Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Ediciones Históricas

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Serie: Brief

- Sprache: Englisch

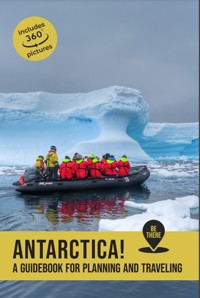

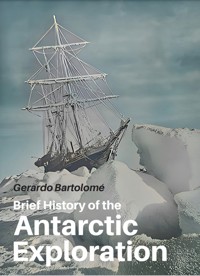

Antarctica, a continent like no other. Not only because of its beauty but also because of its unique history, without wars, kings or indigenous cultures. This book delves into its exploration, offering key insights into events and motivations. A concise overview, it's designed for those preparing for an Antarctic journey or seeking quick insights into its history. With over 150 images, it captures the essence of this exceptional place. For more in-depth explorations, additional resources are suggested in the final appendix. Explore Antarctica's history through a succinct and enjoyable reading experience.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Gerardo Bartolomé

Brief History of the

Antarctic Exploration

Gerardo, Bartolomé

Brief history of the Antarctic Exploration / Bartolomé Gerardo. - 1a ed. - Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires: Ediciones Históricas, 2024.

Libro digital, EPUB

Archivo Digital: descarga y online

ISBN 978-631-90350-4-9

1. Exploración Geográfica. I. Título.

CDD 998

© 2024 GERARDO BARTOLOMÉ ISBN 978-631-90350-4-9

Published by Ediciones Históricas / Gerardo M. Bartolomé, established in Buenos Aires, Argentina. For more information write to [email protected] or [email protected]

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which this is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means without the prior written permission of the copyright owner of this book.

Cover by Ediciones Históricas.

Book design by Ricardo A. Dorr.

INDEX

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER 1. History of a Geological Odyssey

CHAPTER 2. Placing Antarctica on the Map

CHAPTER 3. Early Expeditions

CHAPTER 4. The Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration

CHAPTER 5. The Belgian Antarctic Expedition Commonly Known as the Belgica Expedition (1897-1899)

CHAPTER 6. The British National Antarctic Expedition also called Scott’s Discovery Expedition (1901-1904)

CHAPTER 7. The Swedish Antarctic Expedition Led by Otto Nordenskjöld (1901-1904)

CHAPTER 8. Charcot’s French Antarctic Expedition (1903-1905)

CHAPTER 9. British Imperial Antarctic Expedition also called the Nimrod Expedition, by Ernest Shackleton (1907-1909)

CHAPTER 10. News from the North

CHAPTER 11. Race to the South Pole, First Season

CHAPTER 12. Race to the South Pole, Second Season

CHAPTER 13. Tragedy

CHAPTER 14. Shackleton’s Imperial TransAntarctic Expedition

CHAPTER 15. Shackleton’s Last Expedition

CHAPTER 16. A New Look at Antarctica

CHAPTER 17. The Antarctic Treaty

CHAPTER 18. Dogs in Antarctica

Recommendations

About the author

Other titles by Gerardo Bartolomé

INTRODUCTION

Antarctica stands as a continent like no other, both in its stark physical appearance and its unparalleled history. Devoid of wars, monarchs, religions, and indigenous cultures, the narrative of Antarctica unfolds primarily through the lens of exploration. Remarkably, its present reality is equally distinctive—a collaborative effort among various nations, even those with historical rivalries, to preserve the pristine nature of this white expanse.

This book delves into the exploration of Antarctica, aiming to unravel the events and motivations that shaped its unique history. Rather than an exhaustive catalog of details and anecdotes, the focus is on providing a comprehensive understanding of key events. Whether the reader is preparing for a journey to Antarctica or simply seeking a quick yet insightful overview of its history, this publication offers a concise and enjoyable reading experience. For those desiring more in-depth explorations of specific events, additional resources are suggested in the final appendix.

Comprising over 150 images, this publication recognizes the exceptional nature of Antarctica and the events that happened there. Many of these visuals were captured by the very expeditioners who embarked on these journeys, emphasizing the intrinsic role of photography as a means to comprehend the uniqueness of this icy realm.

Gerardo Bartolomé

Endurance photographed during the Antarctic night by Frank Hurley

CHAPTER 1. History of a Geological Odyssey

Antarctica remained uninhabited by humans until the advent of civilization and exploration. It stands as a singular continent, distinguished by vast expanses of ice that differentiate it from all others. Life on this icy mass is notably distinct, with an environment less vibrant than many other regions of the world. This uniqueness stems from its extraordinary position over the South Pole, where the angled rays of sun-light barely succeed in raising temperatures beyond freezing points. Nevertheless, Antarctica’s present icy landscape signifies a relatively recent transformation, as it did not always exhibit such extreme conditions.

Forests in the Antarctic Peninsula 70-100 million years ago.

Artistic reconstruction by J. Howe, J. E. Francis and others

Pangea continent

The concept of Continental Drift is fundamental to understanding the geological history of Earth and the distribution of continents. Around 200 million years ago, Earth’s landmasses were part of a supercontinent known as Pangea. Pangea began breaking apart due to the process of continental drift, driven by the movement of tectonic plates. One of the resulting fragments was Gondwana, which included what are now the continents of South America, Africa, Antarctica, Australia, the Indian subcontinent, and the Arabian Peninsula.

As Gondwana continued to break apart, these landmasses drifted towards their current positions. The process of continental drift significantly influenced Earth’s climate, ecology, and the distribution of flora and fauna. The displacement of continents gave rise to new oceanic currents, resulting in alterations to global weather patterns and the facilitation of the evolution of diverse ecosystems.

Over the course of millions of years, the land that eventually became Antarctica gradually shifted southward, undergoing substantial climate changes. Originally situated nearer to the equator within the supercontinent Gondwana, Antarctica enjoyed a temperate climate and was adorned with lush forests. However, as it journeyed towards the South Pole, a profound transformation ensued. Approximately 35 million years ago, Antarctica found itself isolated at the South Pole, resulting in a cooling climate and, eventually, the formation of an extensive ice sheet that covered the entire continent.

Wegener used fossil record to deduce his Continental Drift Theory

This transition had profound consequences for the flora and fauna residing in Antarctica. The landscape, once adorned with forests, yielded to a vast expanse of ice, leading to significant adaptations and, in some cases, the disappearance of many species. The fossil record in Antarctica serves as a valuable archive, offering insights into the evolution and adaptation of life in response to the impactful environmental changes induced by continental drift and the subsequent glaciation of the continent. The study of these ancient ecosystems is instrumental in assisting scientists in unraveling the intricate interplay between geological processes and the evolution of life on Earth.

World-map including Antarctica

CHAPTER 2. Placing Antarctica on the Map

The term ‘Arctic’ traces its roots to ancient Greek, stemming from the word ‘arktikos,’ which translates to ‘of the bear’ or ‘northern.’ This designation specifically refers to the constellation Ursa Major, widely recognized as the Great Bear, prominently visible in the northern sky. While Ursa Major does not contain Polaris, the North Star, Polaris is associated with its neighboring constellation Ursa Minor.

The Arctic region derives its name from its celestial connection to the northernmost part of the Earth. The term “Arctic” is rooted in the Greek word “arktikos,” associated with the northern celestial bear, a connection that significantly influenced the nomenclature of the Arctic region. This term has persisted for centuries, serving as a fundamental descriptor for Earth’s northern extremities. In contrast, the Antarctic, derived from the Greek word “antarktikos,” meaning “opposite to the Arctic” or “opposite to the bear,” underscores its location at the opposite pole of the Earth, establishing a clear counterpart to the Arctic.

Polaris in Ursa Minor and Ursa Major

A Mysterious map…

In 1572, Abraham Ortelius released a map titled “Typus Orbis Terrarum,” a notable inclusion within his comprehensive atlas named “Theatrum Orbis Terrarum.” This map featured a substantial landmass situated in the South Pole region, identified as “Terra Australis,” translating to the “land of the South” in Latin.

Was he aware of the existence of Antarctica? No. His reasoning followed the belief that, given the Earth’s spherical nature, there must be a balance of land in both hemispheres.

Abraham Ortelius, by Peter Paul Rubens

Ortelius’ World Map

If there was already extensive known land in the northern hemisphere, he inferred that undiscovered land must exist in the southern hemisphere. Drawing on Magellan’s successful crossing from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean, he speculated that the straits, now recognized as the Straits of Magellan, separated America from the presumed Terra Australis.

The term Antarticus was similarly employed as a counterpart to Arcticus.

As explorers ventured south, Terra Australis/Antarcticus gradually diminished in size due to the absence of such a landmass. In 1580, Sir Francis Drake sailed south of Tierra del Fuego without encountering a continent. However, in 1606, Willem Janszoon successfully discovered land in the southern region, unveiling Terra Australis as a distinct continent.

In 1770, Captain James Cook explored the southern reaches of Terra Australis, later named Australia, and determined that it was surrounded by water. This discovery indicated that Australia did not extend all the way to the South Pole.

Captain James Cook

Captain Cook made another remarkable discovery when he observed floating icebergs south of Tierra del Fuego. Notably, these icebergs carried rocks and dust, indicating that they were not formed from frozen sea-ice but rather originated on land, likely from glaciers. This revelation suggested the presence of land to the south and marked the first tangible evidence of the existence of Antarcticus. With this newfound information, it became clear that Australia and Antarctica were distinct continents.

For nearly fifty years, Antarctica remained relatively unexplored. However, after the Napoleonic Wars, a renewed interest in exploration emerged. Magnetism played a crucial role in mapmaking during this period. Navigators relied on compasses, which pointed to the magnetic North and South poles rather than the geographic ones. Therefore, determining the precise locations of the magnetic poles was essential for ensuring accurate compass readings and enabling the determination of true geographic directions.

Map of Antarctica by Gis Geography

CHAPTER 3. Early Expeditions

In 1820, three separate expeditions ventured independently southward, providing confirmation of the existence of Antarctica, famously known as the White Continent. The explorers were Gottlieb von Bellinghausen (from Russia), Edward Bransfield (UK), and Nathaniel Palmer (USA). Their observations revealed towering mountains and expanses of ice, yet landing on the continent proved exceedingly perilous, deterring direct exploration.

While there remains some uncertainty about which expedition was the first to truly sight the continent, it is generally acknowledged that Gottlieb Bellinghausen is credited with this achievement.

Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen

Whalers and sealers extended their voyages progressively southward, driven by economic interests. In pursuit of the lucrative fur seals, many thousands were hunted and killed in Patagonia and the southern islands, leading to a rapid decline in their population. By 1820, the fur seals in South America and Southern Atlantic Islands were nearly extinct due to intensive hunting.

In 1821, upon hearing that ice-covered islands in the extreme South were teeming with fur seals, numerous sealers set sail to what is now known as the South Shetlands. There, they conducted extensive and indiscriminate slaughtering, depleting the population of fur seals. As a consequence, each subsequent year necessitated sailing further south, as the once-populated beaches became desolate after a single sealing season.

Nathaniel Palmer

This pattern continued with sealers discovering other islands rich in fur seals, only to find the populations depleted within a short time. Eventually, the fur seals were exhausted, and sealers were unable to venture further south due to the hazardous navigation among icebergs in their sail ships.

While most sealers maintained secrecy about their discoveries to avoid informing competitors, there was an exception in the form of the British navigator James Weddell. Simultaneous with his documentation and exploration, numerous fur seals were ruthlessly hunted, totaling in the hundreds or even thousands. Several years later, Weddell published an account of his explorations spanning from 1821 to 1824. As a lasting tribute to his contributions, the region of Antarctica explored by Weddell now bears his name.

James Weddell

In the years 1839-1843, shortly after the return of HMS Beagle to the UK with Charles Darwin onboard, Great Britain commissioned an expedition led by James Ross to explore Antarctica. Equipped with two ships, Erebus and Terror, Ross extensively surveyed the coastline of the continent. During his exploration, he identified an active volcano, which he aptly named after HMS Erebus