Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

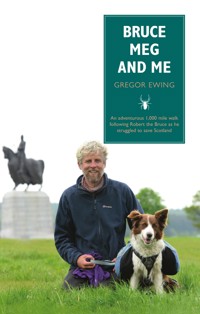

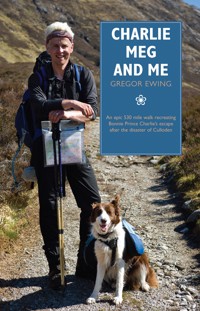

For the first time, Bonnie Prince Charlie's arduous escape of 1746 has been recreated in a single journey. The author, along with his faithful border collie Meg, retraces the Prince's epic 530 mile walk through remote wilderness, hidden glens, modern day roads and uninhabited islands. Gregor Ewing tells the Prince's story alongside the trials of his own present day journey, whilst reflecting on the plight of the highlanders who, despite everything, loyally protected their rightful prince. The author's love of history and the landscape in which he travels shines through in this modern day adventure. BACK COVER: Charlie: Prince Charles Edward Stuart, second Jacobite pretender to the thrones of England, Scotland and Ireland, instigator of the Jacobite uprising of 1945, fugitive with a price of ?30,000 on his head following the disaster of Culloden, romantic figure of heroic failure. Meg: My faithful, four-legged companion, carrier of supplies, listener of my woes, possessor of my only towel. Me: An ordinary guy from Falkirk only just on the right side of 40, the only man in a houseful of women, with a thirst for a big adventure, craving an escape from everyday life. For the first time, Bonnie Prince Charlie's arduous escape of 1746 has been recreated in a single journey. The author, along with his faithful border collie Meg, retraces Charlie's epic 530 mile walk through remote wilderness, hidden glens, modern day roads and uninhabited Ewing tells the Prince's story alongside the trials of his own present day journey, whilst reflecting on the plight of the highlanders who, despite everything, loyally protected their rightful prince. The author's love of history and the landscape in which he travels shines through in this modern day adventure. One of the strengths of this man and dog travelogue is the neat way it stitches together history with the writer's personal journey. The balance is perfect. TONY POLLARD

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 358

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

GREGOR EWING has combined his passion for the outdoors with his love of Scottish history in undertaking the six-week journey that led toCharlie, Meg and Me. Always looking to widen his knowledge of Scotland’s past, he is as happy trawling through a tome by a warm fire as he is exploring ruins and battlefields. His outdoor exploits were initially a means of gaining fitness, but after completing the Duke of Edinburgh Award and steadily ticking off Munros, he has come to appreciate the beauty and freedom of Scotland’s remote landscapes more than ever. Gregor is based in Falkirk, where he works in property management and lives with his wife, Nicola, their three daughters, Sophie, Kara and Abbie, and their dogs, Meg and Ailsa.

Charlie, Meg and Me

An epic 530 mile walk recreating Bonnie Prince Charlie’s escape after the disaster of Culloden

GREGOR EWING

LuathPress Limited

EDINBURGH

www.luath.co.uk

First Published 2013

eBook 2013

ISBN (print): 978-1-908373-61-8

ISBN (eBook): 978-1-909912-07-6

Maps © Gregor Ewing. Base map information supplied by Open Street & Cycle Map (and) contributors (www.openstreetmap.org), and reproduced under the Creative Commons Licence.

Images on page 14 and 231, and on page 1 of colour section are reproduced under the Creative Commons Licence.

© Gregor Ewing 2013

Contents

List of Maps

Acknowledgements

Foreword by Dr Tony Pollard

Notes on the text

Prologue

CHAPTER 1 Introduction

CHAPTER 2 From Culloden to Arisaig

CHAPTER 3 The Western Isles

CHAPTER 4 The Isles of Skye and Raasay

CHAPTER 5 Mallaig to Glen Shiel

CHAPTER 6 Glen Cannich then Lochiel country

CHAPTER 7 To Badenoch

CHAPTER 8 Loch nan Uamh

Image Section

Epilogue

Timeline

Bibliography

List of Maps

The Complete Journey

From Drummossie Moor to Loch Lochy

Towards Arisaig

Lewis and Harris

Benbecula and South Uist

Northern Skye and Raasay

Sligachan to Elgol

Knoydart to MacEachen’s Refuge

Crossing the Rough Bounds

To Glen Cannich then southwards

Loch Garry to Achnacarry

Towards Fort Augustus

To Badenoch

From the Cage to Glen Roy

Towards the West Coast

To Loch nan Uamh

Following the Prince’s flight

Acknowledgements

MY JOURNEY WOULD not have happened without the support and encouragement of Nicola, my wife. This book is dedicated to her and also to my children Sophie, Kara and Abbie who mean the world to me.

I owe a big debt of gratitude to the support team who helped keep the home fires burning whilst I was away: Diane, Janet, Susan, Carol, Gordon, Emma-Louise, Mum and Dad.

Thanks to Gavin MacDougall for his encouragement. The knowledge that Luath Press were behind me helped from day one of the trip.

I really appreciated all the friendship, support and help that I was given on my journey. Not least from my old friend George, my new friend Alistair MacEachen and from Deirdre MacEachen, Bob Forgie, Sarah at Arisaig House and Lyn at Raasay House Outdoor Centre,

Finally a special thanks to Kate Fawcett, Ian Scott and Kirsten Graham who proof read the manuscript, sorted out my grammar, spelling, inaccuracies and provided helpful suggestions.

Foreword

THERE IS NO better way to appreciate history than to visit the places touched by it. I constantly impress this point on my students, most particularly when studying battlefields – if you are to have any chance of understanding what happened at Flodden, Culloden or Waterloo you really need to visit the ground, walk it and appreciate the terrain – only then will you understand the decisions that commanders made and why events unfolded as they did. The same is true of any journey made by people in the past. While we cannot walk in someone else’s shoes nor perhaps not even in their footsteps, we can get an idea of the challenges any arduous route throws up and the emotions which the landscape might elicit. Anyone who doesn’t believe that only needs to read this book to be convinced otherwise.

Gregor is by no means the first person to be attracted to the epic journey taken by Charles Edward Stuart, better known as Bonnie Prince Charlie, during his time as a fugitive following defeat at the Battle of Culloden on 16 April 1746. I recall many years ago watching the TV series ‘In the Footsteps of Bonnie Prince Charlie’ with Jimmie MacGregor, and then there is the book ‘Walking with Charlie’ by Steve Lord, to name but two examples. Of course, Jimmie MacGregor didn’t walk the whole route and although Steve Lord walked more of it, he negotiated it in sections, returning to the comfort of his home for long stretches before taking up the trail again. Gregor’s journey was different – he did the whole thing in a single stint over a period of six weeks, and it’s the first time that anyone has done that, apart from Charlie of course.

One of the strengths of this man and dog travelogue, which as such takes its place alongside John Steinbeck’s aptly titled but totally unrelated ‘Travels with Charley’, is the neat way it stitches together history with the writer’s personal journey. The balance is perfect and even a supposed expert like me comes away feeling I’ve learned something thanks to Gregor taking me back to 1746 when he reaches the relevant points on his walk.

The real star of the show however isn’t Gregor, and not even his trusty sidekick, Meg the dog, it’s the landscape of northwest Scotland and the isles. I spent the later part of my childhood in that part of the world and return to it whenever possible. I would challenge anyone to read this book and not by the end of it want to strap on their walking boots and get onto the hills and into the glens. But beauty comes with a price and the unforgiving nature of the place looms large here. It is in sharing Gregor’s difficulties in coping with what, despite the roads and ferries, still comes across pretty much as a wilderness that we get a vivid idea of the straits in which the Prince found himself. It was a long walk from Culloden to the shores of Loch nan Uamh, from where the Prince was finally picked up by a French ship, and there were a lot of detours and encounters with people on the way, and the following pages do much to bring that journey without maps to life.

As an archaeologist I am perhaps most familiar with the starting point for that journey, having carried out various surveys and excavations of the battlefield at Culloden, and it was there, several years ago now, that I ended a journey into the past of my own. A friend and I had the bright idea of recreating another walk made by Bonnie Prince Charlie, the night march which the Jacobite army made in attempt to surprise the Duke of Cumberland in camp at Nairn on the night of 15–16 Arpil 1746. We decided to do it in period kit, carrying the weapons of the day and accompanied by a platoon of eager re-enactors. We set out from Culloden House, where Charles had set up his HQ, at around seven o’clock in the evening with a spring in our step and the press in tow. However, as the night drew on the fatigue set in. Swords and muskets, which at first seemed to weigh nothing, began to show their true colours. By the time we got within a couple of miles or so of Nairn, at around two in the morning, by which time I had already abandoned my sword and musket, we were all shattered and decided to a man to turn back, at a spot which can’t have been that far away from where the Jacobite army decided to call it a night. So, we turned and headed back, this time for Culloden battlefield.

I arrived there at around five thirty in the morning to find just a couple of the others hanging around. Plans to have some sort of assembly at the clan monument were forgotten as weary men melted away back to their homes. It was at that point I realised I could barely move – my thighs and nether regions were in agony after wearing a kilt (full plaid) for over 20 miles. When I got back to my hotel – which shamed me as those who made the journey in 1746 then had to fight a battle – I could barely make it into the bath. Later that day I learned that less than half the party had made it back to Culloden without the aid of a support vehicle and one among us was in hospital after going over on his ankle in the dark.

There had been some talk of retracing the Jacobite march to Derby, a much more ambitious undertaking, but after that night it was never a conversation injected with much enthusiasm. The Nairn walk had however been a success, in that it had shown just how big a mistake that march in 1746 had been. The Jacobites would have been far better off getting what rest they could before the battle rather than wasting all that energy on what turned out to be wild goose chase. That experience also helped me appreciate just how big an accomplishment Gregor’s epic 500 mile journey had been, and for that I take my blue bonnet off to him. There is a rumour that his next expedition will follow the advances made by the Marquis of Montrose in the mid 1600s. If it is then I hope the road rises up to meet him, and Meg of course.

Tony Pollard

Loch Fyne

February 2013

Notes on the text

Although I believe imperial measures give most people a better sense of perspective (thus my subtitle!) I had no option but to think metric during my journey because that’s the way maps are made. I apologise to any imperial thinkers, but as a reminder:

Everyone has their own method of working this out, but to get miles I half the kilometre distance and add 20 per cent.

Where Gaelic words are included in the text, landscape features are named as they appear on Ordnance Survey maps. A few of the more commonly repeated words are:

‘Bealach’ Pass or a low point between two hills

‘Allt’ Burn or stream.

‘Coire’ Corrie, a hollow in the side of or between two hills.

‘Sgurr’ Rocky or steep peak

‘Beinn’ Mountain or peak

‘Meall’ Rounded hill

‘Sron’ Nose, point

Prologue

ON 23 JULY 1745, Charles Edward Stuart landed on the Isle of Eriskay in the Western Isles. With no money, arms or troops and only seven attendants he aimed to restore his father, James, to the unified throne of England, Scotland and Ireland. The Prince had not set out from France entirely empty handed, but a second accompanying ship carrying 700 troops, money and armaments was badly damaged in a skirmish with a British man-of-war en-route, and was forced to return to France.

Without French assistance, Highland chiefs who had previously pledged their support, now refused to rise, but, by the sheer force of his personality, Charles managed to convince them, one by one, to rally to his cause. In a key moment at Arisaig, Charles convinced Donald Cameron of Lochiel to raise his clan, support which was instrumental in helping the rising to gather momentum.

The standard was famously raised at Glenfinnan on 19 August 1745. Significant numbers of men were rallied; Lochiel provided 700 Camerons and MacDonald of Keppoch brought 300 of his clansmen. The government’s response was to offer a £30,000 (approximately £1,000,000 in today’s terms) reward for the capture of Charles.

The Jacobites travelled light and fast, moving south over the Corrieyairack Pass where a government army commanded by General Cope refused battle and retreated back to Inverness. The Highlanders formed an immediate bond with their Prince, who led from the front and marched with the men.

Thus, by early September with hardly a blow struck, the town of Perth was captured and occupied in the name of James VIII. Charles appointed Lord George Murray as Lieutenant General. Murray was a capable soldier, but the subsequent breakdown in the relationship between these two men was a key factor in how the campaign eventually played out.

Edinburgh was captured without bloodshed on 17 September. The Highlanders streamed into a gate left open by the deputation who had been parleying with Charles outside the city. The Prince was declared regent and housed himself in Holyrood Palace.

Bonnie Prince Charlie (1892) by John Pettie.

At Holyrood with young MacDonald of Clanranald on the left and Cameron of Lochiel on the right.

On 21 September, the Jacobites won the Battle of Prestonpans, defeating General Cope’s government troops in less than ten minutes. The only army in Scotland opposing the Jacobites was removed.

Charles established his reputation as the young chevalier: magnanimous, handsome, popular. On 10 October, he issued a declaration to revise the Act of Union between Scotland and England. (McLynn, F;Bonnie Prince Charlie; Pimlico, London; 2003)

A council of war was held to consider an invasion of England. A vote was taken and the decision to invade was made with a majority of only one vote. Charles wished to attack General Wade’s army at Newcastle, but he eventually acceded to Lord George Murray’s invasion plan, avoiding the confrontation with Wade’s forces.

In November the Prince crossed into England at the head of 4,500 troops, and after a brief siege Carlisle was captured. The march south continued without any interference but, other than a regiment of 400 formed at Manchester, few rallied to the Prince’s cause.

On 5 December, the army reached Derby having avoided any set battles and outmanoeuvring the opposition at every turn. The downside of this strategy was that there were now government forces to their flank as well as behind them. Furthermore, a Hanoverian spy informed the Jacobite council of war that a third government army was waiting at Northampton, ready to protect London.

The Jacobites were hindered by the lack of credible intelligence available to them. They were unaware that this third army was a fabrication. Neither did they realise that General Wade’s army was still many miles behind them, nor that the Duke of Cumberland’s army may not have been able to intercept the Jacobite army had it made a dash for London (Duffy, C;The ’45; Cassell, London; 2003).

With no additional military aid arising, Charles’ promises of a French invasion and, significant support from English or Welsh Jacobites had been laid bare. A council of war voted unanimously to retreat, much to the Prince’s contempt.

The retreat began on 6 December, with Charles in a sour mood. English towns were much more hostile on the way north. A skirmish took place at Clifton, 12 days later, where Cumberland’s Cavalry and Dragoon infantry were rebuffed. The Prince refused to release more troops preventing a possible full-scale victory.

On 26 December, the Jacobites entered Glasgow and Charles reviewed his army on Glasgow Green. The Prince found few active supporters in this town, which had gained prosperity since the Act of Union.

On 17 January, the Battle of Falkirk took place on the moors above the town. General Henry Hawley’s forces were sent packing back towards Edinburgh. Charles wanted to follow up the victory by marching on the capital right away but Lord George Murray opposed this. With the support of the Clan Chiefs, Lord George wanted to retreat to the Highlands to re-launch the campaign in the spring, which Charles reluctantly accepted.

With Charles ill, leaving the command of his forces to Lord George Murray and others, the Jacobites achieved various small victories against the remaining government troops in Scotland. However, as Cumberland’s army approached, the Jacobites failed to defend the River Spey, a key geographical barrier.

An audacious night attack on Cumberland’s army was abandoned on 15 April. At 2am, Lord George calculated that the Jacobites would fail to reach the government encampment before first light and called off the attack. (Duffy, C;The ’45; Cassell, London; 2003)

Etchings of Charles Edward Stuart and William The Duke of Cumberland.

Courtesy of Inverness Museum and Art Gallery

Despite the protests of Lord George Murray and others, Charles was determined to do battle at Culloden on 16 April. The tired, out-numbered Jacobites were drawn up on Drummossie Moor to await the Duke of Cumberland’s army.

(Except where otherwise noted, based on dates and events contained inItinerary of Prince Charles Edward Stuartby WB Blaikie and published by the Scottish History Society in 1897.)

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

I HAVE HAD A long felt desire to escape to Scotland’s hills. To spend weeks amongst stunning scenery that stirs the blood, high mountains, wide valleys and hidden glens. Enjoying unbounded freedom and tranquillity in an unspoiled landscape. Being in tune with oneself, melding with the natural environment; reaching a mountaintop with stunning views in all directions; wild camping beside an overshadowed lochan or on a small plateau beside a mountain stream; enjoying the primitive calmness of sitting, well fed, around a campfire; the fulfilment of resting with a light-headed tiredness that comes after a day’s exertion; being totally responsible for oneself and buzzing from the increased confidence that self-sufficiency brings. All this may sound a little naïve: you can be soaked through to the skin in no time and walking in mist all day. The novelty of camping can soon wear off. Injuries can happen. Crucial equipment can be forgotten, broken or left out in the rain. Midges can drive you to murder/suicide/another continent. Countless things can go wrong. But even after years of experiencing what Scotland’s outdoors can throw at you, the desire still burned bright.

For a long time, such a journey was simply a pipe dream. I had a busy job, and a young family. Could the desire be simply a reaction to an increasingly difficult career and the responsibility of family life? Where was that free time I enjoyed when young and single? And what had I donewiththat free time? Sadly, precious little. Now when I wasn’t helping around the house, entertaining the kids or working extra hours, I really appreciated time alone. The occasional weekend was the best I could muster. Climb a few hills, stay out overnight, climb a few more hills and home. Great fun? Yes! But it still didn’t placate my desire, I needed something more. I wanted my escape to be a sufficient length of time to shake off the modern world. A chance to draw breath and take stock, allowing reflection to happen at a natural pace. Tuning in to my surroundings and allowing the mind to relax, whilst pushing myself physically to see if I could survive for a sustained period of time.

As the years passed, the desire lingered just below the surface, popping up on holidays in the West Highlands or occasional camping weekends. Then in 2010, ironically thanks to the economic recession, came the opportunity to fulfil the dream. I had been running a family owned retail business operating in Falkirk. But from 2007 trading became increasingly difficult. The credit crunch saw people spending less on big household items such as carpets and furniture, the very goods on which the family business had been founded. Three years later I made the difficult decision to stop trading. Keeping this a secret while I took time to make doubly sure it was the right decision was terrible and the pressure weighed heavily on me. A summer holiday in Dumfries nearly ended in divorce. However once I had told my family, staff, customers and suppliers a great weight was lifted from my shoulders and following a final sale the business stopped trading.

Whilst searching for a new career, I realised I had an opportunity to make my escape. At the same time my kids were all now at school and that little less dependent on my wife, Nicola and I. True, I seemed to spend an increasing amount of time as a taxi driver but we had now shifted to the stage where my daughters wanted pals not parents. The guilt at the thought of leaving them all for a few weeks began to dissipate and with the big 40 just around the corner and the realisation that I wasn’t getting any younger, the thirst for the big adventure loomed larger than ever.

I needed a plan. Disappearing into Glen Affric for a few weeks didn’t appeal for an extended journey. Despite the beauty of the surroundings, how would I fill my time once I was there? I could climb all the hills in the locale, swim in the loch and hang out at my campsite but this lacked purpose. I wanted to undertake some form of meaningful journey in the hills. Being keen on history, I have always been fascinated with the old tracks, pathways and coffin or drove roads that criss-cross the landscape. The lesser known the path, the better as the feeling of discovery always added to the fun. To walk on an ancient pathway thinking of ancestors who traipsed the same roads for a particular purpose added another dimension to any journey. I decided then that I wanted my escape to combine history and remote terrain. I needed a substantial journey with some form of historical significance. That is where I turned to the story of Bonnie Prince Charlie and his wanderings.

Having spent a good deal of time in the north-west of Scotland, the Jacobite Rising of 1745–46 fascinated me greatly. In this area, the Prince landed and raised the Highland Clans before marching south at their head. From here, he left in 1746 having survived for five months as a fugitive after his army was defeated at the battle of Culloden. The associated monuments, cairns and caves dotted all over the Highlands made me realise the importance of the Prince to the history of the area, and it was his escape in the Highlands and Islands after the Rising failed that interested me most. Charles fought a physical and mental battle to outwit the forces seeking to apprehend him. This journey is recorded as his finest hour and consisted of exactly the type of terrain that I wanted to escape to.

With the Jacobite army soundly defeated at the Battle of Culloden, the young Prince had to move swiftly to avoid capture by the victorious troops. Riding away from the battlefield after a failed attempt to rally the troops, he headed for the west coast to try to find a ship from which to return to France. Within a couple of days of his defeat, Charles was on foot, deep in the highlands, moving from glen to glen, travelling light and living rough with just a few followers. For the next five months he remained a hunted fugitive with a £30,000 (a six figure sum in today’s money) price tag on his head. Pursued by the Duke of Cumberland, the British Army and Highland Militia as well as by ships from the British Navy, Charles undertook an arduous flight across land and sea. An incredible journey stretching across the Highlands and Islands and back again as he sought to avoid capture and escape to France. Finally, after one of the most gruelling experiences anyone, never mind a royal prince, has ever had to endure, he escaped Scotland aboard a French ship from Loch nan Uamh in September 1746, intent on coming back to relieve the Highlanders of the plight in which he had left them.

This journey seemed to me to have everything I was looking for. A well-documented historical trail to follow through often remote and mountainous terrain. Lots of opportunity for wild camping in beautiful locations. A physically demanding challenge, requiring a high degree of self-sufficiency. Following in the footsteps of one of Scotland’s most renowned characters there would be an opportunity to get to know the man as well as the myth. There was plenty of reading material to be getting on with, so I did my research and made a plan. There are good books detailing the Prince’s escape and some authors have travelled sections of the route. But no one had attempted to recreate the journey in a single outing. I decided to make this my goal, recreating as accurately as possible his movements during the period of flight. Travelling with me would be Meg, my five-year-old border collie. In the course of the journey I would visit all the sites that Bonnie Prince Charlie frequented, including houses, castles and caves.

I dug out 1:50,000 Ordnance Survey Landranger Maps and started plotting. Having planned many hill-walking trips, the same principles still applied, although this was many times bigger than any journey I had undertaken previously. From the descriptions I had of the Prince’s escape, I started to transfer his route to the map. Sometimes the planning was easy, as a more modern path or road has simply replaced the old path that the Prince followed. In fact, some sections of General Wade’s roads built after the Jacobite rising of 1715 and which Charles occasionally used remain today. On other occasions following the route accurately meant foregoing paths and looking to find a realistic way through glens and across hills.

I love maps, your index finger following a route, spotting points of interest whether it is a cave, a cairn or a section of General Wade’s military road. With unbounded enthusiasm I poured over maps tracing out the Prince’s route. On a few occasions how he got from one location to another is unknown, but in the main I followed W.B. Blaikie’sItinerary of Prince Charles Edward Stuart; from his landing in Scotland, 1745 to his departure in 1746(Scottish History Society, 1897). This was constructed from first hand journals and accounts in theLyon in Mourningby Bishop Forbes, published by the Scottish History Society in 1895.

Sometimes I would have to walk the modern, traffic-bearing road rather than a nearby path because that was the route the Prince took. My decision to be accurate wasn’t always going to produce the best excursion! Based on previous experience and taking my backpack into consideration, I estimated that I could travel 26km (approx. 16 miles) per day. Overall, the approximate pace would be four kilometres (2.5 miles) per hour, not including rests, and on climbing days the distance would be reduced according to the total amount of height to be gained.

One day a week I would rest my legs. This was intended to be a tough physical challenge but one I was determined to enjoy. It was not a punitive speed march. During walking days I also had to retain enough energy to make camp, record my thoughts and cook a decent meal. I had been in situations before where I had arrived back at a campsite so exhausted that I had unzipped the tent, crawled in and crashed out without food or drink. Being on my own, I couldn’t afford to be blasé with my well-being or timetable.

Quite soon I had a rough plan. Travelling through the Northwest Highlands, the Outer Hebrides, Skye and Raasay, I would be walking just over 800km (500 miles). Taking in a combination of modern roads, paths and trackless mountainside wherever the Prince’s party had walked. There would also be 500km (300 miles) of ferry and bus journeys. Amongst the sailings made by the Prince were journeys from Arisaig to Benbecula and Elgol to Mallaig. No modern day ferries run these exact routes so I would walk to the water’s edge where the Prince embarked and then take public transport to the relevant ferry port. After the ferry crossing, I would make my way to the point where the Prince landed. Reconstructing the journey in this way, I would still be walking almost exactly where the Prince walked in 1746.

In the main, I would rough camp and sleep in my tent, trying to make sure that my campsites were located in as interesting but sheltered places as possible. I would also make use of a few bothies, the odd hotel and one hostel. There are also a number of caves associated with the Prince, ranging from a tiny one near Loch Arkaig, to a more commodious affair at Glen Moriston with its own running water. I tried to organise my days so that I would end up at a cave as often as possible. Whether I would sleep in them would depend on their (and my) condition. Not only would I follow Charlie, I also hoped I would get to understand him a little better by putting myself through a very similar set of circumstances to that which he experienced. Sure, government forces weren’t chasing me, and robbing a bank without a mask just to get hunted wasn’t a realistic option. However, many things would be the same including the distance travelled, the terrain, the weather, the scenery, the fatigue, the midges, and the insecurity of completing the journey. As I would be alone during the journey I would also have to deal with loneliness and be almost completely self-reliant.

Courtesy of Jim Barker

The overall terrain has changed very little in the intervening 266 so my experience of the route would be very similar to that of the Prince. The main exception was the time of travel. Quite often, the Prince journeyed at night and rested during the day to avoid observation. I would stick with daytime travel. Enjoying my surroundings was essential to me. Survival instinct also kicked in. Crossing unknown and rough territory at night could too easily result in a sprained ankle. Even walking on modern roads at night could be a recipe for disaster! I hoped, by following his epic route, having already done the background reading that I could get inside his head. I wanted to explore his motivation and to see if anything about this final farewell to the Highlands affected his future thinking. The rights and wrongs of the Rising of 1745–46 still spark heated debate.

Supporters would argue that he was justifiably trying to restore his family, the Stuarts, back to their rightful position as monarchs of England, Scotland and Ireland. Initially stoked with great drive and determination, he very nearly succeeded. Arriving with only a few advisors, no weapon supplies, monies or soldiers he convinced the Highland chiefs to support him, and the Rising snowballed until within five months he was at Derby and within striking distance of London. Only the absence of promised support from France, and the failure of English Jacobites to rise to the cause prevented him from claiming the throne for his father. We will never know whether this support was necessary for success, but it was certainly necessary to convince Charles’ Council of War to march on to London.

Others see the Prince as a reckless youth who was wrong to start a rising with only promises of support from France and the English Jacobites. He also lacked due regard for the consequences for the people who supported him. When things went badly, as they ultimately did, then the Highland Clans would pay a high price for supporting him. Having spoken to a quite a few people from the Highlands during research for my trip I was surprised, perhaps naively, by the strength of feeling that the Jacobite Rising of 1745 still generates. I determined to find out during my journey how Charles was viewed amongst the descendants of those who rose for the Prince and who suffered in the aftermath of Culloden as the Government dispensed fire and sword amongst the clans.

With my trip still some way off, I started to work on my fitness regime and took up running again. Using canal towpaths, old drove roads or forest tracks, I always tried to head off-road for clear air, better scenery and so that my dogs could run freely. The next step in my plan of action was to get out on the hills again. Having notched up about 150 Munros over the years, I had lost interest in doing many more as I was spending more time in the car to reach them than I was on the hill enjoying them. However, this time round I headed for the Ochil Hills, just a short drive away, refreshing map reading skills, getting used to carrying a pack again, and reminding my legs of the joys of going uphill.

With my wife, Nicola, and three young daughters to consider, disappearing for six weeks on a self-fulfilling journey seemed slightly selfish to begin with, particularly as Nicola also worked full time. Perhaps if I explained my reasoning I could just about make it fly. So one Friday night, whilst watching TV with Nicola, I gathered enough Dutch courage to blurt out my plan as fast as I possibility could.

‘I am going away for a six week walk.’

‘What!’

Slower this time, ‘I am going away for a six week walk.’

‘When?’

‘Next year.’

‘Who with?’

‘Meg.’

‘Where?’

‘The Highlands.’

‘Why?’

‘Because I want to do something different.’

‘What?’

‘Follow Bonnie Prince Charlie.’

‘He’s deid! What about me? What about the kids? Who’ll look after Ailsa? [The other dog] Who’ll take the kids to school? And my fitness classes? Who’ll babysit? When exactly are you going? Who’s going to help me? My mother can’t do any more. What about your job? HAVE YOU THOUGHT THIS THROUGH?’

All perfectly plausible questions, I just wasn’t expecting them all at once.

A few weeks later I slipped into a conversation ‘I need to do a practice…’

So a few months later my eldest daughter, Sophie and I completed the 98-mile West Highland Way. We carried our own gear, well not quite true, I carried my gear and I carried her gear. She was aged only 11 after all. We took seven days to complete the journey, camping out at night. The scenery was stunning, my daughter and I got on well together, I learned a few lessons for my next adventure and we raised some money for charity.

I ended up setting a target weight for my rucksack of 20kg for the main mission. I had carried 28kg on my practice expedition and it was too much. To start with, I wouldn’t be carrying my daughter’s gear as I had previously. Then I changed some of my older camping gear for newer lightweight versions: sleeping bag, tent, and stove. I added some extras like an inflatable mattress and a lightweight chair frame. Not necessary for a shorter trip, but essential to have some comfort for this length of journey. My sustenance would in the main be dried food and I would carry seven days’ worth at a time, re-stocking either at shops or with some carefully hidden supply bags, which I would place in remote locations before I left. There would be no Highlanders out foraging for me. Keeping spare clothes down to a minimum, I cut other items from my inventory mercilessly. Happily passing some of my equipment on for Meg to carry, I brought the rucksack weight down to just less than 20kg.

Meg, my five-year-old collie, was the unfortunate victim of my campaign to cut down my backpack weight. Six weeks before, I bought a doggy rucksack and started making her go out in public with it. Dogs that we had met countless times on previous walks now started coming up to her and barking their heads off as if to say ‘What the hell are you wearing that for? If Bob and Betty see you with that, they’ll be buying one for me next week and then my street cred will be zip, just like yours!’

With my route planned out, feeling fit, rucksack packed and family appeased, I was ready to go.

From Drumossie Moor to Loch Lochy

CHAPTER 2

From Culloden to Arisaig

THIRTY MINUTES AND it was all over. Bonnie Prince Charlie was led from Culloden field in tears, his previously unbeaten army routed. Unable to accept responsibility for defeat, he claimed he had been betrayed. In truth however, he had been determined to make a stand on this hugely unsuitable battlefield despite the pleadings of his senior military advisers. Insurmountable odds were stacked against the Jacobites and the Duke of Cumberland’s government army exerted a killing blow on the rising.

The Highlanders who lined up on Drummossie Moor on 16 April 1746 were tired and hungry after an abortive attempt at ambushing Cumberland’s forces the previous night. Five thousand weary men lined up on a battlefield poorly suited to them, facing 9,000 well-drilled government troops. Virtually without reply the government artillery decimated the Jacobite ranks as the men awaited the order to attack. When they eventually did charge, their lack of numbers and the poor ground prevented them from breaking the enemy’s line. The Jacobites were soon swept aside by an army that outgunned them in all departments: number of troops, morale, discipline, weapons, artillery and leadership.

Now began the final act of the Jacobite Rising of 1745–46. Redcoats and Highlanders loyal to the government pursued Charles through the heather, across the hills and over the seas, determined to destroy the man who had come close to unseating the Hanoverian monarchy. Those that had supported Charles would pay a high price over the coming hours, days, weeks and months.

Today the National Trust for Scotland cares for Culloden Battlefield. It features a dominating memorial to the clans and a state of the art visitor centre; the battlefield has been restored to resemble its appearance in 1746. As I arrived, 266 years later, on a dark April morning, with a blanket of snow on the ground and an icy wind blowing across the exposed moor; it was an eerie and intimidating place to be. I marched onto the field of battle, in the company of a small group of volunteers from the Culloden Battlefield Experience, whose attire added colour to the bleak landscape and whose cold steel helped set the scene. After just a few moments visualising the death and destruction that had stained this ground, I was ready to take my leave.

A Highland Charge

Courtesy of National Trust for Scotland

Charles’ flight from the carnage took him to the houses of various allies and friends as he crossed the country, initially on horseback, seeking escape from the chasing government forces. Ending up at Arisaig on the rugged west coast he sailed for the Western Isles, hoping to charter a ship for France.

Following the Prince to the coast, I would cover a distance of 140 kilometres. Taking five days in total, the first three would be on roads and good paths giving me a chance to acclimatise to the rigours of the walk. The next two days would be through rougher territory. As O’Sullivan, one of the Prince’s companions, put it, ‘the cruellest road.’

With people milling around, my departure from my wife and children was a little restrained. With freezing temperatures it was also quite hasty. I exited the battlefield with a tear in my eye, a trusty Richard Cadey from Radio Scotland as myaide-de-campe