Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

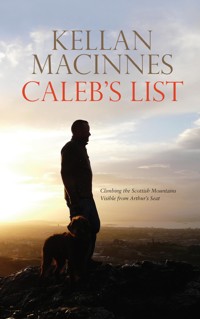

Shortlisted for the 2013 Saltire Society Scottish First Book award. Edinburgh. 1898. On the cusp of the modern age. Caleb George Cash: mountaineer, geographer, antiquarian and teacher stands at the rocky summit of Arthur's Seat. This is the story of Caleb, me and the Scottish mountains visible from Arthur's Seat. Somehow the Cashs or the Calebs didn't sound right so I have called the hills on Caleb's list The Arthurs. More than just a climbing book this is the story of a survivor. Caleb's List is a beautifully descriptive account in which Kellan MacInnes intertwines his own personal struggle with HIV with the life story of Victorian mountaineer Caleb George Cash, beginning with the moment in 1898 when Caleb stood at the top of Arthur's Seat in Edinburgh and made a list of 20 mountains visible from its summit, from Ben Lomond in the west to Lochnager in the east. MacInnes stumbled upon this long forgotten list of hills, now dubbed the Arthurs, and in this book he sets a new hillwalking challenge … climbing the Arthurs. Drawing on history, literature and personal experience, MacInnes offers both practical and emotional insight into climbing these hills, in an account that is a must-read for hillwalkers, visitors to Edinburgh and lovers of Scotland all over the world. This is not just a book about hillwalking and history. At its heart this is powerful landscape writing that explores the strong bond between a person and the hills they love . . . The author writes with skill and considerable authority. ALEX RODDIE, author Caleb Cash himself is an important if neglected figure in the history of the Scottish outdoors and the author's personal story gives the book an emotional power unusual in a guidebook. An excellent book. CHRIS TOWNSHEND, author A triumphant debut. THE GREAT OUTDOORS A tribute to the healing power of the Scottish landscape and to survival against the odds. THE SCOTSMAN

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 508

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

KELLAN MacINNES was born in 1963 and began hill walking when he was a teenager. For the past 24 years he has lived with HIV/AIDS. He holds an honours degree in psychology from the University of Aberdeen and currently works for one of Scotland’s leading charities supporting people living with HIV. He lives with his civil partner and their two dogs in Edinburgh in one of the streets at the foot of Arthur’s Seat. Caleb’s List is his first book.

Caleb’s List

Caleb’s List

Climbing the Scottish mountains visible from Arthur’s Seat

KELLAN MacINNES

LuathPress Limited

EDINBURGH

www.luath.co.uk

First published 2013

ISBN (print): 978-1-908373-53-3

eBook 2013

ISBN (eBook): 978-1-909912-06-9

Drawings by Kaye Weston

The moral right of Kellan MacInnes to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A percentage of net sales of this book will be donated to Waverley Care, Scotland’s leading charity supporting people living with HIV and Hepatitis C.

© Kellan MacInnes

Contents

Weathering the Storm

Acknowledgements

CHAPTER ONE Caleb’s List

The Heart of Darkness

CHAPTER TWO Kellan

CHAPTER THREE The Arthurs

CHAPTER FOUR Ben Lomond

Swimming with the Osprey

CHAPTER FIVE Ben Venue

CHAPTER SIX Mountaineer

CHAPTER SEVEN Ben Ledi

CHAPTER EIGHT Benvane

CHAPTER NINE CGC

CHAPTER TEN Dumyat

CHAPTER ELEVEN Stob Binnein

CHAPTER TWELVE Ben More

CHAPTER THIRTEEN The Battle for Rothiemurchus

CHAPTER FOURTEEN Ben Vorlich

CHAPTER FIFTEEN Ben Cleuch

CHAPTER SIXTEEN The Memory of Fire

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN Ben Lawers

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN Meall Garbh

CHAPTER NINETEEN Swimming with the Osprey

CHAPTER TWENTY Ben Chonzie

CHAPTER TWENTY ONE Schiehallion

CHAPTER TWENTY TWO Theatrum Orbis Terrarum

CHAPTER TWENTY THREE Meall Dearg

CHAPTER TWENTY FOUR Beinn Dearg

CHAPTER TWENTY FIVE Ben Vrackie

CHAPTER TWENTY SIX Beinn a’Ghlo

CHAPTER TWENTY SEVEN The Magic Stones

CHAPTER TWENTY EIGHT East Lomond

CHAPTER TWENTY NINE West Lomond

CHAPTER THIRTY The Age of Lists

Epilogue

CHAPTER THIRTY ONE Lochnagar

The City on the Hill

CHAPTER THIRTY TWO Arthur’s Seat

CHAPTER THIRTY THREE The Mountain in the City

APPENDIX I How to Use this Book

APPENDIX II Who Owns the Arthurs?

Bibliography and Further Reading

Checklist

Weathering the Storm...

SOMETIMES A MOUNTAINEERING BOOK is born out of human drama, suffering and struggle against the odds. In the chaos and bloodshed of World War Two while serving with the Highland Light Infantry in Egypt in 1942 the legendary Scottish climber WH Murray was captured by Rommel’s 15th Panzer Division. He spent the rest of the war in German Prisoner Of War camps where he wrote the classicMountaineering in Scotlandon sheets of toilet paper kept hidden from his prison guards. When Joe Simpson broke his leg at 19,000 feet on the north ridge of Siula Grande in the Peruvian Andes in 1985 with no hope of rescue he began to crawl down the mountain. The result wasTouching the Void. Sometimes a climbing book has its origins in more mundane circumstances.Hamish’s Mountain Walkwas conceived on a hot, stuffy day in the office and Muriel Gray wroteThe First Fiftyas an antidote to all those climbing books with pictures of men with beards on the cover.Caleb’s Listfalls somewhere between these two extremes, a book about mountaineering with its roots in the AIDS crisis of the late 1980s and early ’90s.

Acknowledgements

I WOULD LIKE TO THANK above all the following people for their help with this book; Kaye Sutherland for the drawings, Sue Collin for her critique of the draft manuscript, Alan Fyfe archivist at the Edinburgh Academy for the photographs and sketch of Caleb… and my partner Scott for understanding my long nights on the computer.

I’d also like to thank Chris Fleet for showing me Timothy Pont’s maps and June Ellner at the University of Aberdeen for giving me access to the copy of Blaeau’s Atlas once owned by Caleb. I am very grateful to the following people for various reasons; Marcia Pointon, Monica Jackson, Martin Moran, Alison Higham, Karin Froebel, the Royal Scottish Geographical Society, the Ladies Scottish Climbing Club, The Greek Consulate, John Paul Photography, Roy Dennis, Peter Stubbs, Colin Liddell, Bruce McCartney, Jonathan de Ferranti and Mercy Eden. Thanks to Tom Prentice for use of Munros Tables® which is a registered trademark of the Scottish Mountaineering Club.

Peter Drummond’s definitive workScottish Hill Names, Ian Mitchell’sScotland’s Mountains Before the Mountaineersand Andy Wightman’s pioneering website www.whoownsscotland.org.ukwere of great help while I was researchingCaleb’s List. Finally thanks to Gavin, Kirsten and Louise at Luath for the expertise, care and patience shown during the publishing of this book and for their commitment to a first time author.

CHAPTER ONE

Caleb’s List

The views from Arthur’s Seat are preferable to dozing inside on a fine day or using wine to stimulate wit.

ROBERT BURNS, 1786

EDINBURGH. 1898. On the cusp of the modern age. Caleb George Cash – mountaineer, geographer, antiquarian and teacher – stands at the rocky summit of Arthur’s Seat. Sounds drift up from the city below; the chime of church bells striking the hour; a horse and cart rattling down the cobbled streets past the tenements of Dumbiedykes. From the hillside nearby comes the bleating of sheep grazing on The Lang Rig. Caleb breathes in a yeasty smell of beer from the brewery beside the Palace of Holyroodhouse. A hundred years later a reconvened Scottish Parliament will meet where the brewery stands, but for now Edinburgh is quietly comfortable, part of Britain and its empire, sending its young men to fight in foreign wars like the one that will soon break out in South Africa.

The sound of a steam whistle. Clouds of white smoke pour from a blackened locomotive hauling a long line of coal wagons up the steep gradient of the Innocent railway to the sidings and engine shed in the Pleasance. At the base of Arthur’s Seat in wooded grounds stands a mansion, St Leonards, its four storey tower topped with pepper pot turrets. Nearby serried rows of glass roofs, Thomas Nelson’s Parkside printing works and on Queen’s drive figures in linen suits and straw boaters stroll by St Margaret’s Loch.

Caleb looks across to Calton Hill, its lower slopes encircled by the Georgian sweep of Regent Terrace. On its summit Caleb sees the telescope shaped Nelson Monument next to a half completed Greek temple.

Opposite the Royal High School stands the Calton Jail, and where the St James centre squats today are the slate roofs and chimney pots of Georgian tenements in St James Square.

The spires of the Scott monument rise above Princes Street but the clock tower of the North British Hotel, a landmark on the city skyline in the century to come, will not be completed until 1902. Cable hauled trams slide across North Bridge. When a cable jams, as frequently happens, it brings the entire tram network to a grinding halt until the fault can be repaired. The problems with the trams generate much heated discussion among the citizens of Edinburgh.

A crow on a nearby rock eyes Caleb sceptically. The crows were here when Iron Age farmers hewed the cultivation terraces on the slopes of Arthur’s Seat, and will hang on the breeze still after Caleb has gone to his long rest.

To the west at the edge of the Meadows, the domed roof of the recently built McEwan Hall. Nearby, George Square where the tower blocks of The University of Edinburgh stand today.

To the east Holyrood Park merges into the open countryside of East Lothian. At Lilyhill the new houses will soon stretch almost to the boundary wall of the Queen’s Park. Past the barracks at Piershill a ribbon of sandstone villas straggles along Willowbrae Road petering out around Northfield Farm, and Duddingston Mill a mile or so from the seaside resort of Portobello with its beach and pier. To the north beyond the tenements of Leith Walk and Easter Road and the chimneys and clock tower of Chancelot Mill lie the docks. White water foams against the Martello tower, and close by steam ships and sailing ships lie at anchor in the Forth waiting to enter the Port of Leith. Cranes and sheds dominate the shoreline near the new extension to the docks, but 60 years will pass before the tower blocks of Restalrig and Lochend are built.

Puffs of smoke rise from the funnels of steam trawlers moored beside the east breakwater at Granton harbour. Fettes College stands on the very periphery of the city among fields and trees. Beyond are islands: Inchkeith, Inchmickery and Inchcolm. Closest to Edinburgh is Cramond Island linked to the land by the Drum sands at low tide. Caleb can see the Fife fishing villages nestled into the north shore of the Firth of Forth. The Forth rail bridge completed nine years earlier spans the estuary where it narrows at South Queensferry.

Without the buildings of the 1960s and the big housing estates of the ’30s, Caleb’s Edinburgh is smaller and leafier. But it’s a smokier more industrial city too. Where the trees and grass of the Queen’s Park end, the chimneys of London Road iron foundry and the St Margaret’s locomotive works begin. Brewing, printing and banking are the main industries of this city. Among Edinburgh’s financial institutions are the National Bank of Scotland, the Commercial Bank of Scotland and the Royal Bank of Scotland.

Approaching the summit of Arthur’s Seat.

© Alastair White

As yet there are few motor cars, and children and dogs still wander freely on the streets. In winter late Victorian Edinburgh is a cold city of draughty windows, high ceilings and coal fires, each tenement belching smoke from two dozen or more chimney pots.

This is the city where a decade earlier Robert Louis Stevenson imagined Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde; its medieval old town crammed with slum tenements. Caleb lives and works in the city teaching the sons of the wealthy middle class at the Edinburgh Academy. The spire of the Tron Kirk and the dome of St George’s are prominent on the skyline of Caleb’s Edinburgh, and the general assembly of the Free Church of Scotland meets every summer at the Mound. Morningside ladies take tea at Jenners department store on Princes Street, but it’s only a ten minute tram or train ride to Great Junction Street in Leith where children play barefoot round the corner from the Sailors’ Mission at the Shore and the prostitutes.

To the south, a mile or so from Arthur’s Seat, Craigmillar Castle stands among fields of cows and copses of trees. The suburb of Morningside is spreading around Blackford Hill and the Braids as the city tide line creeps towards the Pentlands. South-east lie the Lammermuirs, the Moorfoots and the hills of Peebles-shire. But Caleb stands with his back to the hills of the Scottish Borders beyond which lie the Cheviots and England, his country of birth. It is to the north Caleb looks, beyond the shoreline where the city ends and across the Firth of Forth with its islands to the Lomond Hills of Fife, to the Ochils and Dumyat, to Ben Ledi, Ben Venue and Ben Lomond straddling the Highland boundary fault.

In places at the summit of Arthur’s Seat the rock beneath Caleb’s feet has been worn smooth by the passage of many feet, by generations of people over the years climbing the hill to see this view. Since he came to Edinburgh a dozen years earlier and climbed Arthur’s Seat for the first time Caleb has been fascinated by the view from the summit and by the topography of the city, the River Forth and the panorama of mountains to the north.

Alice sits beside Caleb, a notebook and pencil in her hands. Spread out around them are several Ordnance Survey one-inch to the mile maps weighted down with stones. Nearby is a brass theodolite on a simple wooden stand, carefully levelled and pointing north-west. Caleb puts his eye to the telescopic lens of the theodolite. After a moment he speaks; ‘Ben Lomond degrees west of north 73.’ Alice writes down the name of the hill and the bearing under the headingMountains Visible From Arthur’s Seat.Caleb adjusts the theodolite glances down at one of the maps speaks again; ‘Ben Venue degrees west of north 68…’

A few hours later the notebook Alice holds contains a list of 20 Scottish hills and mountains… Ben Lomond… Ben Venue… Ben Ledi… Benvane… Dumyat… Stob Binnein… Ben More… Ben Vorlich… Ben Cleuch… Ben Lawers… Meall Garbh… Ben Chonzie… Schiehallion… Meall Dearg… Beinn Dearg… Ben Vrackie… Beinn a’Ghlo… West Lomond… East Lomond and Lochnagar.

And so a new hill list was born.

In July 1899 Caleb published his list in the form of a simple table printed on page 21 ofThe Cairngorm Club Journal. Hugh Munro had published his list of Scottish mountains over 3,000 feet inThe Scottish Mountaineering Club Journaleight years earlier in 1891. During the 20th century Munro’s list became famous while Caleb and his list were all but forgotten. This is the story of Caleb, me and the Scottish mountains visible from Arthur’s Seat. Somehow the Cashs or the Calebs didn’t sound right so I have called the hills on Caleb’s listThe Arthurs.

The Heart of Darkness

The Congo flows through the provincial city of Leopoldville. The wide muddy river has been a trading route since biblical times. In the central market, among the baskets of yams and cassava, people and flies crowd around the bush meat stall… Sometime around 1912, while Caleb, thousands of miles away in Scotland sketched cup and ring marked stones in the Perthshire countryside a trader or perhaps a sailor left a ship in the port and went ashore into the hot African city night… a spherical particle of virus floating in his bloodstream spikes itself to a white blood cell, strands of dna mutate… a new sickness incubates faraway, very distant for now, for decades to come, moving undetectably slowly as the years pass but transmitting from one to another, to two, to three, to four… across central Africa… a shadow spreading out from the heart of darkness.

CHAPTER TWO

Kellan

And when he thus had spoken, he cried with a loud voice, Lazarus, come forth.

JOHN 11:43

IN THE YEARS AFTER World War One Edinburgh gradually expanded. During the early 1930s blocks of flats designed in the fashionable new art deco style were built in Comely Bank Road just along from the tenement where Caleb had lived 30 years before. Into one of the new flats moved Thomas, a printer by trade, and his young wife Margaret.

Tommy worked in a small printer’s workshop round the back of Broughton Street. On Saturday afternoons he would be sent to the Star Bar in Northumberland Place to carry back jugs of whisky for the men at the printers. Margaret worked as a buyer at the clothing chain Jaeger’s fashionable North Berwick branch. One weekend Tommy, showing off to Margaret in the outdoor swimming pool by the sea accidentally belly flops from the top diving board and winds himself. He has to be carried from the water.

After a miscarriage Margaret had one son Douglas. When he was 12, Douglas went to George Heriot’s, one of Edinburgh’s oldest private schools. Tommy and Margaret struggled and sacrificed to pay the school fees out of a printer’s wage.

Their flat in Comely Bank Road is furnished with the latest in art deco sideboards, armchairs, cut moquette sofas and glass light fittings. Margaret reads Proust while waiting for the potatoes to come to the boil in the tiny cluttered kitchenette. As women did then, Margaret had given up work when she married and suffered badly from post natal depression. Douglas would come in from school and find the hoover lying abandoned in the hall and know Margaret was not feeling well that day. ‘The evening paper rattle-snaked its way through the letter box and there was suddenly a six-o’clock feeling in the house’, wrote Muriel Spark of the Edinburgh of the 1930s.

His parents’ sacrifices had not been in vain and Douglas left Heriot’s to study English at The University of Edinburgh where he met Susan from Yorkshire. Susan’s father comes to visit her at university for the first time… it is the late 1950s and they walk along the path skirting the foot of Salisbury Crags and Arthur’s Seat. Douglas and Susan married in 1962 and their eldest child a boy, Kellan, was born at the Western General Hospital in December 1963, the year, according to Philip Larkin, sexual intercourse began.

Douglas and Susan buy a house in Craighouse Avenue with £1,000 given to the young couple by Susan’s grandfather, James Edward Collin. In the 1960s Kellan walks to school along the quiet back streets of Morningside.

Towards the end of primary school in the mid-’70s Kellan’s class are taken on the bus (dusty fabric seats) to the Lothian Outdoor Centre on Macdonald Road. In a former classroom Chris Bonington, the famous mountaineer, is delivering a lecture. Kellan remembers the bearded man sitting behind the school-type table, but what formed a lasting impression on a 12 year old mind were the brown blotches on the skin of his hands, the scars of frostbite sustained climbing the south-west face of Everest.

Douglas and Susan’s marriage folded under the pressures of the sexual revolution of the 1960s (or the ’70s by the time it reached Edinburgh) and Susan moves with the children to a flat in Marchmont. Kellan and his younger sister go to secondary school at James Gillespie’s High founded by a rich Edinburgh snuff merchant and rumoured to have been the school that inspired Muriel Spark to writeThe Prime of Miss Jean Brodie.To Kellan the school with its modern brick classroom blocks surrounding the medieval Bruntsfield House bore little resemblance to the school described in the pages of Muriel Spark’s novel.

The 1970s was the golden age of outdoor education in Scotland and Kellan was introduced to mountaineering by pioneering outdoor education teacher, Pete Main. He joined his innovative Tuesday Group, a mountaineering club for pupils at Edinburgh secondary schools, and spent two weeks climbing in the Austrian Alps. Back in Scotland with a school friend Kellan climbed the Five Sisters of Kintail, Ben Nevis and the Devil’s Ridge in the Mamores.

University in Aberdeen passes in a haze of sweet smelling hashish smoke and Friday night amphetamine. Summers are spent in Greece where it is too hot to walk further than the beach or climb anything higher than a bar stool. One morning awoken by the blinding Greek sun shining through a gap in the shutters Kellan climbs down a wooden ladder from the only inhabitable upstairs bedroom in the house. Bare rock forms the back wall on the ground floor of the 300-year-old villa. Kellan’s bare feet on cool stone as he climbs down through the trapdoor to the kitchen. Sees on the simple wooden table a plastic carrier bag with pots of Greek yoghurt, a jar of honey, Nescafé in a tin, bread. Someone’s bought an English newspaper too. Reads inThe Guardian’s mid-’80s fontRock Hudson Victim of aids Dies at 59.

Monica Jackson and Sherpas Mingma and Ang Temba on the first ascent of Gyalgan Peak, Nepal in 1955 and at home in Edinburgh in 2012 with the ‘eye-remover’.

Kellan left university with a degree in psychology and a boyfriend, and during the summer he graduated spends three weeks in Assynt in the far north-west of Scotland. One sunny day he climbs Suilven with Bridget, Morag, Graham and Aunty. Bridget was the ‘camp’ name of Kellan’s first boyfriend. Morag was David, and he and Graham had been a couple since meeting in a Gents public lavatory in Dundee in the early-’70s. Aunty, his boyfriend’s rotund, very camp ex-landlord climbs Suilven in knee length motorbike boots. And David and Graham’s collie Meg. There always has to be a dog… It’s a hot July day and on the way back Kellan and his boyfriend go skinny dipping in the sandy loch that lies at the foot of Suilven.

In the early-’90s Kellan was a once a month and summer holiday kind of hill walker. Being continually skint, equipment for winter mountaineering was a problem. Monica Jackson who led the first women’s climbing expedition to the Himalayas in 1955, lent Kellan her husband Bob’s ice axe. An old style two and a half foot long alpenstock it stuck out from the back of his rucksack and quickly acquired the nickname ‘the eye-remover’. In the days before Munro bagging really took off we climbed Schiehallion, the Tarmachan ridge, Bynack Mhor in the Cairngorms, Ben Chonzie, An Caisteal, Aonach Beag, Bidean nam Bian, Buchaille Etive Mor, the South Glen Shiel ridge, Liathach and Ben Vrackie.

The Heart of Darkness

One summer I noticed a spot on my left thigh. It stayed there for a couple of months, then after a Greek holiday and two weeks of sunshine the spot disappeared. But by the following January a similar kind of spot had appeared on my face. My left eye had begun to water uncontrollably at times and I felt more tired than a 33-year-old ever should. A young GP asked me if I had been squeezing the spot, I hadn’t. He arranged for me to see a dermatologist, but before the hospital appointment letter arrived, suspecting what might be wrong, Scott (my new partner) and I both went to the Edinburgh genito-urinary medicine clinic one bleak Monday morning in March.

I asked the doctor if he thought the spot on my face was Kaposi’s sarcoma, a rare form of AIDS related cancer. The doctor brought his face very close to mine as he examined the spot and said the best way to find out would be by taking blood and testing it for HIV. That was at 9.30am. After a traumatic six hours sitting on the sofa in our flat in Leith, we two boys together clinging, we were back at the hospital just after 3pm to be told I had AIDS… Scott’s blood test had tested HIV negative. I left the clinic dazed, clutching a prescription for valium.

CD4 count is a measure of the relative health of your immune system, usually somewhere between 800–1,200 in a healthy adult. Mine was 174. At an appointment with another doctor a week or two later my CD4 count had fallen to 66. The consultant thought I’d been HIV positive since the 1980s. I watched as the doctor hid the form he was filling in with his elbow. I didn’t read what he’d written. I didn’t need to. I knew the significance of the form. It was for patients who had less than six months to live.

If there can ever be a good time to get sick with HIV/AIDS I picked a good time. Combination therapy had been introduced a year earlier and I started on the drugs saquinavir, AZT and epivir plus a prophylactic anti-biotic to ward off pneumonia. Since 1997 I have taken between six and 25 tablets per day to stay alive. The drugs reduced the level of virus in my blood to undetectable levels and slowly my CD4 count began to rise.

At a dental appointment it was found Kaposi’s sarcoma had spread to the inside of my mouth. Within weeks I couldn’t breathe through my left nostril as the tumours spread. Six months of chemotherapy and radiotherapy were needed to treat the cancer. At the Western General Hospital a little man in a white coat and thick glasses takes a plaster cast of one side of my face and makes a lead mask for me to wear during radiotherapy. Every fortnight for three months I arrive at the oncology ward of the Western General Hospital, the most frightening place I have ever been. A nurse takes my blood to be tested and I wait for two or three hours to see if my immune system is strong enough to cope with a chemotherapy treatment. Then I would sit for an hour hooked up to a drip of liposomal donna rubicin.

I’m sure most of the other patients in the ward at the same time as me are long dead. As a boy I started to read Alexander Solzhenitsyn’sCancer Ward, never imagining (no one does) I would end up in an oncology ward one day. Side effects caused by HIV medication and cancer treatment included nausea, chronic diarrhoea and fatigue. I realised I was going to have to live the rest of my life with a chronic life threatening medical condition which fluctuates on a sometimes daily basis.

Some mornings I felt I could climb a mountain. Other days I could hardly get out of bed or go further than 10 feet from a toilet. Gradually though I began to recover. I was 33 years old. I didn’t plan on dying of AIDS.

A Dog Called Cuilean

Scott had always wanted a dog. Since he was a kid. I’d read research showing people recover faster from serious illness and tend to stay better if they have a pet, but uncertain about the idea I stalled; ‘maybe we’ll find a nice dog when we go on holiday to Assynt’. Hoping that might be the end of it.

Assynt… like Muriel Gray I’ve always fancied Assynt; ‘If Assynt was a boy I’d have knocked it to the ground with a rugby tackle and pulled its trousers down years ago.’

The first morning of the holiday, Scott drove the seven miles from Stoer to the nearest shop for supplies; rolls, bacon, Marlboro Lights. A brown envelope was sellotaped to the window of the newsagent’s in Lochinver, (life changing) words scribbled in black biro;

Free to a good home

Two border collie puppies

One black and one tan

Alan MacRae,Torbreck

‘Oh yes’, said the wifey in the shop, Mr MacRae was very keen to find homes for the pups… they were driving him mad… The next day Scott drove to Torbreck but couldn’t find Alan MacRae, only a herd of Highland cattle who surrounded the car thinking he’d come to feed them. Ann who we were staying with was less impressed; ‘you don’t want one of Alan MacRae’s dogs – they stand in the road and bark at cars’. I can’t say we weren’t warned.

Kellan at the summit of Sgorr Dhearg near Ballachulish in 1982.

Scott (second from left with Ben) had always wanted a dog. Since he was a kid…

Scott found the right house and Alan MacRae took him out to see the pups. A hole in the barn door was blocked with a plastic crate held in place by a tractor wheel. High pitched squealing could be heard coming from within, and as Alan MacRae rolled back the tractor wheel then pushed aside the plastic crate, a brown furry nose appeared.

We called her Cuilean (koo-lan), the Gaelic word for a pup, a cub, a whelp or asweetheart. I took the name from a Gaelic dictionary in Primrose Cottage at Stoer while the rain swept in from the sea.

The Stoer collies are a breed apart, nothing like Shep fromBlue Peter. The puppy grew up in to a long haired brown shaggy thing referred to variously as The Wookiee (Star Wars) or, ‘is your dog a mop/sheep?’

When the Vikings sailed in long ships past the Old Man of Stoer and the pillar mountain Suilven, to land on the white sands of Achmelvich (I like to think) a long haired brown dog with a wild look in its eyes, a distant ancestor of Cuilean, splashed ashore with them and raced off after a sheep.

That was 12 years ago. Cuilean the whelp mellowed into Cuilean the sweetheart. She doesn’t go on the high hills so often these days… asleep in the dog basket by the Rayburn as I write this.

We Have Won The Land.

Alan MacRae in 1993 celebrating the purchase of the North Lochinver estate for the people who lived there. The dog in the picture is Cuilean’s mother. The mountain is Suilven. © John Paul Photography

Leith

Three years before I was diagnosed with HIV I bought a flat in Leith on what was then one of the cheapest streets in Edinburgh. It was an elegant Victorian flat upstairs from a Scots Asian-owned food shop and off-licence. Every Friday night the kids from the nearby tower blocks congregated to swig bottles of cheap booze in a derelict side street across the road from the flat. Then around 9pm as eight per cent alcohol hit teenage brain cells there would be a loud bang as one of the plate glass windows of the shop downstairs was smashed.

Old sofas were set on fire in the street, the window above the entrance door to the tenement was smashed and lighter fluid poured onto the plastic door entry phone system and ignited. The benches in the park across the road from the flat were a popular venue for drinking large blue plastic bottles of cider. One day two policeman arrived at the front door to say a disabled man on crutches had gone berserk in the street and smashed up several cars including ours, front and back windscreen shattered.

In 2007 Leith police told Jabbar who owned the shop directly below my flat of a threat to firebomb it. I fitted smoke detectors in every room and made plans to move. With help from our families we sold the flat in Leith and relocated to one of the streets that skirts Arthur’s Seat. On the shelves of the local library in Piershill I foundA Guide to Holyrood Park and Arthur’s Seatpublished in 1987. Turning the pages I came across a list,Mountains Visible from Arthur’s Seat by CG Cash, frsgs. The list intrigued me. Who was CG Cash and why had he made a list of hills?

I took a compass and climbed to the top of Arthur’s Seat to identify the hills on the list. The day was cold, air clear, it was easy to make out the mountains – most were snow covered. Ben Lomond I could see to the west, next to it must be Ben Venue between two church spires… Ben Ledi – easy… Benvane over Dumyat yes, Stob Binnein and Ben More to the right of Fettes College, Ben Vorlich behind the Ochils, Schiehallion hmm? East Lomond, West Lomond, not sure about Lochnagar…

I sat there at the summit of Arthur’s Seat where Caleb stood a hundred years before. Watching the crows floating on the breeze with the city spread out below me. Sometimes I sit at the top of a hill and think. How lucky to be here… A long term survivor of HIV. All the lives still stolen by AIDS. From somewhere came the idea of climbing the Scottish mountains visible from Arthur’s Seat. Making a journey through a distant line of hills from 73 degrees to 1 degree west of north. I could survive HIV/AIDS… I could weather the storm… I could climb the mountains on Caleb’s List.

CHAPTER THREE

The Arthurs

The question has been many times asked, What Grampian and other summits can be seen from Arthur’s Seat?

CG CASH WRITING IN NOVEMBER 1898

EDINBURGH 2008. Standing on the orange carpet in Piershill library between the rows of large print and audio books… Arthur’s Seat is visible from the supermarket car park outside. While a librarian chases some kids from the Square across the road out the door, the first thing that strikes me about Caleb’s list is the similarity of its layout to Sir Hugh Munro’s famous tables of Scottish mountains over 3,000 feet. It strikes me that Caleb must have looked at Munro’s Tables inThe Scottish Mountaineering Club Journaland copied the layout for his list of Scottish mountains visible from Arthur’s Seat. During the 20th century Munro and his list would become famous while Caleb’s list was all but forgotten. It resurfaced, briefly rescued from obscurity in the 1980s, in Gordon Wright’s (long out of print)Guide to Holyrood Park and Arthur’s Seat, which is where I came across it one afternoon in Piershill library.

I’m curious. Who was CG Cash FRSGS? I wonder? What led him to compile a list of the Scottish mountains visible from Arthur’s Seat? The FRSGS bit is easy – in tiny print along the foot of the table I readReproduced by kind permission of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society. The list seems older than the 1980s guidebook it is reprinted in. I see a 1960s university lecturer with sports jacket and sighting compass taking bearings from the summit of Arthur’s Seat.

In fact the list is older and the truth more interesting. As well as being a geographer the remarkable CG Cash will turn out among other things to be one of the early Scottish mountaineers, a pioneer who explored the Cairngorms a decade before the Scottish Mountaineering Club held their first meet there. A man described by fellow climbers as having ‘a familiarity with, and a knowledge of the Cairngorm mountains almost unequalled’ and by historian Ian R Mitchell writing in 2001 as ‘a Scottish mountaineer of some note.’

Though I don’t know it as I stand on the orange carpet in Piershill Library, searching for Caleb will take me from the summit of Arthur’s Seat to the place known as the heart of the Cairngorm mountains. From concrete Strathclyde University to the forgotten volumes ofThe Cairngorm Club Journalin the National Library of Scotland. I will see an osprey for the first time and climb to the summit of Scotland’s highest mountain. I’ll sit under the ancient pines on the shore of Loch an Eilein and wander the narrow cobbled streets of Old Aberdeen. I’ll stand on the bridge over the Falls of Dochart and explore stone circles in the Perthshire countryside and cycle to a sandstone house near Cramond.

But all that lies in the future… for now back to Piershill library and Caleb’s list… rediscovered.

Caleb’s List of Arthurs as it appeared in The Cairngorm Club Journal in 1899.

Caleb’s list is printed as a table with seven columns. I run my eyes down the first column. It lists the names of 20 Scottish mountains visible from Arthur’s Seat, sometimes giving an old spelling of a hill name,Am Binneinfor Stob Binnein andSchichallionfor Schiehallion.

The second column gives the height of the mountain in feet as marked on the Ordnance Survey maps of the 1890s – Ben Lomond is 3,192 feet while on today’s maps it is 974 metres or 3,195 feet. The Scottish mountains visible from Arthur’s Seat range in height from Dumyat, the lowest at 418m/1,371ft to Ben Lawers the highest at 1,214m/3,983ft. All the Arthurs are over 300m/1,000ft in height.

Munro’s List of Scottish mountains over 3,000 feet. Caleb set out his list in a similar layout. [SMC]

Next the position of the mountain is given; Ben More and Stob Binnein are located in theBraes of Balquhidderand Ben Cleuch isHighest point of Ochils. Thus confusion is avoided between the two Ben Vorlichs in the southern Highlands and the Meall Dearg north of Strathbraan which is but one of Scotland’s numerous ‘red hills’.

Many of the hills on Caleb’s list lie along the Highland boundary fault which stretches from Loch Lomond in a north-easterly direction through Aberfoyle, Callander and Comrie then along Strathbraan to Dunkeld and Blairgowrie before reaching the east coast at Stonehaven. Formed when ancient continents collided the fault separates the sandstones of the central valley of Scotland from the older, harder rocks of the Highlands. The hills of the Scottish Highlands were once part of a much larger mountain range that stretched from Norway to the Appalachians. Many of the mountains on Caleb’s list are frontier hills… hills straddling an ancient geological boundary that remains a cultural dividing line today.

The fourth column gives the distance of the mountain visible from Arthur’s Seat in miles, again as measured on the Ordnance Survey maps available to Caleb in 1899. East Lomond is nearest at 20¼ miles away and Ben Dearg furthest 69 miles to the north.

Another column gives the general direction of the mountain from Arthur’s Seat – Ben Venue is WNW (west-north-west) and Ben Vrackie is NNW The most southerly Arthur is Dumyat, the furthest west Ben Lomond, the most eastern and northerly Lochnagar.

Column six gives the mountain’s position in the formDegrees West of North. Meall Garbh is 43½ degrees west of north and East Lomond 7 degrees west of north. The bearings are given in the form of degrees west of north because Caleb used a theodolite to compile his list. It is relatively difficult to pick out individual mountains from Arthur’s Seat using a compass because of the long distances involved. The way the light slants on the hills at different times of the day affects the view from Arthur’s Seat and a dusting of snow makes it easier to see the Arthurs.

The Lost Horizon

The final column of the table, headedGuide Line, gives the name of a landmark building on Edinburgh’s skyline, one of the islands in the Firth of Forth or a nearby hill which is in line with one of the 20 mountains visible from Arthur’s Seat. Unlike many British cities Edinburgh suffered little from the bombs of the Luftwaffe or the Brutalist architects of the 1960s, and the city’s horizon has changed comparatively little in the hundred years since Caleb stood at the summit of Arthur’s Seat compiling his list and noting landmark buildings on Edinburgh’s skyline.

Today Free Church College is better known as the meeting place of the general assembly of the Church of Scotland on the Mound and St George’s Church in Charlotte Square, easy to spot with its green dome, became West Register House in 1964. In the 21st century there are two, soon to be three, Forth bridges. Leith is more built up than a century ago and the east end of the ‘new’ dock extension on Caleb’s list can be identified today by a tall concrete grain elevator on the quayside of the Imperial Dock. Only two of Caleb’s 1899 ‘guide lines’ – Chancelot Flour Mill and the Leith Martello tower – are no longer visible from Arthur’s Seat.

Lists of Hills

As the recent ‘demotion’ of Sgurr nan Ceannaichean (913m/2,997ft) from Munro to Corbett status demonstrates, unlike mountains, hill lists are not set in stone. And like all hill lists, Caleb’s table of Scottish mountains visible from Arthur’s Seat contains it fair share of inaccuracies and inconsistencies. Most glaringly Caleb, a geography teacher who was always quick to draw attention to errors on Ordnance Survey maps, has himself erred in the guide lines column of his table confusing Bishop Hill and Benarty in Fife. Beinn Dearg, Ben Vrackie and Beinn a’Ghlo are in fact to be seen from Arthur’s Seat to the left of the steep scarp of Bishop Hill not Benarty.

The First Chancelot Mill

The Cooperative Wholesale Society’s Chancelot roller flour mill in Dalmeny Road, Bonnington. Caleb used the mill as a guideline for Meall Dearg. The building in the photo was demolished around 1970 when the present day Chancelot Mill opened at a site on the edge of Leith Docks.

© Allan Dodds

Caleb’s list of ‘mountains’ includes Dumyat and East and West Lomond, usually described as hills but included because they are such notable landmarks from Arthur’s Seat. They are the hills most often visible when the higher Arthurs are obscured by low cloud. Caleb had seen the Lomond Hills of Fife from the summit of Cairn Toul in the Cairngorms in August 1894.

Caleb’s list is of 20 mountains visible to the north of Arthur’s Seat in an arc stretching from Ben Lomond in the west to Lochnagar in the east. The Pentland Hills and the hills of the Scottish Borders to the south are omitted. On a sunny day looking at the view from the top of Arthur’s Seat it becomes clear that Caleb’s list does not includeallthe mountains visible to the north of Arthur’s Seat. Caleb it seems settled on a round figure of 20 hills from west to east. Ben Ime and Ben Vane in the Arrochar Alps can be seen from Arthur’s Seat, between Ben Lomond and Ben Venue, but do not appear on Caleb’s list and to the north-east in good visibility Driesh and Ben Tirran in Angus can be seen as well as Lochnagar.

Why Caleb omitted some of the mountains visible from Arthur’s Seat is an unknown. Another book could be written about the hills visible to the south of Arthur’s Seat. Caleb knew his list was incomplete; in a letter toThe Scotsmannewspaper he referred to his table as including;‘…mostof the ‘tops’ that can be seen from Arthur’s Seat.’ Caleb’s list of mountains is an arbitrary one, but omissions, inconsistencies and mistakes on hill lists seem to add interest and form part of their intrinsic fascination for some. As with old maps the errors on Victorian hill lists need to be seen in the context of their making, and are less important than what Caleb’s list of Scottish mountains visible from Arthur’s Seat symbolises; that to the early mountaineers the view of the distant hills was something new and exciting.

Leith Martello Tower. In 1899 the tower stood on offshore rocks, as seen in this RAFaerial photo taken during the Second World War. On Caleb’s List the tower is given as the guideline for East Lomond Hill. Today the Martello Tower is half buried on reclaimed land near the East Breakwater of Leith Docks.

[© Courtesy of RCAHMS (RAF WWII Air Photographs Collection). Licensor www.rcahms.gov.uk]

In May 1907 Caleb published ‘in response to numerous inquiries’ an ‘amended and extended’ version of his table which resolved many of the errors and inconsistencies of his original 1899 list.

Caleb climbed in the Scottish hills at the same time as the best known list compiler of them all, Sir Hugh Munro of Lindertis. Both Caleb and Munro died within months of each other at the end of the First World War, but Caleb remains a shadowy figure in the background of the world of Edwardian mountaineering, outshone by his more famous contemporaries, middle class men like Munro and AE Robertson.

Munro’s list of Scottish mountains over 3,000 feet contained many inconsistencies too. Over the past hundred years Munro’s Tables have been subject to several revisions. Most notoriously, in Munro’s original list the Inaccessible Pinnacle in the Cuillin Mountains on Skye was listed as a mere ‘Top’ despite being 26 feet (8 metres) higher than nearby Sgurr Dearg which was listed as a Munro.

Errors in early hill lists can be partly explained by the maps and navigational tools available to mountaineers at the time. Caleb’s list was compiled using a theodolite and Ordnance Survey maps a century before the creation of digital elevation models and computer drawn mountain panoramas.

Like other mountaineers of his generation Caleb encountered problems with the maps available to him in the 1890s. At the time Caleb compiled his list the Ordnance Survey produced two sets of maps for mountaineers; one-inch to the mile and six-inch to the mile maps. The problem was the two sets of maps contained separate, independent and different information! The one-inch maps (early versions of today’s familiar Landranger 2cm to 1km/1:50000 maps) had 250 foot contours, but few spot heights or names, while the six-inch maps (large scale maps roughly equivalent to 1:10000 today) contained numerous spot heights and names, but no contour lines. This must have made for traumatically complicated navigation, and certainly made life difficult for Hugh Munro when he was compiling his tables of Scottish mountains over 3,000 feet in height. About the absence of contours Caleb wrote inThe Scotsmannewspaper in September 1901; ‘Mountaineers are loud and frequent in their complaints…’

Geography Class-Room

EDINBURGH ACADEMY, 14 November 1898

GENTLEMAN. The question has been many times asked, What Grampian and other summits can be seen from Arthur’s Seat? I have made many pilgrimages to that pleasant spot, and have drawn up a table of all the summits I have been able to identify in the quadrant from West to North. It will perhaps prove of interest to some of your readers. I must admit that the identification of Lochnagar is not certain. I am, yours faithfully,

C.G. CASH

From Letters to the Editors,Edinburgh Academy Chronicle.

The Mountain Panorama

Panoramafrom Greek πᾶνν ‘all’ + ὅραμα ‘sight’

Wikipedia

What led Caleb to compile a table of the mountains visible from Arthur’s Seat? Partly it was his interest in the landscape of Scotland, but Caleb’s list also has its roots in the artist painted mountain panoramas of the Alps that became popular as tourism and mountaineering developed in Europe during the 19th century. Mountain panoramas handpainted in oil on canvas were quickly replaced by neatly folded paper panoramas which were included in guidebooks or sold to tourists. The mountain panorama never caught on to the same extent in Scotland as on the continent, but essentially Caleb’s list of mountains visible from Arthur’s Seat is a mountain panorama in tabular form.

Back home from the library a search on Google reveals Caleb was closely involved in the conservation of Timothy Pont’s 16th century maps of Scotland which include panorama-like drawings of Scottish mountains and these too may well have influenced him. The Cairngorm Club Journals of the 1900s contain several hand drawn mountain panoramas. Caleb’s fascination with the hills visible from Scottish mountains was a common characteristic of Victorian mountaineers. The view from the summit of a hill was still a new and novel phenomenon and a number of early Scottish climbers recorded the view from the mountains they ascended in great detail.

In Scotland, the most popular and successful mountain panorama was James Shearer’s 360-degree drawing of the view from the summit of Ben Nevis published in 1895 and reprinted in 1935 and 1980. Caleb describes using Shearer’s drawing to identify hills when he climbed Ben Nevis in August 1907 and this panorama may have inspired him to compile a list of the Scottish mountains visible from Arthur’s Seat.

Another form of the mountain panorama is the mountain indicator, a polished circular slab of stone or steel cemented to a cairn with the names of the distant peaks visible from that hill engraved on it. Mountain indicators stand on the summits of several Scottish hills including Arthur’s Seat, Ben Cleuch, Ben Vrackie and Lochnagar. Today the mountain panoramas of the 21st century are computer generated, based on digital contour data and available at the click of a mouse.

Later I will discover the Scottish mountains visible from Arthur’s Seat was not Caleb’s first list of hills, two years earlier in 1897 he had published a table of mountains in the Cairngorms over 2,000 feet. And while on holiday in the summer of 1898 Caleb was asked, ‘could the summit cairn of Braeriach be seen from Aviemore?’Caleb did not know, but he set to work to find out by drawing a panorama of the Cairngorm mountains visible from Aviemore railway station. It may be that a similar question back home in Edinburgh prompted him to compile a list of the Scottish mountains visible from Arthur’s Seat.

The First Arthurist?

Many people today enjoy ticking off hills from the lists of Munros, Corbetts and Grahams. In terms of their classification according to other (more famous) hill lists the Arthurs include eleven Munros, three Corbetts and three Grahams. There are only 20 Arthurs compared with 283 Munros, but they are a good ‘mix’ of hills; some classic southern Highland Munros, a couple of popular Corbetts and two of the best Grahams. The Arthurs have something to offer people of every age and level of hillwalking experience; from the family with young children climbing East Lomond, to the experienced hill walker making the long approach to Beinn Dearg in winter or climbing all the Arthurs in one expedition. Ticking off the mountains on Caleb’s list could form a good introduction to the Scottish hills or a coda to a lifetime of mountaineering.

Caleb’s list presents possibilities; from climbing Arthur’s Seat and – if the weather conditions are right – trying to see the Scottish mountains visible from its summit, to the challenge of climbing and ticking off the 20 hills on the list, the Arthurs. A list is a starting point. Finding Caleb’s list that afternoon will lead me to try and spot the mountains visible from Arthur’s Seat and then to climb all 20 of them (the first Arthurist? … hmmm) and, in time, to write these pages.

I leave the library, Caleb’s list in my pocket, cut through the supermarket car park heading for the blaze of yellow whin on the lower slopes of Arthur’s Seat.

MUNRO, CORBETTORGRAHAM?

An early president of the Scottish Mountaineering Club, Sir Hugh Munro was a landowner with a country house at Lindertis near Kirriemuir and an enthusiastic supporter of the Conservative and Unionist tendency in Scottish politics. Munro published his list of Scottish mountains over 3,000 feet in 1891 and there are currently 283 Munros.

John Rooke Corbett made a list of 219 Scottish hills between 2,500 feet (762 metres) and 3,000 feet (914.4 metres) with a drop of a least 500 feet (152.4 metres) between each listed hill and any adjacent higher one. Corbett was a Cambridge mathematician who became a district valuer in Bristol and joined the Scottish Mountaineering Club in 1923. His list was published posthumously in 1952.

A list of the Scottish hills between 2,000 and 2,500 feet in height with a re-ascent of at least 150 metres was compiled by Fiona Graham while she was convalescing from a skiing accident. The list of Grahams was published in 1992 and stands as a memorial to Fiona Graham who was murdered during a hillwalking holiday in Scotland in the 1990s.

CHAPTER FOUR

Ben Lomond

73 Degrees West of North

BEYOND THE TOWERS of Free Church College, 73 degrees west of north, Ben Lomond (974m/3,195ft) appeared a distant blue triangle on the skyline far to the west that day in 1898 when Caleb stood on the rocky summit of Arthur’s Seat compiling his list of Scottish mountains visible from Arthur’s Seat.

Anderson’s Guide to the Highlands and Islandspublished 50 years earlier in 1834 was one of the first guidebooks to Scotland. Written by two brothers based in Inverness it included information about the Scottish mountains and on page 340 I read;

Ben Lomond has perhaps been ascended by a greater number of tourists than any other of our highland mountains… the birds’-eye view of Loch Lomond itself, as seen from the shoulder of the hill, amply repays the labour of the ascent…

The mountain is a landmark on the edge of the Scottish Highlands visible from many places in Scotland’s central belt; from Glasgow, right across to Stirling and, on a clear day, from Arthur’s Seat in Edinburgh. Long ago an ancient language, Cumbric, was spoken in southern Scotland. The Cumbric wordllumonmeans a beacon, blaze or light. Like the Lomond Hills of Fife, the name Ben Lomond may be derived fromllumonand perhaps these hills were once used to send messages. The Scottish diaspora has led to hills across the planet being named Ben Lomond. There are Ben Lomonds in Canada, Australia and New Zealand. The Ben Lomond in the American state of Utah is thought to have inspired the opening credit of Paramount Pictures.

Scottish winter mountaineering could be said to have begun on the summit ridge of Ben Lomond in November 1812 when Colonel Peter Hawker and his companions were forced to cut steps in the frozen snow with their knives. In the early 19th century the idea of doing this for fun hadn’t occurred to anyone yet;

To get to the most elevated point of the shoulder we found impossible, as the last 50 yards was a solid sheet of ice, and indeed for the last half-mile we travelled in perfect misery and imminent danger. We were literally obliged to take knives and cut footsteps in the frozen snow, and of course obliged to crawl all the way on our hands, knees and toes, all of which were benumbed with cold.

Climbing Ben Lomond

Sron Aonaich meansthe nose of the ridgeand this is the easiest route up Ben Lomond sometimes referred to as the tourist path.Anderson’s Guide to the Highlands and Islands of Scotlandincludes directions for climbing Ben Lomond;

From opposite Tarbet the ascent (here rather steep) generally occupies two hours. At Rowardennan, opposite Inveruglas, five miles down the loch it is more tedious, but considerably more easy, and this is the route most commonly followed.

Begin from the car park at the end of the public road from Balmaha to Rowardennan just past the Rowardennan Hotel. Behind the visitor centre built in 2001 with creative use of local materials – oak frame, slate saddleback roof and mud walls, a path leads off into the woods through rowans and silver birches. In October when I climb Ben Lomond devil’s bit scabious is still flowering by the path and fungi sprout from the moss covered trunk of a fallen tree.

The footpath crosses a forest track and continues across ground where trees have been felled. Over the next 50 years the National Trust and the Forestry Commission plan to cut down the remaining conifers on Ben Lomond and replace them with native trees and shrubs. Clear felling looks ugly for a while but new trees and plants soon begin to cover the ground. The plan is to restore the mountain landscape recreating a natural transition from loch shore to mountain summit.

InOn Foot in the HighlandsErnest A Baker has words of reassurance for those feeling a little daunted by the prospect of climbing Ben Lomond. He quotes John Stuart Blackie, the famously eccentric Victorian academic who described the mountain as;

A Ben which possesses the double advantage of commanding a splendid prospect and presenting no difficulty of climbing, even to the most feeble and dainty-footed tourist.

The path climbs up through silver birches. All the time Ben Lomond and the Ptarmigan ridge draw the eye. In October the bracken has turned orangey-red and the heather faded from purple to brown. The hillside is turning to autumnal colours. The trees turning too. I pause and look down at Loch Lomond. Speedboats and jet skis create ripples and wave patterns on the surface of the loch as a sea plane flies past low over the water.

Chaffinches flutter around a solitary rowan, drawn to the tree’s red berries. On the west shore of the loch, Glen Douglas and the white painted Inn at Inverbeg. The path is well constructed breaking out into a flight of stone steps at one place. The tree lined Ardess Burn curves down to Loch Lomond where stone built Rowardennan youth hostel with its red painted gables stands in woodland by the shore.

Birches and rowan grow beside the Ardess Burn. Birch leaves lie on the grass and float in the water. A little further on the path reaches the grassy lower slopes of Ben Lomond’s south ridge, crossing the hillside through clumps of soft rush. Much work has been done on the Ben Lomond path by contractors and volunteers to repair erosion caused by the estimated 50,000 people who climb the mountain each year. At one time the old path was 25 metres wide in places. Today the path is paved with stones and impressive gullies draw rainwater away. Erosion by thousands of pairs of boots over the years has exposed the underlying rock. Bare rock now incorporated into the surface of the path.

If you climb Ben Lomond during the summer months and find you are not alone on the mountain, it was ever thus as Charles Ross’sTravellers’ Guide To Loch Lomondpublished in 1792 states;

In the months of July, August and September, the summit of Ben Lomond is frequently visited by strangers from every quarter of the island, as well as by foreigners.

Some kids camping near the path have left crisp packets and a disposable barbecue among the yellow deer grass and mossy lichen covered rocks. My mind clicks back to one January early morning driving west in Morag’s old Rover to climb Ben Lomond. Scott off work suffering from depression. The aftermath of my diagnosis with HIV… for him it was to be mountains as therapy. From Edinburgh through Stirling and the little villages on the road to Drymen, Scotland was asleep that Sunday morning.

WHO OWNS BEN LOMOND?