Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: 404 Ink

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

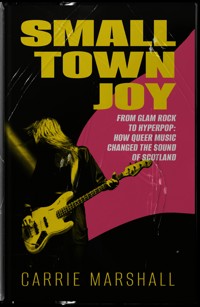

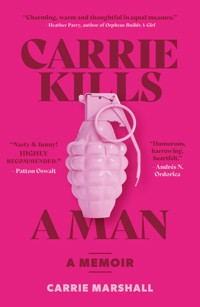

Carrie Kills A Man* is about growing up in a world that doesn't want you, and about how it feels to throw a hand grenade into a perfect life. It's the story of how a tattooed transgender rock singer killed a depressed suburban dad, and of the lessons you learn when you renounce all your privilege and power. When more people think they've seen a ghost than met a trans person, it's easy for bad actors to exploit that – and they do, as you can see from the headlines and online. But here's the reality, from someone who's living it. From coming out and navigating trans parenthood to the thrills of gender-bending pop stars, fashion disasters and looking like Velma Dinkley, this is a tale of ripping it up and starting again: Carrie's story in all its fearless, frank and funny glory. *"Spoiler: That man was me." – Carrie "Nasty & funny! HIGHLY RECOMMENDED." - Patton Oswalt

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 410

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

Praise for Carrie Kills A Man

“This was…quite a read. HIGHLY RECOMMENDED. Nasty & funny!”

– Patton Oswalt

“Carrie Kills a Man is a funny, insightful and highly relatable account of navigating the choppy waters of starting again when you thought you knew who you were. Carrie not only takes us through the intricacies of coming out as trans, but also invites us to see where our experiences align with hers, deftly puncturing the divisive rhetoric that often dominates this topic. Charming, warm and thoughtful in equal measure.”

– Heather Parry, author of Orpheus Builds A Girl

“Carrie Marshall invites us into her world and does not hold back. This memoir is humorous, harrowing, heartfelt and ultimately healing. Carrie powerfully reflects on both what one can lose by choosing to honour their truest self, but more importantly what she has gained. This book is an act of love and defiance against all the noise and bigotry clouding stories centred in power, love and truth. Long may such lives flourish!”

– Andrés N. Ordorica, author of At Least This I Know

Published by 404 Ink

www.404Ink.com

@404Ink

All rights reserved © Carrie Marshall, 2022.

The right of Carrie Marshall to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1988.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without first obtaining the written permission of the copyright owner, except for the use of brief quotations in reviews.

Please note: All references within endnotes were accessible and accurate as of May 2022 but may experience link rot from there on in. 404 Ink is not responsible for the content within linked third parties.

Editing: Kirstyn Smith

Proofreading: Heather McDaid

Cover design: Wolf Murphy-Merrydew

Typesetting: Laura Jones

Co-founders and publishers of 404 Ink:

Heather McDaid & Laura Jones

Print ISBN: 9781912489558

Ebook ISBN: 9781912489565

404 Ink acknowledges and is thankful for support from Creative Scotland in the publication of this title.

CARRIE KILLS A MAN

A MEMOIR

CARRIE MARSHALL

Contents

Content note

Introduction: Do you want to know a secret?

Part One: Smalltown Boy

Life is a minestrone

Goody two shoes

Sharp dressed man

Been caught stealing

We float

Girl afraid

Transgender dysphoria blues

We exist

Girls on film

Sexy and you know it

Crash

Love changes everything

Part Two: Black Holes and Revelations

Numb

Playing video games

Nowhere to run

Things will never be the same again

The act we act

I’ve got the power

We are family

Cherry Lips

Part Three: We Sink

Fa Fa Fa Fa Fashion

Shout, shout, let it all out

Part Four: Rip It Up and Start Again

Wrecking ball

Love and Pride

Sexy! No no no

Shame shame shame

Wildest dreams

What’s the story?

That’s not my name

Say my name

Flip your wig

Shake it off

Lose yourself

Merry Christmas everyone

Part Five: What It Feels Like For A Girl

Call me

It’s just history repeating

True Colours

Everybody hurts

High voltage

One day like this

The queerest of the queer

It’s different for girls

Suspicious minds

Part Six: New Rules

Music makes the people come together

Swim till you can’t see land

Yesterday, when I was mad

We live in a political world

Burn the witch

A nice day to start again

That joke isn’t funny any more

It’s the end of the world as we know it

Skin feeling

We walk with steel in our spines

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Endnotes

About the author

Content note

As comes with the territory of writing about being trans, please be aware that transphobia, homophobia, violence and suicidal ideation is discussed throughout Carrie Kills A Man, in many ways and levels of detail, across the entire book.

Introduction

Do you want to know a secret?

Some secrets are butterflies, gossamer-light with translucent wings. If they escape there’s barely a flutter; the most they’ll disturb is a few motes of dust. But some other secrets are barrels packed with plastic explosive, so unstable and so dangerous that you have to bury them deep and cover them in concrete. If you don’t, they’ll erupt with so much force that they’ll make the dinosaurs’ meeting with a meteorite look like a suburban dinner party.

I knew that my secret wasn’t a butterfly.

Some boys want to be Batman when they grow up.

I wanted to be Velma from Scooby-Doo.

Velma was super-smart, super-serious and sometimes sarcastic. I adored her. In her big glasses, oversized jumper and orange socks, she was irresistibly odd, bookishly beautiful and completely compelling. Daphne may have got all the boys’ attention, but Velma was the one who solved the mysteries.

I didn’t know that Velma was a lesbian icon back then. I didn’t really know what a lesbian was either. All I knew was that there was only one cartoon character I wanted to be, and it wasn’t Batman, He-Man or Captain Caveman.

I also knew that I needed to keep that very, very quiet.

In 2016, I had what appeared to be the perfect life. I was married to a beautiful woman. We had two beautiful children. We were living the suburban dream with all that suggests: the black Labrador, the Saab estate, the Jamie Oliver cookbooks in the kitchen and the Oyster Bay in the wine rack.

My secret threw a hand grenade into all of it.

Part One: Smalltown Boy

Life is a minestrone

Have you ever made minestrone? It’s really simple: some veg, some oil, some stock, a few cloves of garlic, some broken bits of pasta and some beans. As they simmer, the garlic and the veg and the tomatoes fill the air with flavours you can almost taste on your tongue: it’s a happy, homely aroma that brings to mind red and white checked tablecloths, bottles of Chianti in wicker baskets and a Gaggia coffee maker spitting steam in the corner. But no matter how many cookbooks I consult, no matter how many overlong online recipes I pore over, no matter how carefully I chop or cook or sauté or simmer, the minestrone I make doesn’t taste like the minestrone from the café round the corner or from the little Italian where everything is just like mama used to make.

That’s because minestrone is just a simple label for something incredibly complicated, a multi-layered mix of interactions between lots of different things. Even the most delicate deviation can have an enormous effect: a slight change in the ingredients, in the recipe or in the cooking method can completely transform what you end up with.

Conceiving a child is very much like making minestrone.

Not literally. Unless something is very wrong, sex should be considerably more fun and less likely to involve the use of cabbage or kale. But even the most complex recipe is nothing compared to the recipe for people, and as a result there are almost infinite variations in every aspect of our brains and bodies.

Even when people are genetically identical there can be profound differences. We come from the same genetic stock but my brother has dark hair, a strong build and normal feet; I have reddish hair, longer limbs and hammer toes.

Those things make me a beautiful and unique snowflake. Globally, 98% of people don’t have red hair. 97% don’t have hammer toes.

And, as far as we know, 99% of people aren’t transgender.

Transgender is when the gender you know you are, such as man or woman, doesn’t match the one you were assigned at birth when the doctor slapped your backside and proclaimed “it’s a boy!” or “it’s a girl!” Most people are cisgender, which means the doctor’s initial impression was correct. But doctors don’t always get it right. With my brother and I, they only had a 50% success rate. He’s cisgender, or cis for short. I’m not.

I don’t know why my recipe was subtly different to my brother’s. Maybe it’s genetic; maybe it’s hormonal; maybe it’s chromosomal; maybe it’s more than one of those things or something else entirely. Maybe something didn’t kick in when it was supposed to kick in, or maybe it didn’t kick as hard as it should, or maybe I was more kick-resistant than most.

Whatever the explanation, I ended up with a body that didn’t quite match who I am, a biological soup that wasn’t quite what I ordered. And because I’m British, I didn’t complain and I was too scared to send it back.

Hi. I’m Carrie.

Goody two shoes

I wasn’t born in the wrong body. I was born on the wrong planet.

Where other kids at my school obsessed over football, I was more interested in far-flung galaxies, space travel and sci-fi stories. I spent a lot of time daydreaming about them or staring in awe at the fantastic worlds and skyscraper-sized spaceships on the cover of sci-fi books. There was absolutely no doubt in my mind: I was going to be an astronaut.

Astronauts care little for earthly things, so instead of the on-trend Adidas satchels my classmates proudly wore I’d rock up to primary school with one of my dad’s old plastic briefcases full of model space rockets – a look that attracted the odd bit of negative attention and quite a lot of bemusement. I was regarded with some suspicion because I hated sport, talking about sport and being around people who talked about sport, and I couldn’t understand why I had to hang around with the boys instead of the girls, who seemed much more interested and interesting.

As if that wasn’t enough to make me stand out, I spoke with a different accent, I was new in town and I was younger than my classmates. That was because of my dad’s job: he worked for a construction company who moved us down the east coast of Scotland before cutting across to Ayrshire on the west. I’d started off in Inverness and moved down to West Lothian, where I was mocked for having an accent that was too posh; I changed it just in time to move to a different part of Scotland where my accent was now deemed too rough. One of the people who told me this was my next door neighbour, an older boy who wasn’t very nice to me but who grew up to be a very nice man. He’s my accountant now, but I have a long memory and I never pay his invoices on time.

I wasn’t bullied much, though. I’d have the odd parka-pulled-over-the-head encounter with some tiny fists trying to pummel my torso, but they were more like dancing than fighting. I didn’t experience anything particularly traumatic: I’d be called “poof” from time to time by people hoping to get a rise out of me, but even then I knew I was very bad at fighting so I didn’t rise to the bait. And I quickly found a protector in the form of Davy, a gruff, gentle giant of a boy who befriended me in much the same way you’d rescue a stray dog and who seemed to enjoy my company and my daft jokes. I didn’t quite cower behind his legs when I was threatened, but the other boys seemed to understand that if they messed with me, Davy would mess with them. Our friendship wasn’t based on that protection – it was more about debating which Madness song was best, swapping comic books and seeing who had the worst jokes; Davy was and is a funny guy – but I don’t doubt that if it weren’t for Davy I’d have had a much rougher time. If I were from another planet then Davy was the Elliott to my E.T., the friend who helped me navigate a world I didn’t understand.

I liked primary school. I came home with consistently glowing school reports, although my teachers despaired at my tendency to talk all the time. One of them, at her wits’ end after yet another barrage of questions, locked me in the stationery cupboard to stop me talking. My friends, I’m sure, have frequently felt like doing the same.

Primary school was also where I fell in love with books. I didn’t so much read books as inhale them, and according to my teachers, my reading age was double my actual one. Once I left primary school I began borrowing books not just with my own library card, but with my mum and dad’s cards too. I was drawn to horror – Stephen King’s Carrie, Christine and Salem’s Lot; James Herbert’s The Rats and The Fog; William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist – and SF, especially the bleak stuff such as Nevile Shute’s On The Beach and Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451. I also adored wry, funny SF by the likes of Kurt Vonnegut and Douglas Adams, both of whom had a huge influence on my sense of humour and on my writing style too. And I devoured endless crime novels ranging from the Scottish police procedurals of William McIvanney, and later, Ian Rankin, to the often repellent noir of James Ellroy and the macho mafiosi of Mario Puzo’s The Godfather. I’d take out ten books and finish them inside a week. To this day, I get really uneasy if I don’t have at least one unread book at home; I often accumulate vertiginous towers of to-read titles that I can topple in case of emergency.

Books were everything to me. An education – I often mispronounce words because I’ve never heard them spoken aloud; an adventure, taking me to the faraway galaxies I knew by now I wasn’t actually going to visit or showing me horrors that I hoped only existed in the authors’ imaginations; and more than anything, an escape. Books were a portal to other worlds, enabling me to escape not just from the outside world but from the cacophony inside my skull.

I can’t tell you exactly when I first tried on my mum’s heels or a skirt but it was definitely before I went to the big school, so it was several years before puberty. I remember a summer between primary school terms when I saw the family a few doors down playing in their front garden. The girls were a little older than me, and they’d persuaded, forced or bribed their little brother to dress in their clothes for their amusement. I recall seeing him and immediately going red from a mix of envy, embarrassment and confusion.

At home, I’d become fascinated by the women in the Littlewoods catalogue, the late-’70s equivalent of online shopping (and for older boys, the late ’70s equivalent of PornHub thanks to its pages of women in bras; the internet wouldn’t arrive for many more years). When nobody was around I’d stare at the girl-next-door models and the clothes they were modelling. I remember a very strong feeling of yearning, almost like when you have a huge crush on someone: there was a pull, a feeling that if I could just somehow enter the picture everything would be okay. I wanted to be as elegant and as beautiful as the women in the photographs. I wanted to be as beautiful as my mum, a tall, head-turning blonde who’d turned down the advances of footballer George Best at the height of his fame.

Had I been a cisgender girl, that wouldn’t have been a problem: we’ve all seen the trope of the young girl dressing up in her mum’s lipstick, pearls and heels a million times. It’s considered cute, because of course it is cute, and it can be a beautiful moment for mother and daughter. But it’s not considered cute or beautiful when boys want to do it.

I didn’t know much at that age, but I knew what the word sissy meant and that it was not something boys should be. But I couldn’t stop myself from wanting to see a very different me in the mirror, to feel more like the me I wanted to be. It felt right in a way I couldn’t articulate back then: the shiny polyester of an underskirt felt like a shiver against my legs, a sensation unlike anything I’d ever experienced from the clothes I’d worn as a boy, and as I layered up with a work skirt, American tan tights, M&S bra and pants and a plain but fitted blouse the different fabrics would move across each other in subtle, whispering ways. I’d try to keep my balance in too-big shoes, attempting to walk but only managing a stiff shuffle, but if I posed just right I could see my reflection in the mirrored wardrobe and see how the heels made my already long legs even longer. Dressed in everyday workwear I looked and felt like a business class Bambi: cute, unsteady and likely to fall on my arse any second.

Have you ever done the thing where you try something that’s above your pay grade – the really expensive facial scrub, the Egyptian cotton bedding with an incredibly high thread count, the birthday money bottle of wine or those huge fluffy bath sheets that you want to live inside and only ever come out of to scavenge for chocolate? That’s what female clothes felt like to me: satin sheets after sleeping beneath a scratchy, smelly old blanket.

It made me happy, if just for a short time. And it was always a short time, because I knew that if I got caught it would be the end of the world. I’d dress, totter around the room a bit while looking in the mirror and then carefully put everything back again. The happiness I felt faded fast and was replaced by much stronger, longer-lasting feelings I would become very used to: sadness, self-disgust and shame.

At night, I’d send secret prayers to God. I wanted him to kill me – painlessly in my sleep, because I’m a coward – and bring me back as a girl. He must have been on the other line because despite my best efforts for a very long time, he never did.

I hatched a plan. If God wasn’t willing to do it, I’d do it for him. So I decided I’d strangle myself. I’m very glad this was in the pre-internet era, because if it wasn’t I’d have googled the best way to kill myself properly – something I have done as an adult. But back then I was young, naive and completely unaware that you can’t strangle yourself with your own hands. I gave it a good go, but the best I could manage was to give myself a sore neck and have a bit of a cry.

I remember a school trip to see a pantomime - oh yes I do - and being utterly fascinated by the principal boy, a young woman playing a male character in tights and boots. But my only other memory of gender weirdness from that time is from when my family and I were in Belfast for our annual trip to see our extended family. During one of the many, many house calls we made – I come from a big family – I got to hang out with my favourite cousin, a smart, funny and pretty girl the same age as me. Photos were taken, and when they were finally developed months later I was struck by how similar she and I looked: it’s not an exaggeration to say that in that particular photo we looked like identical twins with our round freckled faces and bowl-cut bangs. I remember being fascinated by that photo and dearly wishing I actually was the girl I looked so much like.

I loved doing creative things at school, particularly telling stories, using language and trying to make music. Escapism was a big part of it – I spent most of my days daydreaming. Creative writing and plonking around on instruments I couldn’t play were really just opportunities for me to daydream out loud without being yelled at by a teacher – but I also loved being able to express myself without fear of being mocked by the boys. Like many people who don’t fit in, I was also quick to learn the power of being funny as a way of being seen without also being slapped.

I liked and I think I was liked by all my teachers bar one, my music teacher, who took an instant dislike to me and told me flatly that I didn’t have a musical bone in my body. A few decades later a different adult would tell me that I didn’t have a feminine one either. They were both wrong.

My main musical memory was of a day when we were allowed to bring records from home. I don’t remember the reason – it was probably an end of term thing, or maybe our teacher fancied himself as one of the cool teachers and saw an opportunity to ingratiate himself with us. Whatever the reason, I persuaded my dad to let me borrow one of his Reader’s Digest music compilations, a thick vinyl record in a vivid red sleeve. This was 1980, and one of the discs was a compilation of new wave and post-punk music. My choice of song, XTC’s ‘Making Plans For Nigel’, was played in class and made me cool in the eyes of the other boys for a whole day: they were all into bands like Madness, and the XTC song fitted really well with that. I remember the glow of approval, of feeling like I belonged, of being the person who brought along something cool that the others hadn’t discovered yet. My adult friends know that side of me very well: I’m always thrusting books and music links and longreads at the people I love because I want them to be as excited or as happy or as fascinated by those things as I am. Experiencing something is just the beginning for me: it’s the sharing of it, especially the sharing of joy, that makes me feel useful and alive and part of the world rather than just a passenger on it.

My love of music continued into secondary school and adulthood; I’m as in love with pop music now as I was back then. My timing was great. The early ’80s were a golden era for pop music and for magazines about pop music, which was going through an imperial phase of experimentation and innovation.

The ’80s were particularly good if you liked music by artists who messed with gender. I was fascinated by Adam Ant’s androgyny, Suzi Quatro’s leather, Boy George’s femininity, Annie Lennox’s masculinity and Phil Oakey’s lipstick and asymmetrical haircut. For a few years it seemed that bands couldn’t get on TV if the men didn’t wear makeup and don tea towels as headwear. I remember being fascinated by Culture Club’s debut album Kissing to Be Clever, which was in my house because my parents had bought it as a Christmas present for an older cousin. Before it was posted I’d stare intently at the cover, because while I knew Boy George was a man he certainly didn’t look like one in the cover photo. He looked fabulous.

There’s a trans joke I find bleakly funny: “At school I was bullied for being gay and being a girl. Turns out they were right.” I was, and they were. But I didn’t realise it at the time.

I started secondary school in the early ’80s when I was just ten. I remember it like it were a Ready Brek advert, the orange lining of our dark blue, dark green and black parkas like shards of light through endless shades of grey. In my memories the Ayrshire skies were always the same shade of grey Girvan sea, barely distinguishable from the roughcast council houses below them. I remember really noticing the West of Scotland architecture as Stranraer hove into view on our return ferries from family trips to Belfast, the red bricks of Northern Ireland replaced by roughcast grey, the streets’ cascades of cookie-cutter terraces replaced by symmetrical rows of semi-detacheds. On the bus to school in the mornings I’d wipe the condensation off the window using the sleeve of my parka so I could see the rain better, waiting for the giant monochrome and mustard blocks of Garnock Academy to loom out of the murk and announce the dawning of another dull day.

It couldn’t have rained all the time, I know. I remember heatwaves when the girls would come into school with the fronts of their legs painfully scarlet, the result of afternoons spent no-SPF sunbathing in lawn chairs when the words “skin cancer” weren’t widely spoken. And my memories of being outside school are all very sunny. But the West of Scotland is infamous for its inclement weather and the early ’80s were pretty gloomy too, so I’m sure that’s coloured my memories: instead of rose-tinted glasses, I see the past through Joy Division ones.

I was moving into secondary school while the valley around me was undergoing its own kind of transition. The car plant in Linwood where some of my friends’ dads worked shut down in 1981, the year before I went to secondary school, and the steelworks that employed so many local people and kept everything from the Co-op to the Chinese restaurant in business was in the managed decline that would see it close its doors and suck the life out of the valley in 1985. I remember the year before, when I was twelve, playing on a large patch of green land next to the bypass as Yuill and Dodds trucks with metal grates over their windscreens and heavily scuffed Scania logos thundered past at frightening speeds. They were en route to the Hunterston ore terminal in Largs, a regular convoy set up to try and destroy the miners’ strike by bringing in “scab” coal from South Africa and South America. I remember seeing the violent scenes of massed policemen cracking heads on the TV news, shocked that it was happening just ten miles from my house.

*

Starting secondary school at ten is unusually young. Most kids start at 11 or even 12, but I’d completed primary school a year early. That was a hangover from when my family moved about a lot during my earliest school years. When we landed in Ayrshire my parents were given the choice of sending me to a very small school with just a handful of pupils, or to have me skip a year and move into Primary Four in the town’s main primary school. They chose the latter, and because my birthday falls just before Christmas I was also in the younger half of the pupil intake when I went to the big school. As if that wasn’t enough, God or Strathclyde Regional Council decided to put me in a class with a disproportionate number of unusually big and strong boys, many of whom were two years older and considerably more physically developed than me.

The difference between 10 and 12 may not sound much, but it’s enormous. At 10 or 11 you’re still a child, and then your body hits the big red button marked puberty and suddenly your voice can’t decide which key it’s in and all your limbs hurt. And of course, bits of you get bigger and/or grow hairy. That was very much in the future for me, but for many of the other boys it seemed it was already in the past.

I hated and feared them. I particularly hated them during P.E., which was little more than regular humiliation by the older, stronger kids. It was a diet of football, rugby and other outdoor unpleasantness occasionally leavened with a bit of gymnastics or country dancing. The indoor stuff wasn’t exactly fun but it was the outdoors I quickly learned to hate. That was where I’d stand in the freezing rain waiting to be the last one picked; where I’d be shoulder-charged and pushed into puddles; where I’d fall on the red blaes pitch and end up pulling red ash chips from my tattered knees.

By the time I’d started secondary school I’d started to crossdress secretly and frequently at home. I desperately wished to be like the girls in my classes. I remember being in my first year, watching the girls playing hockey and netball and feeling 50% in love with all of the girls and 50% wishing I could wear the same skirts that they did – something I’d have been willing to endure actual sports for.

I got the sports but not the skirts. An awkward, skinny kid with glasses and biscuit-tin feet that couldn’t kick straight and who thought sports were a waste of valuable reading and listening to music time, I was a liability to any team. And after forty minutes of humiliation and horizontal rain, my reward for surviving was to shower with the other boys. It gave me – or perhaps just uncovered – a fear of communal showers and changing rooms that I’ve had all my life. It didn’t help that my body at the time was so different from the older kids’. To my ten-year-old eyes they weren’t boys, they were men. I was – and still am – terrified of men.

I was never attacked in the showers or anything like that. I didn’t fancy boys and at this point nobody assumed I did, so I wasn’t singled out for any of the homophobic abuse that some of the other boys would get. Or at least, I wasn’t for the first couple of years. I wasn’t mocked for my lack of muscles or body hair any more than any other awkward skinny kid, and I never suffered the indignity of the unwanted erection, something that got at least one of my peers a mild kicking. But there was something about the older kids’ aggressive nakedness that I found really intimidating, a shoulder-rolling, towel-snapping, dick-swinging swagger that I couldn’t imagine ever being able or wanting to do.

I felt like a lamb in a tiger cage. As an adult, I’d feel the same in gym changing rooms and swimming pool showers. Trans women are routinely demonised as predators, but I’ve only ever felt like prey.

Sharp dressed man

When I was eleven, I found something that I knew would change my life. It would earn me the admiration of my peers, the adoration of the girls and the respect of the boys.

It got me thrown into a bin.

What I wanted to wear to school was a white blouse, a grey cardigan and a grey lined knee-length skirt, like the girls I adored wore. But I wasn’t going to tell that to anybody for, ooh, decades. So what I asked my parents to let me wear was the same as the other boys: casual clothes and whichever trainers were fashionable that term.

What my parents actually let me wear was a black blazer, a white shirt that somehow managed to be too tight at the neck no matter how big a size we bought, black trousers with a razor crease and a tie that felt like a noose. So with the same desperation that would later motivate me to wear a “zany” tie to my office job, I begged my parents to let me at least choose a pair of shoes.

And what a pair of shoes I chose.

These shoes couldn’t have been more 1980s if forty years later they’d reformed and gone on tour to pay their tax bill. They were black patent leather brogues – oh yes! –with glossy red piping where the upper met the sole. Think Dr Martens without the height, the yellow threads replaced with lurid red. Were they comfortable? No, they were not. Were they practical? Not particularly. Were they the greatest shoes I had ever seen? They absolutely were.

They were perfect. They looked like Lamborghini sports cars, like Playboy-logoed bed sets, like KITT from Knight Rider. What could be more masculine?

My parents bought them for me on the Saturday and I proudly wore them to school on the Monday. I strolled into school like John Travolta in Saturday Night Fever, ready for the admiration and adoration that was surely coming.

After a full day of being called “poof”, of being shoved around and eventually thrown bodily into one of the bins, I put the shoes at the back of a cupboard and never wore them again.

I got the message. Don’t stand out.

I tried really hard not to, but for years I’d do my best to dress like everybody else and somehow still discover that I’d screwed it up. And on the very rare occasions when I managed to get it right, to wear the same thing as everybody else and not the Puma instead of the Adidas or the boots with the wrong number of lace holes or whatever other detail I’d managed to miss, God would sabotage me. For example, after the disco shoes disaster was forgotten I somehow managed to persuade my folks to get me a pair of Docs. Not only were they the right colour – black, of course – but they had the right number of lace holes too. They got a puncture three days in and I clump-hissed my way around the corridors for months afterwards.

It was around this time that I started writing songs to express my deepest truths. The chorus of one of them, “I Hate This Town”, was fairly typical.

I hate this town

I hate this town

I hate this town

I hate this town

My town and my school were in a former industrial powerhouse where the town centres were inhabited by more ghosts than shops. Like other industrial centres it had, and I think still has to some degree, a working class culture of strong, proud masculinity. Authors such as William McIlvanney (who grew up in Kilmarnock, just south of me) and Andrew O’Hagan (Kilwinning, a few miles to the west) capture it beautifully in novels such as McIlvanney’s The Big Man and O’Hagan’s Our Fathers:theseweretough towns where tough men did tough jobs.

When the jobs disappeared, the culture around them remained.

I think it’s fair to say that that culture did not exactly wave a rainbow flag.

From time to time I like to imagine what my life might have been like if I’d worked things out and come out as trans in my late teens or early twenties. Perhaps I’d have become a snake-hipped, androgynous rock superstar. More likely, I’d have had my pretty little head kicked in. The very few gay people I knew of back then faced extraordinary abuse, including physical attacks and bricks thrown through windows. In my town the word “poof” wasn’t just a taunt but a trailer: it was the shout that told you trouble was coming.

At the time, nobody really bothered to make a distinction between gay men – “poofs” – gender non-conforming people – “poofs” – and trans women – also “poofs”, because the newspapers didn’t. I remember reading my mum and dad’s Daily Mails and Sunday Times and my grandparents’ Suns with their tales of a “gay mafia” or “gay lobby” pushing a “vile” and “perverted” campaign to push a “homosexual agenda” and “recruit children”.

I remember seeing the Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, on the six o’clock news when I was 15. “Children… are being taught that they have an inalienable right to be gay,” she said, to rapturous applause. “All of those children are being cheated of a sound start in life. Yes, cheated.” Section 28 was introduced shortly afterwards, effectively banning any discussion of LGBT+ people’s lives in schools.

In 1987, The Sun – which ran stories with headlines such as “I’d shoot my son if he had AIDS, says vicar! He would pull trigger on rest of family too”1 – printed an editorial: “The Sun has never been hostile to the gay community… we reject entirely the claim by SOME gays yesterday that The Sun and the Daily Mail have run a hate campaign against them.” The same editorial urged its gay critics to leave the country on a one-way ticket and was headlined, “Fly away gays – and we will pay!”

This went on for many hateful years, and in Scotland it reached fever pitch in 2000 when the Keep The Clause campaign fought against the repeal of Section 28.

Keep The Clause was never a grassroots movement. The campaign was a collaboration between the millionaire Brian Souter, his PR consultant and the Daily Record newspaper with some help from Cardinal Winning, the Scottish Daily Mail and a handful of zealots. It was breathtakingly cynical, an attempt to reframe Section 28 not as blatant discrimination against LGBT+ people, but as a child safeguarding measure. It wasn’t so much a dog whistle as a foghorn: the queers are coming for your kids.

Sound familiar?

Many of the bylines will be familiar too. Several stars of the current trans panic were part of the gay panic too. Tabloids including the Mail on Sunday characterised AIDS as a “gay virus plague”2 while the Sunday Times, under editor Andrew Neil – who today chairs The Spectator – demonised gay men and printed despicable AIDS denialism while the disease was killing their loved ones.3 Over at The Sun, Piers Morgan, who now rails against “the howling woke mob”4 and gender fluidity and claims to identify as a penguin,5 wrote about a soap opera kiss between “yuppie poofs” under the screaming headline SCRAP EASTBENDERS6. Morgan also wrote a “Poofs Of Pop” feature in which he and a colleague gave “our totally ill-informed verdict on whether endless male pop stars were gay or not, and telephoning their agents for a confession or furious denial.”7

It’s hardly surprising that Social Attitudes Surveys of the time saw anti-gay sentiment, already high, rise during this period: the percentage of people who believed same-sex activity was “always or mostly wrong” was nearly 80% in both the US and the UK.8Because most people didn’t think they knew any gay or lesbian people – because who’d come out when the country thinks you’re the Devil? – the press, in cahoots with religious groups, reactionary right-wingers, police chiefs and malevolent millionaires, were able to incite fear and hatred of some of the most vulnerable people in society.

Many people they demonised are dead. But some of the perpetrators and their proprietors are still very much alive, and still using their power to incite hate.

The newspapers weren’t the only media demonising and mocking us. Films used queerness and crossdressing to evoke villainy in everything from Disney cartoons (well, hell-ooooo Scar! Hiya, Ursula!) to Dressed To Kill (one of Michael Caine’s worst films, which is saying something), Psycho, The Silence of The Lambs and TheRocky Horror Picture Show, while sitcoms were full of mincing gay men and what seemed to me like constant transvestism. I’m sure I have a bit of confirmation bias, but until relatively recently there really was a lot of crossdressing in English TV comedy: from portly comedians doing old-lady drag and Cambridge Footlights alumni playing deliberately unconvincing female characters to sitcoms sticking male characters in lingerie for laughs, it seemed that crossdressing was second only to racism in its innate hilarity.

I remember two characters in particular: Kenny Everett’s improbably breasted and bearded Cupid Stunt, a brassy, short-skirted socialite whose bawdy adventures were always done in “the best PAWWWSSIBLE taste”, and Herr Flick, a Nazi officer in the truly terrible sitcom ‘Allo ‘Allo. A running gag in the show was the sexual tension between the buttoned-up Flick and his subordinate, Helga, tension that would occasionally erupt; in one episode he and Helga both strip off to their underwear, with Flick behind a screen and Helga in the foreground. We then see Helga in a black and red corset, black stockings and suspenders before Flick provides the punchline: he emerges from behind his screen wearing identical underwear. This was something of a habit: in another episode, Flick is shown shackled in a dank dungeon while dressed in a different red corset and with a black bob wig. “Herr Flick, may I kiss you?” Helga says. “What? Kiss me, chained to the wall, dressed in the underwear of a woman?” Flick responds then pauses before continuing. “Of course.”

I didn’t find Cupid Stunt or Herr Flick hilarious, but they did make me feel funny.

Do you remember how it felt when you were watching TV with your folks and something slightly sexual happened on screen? The heat in your cheeks, the wanting to look but not wanting to be seen looking, the sudden awkwardness in the room? Take that memory and replace the tame on-screen action with the most lurid, outrageous, joyous depiction of whatever floats your sexual boat. Imagine the reaction as everybody in the room is shocked, horrified and scandalised.

Everyone except you.

You don’t feel shocked. You feel shame, because you feel seen. You too would very much like to be kissed by a woman who doesn’t care what clothes you’re wearing or who thinks they look hot on you. But that frisson of excitement, of recognition, is drowned out by the pounding of your heart. There’s ice in your stomach and fire in your cheeks because you know what you’re seeing, what you want, is not normal.

And neither are you.

Been caught stealing

I remember it in flashes.

The mess of the room. The plain black skirt hanging above yellow tights in the open wardrobe (yes, yellow tights. It was the ’80s). The Madonna poster on the wall, True Blue, an album I haven’t been able to listen to since. The first sound I heard: a gasp in the doorway, followed by the sound of the sister charging downstairs and, then, the sound of heavier footsteps coming up. The feeling of my heart trying to hammer its way out of my chest as, panicking, I ran for the safety of the bathroom. The shake of my hands as I slid the lock closed. The thumps and shouts of the mother demanding I open the fucking door right now. The look of utter hatred on my friend’s face.

What I’m going to describe now fills me with great shame. When I was twelve, I began sneakily crossdressing in the houses of my friends in clothes borrowed without permission from my friends’ sisters or mothers, improbably long toilet breaks enabling me to briefly swap my boy clothes for girl ones. I am deeply ashamed of and deeply sorry for doing it, and I don’t have any explanation or justification for it. As soon as the possibility of being able to crossdress entered my head it was like a loud car alarm going off. The only way to silence it was to try to look like a girl.

It wasn’t primarily a sexual thing, although at this point I was a teenage boy going through puberty so sometimes it was a turn-on in the same way that at that age the vibration of a bus engine, the sight of the back of somebody’s knee or just being awake was a turn-on. But mostly it was about imitation, not stimulation; emulation, not masturbation. I’d wear one of the incredibly frumpy grey pleated skirts the local school mandated and I’d try to see a different me in the mirror. I wanted to look like Jennifer, or Alison, or Gillian, or any other girl I was currently infatuated with and far too scared to talk to, let alone ask out.

I remember being torn between wanting to be with those girls and wanting to be like them; at the time I didn’t realise that those things didn’t necessarily have to be mutually exclusive.

In the language of the time, I was a transvestite. The term “trans” hadn’t been popularised yet; transgender was first used in the 1960s before I was born, but the shortened “trans” didn’t really become common until the mid-1990s. This is one reason it’s difficult to work out which historical figures were or were not trans: many people who’d call themselves trans today called themselves other terms instead. For example, Marsha P Johnson of Stonewall fame variously described herself as gay, a transvestite and a (drag) queen.1

On the basis of the very limited information available to me, I believed that there were just two kinds of T-people. The first kind were transsexuals, which occasional documentaries showed as figures of pity in ill-fitting floral dresses. I knew transsexuals wanted to have sex changes, which I didn’t, and to marry men, which I didn’t want to do either. Until very recently I believed that most trans people were heterosexual; that is, trans women were attracted to men. The reality is that most trans people are not heterosexual at all. In the 2018 UK National LGBT Survey,2 just 9.4% of trans people said they were straight; 71% were gay, lesbian, or pansexual and 5.4% asexual.

But I didn’t know that back then. Whatever transsexuals were, the girl-fancying me couldn’t have been one of them.

So that left transvestites. I discovered their existence in the lurid advertisements for a “He to SHE” dressing service in London that I saw in my grandparents’ copies of The Sun, in the problem pages of my mum’s magazines and in salacious tabloid tales of what Eddie Izzard would later call “weirdo transvestites” as opposed to the “executive transvestite” she considered herself to be. As Izzard tells it, executive transvestites travel the world, appreciate the finer things in life and are generally groovy; weirdo transvestites are maniacs like J Edgar Hoover whose crossdressing is revealed after their death and people go “well, that explains everything!” or cave-dwelling, heavily armed, goose-murdering madmen who are later discovered to have a huge collection of suspiciously sticky women’s shoes.

In the tabloids of the time, all transvestites were weirdo transvestites.

It was the same in the fiction I was devouring. Transvestites were considerably more common in the lurid crime and horror novels I enjoyed than they appeared to be in real life, and whenever they appeared in one of my library books they would either turn up dead or turn up to make everybody else dead. Transvestites were never the good guys, the kind, twinkly-eyed sheriff or the action man who saves the day. They were deranged, perverted killers or the sex workers those killers preyed upon.

I learned a new word from those books: tranny.

I hated that word. Still do. Some trans people have reclaimed it in much the same way some Black people have reclaimed the N-word, but for me the sound of it is the sound of somebody shouting it across the street or screaming down a telephone line late at night.

It was also the sound I heard in my own head. It’s what I began to see myself as, what I feared the other kids finding out about me, what I knew they’d call me.

The word echoed around my head.

Tranny tranny tranny tranny tranny tranny tranny tranny tranny tranny tranny tranny tranny tranny tranny tranny tranny tranny tranny tranny tranny tranny tranny tranny tranny tranny tranny tranny tranny tranny tranny tranny tranny tranny tranny tranny tranny.

I didn’t want to be a tranny.

Trannies were dirty. Deviants. Disgusting. Everyone knew that.

And yet that’s what I was.

I hated myself for it.

I hated the way the thought of crossdressing would pop into my head uninvited, the feeling of pressure building inside my skull until I couldn’t concentrate, the heart-thudding fear of being caught and the brief moment of calm when I looked in the mirror and saw something close to the me I wanted so desperately to be.

I’d try copying the mannerisms of the girls I liked, imagining I was one of them before carefully putting the clothes back in the cupboards I’d taken them from – or if I thought I’d spent too long already to risk taking any longer, into the washing basket. I’d then vow never, ever to do it again. And I wouldn’t, until the next time the thought came into my head and the pressure started to build.

Of course, crossdressing in other people’s houses is not just a very stupid thing to do, but a very risky thing to do too. It was just a matter of time before I got caught.

It happened when I was 13. I was at a friend’s house. We were watching Arnold Schwarzenegger’s Commando, one of many violent or horrific VHS tapes rented from a video shop that couldn’t care less about age ratings. It was pretty boring, and I excused myself to go to the toilet. The bathroom was upstairs, and the door to my friend’s sister’s room was adjacent. I hadn’t gone upstairs to crossdress, but as soon as I saw the open door the familiar noise in my head started up.

That noise was always the loudest sound I’d ever heard, drowning out everything else. It wasn’t a sexual thing, although it shared desire’s ability to make the whole world disappear when you’re in the moment. But desire is a want. This was a need