8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

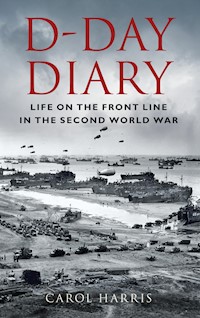

6 June 1944 is one of the most memorable dates of the Second World War. It marked the beginning of the end of the conflict as Allied forces invaded Normandy and fought their way into Nazi-occupied Europe. Operation Overlord, as the invasion was codenamed, was an incredible feat. It also proved to be a turning point that would eventually result in the defeat of Nazi Germany. Around 150,000 soldiers landed on the beaches of Normandy on the first day in the largest amphibious operation in history. Within a month more than 1 million men had been put ashore. As memory becomes history, first-hand accounts of this incredible moment become more and more precious. In D-Day Diary, historian Carol Harris brings together remarkable tales of bravery, survival and sacrifice from what was one of the war's most dramatic and pivotal episodes.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

Acknowledgements

The Allied landings in Normandy on D-Day, 6 June 1944 marked the beginning of the end of the Second World War. This short book tells the story of the event through the accounts of eyewitnesses.

Today, the D-Day invasion is viewed as not only the biggest but also the most successful invasion ever launched. These contemporary accounts show that at the time, such an outcome seemed far from certain.

As far as I have been able to ascertain, all of those whose accounts make up this book survived the war, although few, sadly, are alive today.

I would like to thank the following people who gave me permission to quote from their own or their relatives’ accounts: Sheila Austin, Barbara Beal, the family of Maureen Bolster, W. Cutler, Annette Conway (for extracts from the papers of Rev. Leslie Skinner), A.M. Kerr (for the account by Captain Maurice Jupp), and Patricia Wildman. Also, to Olivia Beattie at Biteback Publishing, and to the following for permission to quote from online sources: Patrick Elie of the 6Juin website, Mark Hickman of the Pegasus Archive, Lew Johnston from the Air Mobility Command Museum, H. Kalliomaki at Veterans Affairs Canada, the Black Hills Veterans Writing Group, Andrew Whitmarsh of the D-Day Museum in Portsmouth, and Paul Zigo and Donna Bastedo of Center for World War II Studies and Conflict Resolution.

I am especially grateful to the following, without whom this book could not have been written: William and Ralph for their administrative support; Mike Brown for his expert advice; Sophie Bradshaw and Lindsey Smith of The History Press for keeping the project on track, and staff at the Imperial War Museum Research Room, especially Simon Offord, Documents and Sound Archivist.

Contents

Title

Acknowledgements

Abbreviations

1 Testing and Training

2 Deception and Delay

3 Airborne Assault

4 Across the Channel

5 On the Beaches: Sword and Juno

6 On the Beaches: Gold, Omaha and Utah

7 Moving Inland

8 Casualties and Non-combatants

Sources and Further Reading

Glossary

Copyright

Abbreviations

AA

Anti-aircraft

ack-ack

Anti-aircraft guns ( )

ADS

Advanced Dressing Station

APM

Assistant Provost Marshal

ARK

Armoured Ramp Carrier

ARV

Armoured Reconnaissance Vehicle

ASR

Air Sea Rescue

AVRE

Armoured Vehicle, Royal Engineers

BM

Beachmaster

Brig. Gen.

Brigadier General

Capt.

Captain

CIGS

Chief of the Imperial General Staff

CO

Commanding Officer

Col

Colonel

DD tanks

Duplex Drive tanks

DUKW

Six-wheeled amphibious vehicle

DZ

Drop Zone

EME

Electrical and Mechanical Engineers

ENSA

Entertainments National Service Association

FANY

First Aid Nursing Yeomanry

Fd Sqn

Field Squadron

FM

Field Marshal

FUSAG

First United States Army Group

FW

Focke-Wulf

Gen.

General

Grp Capt.

Group Captain

GT

General Transport

HAA

Heavy Anti-Aircraft

HE

High Explosive

IC

In charge (of)

IO

Intelligence Officer

LAA

Light Anti-Aircraft

LCA

Landing Craft, Assault

LCI (L)

Landing Craft, Infantry (Large)

LCM

Landing Craft, Mechanised

LCP

Landing Craft, Personnel

L/Cpl

Lance Corporal

LCR

Landing Craft Rocket

LCT

Landing Craft, Tank

LCT(R)

Landing Craft, Tank (Rocket)

LCVP

Landing Craft Vehicle, Personnel

L/Sgt

Lance Sergeant

L/Sgt

Lance Sergeant

LST

Landing Ship Tank

Lt Col

Lieutenant Colonel

Lt

Lieutenant

Maj. Gen.

Major General

Maj.

Major

m/c

Motorcycle

Me

Messerscmitt

MG

Machine Gun

MI5

British intelligence agency

ML

Motor Launch

MO

Medical Officer

NAAFI

Navy, Army and Air Force Institutes

NCO

Non-Commissioned Officer

OC

Officer Commanding

PIAT

Projector, Infantry, Anti-Tank

PO

Pilot Officer

RAF

Royal Air Force

RA

Royal Artillery

RASC

Royal Army Service Corps

REME

Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers

RE

Royal Engineers

Rev

Reverend

RM

Royal Marines

RN

Royal Navy

RNVR

Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve

R/T

Radio Telegraph

RV

Rendezvous

SBG

Small Box Girder

Sgt

Sergeant

SHAEF

Supreme Headquarters Allied

Expeditionary Force

Spr

Sapper

SP

Self-propelled

Sqn Ldr

Squadron Leader

TCG

Troop Carrier Group

TCS

Troop Carrier Squadron

Tp

Troop

TSM

Temporary Sergeant Major

Wg Cdr

Wing Commander

W/Ops

Wireless Operators

WRNS

Women’s Royal Naval Service

W/T

Secret messages transmitted by Morse Code

1

Testing and Training

The early years of the Second World War were marked by the rapid advance of Germany and Japan as they swept through Europe and the Pacific regions. By the end of 1940, most of Western Europe was under Nazi rule and Britain stood alone. Japan, Germany and Italy had signed the Tripartite Pact, establishing them as the Axis Powers and guaranteeing mutual support if any one of them were to be attacked by any country other than the Soviet Union.

It became increasingly obvious, as the years passed, that an invasion of mainland Europe by the Allies would be necessary to secure victory and end the war. American involvement was essential: without their resources – equipment and soldiers – Britain could only hope to stay in less-than-splendid isolation, cut off from Europe. There, its closest neighbours – France, the Netherlands and Belgium – were under Nazi control, and others such as Switzerland, Portugal and Spain remained neutral.

The Japanese attack on the US base in Pearl Harbor in December 1941 changed the picture dramatically, forcing the United States, in which anti-war sentiment had been a strong influence, to enter the war. This meant that, suddenly, the Allies had enough manpower and equipment to make an invasion possible, although nothing on the scale required had ever been attempted before.

Allied plans for an invasion of Northern France were first outlined in Operation Roundup in 1942. The plan was drawn up by President Eisenhower, then Brigadier General of the US forces, and the invasion was to take place in early 1943. It quickly became apparent, however, that this was unlikely to happen: among British objections were those of Winston Churchill, who favoured an invasion through the Mediterranean, and those of British military chiefs, who wanted to wait until the German Army was worn down by fighting in the Soviet Union.

Samuel Eliot Morison, an American historian and sailor in the US Navy, wrote in his book The Invasion of France and Germany that, given shortages of merchant shipping, landing craft and other resources, the planned date of early 1943 was unrealistic. Any such invasion called for a force of between 500,000 and 750,000 soldiers and 5,800 aircraft. British and Allied forces from the rest of Europe would have to await the arrival of US forces and equipment, which would have to be sent by sea and air across the Atlantic.

Operation Bolero, the codename for this build-up of military personnel and equipment, began at the end of April 1942. Over the next two years, soldiers, sailors and airmen drawn from Britain, America, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the Netherlands, France, Belgium, Norway, Poland and Czechoslovakia were trained and organised into the largest invasion force ever seen.

Naturally, the build-up of such enormous forces required an extraordinary level of secrecy.

If the German Army discovered the true date and location of the invasion of Europe, it could plan a response and inflict heavy casualties on the invading forces.

Landing craft waiting to leave England. (Author)

There was ample evidence of the catastrophe which could follow a botched invasion. In August 1942, an Allied raid was attempted on the French port of Dieppe. The invading force totalled more than 6,000 troops, included 5,000 Canadians, 1,000 British Commandos and fifty American Rangers. They were supported by eight Allied destroyers and seventy-four Allied air squadrons. The aims were to gather information and destroy equipment and installations.

The Allies knew little about their target. The town and beaches were heavily defended by 1,500 German infantry with machine guns and artillery. Over 60 per cent of those – mainly Canadian – forces who went ashore were killed, wounded or taken prisoner. The only success of the nine-hour raid was the capture, by commandos under Lord Lovat, of a gun battery. Losses among the RAF and Navy were high too.

Kenneth Beal, a signalman with the Light Coastal Forces of the Royal Navy, was on the raid in Motor Launch 194. He wrote later:

The old timers on board, who knew the drill for these occasions, found time to give themselves a thorough wash all over. Then they changed their underwear and replaced it with the clean items. Why? Because, they said, many wounds were made worse by fragments of dirty clothing carried into them. I sobered up a bit at this point. Most of us copied them.

Before dawn, we saw tracer fire up ahead between our leading ships and a German coastal convoy. It lasted about 15 minutes and I wondered what the enemy’s look-outs ashore would make of it. A little later came the sound of our aircraft passing overhead as the early grey light began to lift the darkness.

We had, by this time, passed safely through the Germans’ minefields. Our sweepers up ahead had cleared a path for us, dropping small lighted buoys to mark the swept channel. Red to port and green to starboard.

The sound of bombing ahead commenced, and gradually crescendoed. The sky lightened and we could see smoke from the land, and debris being hurled high into the air. The exchange of fire between the Van [vanguard] of our forces and the shore began slowly. It grew in intensity until, in what was now bright light, we ourselves, accompanied by the orchestra of battle came into the fight …

My fear was made worse by the unbearably slow approach to the beach and the guns. This creeping approach was very hard on my nerves. I found that something was pulling me strongly in the other direction, and if I had been a soldier on land, I would have run for it. At this point we did turn for the open sea, but only to go back and get one of the LCP’s and give her a tow.

The crew of ML 214 who were leading the group told me after, that when they saw us turn tail and speed out to sea again, they felt very bad. Actually it made me feel better. It was only a temporary retreat and we had to cross that nasty stretch of water a second time before we rejoined the group.

The shells were now exploding right in amongst our LCPs. ‘Poor Devils’ I thought when one was almost capsized by one of the huge shells. It righted itself however and carried on in. Then clearly across the water from the Canadians came the boost to my morale that I so badly needed.

BAGPIPES. In peacetime I disliked them. On that morning they were music indeed. The Camerons of Canada’s piper was playing his wild music to take his regiment in to the beach to face the enemy.

ML 214 had originally headed in slightly to the west of where she should have been. Discovering her error in time she altered course slightly to the east, approaching the correct beach diagonally. Not very good navigating at about 6.00am on a bright and sunny morning.

At about this time the big guns that had been harassing us ceased their firing.

We thought that we had by then got in so close that the guns, high on the cliffs, could not depress down on to us. I read later that our commandos had gone in ahead of the Camerons, scaled the cliffs up to the gun emplacements, and after a short but desperate fight had silenced the guns and their crews. This was one of the few successes of the day. Good old Lord Lovat and his bonny men.

Over on the other side of the assault area the Free French Chasseurs, smallish craft though bigger than MLs, were carrying the Marines. This I heard from Sparks during the morning, together with the fact that the Marines did not get ashore. If that is so, I do not know the reason why.

We had no idea how the battle in general was going. Jerry had apparently only recently reinforced his defences with extra troops, and was ready and waiting for the Canadians to come to him. The Canadians stood little chance.

During the morning the Germans, clever as ever, started using the Canadian radio frequencies and call signs that our lot were using, which they must have gained knowledge of through their monitoring.

They issued confusing orders and contradictory instructions, probably using renegade Frenchmen, and this did not help our lot one bit.

Sapper Vic Sparrow of the Royal Canadian Engineers was one of the Canadian troops who took part in the assault:

I hit the beach and everything was just going like crazy. I just curled up and I don’t think I moved a muscle for a while. I would peek out and all of a sudden I would see a guy a little piece away from me and he’d look up and the next thing he was gone. He got it. It was that way. Finally things did quieten down a bit. I got up and walked along the beach a piece and I covered up this one chap and covered up a couple of lads. A fella by the name of Billy Lynch, who was in my outfit, he started to write a book. I got a copy of the transcript and in it he said he looked up, he was down by this timber, and he looked up and saw Lieutenant Shackelton and Sapper Sparrow running up and down the beach. He said the crazy so and so’s, they’re going to get killed. Well I didn’t get killed. I didn’t get a scratch as far as that was concerned. But, I saw one chap when he tried to go over the wire, he got hit and he was just burned to a crisp right there. It was almost impossible to move without getting hit.

Private John Patrick Grogan, from the Central Ontario Regiment, was also pinned down by heavy German fire.

We knew what we were supposed to do all right. We were to get to land and get over the beach as quickly as we could and get up over the sea wall. But on landing, I guess the first thing I recall is that some of the people who had landed before me . . . there was the beach lined with people all lying there. And the stones. There were big stones, huge stones on that beach. And it seemed to me to be crazy for these people to be lying down there. We had a habit in manoeuvres, you’d run so far then you’d duck down or you might crawl a bit. But I just couldn’t understand what they were all lying there for. But they were dead. They were either dead or they had all been hit. I got up near the sea wall and near the sea wall you were fairly safe. But out from the sea wall six or seven feet there was no one living. So these people that were down by the water’s edge when I went off had all been hit. And the ones that I had waved good-bye to that morning, and the ones we had joked with such as Sammy Adams, he was one of the first that I saw, Joe Coffey, Huey Clements, Ernie Good, all of these people all dead in such a short space of time …

Then I heard a loud speaker. The fellow talking English with an accent, a German accent. But he spoke perfect English. He said that we didn’t have a chance, ‘to throw down your arms’. He called us brave Canadians and he said, ‘throw down your arms and surrender’, and that the wounded would be taken care of, or else we would be annihilated. Then I heard someone say, going running by, the word ‘surrender’, you see. I ventured out from where I was and could see down a piece a group of people with white bandages and an odd white towel and with their hands up. Things began to get quiet. Just as if there was a great stillness. After all of this noise, everything stopped for a bit.

Someone else, took a look out and they said that the beach was swarming with German soldiers.

On his motor launch, Kenneth Beal watched events unfold:

We went alongside a Tank Landing Craft, which was slowly sinking …The Canadian major on board had seen three Canadian tanks go up the beach and get knocked out in seconds. The enemy fire had been sweeping the beach so intensely that he would not send his infantry to follow them to certain death. Good guy that officer.

Before that TLC backed off she was hit a number of times. Her bridge took four direct hits. All the upper deck Navy crew were either killed or critically wound. Except for the skipper. He, poor man, was only just in control, shaking like a leaf. But he hadn’t got a scratch on him. We took off all the injured. All were stretchered. Their sick bay Tiffy [sick berth attendant] told our lads that some were dying.

The Canadians were now manning the TLC’s guns.

We pulled away from her to take the wounded to a destroyer, which had sick bay facilities. After we had passed over those casualties, we pushed off again on our rather aimless patrol. I was glad because I instinctively thought it a bad idea to form even small clusters of ships. They made a better target for the Luftwaffe.

On shore there was any amount of noise going on. We moved slowly about on a flat calm sea. I saw our Boston Bombers coming in from England. Skimming in low over the waves to hit their targets ashore …

Soon after midday we took in tow a small landing craft, drifting without power, with one petty officer on board, and towed him all the way back to Newhaven. Some time after 2.30pm, our people decided that enough was enough and preparations were made to leave. Many Canadians were left on shore to be captured. The force brought back some prisoners.

The raid was a failure, but it taught us the folly of trying to land directly at a port, and on its nearby beaches.

Our boat was the last of the flotilla to enter Newhaven, at 11:30pm. Our Base staff, worried stiff, were there to greet us. They told us that they had spent part of the day on the breakwater listening to the distant thunder coming from Dieppe, sixty miles away. Our late arrival back brought them on board to welcome us. It was touching to suddenly realise that we meant something to them.

A few days later, on the train going into Brighton, I noticed some Canadians in the same carriage as me. They were looking tired and dishevelled, and fed up.

One of them was wearing a Canadian shoulder flash and I tried to open conversation with him. Well, as we had been on the other side together, up to a point, I thought that I could say Hallo at least. He however was very tight lipped, so I dropped the attempt. That incident has always worried me a little. Was his reluctance to talk because he had lost a friend and hadn’t recovered from the shock? Had they been told ‘No talking’? Or, and this is a slightly guilty feeling on my part, had ML 214, going into the beach in the first instance in the wrong place, given the Canadians trouble we hadn’t heard about? I only hope that it was not the latter.

The next day, on the train to Newhaven I shared a carriage with some civilian workmen on their way to work. They were talking loudly and knowing about the raid, and a lot of drivel it was. One chap said that he had seen our cruisers exploding, and I tore into them verbally. I was still feeling raw under the surface about the mess it had been, I only know that the wild inaccuracies they were putting forward as facts, made me very angry, and I overreacted.

Dieppe was studied carefully in the planning of the invasion, and by 1944, techniques, equipment and tactics had changed. Some Allied military leaders, including Vice-Admiral Louis Mountbatten, the British Chief of Combined Operations, who planned the raid, said that it had given valuable lessons. Others, such as General Sir Leslie Hollis, who was Secretary to the Chiefs of Staff Committee and deputy head of the military wing of the War Cabinet, thought it an unmitigated disaster and that its lessons would have been learned in other, less costly ways.