9,90 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: BABARYBA

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

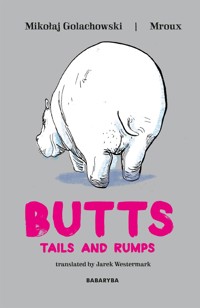

Mikolaj Golachowski

BUTTS TAILS AND RUMPS

translated by Jarek Westermark

narrated by Sean Palmer

illustrations by Maria Mroux Bulikowska

Discover the fascinated mysteries of animals’ butts! Is a hippopotamus hiding a helicopter on its rear side? Or a penguin – a cannon? Why is baboon’s ass red, and why does a tapeworm have no ass at all? Why do dogs keep sniffing one another, and why wouldn’t cats ever stop licking their fur? And why does the roe flash its white rump? This book contains thirty exciting and funny stories of butts, tails and rumps narrated by a science promoter and a biologist in one.

Mikołaj Golachowski – PhD in Animal Ecology and Zoology, traveller, translator and polar explorer. When he’s not busy in the midst of Antarctic snow and ice, he lives in Warsaw and writes about animals and protecting the environment. Author of educational and popular science books.

Maria Mroux Bulikowska – illustrator working with children’s and adult books and magazines. Author of two books on Warsaw dialect.

Table of contents:

01 INTRODUCTION

02 THE BOMBARDIER BEETLE

03 THE HIPPO

04 THE HERRING

05 THE POLAR BEAR

06 THE PENGUIN

07 THE WOMBAT

08 THE DOG

09 THE CAT

10 THE PARAMECIUM

11 THE WEAVER

12 THE MAYFLY

13 THE DUCK

14 THE PEACOCK

15 THE ORCA

16 THE LIZARD

17 THE KANGAROO

18 THE WASP

19 THE SPIDER

20 THE SEAHORSE

21 THE FROG

22 THE ROE

23 THE LYNX

24 THE SCORPION

25 THE EARWIG

26 THE TAPEWORM

27 THE SNAKE

28 THE SKUNK

29 THE BABOON

30 THE SPIDER MONKEY

31 THE FIREFLY

Mikołaj Golachowski - Butts, tails and rumps

translated by Jarek Westermark

narrated by Sean Palmer

illustrations by Maria Mroux Bulikowska

ISBN 978-83-67356-19-0 (audiobook)

Wydawnictwo Babaryba

www.babaryba.pl

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Table of contents

INTRO

THE BOMBARDIER BEETLE

THE HIPPO

THE HERRING

THE POLAR BEAR

THE PENGUIN

THE WOMBAT

THE DOG

THE CAT

THE PARAMECIUM

THE WEAVER

Text © Mikołaj Golachowski, 2014 Illustrations © Maria Bulikowska, 2014 This edition © Babaryba, 2023

Concept and editing: Marek Włodarski Fact checking: Jakub Urbański Book design: Maria Łepkowska Proofreading: Katarzyna Szajowska & Jamie Watts Translated by: Jarek Westermark

Wydawnictwo BABARYBA www.babaryba.pl

ISBN 978-83-67356-18-3 WARSAW 2023

The electronic version was created by Elibri

For Hania Mikołaj

INTRO

Every animal has at least two ends. Up front: a snout, beak, or chelicera. And in the rear… a butt! And it’s the butt that is often more fascinating than the critter’s snout. We all have a butt of course, but we sometimes forget to pay it the attention it deserves. Now is the time to change that!

There are more butts in heaven and earth, than are dreamt of in our philosophy. For who could dream up the armoured butt of an Australian wombat? Or the alchemical workshop that the bombardier beetle carries in its behind? And if we throw various fancy tails into the mix, we’ll see that nature chose the animal butt as a hiding place for many fascinating secrets and phenomena! So let’s get to know animals… from the bum forwards.

THE BOMBARDIER BEETLE

THE BOMBARDIER BEETLE

Explosive farts

Releasing pungent gasses from the butt is nothing special – anyone can do it! But some animals have achieved true Olympic greatness in this field. Among insects, an indisputable master is definitely the bombardier beetle. Its polish name translates to cannoneer, which is fitting, because it uses its butt as a cannon (or bombard!) to fire away at its foes.

The beetle is a real life magician and it houses a secret lab in its butt (or thorax, as an insect’s behind is called). This lab consists of a couple of chambers separated by tough walls. Each chamber is really tiny, seeing as our beetle is just a centimetre long, and one of them stores two different liquids.

When the bombardier is approached by an enemy such as a frog, spider, or swarm of ants, the two liquids stream to another chamber. There they are mixed with a third which acts as an igniter. This second chamber, protected by thick walls, ends with two tubes positioned on both sides of the insect’s bottom.

The beetle points its thorax towards the enemy and unleashes a series of salvoes aimed straight at its nose! The foe gets sprayed with a corrosive fluid that’s almost as hot as boiling water! If he survives this by some miracle, he will most certainly learn his lesson and never bother the bombardier again.

The beetle itself – also a predator, we might add – isn’t bothered at all by its own cannonade. Although its butt facilitates an actual explosion, the thick walls of the blast chamber guarantee its safety. Once the foe is dealt with, it can start looking for tiny creatures to feed on, enjoying the peace and quiet.

THE HIPPO

THE HIPPO

A butt-helicopter

Everyone has a butt, but not everyone’s butt has a small fan attached to it! The hippo – considered one of Africa’s most dangerous animals – can boast just that.

This giant denizen of the mother continent has a short, chunky tail which can be quickly thrashed around. Though it doesn’t actually spin like a propeller, but rather swings from side to side in a pendular movement, the hippo shakes it so rapidly that it looks like it’s about to achieve lift-off.

The hippo always starts waging its tail when it does its business, scattering poo and pee in all directions, making sure it lands as far as possible – up to a couple of metres away. Disgusting, right? But this is by design!

A hippopotamus will aggressively defend not only its favourite muddy riverside pond but also its many wives. If it comes face to face with a rival, a long and dangerous fight might ensue, during which both sides make use of their overgrown teeth.

That’s why hippos spread their stinky “perfume” so vigorously. When another hippo comes across the host’s smelly pee and poo, it quickly realises the territory is already claimed and that it must skedaddle to avoid getting bitten.

For the curious

The word hippopotamus means “river horse” in ancient Greek. While the hippo might not have a horse’s good looks, these giant animals do inhabit rivers and lake shores. They spend all day in shallow waters, snoozing, swimming and bouncing gracefully on the bottom. When submerged, the hippo is no longer ponderous and clumsy. Instead, it becomes a regular ballerina. And no wonder! Its closest relative in the animal kingdom is, after all, the whale! Yet hippos still go ashore to grab a bite. Every evening they wander their favourite grazing grounds to stuff themselves silly with grass.

THE HERRING

THE HERRING

Tracer farts

A herring’s butt is nothing fancy. Just a little hole at the tail-end of a fish. What comes out of it, however, is truly fascinating! Though farting is frowned upon (and sniffed at!) by humans, herrings view it very differently.

During daytime, when one herring notices that other members of its group swim left or right, speed up or slow down, it immediately does the same, and the herrings behind it follow suit. That’s why a shoal of fish moves like one giant organism. But at night they communicate differently.

A herring peeks out of the water to swallow air which fills its swim bladder and is then released through an opening next to the anus. Though the ensuing bubbles aren’t actually farts, as the gas doesn’t pass through any intestines, they show up close enough to the herring’s butt for us to call them that. When a herring releases bubbles, all of its friends pay close attention, as if they were receiving an important message. It’s a means of communication.

The release of highly pressurised air is accompanied by high-pitched sounds. Herrings and their related species (such as sardines) hear much better than most other fish. That’s why the sounds they make don’t attract the attention of predators. However, dolphins and whales, who consider herrings a delicacy, can pick up on all the farting and consequently munch on the shoal with gusto.

THE POLAR BEAR

THE POLAR BEAR

The emperor’s plump but

Animals don’t wear warm clothing, so to protect themselves from the cold they need either thick furs or a thick layer of fat. Or better yet: both. The Arctic, a huge region surrounding the North Pole, is one of the coldest places on Earth. Therefore it should come as no surprise that one of the fattest butts on the planet belongs to the king of the Arctic: the polar bear.

This biggest and most predatory of all bears can have a subcutaneous fat layer as thick as ten centimetres. It’s also clad in a fur so dense that he stays warm even in the middle of arctic winter. It will sometimes lie down on the ice just to cool himself! Although its behind is the biggest and roundest of all bear butts, the tail that adorns it is actually the shortest.

The polar bear might look like an overgrown teddy bear, but it’s a true athlete of the animal kingdom. It’s the biggest and strongest of all land predators. A full-grown male can measure even three meters in length and weigh up to 700 kilograms. Polar bears run much faster than humans and are excellent swimmers. They can swim as far as 100 kilometres in one go!

For the curious

Amid the ice and snow of the Arctic the polar bear hunts anything that moves. Seals are its pray of choice, but it can also overpower a walrus or even a small whale. The polar bears’ favourite food is the lard of their victims. It gives them loads of energy to grow ever fatter themselves.

Polar bears do not hunt penguins, although they are often depicted together. This is because penguins live on the other side of the world – way down south in the Antarctic. Never has a polar bear crossed paths with a penguin outside of a zoo.

THE PENGUIN

THE PENGUIN

Cannon in the bum

An otherwise unassuming butt can hold secrets undreamed of by philosophers. Monumental forces might lie behind a seemingly regular butthole! Case in point: the penguin.

The penguin is a curious creature. It is a flightless bird, like the ostrich or kiwi. It waddles about but wears an elegant black tailcoat while doing so. It can cover great distances and is an excellent climber. When submerged, it feels like a fish in water – or, rather, it feels better than fish do, as it easily catches and swallows them whole.

Even such a sharply dressed dandy has to poop sometimes. But how do you do it, if you can’t leave the nest for fear of your eggs or nestlings freezing to death or getting eaten? In the penguins’ home down in the Antarctic there are special ways to solve this problem. Enter the magical talents of a penguin’s rump. To avoid soiling their own nest (who’d want to live in a home filled with poo?), penguins approach its edge, raise their tails and fire away with tremendous force. Their droppings can sail through the air for half a metre before hitting the ground… making the penguin the only bird to be outflown by its own faeces

The penguin chooses a different spot at the edge of the nest each time, so after a while the traces of its flying droppings reach out in all directions like rays of sunlight. Depending on its last meal, a penguin’s poop can be either white (after it eats fish) or pink (if it munches on krill – small animals similar to shrimp). Against a backdrop of dark rocks, such a colourful poop-star looks truly striking!

THE WOMBAT

THE WOMBAT

Toughest bum in the world

Wombats are said to be cheerful, happy and pleased with life… at least until someone reminds them of how fat their butts are. And yet a wombat’s butt is something to be envied, for it is truly exceptional. In fact, it’s the toughest butt in the world! A bona fide skin-shield, a hyper resistant piece of armour able to withstand not only a predator’s teeth and claws, but even fire.

When a wombat is attacked, it quickly escapes into its burrow and plugs up the entrance with its bum. It calmly shrugs off any predator’s bites, ensuring the safety of its family.

A wombat’s bottom is also an effective weapon! The wombat can purposefully make room for the attacker and wait until it sticks its head deeper into the den. Then it quickly stretches out its strong hind legs to strangle him or even crush his skull against the burrow’s ceiling.

A wombat’s poop is the driest in the animal kingdom, as these Australian marsupials eat only plants and digest them very slowly. A plant’s remains can be excreted even up to fourteen days after its consumption! During this time the wombat’s body sucks it dry of not only nutrients but also moisture. This is crucial in the dry Australian climate.

Wombat faeces break into small boxy lumps inside its body. The result is cube-shaped poos. This can make pooping awkward and painful. The wombat’s really lucky that its butt is as tough and resilient as it is!

For the curious

Wombats are marsupials of sunny Australia. They are often called nature’s bulldozers. Their muscular thickset bodies are perfectly adapted for digging burrows. Even the wombat’s pouch – unlike in other marsupials – faces backwards, so that dirt doesn’t get inside it during tight squeezes in underground tunnels. And this is why little wombats must get past their mom’s bum to enter the pouch.

THE DOG

THE DOG

A smiling but

What does a butt do? The answer seems pretty obvious! It houses the hole, through which everything we’ve eaten – and no longer need – eventually comes out in the form of poo. But for many animals their rear end also plays an important part during everyday encounters. When two people meet, they shake hands. For dogs, an equivalent of that gesture is sniffing each other’s butts! Imagine if people tried greeting their friends that way …

The aroma of a dog’s behind is packed with information about that dog. A sensitive nose can gauge its sex, health and the last meal it had. Just the fact that a dog lets someone smell its butt denotes a positive attitude. But you don’t need to stick your nose under a dog’s tail to find out its mood. If the tail is raised high, its owner feels glad and confident. But confident doesn’t necessarily mean friendly – the dog might be excited because it’s planning to bite someone, for instance, or maybe it just wants to show everyone who’s in charge.

When a dog is afraid of something, its tail disappears between its legs, covering the butt to block out any smells so that (hopefully) no-one notices the dog at all!

Dogs also use their tails to smile. If a tail is barely twitching, that’s an uncertain little smirk. But when it’s wagging wildly from side to side… now that is a grin from ear to ear! Each wag fills the air with purest canine joy

THE CAT

THE CAT

A gleaming but

Everybody knows that the bum should be kept clean. Some take this more seriously than others however. In the field of butt-cleaning, few can rival the cats, as they’re famous for washing their behinds basically all the time.

As far as cats are concerned, the world can stick its problems where the sun don’t shine and they’re all too happy to show everyone where that is. All they care about is hygiene.

Just like dogs, cats have an excellent sense of smell. An unwashed butt allows them to glean a lot of information about its owner. Information which said owner would usually rather not share.

Cats are very discrete and usually think that the less everyone knows about them, the better. That’s why they scrub their butts even when they’re already clean as a whistle. They also do it when something unexpected happens and they’re not quite sure how to react.

People living with cats often suspect that their pets wash their butts so as to not appear silly or scared. It’s like they’re saying: “I was most certainly not afraid of that loud bang, I jumped up simply because I suddenly remembered that my behind needs cleaning!”

For the curious For the curious

Unlike dogs, when cats “wag” their tails, it does not signify a friendly attitude. It’s usually a sign that the animal is feeling conflicted.

Subtle movements of the tail tip can suggest extreme tension. Often seen when a cat is stalking its pray and is unsure if it should pounce now or in a moment. Rapid banging of the tail against a cat’s sides is usually a sign of anger and a hesitation between attack and escape.

You can imagine that when a dog sees these tail movements as an invitation to play, things might get ugly real quick. The legendary animosity between cats and dogs often comes down to a simple misunderstanding

THE PARAMECIUM

THE PARAMECIUM

How to live… sans butt?

The butt, the bum, the rump, the backside… however you call it, we’ve all got one. You’d have to be a real simpleton not to use it. And yet there live in this world just such organisms – simple and primeval… or rather protozoan. Protozoans are very old creatures, not quite plants and not quite animals.

Protozoans inhabit their own kingdom, which spans our entire world. Although they’re pretty much everywhere, we only see them under the microscope.

One of the most famous protozoans is the paramecium. Its polish name (“pantofelek” which means “slipper”) stems from the fact that it is shaped somewhat like a shoe, albeit a really, really small one, as paramecia are only one third of a millimetre long.

The paramecium, like all protozoans, consists of only one cell, which must perform all the functions for which a human body requires several hundred million! Its favourite dish are bacteria. After a meal, undigested leftovers make their way to the paramecium’s butt, called the cytopyge. Well… it’s not really a butt, but the closest thing the paramecium has to one.

The cytopyge is surrounded by tiny cilia just like the rest of the paramecium’s cell. An interesting question: do you think that when paramecia fight, they tell one another “Scram, or I’ll kick you in the cytopyge”?

For the curious

A paramecium doesn’t ever die of old age. It just splits into two new paramecia, which in time split again and so on. That means that – while it constantly changes – the very first paramecium never actually perished.

Though it’s older than the dinosaurs, we shouldn’t really consider it simple. Far from it. It’s just that the paramecium already found a terrific way of life millions of years ago. While other animals continue to evolve, it stays the same – and is still going strong. Who’s the simpleton now, eh?

THE WEAVER

THE WEAVER

Entangled in courtship

A bird’s butt, including the tail and cloaca (or bird butthole) is called a rump. Though the word itself might not sound pretty, many rumps themselves are very dignified. Roosters come to mind, as well as pheasants or peacocks, but some species are even more ornamented.

There are birds living in Africa that weave exceptionally beautiful nests out of grass and twigs. That’s where they get their name from – weavers. They aren’t particularly large, but the biggest of their family is called the longtailed widowbird.

As the name suggests, the bird itself isn’t all that huge (it’s a tad smaller than a pigeon, actually), but it has a truly impressive tail!

The females of the species are grey and inconspicuous, whereas their male counterparts look all dark and shiny and have exquisite, impressive tail feathers up to half a metre long. When they want to impress the females, they fly slowly just over the grasslands and spread their tails wide like elegant black overcoats.

Please purchase the full version of this book