Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

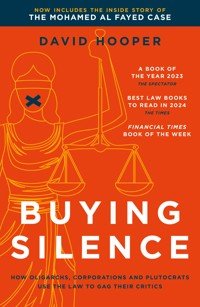

This timely and important book focuses on the controversial issue of SLAPP cases – Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation – which are designed to censor, intimidate and silence critics by burdening them with aggressive opposing lawyers, heavy legal costs and enquiry agents until they abandon the case. David Hooper, veteran media lawyer, explores how the power of money enabled the very wealthy to crush their critics and outlines the tactics they used. He examines how billionaire oligarchs, often ex-convicts and linked to organised crime, have tried to launder their reputation in this country by suing for libel, and how they have found lawyers only too happy to pocket their roubles. Hooper describes his experience with some of these oligarchs, including Boris Berezovsky when Hooper needed an armed bodyguard while collecting evidence in Moscow. It was a case where both plaintiffs were ultimately murdered, as was his client, the editor of Forbes Russia. The UK also has its home-grown Slappsters, of whom Nadhim Zahawi and Mohamed Amersi are the most recent examples. They also come from Greece, Sweden, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Malta and the United States. Hooper describes how those with something to hide tried, with varying degrees of success, to stop you knowing about it, and how their lawyers were willing to help them. The well-paid legal profession does not emerge with credit.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 611

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

iA BOOK OF THE YEAR 2023, THE SPECTATOR

BEST LAW BOOKS TO READ IN 2024, THE TIMES

FINANCIAL TIMES BOOK OF THE WEEK

“A terrific look by very distinguished lawyer at the way the rich and powerful can use the law against their critics and crush them with huge legal costs … A shocking and vitally important book.”baroness helena kennedy of the shaws kc

“As an outstanding libel lawyer, David Hooper’s masterful investigation is a terrifying expose of Britain’s corrupt judicial system.”tom bower, author of maxwell: the outsider

“This is a vital book on how the rich use the courts and the legal profession to muzzle news organisations when it comes to the disclosure of their nefarious deeds.”graydon carter, founder of air mail and former editor of vanity fair

“A detailed and shocking account by an experienced media lawyer of the scandal of SLAPP actions and the need for fundamental reforms of the law and the legal profession.”sir david davis mp

“Compellingly told, eye-popping, sometimes hilarious and always illuminating … Buying Silence is an urgent call to arms, exposing why the British tradition of ‘free speech’ is increasingly a myth.”mark stephens cbe, solicitor

ii“This book is a beacon of enlightenment, offering hope and solutions against legal bullying. A must-read for advocates of free speech.”eliot higgins, journalist and founder of bellingcat

“Hooper … is succinct, yet still includes the telling detail of someone who has been unnervingly close to the action … What Buying Silence captures especially well is the sheer gall of the age of ‘alternative facts’ in which those who have a surfeit of money are enabled by the legal system in their bids to re-landscape the truth.”laura slattery, irish times

“Terrific … It is the most extraordinary thing for an ordinary British citizen to read how it is that English law has become this system of menace around the world … A very timely book.”nick cohen, the lowdown

“A powerful and compelling book. Hooper has been at the forefront of media law and involved in many of the power battles he recounts … He pulls no punches with his own profession.”frances gibb, the times

“David Hooper, now retired from practice as a media lawyer, but who has certainly not lost his touch for adventure, has written a good book about some bad people.”lord garnier kc, inforrm

“Hooper is a witty writer and this is not a dry legal textbook. The detail is entertaining, absurdist and sobering. Some of it could be described as Monty Python enters Kafka’s The Trial.”tim crook, the journal

iii

iv

v

To my wife Caroline, with my heartfelt thanks for all her assistance in the years of researching and writing this book.

vi

Contents

Introduction

By June 2020, after nearly fifty years in the law, I had retired to the Brecon Beacons. It was time to cultivate the garden and enjoy the Welsh sunshine while coping with lockdown. Emerging from a particularly challenging flowerbed, I found a journalist from Thomson Reuters was calling from the US. Why, he asked, was Hooper the name that they had come across most often as they researched the hacking of thousands of individuals that had taken place in 2015 and 2016?

I had my suspicions and suggested that Thomson Reuters check whether the Greek clients for whom I had been acting in a recent libel action had also been victims. A few days later, Thomson Reuters confirmed they too had been extensively hacked. We now knew where to start investigating.

Thomson Reuters, together with the Citizen Lab, an independent internet research group affiliated to the University of Toronto, had been investigating a group which they named Dark Basin, a hacking-for-hire company in India. They had linked Dark Basin to BellTroX, an Indian cyber firm. Between 2013 and 2020, BellTroX had made 80,000 attempts to hack into email accounts, successfully spying on 13,000 of them, and had tried to break into the inboxes of 1,000 attorneys at 108 law firms around the world. Thomson Reuters had uncovered thirty-five court cases in which one side tried to purloin documents and privileged information from the xiiother, using password-stealing emails. There had been attempts to compromise eighty accounts at a leading Paris-based law firm Bredin Prat. It was, the journalist told me, one of the largest spying-for-hire operations ever exposed.

BellTroX had initially been employed by big businesses – oil companies, for instance – to spy on environmental campaigners, journalists and political opponents and had now broken into the communication systems of opposing lawyers and their clients, targeting and hacking them with spear-phishing emails and bogus Facebook and LinkedIn messages. BellTroX had also been hired to spy on the Financial Times journalists exposing the multi-billion fraud at Wirecard, the German payment processing company. The name ExxonMobil appeared in press articles as having been a BellTroX customer, although Citizen Lab did not have any evidence the company commissioned the hacking. A spokesman for the company said it had no knowledge of or involvement in the hacking activities outlined. However, as discussed later in the book, further investigations have revealed the extent of the hacking. This has produced further anguished denials by Exxon of any involvement in the hacking. It underlines the denial of accountability for the actions of well-remunerated private investigators.

Thomson Reuters’s call led me to investigate BellTroX and how their Dark Basin network operated. They did not come cheap. Along with another Indian outfit called CyberRoot, they had billed $1,000,000 for their nefarious services when hired by a sovereign wealth fund called the Ras Al Khaimah Investment Authority (RAKIA). I discovered that BellTroX had been hired by RAKIA to hack an American Iranian businessman, on occasion even sending his employees the same phishing emails that were being sent to me. This hacking operation set in motion a series of cases in both this country and the US, involving allegations against a large international law firm of perjury, perverting the course of xiiijustice, hacking opposing lawyers and their bank accounts, betrayal of trust and gross overcharging. All this together with the same law firm’s alleged involvement in the brutal interrogation of leading lawyers in the UAE, who had been held in solitary confinement after their illegal rendition from another state – allegations described by a High Court judge as probably the most serious ever raised against a law firm. I will go on to examine whether these are purely isolated incidents or whether they reveal a deeper problem.

BellTroX’s activities had not gone unnoticed. In 2019, the FBI had arrested, amongst others, Aviram Azari, an Israeli private investigator, as he holidayed in Florida. They seized his phones and laptop (an invaluable guide to his hacking) which revealed that BellTroX had got hold of my password. In April 2022, Azari pleaded guilty to computer hacking, conspiracy to commit wire fraud and aggravated identity theft. He had already been imprisoned for four years when in November 2023 he was sentenced to eighty months. The FBI are currently seeking the extradition of another Israeli private investigator and alleged hacking confederates of Azari, Amit Forlit, from London to the US.

Such activity is extremely difficult to detect. The chain of private investigators, of varying respectability, is only likely to be exposed by one of their own, or if a disclosure order can force a bank to reveal the identity of the ultimate paymaster. Happily, both eventualities occurred in the RAKIA case, and the downfall of BellTroX was further hastened by their employees in India settling scores for the yawning gap between the pittance ($370 a month) they earned and the exorbitant fees charged by their employers. A shocking picture of legal greed and a willingness to win at all costs emerged. I discovered that the hackers in that case were at the same time sending identical phishing emails to me.

I am not suggesting that the opposing lawyers in the Greek libel case that had precipitated my inquiries were involved in the xivhacking. There is no evidence that they knew of the hacking or behaved improperly. But the widespread use of hacking underlines the pressing need to safeguard the integrity of litigation and the rule of law. It led me to investigate how widespread and insidious the practice is, and I found there is a need for tight regulatory control of solicitors when they use private investigators. I will describe what it is like being hacked, how the hackers operate, and what happens to them when they are convicted in the US. I will examine what steps could be taken to deal with the increasing problem of hacking. For my own part, as I explain in my account of the Mionis case in Athens which involved my Greek clients, I later found myself on the receiving end of a SLAPP action in Greece. Mionis sued me for €300,000 for libel, in respect of the evidence I had given to a judge in the Greek Supreme Court. Charges of criminal libel and perjury were thrown in, which appear to carry a total of three years’ imprisonment. I am hoping he will be as unsuccessful as Mohamed Al Fayed, who was the last person who wanted to prosecute me.

The abuse of libel laws by oligarchs, corporations and plutocrats to suppress adverse publicity and criticism is on the increase. Sanctions may provide a temporary respite, but the underlying problems remain. Legal fees in excess of £1,000 an hour are not unusual, and this encourages armies of lawyers to feed at the trough. Countermeasures such as Unexplained Wealth Orders, designed to confiscate ill-gotten assets, tend to be seen off by oligarchs, who hire the sharpest and most expensive lawyers to do battle with underfunded and under-resourced government agencies. Their London property and investment portfolios and superyachts, held through a network of offshore companies, remain largely unscathed and, where possible, have been moved to accommodating jurisdictions such as Dubai and Cyprus. PR advisers assist in reputational and political laundering, including charitable and political donations. Some of xvthese wealthy claimants, and their lawyers and private investigators, are willing to use aggressive and intimidatory tactics that are simply not acceptable, designed to shut opponents up rather than to seek a genuine remedy. There has been a significant increase in the willingness of law firms to condone illegal hacking and to sacrifice ethics on the altar of vast fees from questionable sources.

Some law firms tout various additional skills in cyber and personal security. The website of one leading firm boasts intelligence experts, investigative journalists and senior figures from the military and police on its payroll. It now proposes to diversify into public relations. That bristles with difficulties. Would they be acting as solicitors, or PR consultants or both at the same time? Would the PR activities be regulated by the Solicitors Regulation Authority (SRA)? Would the lawyers be claiming that their PR communications were covered by legal privilege? Yet another law firm boasts cyber and investigation specialists working alongside their legal teams.

It is a far cry from the small but perfectly formed outfits previously clustered around Lincoln’s Inn, which made do with aggrieved letters of complaint on behalf of their clients. Solicitors previously renowned for defending media companies against libel claims have found the lure of the rouble and the demands of their paymasters difficult to resist. Since many of these oligarchs had obtained their wealth by criminal means and had successfully avoided the taxman, they had plenty of cash to throw at lawyers, sometimes with unlimited budgets. This is now the era of the SLAPP action – to use the American acronym – Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation. SLAPP actions, as the government noted in its fact sheet for the Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Bill 2022, fundamentally undermine freedom of speech and the rule of law. They are actions aimed at muzzling opposition, rather than resolving any genuine legal grievance, designed to silence xvicriticism and to evade public scrutiny. They tend to be brought by wealthy individuals or corporations against weaker opponents and use unduly aggressive or costly tactics. The era of win at all costs, whether legal or illegal, is upon us.

Where did this all start? Corporations – Nomura, Upjohn and McDonald’s, to name but a few – found libel proceedings (a number of which I was hired in to fight off their egregious claims) to be such a good way of silencing their critics that it became an adjunct to their public relations strategy. Plutocrats – the Goldsmiths, Maxwells, Al Fayeds and Aga Khans of this world – got in on the act, closely followed by Boris Berezovsky, a man with close links to organised crime and a past so bloodstained I needed an armed bodyguard while defending his libel action. Our client, Paul Klebnikov, the American editor of Forbes Russia, was shot by gunmen in Moscow acting on the orders of Berezovsky. Many of Berezovsky’s fellow oligarchs soon followed suit, pursuing libel claims as a way of silencing their critics. The dangers of SLAPP actions are very graphically illustrated by the Al Fayed case, where I defended his claim against Vanity Fair. As I describe in detail, we uncovered the enormity of his crimes, though worse were to follow. However, he was able to cover up his crimes and those of his brother Salah for the next twenty-seven years until his death. There must be a full inquiry into his sexual offences, his corruption of the police, his ability to suppress the truth, the activities of his enablers and the failure of the General Medical Council (GMC) to investigate the doctors who worked for Fayed.

Grigori Loutchansky was an early Russian libel litigant with, like a surprisingly large number of them, a criminal record. Released from a Latvian jail, he made his fortune from arms dealing and was described by Time magazine as ‘the most pernicious unindicted criminal in the world’. Despite being barred from the UK, and notwithstanding his colourful CV, he won his libel actions xviiagainst The Times in London for the allegations that he was an organised crime boss.

Gafur Rakhimov was another with a less than spotless background. A leading figure in the world of Olympic boxing, he had been banned from the Sydney Olympics in 2000 because of his alleged links with organised crime. He was sanctioned by the US Treasury in 2017 as a leading member of an Uzbek crime syndicate, Thieves-in-Law. Ultimately, even the leading London libel law firm Carter-Ruck struggled to salvage his reputation and have him removed from the US sanctions list, although they will have made a good living over the years in their efforts to do so.

Since these early SLAPP cases, there have been a string of libel actions brought by Russian or former Soviet state oligarchs and their companies and organisations. Their opponents include: Christopher Steele, formerly of MI6; The Economist; Craig Murray, the former British ambassador to Uzbekistan; Eliot Higgins of Bellingcat; Catherine Belton, the author of Putin’s People, and her publishers, HarperCollins; Tom Burgis, the author of Kleptopia:How Dirty Money is Conquering the World; the Financial Times; and Paul Radu, a Romanian investigative journalist and the co-founder and director of the Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Network. A case recently before the English courts and described in Chapter 16, relating to former President of Kazakhstan Nursultan Nazarbayev, suggests that SLAPP actions still arise. In that case, an obscure London-based company named Jusan Technologies Ltd sued The Telegraph, openDemocracy, the Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project and The Bureau of Investigative Journalism.

The claims brought successfully by the millionaire founder of Leave.EU, Arron Banks, against Carole Cadwalladr for her TED Talk and her tweets; or the claims brought unsuccessfully by Mohamed Amersi, a multi-millionaire donor to the Conservative xviiiParty, against a former MP, Charlotte Leslie, and the BBC; or those brought in England by a Swedish businessman living in Monaco against a Swedish online publication; or by Christopher Odey against the Financial Times; or by Dale Vince against assorted ‘right-wing nuts’ show that the problem has not disappeared with the sanctioning of some oligarchs. Ignatova Ruja, the Cryptoqueen of the OneCoin fraud, used SLAPPS to help her continue to deceive and steal billions from unsuspecting investors. SLAPPs do not just involve claims by billionaires. They can be used against those seeking to expose sexual or domestic abuse or those who post unfavourable reviews on websites.

Law firms should no longer be able to accept their instructions unquestioningly, on the basis that everyone is entitled to their day in court. Given the enormous cost of libel actions and the burden of proof being on defendants, it is crucial that lawyers check the underlying facts and do not bring hopeless or absurdly overstated cases on behalf of their clients. For example, it is highly questionable whether it was right for Yevgeny Prigozhin to be able to bring clearly false libel claims against his opponent, Eliot Higgins of Bellingcat. Prigozhin sued Higgins over claims that he was involved with the Wagner Mercenary Group and the trolling organisation Internet Research Agency. Prigozhin admitted his links with both organisations very shortly afterwards, to no one’s surprise. Law firms taking on libel cases also need to review rigorously where their funding is coming from. Take, for example, the case of a Russian policeman who was mysteriously able to spend a seven-figure sum on a hopeless English libel action against Bill Browder, despite ostensibly having almost no money to his name.

It is not just the claims brought before the courts which give rise to concern. It is the threat and the cost of such proceedings which are alarming. Of course, people should have access to the courts and be able to bring legitimate claims. However, on examination, xixone finds that it is the powerful and wealthy, backed by their lawyers, public relations consultants and private investigators, who are the ones who have access to justice. Increasingly, public relations consultants are being given an aggressive role of seeking to blacken the reputation of the opposing party. Private investigators are likewise being used to undermine and intimidate opponents with no questions being asked as to the legality of their methods. With the growth of AI, the ability to fake documents is another potential weapon in litigation. It is too difficult and costly for the average citizen to bring their legitimate claims to court. The cost of doing so in the UK is a large multiple of what it would cost in continental Europe. Additionally, where unmeritorious claims are brought, the question of whether they should be allowed to proceed should be assessed by the court itself at the very outset, before hundreds of thousands of pounds have been spent in legal costs responding to the claim.

Libel claims should not be the exclusive preserve of the extremely wealthy and those who have access to top law firms, whose level of fees are increasingly described as eye-wateringly high. Law firms must start, where appropriate, justifying unduly aggressive tactics, disproportionately expensive litigation and, on occasion, why they are acting at all. The SRA should start imposing the level of fines for solicitors that are imposed in other sectors. Courts should be willing to order law firms to reimburse legal fees if their behaviour has been particularly egregious.

The Conservative government appreciated the problem of SLAPP actions and produced the first piece of legislation to deal with such cases. As I explain later, the existing legislation is not sufficient. Proposed reforms in Wayne David’s private member’s bill failed with the calling of the July 2024 general election. The Labour government has committed itself to a wide-ranging Anti-SLAPPs Act but still has to put forward concrete proposals. The argument xxof this book is that the changes can be quite simple. At the centre of the legislation should be an expanded concept of what kind of information is in the public interest. It is also crucial that we legislate against allowing every allegation which could arguably be said to be defamatory to proceed to trial. The courts should balance the public’s right to receive information on a matter of public interest and the writer’s right to freedom of speech against the need of the complainant to bring the claim and the damage that would be likely to be caused to their reputation or privacy.

We live in an age where there is much greater scope for sharply divergent opinions, particularly on social media. Those in the public eye should be able to absorb a certain amount of adverse publicity without always reaching for their libel lawyer. The ever-increasing cost of litigation and the financial pressures on traditional media outlets as they lose advertising revenue to online outlets mean that, often, controversial issues are not getting published, and the temptation is for media outlets to back down in the face of legal threats from the powerful and wealthy.

We also live in an age where institutions are only too ready to suppress the truth and silence their critics, whether it be the government in the Spycatcher saga, the Post Office in their persecution of sub-postmasters, the National Health Service in the infected blood scandal or the South Yorkshire Police in the Hillsborough Stadium disaster. All too often they are assisted by lawyers whose integrity is sold out to a desire to win at all costs.

In the pages that follow, I suggest what needs to be done.

Part I

Where Did It All Begin? The Early SLAPP Actions2

Chapter 1

Sir James Goldsmith: Goldenballs Sets SLAPPs Rolling

The financier and entrepreneur Sir James Goldsmith was one of the first to show how the law of libel could be used to crush your opponents. Ultimately, his attempts failed, but it was not for want of trying. He was only unsuccessful because of the dogged resistance and resilience of Private Eye.

No one at that stage had heard of SLAPPs, but in what was probably the first SLAPP action, Goldsmith used his financial power to invoke the virtually moribund Libel Act 1843, which carried a sentence of up to two years in prison. It had scarcely been used since the 1920s. In 1923, Lord Alfred Douglas, Oscar Wilde’s former boyfriend, had been jailed for six months for accusing Winston Churchill of conspiring with the financier Sir Ernest Cassel to make money on the New York stock market by issuing false communiqués about the outcome of the Battle of Jutland during the First World War.

By 1975, criminal libel was considered more or less extinct. However, this would change when, in December 1975, Private Eye published an article named ‘All’s well that ends Elwes’ by Patrick Marnham. The piece was published following the suicide of the artist Dominic Elwes, who had been accused of betraying his friends by passing details of a lunch organised by Goldsmith at the Clermont 4Club to the Sunday Times journalist James Fox. The article alleged that at the lunch, Lord Lucan’s friends had met to discuss what plans they should make to deal with the fact that Lord Lucan had murdered his children’s nanny, having mistaken her for his wife, and to what extent they should help him in his flight from the police. After two further articles in Private Eye suggesting Goldsmith was unsuitable to be chairman of the industrial conglomerate Slater Walker and that he had links to the politician T. Dan Smith, who had been jailed for corruption, Goldsmith decided he would put the ‘maggots and scavengers’ at Private Eye out of business.

His obsessive and no-holds-barred attempts to do so over the next eighteen months are fully described in Richard Ingrams’s book Goldenballs. The editor, the publisher and the principal distributor of Private Eye were sued, as were thirty-seven wholesale and retail distributors of the magazine – seventy-four writs initially – a figure which would soon climb to ninety. There were ten separate court hearings, two unsuccessful attempts to get Ingrams imprisoned for contempt and one equally unsuccessful effort to get the assets of Private Eye sequestrated. The case cost Goldsmith £250,000 and Private Eye £85,000.

Goldsmith had persuaded Mr Justice Wien to give permission, as was required under the Law of Libel Amendment Act 1888, to bring proceedings for criminal libel against Private Eye, as well as against Ingrams as editor, Marnham as author, Pressdram as publishers and Moore-Harness as distributors. Additionally, notwithstanding the dissent of Lord Denning, the Court of Appeal ruled it was not in fact an abuse of process to sue all the distributors of Private Eye for libel – thereby opening the door to future SLAPP actions. However, Lord Denning was ahead of his time and he had spotted what came to be known two decades later as SLAPPs in Goldsmith’s tactics of bringing a criminal libel case and suing the distributors of Private Eye. 5

In a civilised society, legal process is the machinery for keeping and doing justice. It can be used properly or it can be abused. It is used properly when it is invoked for the vindication of men’s rights or the enforcement of just claims. It is abused when it is diverted from its true course so as to serve extortion or oppression: or to exert pressure so as to achieve an improper end … If it can be shown that a litigant is pursuing an ulterior purpose unrelated to the subject matter of the litigation and that, but for his ulterior purpose, he would not have commenced proceedings at all, that is an abuse of process.

Eventually, on 16 May 1977, the litigation was settled at the doors of Court No. 1 of the Central Criminal Court. No evidence was offered on the criminal libel charges, but Private Eye agreed to pay £30,000 towards Goldsmith’s legal costs over ten years and to publish a full-page advertisement containing their less than heartfelt apology in the Evening Standard.

In theory, Goldsmith had achieved some success, but it was at considerable cost to his reputation. The general feeling was that Goldsmith had severely overdone things. He was referred to in Private Eye thereafter as ‘Goldenballs’ or worse, and the magazine managed to raise £40,000 towards its legal costs through its ‘Goldenballs’ appeal. Private Eye further exacted some revenge by mocking his recently established news magazine, Now!, out of existence.

However, Goldsmith had laid down a benchmark for future SLAPPsters as to what the very wealthy could potentially achieve in the libel courts. The case also ensured that the media were extremely circumspect in what they published about his business, political and personal life until his death, despite his controversial role in establishing the Referendum Party. There were virtually no more criminal libel cases, and the crime was eventually abolished by the Coroners and Justice Act 2009. Not only did Goldsmith show how 6the law of libel could be used to muzzle the press, he even set up the Goldsmith Foundation – with the not entirely disinterested advice of none other than Peter Carter-Ruck – to offer financial assistance to those who he was satisfied had been libelled.

Chapter 2

Robert Maxwell: A Crook’s Manual to SLAPP Actions

Robert Maxwell had a simple solution for those wanting to investigate his businesses and his background: he would call in the lawyers and shower his critics with writs. With the help of his lawyers, he devised a number of the legal weapons that were to be used with increasing frequency over the succeeding decades, including the weaponisation of data protection laws and the practice of suing booksellers for libel in response to negative press stories about him.

The way that Maxwell conducted his business affairs had been the subject of severe criticism by Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) inspectors Owen Stable QC and Ronald Leach, who in 1971 reported that he was ‘not in our opinion a person who can be relied on to exercise proper stewardship of a publicly quoted company’. The Sunday Times wrote a series of articles about his business malpractices in response to the report, and Maxwell duly issued five writs against them. When it became apparent that they would fight the cases in court, he dropped the actions.

While large newspapers were able to stand up to Maxwell’s bullying tactics, book publishers and the remainder of the press, particularly local newspapers, became distinctly nervous about what they wrote about Maxwell. The criticisms made by the DTI 8inspectors receded into the distance. Merchant banks and lawyers were soon happy to pocket his money again.

Maxwell fired off writs at all and sundry. He sued his Conservative opponent Sir Frank Markham in the 1959 general election. He even bullied an apology out of the benign character actor Robert Morley for his perceptive comments regarding Maxwell’s financial shenanigans on the BBC Radio 4 show Any Questions? in 1969. Local papers regularly had to apologise to Maxwell and make payments to charity, which he was not slow to publicise. He regularly sued Private Eye, with a reasonable degree of success. In 1984, he became the owner of Mirror Group Newspapers, which thus became the Maxwell house journal, writing fawningly about him as a leading world statesman and businessman.

In the end, his bombastic nature got the better of him. He had to capitulate when he sued The Bookseller for its coverage of an industrial dispute at Pergamon Press. Maxwell ludicrously complained that the article damaged his reputation as a trade unionist – despite his existing notoriety for his peremptory sacking of employees. We had discovered that Maxwell, the worthy trade unionist, used to lie to industrial tribunals about being abroad on urgent business, so as to run up the claimant’s legal costs by obtaining adjournments. On the second such occasion, photographs were obtained of Maxwell’s Rolls-Royce parked outside Maxwell House, ready to ferry the liar to a dinner in Oxford. Having been tipped off that the one barrister who the bullying Maxwell feared was the Sunday Times’s counsel, John Wilmers QC, we retained him. Maxwell had got nowhere when he called David Whitaker, the editor of The Bookseller, complaining that he was fed up with being libelled by The Bookseller and threatening dire consequences if they did not back down. ‘Balls,’ said Whitaker, rather succinctly. After more bluster, Maxwell capitulated, not relishing the prospect of being cross-examined by Wilmers, and paid The Bookseller’s costs 9in full. Years later, I met Maxwell, who told me he had been told by his lawyers to settle but regretted doing so. I told him that they had given good advice.

In 1987, Maxwell discovered that two unauthorised biographies were due to be published about him. He turned to Lord Mishcon, distinguished creator of the law firm Mishcon de Reya, for advice as to how he could stop the books. Over the next four years, Maxwell resorted to an astonishing array of SLAPP tactics. His lawyers found a libel in the first book, Maxwell: A Portrait of Power by Peter Thompson and Anthony Delano. The book was pulped and republished with the offending passage removed. Determined to win, Maxwell proceeded to successfully sue over the blurb on the paperback. That killed off the book.

However, he met his match in his attempts to suppress Tom Bower’s Maxwell: The Outsider. By this stage, Maxwell had commissioned Joe Haines, assistant editor at the Daily Mirror, to write a hagiography of Haines’s employer entitled Maxwell, in order to pre-empt Bower’s book. Bower, Aurum Press (the publishers) and my law firm, Biddle & Co., were by then ready to defend Maxwell’s onslaught. The book was typeset in Singapore, printed in Finland and stored at a secret location in the UK. If the burglars who broke into the offices of Aurum Press hoped to find a copy, they were to be disappointed. Nevertheless, on 23 February 1988, three weeks before publication, Maxwell issued the first of twelve writs for libel and breach of confidence against the book.

Maxwell had not seen or read Bower’s book, but a detail like that was not going to stop him. He tried unsuccessfully to obtain an injunction to prevent publication of the book, but Mr Justice Michael Davies was having none of that. Maxwell tried to persuade Rupert Murdoch and Andrew Neil, editor of the Sunday Times, not to serialise the book but again without success.

Unknown to us at the time, Maxwell resorted to even more 10dubious means, assisted by a motley bunch of private investigators. Maxwell’s ‘Bower File’, which found its way to Bower after the collapse of the crook’s empire, revealed the extent of the surveillance of Bower’s home and the tracking of his whereabouts and his personal finances. His Hampstead house ‘looked to be tastefully and expensively decorated inside’, the sleuth reported. More sinister, however, were the attempts to lay hands on the draft of the book stored on Bower’s computer at home.

The rationalisation for these manoeuvres was Maxwell’s unjustifiable claim that Bower had unlawfully stored personal data about Maxwell on his computer in his office at home. He took counsel’s advice as to whether Bower could be reported to the Director of Public Prosecutions for failing to register as a data user under the Data Protection Act 1984. Having failed to obtain support for this optimistic course of action from his barrister, Stephen Nathan – who pointed out the small detail that Maxwell had no evidence to support his claim – Maxwell next tried the civil remedy known as an Anton Piller order, which would enable his lawyers to seize Bower’s computer and obtain a warrant to search his home without any warning. However, Maxwell needed evidence of serious wrongdoing by Bower to enable him to obtain such a draconian remedy, which, of course, he did not have. Maxwell persisted, despite this discouraging legal advice, but this meant he had to get hold, by hook or by crook – and it was more by crook than hook – of the contents of Bower’s computer.

Peter Jay, Maxwell’s chief of staff, sought the assistance of Control Risks, a leading corporate investigator, who quoted the sizeable fee of £50,000 (£155,900 in 2024 values) for a plan which involved sneaking a van containing a scanner into the Post Office depot at the end of Bower’s garden to lift the offending material off Bower’s computer – an ambitious project given the state of 1988 technology. Jay accepted that the plan was ‘not really practical’, based not on 11the illegality of the enterprise but on the advice of Control Risks that the required evidence ‘could not be obtained with our existing equipment’ and that it was uncertain whether the costly and sophisticated equipment needed would ‘overcome the technical problems’ due to the ‘levels of background radiation’. Maxwell’s attempt to seize Bower’s computer material was an early abuse of data protection laws by those who conduct SLAPP litigation. Before the advent of computers, it would have been inconceivable that any legal team could have contemplated entering Bower’s property without his knowledge or a court order and helping themselves to a copy of his working documents. It was the top of a slippery slope.

Maxwell’s next step was to get Mishcon de Reya to threaten legal action against booksellers if they sold the book. Most decided it was prudent to avoid carrying the book and those that did, such as Hatchards, were sued. Mishcon de Reya did not break any laws while representing Maxwell, nor did they breach the contemporary rules of conduct for solicitors. But they did, in large measure, provide a launchpad and inspiration for future SLAPP actions with their innovative use of data protection claims and legal actions against booksellers. Bower’s book was a bestseller after its serialisation in the Sunday Times, and the first edition sold out. But Maxwell’s tactics nevertheless had some success in those pre-Amazon days, as booksellers were nervous of stocking the book in view of Maxwell’s threats and the Booksellers Association’s advice to their members to be cautious. The publishers had to offer the braver ones an indemnity against being sued in order for them to stock the book.

Maxwell went even further by suing Bower for defamation and invasion of privacy in France, but the case was thrown out and Maxwell was ordered to pay costs of 10,000 francs (£1,020). The French judge was unimpressed by the disrespect for privacy shown 12by Maxwell’s papers after they published pictures of the young Prince William and Prince Harry having a quiet pee. In addition to the twelve lawyers and assorted private detectives Maxwell had engaged to prevent the publication of Bower’s book, he even resorted to buying the publishers who were due to publish the paperback of Maxwell: The Outsider. They got around the issue by reverting the paperback rights to Bower before the sale went through.

Maxwell also sued the BBC over an article in their magazine, The Listener, about Bower’s book. In April 1991, Maxwell issued a further writ against Bower personally for a profile he had written in the American magazine New Republic, which had a paltry circulation of 136 in England.

On 5 November 1991, Maxwell fell off his yacht, the Lady Ghislaine, and was found dead in the water. His hopes that devoting ever-larger sums of money to his libel cases would cajole Bower and his publishers into settling would never come to fruition. Likewise, Maxwell’s libel claim against the publishers Faber and Faber over The Samson Option by Seymour Hersh came to an abrupt end upon his death. The old rogue was buried on the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem, amidst praise from the President of Israel and much to the grief of libel lawyers.

The last vestiges of Maxwell’s reputation disappeared when, in 1995, Bower published a 455-page book, Maxwell: The Final Verdict. In the book, Bower explained in detail how Maxwell had engaged in a massive fraud to prop up Mirror Group share prices and how he had stolen hundreds of millions of pounds from the Mirror pension fund – leaving his sons Kevin and Ian bankrupt and facing prosecution for fraud. They were acquitted after a lengthy trial.

Maxwell’s frauds, his looting of the Mirror pension fund and the exposure of his close links with the Soviet Union were the criminality and duplicitous behaviour that Maxwell, by his industrial-scale litigation and dirty tricks, had tried to suppress. His aim 13was not vindication of reputation but the suppression of the truth and the prevention of the public discovering information about his frauds. On his death he lost that battle, but his legal tactics were to be emulated by a succession of equally unsavoury plaintiffs.

With their expertise in litigation, Mishcon de Reya became the go-to firm for the legal problems of those termed ‘politically exposed persons’. These include oligarchs and leaders in politically insalubrious areas of the world who have been deemed (rightly or wrongly) under money laundering regulations to be more susceptible to involvement in bribery or corruption through their prominence or position of influence in their countries. Mishcon de Reya’s managing partner Kevin Gold indicated in a 2014 interview that the firm had made it its business to deal with politically exposed persons. With commendable foresight, Gold stated that ‘people who were friends of Britain can become untouchables in a very quick time’. The firm has attracted some controversy following remarks made by MPs under cover of parliamentary privilege about how it has represented of some of its clients in Malta. Their representation of controversial figures such as Mikhail Nadel (Kyrgyzstan), Taib Mahmud (Sarawak), Beny Steinmetz (Guinea) and the Aliyev family (Azerbaijan) has been noted by organisations such as Global Witness.14

Chapter 3

Mohamed Al Fayed: Lies Were the Truth and the Truth Was a Lie

One of the earliest exponents of the practice of using libel laws to silence his critics and control publicity about himself and his business operations was Mohamed Al Fayed, long-time owner of Harrods. In order to be able to buy Harrods – using the money of the Sultan of Brunei – Fayed repeatedly lied about his origins, his commercial background and sources of wealth. He upgraded his surname to Al Fayed from plain Fayed, to give himself added credibility. He had led a colourful life posing as Sheikh Mohamed Fayed, boasting connections to the Kuwaiti royal family and offering to construct port and oil refinery facilities in Haiti before fleeing in February 1965 accused of fraud and with a contract on his head from Papa Doc Duvalier. He later made false claims about his role in the development of Dubai.

His use of libel laws attracted strong criticism from Department of Trade (DTI) inspectors Henry Brooke QC and Hugh Aldous, who stated in their report:

A rather sinister aspect of the evidence before us had been a constant and unprincipled process of gagging the press … Fayed was telling lies about himself and his family … he gave instructions to his very able lawyers to take legal action against anyone 16who sought to challenge his claim that he and his brothers beneficially owned the money with which they had bought HOF [the department store House of Fraser] … As a result of what happened the lies of Mohamed Fayed and his success in ‘gagging’ the press created a new fact: that lies were the truth and the truth was a lie.

A precursor of Donald Trump’s ‘alternative facts’, one could say.

The inspectors, who had investigated the circumstances in which Fayed acquired House of Fraser and Harrods, further stated, ‘The Fayeds dishonestly misrepresented their origins, their wealth, their business interests and their resources to the Secretary of State … the press, the HOF Board and HOF shareholders, and their own advisers.’ They concluded that he had lied to the inspectors.

One of Fayed’s targets was The Observer, which had been acquired by his rival bidder for the House of Fraser, Tiny Rowland. The newspaper had published nine articles between October 1985 and May 1986 about his background, including how he had added the ‘Al’ prefix to his name and how he had obtained the money to buy Harrods from the Sultan of Brunei. Eventually, Fayed dropped his libel claims and paid The Observer’s £500,000 legal costs. By his aggressive libel tactics, Fayed had been able to restrict what the press said about him and ensured that the findings of the DTI inspectors – namely that he had been ‘deceitful and dishonest in his acquisition of the House of Fraser’ – receded from public memory.

Fayed didn’t stop there, suing the Financial Times, the Far Eastern Economic Review and the Institutional Investor. In 1989, he persuaded Century Hutchinson to pulp a book by Steven Martindale, a Washington lawyer, about his relationship with the Sultan of Brunei, By Hook or By Crook. Fayed was paying libel lawyers to suppress the truth.

When Fayed failed to persuade the European Court of Human 17Rights that he had been deprived of the right to a fair public hearing by the DTI inspectors, he dismissed the judges as ‘thirteen old farts’. He resorted to spreading lies about one of the DTI inspectors, falsely claiming to have compromising photographs of him. Adnan Khashoggi, Fayed’s brother-in-law, had described him as an unbelievable criminal and liar.

In September 1995, Vanity Fair published a profile of Fayed by Maureen Orth titled ‘Holy War at Harrods’. Originally they had envisaged a reasonably sympathetic portrait of a man who appeared to suffer from the prejudices and potentially unjustified hostility of the British establishment. Orth’s formidable research, supported by Vanity Fair’s exhaustive fact-checking, revealed a shocking picture of racial discrimination, sexual harassment and the bugging of staff at Harrods. The slogan ‘Enter a different world’ had acquired a very different meaning to that envisaged by Charles Harrod in 1834. Attractive female members of staff were required to take HIV tests in case Fayed was successful in having his wicked way with them, as he repeatedly tried to do. He sued for libel, but Graydon Carter, editor of Vanity Fair, stood firm. Along with Henry Porter, the London contributing editor, I collected evidence from the victims of such treatment.

The full extent of Fayed’s criminality became apparent to us when Bob Loftus, director of security at Harrods, courageously agreed to give evidence for Vanity Fair. When John Macnamara, Mohamed Fayed’s overall director of security and a former detective chief superintendent in the fraud squad, got wind of this, seemingly through covert bugging of Loftus’s phone, he got to work on Loftus in his characteristically ruthless manner. In 1991, Loftus, like so many Harrods employees, was dismissed facing a litany of false allegations concocted by Macnamara – in his case sexual harassment, perjury and drug offences.

The deal Loftus was offered was £90,000 compensation, with a 18draconian requirement that he did not cooperate with Vanity Fair in the defence of the libel action, plus a good reference for his next job as director of security at Harvey Nichols. Loftus resolutely refused to be muzzled. It was at some personal cost. What he received after substantial litigation was only £39,000 plus a reference making false allegations of dishonesty against him which caused Harvey Nichols to withdraw their earlier offer of employment.

‘If Loftus starts throwing pebbles at me, I will throw some dynamite at him,’ menaced Fayed. As it was, Loftus did cooperate with us and he helped unravel the extent of Fayed’s and Macnamara’s wrongdoing and track down additional witnesses to reinforce our defence of truth in Fayed’s libel action against Vanity Fair. Fayed was not slow in getting Macnamara to exact his revenge, as we shall see later.

Vanity Fair was the first to publicise the extent of Fayed’s sexual assaults and abusive treatment of young female employees. Hundreds of women in the United Kingdom are now in the process of bringing legal claims against Harrods after the broadcast of the BBC’s programme Al Fayed: Predator at Harrods in September 2024, following his death the previous year. Bearing in mind the time that has elapsed and the victims’ right to privacy, what we discovered about Fayed’s crimes is best summarised without naming the women. At the time of writing, there are potentially 421 victims of Fayed’s sexual abuse contemplating making claims against Harrods and possibly Fayed’s estate. The present owners of Harrods have stated that they are absolutely appalled at the allegations of abuse perpetrated during Fayed’s ownership before they acquired the store in 2010. They have stated that they are presently settling more than 250 claims for compensation brought by women alleging sexual abuse by Fayed.

One victim was as young as fifteen; Fayed was seventy-nine at the time he assaulted her. Most were in their early twenties. They 19were striking-looking, usually blonde and often searched out in the store to work in his private office by other Harrods employees.

They were to describe rape, attempted rape, being drugged, trafficked, Fayed entering their bedrooms without consent, demanding sex on occasions when they had travelled with him to Paris or gone to his flats in Park Lane as part of their work, being locked in their bedrooms by Fayed, being grabbed and groped, having their clothing ripped, being forcibly kissed and having £50 notes shoved down their blouses. If they refused Fayed’s demands, they tended to be sacked. One complained that she had been marched off the premises by a security guard holding her arm as if she had been arrested. Complaints often led to threats of making sure that they would never work again if they pursued their allegations. Added to this, they had to put up with their boss’s demeaning sexual language, such as whether they had had a good fuck at the weekend and if so, with how many men. Fayed would gratuitously insult and embarrass the young women at work. One was asked, ‘How is your pussy?’ Another was told that she was ‘wearing a fucking swimsuit’. Her shirt was ‘too tight on her tits’.

At Vanity Fair, Maureen Orth had also written about the shocking racism perpetrated by Fayed. While preparing for trial we secured further appalling evidence of the institutional racism that prevailed under Fayed’s regime at Harrods. A black lady being turned down for a job as a florist at Harrods had been described by a senior personnel officer as ‘unclean and unkempt with untamed hair and unpolished speech’ in what the chairman of the industrial tribunal called ‘an act of blatant racial discrimination’ as he rejected Harrods’ defence as ‘malicious and dishonest’. After our case had settled in 1997, the Carlton programme White Christmas demonstrated the contrasting fortunes of black and white job applicants. Orth noted that whereas Harrods had had thirty-two unfair dismissal claims the previous year, Selfridges had only two.

20This mirrored Fayed’s own views. When he saw a hard-working black cleaner, he stormed over to her, volubly complaining that she was ‘fucking too fat’, telling one of his assistants to get rid of her. He called Indians and those he referred to as ‘Pakis’ ‘smelly, black and horrible’. When Fayed discovered that a director of Asian origin was, like other directors, working on the fifth floor, near his own office, he called him ‘a fucking Paki. He is just a fucking piece of shit, find him somewhere downstairs.’

Not only was this language appalling and unacceptable, but it revealed a deeper problem at Harrods in the Fayed era. Although race relations laws had been in force for thirty years, in percentage terms Harrods was employing half the number of people from ethnic backgrounds in comparison to their competitors. What was particularly shocking was that managers at Harrods were willing to condone and turn a blind eye to this unlawful and outrageous racial discrimination.

Fayed had secretly and shamelessly recorded himself joking in a conversation with Tiny Rowland, ‘Give me one of those n***** cocks because I want a bigger one, I want a transplant.’

Gay people fared little better. Fayed called them ‘fucking p**fs’.

The extent to which Macnamara had established corrupt or improper links with the police emerged in our investigations. He was able to get dissident employees arrested on trumped-up allegations of theft. His links were particularly close with West End Central and Chelsea police stations. He told Loftus it was ‘amazing what they would do for a few readies’. There was one detective constable who typically received £100 for each assignment. Later Macnamara complained that the officer was ‘getting greedy’ and visiting the store for items like free suits too often. Macnamara would offer well-paid security jobs at Harrods and Fayed’s other companies to accommodating police officers when they retired at an early age with their police pensions. Hampers costing – in the 1990s – £120 21were liberally distributed to the lower ranks of police. Commanders at Scotland Yard received the £300 hamper. Sometimes they were auctioned for police charities but by no means always.

Such links had come in handy. In June 1993 Salah Fayed, Mohamed Al Fayed’s drug-using younger brother, inadvertently left his shoulder bag in a taxi when being driven from Aberdeen Airport to Mohamed’s Scottish estate, Balnagown. The taxi driver was a special constable and had unfortunately handed it in to the police. They found that the bag contained £4,000 in sterling, dollars and Swiss francs plus Salah’s passport. It also contained crack cocaine, a homemade pipe and white tablets. His young assistant, Rachel Crowe, a Harrods executive trainee, was persuaded to tell police the cocaine was hers and was charged. It soon became obvious to the police that she had no idea how to use the pipe.

Macnamara told Loftus he would take all action necessary. A few days later in the area just outside Fayed’s Harrods fifth floor office Macnamara introduced Loftus to Sir David McNee, a former Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police who had earlier in his career been Chief Constable of Strathclyde Police. McNee had recommended Macnamara to Fayed for the post of head of security at House of Fraser. McNee was supplementing his police pension by consultancy work for Fayed, screening employees for Balnagown Castle, it was said. Shortly afterwards, Macnamara told Loftus that McNee had intervened. McNee admitted he had been contacted about the case but unconvincingly claimed it was to seek his advice on Scottish legal procedure. Fayed had, however, instructed his solicitors D. J. Freeman in the matter, to whom Loftus was reporting, so he hardly needed McNee’s legal advice. A few weeks after meeting McNee, Loftus was telephoned by DC John McMillan, the officer in the case in Elgin, who told him he had been instructed by the Procurator Fiscal’s office that no further action would be taken against Crowe.

22Macnamara later told Loftus that Rachel Crowe had been seen with a black eye but that she had been paid to keep quiet.

Macnamara’s contacts with the police enabled Fayed to intimidate dissenting employees and to secure their silence. Sandra Lewis-Glass held a responsible position at Hyde Park Residence, a company that generated £4 million annually from renting out 170 luxury flats at 55 and 60 Park Lane, the profits being funnelled to another Fayed company in Liechtenstein. Fayed had made it clear to her that he did not want any of the black tenants to be housed in the 60 Park Lane building where he had an apartment – a particularly offensive instruction given that she was black.

When Westminster Council raised a levy of £1.1 million in respect of underpaid rates on the basis that these were short tenancies rather than long leases, Lewis-Glass was ordered to alter the letting documents to deceive the council into believing that they were in fact long leases, enabling a lower rate to be paid.

When she refused, Macnamara sent a surveillance team to record her anxiously discussing the problem with two of her colleagues in a Bayswater restaurant. She was sacked. Shortly thereafter no fewer than four officers from West End Central arrived at 8.30 p.m. at her Surrey home and arrested her for the alleged theft of two computer floppy discs worth 80p. She was locked in a cell at West End Central till 3 a.m., when she was released without charge. She later received a £13,500 payoff from Fayed.

Hermina da Silva, a nanny at Fayed’s home in Oxted, Surrey, was persistently propositioned for sex and molested by Fayed. When she complained to a Harrods manager, Macnamara told Loftus, resorting to police slang, ‘We’ve done a moody, she’s going to get nicked.’ She was dismissed in August 1994. She too was arrested and detained at West End Central, falsely accused of stealing property from Salah Fayed’s flat in Park Lane, where she 23had previously worked. She was, of course, not charged. She later received £12,000 of compensation from Fayed.

Fayed and Macnamara shamelessly used these tactics against all their opponents, however senior their position in the Fayed organisation. Christoph Bettermann had been deputy chairman of Harrods and chairman of Harrods Estates. He was also president of International Marine Services Inc., a maritime services company with a salvage and towage department, owned by Fayed in Dubai. When Bettermann resigned from Harrods in 1991, Fayed with Macnamara’s assistance sought to destroy him. Notwithstanding that Bettermann had converted a loss of $20 million into a profit of $15 million at IMS, Macnamara cooked up allegations that he had embezzled $900,000 during the salvage of an oil tanker, the York Marine, which had been damaged during the Gulf War and that he had over-calculated his annual bonus. Fayed sent a letter setting out these false accusations to the ruler and deputy ruler of Sharjah. IMS brought civil and criminal proceedings against Bettermann in Dubai. His passport was impounded and he had to lodge financial guarantees to secure bail. In the period February 1992 to December 1994 he was summoned to court on twenty-five occasions, where he was detained in a caged dock with the other prisoners. Eventually the charges were dismissed, but even then, IMS appealed, which was not dismissed until October 1994. Bettermann received £160,000 for wrongful dismissal and $160,000 in respect of his legal costs.

He sued Fayed for libel in England for the false accusations made to the rulers of Sharjah. Fayed’s solicitors, D. J. Freeman, aggressively defended the claims, seeking £329,993 as security for costs from the now relatively impoverished Bettermann in respect of his claims in England and to justify the allegations. This stratagem failed when it was appreciated that as Bettermann was a 24citizen and resident of Germany, security for costs could not be ordered and that the allegations could not be justified. As usually happened, Fayed’s defence was abandoned. Fayed had to pay £125,000 libel damages plus £287,500 costs. The case probably cost Fayed well over £1 million in all.