6,71 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

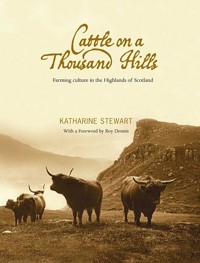

While their role has been all too often overlooked by historians, cattle played an integral part in the economy, ecology and culture of Highland life. Although many of these animals and their keepers have been abandoned in favour of sheep walks and deer forests, their legacy has remained through stories, paintings and songs. Infused by the author's own experiences of small holding at the end of the crofting era, this book offers an excellent insight into the social history and colourful customs assosiated with tending cattle on crofts, on shielings and on the drove roads of old, in an account that is populated by legendary figures, mighty beasts and characters larger than life. Perhaps most importantly of all, however, this is a history that looks to the future - a recent revival in cattle and traditional practices could pave the way for the truly sustainable agriculture practices so crucial to the fate of the planet at large.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

KATHARINE STEWART lives in Inverness. Born in 1914, she spent her early years in Musselburgh, and studied French at Edinburgh University. Then, during the war years, she worked for the Admiralty in London. She then moved to Abriachan, near Inverness, where she ran a croft and wrote documentaries for the BBC.

She has written numerous articles for various magazines, as well as several books. She was instrumental in setting up the museum at Abriachan. In April 2005 she received the Saltire Society Highland Branch Award for Contribution to the Understanding of Highland Culture, in recognition of her many works.

This book is for my family.

They were with me all the way.

First published 2010

eISBN: 978-1-913025-77-9

The paper used in this book is recyclable. It is made from low chlorine pulps produced in a low energy, low emissions manner from renewable forests.

Printed and bound by

Bell & Bain Ltd., Glasgow

Typeset in 11 point Sabon

by 3btype.com

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

© Katharine Stewart 2010

Contents

Acknowledgements

Foreword

Preface

CHAPTER ONE The Early Cattle

CHAPTER TWO The Caterans

CHAPTER THREE Summer at the Shielings

CHAPTER FOUR Droving

CHAPTER FIVE Hide, Hair, Horn and Hoof

CHAPTER SIX In the Kitchen

CHAPTER SEVEN Cattle in Story and Song

CHAPTER EIGHT Pen and Paintbrush in the Highlands

CHAPTER NINE Today

Bibliography

Chronology

Acknowledgements

I HAVE MANY PEOPLE to thank for help in the writing of this book – Janey Clarke of the Highland Livestock Heritage Society, Alistair Macleod, the Highland Council genealogist and Anne Fraser, assistant genealogist, the staffs of the Inverness Library reference and lending departments, and Una Cochrane, the writer on Highland cattle.

I would also like to thank my daughter Hilda, grandson Mark and son-in-law Jack Hesling. I should like to thank Leila Cruickshank and my editor Rob Fletcher for their help in putting the book together.

Special thanks go to Roy Dennis who wrote the foreword and contributed the photographs on pages 69, 78, 105 and 113.

Special thanks, also, to Jim Reid, grandson of Charles Reid, who kindly allowed his grandfather’s photograph of cattle in the hills to be featured on the cover of the book and for other phototgraphs on pages 101 and 102.

Foreword

KATHARINE STEWART’S NEW BOOK reminds us of our ancestry and heritage – a farming culture based on thousands of years of close partnership with cattle. She brings to the reader not only the pure pleasure of keeping cows, but also the friendships they create and the roles that the animals play in our history and culture. She also brings to mind remarkable images of the first Bronze Age travellers, who arrived in Britain with their hardy Celtic breeds, pushing aside the native aurochs as they sought grazing for their own domestic beasts. And thus started, as Katharine reveals, at least 5,000 years of a cattle society – a civilisation based around milk, butter, cheese, blood, meat, hide and bone.

Cattle are still in my blood, as they are in Katharine’s. I’m not very keen on sheep and goats and I’m rather shy of horses, but cows I enjoy. Although I’ve never regularly milked, I have felt the closeness of leaning against a flank and hearing the warm milk hit the bucket. I’ve also felt that pride of moving cattle from winter to summer grazings and back – the skittishness of cows heading for the hills with tiny calves, and the ‘holier than thou’ feeling of holding up tourist traffic on a narrow road. It is a way of reaching back to our roots and reordering the importance of the day.

My own life has been spent in nature conservation, a daily involvement with research and management of rare birds in the Highlands and Islands. In my earlier years, it occasionally involved travelling to a small loch above Loch Ness, close to Katharine’s old croft, where beautiful Slavonian grebes used to breed, and the book takes me back to those days.

It also reminds me of my lifelong desire to see ecosystems restored and functioning properly, and the wish to see the white-tailed eagle, red kite, beaver and lynx back where they belong. Sadly one mammal, the aurochs, cannot be restored, having been exterminated by Man. Thankfully, however, most of its genes and much of its behaviour have been saved in our domestic cattle. And traditional breeds farmed by traditional means can carry out most of the ecological roles in the countryside that their lost ancestors once performed.

The animals are essential for the ecology of our countryside and have a pivotal place in nature conservation. Yet, unfortunately, the numbers of cattle kept in this way have declined dramatically and continue to do so – courtesy of increased bureaucracy, keeping small numbers of cattle is now mind-blowingly difficult.

Yet there is a desperate need for more traditional breeds to be grazed on nature’s best lands, in order to help restore and manage these ecosystems for the benefit of all fauna and flora. At the same time it should be made easier and more profitable to keep them, and we should try to restore cattle to their rightful place in society – as Katharine illustrates in this beautiful book.

Roy DennisMBE

Preface

Cattle on the Croft

SOME FIFTY YEARS AGO my husband and I came from Edinburgh to work a croft in Caiplich, Abriachan, a small settlement 800 feet up in the hills to the north of Loch Ness.

My husband’s forebears were crofters in Perthshire and I had farming ancestors in Galloway, so agriculture must have been in the blood. Before we moved north we had grown food in a small way, had kept poultry and bees and had escaped to the hills whenever we could.

In Caiplich we found ourselves in a community of crofters, native to the area, who all spoke Gaelic as well as English, and worked their crofts in the traditional way. They made us, and our small daughter, unreservedly welcome.

We soon acquired a small herd of black Aberdeen Angus cattle, then three score blackface sheep, numerous poultry and Charlie – a garron or working pony, who soon became one of the family! We also had a tractor, one of the few in the immediate vicinity.

After a while we became competent enough to take part in the usual community activities of clipping and dipping the sheep, of harvesting, of herding cattle and so on.

Our daughter, Hilda, like all croft children, also joined in happily – feeding motherless lambs from a bottle and dumping sheaves of corn into stooks. Later she would gaze in amazement as the travelling threshing-mill arrived and began to turn the sheaves into grain and straw.

We followed the usual five-year rotation of crops – oats, grass for hay, potatoes, turnips, then fallow. The oats were harvested with the binder and made into stacks, which was a communal job. Making hay was another community activity, although we sometimes had to hang it on the fences to dry before stacking! The potatoes and turnips were stored in clamps – long shallow pits covered with straw or rushes to keep out the frost.

On winter evenings we enjoyed many a ceilidh, a gathering in someone’s house, for the exchange of news and gossip and perhaps a tune on the ‘box’, as the accordion was known, and a song or two. Our neighbours would tell us about people and happenings of older times, their powers of recall amazing us.

They told us of one neighbour known as ‘The Drover’, droving being in his blood. The days of the long droves to the south were over, of course, but he still liked to take cattle on the hoof, even the ten miles to the market in Inverness. He would collect twenty or thirty beasts from the area, two or three boys would have a couple of days off school to deal with the herding, and off they would go. A stop overnight in a friendly farmer’s field and they would be fit and fresh for the market early next morning.

One day, it seems, they were too fresh. In spite of frantic herding by the boys, when passing down the High Street of Inverness a frisky bullock crashed into, of all places, a dairy! Not too much damage was done, compensation was arranged for later, and the drove moved on. That story made the headlines in the local press.

Part of our small herd grazing the rough ground

When we asked why a small island in the burn which ran through our croft was called the ‘island of cheeses’ we were told that cheese made up in a shieling on the hill to the west had by mischance landed in the water and been carried downstream before being washed up on the island. It was still edible, despite its perilous journey!

These tales and others, told with all the verve and accuracy of the born story-teller, brought the past vividly before us.