Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

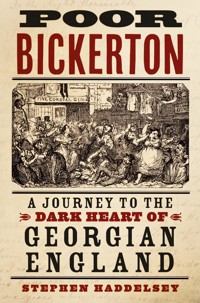

'An adroit, intelligent and painstaking social history … Poor Bickerton offers us a luxurious tapestry from which everyone interested in English social history in the late-Georgian period can learn something new and surprising.' – Professor Jerry White, author of London in the Eighteenth Century: A Great and Monstrous Thing On 8 October 1833, Coroner Thomas Higgs opened an inquest into the death of John Bickerton, an elderly eccentric who, despite rumours of his wealth and high connections, had died in abject squalor, 'from the want of the common necessaries of life'. Over the coming hours, Higgs and his jury would unpick the details of Bickerton's strange, sad story: a story that began with comparative wealth, included education at Oxford and the Inns of Court, and brought him to the attention of two sitting prime ministers, but which descended into madness, imprisonment, mockery and starvation. Using Bickerton's life as a thread around which to weave his narrative, historian Stephen Haddelsey explores the lives of the down-and-outs and rejects of Georgian and Regency England, including debtors, criminals and the insane. For anyone fascinated by this era of balls and intrigue, of Lord Byron and mad King George, here a world altogether grittier than that to be found in the novels of Jane Austen is revealed in all its lurid detail.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 379

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The excellent Lord Verulam has noted it, as one of the great deficiencies of biographical history, that it is, for the most part, confined to the actions of kings, princes, and great personages, who are necessarily few; while the memory of less conspicuous, though good men, has been no better preserved, than by vague reports, and barren elogies.

Sir John Hawkins, ‘The Life of Mr Isaac Walton’, The Complete Angler (1760 edition)

Derangement assumes a thousand different shapes, as various as the shades of human character.

Leonard Shelford, A Practical Treatise of the Law Concerning Lunatics (1847)

And thought shall turn, poor Bickerton, to thee!

James Shergold Boone, The Oxford Spy (1818–19)

In memory of my father,Michael Noel Haddelsey,who taught me to conjure a Roman forum from a pile of rubble.

First published 2024

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Stephen Haddelsey, 2024

The right of Stephen Haddelsey to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 426 0

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

Contents

Foreword by Professor Jerry White

Acknowledgements

Family Tree

Introduction

1 A Death in Westminster

2 Origins

3 An Incident at St James’s Palace

4 Bow Street

5 The House of Correction

6 Lunatic?

7 Middle Temple to Hertford College

8 Place-Seeker

9 Debtor

10 Death and Resurrection

Notes

Bibliography

Foreword

Attempting to rescue the lives of obscure individuals from the indifference of posterity is one of the most difficult tasks historians can set themselves. Until recently it usually took some small trigger of notoriety to bring a name to our attention in documents and newspapers, though now the infinite resources available to family historians has meant that we can all claim ancestors to be sought out in the public records and made an object of study. Both those factors are inspirations in the case of Stephen Haddelsey’s intriguing study of John Bickerton.

‘Poor Bickerton’ had been an object of some wonder at various times in his long life, and the tragic circumstances of his death were sufficient to endow him with more than a brief footnote in the periodicals of the 1830s; and Bickerton happens to be reputedly connected to the historian’s own family, so Haddelsey was familiar with a copy of Bickerton’s portrait as an heirloom. But having inspiration for a project is one thing, bringing it to a triumphant conclusion as Stephen Haddelsey has done here is quite another.

John Bickerton was an exceptional eccentric. Born into yeoman prosperity in deeply rural Shropshire in 1755, he ended his days starved and neglected on the bare floor of one of London’s many slum rooms, some seventy-eight years later. How he travelled from one place to the other, with an interrupted university education in both Oxford and Cambridge, a spell attached to organised religion sufficient for him to describe himself as ‘the Reverend’ and a loose attachment to the law that made him known as ‘Counsellor’, is the stuff of Bickerton’s life story. It is as weird as any history of Don Quixote and with some of the same characteristics.

Delusional paranoia drove Bickerton to reinvent himself in a new guise at different periods of his life. Throughout, he was marked for attention by his oddity and his inability – or unwillingness – to conform to ‘normal’ expectations of behaviour. His life in Oxford – that enduring agglomeration of wayward misfits – found him among people even more odd than he. Yet, as Haddelsey brilliantly shows, oddity and nonconformity were all around him, even if frequently buried under surface respectability, from the governor of the gaol, where he was kept for a time in preventive detention, to the coroner who sat on his inquest.

As this indicates, Poor Bickerton tells far more than the story of one unconformable character. It is an adroit, intelligent and painstaking social history of the world in which John Bickerton lived and died. Haddelsey follows every lead to delve deeply into the many institutions and individuals impacting on Bickerton’s troubled history. He takes us into the hidden corners of London and Oxford, into the precarious uncertainties of the criminal justice system, into prisons for both miscreants and debtors, into Inns of Court and Oxford colleges, into the contemporary understanding of madness and the good and bad among private madhouses, and into the slums of early nineteenth-century London and the semi-derelict plague house of Tothill Fields, where Bickerton breathed his last. It is all done with rare scholarship and a true feeling for past realities. In all, Poor Bickerton offers us a luxurious tapestry from which everyone interested in English social history in the late Georgian period can learn something new and surprising.

Jerry White

Emeritus Professor of Modern London History

Birkbeck, University of London

Acknowledgements

All historians owe an enormous debt to the archivists and librarians who preserve and make available the documents in their care. I am no exception, and I would like to offer my sincere thanks to the following individuals and organisations who have responded so helpfully to my enquiries regarding the life and career of John Bickerton and the world that he inhabited: Amber Druce, Curator of Social History, Blaise Museum, and Bristol Museum and Art Gallery; Katy Green, Archivist at Magdalene College, Cambridge; Victoria Hildreth, Assistant Archivist to the Honourable Society of the Middle Temple, London; Oliver House, Superintendent, Special Collections, the Bodleian Library; James Howarth, Librarian at St Edmund College, Oxford; Andrew Lott, Senior Information Officer, London Metropolitan Archives; Saffron Mackay, Library and Archives Assistant, Royal College of Surgeons; Janet Payne, Archivist at Apothecaries’ Hall; Matthew Payne, Keeper of the Muniments, Westminster Abbey; Helen Sumping, Archivist of Brasenose College, Oxford; Karen Young, Alison Mussell and Nathaniel Stevenson of the Shropshire Archives; and the staff of The National Archives in Kew.

I would also like to express my particular gratitude to: Professor Jerry White for his generous help and support, and for kindly agreeing to write a foreword to this book; my brother Martin for his typically astute remarks on the draft text; my niece Anna for her endeavours in The National Archives, Kew; Oliver Richardson of the Wem Civic Society; and Margaret Markland, who very kindly provided not only a transcription of the memorial inscriptions in the churchyard of St Peter’s in Myddle, Shropshire, but also took the trouble to visit the churchyard in order to photograph the headstones.

Finally, I must thank my wife Caroline and my son George for their patience when listening to my accounts, not only of family history, but of the trials and tribulations associated with my quixotic quest for the minutest of details relating to the strange life of John Bickerton; as always, they have displayed Herculean resilience.

Stephen Haddelsey

Family Tree

Introduction

Though almost entirely forgotten today, during his lifetime, and for several decades afterwards, John Bickerton, or ‘Counsellor Bickerton’, as many called him, was a known character of early nineteenth-century Oxford. He was written about in prose and verse during his lifetime, and his death resulted in a number of lengthy notices in The Gentleman’s Magazine and elsewhere. The question is, why? What led memorialists, journalists, poets and artists to commemorate a man who, as far as we can tell, was neither exceptionally talented, influential nor vocal? A man, moreover, about whom, in real terms, they knew practically nothing.

Born to comparative affluence and well educated – he studied at Cambridge, Oxford and the Inns of Court in London – Bickerton ended his life in abject squalor, ‘from the want of the common necessaries of life’.1 There is, however, nothing of the parable in his story: no opportunity for a moralist to point the finger and tell his audience, ‘learn from this man’s mistakes, his flaws, or his hubris’. Instead, for many years, he led a quiet, apparently studious existence, well away from the public gaze.

But he was also subject to increasingly severe bouts of mental illness which, over time, made it difficult for him to provide for himself; his eccentricities grew ever more pronounced, so that he became at best a curiosity, and at worst, the butt of cruel or unthinking humorists. Reporting on Bickerton’s demise, one angry journalist berated the Westminster authorities for their failure to help the ailing eccentric in his last days, but his was a voice crying in the wilderness, and the story of the old man’s miserable end was not picked up as a cause célèbre by social reformers seeking to improve the provision of poor relief.

While some elements of his biography were correctly reported after his death, the facts were alloyed with pure fiction, and no one appears to have devoted much time to investigating the genuine circumstances of Bickerton’s life and death. His contemporaries described him variously as ‘poor’, ‘eccentric’, ‘singular’ and ‘unhappy’ but none sought to explain his oddness, being satisfied that the oddness itself made him worthy of observation.

Is it Bickerton’s oddity that makes him worthy still of consideration nearly two centuries after his death? In part, the honest answer must be ‘yes’. The descriptions of his life, death and peculiarities catch our attention, just as the man himself caught the attention of those with whom he came into contact, no matter how fleetingly. But there is more to it than that. By tracing Bickerton’s footsteps from rural Shropshire to the universities of Cambridge and Oxford, from Oxford to the Inns of Court, into Bow Street Magistrates’ Court, through the portals of two prisons and, ultimately, to the squalid ruins of a derelict pest-house, it is possible to see something of late Georgian and Regency England, albeit through a glass darkly. For, while Bickerton’s life may have been exceptional when taken in the round, facets of his experience, including the most demeaning, were common to many – as we shall see.

During Bickerton’s own time, John Wight, a journalist who reported on hearings at Bow Street, thought it important for his readers to be:

… made acquainted with the states and conditions of human nature, with which, from the sympathy due to the more unfortunate part of the species, he should not be entirely ignorant; it is by such means alone that the prosperous and more orderly portion of society can know what passes among the destitute and disorderly portion of it; that they can rightly appreciate the advantages they enjoy.2

In this context, we might almost think of Bickerton as we think of some of the minor characters in the novels of Charles Dickens: it is their very abnormality – their marked deviation from the accepted norms of behaviour – that makes them not only fascinating but also an essential part of our perception of the wider world they – and he – inhabited. Through the pursuit of such misfits, we gain access to parts of a world that might otherwise remain entirely invisible to us. At the same time, an examination of Bickerton’s life and experiences might very well lead us to accept that some of Dickens’ characters were not as remote from reality as we might once have thought.

Bickerton was born in 1755, during the reign of King George II; he would live through seventy-eight of the Georgian era’s 123 years, witnessing the entire reigns of George III and George IV, and dying less than four years before the accession of Queen Victoria. In many respects, the age into which he was born was a violent one. The Bloody Code – the laws of England, Wales and Ireland that mandated the death penalty for crimes ranging from treason to the theft of property worth more than 12 pence – would reach its zenith during his lifetime, with no fewer than 220 offences made punishable by death by 1800 – more than a fourfold increase since 1689. Branding, flogging and pillorying remained on the statute books until well into the nineteenth century, while imprisonment for debt was commonplace, with some 10,000 individuals imprisoned every year, often for very small sums. As far as the treatment of the insane was concerned – and Bickerton was certainly considered mad by many of his contemporaries – conditions were all too often degrading and wilfully cruel, with the unfortunate inmates of Bethlem Hospital displayed to paying spectators as late as the 1780s.

As the following pages will show, Bickerton had the misfortune to experience first-hand some of Georgian England’s worst horrors, and yet the period through which he lived was also one of positive change. By the late eighteenth century, the more brutal forms of corporal punishment were viewed with increasing abhorrence, and the Bloody Code itself came to an end in 1823 when the passing of the Judgment of Death Act made the death penalty discretionary instead of mandatory for most crimes.

Both of the prisons in which Bickerton was incarcerated were new structures, designed according to the recommendations of social reformers like the Calvinist John Howard – after whom the Howard League for Penal Reform was named – and built to replace the dark, dank and disease-ridden medieval gaols that the Georgians had inherited. The appalling treatment of the insane, too, had become a matter of public scandal, with many demanding that asylums should be regularly inspected – demands that ultimately resulted in the creation of the Lunacy Commission in 1828.

Another piece of Georgian legislation, the Anatomy Act of 1832, brought an end to a further source of outrage in Georgian society – the illegal trade of the body-snatchers, or resurrection men. Ironically, while the timing of the Act removed the risk of Bickerton’s body being ‘snatched’, its clauses actually increased the risk of his being anatomised after death – snatching and anatomisation both falling to the lot of his friend, Demetriades, the Greek.

Of course, none of these innovations constituted a panacea. New prison buildings, even those built to the latest design, did not necessarily beget a revision in the attitudes of those who ran the institutions, as Bickerton would discover when he was placed in the ‘care’ of Thomas Aris, Governor of Coldbath Fields House of Correction. Victorian asylums for the insane, meanwhile, would themselves become bywords for neglect; while that last great throw of the dice of Georgian reformers, the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834, would become infamous for its inhumanity – thanks in no small part to the writings of Charles Dickens.

On balance, then, it is probably true that Bickerton experienced very few of the benefits of Georgian innovation, whether social, penal, medical or judicial: a reality brought home most poignantly, perhaps, by the fact that he died in the near-derelict remains of a seventeenth-century plague hospital in Westminster – a ruin that not only survived the swelling tide of Georgian urbanisation but would outlive the Georgian age altogether.

I first became aware of Bickerton through Burt’s sensitive portrait of 1818, a copy of which hung in the drawing room of my paternal grandfather, Noel Henry Fitzwilliam Haddelsey. His grandmother, Alice Emily, was a Bickerton by birth and the portrait had passed through the family for generations. The exact relationship between John Bickerton and my family remains unclear – though Alice Emily’s elder brother, Joseph Jones Bickerton, Liberal councillor and Town Clerk of Oxford, certainly claimed him as a relative.

The surviving facts of his life I have gathered from a multitude of sources, both published and unpublished. Though it seems highly improbable that we will ever really ‘know’ Bickerton, I hope that this book will at least endow him with greater substance and serve to dispel some of the myths surrounding his troubled existence. With Bickerton as their guide, readers might also discover at least something of a Georgian and Regency England altogether grittier than that to be found in the novels of his contemporary, Jane Austen.

1

A Death in Westminster

At eight o’clock on the evening of Tuesday, 8 October 1833, Mr Thomas Higgs, Coroner to the Duchy of Lancaster and Deputy Coroner for Westminster, called for an end to the hemming and hawing, the chatter and the laughter inseparable from any public gathering, so that he might open, with due ceremony, an inquest into the death of John Bickerton of the Five Chimneys, Tothill Fields, Westminster.

Having enforced silence, Higgs turned his attention to the prospective jurors herded in by the parish Beadle: his task, to choose at least twelve – and no more than twenty-three – all male, certainly, preferably local freeholders, ‘good and honest’ and not foreigners, convicts or outlaws. Otherwise, their only definite similarity was their inability, or unwillingness, to bribe the Beadle and thereby dodge the summons to serve – a practice so common among the moneyed classes that most coroners’ juries were made up almost exclusively of tradesmen and shopkeepers, with the gentry and professional classes made conspicuous by their absence.

After he had completed both his selection and the process of swearing-in, Higgs, his twelve jurymen and the usual ragtag crowd of idlers and newspapermen attendant upon any inquest then walked the short distance from the Crown and Sceptre, a public house located at the junction of Douglas Street and Chapter Street, to the dead man’s residence.1 Without the benefit of a public morgue (London’s first would not be opened until 1856, in St Anne, Soho), until fairly recently most coroners had required that the body of the deceased should be moved to the site of the inquest – commonly, as in this case, a local inn, but also, on occasion, a barn, private residence or anywhere immediately available and sufficiently large for a public hearing – where it would lie throughout the proceedings. On this occasion, though, it had been left at the place of death, perhaps because the two buildings lay in such close proximity to one another, but more probably because the autumn of 1833 was proving unseasonably warm and neither Higgs nor his jury wished to have their nostrils assailed by the stench of putrefaction during their deliberations.

Fortunately, Higgs was not setting a precedent: while it had long been held that the presence of the corpse underpinned the authority of a coroner’s inquest – indeed, Tudor legislation demanded that ‘the body should lie before the jury during the whole of the inquiry’2 – in practice, it was no longer considered mandatory to keep the body under the eyes (and noses) of the jury throughout the proceedings.3 But, whatever the weather conditions and ambient temperature, an inspection of the body by the jury could not be avoided: without it, an inquest could – and almost certainly would – be declared invalid.

In crossing Chapter Street, the coroner and his entourage moved from one of the newer buildings in Tothill Fields to one of its oldest and most dilapidated.4 In the medieval period, the fields – a marshy tract of land located between Millbank and Westminster Abbey – had been home to a number of noblemen, whose halls could be found scattered across an otherwise sparsely populated wasteland. The Elizabethan antiquarian John Stow notes that, in 1256, Sir John Maunsell, Chancellor to Henry III, invited the kings and queens of both England and Scotland, as well as their courts, to his house in Tothill Fields, but his guests proved so numerous ‘that his house at Totehill [sic] could not receive them’ and he was ‘forced to set up tents and pavilions to receive his guests, whereof there was such a multitude that seven hundred messes of meat did not serve for the first dinner’.5

Jousts and trial by combat are known to have taken place here, with one of London’s earliest chroniclers observing that in 1441, ‘yere whas a fyt at the Totehill betwixte two thefes a peller [thieves appellant] and a defendaunt. And the pellar had the ffelde and victory of the defendaunt within thre strokys’.6 Duels, too, were fought here throughout the seventeenth century, with the last recorded occurring on 9 May 1711 when Sir Cholmley Dering and Colonel Richard Thornhill faced each other with swords and pistols after Dering had physically assaulted the colonel during a violent quarrel. ‘They fought at sword and pistol this morning in Tuttle Fields,’ Jonathan Swift told Stella, ‘their pistols so near, that the muzzles touched. Thornhill discharged first, and Dering having received the shot, discharged his pistol as he was falling, so it went into the Air.’7 Dering died some hours later after admitting his guilt in the affair and forgiving his adversary.

Even as late as 1757, Tothill Fields was still being chosen as the ground for the determination of civil suits by force of arms, with two gentlemen, William Kent and Richard Allen, both ‘furnished with competent armour’, expected to fight in order to settle a land dispute. Kent, it appears, decided that discretion was the better part of valour and, when ‘solemnly called’, he did not grace the field with his presence, thereby surrendering his claim.8

Tothill Fields was also a spot where, traditionally, convicted necromancers were forced to watch the destruction of their instruments and talismans. In the reign of Richard I (1189–99), for instance, Ralph of Wigtoft, clerk or chaplain to Geoffrey, Archbishop of York, ‘had provided a girdle and ring, cunningly intoxicated, wherewith he meant to have destroyed Simon [the Dean of York] and others; but his messenger was intercepted, and his girdle and ring burned at this place before the people’.9 Perhaps claiming benefit of clergy, and no doubt reminding the court that his master was half-brother to the king,* the unscrupulous Wigtoft appears to have suffered no punishment for dabbling in witchcraft, going on instead to involve himself in various other nefarious acts and dying peacefully in his bed in Rome around 1196 – though not before confessing to the Pope ‘that he had acquired many false letters in the Roman court, both about the business of his master, the Archbishop of York, and about his own business’.10

On another occasion, in Edward III’s reign (1327–77), a culprit caught ‘practising with a dead man’s head’ was ‘brought to the bar at the King’s Bench, where, after abjuration of his art, his trinkets were taken from him, carried to Tothill, and burned before his face’.11 Whether the head was counted among the incinerated trinkets is not stated. The records of the Royal College of Physicians confirm that, in the reign of Queen Mary, the ‘unwholesome and sophisticated remedies’ of quacks were still being burned in the open market at Westminster and this could have been at either Tothill or outside Westminster Hall.12

In the seventeenth century, the chronicler James Heath tells us that, following the destruction of the Royalist army at the Battle of Worcester on 3 September 1651, thousands of Scottish prisoners were ‘driven like a herd of swine through Westminster to Tuthill Fields’,13 where they were held prior to being sent to New England as bondservants.14 Subjected to harsh treatment and riddled with disease, many did not survive long enough to be transported, and the parish records of St Margaret’s, Westminster, include reference to a payment of ‘thirty shillings for sixty-seven loads of soil laid on the graves of Tothill Fields, wherein the Scotch prisoners are buried’.15

The Scottish prisoners of war would not be the last to be interred here because the emptiness and comparative remoteness of Tothill Fields made it an ideal spot for another essential activity: the housing of plague victims. Severe outbreaks of plague in 1603, 1625 and 1636 had finally convinced the Westminster authorities that the city required its own dedicated pest houses rather than temporary hospitals, and some sources suggest that the pest house in Tothill Fields may have been erected as early as 1638, though others give 1644 and even 1665 as the years of construction.

The seventeenth-century physician and botanist Nicholas Culpeper comments that parsley, which ‘rejoices in barren, sandy, moist places […] may be found plentifully about Hampstead Heath, Hyde Park, and in Tothill-fields’,16 and it might even be the case that the abundance of this herb, which was well known for its ability to eliminate or at least mask bad odours, was one of the reasons for the choice of Tothill Fields. What all accounts agree on is that the pest house at Tothill was a substantial building (or collection of buildings), and not one of the ephemeral ‘pest sheds’ relied upon elsewhere.

The fact of its being so well constructed appears to support a suggestion in the Mirror of Literature for 1823, that it was not purpose-built, but that ‘several houses, which stood apart from the rest, were appropriated as pest-houses’.17 The surviving images, the last of which date to the 1840s, show the building to have been a large gabled structure made of stone, with two storeys and multiple chimneys of great size. Indeed, it is so substantial that it seems quite possible that the ruin in which Bickerton died might have begun its life as the home of one of the noblemen mentioned by Stow.

To add to the grimness of the location, those who died in the pest house could expect to be buried there, with Samuel Pepys recording on 18 July 1665 that he felt ‘much troubled this day to hear at Westminster how the officers do bury the dead in the open Tuttle-fields, pretending want of room elsewhere’.18 Daniel Defoe tells us that only 159 plague victims were buried at Tothill Fields;19 nonetheless, the fear of ‘pernicious exhalations’ and the fact that the burial ground was unconsecrated only served to darken the area’s reputation still further.

Towards the end of the eighteenth century, the buildings had been converted for use as almshouses for ‘twelve aged married couples’.20 If, as was commonly the case, the almshouses bore the name of the benefactor who had dedicated them to charitable use, that name has long been lost to time, and the buildings had become known commonly as the ‘Seven Chimneys’, the ‘Five Houses’ or a conflation of the two, the ‘Five Chimneys’. Soon afterwards, they appear to have changed use again, being divided into a number of private dwellings – though one contemporary thought it ‘somewhat remarkable that houses built for such a purpose as refuge from pestilence should have been allowed to remain to our time; since it might have been expected that popular prejudice would long since have condemned the buildings as unfit for habitation’.21

In 1823, an observer described what remained of the pest house as ‘an antique looking row of red brick dwellings […] inhabited by poor people’.22 A more romantically inclined writer for The Builder magazine of 1832 remarked, ‘With the moss and lichens growing on the roofs and walls, and their generally old-fashioned quaintness, a very small stretch of the imagination removed the buildings which had surrounded them even then and brought them once more into the open ground’.23

In fact, to those not in search of the picturesque, the Five Chimneys were less houses than hovels. A reporter who accompanied Thomas Higgs found not quaintness but abject squalor, noting that the building in which Bickerton’s body still lay ‘had neither windows nor doors, and part of the walls nothing more than loose bricks piled together’.24

Once inside, the coroner and jurors found little enough to inspect. Bickerton remained where he had died, on the dusty, rubble-strewn floor of a room otherwise utterly devoid of interest and with no furnishings of any kind. Besides the naked corpse – that of an emaciated elderly man, his ‘bones nearly protruding through the skin’25 – the only objects in the dark, low-ceilinged chamber consisted of a shabby wig and gown such as a barrister might once have worn in court. After a cursory examination, the whole party beat a hasty retreat, some expressing ‘their astonishment that any individual could live in such a miserable hovel’,26 and all glad to return to the comforts of the Crown and Sceptre, which, in comparison with the Five Chimneys, seemed little short of palatial. Now, having viewed the body and the place of death, the jury could at last turn their minds to the events surrounding Bickerton’s demise.

It transpired that two days before, during the early evening of Sunday, 6 October, Police Constable Burke of ‘B’ Division of the newly established Metropolitan Police Service had been patrolling his beat on the Vauxhall Bridge Road when a party of gentlemen approached him to ask that he ‘remove a crowd of boys and women who were disturbing the dying moments of an old man in an empty house’.27 Burke accompanied the party to the Five Chimneys and, with their aid and that of some residents, at last succeeded in dispersing a raucous group of idlers who had gathered outside Bickerton’s squalid rooms. On entering, the constable had discovered the old man alive, but in all other respects just as the jury had seen him, lying naked on the earthen floor, ‘He was to all appearance in a dying state, and not a person to assist him in his last moments. Nourishment was immediately procured, as the poor creature appeared to be quite helpless and imbecile, and nearly starved to death.’28

Bickerton’s next-door neighbour, a young ivory-turner named Charles Rice, had entered the room with Burke and, kneeling next to the sick man, had asked him how he was:

He replied that he was as bad as he could be to be alive. He had not strength to put his own clothes over him he was so exhausted. Witness seeing him in such a wretched helpless state, went out and got him some tea. He said, ‘I am too far gone for that or anything else.’ By persuasion he took about two sips of the tea, but immediately threw it off his stomach, remarking, ‘Now you see I cannot drink that or anything else’.29

Concerned neighbours – all of them very poor – brought alternative food and drink, which the old man refused to taste, and a Mr M’Carthy sent for a surgeon and provided a straw mattress so that he might at least lie in more comfort. Rice, meanwhile, ‘in the kindest manner’, offered to sit with him all night.

According to Rice’s testimony, the only event of note that occurred during the hours of his vigil was when Bickerton ‘gave him a packet of papers which he desired him to send to a Mrs Wood, at Wens [sic], in Shropshire, after he was dead’.30 This Mrs Wood, whom Bickerton declared was to be ‘the sole successoress of all that he was possessed of’,31 was his niece, Elizabeth – the daughter of his brother, William – who had married William Wood at Hodnet, near Wem, on 11 July 1798.

The following morning, when Inspector Bannister of ‘B’ Division visited the Five Chimneys, he admitted to being ‘quite astonished’ at what he found. Bickerton, he thought, ‘appeared to be dying in a state of mental imbecility […] He frequently called out for Wise [Rice], who volunteered to attend upon him, to get him change for a ten-pound note, and seemed as if in a state of unconsciousness’.32 Shocked at the old man’s plight, Bannister gave instructions that ‘every care should be taken of him’ and immediately hurried away to encourage the parish authorities to assume responsibility for the invalid.

Under the terms of the Poor Relief Act of 1601, administration of relief to the poor fell to two overseers in each parish, those selected being usually churchwardens or local landowners, who worked under the supervision of a magistrate. Unpaid and often appointed against their will, it is not surprising that many overseers proved far from conscientious in the performance of their duties and Bannister’s request for urgent assistance fell on deaf ears.

On reaching the home of the first overseer, he was informed that ‘the case was not in his district’.33 He then proceeded to St Margaret’s parish workhouse on Dean Street, just half a mile or so from his station house in Queen’s Square. Here he found that the overseer was out. Frustrated, Bannister ‘left word that as soon as any overseer arrived to inform him at the station-house close by, as he wished to speak to him’.34 But these instructions were either forgotten or ignored, and no one attended him. Despite these rebuffs, Bannister refused to give up and he applied, next, to one of the three stipendiary magistrates attached to his station house.

At last, in the 43-year-old David Gregorie, a barrister at Lincoln’s Inn who had been appointed as a Westminster magistrate in 1825, he found someone both willing and able to take action. The son of Charles Gregorie, who had made his fortune as a ship’s captain with the East India Company, and the grandson of the Whig historian Catherine Macaulay, David Gregorie was a handsome and wealthy man – wealthy, or reckless enough, indeed, to indulge in the fashionable pastime of high-stakes gambling and to lose £300 in a single night’s play at piquet against one of the best players in England.35 Fortunately, he also had the reputation for being conscientious in the performance of his duties as a magistrate. On hearing Bannister’s statement, Gregorie ‘gave immediate directions to Woodberry, one of the officers of the establishment, to go instantly to the parochial authorities, and inform them of the wretched state of the dying man, and, added the Magistrate, “If they will not remove him to some place of comfort, we must”’. But it was too late.

When a reporter for the Morning Post arrived at the Five Chimneys that afternoon to enquire whether Bickerton had been removed to the workhouse, Charles Rice told him, ‘There is no occasion now, Sir; the poor creature died about an hour ago, there on that blanket on the floor’.36 He went on to say that, about half an hour after Bickerton took his last breath, a cot had arrived from the overseers to convey him to the workhouse infirmary.

If this delay had lasted only from the time of Bannister’s first visit to the workhouse that morning, it might have been forgivable. However, it later transpired that the old man’s plight had been notified to the authorities some days previously, and they had done nothing:

He has been laying in the same dreadful state of imbecility for some days, without a friend or acquaintance to come near him, without any covering, on the bare boards, and had it not been for the interference of some casual passengers, who informed the police of the circumstance, the whole affair would have been hushed up, and the unfortunate deceased would have been sent to the dissecting-room.37

Having learned all the circumstances of Bickerton’s death, Coroner Higgs now called the surgeon who had responded to Mr M’Carthy’s urgent summons of Sunday evening: the 28-year-old Dr John Hastings of 39 Vauxhall Bridge Road.

Senior Physician to the Blenheim Street Free Dispensary and Infirmary and a member of the Royal Medical Society of Edinburgh, the Parisian Medical Society, the Microscopical Society and the Ethnological Society,38 Hastings would later be described by one contemporary as possessing ‘consummate tact, and a pleasing, genial manner’ but only ‘moderate ability and little acquirements’.39 At the time of the inquest, he stood on the threshold of a medical career that, after some initial success, would eventually become mired in accusations of incompetence and quackery, the accusations resulting from his later decision to specialise in, and to publish on, the subject of consumption – a topic about which, in the opinion of his obituarist, he displayed ‘much ignorance’.40 According to the same critic, his medical writings as a whole would meet with ‘the hostility of the entire medical press’, and his advocacy of ‘the excreta of reptiles’ as a failsafe remedy for tuberculosis would lead to his being lambasted both mercilessly and publicly.41 When he decided to sue a mocking critic in The Lancet, Hastings was further humiliated by the Lord Chief Justice, Sir Alexander Cockburn, who declared, ‘it was not to be wondered at that the matter was treated rather sarcastically when the public were told that phthisis could be cured by the dung of snakes’.42

But Hastings’ notoriety lay in the future. In October 1833, he appeared before the inquest as a respectable physician with a growing practice. He told Higgs and the jury that he had known Bickerton for some time and was sufficiently knowledgeable about his health to confirm that ‘For the last five years he had been subject to a disease of the kidneys’.43 He went on to state that, at the time of his visit, he had found his patient:

… in a state of great exhaustion; he was in the arms of death. He was just able to say ‘Let me die quietly’ […] he had seen him beg a crust of bread of a Lady that she was going to throw to a dog. He thought it a piece of extravagance to wear shirts; he would pick up bones or anything in the streets. The deceased was an excellent scholar. Witness was of opinion that if he had been better fed and taken care of he might have lived ten years longer.44

In the absence of a post-mortem report, we must assume that the doctor relied on his previous knowledge of the dead man in order to make such an extraordinarily bold statement regarding the life expectancy of a 78-year-old suffering from kidney disease.

Whatever the value of Hastings’ predictions, there was little or no chance of establishing the precise cause of Bickerton’s death as post-mortems remained exceptionally rare. In 1842, for instance, one of Westminster’s coroners held over 300 inquests, but summoned a physician to give evidence on only eighteen occasions and ordered just four post-mortems. As one modern commentator has remarked, ‘Coroners often simply guessed at the causes of death at many of their inquests. If there were no witnesses, no obvious signs of violence, and no obvious suspects, if the victims were poor, unknown, unimportant, why bother with an extensive and expensive investigation?’45 Nonetheless, Hastings’ opinion must have made uncomfortable reading for the workhouse overseers who, by implication at least, had already been accused of neglect and indifference.

The last witness, Daniel Friend of 4 Bleeding Hart Yard, Hatton Garden, was able to add a little more regarding Bickerton’s background, character and habits. According to his evidence, the old man had been ‘complete master’ of five or six languages, including Hebrew. He had previously kept a school among the dilapidated Elizabethan townhouses on Wych Street, off the Strand, and approximately six years prior to his death he had purchased the freehold of the Five Chimneys for £380; he also owned one or two houses on nearby Edward Street.

Friend also stated that, some time ago, Bickerton had seized upon a Mr Dance, a broker, who had inhabited one of these properties, claiming arrears in rent. Dance had then countersued, with the result that Bickerton had been thrown into Whitecross Street Debtors’ Prison in Islington – a prison with a particularly bad reputation since its inmates occupied common wards rather than individual rooms, meaning that ‘the well-disposed debtor when so inclined, had no means of protecting himself from association with the depraved’.46 Friend had last seen Bickerton the previous Friday:

He was then knocking up some old tin saucepans, and picking the wire out to sell for old iron. He went out with the wire, and brought home a salt herring and a pound of potatoes. He also brought a bottle, containing some vitriol and water, which he took for his complaint.** He always complained of being ill-used by Mr Dance.47

Having heard testimony from all the available witnesses, the jury now asked that they be permitted to examine the documents given by Bickerton to Charles Rice. These papers, which a fastidious reporter from The Times described as being in a ‘dirty state’,48 consisted of an agreement between Bickerton and a Mr Nightingale for the sale of the Five Chimneys for the sum of £400, and a small bundle of letters, one each from the Duke of Portland and the Earl of Liverpool, and a third, addressed by one William James to David Gregorie, the magistrate. All proved highly interesting.

The one from the Duke of Portland, dated 28 May 1808, confirmed the availability of an unspecified position for Bickerton in Oxford – thereby appearing to prove that Bickerton did, indeed, possess some scholarly attainments. The second, from Robert Banks Jenkinson, the 2nd Earl of Liverpool, apologised for a tardy reply to Bickerton’s correspondence before going on to invite him to an audience at his London home, Fife House, on 29 or 31 August 1818. What made these letters extraordinary was that, at the time they set pen to paper, both writers had been serving as prime minister. What, the jurors might ask, could these men, at the pinnacle of their fame and power, have to do with the miserly – and potentially insane – resident of the Five Chimneys?

However, in the context of recent events, it was the third letter that proved of greatest significance. In it, William James – a man of unknown rank and profession – recommended that David Gregorie, the magistrate, investigate Bickerton’s claims against Mr Dance who, he asserted, had ‘got possession of all his writings relative to his property, of the value of seven or eight hundred pounds, and that Mr Bickerton was in a state of starvation’.49 This correspondence revealed that, while Gregorie had immediately swung into action when approached by Inspector Bannister on Monday, 7 October, the case had been brought to his attention long before and, seemingly, he had done nothing: a further damning indictment of the failings in the administration of poor relief in the Borough of Westminster. Moreover, it suggested that Bickerton’s penury might have resulted from a fraudulent act on the part of Dance; if so, a proper investigation on the part of Gregorie could have resulted in an alleviation of the dead man’s predicament.

At this point in the evening, proceedings were interrupted when Inspector Bannister asked to approach the bench. Having been granted permission, he informed the coroner that ‘there was a very respectable Gentleman below who claimed kindred with the deceased, and wished to bury him in a respectable manner, but he did not appear willing to give evidence’.50 Upon the jury’s request for an opportunity to examine this interested party, his objections were overruled by the coroner who ordered him to appear before the inquest.

The ‘very respectable Gentleman’ proved to be Richard Palin Bickerton of 4 Adelaide Street, the Strand, a Licentiate of the Society of Apothecaries, a Member of the Royal College of Surgeons and surgeon to the St John’s Wood and Portland Town Provident Dispensary.51 Having taken the stand, Dr Bickerton proceeded to tell the inquest that the dead man was:

… his nearest relative. He had not seen him for many years, nor should he have known of his death had he not read a paragraph in the papers of that day.

Juror – What relation are you to the deceased?

Witness – He was brother to my grandfather, and I claim his property.

Juror – It is stated in the papers that he is supposed to have a brother very wealthy in the City – is that so?

Witness – That is not the case; if he has any brothers they must be in Herefordshire.

Juror – What was his father?

Witness – He was a farmer. The deceased studied at Oxford, and was brought up for the Church.52

According to a report published in the Examiner, the doctor then stated that ‘he was willing to be at the expense of the funeral, on condition that he was reimbursed, if he failed of establishing his relationship’.53 The coroner responded tersely, observing that he ‘could say nothing on that subject’.

With no further witnesses to call and no more evidence to examine, the moment had come for the jury to assimilate the information presented to them, to deliberate and, with Higgs’ guidance, to reach a verdict in this curious case.

________

* Geoffrey (1152–1212) was the illegitimate son of King Henry II and therefore half-brother to Richard I and King John, and uncle to Henry III. He served as Chancellor to Henry II as well as being Archbishop of York. Simon of Apulia (died 1223) was created Dean of York in 1194 after a lengthy election dispute resulting from Geoffrey’s desire to appoint instead his brother, Peter. A further argument erupted when Simon refused to resign his position as Chancellor of the Cathedral. Perhaps Ralph of Wigtoft’s attempt to assassinate Simon was a consequence of these disputes. It is unknown whether he acted with the sanction of his master, though it is worth remembering that Geoffrey’s father, Henry II, had himself dealt in summary fashion with another turbulent priest, Thomas Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury.

** Bickerton may have been using cupric sulphate, or blue vitriol, as an emetic.