Hal Meredith

OH, MURDERER MINE, by Norbert Davis

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

THE FORBIDDEN SCROLL, by Phyllis Ann Karr

THE COSMIC JACKPOT, by George O. Smith

THE SQUARE PEGS, by Ray Bradbury

SOFTIE, by Noel Loomis

CONSULATE, by William Tenn

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

Copyright © 2023 by Wildside Press LLC.

Published by Wildside Press, LLC.

wildsidepress.com | bcmystery.com

*

“Troubled Water” is copyright © 2023 by donalee Moulton and appears here for the first time.

“A Death in the Department” is copyright © 2022 by Hal Blythe and Charlie Sweet. Reprinted by permission of the authors.

“The Wizard of Paws,” by Karen Cantwell is copyright © 2017 by Karen Cantwell. Originally published in The Purr-fect Crime: Happy Homicides #5. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“A Confidential Report,” by Hal Meredith, was first published in Answers,Sept. 12, 1908.

Oh, Murderer Mine, by Norbert Davis, was originally published in 1946.

“The Forbidden Scroll” is copyright © 2023 by Phyllis Ann Karr and appears here for the first time.

“The Cosmic Jackpot,” by George O. Smith, was originally published in Thrilling Wonder Stories, October 1948.

“The Square Pegs,” by Ray Bradbury, was originally published in Thrilling Wonder Stories, October 1948.

“Softie,” byNoel Loomis, was originally published in Thrilling Wonder Stories, October 1948.

“Consulate,” by William Tenn, was originally published in Thrilling Wonder Stories, June 1948.

THE CAT’S MEOW

Welcome to Black Cat Weekly.

Our 75th issue has a pair of original tales for your reading pleasure, one mystery (“Troubled Water,” by donalee Moulton, thanks to acquiring editor Michael Bracken) and “The Forbidden Scroll,” by Phyllis Ann Karr (a solo adventure by Frostflower from Karr’s Frostflower & Thorn series—we had a solo Thorn adventure last issue.] Barb Goffman has selected a cat-themed mystery by Karen Cantwell, plus we have classic mysteries by Hal Meredeth (Sexton Blake) and Norbert Davis (a hardboiled novel).

On the science fiction side, we have a great set of tales by George O. Smith, Ray Bradbury, Noel Loomis, and William Tenn…all favorites of mine.

Here’s this issue’s lineup:

Mysteries / Suspense / Adventure:

“Troubled Water,” by donalee Moulton [Michael Bracken Presents short story]

“A Death in the Department,” by Hal Charles [Solve-It-Yourself Mystery]

“The Wizard of Paws,” by Karen Cantwell [Barb Goffman Presents short story]

“A Confidential Report,” by Hal Meredith [Sexton Blake short story]

Oh, Murderer Mine, by Norbert Davis [novel]

Science Fiction & Fantasy:

“The Forbidden Scroll,” by Phyllis Ann Karr [Frostflower short story]

“The Cosmic Jackpot,” by George O. Smith [short story]

“The Square Pegs,” by Ray Bradbury [short story]

“Softie,” by Noel Loomis [short story]

“Consulate,” by William Tenn [novelet]

Until next time, happy reading!

—John Betancourt

Editor, Black Cat Weekly

TEAM BLACK CAT

EDITOR

John Betancourt

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

Barb Goffman

Michael Bracken

Paul Di Filippo

Darrell Schweitzer

Cynthia M. Ward

PRODUCTION

Sam Hogan

Karl Wurf

TROUBLED WATER,by donalee Moulton

There is a knot in my stomach that tightens every time I press the start button. And nothing happens. The Keurig coffeemaker refuses to cooperate. It simply sits there blinking blue. Now the knot is moving further up my abdomen and across my kidneys and lodging in my lower back.

When I was the police chief in Humboldt, Saskatchewan, I could just duck out the door to the nearest Walmart and have a replacement in mere minutes. But I’m currently a police chief in the Canadian north, a mere 3,200 kilometers from the Arctic Circle, and there is no Walmart. There is no department store of any kind. Amazon delivers in three to five days (it used to be three weeks), but coffee in a climate where temperatures can routinely hit -13 degrees Fahrenheit is not simply nice to have, it is essential.

There is a Facebook marketplace that might be the best option. I turn to ask Ahnah Friesen, the Iqaluit Constabulary’s exceptional executive assistant, what she’d recommend we do in this crisis. Before I can say anything, however, our front door swings open and David Picco, the member of the legislative assembly for Rankin Inlet strides in.

“Got a minute,” he says, heading for my office. It is not a request.

David Picco is the man responsible for getting the local police force established—a first for the territory of Nunavut—and the person responsible for me being here in Iqaluit without a coffeemaker. He’s also a mentor and a friend.

I’m right behind him. Coffeeless. “What’s up?” I ask before the door shuts behind me, something we rarely do here and a harbinger of bad news to come.

“I’d like you to come with me,” David says. “We have a situation. It doesn’t appear to be a police matter, but I’d like your input.”

“Of course,” I say without hesitation. “How can I help?”

“Not sure,” says David. “I’ll tell you what I do know on the way.”

We’re heading down Mivvik and turning on to Queen Elizabeth past the post office. David is clearly rattled. I wait silently. My training as a cop in the south has taught me that. Lack of caffeine makes it easier.

“A young man has died,” David finally says. “It might be the water.”

“Shit,” I say sitting up straighter. The knot is back.

Water is a hot-button issue in Iqaluit. Residents have repeatedly complained about the smell of fuel every time they turned on their taps, and last year the city’s 8,000 residents had to use bottled water for two months when it was confirmed something potentially toxic was in the water. That something was fuel. It turns out a sixty-year-old underground fuel tank was buried next to the water treatment plant. Remediation and cleaning are under way, but many people in town feel efforts are too little, too late.

David brings the Ram 1500 to an abrupt halt in front of a green and grey apartment building on Aiviq Street. The coroner’s Subaru Crosstek and the city’s one ambulance are parked out front. “Second floor,” David says.

“I don’t want to influence what you see,” he adds by way of explanation. “And I don’t want to see that room again unless I have to.”

There is no elevator, not unusual in Iqaluit, and the stairs have seen better days, also not unusual. There is a group of people outside the third apartment on the left. “Doug Brumal,” I say by way of introduction. “Police chief.”

That creates a stir. A clear voice from inside yells out, “What the hell are you doing here?”

That would be Kari Frost, the chief coroner. I make my away around two paramedics, one gurney, and a clutch of what I presume are other tenants. Kari is on her knees in front of a motionless man. A stethoscope dangles from her neck. Kari nods in my direction as if answering my unasked question.

I step in closer, mindful not to contaminate what might be a crime scene, although with the crowd and the chaos inside the apartment, I fear that ship has sailed. “David Picco thought I might be able to help. He’s outside in his truck.”

That got me a raised eyebrow, and this response. “I’ll meet you both at your office in 15 minutes.”

* * * *

I take a quick look around. The apartment is a mess—but not from efforts to save the young man lying dead on the floor. Dirty dishes overflow the sink and the counter and have made their way into a small living area that includes a Formica dining table with mismatched chairs and a sea-green sofa with purple cushions and two bed pillows. I realize for the first time that there is a young man on the sofa. He is so still I didn’t see him until now. The first thing I notice: he’s breathing.

“Doug Brumal,” I say by way of introduction. I’m now standing in front of him. He’s Caucasian and I’d guess around 6’1” and 140 pounds. He’s lean—and he’s nervous. This could simply be the aftershock of seeing someone die, someone I presume who may be close to him. The young man nods but barely looks up.

“I’m the police chief,” I add. Now that gets me a response. Mr. Lean with the Save Our Planet T-shirt looks up quickly and seems to spasm. Again, I’m not sure if this is shock or something more. “Jakob,” he says. “But everybody calls me Peanut.”

I hear a not-so-subtle cough behind me. I take a quick look at my watch. There’s ten minutes left before Kari descends on the police station. I head for outside and fill David in. Like most Inuit I know, he has been waiting patiently and without impatience. “What do you think?” he asks.

“I think there is a dead man on the floor and something Kari wants us to know,” I say. Frankly, it’s all I’ve got at this point.

We stop at the only Tim Horton’s in Iqaluit on the way back to my office and stock up on coffee for everyone. I jokingly ask the server if she has an extra coffeemaker she could sell me. The joke falls flat, although I get a polite smile. Inuit must think people from the south are strange.

We’re met with a rousing round of applause when we enter the station. That’s for the coffee and the box of Timbits. I’m on my third bite-size doughnut when Kari marches in. “Thank god,” Iqaluit’s coroner says. “I’m starving. Death has that effect on me.”

A southerner from Calgary, Kari has lived in Iqaluit for five years, a lifetime for many people who move to a place where the land is permanently frozen, the sun dips below the horizon for months, and a head of lettuce can cost you as much as $6. This is her home, but she has brought the south with her. Haven’t we all.

“Sorry guys,” she says, looking at Ahnah and my two constables, Kallik Redfern and Willie Appaqaq, “but this will have to be a closed-door meeting for now.”

Kari grabs a coffee, takes a long swallow, and lets out a big sigh. “Guys, this might be a mess. A big mess.”

We wait for her to continue. I want to dive in and ask, “What might be a mess’?” “What do you mean by mess?” “Why are we discussing this behind closed doors?” But I have learned a little forbearance since moving to Nunavut six months ago. The Inuit are a thoughtful people. They don’t jump into conversations, interrupt, or even respond immediately. They reflect, if only for several vital seconds.

Kari takes another swallow. Her 5’3” frame seems to deflate a little. “I think the kid died of benzene poisoning.”

It’s clear from the expressions on David’s face and my face that we have no idea what this pronouncement means. That confusion is quickly replaced with concern. “Benzene is a petroleum-based chemical,” says Kari. “The last water test results from the chief medical health officer showed concentrations six hundred times higher than the maximum set in the Guidelines for Canadian Drinking Water Quality.”

“Shit,” David says quietly.

Water issues have been contentious and ongoing in Iqaluit, but they have not been fatal. Until now. “Are you sure?” I ask.

“Not in the least,” says Kari. “I won’t be sure until we get blood results back from Edmonton.”

“You can’t test here?” David asks quickly. Having to ship blood cultures 2,800 kilometres away takes time and wastes time. It also increases the number of people privy to what is being tested.

“No,” says Kari. We accept her answer. The coroner knows what is at stake, and she knows what resources are available in her field here. In a small community that is closer to the north pole than to a major city, resources can be hard to come by.

“What makes you think it’s benzene?” I ask, hoping we might find a flaw in Kari’s reasoning.

“The symptoms the paramedics witnessed—vomiting, abdominal pain, convulsions,” Kari says. “He also smelled sweet.”

She sees our uncertainty. “Benzene has a sweet smell.”

“This isn’t good,” says David. You can see the concern etched on his face. “I need to contact the environmental health officer and fill them in. Then we’ll need to inform the city council and the government executive.” In Nunavut, the territorial government is run by consensus. Decisions do not have to be endorsed unanimously but they must be carefully thought through and presented. The member from Rankin Inlet is in for a long few days, maybe weeks.

“Doug, will you dig up everything you can on this young man, and keep me apprised,” David adds as he makes his way to my office door. “Kari, please push for the blood results.”

* * * *

There are only a few hours left in the work day, and my team is in full swing. This is new to us. First, almost everything is new to us. The Iqaluit Constabulary has officially been up and running for fewer than three months. Second, we usually investigate what is a suspected crime, not a suspected accidental death.

The young man now has a name: Erik Whetton. What we know so far is that he’s 27, originally from Bakersfield, California, and has been living in Iqaluit for the past six months. Willie is reaching out to the deceased’s family for further background. Kallik is going through the apartment, taking photos and samples, as appropriate. Ahnah and I are meeting with the roommate/lover/husband in 40 minutes.

Jakob Brandt is prompt. Ahnah has made the interrogation room as friendly and welcoming as possible. The lights are not on full beam, there is bottled water on the table, and biscuits I suspect were a treat for me from Kallick’s mom. It’s not usually my style to jointly interview suspects, witnesses, or others, but somehow Ahnah has become integral to this process. I’m not sure how this happened; I suspect Ahnah knows exactly how it happened.

Brandt lowers his lanky frame into one of the three metal chairs in the room. He overflows the back of the chair and his legs protrude almost to the edge of the table in front to us. Today his T-shirt says, “Save the whales.”

“Thanks for coming, Jakob,” I say, trying to sound friendly. I’m actually trying to be friendly. It is a technique I’ve learned from the Innuit, but to them it is not a technique.

“Peanut,” says the lanky man with the long legs. “It’s Peanut.”

I can sense Ahnah’s confusion. She’s trying to take notes but a grown man with the name of a snack food makes no sense to her. It’s something I’ll try to explain later, although I’m not sure how. “We’re trying to find out what happened to Erik,” I explain, “and hoping you can help.”

“I’ll try,” says Peanut. It’s more of a mumble. Again, not sure if he’s nervous or shy. Or something else.

“We have the report from the paramedics,” I note. “It indicates you called fire and emergency.” Iqaluit does not have a 911 system.

Peanut nods. He obviously does not want to relive this moment, but to his credit, he sits taller and says, “We were working on some stuff. Erik got up to get a glass of water. A couple of minutes later he’s flailing on the floor, throwing up, and clutching his stomach.”

“Do you have any idea what happened?” I ask.

“Whatever it was, it killed him,” Peanut says. So the young man has an edge.

“What were you working on?” I ask.

Peanut looks surprised. “What do you mean?”

“You mentioned you were working on ‘some stuff.’ I’m wondering what that might be.”

It turned out to be stuff Peanut is passionate about. It appears he was not alone in that fervor. I have a friend who contends there are three types of people who are drawn to the northernmost territory in North America: mercenaries, missionaries, and misfits. Whetton appeared to fall into the second category, or at least a sub-category. A staunch environmentalist, Whetton, Peanut tells us, came to Iqaluit to work with a non-profit group named Nuna Anaana. Their focus is on climate change, specifically permafrost degradation and increased coastal erosion caused by the late freezing of sea ice.

“You know a lot about this,” I say by way of making conversation and making Peanut feel at ease. I need to learn more, then I can figure out what is relevant and what isn’t. Ahnah tilts her head and gives me a quizzical look. I’ll explain later.

“I’m an environmental engineer,” says Peanut.

“What was Erik’s background?” I ask.

“He just cared about the planet,” says Peanut. There is a hint of defensiveness.

“Were you two roommates, or friends, or…” I let the sentence dangle.

Peanut sighs. “We’re both straight. We’re friends, and we’re broke. We lived together to save money and because we like each other’s company.”

“So let me get this straight,” I say, switching gears abruptly, “Erik takes a drink of water, then he dies.”

Peanut is sitting up straight now. Can’t tell if he’s miffed or anxious. “Well, it wasn’t quite that quick, but close enough.”

“You think he died because he drank the water,” I say. I can feel Ahnah flinch.

“I do,” says Peanut. “That water has been killing people in this community for decades. It just usually takes longer.”

Indeed, it does.

* * * *

I spent a restless night. Listened to a little Elvis and opted for a Jack Daniel’s. Neat. It’s a little past eight a.m., and my office door is closed. Again. Inside are David, Kari, me. On the table is hot coffee and two equally hot issues. Jakob Brandt has gone to the local paper to discuss the untimely death of his friend, who is described as an avid environmentalist whose mission in life was to make the planet healthy and safe for all living creatures.

We knew the story was coming out. A reputable, indeed award-winning, newspaper, the Nunatsiaq News reached out to confirm Brandt’s allegations before publishing. Municipal officials are quoted in the piece, as is Kari.

What wasn’t anticipated was the life or the reach of the story. Frontpage news and social media fodder here, the story has become a national story. Media attention from outside the territory is unusual and often unwelcome, at least for the government.

David drops the paper on the coffee table. “Nothing we can do about this. It’s not going to go away until we deal with the problem.”

That brings us to the second issue. Kari has the blood results. Whetton’s blood has a benzene level 1,200 times above the recommended maximum.

“I’ve never heard of anything like this,” says Kari. She’s looking frazzled. Wisps of her curly brown hair protrude at unusual angles, and there are circles under her eyes that weren’t there the last time we met behind closed doors.

“Is it the water?” David asks.

“What else could it be?” Kari replies.

“Let’s find out,” I suggest. Two faces turn to look at me in confusion. “Let’s test the water.”

“That won’t help us,” says Kari. “We’d need to test water from the day Erik Whetton died. Benzene levels fluctuate.”

“Would it help us to test Peanut’s blood?” I ask. “He and Whetton lived in the same apartment, drank the same water. Surely his levels should be elevated.”

“We could do that,” Kari agrees, “but where does it get us. If his levels are high, it only means he got lucky or didn’t drink the apartment water on that day.”

“Why would the levels be so much higher in one part of town than another?” David wonders. I’m not sure if he’s talking to us or to himself.

“The underground tank leaked fuel unevenly. Some areas are more contaminated than others, and because it’s in the groundwater it’s hard to predict where levels are highest or how the treatment plant is adding to the issue,” says Kari.

“Still,” she adds almost as an afterthought, “no one else has died from benzene poisoning that we know of. I checked with the hospital. No one is even diagnosed with this. Of course, we also weren’t looking for it.”

“Are we saying this might not be accidental?” I ask.

David and Kari look at me in surprise. “What do you mean?” David says at the same time Kari asks, “How could it not be accidental?”

Now I’m thinking like a cop, not a supportive friend and colleague. “Let’s just focus on what we know and see where it leads us.”

Here’s where we end up. Erik Whetton died of benzene poisoning, of that there is no doubt. Where the doubt creeps in is whether he died by drinking tap water himself or at someone else’s hand. If it’s the latter, it’s murder.

* * * *

There is really only one suspect: Jakob Brandt. It takes Kallik less than an hour to find a credit card receipt for the purchase of benzene, which we discover is easily available online for lawful purchase. Credentials are required, however, and Peanut has these. He’s an environmental engineer. And right now he’s sitting in our interrogation room.

Ahnah has made sure there are no niceties this time. The camera light shines a steady red glow on the stainless steel table. Ahnah is on one side of the table taking notes, even though the interview is being recorded. I’m on the other side, next to Peanut, the better to see his movements and his reactions.

“There’s been a development,” I say without preamble and toss a copy of the credit card receipt on the table.

Peanut looks at it and cannot hide the recognition in his eyes—or the implication of what he’s looking at. “You bought benzene,” I say, “and your friend died of benzene poisoning.”

“So what?” Peanut says. He tries to sound full of bluster. He fails.

“You can connect the dots,” I respond. “You’re bright, and you’re in a lot of trouble unless you can explain this purchase.”

“I was conducting some experiments on benzene in soil,” Peanut says. “I have my notes to prove that.”

“What will the notes prove,” I want to know.

“I’ve accounted for all the benzene I’ve purchased. I did not kill my friend,” says Peanut. He stands up. “We’re done here.”

* * * *

It’s been two days since Erik Whetton died. The whole Iqaluit Constabulary—all four of us—are in the station meeting room. There’s a whiteboard, which is very white at the moment, a fresh pot of coffee, and homemade bannock, compliments of Kallick’s grandmother. There is also molasses, but it is not getting a warm reception. I’ve encouraged my team to try this on the traditional deep-fried bread, but it is not catching on as a taste treat here. Ahnah has put some on her plate to be polite, but she is making sure to keep her bannock as far away from it as possible.

We take time for a few bites, a slurp or two of coffee, and some pleasantries before we dive in. Peanut has buried us in data and documentation, most of it indecipherable squiggles on paper and spreadsheets that spread in all directions. We’re each taking a stack, making notes, and passing our stack to the person on our left when we’re through. Three hours later we put on a fresh pot of coffee—Willie has brought his coffeemaker from home—and settle in for a review.

As far as we can tell, Peanut has accounted for all of the 500 ml of benzene he purchased legally from a lab in Arizona. The chemical, it appears, was used in soil samples to assess evaporation levels and absorption rates and reach.

“We don’t have much soil,” Ahnah points out. “Why spend all this time and effort examining benzene in soil?” It’s a good question. In Nunavut, most of the land is tundra, which means it is bare, rocky, and treeless. And it is also locked in permafrost. Only a few inches of soil subsists in parts of the region.

Willie writes Ahnah’s question on the board and puts it in a column under Peanut’s name and Kari Frost’s name. “Even if he used the benzene in the soil like he said, could he then have put the soil in water and given it to Whetton?” Willie asks. “That way he would account for the benzene he bought.”

“Would you drink dirty water?” Kallick asks. Still, Willie puts the question under Kari’s name. “Could he have faked the numbers?”

That is the key question. I feel a surge of pride at how far this team has come and how quickly. “Either Peanut used the benzene as he documented, he fudged the figures, or there is another source of benzene,” I say. “Let’s check with Kari.”

As if on cue, the coroner walks through the door. I look at Ahnah. “I texted her when we began,” she says quietly. Of course, you did.

Kari spies the bannock—and the molasses. “Oh my god. It’s been so long since I’ve had molasses on my bannock.” My team looks at her like she has two heads. Kari doesn’t notice. She piles a plate high with bread and drowns it in the black syrup. We wait while she eats—and reads our no-longer-white board.

“I can answer your questions, but I’m not sure if it helps,” Kari says. We’re informed that Iqaluit’s water treatment plant sits on a bed of contaminated soil, so Peanut could have been investigating the impact of benzene on groundwater. The benzene in the soil could have been dissolved in a glass of water but this would be time intensive and result in a very dirty liquid. Even though people in Iqaluit are used to water that smells funny, brown water is not the norm. In fact, many people don’t even drink tap water.

The last question is the most problematic: is the data genuine. “I don’t have expertise in this area, but what I’m reading in Mr. Brandt’s notes appears complete and authentic,” Kari says.

“So we have a dead man and no suspects,” I say, more to myself.

“Or you have an accidental death caused by benzene in the drinking water,” says Kari.

“We’re back to where we started,” says Ahnah.

“Then we start over again,” I say.

* * * *

The best place to start over is with Peanut. This time I head to his place. Ahnah asks if she can tag along. Peanut doesn’t seem surprised to see us, more resigned.

“What do you want?” he asks.

“To find out why your friend died,” I answer. That seems to dispense with the attitude. Well, almost. Peanut invites us in and offers us a glass of water. We decline.

“Your research is impressive,” I say. Lying.

“How would you know?” Peanut counters.

“Coroner,” I say simply and wait a few seconds. “I’m trying to figure out why Erik got sick from the water and you didn’t.”

“I drink bottled water,” says Peanut. “Erik refused to. He said bottled water wasn’t affordable for everyone and it deflected us from the real issue—that the water here is contaminated.”

“He sounds committed to the cause,” I say, more to keep the conversation going.

“More than anyone I’ve ever met,” says Peanut. “Erik believed we were killing the planet and nowhere faster or more profoundly than in the north. He dedicated his life to fixing that.”

I asked Peanut a few more perfunctory questions and got the expected answers. Ahnah and I thanked him and headed for my truck. “What did you think?” I ask her. Our executive assistant is insightful and reflective.

“I believed him,” she says.

Me too.

Ahnah hesitates a second, then asks. “Is there anything you’re willing to die for?”

Damn it. There it is, the thing that has been eluding us. “We need to go back,” I say turning quickly and heading into Peanut’s building. If he’s surprised to see us back so quickly, he doesn’t show it. Just shrugs and ushers us in.

“What kind of friend was Erik?” I ask without preamble.

Now Peanut does look surprised. “What do you mean?”

“Would he ever hang you out to dry?” I ask. “Let you take the blame for something he did?”

“Never,” says Peanut firmly and quickly.

“We need to search your apartment if that’s okay with you.” Peanut nods his assent. I turn to Ahnah. “Can you get Kallick and Willie over here.”

“I’ve already texted them,” she says. Of course you have.

* * * *

I explain to the team that we’re looking for the equivalent of a suicide note. Something that will make it clear Peanut did not harm his friend and his roommate. Three blank stares greet my request.

“This is part process of elimination,” I explain, “and part profiling. It’s unlikely drinking tap water killed Erik. We’ve never had levels that high, and no one else died that day. No one even got sick. So that means this was deliberate. Someone needed access to benzene and Erik Whetton.”

“That’s Peanut,” says Willie, “but we ruled Peanut out.”

“That leaves us with only one suspect,” I say.

“He killed himself,” says Ahnah quietly.

“Why would he do that?” Willie asks.

“Because no one was taking the water issue seriously,” says a voice in the background. I had almost forgotten Peanut was here, sitting quietly on the couch. I suspect that was a role he often played with Erik Whetton.

“Could Erik have taken some benzene out of your container and replaced it with water?”

Peanut nods. “He wouldn’t need much, and a little dilution wouldn’t be noticeable in my work.”

“But he would know, or at least assume, that you could be blamed for his death,” says Ahnah. We all turn to look at her. I can’t help but smile.

“Suicide note,” I say, and we dive in. Couches and chairs are pulled apart, vents are opened, ceiling squares are removed, and mattresses upended. After forty minutes, I hold up my hand. “We’re going about this all wrong,”

My team, which for now also seems to include Peanut, looks at me. In Humboldt, we call this the look of a deer in headlights. “We’re searching for something that would exonerate Peanut in case he was ever accused of killing his friend. Whetton wouldn’t have made it almost impossible to find. It has to be somewhere obvious but not obvious.”

Peanut nods. “Erik had a great sense of humor. Maybe it was because his work was so heavy, but he loved to laugh.”

“Water,” I say. “It has to have something to do with water.”

“What’s funny about water?” Willie wants to know.

“Funny ironic,” says Ahnah. Some day this woman will be police chief.

“What was in the freezer?” I ask.

We take inventory: four frozen dinners, two caribou roasts, one serving of char, a water bottle, two containers of ice cubes, and one bedraggled ice cream container. The frozen dinners appear intact, but we open them anyway. Nothing. The ice cream container is immersed in hot water. Still nothing.

“What’s in the water bottle?” I ask.

“Water,” says Kallick. He tries not to smile. “Ice actually.”

“Melt it,” I say. In the middle of the small water puddle that results sits a clear plastic tube with a lid. (Both made of recycled material Peanut tells us.) Inside is a thumb drive.

We won’t know for several hours exactly what’s on the thumb drive, but we all know what’s on the thumb drive. Erik Whetton’s last act in life—before giving his life to help save this community and this planet—was to protect his friend.

Peanut is in tears. He reaches for the bottle, and I stop him. “We’ll need to keep this for evidence. At least for a little while.”

“Read the bottom,” he says.

There in black letters is the brand name of the bottle manufacturer: Water Protector.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

donalee Moulton is a writer based in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Her short story “Swan Song” was one of 21 selected for publication in Cold Canadian Crime, an anthology published by the Crime Writers of Canada. Her first mystery novel, Hung Out To Die, is being published this spring [2023]. donalee is also the author of the new book The Thong Principle: Saying What you Mean and Meaning What you Say and co-authored Celebrity Court Cases: Trials of the Rich and Famous.

A DEATH IN THE DEPARTMENT,by Hal Charles

The college’s bell tower tolled midnight as State Police Detective Kelly Stone slipped on her latex gloves and entered the third-floor faculty office of the victim, Professor Harold Sweetwater. The head of the figure that slumped over the desktop computer keyboard had been clearly bashed in from behind. Lying on the floor were a pair of broken glasses and a blood-covered 2004 baseball bat commemorating the Red Sox’ first World Series win in almost a century.

“Think it was a disgruntled Cardinals fan with a long-time grudge?” said Assistant Coroner and CSI Jackie Bowdoin, who was dusting the computer keyboard just beneath the professor’s head.

Recognizing the gallows humor common to the profession, Kelly said, “Possibly, if one of the three suspects rooted for St. Louis.”

“Got it down to only three possibilities already?” said Jackie. “That’s fast work.”

“While giving you first shot at the crime scene, I’ve been down in the security room checking tonight’s video.”

“If they’ve got video of this office, then this murder is solved,” said Jackie, standing up.

“Not really. After 5:00 pm, the only possible entrance to the faculty office building is the front door, and there is only a camera there. Tonight is Sunday with slow traffic, and just three people carded in after Sweetwater.”

“Maybe the perp came in earlier and waited for the good professor,” suggested Jackie.

“Not possible. Everyone who carded in this weekend after the usual Friday night sweep also carded out.”

“What was Professor Sweetwater even doing here?” posed Jackie.

“Meg, the security guard who helped me with the video, said the professor was a famous scholar who liked to come in on the weekends because nobody was around to bother him.”

Jackie picked up some journals piled on Professor Sweetwater’s desk. “Listen to these articles by the professor. ‘Classical Allusions in John Cheever’s “The Swimmer”’ … ‘The Structure of Browning’s “Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister.”’

“The guy sounds brilliant,” admitted Kelly.

“So who are the three suspects?” pressed Jackie.

“All members of the English department. Professor Kate Posey, a poet; Kailey Layne, the professor’s Teaching Assistant; and Melanie Sonata-Sweetwater, the professor’s soon-to-be ex-wife. According to Meg, who’s a bit of a gossip, Kate the poet is a bitter rival of Professor Sweetwater, who thinks she’s the better writer.”

“A promising suspect,” said Jackie.

“Kailey might be better. Meg thinks the two had an affair that the good professor just called off and Kailey wanted it rekindled.”

“A traditional academic trope,” commented Jackie.

“Melanie might be the best suspect,” said Kelly. “Meg says that she, hating the impending divorce, was trying to win him back by bringing him food during his weekend writing binges.”

“I didn’t notice any food around, but there is lipstick here on the professor’s collar. Maybe what Melanie brought him was fury as in ‘Hell hath no fury like a woman scorned.’” Jackie pounded her fist on Professor Sweetwater’s desk to make her point, and as she did, the computer suddenly came to life.

“What’s that?” said Kelly, pointing to the lit screen.

“Looks like some sort of esoteric article,” assessed Jackie.

“No,” said Kelly. “I mean what are those nine characters about four lines below the last paragraph on the monitor?”

“Y85 G6 28R3,” read Jackie. “It looks like a Social Security Number with some letter substitutions…as in a code.”

Kelly stared at the screen, then said, “Ah ha! I believe we’re looking at a dying declaration wherein Professor Sweetwater named his killer.”

“Who?” said Jackie.

SOLUTION

Kelly immediately arrested Melanie Sonata-Sweetwater, who, surprised at being caught so quickly, immediately confessed. When she had stopped by with a basket of food for her ex, she said she saw him through the window kissing Kailey. Enraged, Melanie waited until Kailey left, then snuck into his office and bludgeoned him from behind with his favorite baseball bat. Why did Kelly suspect Melanie? Dazed, his glasses on the floor, and feeling his life leaving him, Sweetwater tried to leave a dying clue. Unfortunately, in his last moments, instead of placing his eight fingers on the keyboard’s home row, he put them on the row above. Therefore, with his left digits on QWER and not ASDF, and his right fingers touching UIOP and not JKL, he typed Y85 G6 28R3 when he meant to write HIT BY WIFE.

The Barb Goffman Presents series showcasesthe best in modern mystery and crime stories,

personally selected by one of the most acclaimed

short stories authors and editors in the mystery

field, Barb Goffman, for Black Cat Weekly.

THE WIZARD OF PAWS,by Karen Cantwell

My name is Barbara Marr and, by all outward appearances, I am a typical suburban mother. Upon closer historical scrutiny, however, one will learn that my life is anything but typical. For one thing, I seem to stumble upon more dead people than is statistically probable. And trust me, I do not go out of my way to find these corpses. I have also been abducted by criminals several times. Then last month, a number-one-trending hashtag #ThatBarbaraMarr propelled me into the social media spotlight while I tried to unravel the mystery of who killed a man known as Pickle.

See? Not typical.

So I suppose it wasn’t outside the realm of possibility, then, that a simple trip to the veterinarian would turn into something so bizarre that it felt more like a dream than real life.

Was it a dream? Well, let me tell you how it all started…

* * * *

Looking out from my kitchen window I noticed a storm brewing on the horizon. Heavy gray clouds darkened the western sky.

Indoors, my cat, Indiana Jones, was not happy. I suspected he wasn’t very healthy either. He moaned loudly from the tight confines of his cat carrier while I poured coffee into mugs for my friends Roz Walker and Peggy Rubenstein.

The three of us sat around my kitchen table on a school-day morning. Roz and Peggy had come to keep me company while I worried about my poor Indy, who yowled in pain every time he tried to pee.

“When is your appointment with the veterinarian?” Roz asked.

I looked up at my kitchen clock. Forty minutes to go. “Ten thirty.”

“What vet do you use?” Peggy asked.

“We haven’t been happy with ours, so I’m trying that place on Rustic Woods Parkway—Yellow Brick Road Pet Clinic.”

“Dr. William Oz,” Peggy said. “But he died last month. I know his ex-wife, Weslea Green.”

“I’ll one-up you,” Roz said. “I know his widow, Dorothy. She’s in my yoga class. She’s a veterinarian too, in the same office.”

I nodded. “That’s who we’re seeing today. I couldn’t believe it when the receptionist told me we’d be seeing Dr. Dorothy Oz.”

Roz stood and rinsed her cup in the kitchen sink. “They used to call Bill ‘The Wizard of Paws’ because he had such a way with animals.”

“I hope his widow has the same gift, because Indiana Jones is a very trying patient.”

“I’d stay longer, but I have to get to the copy store,” Roz said. “Good luck with Indy. I hope he’s okay.”

Peggy drained her cup with one more gulp. “I have to go too. I’m volunteering at the school this morning.”

As they were leaving, Roz reminded us to meet at her place later in the day to help her fold pamphlets for the PTA. Were we excited to be folding pamphlets for the PTA? No, but we were always happy for a chance to chat. Plus, she’d already promised to serve her Yummy Tummy Crab Puffs.

* * * *

By the time I arrived in the parking lot of the Yellow Brick Road Pet Clinic, the brutal storm was upon us. Gale-force winds whipped me around as I struggled to pull open the door with one hand and keep hold of the cat carrier with the other.

Disheveled, I took a seat in the colorfully painted waiting room and placed Indy’s cat carrier on the floor by my feet. On a wall beside the front desk, a framed photo of a smiling gray-haired man was prominently displayed. Below the frame a plaque read, It is with great sadness that we inform our clients of Dr. William Oz’s passing. He was a beloved husband and true lover of all animals, large and small.

An older woman two chairs over thumbed through a magazine while her Chihuahua shivered in her lap. The woman apparently became bored with the magazine and set it down, turning her attention to me instead. She peered at me through pink plastic-framed glasses. “Sad, isn’t it?”

“You mean about the doctor?”

She nodded.

“Yes,” I agreed. “Very sad.”

Indy yowled, causing the tiny dog to shake even worse. The woman scooted over one chair, positioning herself directly beside me. She scanned the waiting room with wary eyes like she was some secret agent in an Alfred Hitchcock film. “Did you hear the cause?” she asked me.

“No.”

“They’re saying heart attack.” She arched one eyebrow. “I’m not buying it.”

“Did he have heart problems?”

She shrugged. “Don’t know. But I don’t care. I think she did it.”

“She?”

“The wife. The young one.”

“You think she gave him a heart attack?”

“No. I think she killed him.” She ran a finger across her throat like she was slitting it.

“Was his throat slit too?”

“No, of course not.”

I decided the poor little dog probably had good reason for being so high-strung. His owner was obviously a nut case. I pondered for a moment how to respond but was saved by the veterinary technician who emerged from an exam room with a smile. “We’re ready to see Munchkin now.”

Upon hearing his name called, Munchkin practically spasmed himself to death. The old woman rose slowly while talking in soothing tones. “It’s okay, Munchie, sweetie, you’re not seeing that mean lady doctor. The nice man is going to examine you today.”

I wondered if there might be some odd contractual clause that, in order to use this clinic, clients must name their pets in the Wizard of Oz theme.

After Munchkin and his owner disappeared into the exam room, I asked the receptionist, “Who is the nice man she’s talking about?”

“Dr. Oz hired a new vet. He just started on Monday.”

“How is she doing, by the way?”

“As good as can be expected, I think,” the young woman said. “She stays very busy. I think it helps.”

“She’s not mean, is she?”

The receptionist laughed. “Not at all. Indiana Jones will love her.”

Moments later we were ushered into an exam room, where the veterinary assistant, a young man with a beard and a tattoo, weighed Indy and took his temperature. I make that sound like it was easy. It was not. There was yowling and hissing and claws emerging. And that was just the vet tech.

When Indy was done, I held him, stroking his coat and giving him kisses. Then Dr. Oz pushed through the swinging door. She didn’t look mean. She greeted us with a surprisingly joyful and pearly white smile. Her shiny chestnut hair was pulled back in a simple ponytail. Her brown eyes twinkled. She did not appear to be a woman who had just lost her husband to an unexpected heart attack. In fact, she didn’t look old enough to have a husband who just died of a heart attack. From his picture, the late Dr. Oz appeared to have been in his sixties. This woman was easily twenty years his junior, if not more.

She extended her hand. “Hi. I’m Dr. Dorothy Oz.”

“I’m Barbara Marr. Please tell me you’re not from Kansas.”

She laughed as we shook. “Tell me what’s wrong with Indiana Jones.”

“He can’t seem to urinate. When he tries, he just screams.”

Always the drama cat, Indy yowled long and low.

“Poor little guy,” she said with sincere sympathy. “Let me take a look.” She moved to take him from my arms.

“Word of warning: he doesn’t like most doctors.”

“Oh, I think we’ll get along just fine, won’t we Indy? Can I call you Indy?”

Apparently, Mrs. Dr. Oz was as good with animals as her late husband, because she won over my surly feline with the magic of a cat whisperer.

* * * *

A couple of hours later, I was helping Roz and Peggy fold pamphlets at Roz’s dining room table.

“So, Indiana Jones has to spend the night at the pet clinic,” I said, creasing a piece of paper.

“What’s wrong with him?”

“Blocked urethra.”

They both cringed.

“Yeah. The doctor will actually put him under to, you know, unblock him. Then keep him overnight to be sure he’s okay.”

“How was Dorothy?” Roz asked.

“In good spirits, I have to say.”

Peggy finished folding a pamphlet and set it on a growing pile. “She’s young and pretty, right?”

“I’ll say. She looked like she stepped out of a shampoo commercial.”

“He left his first wife for her, you know,” Peggy said with a sneer. “That’s what these men do. Their wives get a few gray hairs and they dump them for some young chippie. Breaks my heart. I told Simon if he ever does that to me, I’ll go Lorena Bobbitt on him.”

I laughed. “Speaking of violence against men, this crazy woman in the waiting room tried to convince me that Dr. Dorothy actually killed her husband, even though he died of a heart attack.”

“Can you kill someone and make it look like a heart attack?” Roz asked.

I shrugged. “I don’t know, but I doubt the woman had all of her marbles anyway. The doctor charmed Indy as if by magic, so I’m happy. I mean, not happy the man is dead. But happy his wife is good with animals.” I paused, thinking. “She did seem awfully cheerful for a woman who’d just lost her husband. Yet, she told me she’s taking off next week to fly to Paris and spread his ashes over the River Seine because Paris is where they spent their honeymoon. They must have really been in love, age difference or not.”

Peggy stopped folding to grab a crab puff from the snack tray Roz had set out. “She had him cremated? That’s strange.”

“Why is that strange?” Roz asked.

“He got the burial plots in the divorce from his ex, Weslea. That’s all she talked about for at least three book groups. To be fair, she got just about everything else. The house, the cars, the Netflix account. But she was really irked about those burial plots.”

The crab puffs were too tempting. I snatched another one. “So they had burial plots, but she had him cremated. That does seem a little odd.”

Roz shook her head. “Not so odd when foul play is afoot. Don’t you remember that story about the woman in Pennsylvania who poisoned her elderly father? She had him cremated right away to hide the evidence. That was big news about six months ago or so. She wanted the inheritance money, and apparently he wasn’t dying fast enough for her. It was really sick.”

The news story was vaguely familiar. “Maybe Dorothy Oz got an idea from the news, huh?”

“We might have our very own news story here in Rustic Woods,” Peggy said, wiping her hands on a towel and grabbing another piece of paper to fold.

“But it doesn’t make sense,” I argued. “He died of a heart attack. How do you kill someone and make it look like a heart attack?”

We pondered that dilemma for a moment, each of us sipping our lattes. Roz brightened with an idea. “She’s a veterinarian. Veterinarians euthanize animals. Maybe she euthanized him?”

“Yikes,” Peggy said.

Yikes was right. My phone buzzed with a reminder. “Oops, gotta go, ladies. I need to pick the girls up from school so I can take them to the dentist. A day of doctor visits.”

“Are you going to explore this murder theory some more?” Peggy asked.

“I’d better not. My history isn’t good. If she did kill him, and I was on her trail, she’d probably kidnap me, and you guys would probably be with me when it happened, and we’d all almost get killed. You know, the same ol’, same ol’, and who wants that?”

“Good point,” agreed Roz.

Peggy gave me a wave. “Let us know how Indy fares with his surgery.”

“Will do.” I popped another crab puff into my mouth and headed off to pick up the girls.

* * * *

Just before dinner I received a call from the pet clinic. Indiana Jones had come through his procedure without complications. He was awake, a little groggy, but doing fine. They’d call me with another update in the morning and let me know when I could bring him home.

I’d barely set the phone down when a text from Peggy buzzed in. Dancing Danny, it read. The message made no sense to me at all, but that wasn’t unusual when it came to a Peggy communication. She had a very indirect way of telling a story.

I texted back. What?

Dancing Danny. I told you about him.

I read her response and for the life of me, couldn’t remember her telling me about anyone named Dancing Danny, but she had so many wild stories about friends and distant relatives, it was hard to keep them all straight. This was too much for a texting conversation.

I dialed her number, and she picked up on the first ring.

She started right in. “Dancing Danny. My cousin from Nebraska. Although he’s not really my cousin, he’s just one of those people your family knows really well and so you call them a cousin because you practically grew up with them. His dad was named Danny, so he’d be Danny Junior, except that Danny’s other two brothers were named Danny too, so we call them Dancing Danny, Deaf Danny—although he’s not really deaf, he just doesn’t listen so it’s kind of a joke—and then there’s Demented Danny. He went missing five years ago. Kind of scary.”

“Why do I care about Dancing Danny?”

“His third wife’s daughter-in-law has an ex-uncle who is a retired veterinarian. Rudy. Funny guy. I met him at a funeral.”

“And…”

“So I called him up, and I asked him if a veterinarian could use euthanasia drugs to kill someone and make it look like a heart attack.”

“What did he say?”

“He said not likely.”

“Then why are you calling me about it?”

“Because he said there’s a better way: potassium chloride. Too much will stop a person’s heart. So, Rudy says, if this Dr. Mrs. Paws Wizard lady wanted to kill her husband without raising suspicion, she’d just have to inject him with enough potassium chloride and boom. Dead.”

“Why wouldn’t it raise suspicion?”

“Doesn’t show up in the blood. And Rudy also said if the guy had a documented heart condition of any kind, even better, because then, as the wife, she could easily decline an autopsy, ask for the cremation to cover her bases, and never be suspected.”

* * * *

Roz had news for me at the bus stop the next morning. “Guess who I saw at Winston’s last night? Dorothy Oz.”

A cold wind blew through my very bones. I zipped my coat up. “Winston’s. Pretty fancy. I assume she wasn’t alone?”

“Definitely not alone. She was with a very attractive man. Tall, dark, and handsome to be more specific.”

“Why were you at Winston’s?”

“Anniversary dinner.”

“Wasn’t your anniversary about six months ago?”

She nodded. “We celebrated last and next anniversary at the same time. We call it efficient romance.”

“Speaking of romance, did it look like passion was brewing between the doctor and Mr. Captivating?”

“Hard to say. They were arriving as we were leaving. I will say this: she didn’t look like someone whose husband just died. She was positively glowing.”

“I know! That’s how she was yesterday. I figured maybe she was just being professional. Did she really get over her husband’s death that quickly? Speaking of the husband’s demise, Peggy talked with a retired veterinarian and learned something very interesting.”