Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

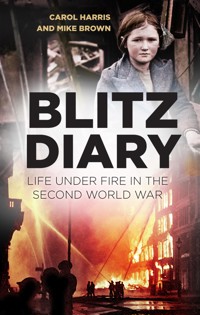

During the 1930s, war with Germany became increasingly likely. The British Government believed that it would start with massed ranks of enemy planes, dropping bombs and poison gas on civilians in major towns and cities, terrifying them into surrendering. When war broke out, preparations to protect the population were piecemeal and inadequate. As anticipated, people were shocked by the first raids and the response of rescue services was chaotic. But far from breaking morale, the Blitz galvanised public opinion in support of the war. Soon people became hardened by their experiences and attacks from the air became a normal, albeit terrible, part of daily life. Blitz Diary tells the story in a remarkable series of eyewitness accounts from the war's earliest and darkest days through to the end, when the V-2 rockets brought devastation without warning. Preservation of such first-hand accounts has become increasingly important as the Blitz fades from living memory. This expanded edition includes new chapters and new accounts from key eyewitnesses.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 272

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

BLITZ DIARY

LIFE UNDER FIRE IN WORLD WAR II

CAROL HARRIS

CONTENTS

Title Page

1. Preparing for War

2. The First Days

3. Raiders Overhead and Continuing Preparations

4. The London Blitz

5. Second Phase

6. New Strategies

7. Baedeker Raids and the Little Blitz

8. V-1s and V-2s

9. Clearing Up

Postscript

Appendix

Acknowledgements

Copyright

1

PREPARING FOR WAR

The Second World War would be a war in which civilian populations across Europe would be primary targets. As such, two factors dominated Britain’s preparation for the European war that seemed increasingly likely as the 1930s progressed: aerial warfare and the use of poison gas. Planning focused on civil defence, a term used more and more throughout that decade.

Airships and, later, aeroplanes had dropped bombs on civilian populations across the country during the First World War, killing over 1,400 people in just over 100 raids. The technology of aerial flight in particular had advanced dramatically in the twenty years since the end of that conflict. This would have an impact on military tactics as aeroplanes travelling at high speed replaced airships.

In 1924, the British government set up the Committee for Imperial Defence, which established an ARP (Air Raid Precautions) subcommittee to look at ‘the organisation for war, including Civil Defence, home defence, censorship and emergency war legislation’. This subcommittee met secretly for nine years, discussing ways of warning the population of air raids, preventing damage through such measures as restricting lighting (the blackout), gas masks, repairing damage and dealing with casualties.

In 1933, the year Hitler became Chancellor of Germany, the subcommittee set out detailed plans for ARP services to be organised through local authorities. By 1935, when the ARP Department of the Home Office was set up, these local authorities had been briefed on their responsibilities: the scheme would mean forming services to provide first aid, to deal with poison gas attacks and to rescue civilians caught in air raids. In that year, Hitler announced that Germany would re-establish her air force and introduce military conscription – both of which were in contravention of the Treaty of Versailles, which ended the First World War.

Pictured by the family Anderson shelter, these two still carry their gas masks which suggests it is early in the war. Anderson shelters consisted of curved sheets of aluminium buried several feet into the ground. Earth was shovelled on the top of the shelter – ideally deep enough to plant flowers and vegetables.

The first official broadcast on ARP services went out in January 1937 on the BBC. Debate had raged for some time as to the appropriate response to the threat of air raids. Some felt that the introduction of such a scheme was itself provocative. In the British Medical Journal, doctors argued whether they should co-operate at all. Across the country local authorities reflected this ambivalence. Some services were well organised with volunteers training to deal with the effects; most were not. In general, ARP was regarded as something of a joke.

Attitudes changed markedly in 1937, when cinemas’ newsreels showed the impact of the aerial bombardment of the Basque town of Guernica during the Spanish Civil War. Guernica was attacked on 26 April of that year by the German and Italian air forces in support of the fascist or nationalist side. Dr Duncan Leys’ letter to the British Medical Journal, written a few weeks later, sums up the feeling that Britain was woefully unprepared for the onslaught that was to come:

22nd May 1937

SIR, – It is no longer correct, I find, to think of our work as one of healing. I learn from the Home Office Instructor on Air Raid Precautions in the Birmingham area that my duties in the next war are to aid the police in ‘preventing panic,’ to ‘reassure’ the gas casualties, ‘to get it into people’s heads that whether they have gas-proofed rooms or not the important thing is for them to be under cover in their own houses,’ that ‘the whole danger of gas attacks lies in the lowering of national morale,’ and that the medical profession, as a group of persons ‘who can speak with authority,’ is to maintain that morale, in which function the Home Office considers them of only less importance than the police.

These actual quotations from a lecture are no misrepresentation of the general tenor. Having heard pacificists [sic] maintain that the main object of the Government’s air raid precautions scheme was a military one that is, to make panic or any mass protest against the continuation of war less likely, and that protection from death and injury in air raids on cities was only possible by the erection of bomb-proof shelters which the Government considered too expensive to contemplate – I attended this official lecture, delivered by a doctor to other doctors, on the invitation of the British Medical Association in order to learn what attitude was taken by the Home Office officials themselves. I was prepared to hear the lecturer say that, with the Prime Minister, he acknowledged that nothing like protection to a city population was possible short of bomb-proof and gas-proof shelters constructed for the purpose, but that until the Government had made its plans, the possibility of sudden air attack on cities existed, and that the Air Raid Precautions Department offered some advice as better than none, that a few lives might be saved by such advice, and that he was there to tell us how we could help in this limited sense. Such an approach to the question would have had my full sympathy and co-operation.

The lecturer opened by assuring us that he had no connexion with the fighting services: the Air Raid Precautions Department ‘had nothing warlike about it,’ and was intended ‘purely for the passive protection of the civil population.’ He told us that it would require anything from a few inches to several feet of concrete to protect buildings from air raids, and that ‘nobody had suggested that it was possible to protect the whole population in this way.’ He went on to describe how we might advise people to erect on scaffolding three layers of filled sandbags on their roofs, with two feet interval between the layers, to protect them from splinters from high explosives. No enemy, he continued, would use gas bombs only; high explosives would first be used to demolish important centres like railway stations, public buildings – including hospitals, which would become too dangerous to be used for other purposes than as casualty clearing stations – and generally to do as much damage to structure as possible. Thermite bombs would follow in thousands with the aim of starting a general conflagration in the city beyond the powers of the fire brigades to deal with. Gas would next be sent down by spray or bomb, and it was then that doctors and first-aid services would be needed to ‘prevent panic,’ to ‘reassure’ those affected, and to persuade people to remain in their houses.

A passing mention was made of the difficulties of protecting the aged and children and invalids, but respirators ‘were a second line of defence’ and the main thing was that people should stay indoors. No mention was made of the impossibility for most working-class families of providing a room for gas-proofing (a room rendered uninhabitable because of boarded windows and blocked ventilators or chimney), and although the lecturer said that the modern bombing plane could aim accurately to within seventy-five yards no mention was made of the certainty that windows and gas-proofing would certainly be destroyed over a wide area surrounding the fall of a high-explosive torpedo.

No opportunity was given for questions or discussion, and one is therefore unable to say how far the audience of some thirty doctors accepted the role indicated to them of persuading their neighbours that the Air Raid Precautions Scheme could really save them and their children when it must be perfectly obvious to the meanest intelligence that it can do nothing of the sort, and that the whole apparatus of the scheme is designed to deceive people into thinking that it will. I am not accusing the lecturer of deception: he was painfully honest. It is obviously much more satisfactory, from a military point of view, that people should die quietly in their homes than that they should run about the streets and possibly mob Cabinet Ministers: they might even, fearing retaliation, try to persuade our own airmen from their efforts to destroy French, German, Italian, or Russian cities.

But I should judge that the audience was almost entirely uncritical, accepting war as inevitable and their duty that outlined by the lecturer. The lecturer, by the way, inadvertently said these will be your duties, but corrected himself, and hoped we might avoid seeing the actuality.

I put it to one member of the audience after the lecture that we were being asked to perform a military duty and to help deceive people into thinking that protection was possible on the lines proposed in order that mass protest against war should be made less likely. His reply was that if an enemy attacked us in this way we might as well make it possible for our Air Force to do the same to his cities.

I should personally be sympathetic to any Government which, if it thought that the risk of war could not be avoided, sought power to tax the people to the utmost limit to provide them with protection, putting the facts in an unvarnished way before them and placing the responsibility upon them. But I hold that our people have the democratic right of deciding for themselves, now, in time of peace, whether modern warfare can justify itself, by having none of the facts hidden from them. I call the Government’s Air Raid Precautions Scheme wilful deception of the people. I believe also that it is a deception which will defeat its own object. Panic is a mild word for the wrath which the people, rudely enlightened by the first English Guernica, will display against their rulers and officials when they survey the ruins and the dead.

I am, etc.,

DUNCAN LEYS, M.D.Oxon.

The British government passed the ARP Act, which came into effect on 1 January 1938. This actually compelled local authorities to set up ARP schemes and offered substantial funding towards the costs of doing so. Schemes had to include wardens, first aid, gas decontamination, casualty clearing stations and repair and demolition services. The Auxiliary Fire Service, representing a major expansion of the established fire brigades, was also introduced.

In September 1938 Germany threatened Czechoslovakia and it seemed that war was imminent. The Munich Agreement, Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s attempt to bring ‘peace in our time’, was welcomed by cheering crowds for Britain. Hitler assured Chamberlain and the rest of Europe that he had no further territorial demands. In return, Britain and France ignored the Czech government’s views and agreed to Germany incorporating into its own borders the Czech Sudetenland. But a massive increase in volunteers for the various civil defence schemes, in the year between Munich and the outbreak of war in September 1939, suggests that few believed this to be anything more than a delay in which to prepare as fast as they could for the onslaught.

Shelters were dug in public parks, people filled sandbags and buckets of water, and Anderson shelters were distributed to civilian homes. Public meetings, volunteer recruitment drives and training schemes for civil defence personnel and the general public gathered pace. Expectations were that the air raids would start soon after war was declared and would result in planes dropping poison gas on the major cities of Britain. Official estimates, based on the effects of bombing in Spain, were that 120,000 people would die in the first week of the war, and about twice that number would be injured. This estimated total of 360,000 casualties in one week was in fact more than twice the number of people killed and injured in Britain in this way during the whole of the war.

Ann Maxtone Graham was the American wife of a British serviceman living in Earl’s Court, London. This is her memoir, written initially to give her family in America an idea of the war in Britain:

Little by little, we started to check what we should do if war came, for we began to believe it might. In March of 1938, Pat enlisted in the 151st battery anti-aircraft brigade and I bought six gallons of gasoline which I stored in a funny little summer house in the back garden. At one time it housed the boys’ rabbits. I bought a can of ether in case I had to put the dogs and cats to sleep.

Trenches were dug in Kensington Gardens and Hyde Park and sand bags made protective walls round doorways. Our war didn’t burst upon us like Pearl Harbor. It came in sneaky little ways. Suddenly there was a flier in the mail box: ‘Notice to inhabitants – Air Raid Precautions.’ Gas masks would be issued, they said ‘should it become necessary.’

Pat was away in camp for two week’s training and came home on September 26th but was called up the next day, and off he went to his guns and rockets.

Ann volunteered to deliver gas masks to people who could not leave their homes: ‘I went flying around, had an hour’s training in how to fit the horrid things and then set off on my delivery route.’ While she was out on her rounds:

There was a group of people huddled around a wireless and they beckoned me to join them. Mr Chamberlain had just arrived home from Berlin and a conference with Hitler. He was shouting ‘Peace in our time! Peace in our time! All is well.’

We all collapsed like pricked balloons. After all, he was the Prime Minister, and we thought he knew what he was talking about. I crept home, had my hot bath, but a stiff drink instead of my cup of tea. It had been quite a day. Pat came home from his gun site and went back to his job. There were certain evenings and weekends given to training. Life went on as usual but there were stirrings, and we felt that maybe someone was doing a little pushing and trying to get ready in case war really came.

It occurred to me that if other people were doing a little pushing, maybe I should do a little quiet pushing too. So I went up to the Town Hall of Kensington, and after a little struggle, I got in to see the man who was in charge of the First Aid Posts.

As a result, she set up a depot at her home making surgical dressings:

I don’t know how many hundreds of thousands of dressings and bandages we made for Kensington, but when they were done they were all dispatched to the Town Hall. To our fury, they were never acknowledged nor did we receive one word of thanks. I know they were used, for some of our friends saw them in the First Aid Posts and recognised my writing on the labels.

So much for Kensington! We supplied Hackney with the things and they were gratefully acknowledged.

We rented a house in the New Forest for a month at Christmas time (1938). It was right on the Solent opposite the Isle of Wight and all the big ocean liners went past on their way to Southampton. Although we didn’t know it, this was our last peaceful Christmas for some very long years, and the last one that I would have with our children. Perhaps there was something that gave us a warning, as we made the most of it, kept the house full of guests, and didn’t go back until the 21st January. British children get a month’s holiday at Christmas.

My darling Dad died on 23rd March, and I longed to go home to Mother. She had a very nice niece staying with her and she begged me not to come. So I kept on with my surgical dressings and other odd jobs which came my way. A letter from my mother in May asked, ‘Aren’t you worried about the war? You never mention it, except for the surgical dressings.’

So I broke down and told her about the cans of gasoline stored in the summer house and the ether to put my dogs and cats to sleep if the need arose. No sooner had the letter reached Mother than I had a cable from her to say that she was coming to England at once. And so she did. I don’t think she liked the trenches in the park or all the sandbags any better than we did. Nor did she like Pat going off to camp and leaving me all alone in London. She was so distressed about all this that at last I said the boys and I would go back to America with her for a visit. We sailed on July 22nd on the Georgic.

That is how I came to be in America when the war started. If I hadn’t been there, I would never have sent the boys [Peter aged 12 and twins John and Michael aged 10] to America, as many of my friends and relatives did. But as I was there with them, I had to make a decision as to what I should do. I left them and, sometimes, I wish with all my heart that I had not.

Henry Beckingham, aged 19, had volunteered for military service in May 1939. He had just left technical college and started his first job as a draughtsman with a firm of consulting engineers:

The decision was whether I should go for the TA [Territorial Army], spending weekends in the drill hall plus a 14-day camp annually, or alternatively to wait until the age of 20 years and spend 12 months away with the militia.

I decided that the Territorial Army offered me the best option, as this would not seriously affect my civilian career. How wrong that decision was would be made very clear in the months ahead.

In addition to the call for volunteers to work in military and civilian services, a limited form of conscription was introduced in spring 1939. Under the Military Training Act, single men aged 20–22 were liable to be ‘called up’ for military training. They were to be known as ‘militiamen’ as they were not part of the regular army. At the outbreak of war the National Service (Armed Forces) Act extended conscription: men between the ages of 18 and 41 could now be compelled to serve in the armed forces.

R.H. Lloyd-Jones was another volunteer. He was a 29-year-old solicitor in Ealing when he joined the Territorial Army in 1938. He served first with the 424 AA (Anti-Aircraft) Company, 36 Searchlight Regiment, RE (Royal Engineers) and here recalls his experience of the first batch of conscripts:

Spring and Summer 1939

War was becoming very near and the Government had decided that the Anti-Aircraft defence would have to be permanently manned.

Conscription had come into force and some of the first intake, the militia-men, as they were called, were being trained for AA work, but until they were ready, the existing AA units like our own would have to man the sites, four weeks at a time. This process, quaintly named ‘couverture’, would start in the middle of June. Our regiment was one of those which were given the second period of four weeks, from 16th July to 14th August 1939 … At about the same time we were told where our war sites would be. They were dotted over the country every few miles between Bedford and St Neots.

Some of us who had seen the posters ‘Join the Anti-Aircraft and defend your homes’ had not expected to be so far from our homes. It was explained to us that we would be in the outermost ring of the defences of London.

By now we were being sorted out according to the duties we would be carrying out on site.

Perhaps at this point I should mention that a Searchlight Detachment consisted of ten men who were numbered 1 to 10, these numbers signifying what they had been trained for, no 1 being the Detachment Commander. Nos 2 and 3 were spotters who watched for aircraft with binoculars, or more often with the naked eye because there were not enough binoculars to go round.

No 4 was the Projector Controller who stood or walked at the end of a bracket called the ‘long arm’ attached to the projector, with a kind of steering wheel to obtain (it was hoped) the right elevation of the beam. No 5 was an electrician, the searchlight operator, responsible for the arc lamp which produced the light. No 6 was in charge of the sound locator and was the Second in Command of the detachment. A one-way telephone enabled him to give directional orders to no 4 who wore a head set for this purpose. Nos 7 and 8 were the listeners who operated the Sound Locator, one of them listening in bearing and the other in elevation. No 9 was in charge of the lorry or diesel generator and No 10 was the spare man, which in actual fact meant that he was the cook.

Our training for these duties was partly individual, the spotters for instance being instructed in classes for aircraft recognition etc., and partly in Detachments comprising numbers 1 to 8 when we carried out imaginary engagements of ‘targets’ (as the aircraft was always known to us) with standard drill known as a ‘manning drill’ which always seemed to follow the same pattern, starting with ‘target heard’ and so to ‘target seen’ after which there was a crescendo of imaginary activities which always culminated in ‘station attacked by low-flying aircraft – machine gun action’ followed by the alarming order ‘GAS’ but eventually subsiding to ‘target inaudible’ and ‘dowse’.

During the couverture we would be subject to Army discipline and apparently this made it necessary that the Army Act should be read to us. This was done on a parade outside the barracks one evening.

Captain Ingram did the actual reading and although he started in daylight, it went on so long, with section after section being read out, each one ending with the appropriate penalty which in nearly every case seemed to be death, that after a time the daylight failed and a sergeant had to stand by him with an electric torch.

There must have been four hundred men on parade. All of them had made sacrifices to join the Territorial Army and some of them would lose their lives in the impending war. These men stood there, motionless in the darkness while the voice droned on and on, threatening them with the death penalty. This made a very encouraging impression on me. While such things can happen, I said to myself, England will never lose a war.

Barrage balloons were dangerous and unwieldy, being on average 8.9 metres long and 7.6 metres in diameter. They were filled partially with hydrogen, partially with air, and were winched up usually from lorries and held in place by cables. Barrage balloons were essential defences against air attack as they forced all aircraft to fly higher around key areas such as industries, ports, towns and cities. This made bombers less accurate and forced them up into the range of anti-aircraft guns.

2

THE FIRST DAYS

Most of those old enough to remember the declaration of war on Sunday 3 September 1939 heard Neville Chamberlain’s broadcast on BBC radio at 11 o’clock in the morning and remember the events that followed. The crisis was precipitated when Germany invaded Poland, and at a tense and angry sitting of the House of Commons on the Saturday evening, many MPs had voiced their objections to further appeasement. As his broadcast made clear, Chamberlain himself hoped war could be averted as it had been a year before.

I am speaking to you from the Cabinet Room at 10 Downing Street.

This morning the British Ambassador in Berlin handed the German Government a final note stating that, unless we hear from them by 11 o’clock that they were prepared at once to withdraw their troops from Poland, a state of war would exist between us. I have to tell you now that no such undertaking has been received, and that consequently this country is at war with Germany.

You can imagine what a bitter blow it is to me that all my long struggle to win peace has failed. Yet I cannot believe that there is anything more or anything different that I could have done and that would have been more successful.

Up to the very last it would have been quite possible to have arranged a peaceful and honourable settlement between Germany and Poland, but Hitler would not have it. He had evidently made up his mind to attack Poland, whatever happened, and although he now says he put forward reasonable proposals which were rejected by the Poles, that is not a true statement.

The proposals were never shown to the Poles, nor to us, and though they were announced in a German broadcast on Thursday night, Hitler did not wait to hear comments on them but ordered his troops to cross the Polish frontier the next morning.

His action shows convincingly that there is no chance of expecting that this man will ever give up his practice of using force to gain his will. He can only be stopped by force.

We and France are today, in fulfilment of our obligations, going to the aid of Poland, who is so bravely resisting this wicked and unprovoked attack upon her people. We have a clear conscience – we have done all that any country could do to establish peace.

The situation in which no word given by Germany’s ruler could be trusted, and no people or country could feel itself safe, has become intolerable. And now that we have resolved to finish it I know that you will play your part with calmness and courage.

At such a moment as this the assurances of support which we have received from the Empire are a source of profound encouragement to us.

When I have finished speaking, certain detailed announcements will be made on behalf of the government. Give these your closest attention. The government have made plans under which it will be possible to carry on work of the nation in the days of stress and strain that may be ahead …

Now may God bless you all. May He defend the right. For it is evil things that we shall be fighting against – brute force, bad faith, injustice, oppression and persecution – and against them I am certain that right will prevail.

For R.H. Lloyd-Jones, the outbreak of war seemed inevitable from the moment he heard the news of Germany’s invasion of Poland:

On the morning of Friday, 1st September, we were taken in as usual to Section HQ at Wilden for concentration. During the morning’s training on searchlight duties I noticed at one point that all the sound locators, instead of being pointed up in the air as they should have been, were in a horizontal position and directed towards one of the huts on the site. There was a news bulletin being read on the radio, and our listeners were receiving, in this unauthorised way, the first news that Germany had invaded Poland, meaning in effect that war was now inevitable.

As we left Wilden, to be driven back to our sites, cheerful shouts were exchanged between the occupants of the lorries, mostly to the effect that we would all see each other in Poland. One such shouted greeting has for some reason stuck in my memory; it was ‘See you in Upper Silesia’. I don’t think anyone nowadays would know or care where Upper Silesia was or is, but at that time it was a locality which was very much in the news.

On Sunday morning, 3rd September, arrangements had been made for a civilian hairdresser to visit the sites. Sitting on a spotter’s chair in the middle of the field while having my hair cut I heard a radio set which someone had turned on, from which could be heard the very pleasant voice of Neville Chamberlain giving the not very pleasant news that we were now at war with Germany.

Parents and children reacted quite differently, as Leslie Gardiner aged 12 remembered:

Those words had hardly left Mr Chamberlain’s lips when the sirens sounded and we expected German planes to appear immediately. My father ushered my mother, my brother, me, and the dog down the garden to the Anderson shelter at the bottom of the garden.

As we hurried down the garden I looked over the fence to see our neighbour shepherding her two small children and carrying her small baby towards their shelter. What my brother and I found amusing was the fact that the two small children and their mother were wearing their gas masks and the baby was enveloped in a baby gas mask (a sort of large rubber envelope with a pump which had to be continuously pumped in order to keep the baby supplied with filtered air). Not so amusing for the harassed mother, but funny enough for a twelve, and a twenty-one year old.

After a short time without any sign of the Luftwaffe, my brother decided to shovel some more earth on to the shelter which had been left, after its installation, with the light covering of soil which the workmen had given it. I offered to help big brother and we set to with a couple of garden spades. Apparently, inside the shelter, the sound of the stones rolling down the sides of the shelter sounded like gunfire and our mother urged us to re-enter the shelter at once. We did not do so, but redoubled our efforts with the spades so as to create the impression of a huge barrage. Our father then emerged from the shelter and upon discovering that we were teasing our mother threatened us with dire consequences if we did not desist. At that moment the all clear sounded and we had survived our first few hours of war.

The expectation of immediate air attacks also created tension in the RAF, as fighter pilot Alan Deere recalled:

On the first Sunday of the war, a lone aircraft returning from patrol was plotted as hostile and a squadron scrambled to investigate. This squadron became split and sections from it were in turn plotted as hostile, and more aircraft sent to investigate until eventually the operations room tables, on which were plotted the raids, were cluttered with suspect plots. For about an hour, chaos reigned, and in this time nearly all the squadrons based to the east of London had been scrambled. I had trouble starting my aircraft and was late getting off and in the hour I was airborne spent the whole time trying to join up with my squadron which was receiving so many vectors [course instructions] that it was impossible to follow them. When I did eventually join up, the squadron was near Chatham where the anti-aircraft guns heralded our presence by some lusty salvoes, at which we hastily altered course despite the controller still insisting that we investigate the area. Not all the incidents … were amusing. 74 Squadron, led by ‘Sailor’ Malan, had also been sent off and their rear section of three encountered a pair of Hurricanes from nearby North Weald which, in mistake for the enemy and in the excitement of this glorious muddle, they attacked and shot down, killing one of the pilots.

This truly amazing shambles – known to those pilots as the ‘Battle of Barking Creek’ – was just what was needed to iron out many snags in our control and reporting system and to convince those who were responsible that a great deal of controllers, plotters and radar operators, all of whom had been hastily drafted in on their first emergency call-up, was still required.

Betty Bullard, aged 21, had volunteered for the ATS (Auxiliary Territorial Service), and was working in a recruitment office in Norwich. She recorded the day war broke out in her diary:

Sunday 3rd September 1939