Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Notting Hill Editions

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

For many years, photographer Michael Collins had wondered what exactly it was that he found so mysterious and compelling about photography. In this series of linked pieces, Collins offers a reappraisal of photographic genres – including the humble and ubiquitous – that he believes are worthy of greater understanding. From restoring abandoned photos, whose subjects are lost to time, to a quotidian history of the studio portrait; from tracing the origins of the photographic survey within the wider field of the history of art to an experiment in portraiture using gorillas, Collins reveals what it is about photography that is so enduringly fascinating.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 230

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

i

Notting Hill Editions is an independent British publisher. The company was founded by Tom Kremer (1930–2017), champion of innovation and the man responsible for popularising the Rubik’s Cube.

After a successful business career in toy invention Tom decided, at the age of eighty, to fulfil his passion for literature. In a fast-moving digital world Tom’s aim was to revive the art of the essay, and to create exceptionally beautiful books that would be cherished.

Hailed as ‘the shape of things to come’, the family-run press brings to print the most surprising thinkers of past and present. In an era of information-overload, these collectible pocket-size books distil ideas that linger in the mind.

ii

iii

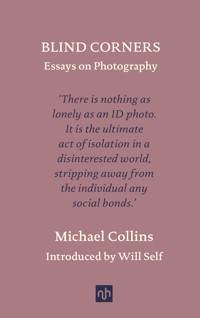

BLIND CORNERS

Michael Collins

–

Introduced by Will Self

iv

v

To Rosavi

Contents

ixWILL SELF

– Introduction –

When did it begin, this intense revulsion I feel from the specular culture of our era? I asked myself this question again … and again, at almost every page of this haunting, paradoxically elegiac collection of essays on photography. (Paradoxical, because one thing’s for certain, while photography is itself always a sort of posthumous shock: the epitaph of a moment – it isn’t going away any time soon.) While I’ve felt nothing but disgust for photography of all kinds for over a decade now, nevertheless, Michael Collins – for as long as I keep reading him, and for a considerable while after – persuades me not only of its significance as an art-form, but also of the beauty of individual photographs: indeed, that they partake of the auratic not despite the age of art’s technological reproducibility, but precisely because of it.

A decade ago, I remember beginning to have to fight with selfie-stick-wielding tourists in order to cross Westminster Bridge when walking home from the West End; it was a time when the ownership and use of mobile phones and their cameras had moved from the ebullition of universality, to some sort of boiling point: no hand was complete without a lens, xwhile those hands, hydra-like, continually bifurcated, sprouting new appendages, each with its own lens. I remember reading around that time that ‘peak photo’ had been reached, understood as that year in human history when more photographs were taken than the sum of all those taken in all preceding years. I also visited the Large Hadron Collider at CERN outside Geneva that year, and circumambulated the fifty-kilometre particle accelerator, partly above ground, and partly below – a progress that juxtaposed the scenic Jura escarpment with Alician descents into forty-storey holes, at the bottom of which I found four-storey-high digital cameras being laboriously prepared to capture – in inconceivably infinitesimal fragments of time – images of the unimaginably events this very large installation was built to enact.

For Collins – a landscape and architectural photographer, principally, whose own highly accomplished work is made using equipment that demands long exposure times – the parallax view is understandably also temporal as much as spatial; and it’s another of the great benisons of this collection that it draws disparate events in the history of the specular culture into tighter proximity as the elegant line of Collins’s prose pans past.

If peak photo was around 2015, then peak art occurred sometime in the mid-1970s. (At least, this was what was vouchsafed to me by Nicholas Penny, the art historian and onetime director of the National xiGallery.) This being understood as the year in which the total value of contemporary artworks sold at market, exceeded that of all artworks of all previous eras. Yes – I know. Staggering. Enough to shake the lens and blur one’s image of reality, such that the human figures – the commoditising Hirsts and Koons and Emins – appear as so many wormy blurs traversing the pictorial space.

Vitally concerned by the way in which the physical properties of photographs are obnubilated by their ubiquity, as an essayist Collins is a kind of modern Eadweard Muybridge; but whereas the pioneering photographer studied motion in nature (and its troubling subset, soi-disant ‘humanity’), these writings are a series of limpid prose-portraits of the technological development of photography and its impact on the collective psyche. The collection comprises notes towards a historiography of photography – placing the practice, schematically, within the overall use and improvement of reprographics – together with tentative excavations of a very personal kind of inner space.

Collins is, one feels towards the end of this collection, always the still and silent man, poised beside his own view camera – a tripod-mounted mechanism (a head-on-legs), that demands of its user a period of studied concentration, looking not through the lens but standing alongside it, as if that lens were also in some sense creaturely. There Collins is, out on the bleak Hoo Peninsula, between the Thames and the xiiMedway estuaries – or, as I prefer to think of it, the elemental Isle of Grain – waiting for the opportune moment to push the button, open the shutter, and let the full light of reality flood in.

Joseph Conrad’s Marlow told his tale of the heart of darkness aboard a yacht moored off the Isle of Grain. Collins has one to tell as well: he describes the way he and his lens interrogate the muddy foreshore of this strange faraway nearby – an expansive fretwork of creeks and muddy islets – in the process, retrieving the buried history of its curious appearance: like the virtual consuming the actual, for decades men laboured digging up the clayey mud to be made into bricks. Bricks that built the city Marlow pronounced to be also ‘one of the dark places of the earth’.

It’s out of this civilised darkness – in the story, a visible nimbus of coal smoke hanging over the metropolis to the west – that photography flashes; and while Collins doesn’t dwell on it, the medium’s claim to produce artworks rather than mere artefacts, surely rests in part on the perishability of film stock, and the breakability of the old glass negatives. Those of us who belong to Collins’s generation thought the ubiquity of the photograph would never end – the snapshots seemed to sift through the long and dull afternoons as dust does in sunbeams – but of course it did. While cash is no longer king.

With each succeeding year there are fewer and fewer physical photographs extant from the pre-digital xiiiera. It’s an unavoidable accretion, therefore, of the auratic – as it were a verdigris on the object, like the gabardine veils that seem to swag across the coastal freighter, run aground off the coast of the Isle of Wight in a forever fifties, sepia and yet more sepia still. The decent draperies of a past that Collins twitches gently apart with the tender melancholy of a bashful voyeur; for if it’s the case that every reprographic technology creates its own suspension in its viewers’ disbelief, each more faithful than the last, so it is that to understand what’s happened requires a deeper sort of fidelity to the past: a willingness to take it on its own provisional terms, rather than subjecting it to the absolutism of the present.

Andrei Tarkovsky entitled his lyrical examination of his own métier ‘Sculpting in Time’, and while Collins is working in a parallel medium, there remains a point – long before infinity – where their projects intersect. Both photographer and cinematographer view the exposure of a light-sensitive surface as fundamental to the production of images – rather than any fine-motor control, or otherwise felt, haptic praxis. Just as the optic nerve itself – like some thick hank of gooey cabling – is plugged more or less directly into the brain, so abandoning figuration by hand brings conception and execution into tight proximity. Herein lies the absolute intimacy of photography – its capacity to abide with us. Muybridge said that each discrete image itself contained a lifetime – and it feels that way, xivdoesn’t it, when you unearth the old scallop-edged black-and-white snapshot from the prolapsed old cardboard trunk at the back of the once aged – now dead – relative’s garage.

Collins duets with this dangerous douceur de la vie; a honeyed mood that forever teeters on the edge of outright nostalgia – yet doesn’t succumb. His discursive writing about the group shot of the residents of Tenby in South Wales, on Coronation Day, 1952, like his analysis of the poetics of mid-century family snapshot portraiture (Velázquez goes all Kodachrome in a welter of colloidal chemicals and pigments), is an attempt to redeem all those apotheosised moments. It was Susan Sontag who memorably – pace Nietzsche – annulled the style/content distinction in fictive prose – and it’s a different mode of this dichotomy she also identifies in photography’s elision of the objective process with the subjective act: what the lens frames will be recorded, in its entirety, right down to details that, when enhanced, become unknowable and otherworldly: data about the human condition of a finer grain and a denser weave than we can possibly feel, as if it were the nap of some long-gone Burton suit jacket, hung in a dusty wardrobe of the mind, with our numb fingers alone.

In pushing his own medium to the limit of its capacity to resolve the photograph into pure data, Collins also duets with Sontag: for he acknowledges at the same time the absolute errancy that may be xvconsequent even upon this innocent act: choosing the precise moment to open the shutter and let the right light in. He quotes the Russian saying: ‘As inaccurate as an eyewitness’ – and it’s difficult not to be overwhelmed, when we consider the history of reprographic technology as the mechanisation of lying (considered as one of the fine arts): Collins reminds us that the first camera lucidas and obscuras were used by artists such as Caravaggio who wanted to effect levels of realism not obtainable by the naked eye. His colleagues are Hooke with his Micrographia; and Descartes, that res cogitans with no belief in res extensa.

McLuhan observes that when one medium of superior efficiency – print as against manuscript copying, photography as against drawing – supplants another, for some time afterwards the two continue together, in tandem; and indeed some – monks, hipsters – may be convinced for a considerable period that nothing much has changed. But the inception of the specular technologies in the nineteenth century is of a different order – consider the wagon-wheel effect, easily witnessed using a zoetrope or magic lantern, the precursor technology to the panoramas and dioramas Collins hymns as not inchoate forms of the film camera assemblage, but nascent art forms with their own associated psychology – individual and collective – and their own emergent cultures, soon to be superseded. Which is how the world’s slide carousel turns.

The uncanny stillness and even reversal of spoked xviwheels (or, indeed, the blades of fans, or plane propellers), when stared at, establishes that human vision is, indeed – as Flann O’Brien’s speculative philosopher in The Third Policeman, De Selby, believes – composed of a series of still images that the mind flicks through, as if it were a flicker book, to create the illusion of motion. What further hypothesis – rather than mere voyeurism, à la Isherwood – is required to elide the human subject (whose consciousness can also be said to be comprised by the inconceivably rapid succession of myriad still images), with the camera? Indeed, as the camera – ‘room’ in Italian – is to the subjective consciousness, so is what McLuhan termed the ‘Gutenberg mind’, to that bound and serially interleaved phenomenon, born of the associated medium: the book.

Collins, a former picture editor on a national British newspaper, will well appreciate the way an image can be worth thousands more monetarily than any mere words; he’ll recall, as well, an advertisement for the Guardian newspaper from the 1980s that saw those paragons of the fourth estate professing themselves free from any such intent, by reason of their own deployment of the following sequence. The first photo shows a uniformed white policeman in hot pursuit of a Black man. In the believing-itself-yet-to-wash-whiter Britain of Thatcher’s willing executioners, such a cut forced this card: the Black man is perp’, to the prospective Guardian reader. But lo! The second shot is cropped differently – revealing that the viewer’s interpretation xviiof the first has, indeed, been prejudicial eisegesis: here, with a wider view, we see that both Black man and white man are in pursuit of a third man – white, of course – who is the true perp’.

How is the Black man revealed to be a plain-clothes policeman rather than a malefactor? (Not that the two are by any means mutually exclusive.) Well, the Guardian-reader-in-waiting now sees that he’s straight-edge: neat hair, jacket, etcetera; even as they appreciate – given the proclivities self-selected for by the advertisement’s subliminal message – that it’s their superior intellect and moral probity that’s enabled them to go there.

Collins avers that photography is all about content – but with this example we can see how that content encodes symbols quite as much as it faithfully reproduces images. Which is why its veridical status must be challenged again and again: if the argument is that photography relieved draughtsmanship and colouring of the burden of portrayal, then Collins resiles: for him, it’s an art form quite as able to interrogate ways of seeing as it is of merely gaping. To set a camera up in the chimpanzee enclosure at London Zoo, and have the apes photograph the humans goggling at them – as Collins did – is as much to question the notion of consciousness and its associated personhood, as it is to try and determine whether the important thing about a photograph is whether the person who took it was fully conscious of the effect they managed to produce. xviiiTrue of Niépce when he aimed his lens over the balustrade outside his dormer window. Collins wants photography to be no longer grudgingly admitted as an art form, on the grounds that its reproducibility is inbuilt – but considering the way art itself continues on its Cartesian route, collapsing all res extensa into res cogitans, as the West reaches a sort of Zeno-point of conceptual aridity, perhaps a better argument is that photography deserves to be considered the artwork of the age precisely because of this: the cybernetics of wet and hardware required for it to work.

It was also Sontag who noted that the notorious photographs of the concentration camps – showing emaciated corpses stacked like cordwood, and the survivors: living skeletons with grotesquely swollen heads – were inerrant in the extreme. When the camps were working, the process was expeditious: there were no piles lying around – just Arbeit then the ovens. That this: the testimony to the most pitiless of inhumanities still within the darkening purview of human memory should itself be irredeemably partial, is surely the only confirmation we need that photography is the medium not consequent upon, or conditional for the postmodern, but entwined in it.

A convolvulus – for in the age of motion capture, facial recognition and the ubiquitous handheld bidirectional computer-cum-camera, these technologies have twined the actual and the virtual, such that everyone sees in a glass brightly – even as they stumble in xixa dark wood. Because ‘Then came film,’ as Walter Benjamin near-phatically remarks ‘and burst this prison-world asunder by the dynamite of the tenth of the second.’ Collins might, quite reasonably, quibble with the calibration – one tenth of a second doesn’t actually correspond to any either particularly pregnant, or practicable period in photography – but not, I suspect, with the sentiment. It’s no accident that his own lens is angled towards things that will endure, while his own exposition focuses on images that already have.

Under such circumstances – all civic space a battleground, beset by the rat-a-tat-tat of skeuomorphic shutters – how can it be possible to redeem the image, and to wrest it once more from this welter? The answer is, of course, that the receiver of the image, quite as much as its taker, must abide with it. Just as all writers must be readers, so all photographers should be viewers of them. And I’m not talking about super-recognisers of their own lust, who, like those called in to help detectives sift through tens of thousands of suspects, can spot the pre-criminal on Tinder or Grinder or Whatever, who will break their heart.

Collins makes the case for photography as a revitalisation of portraiture – not its death by a billion selfies. The portraiture he wishes for, though, is ideally interpersonal: and in the amateur family photographs of the mid-twentieth century (surely, non-coincidentally, his own childhood), he finds this quality of lens and eye regarding one another with an affection at xxonce revelatory and guarded. The unique prints matter as well – yes, the negatives are still there, tucked in the opposite pocket of the wallet, but let’s face it (and face the skull in the garden at the same time), no one’s ever going to develop another print of Aunt Maisie at Morecambe Bay, August, 1964.

Except for Collins – who in abiding with these revenants, demands we, too, abide with the irrealism of these images of the past, while accepting it’s the closest we’ll ever get to the reality of perception. ‘The artist,’ McLuhan avers, ‘is an expert in sense-perception.’ On that basis alone, Collins is an artist – on the basis of these essays, he’s manifestly a writer as well.

– Coronation Day, Tenby –

The copperplate script in the tiled doorway spells squibbs in letters the size of a man’s shoe. An archetypal Edwardian shopfront with a pair of plate glass windows and a heavy glass door, Squibbs was the kind of photography shop found in almost every British town. It had a red-and-white awning and a yellow Kodak sign. Once a beacon of promise for holiday photographs, like memories of summers long gone, its colours and meaning have faded over the years. The day I visited, Squibbs was on the verge of closing; its neon-lit interior was as lifeless as a morgue. On the red baize of the main display case were two amateur flash guns, decades old with discoloured price tags. Between them lay a shiny booklet showing a colour photograph of a woman with backlit hair. Mirrored shelving lined the glazed cabinets on the walls. A cheerful girl with a pink ribbon in her hair still smiled out from the adverts for Colour Care enlargements, but the party had ended long ago. Pallid cardboard boxes presented a variety of exposure meters and flash bulbs that would never see the light of an exposure. Perfectly good cameras in greying vinyl cases languished unused, solemn reminders of yesterday’s eager 2promises. Spread around the shelves and walls were photographs of weddings, parties, children and babies, landscapes and sunsets and dogs. Old black-and-white photographs had given way to vibrant prints, the earliest of which had a magenta hue, while newer impersonal portraits with bubble-gum backdrops elbowed out the past.

The owner, Graham Hughes, was a kindly-faced man in his seventies who I’d known for about fifteen years. Gesturing towards the back of the shop, he told me about the darkroom he used to have and the equipment he had installed there, equipment which he had tried and failed to give away to a college. He showed me some postcards he had made from his photographs of local views. Shuffling through a dozen or so examples of a particular scene, he inspected his work from decades ago, each print slightly differing in brightness and contrast. The picture was of a wide, sandy beach under a billowing cloudy sky, dark headlands night-black in shadow under the glare of the sun, and in the middle foreground, tiny but discernible figures, a man and woman, out walking along the beach, struggling towards the light.

Graham Hughes, Coronation Day, Tenby, 1953

Stuck on the wall behind Graham was a black-and-white photocopy of a group photograph of about a hundred people gathered on the side of a hill. Thinking it would make an ideal gift for a friend of mine who collects group photos, I asked him whether I could buy a small print of this picture. He explained that it was 3too difficult for him to provide reprints, but took the photograph down and placed it on the counter. Photographed in bright sunshine, its details were obscured by the sooty shadows of the heavily contrasting tones. An unexceptional photograph without obvious compositional merit, the photocopy showed it at its worst. Underneath the picture, coronationday,tenby was written in biro. Graham smoothed out the slightly curled paper with the palm of his hand. ‘I took that on the golf links near Shanley’s.’ Built in 1929, Shanley’s South Beach Pavilion had a dance hall, a skating rink, an amusement arcade, a roof garden, and a cinema, which had shown the first talkie in Tenby. Graham had joined a group that tried to prevent the council demolishing the building, but it was leveled in 1981. He had 4taken the photograph on a half-plate camera,and still had the glass negative. He spoke wistfully about the range of tones that could be printed from the negative, and wished he could show me a proper print of the picture. ‘Photography was photography in those days.’

After searching through several drawers, Graham found the glass negative in a glassine sleeve. Gently holding the brittle paper in his left hand, he pinched the edge of the glass with his finger tips and carefully slid it out of its wrapper, placing the negative face down. The photographic emulsion, an oleaginous coating of black and umber and silver, covered the negative save for a thin margin of bare glass at the selvage. We both leant closer to see the light on it from different angles, looking at what lay within the reflective surface of the emulsion. Only a partial aspect of the negative image was visible at any one time, as the light caught a facet of the picture in its silver membrane, vanishing back within its depths before another aspect surfaced.

One of the corners was cracked and held together with Sellotape. There was a long scratch running along the top, and a little piece of emulsion had been chipped off. When Graham held it up to the light, we could see that the exposure had been technically sound; it would yield a superb print. I told him that I had a flat-bed scanner, which could bring out all the nuances and details, and he offered to lend it to me. After replacing the negative in its sleeve, he rummaged in another drawer for a shallow cardboard box, into 5which he carefully packed the negative. I was struck by the kindness and trust that he was showing a complete stranger, and assured him that I would take great care of his glass negative and would make a high-quality print for him. All he asked was that I return the negative to him by hand. Then, following the old procedure, he took out a ledger from under the counter and passed it to me to write down my name and address. I shook his hand and left, the shop bell dinging me on my way.

Initially, I made a low-resolution scan to give me an overview. Immediately a fuller picture emerged, the amorphous crowd blossoming into an assembly of individually distinct people. The sky, cloudless blue on the day, is rendered in a uniform tone of featureless pale grey. Such is technology, the scan highlights its flaws forensically, tearing the fabric of realism’s artifice. The scratch along the top appears as a vicious scar, accentuated by its proximity to a dark band in the sky, an effect caused by uneven development during the film’s processing. A series of faint vertical streaks transforms Tenby’s sky into a backdrop, and a nebula of blotches and circles and scratches, overlain with a constellation of black dots, swathes the grey yonder. On the grass, the chip in the emulsion pokes a white hole in the realism, interjecting antimatter into the Tuesday afternoon. Just above the cracked bottom corner, a purple stain on the grass adds alien colour, as does an inverted letter B in the top left of the sky, 6forming a yellow bundle of curves floating out of the frame.

Graham Hughes, Coronation Day, Tenby, 1953 (detail)

Sharply defined in the bright sunshine against the scrim of the sky, the crowd of people clustered together have a more pronounced presence than all of the other elements, which have a softer definition. The pallid midtones of the anaemic grass and blanched buildings consign these features to the periphery, while the ranks of residents, their place in the light affirmed by the black of their shadows, congregate in the epicentre, as they stare out at the camera in a spectrum from ebony to off-white and every shade of grey. The late afternoon sunshine rakes across them diagonally, leaving the pitch of their shadows trailing behind them in a celestial breeze. Depending on the light, photography’s realism can be unworldly, emphatic in its notation, severe in its demarcation. To the naked eye, a 7shadow is a puddle whose surface can be seen through; to a camera, in strong sunlight, it’s a fathomless crevasse. The shadows in the picture head off to the top right corner, where the knoll ends precipitously with a fringe of stubbly grass and nothing but blank grey. On the left-hand side of the picture, the buildings and trees ground the scene in everyday life, but the emptiness of the opposite corner is as vacant and unnerving as the horizon on the moon.

Crowning the left side of the hill, Shanley’s western façade faces the afternoon sun. Running along the upper floor of the turn-of-the-century building, a row of closely spaced windows keeps watch on the events below. Further along to the left, standing slightly behind its dominant neighbour, sits a squat concrete building with a castellated roofline, its incongruity mocked by the triad of drainpipes splayed across its south-western wall. Beyond that, ablaze in the afternoon sunlight, a grand flight of white steps with lamp posts proudly ascends an embankment. Two lines of bunting flap in the breeze, their white pennants singing out in the sunshine against the wild verdancy of a mature tree in the background. Emerging in an open space between two trees, the top of the steps is flanked on the near side by an advertising hoarding, in front of which a seated figure on a bench observes the scene below. At the edge of the picture, its glass panels glistening, is a telephone box.

Gathered together that June day are the residents 8