Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

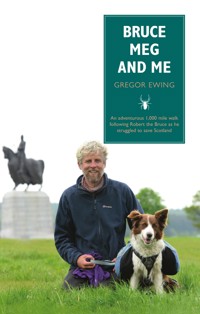

Craving an escape from everyday life, Gregor Ewing writes a personal account of his 1,000 mile walk over nine weeks with collie Meg that takes them through Northern Ireland and the central belt of Scotland, literally following in Robert the Bruce's footsteps. From Kintyre, Arran and Ardrossan north to Ayr through Glasgow to Fort William and Elgin, south to Inverurie, Aberdeen and Dundee, over the Forth to Edinburgh and Berwick upon Tweed then east through Roxburghshire to Bannockburn, Gregor frames his expedition with historical background that follows Robert the Bruce's journey to start a campaign which led to his famous victory seven years later.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 344

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

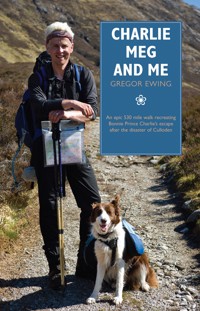

GREGOR EWINGhas a passion for the outdoors that is only matched by his interest in history. His first book,Charlie, Meg and Me, recounts his500Mile walk in2012– accompanied by border collie, Meg – following the route of Bonnie Prince Charlie’s flight after the Battle of Culloden. In2014, he walked over1,000miles in a continuous journey following in the footsteps of Robert the Bruce.Bruce, Meg and Meis the story of the expedition. Gregor has given talks at literary, history and outdoor festivals throughout Scotland and has spoken at events organised by the National Library of Scotland and Culloden Battlefield Centre. He lives in Falkirk with his wife, Nicola, and three daughters, Sophie, Kara and Abbie. The dogs, Meg and Ailsa, complete the female entourage in his household.

Bruce, Meg and Me

An adventurous 1,000 mile walk following Robert the Bruce as he struggled to save Scotland

GREGOR EWING

LuathPress Limited

Edinburgh

www.luath.co.uk

First published2015

ISBN: (EBK) 978-1-910324-60-8

(BK) 978-1-910021-80-4

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book

under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act1988has been asserted.

Maps © Gregor Ewing. Base map information supplied

by Open Street & Cycle maps (and) contributors

(www.openstreetmap.org) and reproduced under the

Creative Commons Licence.

© Gregor Ewing2015

Contents

List of Maps

Acknowledgements

Foreword by Tony Pollard

Introduction

Historical Prologue

CHAPTER 1: The Trossachs and Arran

CHAPTER 2: Turnberry and the Galloway Hills

CHAPTER 3: Heading North

CHAPTER 4: Argyll

CHAPTER 5: The Great Glen

CHAPTER 6: The Garioch, Buchan and Aberdeen

CHAPTER 7: Deeside to Forfar

CHAPTER 8: The Fife Coastal Path

CHAPTER 9: Lothian

CHAPTER 10: Homeward Bound

Timeline

References

Bibliography

List of Maps

The Complete Journey

Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park

From the Isle of Arran to Turnberry

Entering the Galloway Hills

Adventures in the Galloway Hills

Loch Doon to Loudon Hill

Loudon Hill to Glasgow

The West Highland Way

Argyll

Glen Etive to Fort William

The Great Glen Way

Loch Ness and the Beauly Firth

Inverness to Auldearn

Moray

Huntly to Ellon

Aberdeen and the Deeside Way

Aboyne to Forfar

Forfar to Fife

The Fife Coastal Path

Lothian

Dunbar to Dowlaw Farm

The Berwickshire Coastal Path

The Scottish Borders

Cross-Borders Drove Road

West Linton to Linlithgow

The Road to Bannockburn

The Complete Journey

To Nicola, Sophie, Kara and Abbie

Acknowledgements

It was only through the support of my wife Nicola that I was able to undertake my journey. A loving thanks to her for keeping the home fires burning.

Friends who met or accompanied on the way gave me great encouragement and helped keep me sane. Especially, George, Jennifer, Graeme and Iain.

Thanks to Andy Smith, Ian Scott and Jennie Renton at Luath who all helped turn my manuscript into the book in front of you today.

Once again I am grateful to Dr Tony Pollard, for finding time in his busy schedule to write a thoughtful and amusing foreword.

Foreword

SAY THE NAME Robert the Bruce and the next word that comes to mind is very likely Bannockburn. And even now, after years of studying the Scottish Wars of Independence and visiting their many battlefields it is still Bannockburn that I most strongly associate with him, despite the fact that his life story, and his military experience, consisted of so much more. I can perhaps be forgiven for this single-mindedness though, as the Battle of Bannockburn has probably taken up more of my time as a battlefield archaeologist than any other, from my first failure to find evidence for the battle site while making the television seriesTwo Men in a Trenchback in 2003, to finally being able to say with confidence where it was fought after an ambitious project in 2013–14.

It was the 700Th anniversary of the Battle of Bannockburn in 2014 that really brought Robert the Bruce alive for many people and it was certainly the motivation for that successful project and the associated BBC TV programmes,The Quest for Bannockburn,presented by my old friend Neil Oliver and myself. One of the great pleasures of that project was the involvement of locals and school children in the quest; it was a real community undertaking, in which well over 1,000 volunteers took part. There were also other events to mark the occasion, which just happened to coincide closely with the Referendum for Scottish Independence (which failed to emulate Bruce’s achievements), such as the opening of the new state-of-the-art visitor centre and the re-enactment of the battle at theBannockburn Liveweekend organised by the National Trust for Scotland.

But away from the crowds and the TV screens, a more personal and far more demanding tribute to the great man was taking place. Over the best part of two months in early 2014, Gregor Ewing and his faithful dog, Meg, undertook an epic walk of 1,000 miles as they followed the route of Robert the Bruce’s movements through Scotland prior to the Battle of Bannockburn in June 1314. This was not the first time they had hiked back into history, in 2012 the pair followed the trail of Bonnie Prince Charlie from his defeat at Culloden in April 1746 to his rescue by a French ship off the west coast of Scotland the following August (a mere 530-mile stroll).

The idea of discovering and communicating history through the medium of a journey has always appealed to me. As a schoolboy, I hatched a scheme to follow the 1,170 mile route taken by the Nez Percé Indians under Chief Joseph from their reservation to freedom in Canada in 1877, all the way pursued by the US Army. Despite putting up some impressive fights they didn’t make it. My plan, which I spent many an hour pondering, was to follow the route on the back of one of the Appaloosa ponies for which the tribe were well known. But alas, a daydream it remained. What’s so impressive about Gregor is that he turns his daydreams into reality.

Back in 2014, while I roamed the carse fields adjacent to the banks of the Bannockburn, monitoring the progress of metal-detecting teams or keeping an eye on our volunteer archaeologists, so Gregor and Meg progressed from one corner of the country to the next, moving from one Bruce milestone to another. But as he documents here, at one point prior to setting out on his expedition he found time to take part in that project, digging one of our many test pits and to his delight finding a sherd of medieval pottery in it.

The journey has long been a metaphor for the human experience, albeit one that has recently strayed into saccharin cliché when it comes to the sort of challenges pursued on TV talent shows and dance competitions. In this book, however, Gregor reminds us that some of the most important periods of our history are made up of journeys, with momentous events such as powerful marriages, coronations and battles punctuating voyages, marches and expeditions, which in the days before motorised transport required considerable amounts of determination and stamina, and as Gregor found out, a hefty chunk of time.

Bruce was determined to be king of Scotland, to be the winner of what became known as the Great Cause, even if it meant committing murder, seeing his family almost wiped out, waging war and laying waste to large tracts of his own country. Travelling around the kingdom was an essential part of that process. In the days before mass communication it was essential that a monarch was seen by his people (seeing is after all believing), and Bruce was a graduate of the ‘if you want something done well, do it yourself’ school. It is said that even the appearance of an unwell Bruce, who at that point was carried on a litter, was enough to send his enemies fleeing the field at Inverurie in 1308. In any case, his army was never really big enough to send men off on one campaign while he fought another – an exception was the Irish campaign of 1315–18 and that ended in disaster (see below). So it was that he spent much of his life marching from one place to another, exterminating his enemies, impressing his allies and awing his people.

Winning the crown was hard work, and even though victory at Bannockburn was to establish him as king in Scotland, there was a long way to go before England would accept the independence of their northern neighbour (the Scottish Wars of Independence did not come to an end until 1355). It’s a fact that even now, after the 700Th anniversary, many people don’t realise that Bannockburn did not end the story, but as Gregor’s book so ably demonstrates, there was also lot going in Bruce’s life before the most famous battle in Scotland’s history was fought.

Gregor has provided an entertaining account of a journey made by man and dog, which also weaves in the story of key incidents in Bruce’s life as he made his own progressions around Scotland over 700 years ago. Away from Bannockburn my work, in this case on the compilation of Historic Scotland’s Inventory of Historic Battlefields, has taken me to the sites of other key battles fought by Bruce, including the Methven, Loudon Hill and Inverurie. I have even followed the trail, by car I hasten to add, of his brother’s ill-fated campaign in Ireland, which took place between 1315 and 1318 and ended with Edward Bruce’s death at the Battle of Foughart. As a demonstration that seeing was believing it is not too much of a digression to point out that Edward’s head was sent to Edward II and his limbs dispatched to all the corners of Ireland, all to prove that he was in fact dead. This series of special deliveries also demonstrates that death need not be a barrier to travel back in Bruce’s day.

Despite my own encounters with the landscapes of Robert Bruce, I am not ashamed to admit that there are battlefields that Gregor and Meg visited which I have not. These include Glen Trool, where Bruce demonstrated a talent for Guerrilla warfare when he ambushed a larger mounted English force. There are also in these pages a number of stories I had not come across before, and as a battlefield archaeologist found most tantalising. One of these relates to farmers digging up weapons from their fields before Clatteringshaws Loch was created as a reservoir. I was also as surprised as Gregor to learn that St Conan’s Kirk on the banks of Loch Awe contains one of Bruce’s toe bones. I have driven past that church on numerous occasions, and if I had known would definitely have stopped off to pay my respects.

I cannot end without making a small confession. It was not difficult to say yes to penning this Foreword to the book when Gregor invited me to do so, way back before he had started his journey. I was interested in the subject matter and confident it would be good, as he had more than proven his abilities as an engaging writer withCharlie, Meg and Me, for which I had been pleased to provide the same service (though back then he was an unknown quantity). Good intentions are not the same as fulfilled promises, though, and so it was that I found myself buried in other writing tasks when Gregor very politely asked via email whether I had read the manuscript and therefore made any progress with the foreword; he did after all have a publication schedule. To my shame I had not even begun to read it, despite it being in my possession for some time by then, such had been the distraction of my other projects. Ah well, I thought, it’s Friday and I’ll give it a quick skim-read before dashing something off and getting back to him on Monday. I am being so candid here because the best recommendation I can make for this book is that my intention to read a section here and a section there, just enough to allow me to fulfil my promise, came to nought as it proved to be such a page turner that I didn’t put it down before having read it from cover to cover.

Where will Gregor’s next epic walk take him? Well, at one point in these pages he makes a passing remark about wanting to drive cattle along ancient drove roads from the Western Isles to the cattle market at Falkirk. It just so happens that I spent some time living next to an old drove road near Oban as a child and the idea of driving cattle over a long distance has always appealed. After all, what self-respecting man of my age didn’t want to be a cowboy in his callow youth? I suspect also that, if relieved of her backpack, Meg would make a splendid cattle dog. Accordingly, I have told Greg that no such undertaking is to be made without me. It might, however, be some time before you seeTony, Meg, the Coos and Me, on the shelves of your local bookshop.

Tony Pollard,

Glasgow, March 2015

Introduction

IN 2012, I fulfilled a long held desire to escape to the hills. In a continuous journey, I walked over 850Km (530 miles), following the route of Bonnie Prince Charlie’s escape after the disastrous Battle of Culloden in 1746. Carrying my own food, shelter and equipment, and with just my border collie, Meg, for company I retraced the Prince’s route through the Highlands and Islands of northwest Scotland. Returning to the comforts of home, I wrote up my adventures, and was delighted to getCharlie, Meg and Mepublished. I did a short promotional book tour and was regularly asked, ‘What’s your next escapade?’

Following Bonnie Prince Charlie’s escape had been one of the highlights of my life, which I imagined would be a one-off. But hey, why not? Once the seed was sewn it didn’t take me long to decide to attempt something similar and I realised that with the 700Th anniversary of the Battle of Bannockburn approaching, surely it was a perfect time to follow the struggles of Robert the Bruce. The story was captivating, took in large swathes of Scotland and was of particular personal interest to me: Nigel Tranter’sBruce Trilogyhad been the spark which flamed my lifelong interest in Scotland’s history. Undoubtedly though, the seminal book was GWS Barrow’sRobert Bruce and the Community of the Realm of Scotland, which I consulted to see if it would be feasible to follow in Bruce’s footsteps.

The Battle of Bannockburn, Scotland’s most famous military victory, was masterminded by Robert the Bruce, who went on to restore the country’s status as an independent kingdom in the 14Th century. The story I wanted to tell was that of the early years of Bruce’s kingship, when tearing Scotland back from the clutches of England’s Plantagenet rulers looked beyond the realms of serious possibility.

Within five months of being crowned King of Scots in 1306 by a small band of supporters, Bruce was defeated three times in battle and forced into hiding on the myriad of islands off Scotland’s rugged west coast. The following year, on his return to the mainland at Turnberry, he overcame tremendous adversity to establish his kingship, unite the country and inflict defeat upon a nation, far larger and more powerful, than his own. This transformation of fortunes is what Barrow calls ‘one of the great heroic enterprises of History’.

For my own part, I wanted to push my own boundaries and go further than my previous walk. Seven hundred miles on the 700Th anniversary of Bruce’s great triumph seemed both appropriate and achievable. I also wanted to follow as accurately as I could Bruce’s return to Scotland in 1307 when he began the attempt to win back his crown. This campaign of 1307–08, a civil war, laid the foundations for (although it by no means guaranteed) future success. Thereafter, Robert focused on defeating the occupying forces of Edward II and pressurising him to recognise Scotland as an independent realm. I soon realised that I couldn’t fit all this history into 700 miles (1100Km) and the distance crept up towards 1,000 miles (1,600Km) which my ego embraced before my legs could put in an appeal. I ended up with a route which would allow me to follow Bruce from his lowest ebb to ultimate triumph. The main part of this journey would take me round Scotland in a clockwise direction, starting in Galloway, travelling northward, through Argyll and up the Great Glen to Inverness. After crossing over to the Black Isle, I would return to Moray and Aberdeenshire before continuing south, down the east coast, all the way to the border with England and the town of Berwick upon Tweed. Turning around I would march back through the hills to the Forth Valley and Bannockburn. Following the King’s route wherever possible, and when this was unknown, Scotland’s Great Trails (West Highland Way, Great Glen Way, etc) would be tramped upon between the historic locations.

Accompanied by my dog, Meg, we would be carrying our own food and equipment. I aimed to cover about 30Km (19 miles) per day and would wild camp most evenings – only occasionally would I take advantage of the facilities of a campsite.

Over the course of 12 months I researched the history in detail in order to get to know the story intimately. I wanted to arrive at a castle, monument or battlefield knowing the background. There wouldn’t be time to learn the story as I went, but I hoped to add to my knowledge at each place I visited. Poring over my collection of maps was enjoyable as I sought to find a suitable and accurate route that would keep me in the countryside as much as possible. In between my day job, the research, and the planning, I went running four times a week to build up my fitness once more – the physical prowess gained from my previous walk had been lost completely when I gave up all exercise to concentrate on writing my first book. During that time, too often did I find myself during blank moments staring into the fridge seeking inspiration. For a whole year Meg had been dozing under the kitchen table dreaming of her previous adventures – walking round the block just wasn’t the same anymore. I was excited for her as well as for myself as the day drew near.

Considering my three school-age kids and a very understanding wife would have to cope without me for a lengthy period of absence, it behoved me to make this a worthwhile journey. I was determined to uncover something new about the legendary Bruce, to help justify my, let’s face it, selfish retreat from the responsibilities of everyday life. With my bag packed, my body in half-decent shape and my route planned out in detail, I was ready for the off. Then I got a phone call!

Gregor Ewing,

Falkirk, May 2015

Historical Prologue

THE SCOTTISH WARS of Independence and the subsequent rise of Robert the Bruce came about after King Alexander III of Scotland died in 1286, leaving only an infant in distant Norway as heir to the throne. Scotland and England had evolved from the Dark Ages into the medieval period as separate realms, the last two on an island that once held many small kingdoms. There had been peace between the two countries for 30 years, during which time Scotland had flourished: Alexander’s reign was looked back on by later chroniclers as a golden period in Scotland’s story.

The Maid of Norway, as the child became known, died en route to Scotland, and in order to prevent a bloody civil war, King Edward, a respected neighbour, was asked by the Scots nobility and clergy to choose a new king for their country. A number of claimants came forward, including a certain Robert Bruce, grandfather of the future King Robert I. However, Edward deemed Robert Bruce’s claim to be inferior to that of John Balliol, who was duly selected as King of Scots in 1292.

In accepting the crown, John Balliol paid homage to Edward I as his feudal superior, making the Scottish King subordinate to his English counterpart. This situation lasted for four years, with Edward making increasing demands upon John until eventually the Scottish King rebelled, culminating in the Battle of Dunbar in 1296. The Scottish army was defeated; John was stripped of his crown (as well as the embroidered lions off his coat) and sent to the Tower of London.

Edward decided to rule Scotland directly – royal castles were garrisoned, sheriffs appointed to collect taxes and justiciars to administer English law in Scotland. Armed revolt was almost immediate and after defeating an English army at the Battle of Stirling Bridge in 1297, William Wallace was appointed Guardian of Scotland, acting in the name of the imprisoned King John.

Wallace’s army was defeated at Falkirk the following year and he resigned from the position. Other guardians followed, including John Comyn and Robert the Bruce himself. The Scots maintained a spirited resistance to Edward but by 1305 their defeat was complete. The people’s patriot William Wallace was dead, and virtually all Scotsmen of senior rank had submitted to Edward. Scotland was incorporated within the land of England and would be ruled by a council appointed by the English King.

Then in February 1306, a crime was committed which even in such brutal and turbulent times must have caused shock waves. Robert the Bruce, whose family were strong contenders for the vacant throne in 1286, claimed the crown of Scotland for himself in the most dramatic fashion. He stabbed John Comyn, his main rival for the resumption of a Scottish kingship, in front of the high altar and within the sanctuary of Greyfriars Church in Dumfries, a shocking crime in the most sacred of places.

Within a few weeks, Bruce was crowned King of Scots at Scone in as authentic a ceremony as was possible given the short timespan. The Scottish Church forgave Bruce’s crime for the sake of the nation and supported him. Amongst the attendees at the coronation were three bishops and four earls, the most senior magnates in the country.

Edward I was incensed by Bruce’s uprising. Despite being known as ‘Hammer of the Scots’ after his death, Edward found in life that the nails just kept popping out. A special lieutenant, Aymer de Valence, was despatched to Scotland, backed by an army holding aloft the dreaded dragon banner signalling that the rules by which warfare was conducted were suspended: there would be no mercy for anyone connected with Bruce’s rising.

Robert’s attempt to establish authority and control in Scotland was ended swiftly when he was comprehensively defeated at Methven, near Perth, in June 1306. Aymer de Valence sent his forces out on a night attack and caught Bruce’s army by surprise. The King himself only just escaped; other prominent supporters were caught and executed. In the surviving sources, there are faint details of a second encounter on the banks of Loch Tay as the remnants of Bruce’s army were pursued by the victors.1

The new king remained at large, but he was ambushed along with his last remaining forces at Strath Fillan by a force of Highlanders under the command of John MacDougall, loyal to the Comyn family and now in allegiance with Edward I.

Loch Lomond and the Trossachs Nationak Park.

CHAPTER 1

The Trossachs and Arran

FROM THE OUTSET, I had planned to begin my journey on Rathlin Island, just off the coast of Northern Ireland. After his defeat at Dalrigh, the King was forced to flee Scotland and he spent some time on this small island during the winter of 1306–07 before returning to begin the attempt to reclaim his kingdom. Rathlin seemed like the perfect place from which to launch my own invasion. In some D-Day-like dream, I had envisaged Meg and myself standing on the prow of a small craft, watching Scotland’s shoreline gradually fill the horizon. Approaching the beach, battered only by the wind and rain, we would jump into the sea and run onto the soft white sand of the Kintyre peninsula. Unfortunately, just a few days before the start of my trip, the captain of the private charter boat I had hired, called to say that upcoming bad weather in the Irish Sea was going to make the sailing impossible. I couldn’t delay the trip as I had various rendezvous planned later in the walk, so I had no option but to cancel this leg of the journey. Instead, I made some hasty plans and headed towards Tyndrum in the Trossachs.

So instead of a dreamy sojourn to a mysterious island, I began my journey at Dalrigh, just to the south of Tyndrum. On a bright, sunny day, this is a beautiful Highland landscape, with mountains, glens and rivers begging exploration. On a dull, wet and windy March morning, with the clouds just above head-height, it was just foreboding. My father-in-law dropped me off. After a short stroll together, a quick cheerio to him was far easier than my parting from home early that morning when everyone was upset, not least my wife as she contemplated nine weeks of juggling her full-time job, looking after the house and ferrying the children around, all on her lonesome.

The idea behind this hastily cobbled-together start to my journey was to follow the escape of King Robert the Bruce after he was defeated in battle for the third time in quick succession. This was a disastrous start to his revival of a kingship that had lain dormant since the forced abdication of King John Balliol ten years earlier. It was July 1306, Bruce had been King of Scots for less than four months, and it looked like his reign was to be the briefest of all Scottish monarchs. After reverses at Methven and Loch Tay, the remnants of his army crossed the River Fillan at Dalrigh where they were ambushed by a force of Highlanders under the command of John MacDougall.

There are no detailed descriptions of the battle, but as I stood by the ford I could easily imagine an army of screaming, leaping clansmen emerging from the mist. Bruce’s ragtag forces, caught unawares, would have been seriously handicapped. They were caught in the midst of an awkward manoeuvre and burdened by the injured as well as by the women and children of the new royal family. MacDougall’s lightly armed Highlanders would have been at a distinct advantage on the rough ground and the mounted men of Bruce’s party would have been unable to deploy properly. An inscribed stone bench, between the river and Dalrigh field, marks the spot where Robert and his followers were ambushed. Retreating, they passed little Lochan nan Arm on the south side of the River Fillan, where the King and his followers discarded some of their weapons. At some point during this retreat, the King split up his party and sent his Queen and other prominent females away under the guidance and protection of his brother Nigel. With just a few men left, Bruce took to the hills to make his escape. The King of Scots was now a powerless fugitive in his own country, his army defeated and many of his supporters captured or slain. Powerful and numerous enemies were bent on destroying him, and he was far from friendly territory where he could find safety.

I started walking in the direction of Bruce’s retreat. Meg trotted beside me, knowing full well something major was beginning, because she had been saddled with a cumbersome rucksack. Local legend informs us that King Robert was forced to fight a running battle southwards and I followed the river down Strath Fillan on the footpath of the West Highland Way, the oldest and best known of Scotland’s Great Trails.2Crossing under the A85 and with the tiniest of diversions I was soon at a natural widening of the river, looking at the Holy Pool of St Fillan. In bygone days, those with mental ailments went for a dip in the healing waters. Had I gone for a swim, then suitably cured I’d have been back in the car with my father-in-law. A 1,000 mile continuous walk! Only a dog for company and 65 nights in a tent in Scotland! Madness!

The River Filan; on the far side, the field of Dalrigh.

The West Highland Way runs through Auchtertyre Farm and then past the scanty remains of a once substantial St Fillan’s Priory. This Augustinian priory was once over 50M in length and it was endowed by Bruce 11 years after his defeat here in 1306. St Fillan himself was an 8Th-century monk who preached in this area. His sacred relics were revered and looked after by the Dewars of the Coigreach – the crozier and bell belonging to St Fillan survive to this day. In 1306, having already received forgiveness for his murder of John Comyn from the dominant Roman Church, Bruce was quite possibly in this area seeking forgiveness from the Celtic Church in the presence of these holy relics. The relics were called into use prior to the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314.

Most walkers tackle the West Highland Way from Milngavie to Fort William, the scenery becoming more dramatic as they head towards the Highlands. I was going against the flow of walkers on this short stretch, and I was determined to make the effort to talk to as many people as possible during my walk, hopefully picking up little bits of advice or local knowledge as well as exercising underused vocal chords. I tried a few introductory lines like ‘Where are you heading?’ or ‘Have you come far?’ but just as ‘Do you come here often?’ never seemed to work for me on the dance floor, I didn’t get much response. Letting Meg do the talking seemed to work better as she immediately gained sympathy for her friendly demeanour and cruel panniers.

Crossing the main road again, the path heads uphill through a dense forestry plantation before descending to Crianlarich at the southern end of Strath Fillan. Passing through this village of converging routes, surrounded on all sides by 1,000M mountains, I followed a disused railway track alongside the A85 before coming to Loch Dochart. On a small island in the centre of the loch, partially hidden by trees, was a 16Th-century castle. Unfortunately, 19Th-century repairs made the ruins resemble an industrial chimney and spoiled the scene.

Under the shadow of Ben More, the conical shape of which is so recognisable from Scotland’s Central Belt and which issues a magnetic charm to many Lowland walkers, I followed a track past a farm at the foot of the hill and continued on into Benmore Glen. Getting wetter and colder as I climbed gradually southwards, a sense of impending doom began to creep over me. Reaching a bealach (mountain pass)at a height of 500M, there were snow fields on the slopes above and patches of ice underfoot. A crisis of confidence, mixed with a little bit of guilt, engulfed me. Why the hell was I doing this? What was I thinking about, spending weeks and weeks outdoors again? It had been two years since my previous foray into the hills and I had forgotten how cold, wet and lonely it could be. The rucksack felt bloody heavy as well; I couldn’t imagine day after day with this on my back. How selfish was I, leaving my family behind for over nine weeks to go on some self-fulfilling odyssey?

Trying to banish this negativity from my overactive mind, I tried to latch onto something positive, something to look forward to – but there were no cosy B&B’s on this trip; no meeting with friends or family for a while yet; no little carrots to dangle in front of my mind’s eye.

The Braes of Balquhidder, Loch Doine and, in the distance, Loch Voil.

Plodding on morosely, I reached the summit of the flattened, boulder-strewn pass separating the misty mountains of Stob Binnein and Cruach Ardrain. Descending south by the tumbling white waters of the Inverlochlarig Burn, which was bulging with snow melt, a track appeared and took me down to the Glen of Balquhidder, where Bruce is reputed to have retreated to after the battle.3Still feeling low, I took advantage of a dry spell to stop for an early dinner and took shelter within a little piece of community woodland which gave me some protection from the bitterly cold wind. Dried pasta and instant custard was certainly no gourmet meal, but I devoured it. Thereafter, with a full belly and a mug of scorching hot black coffee in hand, my spirits were fortified.

Heading east along the glen, I reached the smaller of two lochs beautifully set in a narrow valley overlooked by steep-sided hills – the Braes of Balquhidder. Loch Doine connects with Loch Voil, at the head of which was my destination, ‘Bruce’s Stone’, where Robert is said to have rested, having finally having fought off the last of the pursuers from the battle. It must have been a long chase; I had walked 26Km to get to this point, having fought only my own inner turmoil, and yet I was still shattered.

Bruce’s stone surrounded by the raised waters of Loch Voil.

The large, oblong stone with a Scots pine sprouting forth atop was situated in a small cove and surrounded by dark, lapping waters. The most prominent clans in the area, Fergusons, MacLarens and MacGregors, all claim to have helped Bruce here in the Braes of Balquhidder and led him to a cave in the nearby cliffs, where he took shelter for the night.4As I was walking along the road by the lochside, a Land Rover pulled up and the driver offered me a lift. I sought, instead, help in finding this shelter. Having spent his childhood in the glen, the fella knew of the cave I was looking for, but warned it was hard to find – and that it was more of a rock overhang than a cave, over which water poured during wet spells. Disheartened, I trudged up the hillside in the gathering dusk, lacking any belief that I could find this place – anyway, I told myself, it sounded like a rotten place to spend the night. A decision on whether or not to sleep in the cave wasn’t needed, because in the woods at the foot of the brae I lost a walking pole which had been slipped through a belt loop on my trousers. When I eventually noticed its disappearance, my weakened mental state gave way to self-recrimination – it took 20 minutes of frantic searching before I stumbled upon it, and my efforts brought a momentary surge of delight before fading light gave me a good excuse to stop for the day. Thoroughly exhausted, I pitched my tent almost where I stood: on a slope in the forest, in the rain.

Lying in the tent, squeezed alongside Meg and the bulbous rucksack, I was thoroughly miserable at the thought of what I had let myself in for. I regretted my living-room adventurousness, and the rashness with which I had upped the total length of the walk to 1,000 miles (1,600Km). On top of all that, my hastily arranged start had added another three days’ hard walking, rather than the relaxing sail which should have been my introduction. How was I going to cope in a cramped tent in the rain, night after night? I was feeling claustrophobic, deflated and exhausted after just one day. Tomorrow’s itinerary looked worse and I had blisters already (partly due to the purchase of light trail shoes which had gotten soaked through in minutes, and moved around my feet so much more than well-fitting boots). It was only mid-March, the weather could be wet for weeks yet, and cold nights were guaranteed. Why wasn’t I at home with my family, reading my youngest daughter a bedtime story? Hot cocoa waiting. Suddenly the humdrum routine of everyday life seemed ever so enticing. For Pete’s sake, I was past 40. Give me my pipe and slippers!

Even in the shelter of the woods it was a rough night, with the whistling wind, heavy rain and disturbing dreams. The weather was still grim in the morning so I packed up on an empty stomach and moved on. No point in searching for the cave now: that ship had sailed. Local legend has it that Bruce left the fragments of his broken sword at the cave. While resting there, it seems the King had better dreams than me, he had a vision of an ‘old man with grey locks who foretold his future destiny’.5

My aim was to reach Inversnaid, where there was the appeal of locating yet another cave in which the King of Scots took shelter. There was also a ferry (weather dependent – it had been cancelled in the days prior to my departure, due to high water levels) that would take me across Loch Lomond towards the Clyde Estuary, my destination.

Retracing my steps of the previous evening, I headed west, back along the lochside road. Soon I was passing the Monachyle Mhor Hotel and in a moment of weakness I decided to check it out. This luxury establishment was washed in pink – at one time this bright finish would have signalled that the owner was a Jacobite. Encouraged somewhat by this signal, Meg and I skulked up the gravel drive in full view of the residents breakfasting in the glass conservatory. As we approached, the entrance doors were thrown open and a confident individual came striding out and warmly welcomed us in. Walking with a huge rucksack and a wet dog, I am never sure of the reception that I’ll receive at fancy establishments, so it was nice to be made to feel wanted from the outset. Inside the hotel, I retreated to a cosy bar and after shedding some wet layers I plonked myself down and relaxed. The tension in mind and body lifted almost immediately in the comforting surroundings and I splashed out and ordered a full Scottish breakfast. It was 9Am and reasonably busy; the comings and goings of the guests and staff were a welcome distraction from thoughts of my walk. While I was waiting to be fed, the waiter rushed into the bar and removed a smoke detector. I assumed my breakfast had been delayed, or worse, cremated. As the burning smell started to travel, the guy who had welcomed me stormed into the kitchen, and screamed, ‘What have you done?’ I listened intently for the next sound, surely frying pan onto bone. However, there was only a meek squeak from the kitchen and I knew there was humour, not fury, in the boss’s rant; I smiled from ear to ear.

Loath as I was to leave this establishment, at least I was cheered up, filled up and dried up by the time I dragged myself away. Back on the road I met Peter, a retired Dutch Marine, out walking his dog; he worked on the estate, so I speired him for a bit of local knowledge about the going up ahead.

At the end of the public road, I walked past Inverlochlarig farm and onto a track before crossing a bridge over the River Larig. Blocking access to the hillside was a fence built in a strong defensive position; almost, but not quite invulnerable to attack by a man encumbered by a heavy rucksack. Only by using superior and previously unknown gymnastic skills did I manage to progress (a lift and drop technique was practised on the dog). Now in open country, negotiating a river of streams cascading off the hillside, I made my way round a shoulder of Stob a’Choin, my clothes and footwear as sodden as the ground. The rain continued as I slogged uphill on the west side of the mountain. Breathless, I reached a long, level, mushy pass encapsulating a little lochan which fed the Allt a Choin. I followed this deeply cutting river as it worked its way southwards and as I descended towards Loch Katrine it became an ever more mesmerising and raging torrent. Thankfully, as it approached feeding time again, the rain relented and the clouds parted a little. Under an upliftingly bright sky, I seized my opportunity and tied my sodden tent and waterproofs to a fence, then cooked up some egg noodles whilst my washing billowed in the wind.

Beautiful Loch Katrine, at the heart of the Trossachs, has been a destination for sightseers ever since Queen Victoria sailed up the loch in 1866. The steamship SS Sir Walter Scotthas been working the waters for over a century. Don’t bring your speedboat, though; oil-fired engines are banned – you wouldn’t want to come between Glaswegians and their water supply. I reached the private road that borders the loch and in front of me was a man-made peninsula extending into the water, at the end of which was an 18Th-century Clan MacGregor burial ground – a stunning location to spend eternity.

The cave reputedly used by both Robert the Bruce and Rob Roy.