Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

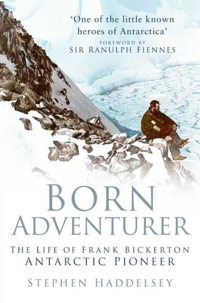

Soldiers and sailors, geographers and geologists, submariners and balloonists all flocked to Antarctica during the 'Heroic Age' of Polar exploration. No one better represented this eclectic band than Frank Bickerton, engineer on Douglas Mawson's Australasian Antarctic Expedition (AAE) of 1911–14. A true pioneer of Antarctic exploration, he piloted the expedition's 'air-tractor', established the first crucial wireless link between Antarctica and the rest of the world, and discovered one of the first meteorites ever to be found on the continent. Treasure-hunter, explorer, fighter pilot, entrepreneur, big-game hunter and movie-maker, Bickerton not only made a major contribution to the success of the AAE, but was also recruited by Ernest Shackleton for his ill-fated Endurance Expedition, dug for pirate gold on Robert Louis Stevenson's Treasure Island, survived bloody dogfights over the Western Front during the First World War, and flirted with the glittering world of 1920s Hollywood. In Born Adventurer, historian Stephen Haddelsey draws on unique access to family papers, journals and letters to provide a thrilling account of Bickerton's rich and colourful life.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 485

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2005

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

About the Author

Stephen Haddelsey is the author of many books on Antarctic exploration history, including Ice Captain, Shackleton’s Dream and Icy Graves, as well as other topics. He lives in Nottinghamshire.

Praise for Born Adventurer

‘Some larger-than-life characters enter legend; others enter literature – the model for at least three fictional explorers, Frank Bickerton stuffed his life with event, and not only took part in the Australasian Antarctic Expedition of 1911–14, but was a treasure-hunter, served in both world wars … and worked in the British film industry in its heyday … What’s here represents enough for several ordinary lives.’

Geographical Magazine

‘The story and the way it’s told are brilliant.’

Cross & Cockade Journal

‘The author has done a fine job of piecing together Bickerton’s story and providing an insight into this engaging character … the sort of man without whom the expeditions could not have succeeded.’

For my wife, Caroline,

without whose unflagging support and encouragement

this project would have remained permanently ice-bound.

There are men it would be utter ruin to place in positions of staid and tranquil respectability, and yet who make good names. They are born to be adventurers.

Charles Lever, The Diary and Notes of Horace Templeton

Front cover image: Taken during the Australasian Antarctic Expedition by Frank Hurley. (State Library of New South Wales)

First published 2005

This paperback edition first published 2023

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Stephen Haddelsey, 2005, 2023

The right of Stephen Haddelsey to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 75249 564 4

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

List of Illustrations & Maps

Foreword by Sir Ranulph Fiennes Bt, OBE

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Author’s Note

One

Of Ice and Treasure

Two

Tempest-Tossed

Three

Terre Adélie

Four

This Breezy Hole

Five

Westward Ho!

Six

Hope Deferred

Seven

Endurance

Eight

Air War

Nine

The Restless Heart

Ten

From Cape to Cairo

Eleven

Movies and Marriage

Notes

Sources and Bibliography

List of Illustrations & Maps

ILLUSTRATIONS

1. Joseph Jones Bickerton. (Courtesy of Mrs Karen Bussell and Mrs Penny Stansfield)

2. Eliza Frances Bickerton (née Fox). (Courtesy of Mrs Karen Bussell and Mrs Penny Stansfield)

3. Francis Howard Bickerton, at 4 years old. (Courtesy of Miss Rosanna Bickerton)

4. Cocos Island, 1911. (Courtesy of Mr Angus MacIndoe and Mrs Sophia Crawford)

5. The Vickers REP D-type monoplane at Adelaide, October 1911. (Courtesy of Miss Rosanna Bickerton)

6. Frank Bickerton on the AAE, 1912, photographed by Frank Hurley. (Courtesy of the Mawson Antarctic Collection, South Australian Museum, Adelaide)

7. Bickerton in the air-tractor at Cape Denison. (Courtesy of the Mawson Antarctic Collection, South Australian Museum, Adelaide)

8. Bickerton working on the air-tractor in the hangar. (Courtesy of the Mawson Antarctic Collection, South Australian Museum, Adelaide)

9. The blizzard, by Frank Hurley. (Courtesy of the Mawson Antarctic Collection, South Australian Museum, Adelaide)

10. Bickerton in the trenches, c. 1916. (Courtesy of Miss Rosanna Bickerton)

11. Bickerton with a Sopwith Pup, 1918. (Courtesy of Lady Angela Nall)

12. Bickerton recuperating from wounds, May 1918. (Courtesy of Mrs Karen Bussell and Mrs Penny Stansfield)

13. ‘The Explorer’: Bickerton painted by Cuthbert Orde, Paris, 1922. (Courtesy of Mr Angus MacIndoe and Mrs Sophia Crawford)

14. Bickerton at Black Duck, Newfoundland, 1927. (Courtesy of Mr Angus MacIndoe and Mrs Sophia Crawford)

15. En route to Karonga, Nyasaland, 1932. (Courtesy of Miss Rosanna Bickerton)

16. The cast and crew of The Mutiny of the Elsinore, Welwyn Studios, 1937. (Courtesy of Mr Bryan Langley and the British Film Institute)

17. Frank and Lady Joan Bickerton at ‘The Florida’, 1938. (Courtesy of Miss Rosanna Bickerton)

MAPS

1. Route of the Western Sledging Party, December 1912–January 1913.

2. Routes of the Main Sledging Expeditions, November 1912–February 1913.

3. From Cape Town to Cairo, 1932–33.

Foreword

Come with me, and learn that life is a stone for the teeth to bite on.

Vita Sackville-West, The Edwardians

Any expedition to Antarctica – or, indeed, to any of the world’s most extreme and inhospitable regions – is almost wholly dependent, both for its success and for its ultimate survival, upon teamwork. In an age obsessed with the cult of personality, it is perhaps easy to forget that Scott, Shackleton, Amundsen and Mawson were not titans working in isolation, but leaders of teams. They worked in an environment where temperatures can hover around -40ºC and the wind can maintain an all-year average of 50mph; where, during the winter months, there is no food to be hunted or scavenged; where there are no combustibles to be gathered; and where freezing drift-snow can so disorientate a man that he cannot find a shelter that stands just a few yards away. In these conditions, the man who fuels the stove or minds the storeroom becomes as essential as even the most fêted explorer.

It is in recognition of the vital importance of teamwork that the practice of awarding the Polar Medal en masse to all expedition members has been established. Knighthoods and Royal Geographical Society Founders’ Medals are, by and large, the preserve of expedition leaders, but the award of that small bronze or silver hexagon on its white ribbon acknowledges the essential contributions made by Antarctica’s other, often unsung heroes.

In the case of Sir Douglas Mawson’s Australasian Antarctic Expedition of 1911–14, only Mawson himself, Frank Wild and the master of the Steam Yacht Aurora, John King Davis, had ever been south of the Antarctic Circle. The rest of the crew was made up of enthusiastic novices, some of whom had never even seen snow before. Mawson believed that youth, willingness and a general aptitude were often at least as important as experience. But he also recognised the need for certain specialist skills and knowledge. This is why he recruited men like the Swiss ski champion, Xavier Mertz, and the 22-year-old Englishman, Frank Bickerton – the hero of this book. Every explorer in Antarctica must be an innovator, willing to try new things – new approaches, new ideas and new technologies – if he is to survive. Scott took a balloon and Shackleton a motor car. Mawson journeyed south with an aeroplane and with wireless telegraphy. As the expedition’s mechanical engineer, Frank Bickerton was intimately associated with both of these pioneering experiments. He also led a three-man sledging expedition that discovered the first meteorite ever to be found in the Antarctic – the crucial first step in establishing the continent as one of the world’s richest meteorite fields.

The ‘Heroic Age’ of Antarctic exploration came to an end amidst the mud and blood of the First World War and many of the men associated with it returned only to be lost on the battlefields of Flanders and Gallipoli or in the waters of the Atlantic Ocean. Bickerton served in the trenches and with the Royal Flying Corps on the Western Front. He survived and went on to a variety of other adventures in Europe, North America and Africa and all of these episodes are covered in Stephen Haddelsey’s narrative. But it is, perhaps, as one of the little-known heroes of Antarctica – closely associated with Mawson and Shackleton – that his story achieves its greatest significance. Interest in mankind’s conquest of the Antarctic has not been so intense for the best part of 100 years, with a spate of new biographies and television serials helping to spur the fascination. In this case, entirely new material relating to both Mawson’s AAE and Shackleton’s Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition has also been unearthed – no mean feat in this much-researched field.

It seems to me wholly appropriate that the life of Frank Bickerton should be remembered and celebrated, but not simply for his ground-breaking work on aero-engines and wireless and for his chance discovery of a meteorite. We should acknowledge him as a representative of all those other obscure adventurers without whose courage and sacrifices the great Antarctic continent would be as much of a mystery to us now, in the twenty-first century, as it was to our ancestors in the eighteenth.

Sir Ranulph Fiennes Bt, OBE

Acknowledgements

The extraordinarily varied life of Frank Bickerton has struck a chord in the imagination of practically every individual I have contacted during the long process of researching and writing this book. They have included, as well as family and friends, museum curators, broadcasters, film buffs and Polar and military historians. Many have not only expressed an interest in my subject but have also demonstrated an astonishing willingness to help in shedding light on Bickerton’s numerous adventures. Sometimes their assistance has taken the form of granting me access to family papers or sharing their memories; sometimes it has involved the making of transcriptions of documents in their possession. Without their generosity, this book could never have been written.

I should like to take this opportunity to express my gratitude to all those who have helped and, most particularly, to the following: Karen Bussell for offering to put up a total stranger, for the constant flow of food and drink during my stay and for allowing me unrestricted access to family photographs and papers. David Madigan for transcribing portions of his father’s expedition diaries. Anne Phillips and Elisabeth Dowler for allowing me to read and quote from Aeneas Mackintosh’s Cocos Island diary. Patrick Garland for permission to quote from his father’s RFC diary and for sharing with me his father’s memories of serving with Bickerton during the First World War. The late Nigel Nicolson, for his memories of Bickerton’s visit to the home of his mother, Vita Sackville-West. Anne Fright for permission to quote from the writings of Frank Wild. Trygve Norman for alerting me to the existence of ITAE correspondence in Finse. Angus MacIndoe and Sophia Crawford not only for their memories of Cuthbert and Eileen Orde, but also for allowing the reproduction of Orde’s paintings, drawings and photographs. The late Jean Messervey, Hilda Chaulk-Murray, Chris Woodworth-Lynas and Judith Robertson for casting light on Bickerton’s period in Newfoundland. Robert Stephenson for sharing with me his extensive knowledge of all things Antarctic. Bob Beck, historian of the Pasatiempo Golf Club, for his invaluable help in putting me on to Bickerton’s trail in California. Leif Mills for his help with tracing the friendship of Bickerton and Frank Wild. Bryan Langley and Simon McCallum for background information on the Welwyn Film Studios. Sheila Fairfield, Stephanie Jenkins and Chris Rendle for their help with the Bickertons’ Oxford background. The Mawson family, most particularly Andrew McEwin, Emma McEwin and Gareth Thomas, for permission to quote from the papers of Sir Douglas Mawson. Allan Mornement, for allowing me access to the wonderful diaries of Belgrave Ninnis. Elle Leane for sharing with me her detailed research into the Adelie Blizzard. The late Sally McNally, Elizabeth Pearce, Mrs Didi Cavendish, William Cavendish, Andrew Morritt and the Earl of Shrewsbury for their recollections of Bickerton. John Bell Thomson for help with tracing Bickerton’s Antarctic friendships. Ralph Barker for his help with Bickerton’s RFC career. Mark Offord for his research at the National Archives. Andrew Stevenson for helping me to save and collate the many photographs of Bickerton. My brother, Martin, for his shrewd comments on the shape and content of this book and for struggling through so many drafts.

Of course, the assistance of many institutions and museums has been essential to the completion of this project. For access to documents residing in their care, and for permission to reproduce the same, I am most grateful to: Robert Headland, of the Scott Polar Research Institute; the Syndics of Cambridge University Library; the Mitchell Library; the Royal Geographical Society; the National Archives at Kew; Hull University Archives; the US National Parks Service; the BBC; the British Film Institute; the Museums and Archives Service of Hampshire County Council; the West Sussex Record Office; the Imperial War Museum; the State Library of South Australia; the University of Sydney; the University of Cambridge; the Alexander Turnbull Library; the RAF Museum, Hendon; Stephen Rabson of P&O; and the Canterbury Museum at Christchurch.

Most notably, I should like to acknowledge my debt to Mark Pharaoh, of the Mawson Antarctic Collection in Adelaide, not only for his enthusiastic support and encouragement but also for reading and correcting the chapters covering the Australasian Antarctic Expedition.

Finally, I should like to offer my most sincere thanks to Sir Ranulph Fiennes for his generosity in supporting this book and for providing the foreword; to my editor, Jaqueline Mitchell, for her enormously helpful suggestions and advice at the manuscript stage; and to Bickerton’s daughter, Rosanna, whose help has been crucial to the creation of this testament to her father’s remarkable achievements. This list is not, indeed cannot, be comprehensive and I hope that those who have not been named individually will not think that their help and support is any the less appreciated. Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders and I should like to crave the indulgence of any literary executors or copyright holders where these efforts have been unavailing.

Stephen Haddelsey, Southwell, July 2005

Introduction

my cousin Frank Bickerton … was an ex RAF officer and had been to the South Pole with Amundsen in 1911.

Claude Walmisley, Spacious Days

This brief passage in the privately printed memoirs of a distant relative was the first reference I had ever come across to the name of Frank Bickerton. Given the distance of our relationship – he was my first cousin, three times removed – my ignorance of his career was not, perhaps, particularly surprising. But, now, my curiosity was roused. Why? Because even a casual student of Polar history knows that, while Captain Scott took a Norwegian, Tryggve Gran, on his last, fateful expedition, Amundsen was not accompanied by an Englishman when he made his assault on the fabled South Pole. Had he been so, perhaps the British establishment would have been at fewer pains to denigrate and tarnish his achievement with accusations of duplicity and foul play. If, then, there could be no possibility of a previously unsung British hero sharing the Norwegian’s glory, who was the mysterious Frank Bickerton and why had his name been linked with that of Amundsen?

It soon became clear that, like most flawed reports, Claude Walmisley’s account – though incorrect in a number of its essentials – also contained a kernel of truth. In reality, the closest Bickerton ever came to Amundsen was when the latter donated some of his huskies to the men of the Australasian Antarctic Expedition (AAE), then marooned on the great white continent. Bickerton could make no claim to Amundsen’s laurels, but he had accompanied another ‘Heroic Age’ expedition – led not by a Norwegian but by an Australian named Douglas Mawson. The AAE, however, was never a Pole-seeking expedition; Mawson doubted the value of geographic- polar conquest for its own sake and instead dedicated himself to an exhausting combination of exploration and scientific study of the region as a whole. In particular, he laid great emphasis on geological, meteorological and magnetic observations and insisted on the kind of scientific professionalism and dedication exemplified by Professor Erich von Drygalski on his Gauss expedition of 1901–03. The accomplishments of the AAE have been best summarised by Dr Philip Ayres in his comprehensive 1999 study of Mawson.1 They included, as well as the exploration and survey of 2,600 miles of previously unknown territory, the publication of scientific reports so comprehensive that the multiple volumes they filled were still being compiled and edited nearly thirty years after the return of the expedition. Given these achievements – and the almost unimaginable conditions in which they were obtained – it is not too bold to claim that the expedition was, in many ways, one of the most successful to be undertaken during the whole of the ‘Heroic Age’. Furthermore, it is possible to make the claim without denigrating the attainments of Scott, Shackleton or Amundsen.

Frank Bickerton’s contribution to the success of the AAE can be measured in a number of ways. Most importantly, perhaps, as its mechanical engineer, he was responsible for two of the expedition’s pioneering experiments: with propeller-driven traction and with wireless telegraphy. Although the first did not live up to expectations, as was the case with similar trials with mechanised transport made by Scott and Shackleton, it is perhaps too easy to dismiss the utility of the ‘air-tractor’ and to ignore the fact that its ultimate failure was in large part due to damage done to the machine even before it left the shores of Australia. The use of wireless telegraphy, on the other hand, after initial teething troubles, was altogether more successful. It not only allowed direct communication between an Antarctic station and home, thereby removing much of the doubt and uncertainty resulting from complete isolation, but also enabled the transmission of time signals to determine longitude: an achievement promising huge potential benefits to future sledging parties. Bickerton’s role in establishing, maintaining and operating the wireless station was absolutely crucial to success – as is amply demonstrated in the diaries of the expedition members and Mawson’s official account of the expedition, The Home of the Blizzard, published in two huge tomes in 1915. In the closing days of 1912, he also led the three-man Western Sledging Party which, as well as exploring some 160 miles of uncharted coastline, discovered on 5 December the first meteorite ever to be found in Antarctica. As mechanical ‘odd-job man’ he contributed to the daily viability of the Main Base, which had been located, unintentionally and unknowingly, in one of the most inhospitable corners of the world’s most inhospitable continent. Bickerton’s varied work on the expedition was, therefore, of the greatest importance; but he made another, often ignored but equally vital contribution to its well-being – a contribution made, perhaps, quite unconsciously. In writing of his own battle against the elements on the Kon-Tiki expedition, Thor Heyerdahl noted that ‘No storm-clouds with low pressure and dirty weather held greater menace for us than the danger of psychological cloudburst among six men shut up together for months… . In such circumstances a good joke was often as valuable as a life belt.’2 In the huts of the AAE, battered almost incessantly by winds that gusted at more than 200mph, the same principle held true and, again, diaries and letters reveal that Bickerton’s humour, selflessness and resourcefulness provided no insignificant antidote to the blue devils that inhabit the Antarctic wastes.

The members of the AAE were fêted on their return to civilisation in February 1914. Mawson was knighted and awarded the Founders’ Medal of the Royal Geographical Society (RGS), while all who had ventured into the Antarctic Circle received the King’s Polar Medal or, in the cases of those who had taken part in previous expeditions, bars to their existing medals. But, with the outbreak of the First World War, popular interest in Antarctic exploration rapidly waned and, when it revived, in England the focus was upon the heroic failure of Scott and upon the miraculous survival of Shackleton’s British Imperial Trans-Antarctic, or Endurance, Expedition (ITAE) of 1914–17. Britain’s possessive love affair with the Antarctic, which even Amundsen’s Polar success failed to scotch, remained determinedly nationalistic in focus and there was little room for the consideration of what was seen as a foreign, albeit a Commonwealth, expedition – a strange neglect given that, while the expedition proclaimed itself to be Australian in inspiration, in funding and, by implication, in personnel, there had been a significant British contribution. Although Australian by adoption, Mawson himself was born in Yorkshire and John King Davis – master of the expedition ship, the Aurora – most of her crew, and four of the twenty-five men originally selected for the land parties were all British.

The expedition may have lacked the romantic appeal of an assault on the South Pole, more important perhaps in the first decades of the twentieth century than now, but its story possesses every attribute of great adventure. In a tiny wooden-hulled vessel, Bickerton and his companions braved seas that threatened to overwhelm or crush them; they raised their flags above lands never before trodden by man; they struggled against seemingly insurmountable odds, including weather conditions harsher than those to be found anywhere else in the world; and they faced conflict, madness and death. In battling against these odds and in its achievement of ultimate victory, the AAE was every inch as heroic as the better-known expeditions of the period. Bickerton and his fellows, of whatever nationality, were every bit as tenacious, resilient and courageous as their more famous contemporaries.

The AAE’s photographer and cinematographer was Frank Hurley, now famous for his images of Shackleton’s Endurance in its death throes. Hurley’s photographs show Bickerton as dark complexioned, even saturnine: with a waxed moustache and an intense stare, he could have been a model for Errol Flynn’s screen persona – a man of action, an adventurer, even a buccaneer. By his early twenties, he was already a Fellow of the RGS and had demonstrated a precocious willingness to turn adolescent dreams of exploration and adventure into reality, to become a man in the mould of such characters as Rider Haggard’s Alan Quartermain or W.E. Johns’ Biggles. Bickerton would have laughed at such suggestions but the comparison with fictional heroes is not as far-fetched as it might appear. In the late twenties, frequenting the glittering boudoirs of fashionable London, he became acquainted with the novelists Stella Benson and Vita Sackville-West. While the former fell passionately – and, ultimately, disastrously – in love with him, the latter was so impressed that she took him as the model for the character of the sardonic explorer Leonard Anquetil in her best-selling novel The Edwardians (1930). Nor was this Bickerton’s only appearance in fiction. In 1912, his sister, Dorothea Bussell, included him in her novel The New Wood Nymph, and, as recently as 1989, some of his experiences in the Royal Flying Corps were included in Patrick Garland’s novel The Wings of the Morning.

Given the company he kept, Bickerton’s appearance in fiction is hardly surprising, though any novelist including the full gamut of his adventures might justly fear the incredulity of the audience. His part in the ground-breaking work of the AAE was but one in a series of exploits, any of which might be enough for a ‘normal’ individual. As well as accompanying Mawson’s expedition, he dug for pirate treasure on the legendary Cocos Island in the Pacific Ocean. Shackleton recruited him for the Endurance expedition and he included Hurley, Frank Wild and Aeneas Mackintosh, the ill-fated leader of Shackleton’s Ross Sea Party, among his Antarctic friends. He served in both world wars – as an observer and then fighter pilot in one of the RFC’s elite scout squadrons during the First World War and as an RAF wing commander with a penchant for joyriding over enemy territory during the Second World War – and he was wounded four times, twice seriously. Despite a 40 per cent disability he joined a colony of veterans farming in Newfoundland under the leadership of Victor Campbell, of Scott’s fatal Terra Nova expedition; he helped to found one of California’s most prestigious golf clubs, a magnet for Hollywood glitterati; he travelled the length of Africa by train, plane and automobile; and he worked as an editor and screenwriter for the British film industry during its heyday.

Those who met Bickerton tended to remember him. They were struck, in the first instance, by his piratical looks and adventurous spirit and then, if they grew to know him better, by his modesty and shrewdness. But there are also occasional glimpses of a darker side to his nature; of an unwillingness to suffer fools and of an inability to empathise with those more emotionally susceptible than himself, the result being a capacity to wound, unintentionally, perhaps, but nonetheless deeply. Celebrated diarists such as Stella Benson and Charles Ritchie recorded their impressions of him and their records form a fascinating, if sometimes oddly contradictory portrait. Their descriptions can be further ‘fleshed out’ by the diaries and letters of the men who saw him during some of his most daring adventures, in the Antarctic and over the battlefields of the Western Front. Many refer to Bickerton’s reticence, but it is clear that in the right company – the right company often being that of intelligent women – he could also be a raconteur of no mean ability: ‘Nothing pleased those within his intimate circle more than to get him to tell a story. The material always came from some adventure of his own. Yet he always told the story through the mouth of another. It would usually start: “I once knew a man who …” and then would follow a perfect gem: a narrative not merely exciting in terms of action or suspense, but shrewd in psychological situation and reaction. And always it would be told in short, almost staccato, sentences with the expression of a poker player.’3 His anonymous obituarist in The Times stated that Bickerton ‘could never be persuaded to write his memoirs’ and he laughed at the idea of regular diarising. Sometimes, however, he felt compelled to record his experiences, though not without ironically comparing himself with a tourist who ‘industriously takes photos with a VPK and makes notes on a Utility Scribbling Tablet’.4 Crucially, a number of his writings survive, allowing the reader to immerse himself in the astonishingly vivid and immediate descriptions of his sledging journey across 160 miles of uncharted Antarctic coastline, scribbled in pencil while 70mph winds threatened to shred the tent in which he sheltered; of his engagements with hostile aircraft during the Battle of Ypres; and of his travels through Africa in the early thirties. The existence of these diaries makes it possible not only to tell Bickerton’s story but, in many instances, to tell it in his own words.

Unfortunately, since Bickerton’s surviving diaries are not comprehensive, in completing this book, I can’t help feeling that his tale is, as yet, only partly told. If nothing else, the many months spent in researching and writing about his life have taught me to expect the unexpected, not to be surprised when another previously unsuspected adventure suddenly comes to light. There are still a few small gaps in the chronology and remarkable tales may lie concealed in those nooks and crannies. His obituarist tantalisingly mentions that ‘he did, in recent years and most reluctantly allow notes to be taken at his dictation’ but those autobiographical notes have remained well hidden and one can only wonder about the hair-raising tales that the ageing buccaneer dictated to his amanuensis. For the time being, I can only hope that, in telling the story of this ‘born adventurer’, I might have been able to capture some portion of his intrepidity and, perhaps, to exercise something of his own shrewdness ‘in psychological situation and reaction’.

Author’s Note

All quotations taken from previously unpublished diaries and letters are, so far as possible, reproduced as per the original with punctuation and spelling corrected only where this is essential for reasons of clarity.

One

Of Ice and Treasure

I shall satiate my ardent curiosity with the sight of a part of the world never before visited, and may tread a land never before imprinted by the foot of man.

Mary Shelley, Frankenstein

Saturday 2 December 1911, and, at the port of Hobart, Tasmania, all eyes are trained on the Queen’s Pier where the 600-ton Steam Yacht Aurora is tied up. She’s a businesslike looking vessel: built for strength rather than beauty, with her three slender masts, and the single, tall funnel, rising like a dismembered drainpipe, giving her otherwise-clean lines a slightly ungainly aspect. She sits low in the water, and her decks are crowded precariously with canisters and boxes, stacks of timber and a bewildering assortment of items, of every conceivable size and shape, crammed into all manner of nooks and crannies. Perhaps the most unwieldy is a huge, coffin-shaped crate which the crew mysteriously refer to as the ‘Grasshopper’.

Around the harbour there’s a carnival atmosphere, different from that which prevails at a more routine sailing; the mood is one of almost elated anticipation with excited spectators far outnumbering anxious weeping wives or mothers. The men are in straw boaters and, among the usual seeming chaos of the dockside with its crates and cables, rats and seagulls, grease and dirt, the women shield their best frocks and their nostrils from contamination. Multicoloured bunting is conspicuous in the rigging of neighbouring ships and many of the spectators, young and old, are enthusiastically waving flags. The Aurora flies the pennant of the Royal Thames Yacht Club from her main topmast and the Commonwealth red ensign from her mizzen. The decks of a liner, the SS Westralia, berthed at the King’s Pier just opposite, have been made available to the onlookers, though any gratuities are unlikely to appear in the purser’s ledger. In the harbour, a multitude of smaller craft bob about; a lucky thing since the wharves are so densely packed that some members of the assembly seem in imminent peril of being pushed into the water. Nor is it merely the idle spectators, owners, merchants and families of the crew who are gathered to cheer the Aurora on her way. Among the relaxed, laughing crowd can be spotted public men, standing upon their dignity, and sweating beneath top hats and dark frock-coats. The bright Australian summer sun glances from their gold watch-chains and decorative fobs, and the drooping ostrich feathers in their wives’ hats lend a touch of exoticism to the scene. The Premier, Sir Elliott Lewis, is present, as is His Excellency Sir Harry Barron, the Governor, attended by his aide-de-camp, Major Cadell, and the usual train of flunkies and minor officials. They, of course, are not here out of idle curiosity, but to read out valedictory telegrams and to place the stamp of imperial approval on the very first of Australia’s Antarctic expeditions, to be led by Dr Douglas Mawson of the University of Adelaide. Tall and thin, Mawson conceals his nerves, stretched taut by his, as yet, unaccustomed position of total command, and passes the time in politely, even jovially, responding to the comments and questions of his various supporters. All the time his restless eye is monitoring the feverish preparations for departure. Simultaneously, he turns a deaf ear to the grunts and curses of the crew as they bark their shins and snag their clothing on the clutter strewn about the decks – a clutter which, they are all too aware, gives a distinctly unshipshape appearance to the Aurora.

Tense and expectant though he is, Mawson is willing to abrogate responsibility for the shipboard preparations to the Aurora’s master, John King Davis. Looking, at first glance, more like a haberdasher’s assistant than an intrepid Antarctic veteran, Davis it is who decides precisely what latitude may be allowed the men as they make ready to cast off. Nonetheless, the security of the lashings has a very real interest for Mawson, for in each of those unwieldy crates is housed equipment and supplies upon which success or failure in the Antarctic depends. And he cannot help but mentally calculate the tensile strength of the ropes and tackle as he responds smilingly to another convivial remark or outstretched hand. All of a sudden, the ship shifts at her moorings, causing the landlubbers to take a step to balance themselves, and giving rise to a general alarm that she is about to depart. Many of the shore visitors rush to disembark, fearful of an unscheduled voyage to Antarctica, and it is a few moments before order is restored by the officers’ assurances that notice of departure will be given in due form. At a few minutes to four the warning ‘All visitors on shore’ is heard, and the lazy swirl of smoke from the Aurora’s funnel gives place to a steady, thick black plume, billowing in time with the increasingly determined throb of her engines. The order to let go is given and the green, oily water at her stern begins to boil with the rotation of the tough, four-bladed propeller. The crowd, grown somewhat restive with the imminence of departure, raises a cheer, though Mawson’s pleasure is momentarily checked by the ill-informed shout of some anonymous wag: ‘I hope you bring back the Pole!’ On board, the decks become even more crowded, as those members of the expedition who are to accompany the Aurora to Macquarie Island line the rail and wave and cheer in reply. Among them might be seen the burly figure of Frank Bickerton, strongly and darkly featured, and with a moustache that might grace the upper lip of a cavalry officer or a film star of a later decade. Being an Englishman and a stranger to Australia, he is not the focus of anyone’s particular attention. His upraised hand doesn’t acknowledge any specific handkerchief-wielding matron or girl, but merely offers a general salute to the expedition’s well-wishers.

But the voyage is not yet fully under way, nor have all farewells been spoken. The Hobart Marine Board’s motor launch Egeria, carrying the Governor and his lady, goes as far as Long Point before turning back, while an assorted jumble of other craft follow for a while in the Aurora’s wake. Once the ship is in the channel, the cases of dynamite and rifle cartridges are taken tenderly on board, as the crew of HMS Fantome cheers from across the water. Finally, the Nubeena Quarantine Station is reached and the expedition’s forty-eight Greenland huskies are shipped and tethered round the ship’s bulwarks, howling and whining their reluctance throughout the procedure and no doubt recollecting the trauma of their recent passage from England. As the ship’s head is turned southwards, the lashings are checked again and the expeditioners descend to the wardroom, the adrenalin churning in their blood, as the Aurora’s propeller churns the ocean. At 8.30 p.m. she slips past the signal station at Mount Nelson, and the Morse lamp is used to signal the message, ‘Everything snug on board; ready for anything. Good-bye.’

Frank Bickerton was just 22 years of age when he set sail for the Antarctic. Rather incongruously, a life that was to become extraordinary for its adventurousness and intrepidity had begun in the safe and highly respectable surroundings of suburban Oxford. Born on 15 January 1889, he was the second child of well-to-do, middle-class parents – conservative and ambitious – and hardly the kind of people likely to encourage an only son in the haphazard and dangerous career of an explorer. His father, Joseph Jones Bickerton, was the son of a tobacconist, but he had worked hard to improve the standing of his family and, despite his involvement in a minor electoral scandal in 1880, he had risen to become a councillor and town clerk. He had also reinforced his position as a pillar of Oxford society by linking himself to an impressive array of civic institutions: becoming clerk of the peace, clerk to the Charity Trustees and the Police Committee, and a proctor of the university chancellor’s court. In this last capacity, his name had been linked with that of Oscar Wilde, Bickerton acting as plaintiff’s proctor when Wilde was pursued for non-payment of a bill for Masonic regalia.1 Before their marriage, his second wife, Eliza, had described her 44-year-old fiancé as ‘an elderly looking party’ with ‘a good deal of bald head’ and a ‘cold and formal air’.2 But the Councillor was also a man of action, within a limited sphere, serving as a captain in the Oxford City Yeomanry and contributing to the city’s sporting life by winning a series of rowing trophies with the four-man Endeavour crew.

At the time of his accidental drowning in the waters off Torcross in Devon – his son would later state that he had been ‘murdered by the sea, fetching a small child’s wooden spade that had floated away’3 – Joseph Bickerton’s estate had been worth over £11,000.* In the two years that intervened between the town clerk’s death and that of his wife in 1896, this estate had mysteriously dwindled by nearly half. Years later, Frank’s sister, Dorothea, wrote a semi-autobiographical novel in which she offered a possible explanation for the loss. The heroine’s mother, like Eliza, was from an affluent Devon family and younger than her husband; after his premature death ‘she took up bridge and gambled heavily. She got into debt… . Then, after a few days’ illness, she had died quite suddenly,’4 just as pneumonia had carried off Eliza in only four days. Despite the loss of capital – whether through maternal extravagance or other causes – in financial terms, Frank’s inheritance gave him security and even affluence. In other terms, he seems to have inherited his father’s strength and energy with, at least, a tincture of his mother’s recklessness. Deprived of both parents by the age of 7, he might also have been shorn of the discipline and example that would have focused his abilities.

Frank and Dorothea became the wards of their maternal uncle, Dr Edward Lawrence Fox, a resident of Plymouth, a bachelor and a man of stubborn, mildly eccentric and intellectual habits. From the leafy suburbs of a city steeped in scholarly rigour and industry, the young Bickerton now moved to a port that epitomised England’s traditions of seafaring and adventure. It was from here that the Mayflower, Drake’s Golden Hind and Darwin’s Beagle had sailed. The very house in which Bickerton now lived, 9 Osborne Place, was a mere stone’s throw from the Hoe, where Drake had played his Armada-defying game of bowls; and from his new home’s upper windows the boy could see Boehm’s colossal statue of the buccaneer-cum-admiral staring belligerently out to sea. More recently, the town had become the birthplace of one of Britain’s most celebrated Antarctic explorers: Captain Robert Falcon Scott.

It was in these surroundings that Bickerton’s independent and unconventional spirit began to burgeon. To his guardian’s horror, one of its earliest manifestations was his schoolboy decision to decorate his middle-class forearms with tattoos, a serpent on his right and a bird and snake on his left being, as he later told his great-niece, ‘the best he could afford at the time’.5 All in all, perhaps the attitude of the young Bickerton is best encapsulated in a photograph taken of him when aged about 10. In it he impishly defies Victorian mores by sticking out his tongue at the camera, an early display of the rebelliousness that would characterise much of his subsequent career. Not that such independence was unprecedented: there were intrepid spirits to be found on both sides of his family. His mother’s forebears included a number of diplomatists who had served a budding empire in the far-flung corners of the world and the Bickertons claimed kinship with two admirals, the younger of whom had served under Nelson in the Mediterranean. Perhaps romantic stories of their foreign postings and nautical adventures, told to entertain an orphan in a strange house, had sown the seed – given to the child a desire to abandon the paths more commonly beaten by those of his background and education.

Although his early schooling remains something of a mystery – he may have been tutored at home – in September 1901, Bickerton became a pupil at one of England’s most prestigious public schools: Marlborough College. The usual onward destinations for aspiring young Marlburians included Oxford, Cambridge and Sandhurst but, after only three rather undistinguished years at the college, Bickerton defied any such expectations and instead opted to pursue a career in mechanical engineering. His first step on this path was to embark on a four-year course at London’s City & Guilds (Technical) College. The exact date of his enrolment is uncertain but 1906 seems the most probable year as this would have allowed him to take full advantage of the College’s first series of aeronautics lectures, delivered in 1910. Nonplussed by this unusual choice, his family might have been reassured by the thought that an engineering qualification at least offered the chance of a remunerative profession. After all, his father’s youngest brother, Charles Howard Cotton Bickerton, had pursued a successful engineering career, albeit in the fetid climate of India. It would not be long before they were again forced to review their assumptions. After completing his studies at City & Guilds, Bickerton spent some time working at one of the large iron foundries in Bedford. It was here that he met the intrepid Aeneas Mackintosh, whose mother lived in Bedford and who was, at the time, courting a local girl named Gladys Campbell. Although Mackintosh was ten years Bickerton’s senior, the two men formed a strong and enduring friendship. Already a veteran of Sir Ernest Shackleton’s British Antarctic Expedition (BAE) of 1907–09, Mackintosh was a man of proven daring, even recklessness, and it was under his tutelage that Bickerton’s lust for adventure would at last spill over into action.

On 1 March 1911, the two men sailed on the Royal Mail Steam Packet Oruba, bound for Cocos Island, a jungle-covered rock so steeped in the myths of pirate gold that Robert Louis Stevenson had taken it as the model for his Treasure Island. The tiny island lies 550 miles south-west of the Panama Canal and, according to the legends, the single largest cache hidden there consists of the treasures of the city of Lima. In 1821, faced with the approach of the liberating army of Simon Bolivar, those city dignitaries and ecclesiastics still loyal to Spain rather naively entrusted their bullion to an English sea captain named Thompson, on the understanding that he would hide the treasure on their behalf. Faced with such a temptation – by 1911 the treasure was being valued at £20 million – Thompson cut his cables and ran his brig, the Mary Dier, out to sea. Evading the Peruvian gunboats, he made his way to Cocos Island and buried his ill-gotten gains, adding them to the innumerable other hoards reputedly buried by buccaneers such as Dampier and Bonito the Bloody. Thompson and his crew were later captured by a Peruvian man o’war and all but Thompson, who promised to disclose the whereabouts of the treasure, were summarily executed. The slippery captain then succeeded in eluding his captors and, after various adventures, washed up on the shores of Newfoundland a sick and dying man. For once, he failed to engineer a dramatic escape, and died sometime around 1838 – but not before disseminating, mostly through the offices of an erstwhile shipmate called Keating, enough clues and maps to occupy generations of would-be treasure seekers. It seems to have been one of these maps that prompted Bickerton’s voyage to Cocos Island.

In the years between Thompson’s death and 1911, many expeditions had set out with the intention of retrieving the pirates’ hidden treasure. This one, however, was different for two reasons. Firstly, its sponsors were women, who insisted on safeguarding their investment by accompanying their male business partners. Secondly, they intended to donate their eagerly anticipated discoveries to philanthropic causes, most particularly the establishment of a new London orphanage.

On their voyage southwards, Bickerton and Mackintosh passed the time discussing their enterprise with the former’s RGS acquaintance, the ill-fated explorer of South America, Major Percy Harrison Fawcett. He was on his way to continue his work with the Bolivian Boundary Survey and, as well as telling them of Cocos Island’s history, he further whetted their appetites with stories of another treasure, buried by the Jesuits in Bolivia. Separating from Fawcett at Colón, Bickerton and Mackintosh caught a train to Panama, where they were joined by the expedition’s sponsors, Mrs Barrie Till and Miss Davis, and by the other members of the expedition. These included an American called Stubbins, Colonel Gonzales – the official representative of the Costa Rican government – and a man named Atherton – a resident of Panama whom Mackintosh considered ‘the swiniest swine that ever swanked’.6 After tedious days during which Mackintosh tried, and repeatedly failed, to hire a suitable vessel to carry them to Cocos, and Bickerton fished and went alligator hunting, the party eventually sailed on 8 April on board a cargo steamer, the SS Stanley Dollar, which was to drop them off at Cocos en route to San Francisco. They landed on the island three days later and took up residence in a three-room shack vacated by an earlier expedition. Standing near an inlet, the hut was shaded by palms, and a rich crop of oranges, limes and coconuts weighed down the nearby trees: it seemed as though they had discovered a tropical paradise.

The next few days were spent in rowing round the island in search of likely-looking caves and inlets and in clearing paths through the dense equatorial jungle, searching for the ‘flat stone, with markings on it’7 that the ladies had been told would infallibly lead them to the treasure. No one, apparently, troubled to enquire why anyone possessed of such precise knowledge had failed to retrieve the treasure for themselves. They found no stone, but discovered instead millions of small red ants, which swarmed over them and left them covered with painful bites. They took to blasting their way into rocky outcrops, using dynamite they found in another abandoned tin hut, and all the time squinting at scratches on the rocks, ‘which we all try to shape into anchors, arrows or such-like shapes!’8 After nearly three weeks on the island, tormented by insects of every description and often drenched by tropical storms, with no sign of success, tempers began to fray and all grew tired of ‘this stupid and ridiculous “clue” to the hypothetical Treasure’.9 For Bickerton and Mackintosh, the main, if not the only, pleasure of the expedition became the opportunities they had for exploring the island in each other’s company:

Today being a holiday, Sunday, we were allowed to have it by ourselves. So Bick and I have decided to make a journey up the river as far as we can. At 9 a.m. we started off taking with us some biscuits, tea, jam and sugar, also my compass and aneroid. We have found that the only way of getting anywhere here – if it can be managed – is to go by the river. So we adopted this method and went along, jumping from stone to stone with occasional misses! Which we paid for by getting wet up to the knees… . We took photos as we went along – all the way we passed through the thick tropical vegetation: giant ferns, shrubs that a botanist would revel in but to us it was a wild chaos of growth which it would require someone versed in botany to know the names of. Occasionally we had to scramble over large trees that had fallen and bridged themselves across the river.10

Climbing gradually, after some two hours of travelling they reached a cascade. Above it, they found a large, level plateau which they then proceeded to explore. Thinking the cascade an easy landmark to identify, however, Mackintosh failed to take careful compass bearings. Soon the two explorers were lost and disorientated, hacking their way through

Royal Palms, ferns of every variety – orchids, long grass-like Iris Lily leaves which cut one like a razor if you should happen to scrape along it… . We at this time found ourselves in rather a predicament in not being able to find our way … as we went on we could see no signs, but were getting more and more involved in the mess. Bick climbed the highest trees round, but could get no view of any definite object except a glimpse of the sea, but this did not help us as we did not know in which direction to make for it. After wandering about for at least four hours – hopelessly lost – Bick discovered a decent high tree. Up this he climbed – when at the top he made out the sea and headland to the Northward of us, and what we took to be the High Peak of the island to the SW.11

Proceeding in a northerly direction, they found their way to the cascade and then, via the river, back to the hut, after a ten-hour excursion. Both men agreed that ‘in spite of being wet through and having lost our way’ – for more than five hours – ‘we considered we had spent a most enjoyable day.’

Working days continued in the same vein. They hacked through the equatorial forests in search of likely-looking slabs of rock; blasted holes (on 9 May, ‘Bick swarmed up the rocks and placed the charge and fuse – 14 sticks of dynamite!’12); and rowed into coves which Mackintosh, a ship’s officer, thought impassable to boats laden with treasure but which the ladies considered probable hiding places. All to no avail; relations declined still further, with constant rows and disagreements, and the return of the ship on 13 May came as a relief to them all.

On 10 April, at a time when Bickerton was hacking and blasting his way through the equatorial rainforest of Cocos Island, Douglas Mawson was laying before the Fellows of the Royal Geographical Society in London his plans for a predominantly Australian expedition to Antarctica. As with most expedition leaders of the ‘Heroic Age’ of Antarctic exploration, funding was perhaps the single greatest obstacle he faced and, in addressing the Fellows, he was not only seeking their approval but also making a direct appeal to their generosity. His Antarctic credentials were such that he could expect to command the undivided attention of his auditors. In March 1909, aged just 26, he had returned from Shackleton’s BAE, having completed a record-breaking 1,260-mile unsupported man-hauled sledging journey in his quest for the South Magnetic Pole. He had also made the first ascent of the volcanic Mount Erebus and drawn the most accurate map of South Victoria Land to that date.

The area of Antarctic coast that he now wished to explore stretched from Cape Adare, directly to the south of New Zealand and the westernmost point of Captain Scott’s Terra Nova expedition, to the Gaussberg, south of the Indian Ocean and the easternmost line of Professor Erich von Drygalski’s German expedition of 1901–03. Only one landing, lasting but a few minutes, had been made in his chosen area: by the French expedition led by Dumont D’Urville of the Astrolabe in January 1840. Naming the region after his wife, D’Urville called it Terre Adélie or, in its anglicised form, Adelie Land. The only other expeditions that had ventured into the same region were those led by the Englishmen John Biscoe (1830) and John Balleny (1838–39) and the United States Exploring Expedition, led by Charles Wilkes of the Vincennes between 1838 and 1842. To all intents and purposes, then, a stretch of virgin territory some 2,000 miles wide lay facing Australia across the great Southern Ocean. Mawson’s objective was to explore it, chart it, and to undertake a detailed scientific analysis of its climatic and magnetic phenomena, its meteorology and its geology. In addition, the expedition’s vessel would carry out detailed oceanographic work on its way to and from the site of the expedition’s Main Base.

Mawson’s lecture was a huge success – a success that is, in all ways but one: while he had fired the imaginations of many of his listeners, he only managed to persuade the RGS to subscribe £500 to the expedition’s kitty. Though not in itself ungenerous, this contribution made only very small inroads into the £45,000 that he estimated the expedition would cost. In his fund-raising speeches and private applications an assortment of justifications rubbed shoulders: the possible existence of rich mineral deposits, the advancement of science, and the need for Australia to stake its claim in Antarctica before it was gazumped by a more aggressive and less scrupulous imperial power. In Sydney, Mawson’s friend and supporter, Professor Edgeworth David, even went so far as to compare ‘Dr Mawson’s objective with the Yukon, and suggested that large discoveries of gold were possible’.13 For all their passion, however, these appeals had an Achilles’ heel: they lacked the glamour attaching to an attempt on the geographic South Pole. As a geologist, Mawson saw little of interest in such a conquest, preferring instead to dedicate his resources to the rigorous scientific study of the region. This meant that, in marketing his expedition, he must find other means by which to appeal to donors seeking a cause célèbre, particularly the wealthy Australians attending the coronation of King George V. One way to capture the attention of both public and sponsors was to include, and advertise, the use of innovative technology in his plans. It was these plans that would soon involve Bickerton in one of Antarctic exploration’s most daring experiments to date.

In 1908, The Sphere14 had challenged ‘motorists, submariners, bear-drivers, and aeronauts’ to better the record of 460 miles from the Pole and, although that objective remained firmly outside Mawson’s field of interest, the challenge and its popular appeal would not have been lost on him. Shackleton, a self-publicist nonpareil, had long ago impressed upon him the importance of capturing the public imagination. He had also shown him that mechanised transport could be used for this purpose by taking on the BAE a 15hp Arroll-Johnston motor car, donated by William Beardmore, the Clydeside shipbuilder, after whom a glacier was dutifully named. More recently, in January 1911, Scott’s Terra Nova had unloaded at McMurdo Sound three tracked motor sledges designed by the Wolseley Company of Birmingham. In both cases, publicity had been as much a consideration as utility.

Perhaps inspired by the Antarctic balloon flights made during Scott’s National Antarctic (Discovery) Expedition on 4 February 1902 and during Drygalski’s Gauss expedition two months later, Mawson decided that he would be the first to take an aeroplane to the Antarctic. Scott’s balloon, quaintly named the Eva, had cost an extravagant £1,300 and, at the edge of the Great Ice Barrier, it had made two flights, reaching a maximum altitude of 800 feet. But the balloon had leaked and its further use was abandoned. Drygalski’s ascent had been rather more successful, reaching 1,600 feet. There were, however, huge risks inherent in such experiments and these had been amply demonstrated in 1897 when, in an attempt to cross the North Pole in a balloon called the Ornan, the Swedish aeronaut Salomon Andrée and his two companions died of exposure. Their bodies wouldn’t be discovered until 1930. But no expedition to the Antarctic was devoid of danger and Mawson, convinced that the benefits – not least in terms of publicity – would more than outweigh the risks, remained bent on achieving Antarctica’s first powered flight. With this aim in mind, he purchased an REP monoplane from the Vickers Company for £955 4s 8d. An obvious use for an aeroplane in the Antarctic would be spotting leads, or channels, in the ice wide enough for the expedition ship to push through, but since Mawson’s machine would have to be transported in a crate, there would be little chance of utilising it in that way. Besides, the problems of launching an aeroplane from a ship would not be seriously addressed until the exigencies of war led to systematic research under the auspices of the Royal Naval Air Service. Once assembled at the spot chosen for the expedition’s Main Base, however, the monoplane could be used for reconnaissance and survey work.

Such an experiment – an astonishingly daring one given that Louis Blériot’s pioneering cross-Channel flight had only taken place in July 1909 and that, in 1911, no one had ever taken off from ice or snow – required the recruitment of men with very particular skills and experience. The expedition staff of thirty was to be made up almost entirely of graduates from the universities of Adelaide, Sydney and Melbourne, but Mawson recognised that in Australia, a country that had not witnessed its first powered flight until Houdini’s exploit at Digger’s Rest in March 1910, aviators were likely to prove rather thin on the ground. In making up the shortfall, he demonstrated a willingness to listen to the advice of friends and colleagues in England. Kathleen Scott, wife of Captain Scott and herself an aviation enthusiast, assisted him not only in the choice of an aeroplane, but also in the selection of a pilot: Lieutenant Hugh Evelyn Watkins of the 3rd Battalion, the Essex Regiment. Although a competent mechanic himself, Watkins would need the assistance of another engineer to maintain the machine in Antarctic conditions. The man selected for this role was Bickerton, who volunteered for the expedition immediately upon his return from Cocos Island.

Although Bickerton had been unable to attend Mawson’s address at the RGS in April, the two did meet through their mutual acquaintances among the Society’s Fellows. Bickerton’s application for a Fellowship, made in October 1910, had been the first real demonstration of his interest in exploration and, despite his inexperience, he had articulated his enthusiasm sufficiently well for his two sponsors, William Scoresby Routledge and Edward A. Reeves, to agree that he was ‘likely to become a useful and valuable Fellow’. Australian by birth, Routledge was husband to Katherine Pease Routledge (the surveyor of Easter Island) and descendant of the redoubtable whaler and father of Arctic science, William Scoresby. He was also irascible and cantankerous: he lacked friends at the best of times and there is no evidence of an acquaintance with Mawson. Indeed, he may not even have been acquainted with Bickerton, as the Society’s regulations required that only one of an applicant’s two sponsors should know him personally.

Reeves was a very different character: a family man, a lifelong servant of the RGS and a committed spiritualist, he had also been of immeasurable service to Mawson in obtaining for the AAE a loan of specialist surveying equipment to a value of £439 4s