Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: 404 Ink

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

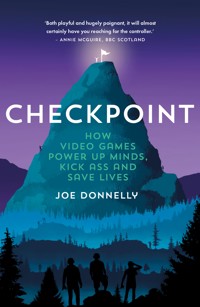

You're probably familiar with tired cliches around gaming culture in the media... that video games are violent and damaging. That they're for children, or society's outcasts; for the lazy and those without purpose. Joe Donnelly is here to tell you that video games, in fact, save lives. They saved his. Inspired by his own experience navigating depression following a tragic personal loss, Checkpoint reflects on the comforting and healing effect that entering into new digital worlds and narratives can have on mental health both personally and on a wider scale. From the big-budget triple A studios, to the one-person indie set-ups, there are thousands of eye-opening games exploring human complexities overtly and subtly all waiting to enthrall and comfort players old and new. Through exclusive, in-depth interviews with video game developers, health professionals, charities and gamers alike, Joe makes the case for the vital value of gaming culture and why we should be more open minded and willing to pick up a controller if not for fun, for the well-being of ourselves and our loved ones. Shortlisted for the Saltire Society's Non-Fiction Book of the Year.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 335

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Checkpoint

Checkpoint

How video games

power up minds,

kick ass and

save lives

Joe Donnelly

Contents

Checkpoint

Content Warnings

A Note on Spoilers

Foreword

Introduction

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Glossary

Endnotes

List of featured games

Acknowledgements

About Joe Donnelly

If you need someone to talk to Samaritans are a mental health charity and service for crisis and support.

Whatever you’re going through, you can contact Samaritans in any way below:

Phone: call from any phone on 116 123.

It’s free, one-to-one and open 24 hours a day.

Email: [email protected]

and they will respond to you as soon as they can.

Write:

Chris,

Freepost RSRB-KKBY-CYJK,

PO Box 9090,

Stirling,

FK8 2SA.

They aim to reply within 7 days.

More information: samaritans.org

Content Warnings

AnxietyChapters 1, A New Challenger Appears (Johnny Chiodini), 5, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12

Bipolar disorderChapter 2

Borderline personality disorderA New Challenger Appears (Luna Aitken)

DepressionChapters 1, A New Challenger Appears (Johnny Chiodini), 2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 12

Miscarriage & fertilityA New Challenger Appears (Lauren Aitken)

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD)Chapters 1, 7

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)Chapters 2, 9

Self-harmChapter 7

Sexual assault, trauma & rapeChapters 1, 2, 5

Substance use & addictionChapter 4, 6, 10

SuicideIntroduction, A New Challenger Appears (Johnny Chiodini), chapters 3, 4, 5, 7, 10, 11, 12, 13

A Note on Spoilers

Discussing video games and media means sometimes discussing all elements of them, including endings and pivotal narrative moments. Checkpoint will occasionally engage with video game endings, which may include spoilers for some readers. I have tried to the best of my ability to provide markers where there may be spoilers and where you can continue reading without anything being revealed.

Look out for this message in-text:

(Spoilers! Skip to the next message to avoid.)

There will be another message in the following paragraphs or pages which indicates where you can safely continue reading.

If you wish to experience any of the games in this book for yourself, go to the list of featured games at the end of the book where you can find all games mentioned in one comprehensive list, including the platform, whether PC, console or mobile.

Foreword

When I first prepared the pitch for a book that celebrated the benefits of video games on mental health in early 2019, I knew exactly what I wanted from the project, what I wanted it to say and how I was going to write it. I had written about video games and mental health on several occasions previously, in various publications, as both areas are close to my heart, for reasons you will soon discover. At one point during my career as a video games journalist, I had a monthly column for VICE which explored both subjects and their complex intersections, which was great, but I wanted to be able to add a bit more of me and my own personal experience. I wanted to tell my story, to map out my journey, its highs and lows, to help others and encourage them to share their voyage with this concept. I wanted to dig into how video games have and continue to support me through dark times, while helping me better understand mental illness – concerning myself, and in a wider contextual sense – and in doing so, I wanted the book to explore some of the independent and mainstream games on the market which either represent or are inspired by, a range of complex mental illnesses.

I was delighted when the publishing company 404 Ink were interested in my pitch and wanted to publish in May 2020. I could not wait to get started. Then I quickly realised what might be obvious to most – there’s a big difference between writing a 1,500-word feature article about a single game for a website and writing a book of near 300 pages about my life and the lives and work of gamers; developers, publishers, writers, health professionals and more. No pressure. While I’d always loosely used my first-hand experiences with depression and anxiety to frame my journalism, the need to dig into very personal and difficult past experiences to guide a whole book’s structure was much harder than I expected. In all ways. As difficult as it’s been to revisit moments and memories from the last few years, getting those words down on paper have been worth it, and I hope you will think so too by the last page.

I submitted my final draft of Checkpoint to 404 Ink on Thursday, March 5th, 2020. I received a lovely typeset proof by Monday, March 9th. And, with only a handful of checks, nips and tucks left to go, the book was on-schedule to go to print in April to be released into the world in early May. Two weeks after receiving my typeset proof, the United Kingdom, following numerous other countries around the world, went into lockdown as a result of the novel coronavirus pandemic, COVID-19.

Overnight, everyone in my corner of the world in Glasgow, Scotland was forced indoors, to distance themselves from friends and family and avoid a disease predicted to potentially kill millions if not controlled. The hardships some people have endured through not being able to see loved ones and carers for an extended period of time has been unimaginable. Lockdown has been an essential preventative measure but it will have, and is already having huge impacts on health, both physical and mental, as unemployment soars, a recession worse than the Great Depression looms, and, most heart-wrenchingly, children, parents and grandparents die in busy hospitals, alone, mourned via long-distance video call funerals, attended in-person by a strictly restricted gathering only in the single numbers. By this stage, around 10 weeks into lockdown, most people I know have some kind of connection with someone who has been sick, or who has lost a loved one during the most controlled stretch of quarantine, unable to spend their final moments together.

The mental quandaries during this time cannot be underestimated. The people fortunate enough to keep regular working hours have been forced into irregular working-from-home regimes. Those furloughed under the UK Government’s Job Retention Scheme have been, in essence, pushed into mandatory employment breaks with nowhere to go. And those who have been made redundant are jobless during a time when most employers are not hiring. My girlfriend Jenny and I were lucky enough to land in the first category, but with a toddler to entertain, and a surprise pregnancy thrown into the mix, our work/life balance has hardly been straightforward.

When the world went into lockdown, with international flights and holidays being cancelled for the foreseeable future, the role of video games at home came into sharp focus for a route to escapism. Suddenly, sun hats and flip flops had to be replaced with consoles and controllers. Virtual worlds offered entertainment in ways reality couldn’t, something underscored by the fact that games such as Call of Duty, FIFA, Overwatch, Candy Crush and World of Warcraft reported player-number spikes of several million during the first few months of global stay-at-home orders.1 With schools temporarily closed in some countries, kids escaped into the digital playgrounds of Fortnite and Minecraft; and parents, who may have otherwise ignored the medium entirely during normal circumstances picked up a control pad and took the time to understand the online worlds within which their children so often explore and socialise.

I finished writing Checkpoint before COVID-19 took grip, but in the light of the coronavirus crisis, the position of recommending video games to help cope with, balance or improve mental health became all the more relevant. Isolation is often a central tenet of mental illness, not least the depression and anxiety disorder I live with myself, and thus at a time when self-isolation was enforced, the importance of tools which can help alleviate these conditions became vital in that process.

Whether it be Zoom call quizzes with family and friends, reliving your childhood in games like Sonic Mania, reinventing yourself on your private island in Animal Crossing: New Horizons, or becoming one of the nearly 900,000 players who became virtual coaches during Football Manager’s two-week free trial period in March. Over 600,000 people who’d never played FM contributed to the 21 million matches played and 40 million goals scored2 – a new precedent was set for gaming in many households in Scotland, the UK and beyond. With mental health in mind, Football Manager also changed all of its in-game advertising to promote mental health charities during its free trial, which was a nice a touch, and was also forced to sidestep a third complimentary week at the advice of British emergency services who had noticed a sizeable dip in internet bandwidth in certain areas of the country.

In these uncertain times, there are of course more important things than book delays. While the publication of Checkpoint has been pushed back by a few months, its main message still stands and only gets stronger with time. Maintaining sound mental health is the most important thing to me, and I strongly believe, now more than even when I handed in the manuscript, that video games can educate, inform and hold our hands as a tangible coping mechanism. Let me be clear: I am not a mental health professional, nor a video game developer, which is why I’ve spoken to those better qualified in these areas throughout Checkpoint to complement my personal experiences. I hope you enjoy it and continue to stay safe, physically and mentally; wherever you are in the world, however the 2020 pandemic touched you.

Joe Donnelly

June, 2020

Introduction

A Player Has Left the Game

From the front door, I could hear my mother laughing. Then I realised she was crying. Not only was she crying, but she was also bawling – inconsolably roaring from her bedroom upstairs – as my father greeted me at the door. I stepped into the hallway and he forcefully ushered me into the living room, my mind struggling to comprehend what was going on. Nobody likes to see their parents upset, but there was something particularly unsettling about hearing my mum so audibly grief-stricken from another room. I didn’t see her face, her stare, or her tears, and yet I created an image in my head and I will never forget it.

Later, I learned that my mum avoided my return home that day to gather some composure while my dad relayed the news to me, but instead of the calm she hoped for, her momentary absence had caused her to break down. She’d received the news that morning, you see, and had to wrestle with it all day. I, on the other hand had been at work, and then up at Strathclyde University to sit an entrance exam for an English Literature degree course I’d later get accepted onto but would never actually start.

My dad sat me down in the living room, the evening sun beaming through its bay windows. He quietly said, ‘Your uncle hanged himself today.’

* * *

On May 12, 2008, my uncle Jim killed himself. No matter how many times I write that sentence down it still shocks me. That moment from twelve years ago, at the time of writing, set me off on my mental health journey, one which has delivered a handful of highs, a fair number of lows, and an inadvertent, but enlightening, degree of self-discovery.

I’ve learned a lot from books, film and television in my quest to understand the depression and anxiety I now struggle with; brought on, so say doctors, by the brutal nature of my uncle’s death. I’m also an avid video game player, and while becoming a fully-qualified plumber and gas-fitter upon leaving school in my late teens, I’ve since retrained as a fully-qualified journalist who once specialised in writing about video games. I did so because the interactive and persuasive nature of video games allows the medium to engage and inform on a level that the traditional media I listed above, simply cannot.

Reading, watching television and listening to the radio are all examples, I believe, of two-dimensional activities. The person on the telly – the newsreader, the actor, the documentary maker – tells you something; you listen, you watch, you consider the information and, most likely, move on with your day and forget all about it. Video games, on the other hand, require you to engage on a multi-dimensional level. Imagine turning your game console on, watching your chosen game load up, and then placing your control pad on the floor. That game isn’t going anywhere without your input, and for that frozen screen move, or to progress through the game’s story, to understand whatever it wants to tell you, you’ve got to make it happen. The game tells you something, you listen, you watch, you consider the information, and then you make it move on. All of which puts video games in a unique position to explore interpersonal themes – such as my focus on issues of mental health, including suicide, depression, and a wealth of other sensitive and complex subject matters – by virtue of player agency.

Before we continue, let me first ask you a question: are you a gamer? You might be, you might not be, and you might not realise you are. If you play video games, you’re a gamer. Simple as that. Maybe your Friday night consists of a few beers and a game of NBA 2K20 on the PlayStation 4 with some basketball-loving pals; or perhaps you play Fortnite: Battle Royale on your PC with random folk online. Perhaps you play Super Mario Odyssey on a Nintendo Switch handheld while sprawled out on the couch after a hard day at work, or maybe you’ve scouted every noteworthy rising star in Football Manager 2020 on your dad’s work laptop. (Don’t worry, I won’t tell. I’m not a grass.) Maybe your game of choice is animated cooking simulator Overcooked, which you play with your significant other on Xbox One. I mean, I say “play”, but if you’re like anyone I know, I bet your sessions end with you screaming at one another in real life, as your on-screen avatars set fire to the room around them thanks to a neglected pot of overboiled tomato soup. Seriously, if your relationship can survive half an hour with that game then you’re in a good place.

Maybe you don’t play games on a console, a handheld, a PC or a laptop, but you play Candy Crush on your smartphone or you are a Farmville veteran. Maybe the effortlessly addictive Angry Birds is more your cup of tea, or you’re hooked on playing Coin Master, Texas HoldEm Poker or 8 Ball Pool on Facebook – the latter of which welcomes 10 million players every month to the game via the social media platform.1

If any of this applies to you, then you’re a gamer. The internet likes to apply distinctions regarding how serious you take gaming, but luckily most of them are pedantic and don’t matter. The most common is the perceived difference between “casual” and “hardcore” players, where people who play games on their phone tend to fall under the former grouping and those who commit more of themselves to the activity land in the latter. Elitism isn’t uncommon among those who identify as hardcore gamers, but in 2020, I find the distinction to be false and tired. It’s also worth pointing out that just about everyone with a mobile phone – be that a smartphone or anything less sophisticated (I adored Snake 2 on my Nokia 3310 back in the day) – is a gamer.

One distinction which I would say is relevant, however, is the one between professional and non-professional gamers. Esports – also known as electronic sports, e-sports, or esports – is a form of sporting competition tied to video games. Esports take the form of organised, online multiplayer video game competitions and tournaments, contested between professional players, individually or as teams. It’s a billion-dollar industry,2 a huge part of modern gaming, with events watched by millions around the world with competitors play for multi-million-dollar prize pools. Naturally, the most successful esports players take video games very seriously. Those people are, to be fair, pretty hardcore.

Besides the pro versus non-pro distinction, though, I don’t care much for separating casual and so-called hardcore gamers. Video games should be fun, informative, and inclusive, no matter how often you pick up a control pad, sit in front of a mouse and keyboard, or tap the screen of your phone. And even if you don’t feel you fit any one of those profiles, nor consider yourself a gamer by any stretch of the imagination, I bet you know someone who does. I also bet you’ve crossed paths with video games, inadvertently or otherwise, while consuming other media. In the last decade, video games have improved at exploring the real-world themes covered in the usual media – politics, love, lust, relationships, friendships, depression, suicide, you name it – yet when traditional media aims at video games it can be hit or (a big) miss. For every charming and endearing Wreck-It Ralf, there are video game tie-in movies like Hitman: Agent 47, Assassin’s Creed and Warcraft waiting to spoil the party.

Perhaps the most interesting depiction of video games in television in recent years is Charlie Brooker’s science fiction anthology series Black Mirror. Before his TV writing and presenting days, Brooker wrote for the now-defunct video games magazine PC Zone in the mid-’90s so he understands the landscape and nuances of video games more than most. To date, the show has aired four episodes that are explicitly about video games – Season 3’s “Playtest”, Season 4’s “USS Callister”, Season 5’s “Striking Vipers”, and a one-off special named ‘Bandersnatch’. The latter is a choose-your-own-adventure-style endeavour about a young programmer named Stefan Butler (played by Fionn Whitehead), who dreams of adapting a choose-your-own-adventure book called Bandersnatch into a revolutionary adventure video game.

In doing so, ‘Bandersnatch’ turns the TV show itself into a fully-fledged video game. By inputting binary decisions via their television’s remote control, users (players?) can shape the show’s outcome via a network of branching narratives. This format of storytelling is synonymous with video games, but, having played it for the first time as it launched in late 2018, it was the first time I’d seen a gaming-like function executed with such finesse on ‘traditional’ TV. I won’t spoil the specifics of the plot because you should try it for yourself (‘Bandersnatch’ is available on Netflix), but ultimately the user’s choices begin pretty lightweight – the first decision to made involves breakfast: Frosties, or Sugar Puffs? – and gradually begin to weigh heavier with each plot twist and fork in the narrative road.

In pursuit of five different endings in ‘Bandersnatch’, it’s possible to make mistakes in your choice selections, which can ultimately drive the story to a dead-end – just like the books that it draws inspiration from. Anyone who grew up in the ‘90s, like me, will remember the Goosebumps horror series’ take on choose-your-own-adventure, and will likely also remember how frustrating it was to wind up dead through the process of bad decision-making. The frustration is no different here. Still, ‘Bandersnatch’ can be dark, funny, and unsettling – at once and at the click of a button – much like many of the video games it strives to reflect.

In conversation with PC Gamer’s Andy Kelly shortly after ‘Bandersnatch’ was released, Brooker himself said a common criticism of the episode was that video games have been using player-driven branching narratives for some time, and they now do so in more sophisticated and complex ways, to which Brooker’s reply was: ‘Yeah, they are, but they’re not running on Netflix. This is not a gaming platform!’3

Which is, of course, what stands ‘Bandersnatch’ apart, placing it in this curious limbo between television and video games, tentatively bridging the gap between passive and interactive entertainment. Despite praise from some facets of the media that said ‘Bandersnatch’ was a new form of storytelling, Brooker disagreed – ‘It’s basically [Rick Dyer and Don Bluth’s 1983 video game] Dragon’s Lair, but a different iteration of that’ – but he did admit that if people play his creation and like the idea of interactive storytelling, it may lead them to try something more advanced. Something more advanced would be video games, wouldn’t it? If you were taken by ‘Bandersnatch’’s gamified methods of engagement, there’s a whole universe of video games out there that take the concept and stretch it further than you could imagine. Whether you’re a hardcore gamer, a newly enlightened casual gamer or a straight-up non-gamer (I’ll convert you yet), you’ll have been affected by video games in some way.

* * *

One of the most interesting and satisfying things about my experiences writing about video games and mental health for the Guardian, New Statesman, Telegraph and VICE, among others, is the fact that doing so has prompted a number of my close friends to share their struggles with mental health too – and these are stories which might have otherwise gone untold. Hailing from working-class backgrounds in Glasgow, a city privy to an obstructively self-deprecating, self-effacing, keep yer chin up, pal culture, I think that’s quite remarkable.

Speaking to the BBC in 2018, Andy Przybylski, the Director of Research at the Oxford Internet Institute, who studies how video games impact our mental health, said: ‘Nobody is properly talking to each other’, in reference to games and mental health.4 Checkpoint aims to pick that control pad up from off the floor and kickstart that discussion through the lens of the biggest and most successful entertainment medium in the world.

To be clear: anyone struggling with their mental health should seek the help of qualified professionals should they be able, but no matter what your own circumstances are, I hope this book speaks to you, or someone you know if you pass it on, or at least helps broaden your understanding of video games and the medium’s power to stir emotion and convey information in and around an often stigmatised subject matter. As I tell you about Uncle Jim and the games I played in the aftermath of his suicide, you’ll hopefully see a subtle road map of my mental health journey and maybe you’ll see yourself on a similar path, or not at all. Whatever you see in this book, I hope you’ll take something positive from it.

Chapter 1

A New Journey

Setting the Scene

I’ll get straight to the point: if no one is talking to each other, then we simply need to start talking to each other. This is especially the case in Scotland, my home, and mental health issues are killing at record levels. Two people take their own lives in Scotland every single day.1

Some more terrifying statistics set the scene within just the UK (worldwide analysis on suicide rates is widely available from the World Health Organisation):

Over 5,600 Scottish males have taken their own lives since my uncle’s passing in 2008.2

680 suicides were registered in Scotland (522 males and 158 females) in the same year.3

Scotland had the highest suicide rate in the UK in 2018, with 16.1 deaths per 100,000 people (784 deaths), a year where males accounted for 17.2 deaths per 100,000 people up and down the country – a trend that’s been consistent for 10 years.4

The statistic you’re probably the most familiar with: Suicide is the single biggest killer of men under 45 in the UK, and 84 men take their own lives every week.5

Despite the Scottish national average suicide rate falling more recently, the rate of suicides amongst young men in Scotland increased for the third consecutive year in 2017.6

Aye, but it’s a coward’s way out, says the whisky-nosed man in the pub, who preaches outdated machismo rhetoric about safeguarding stiff upper lip stoicism, and how it’s only women and pansies who should cry and share their feelings and, heaven forbid, rely on emotional support should they ever need it. Needless to say, that’s antiquated bullshit. And the man from the pub is an arsehole.

Oh, but they didn’t seem like the type of person that’d kill themselves, says the casual well-wisher, whose would-be wholesome exchanges, bless them, invariably spiral into a blur of blank stares, hollow sentiments and awkward shoe-shuffling. Don’t get me wrong, I wish there was a universal profile, a stereotype, a cookie-cutter personality for suicide – if there was, we’d be better equipped to identify and, crucially, help those in need – but there’s quite simply not.

Overcoming modern misconceptions, then, is surely as important as hurdling age-old stigma when it comes to gaining wider mental health discourse. On finding out your uncle has killed himself… how exactly do you process that? The answer is that you don’t. At least, not right away.

Instead, you spend the best part of a year grieving, you piss off to Australia for two years to distance yourself from it all, you return and get listlessly consumed by a tidal wave of unresolved emotion and resentment, spend another year trying to come to terms with what the fuck is going on inside your head, consult a doctor and then postpone seeking treatment for another 36 months or so. And only then, six years down the line, do you finally engage with the help on offer. If any of this journey is relatable, I hope you did a better job of managing it than I did.

In my defence, I didn’t really know what depression was before my uncle’s death. Then 22 years old, I certainly didn’t know how to identify it, and I wasn’t equipped to articulate how it might, in turn, affect me. After my previously-mentioned journey, I’ve since taken advice from GPs, I’ve undergone cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT), and have been on a course of anti-depressant medication for nearly six years. During those times, video games played an equally important role in my coming to terms with it all.

At the time of Jim’s suicide, I hadn’t long started playing Irrational Games’ BioShock. Inspired by the dystopian hellscapes of George Orwell, Aldous Huxley and Ayn Rand, the first-person shooter game drops players into Rapture, an underwater civilisation, built by fictitious idealist dictator Andrew Ryan, designed for the perceived higher echelons of society to live and work free of ‘petty morality and government control’. After discovering a DNA-altering, superpower-granting property named ADAM, the world gets hooked, humanity crumbles, and Rapture’s addicted citizens evolve into gibbering, drug-addled, zombie-like monsters named Splicers. I felt tenuous links between this game and my harsh reality, the shooter video game doubling as a coping mechanism. Maybe I made a subconscious link between my uncle’s death and fighting a race of unbalanced blighters who once sought a better life, but who instead wound up trapped by circumstance. In the years leading up to his passing, Jim embarked on a pretty significant career change into property development which, after accruing debt unbeknownst to my family and his friends at the beginning of the global financial crisis, was pivotal in his death. Or maybe I was just looking for a distraction.

Either way, I threw myself into BioShock like no other game I had played before. I killed Splicers for fun, and I found bashing their heads in with the game’s hulking melee wrench weapon extremely satisfying.

* * *

Ever since their commercial introduction in the 1970s, video games have told stories. Naturally, technological improvements and innovations over the years have allowed for more sophisticated storytelling – 1972’s Pong, for example, weaves a less complex narrative than, say, 2018’s Red Dead Redemption 2 – but the transformative nature of games has remained constant. Some of my fondest childhood memories involve me saving the planet from nuclear war in Atari’s Missile Command (1980). And steering scores of green-haired and blue-robed critters to safety in DMA Design’s Lemmings (1991). And fighting aliens and multi-coloured dragons in Sega’s Space Harrier (1985). And sending a certain moustachioed Italian plumber up and down dozens of oversized green pipes in Nintendo’s Super Mario Bros (1985).

After years of corporate giant dominance during the ‘90s and the ‘00s, video games industries entered what is considered a renaissance period of sorts, wherein independent game developers began to break the mould by stepping out on their own. Markus Persson’s 2009 open-world sandbox game Minecraft is considered by most to be the nucleus of the movement, and the likes of Braid, Limbo,Super Meat Boy and Journey were all developed by spirited, innovative and, crucially, self-publishing creators, shortly thereafter.

Over time, this indie renaissance paved the way for video games which consider a whole host of unlikely themes, including mental health. Fullbright’s Gone Home, for example, explores homosexuality through a series of coming-of-age diary entries. Lucas Pope’s Papers, Please tackles political hostilities through the eyes of a fictional Eastern-bloc immigration officer. The Stanley Parable questions the futility and the illusion of choice through the lens of the daily 9-to-5 grind. Actual Sunlight by Will O’Neill is a short interactive story about a dysfunctional 30-something man who struggles with love, depression and societal integration. Zoe Quinn’s Depression Quest is a narrative adventure that tasks players with managing mental illness alongside the tenets of everyday life – relationships, jobs and the daunting thought of seeking professional help. Vander Caballero’s Papo & Yo, on the other hand, is a semi-autobiographical tale that explores the emotional fallout faced by its child protagonist as a result of his alcoholic father. Eli Piilonen’s The Company of Myselfexamines the challenges of seeking professional help for the first time. Even unlikely big-budget video games, such as Fortnite and Grand Theft Auto V, are an equally vital part of the conversation, all of which I’ll be later exploring. The video games spectrum is as wide and vast and deep as the digital landscapes they so bountifully portray. Their huge and positive scope is limitless, and the ever-pervasive medium can inspire and delight, teach and inform, influence and impress.

* * *

Not everyone is as enthusiastic as I am. If you’re not familiar with many games from first-hand experience, you’ll almost certainly have seen/read/heard some media mogul’s opinion (emphasis on ‘opinion’) that video games are, on the one hand, for children, or – on the extreme other hand – create murderers. Starting with the less harmful end of the spectrum, depictions of video games in news programmes and conservative articles as child’s play diminishes their position as a credible source of conveying information. How you choose to enjoy video games is up to you – be it to switch off and relax after a long day with FIFA,meeting up with pals for a round of Call of Duty online, or to learn and explore with some of the games listed previously. But pedalling the common and longstanding idea that they’re reserved for basement-dwelling teenagers with bad skin and questionable hygiene is still one of the most common stereotypes. It’s not only condescending and archaic but also largely false. The average video game player is 35 years old and has been playing games for 13 or so years,7 and in 2018, the average Scottish player spent £415 on games, downloadable content (DLCs) – additional levels, character power-ups, cosmetic items etc – and virtual currency.8 Moreover, the largest single age/gender demographic of video game players in the UK is 15-24 year-old males – making up 14 per cent of everyone playing9 – which means that the video games medium has quite a different consumer base to what the stereotype-pushers say, and it is in a unique position to inform and educate around adult themes.

At the more harmful end of the spectrum, the mainstream media can have a damning impact on the societal perspective of video games – particularly when mental health issues are folded carelessly into the discussion. Here are a handful of negative but unfounded articles related to video games and mental health that inevitably perpetuates inaccurate stereotypes and causalities:

Did violent video game Call of Duty spark gun-crazed loner’s killing spree? Adam Lanza ‘spent hours with game just like Anders Breivik’ – Daily Mail Online (December 15, 2012)

Boy, 17, who was ‘tortured and buried in a shallow grave over a $500 dispute’ met the three teenagers accused of his murder via a medieval video game – Daily Mail Online (March 28, 2019)

Trump wants you to think about video games instead of guns – CNN (March 8, 2018)

Nut Cases’ wide swath of destruction / Oakland gang ran ‘wild,’ killing, robbing at random – SF Gate (February 10, 2003; within which the opening paragraph identifies Grand Theft Auto 3 as the root cause)

French terrorist played violent video game Call of Duty before embarking on brutal killing spree of seven, says wife– Daily Mail Online (June 1, 2012)

The first of these news stories spanning 15 years relates to the potential motives of Sandy Hook Elementary School shooter Adam Lanza in 2012. Within, the article names Activision’s long-standing military first-person shooter series Call of Duty as a video game that Lanza played regularly and contains insights from a man named Peter Wlasuk, a plumber who is said to have observed posters of military weaponry in Adam Lanza’s bedroom when visiting the Lanza household in Connecticut before the shootings.

The source’s only quote from Wlasuk within the story reads: ‘The kids who play these games know all about [guns]. I’m not blaming the games for what happened. But they see a picture of a historical gun and say, “I’ve used that on Call of Duty”.’ Which surely quite explicitly answers the question the article’s speculative headline poses.

The second article proposes that the three men charged with the kidnapping, torture and murder of Justin Tsang in Sydney, Australia in 2019 met within the online portion of Taleworlds Entertainment’s medieval role-playing game Mount & Blade: Warband (2010). The article posits those charged with Mr Tsang’s murder did so amid a dispute over $500 AUD. On the face of information contained within the news story, the details of where the men charged with murder met – be that in real life or via a video game – seems irrelevant.

The third article is Donald Trump talking bollocks, and while CNN adopts a semi-critical stance towards the US President, the headline is leading, bordering sensationalist.

Some of the claims in the fourth article, published in 2003, are false, not least the suggestion killing non-playable characters in Grand Theft Auto games scores the player points. The article then suggests a gang accused and charged of multiple murders were inspired by Rockstar’s enduring 18+ crime simulator series GTA. There is no evidence within the article to support this beyond its own conjecture.

The fifth and final article, somewhat similar to the first, attempts to explore the motives of another mass shooting, carried out by Mohammed Merah in the south-west of France in 2012. Here, the article posits Merah’s ex-wife, Miriam, to whom he was married to for 17 days, said the pair played violent video games together.

The article quotes Miriam Merah as saying: ‘We had many religious conversations, but we spent our time playing PlayStation, including Call of Duty and Need for Speed… we also watched The Simpsons together. We talked a lot and he needed someone to listen.’ At no point does the article suggest The Simpsons or racing game series Need for Speed played a part in Merah’s unlawful behaviour.

Of course, none of this should detract from the horror of the killings and criminal behaviour. The assertion that mature video games – those designed for adults aged 18 or above – glorify violence or encourage vulnerable people to commit anti-social behaviour any more than other modern media is irresponsible. It’s simply untrue. By questioning the mental state of the perpetrators while citing video games as catalysts, these inflammatory articles also serve to perpetuate the stigmas and stereotypes that surround mental illness and fear.

* * *

When I started writing about video games professionally, I would cite BioShock – a game which depicts unstable individuals in a crude and gratuitous, plot-serving manner – as my own unlikely nucleus for viewing mental health through the lens of video games. Irrational Games’ hit doesn’t claim to explore themes of mental health explicitly, but against my now very personal attachment to the shooter game, it did make me consider how video games portray sensitive subjects in and around the discussion, not least suicide. Challenge lies in separating the medium from ill-informed stereotypes. Like many facets of pop-culture media, video games can too often lean into the idea that mental illness is something to be feared. Frustratingly, this serves to accentuate societal stigma around issues of mental health, and more disheartening still, is the fact that this allegory suggests we should fear the unknown. This is an attitude that’s not only reductive by its very nature – why wouldn’t we instead strive to understand the unknown – but is also untrue in terms of mental health, with boundless literature and information out there to break the stigma of fear and allow anyone to engage and understand the topic better.

The starkest example of the ‘mental illness is unknown therefore scary’ trope is that there are a huge number of horror games set in asylums or psychiatric institutions. Remedy Entertainment’s 2010 action game Alan Wake is set in an asylum, as are Red Barrels’ 2013 survival horror Outlast and DreamForge’s 1998 point-and-click adventure Sanatarium. Psychiatric hospitals in various states of disrepair feature in several of Team Silent’s Silent Hill survival horror series (1999 – present), while Jyym Pearson’s 1981 eerie graphic adventure game The Institute is packed with dated and harmful parlance, even for its time. Access Software’s 1990 MS-DOS game Countdown provides some similarly obtuse mental health commentary, and Tecmo’s 2008 horror venture Fatal Frame 4 takes place within a decrepit sanitorium. Filled with unpredictable, almost always rage-filled baddies, these are a snapshot of the stereotypical portrayals of mental health institutions and also highlight the misconstrued relationship shared between mental illness and horror. People receiving treatment for mental health issues should not be degraded, far less feared, and their depiction as monsters – be that a metaphor manifest of ‘the unknown’, or because real world hospitals are associated with illness and death – is cruel, unnecessary and gratuitously misinformed.

Moreover, within these games, the psychiatric establishments in question are often abandoned, its patients are often non-playable enemy characters, their behaviours repeatedly unpredictable, and their nature is usually characterised by lazy traits such as subdued speech, erratic movements, anxious dispositions, and/or hostile tendencies. One of the first characters you meet in Sanitarium is a chap who repeatedly bangs his head against a concrete wall until his brow is visibly bleeding. In Outlast, journalist Miles Upshur spends the majority of his time wrestling with patients inside the game’s Mount Massive Asylum and being force-fed jump scares, unpredictable set pieces serve solely to shock players when they least expect it. And in Silent Hill 2, while Brookhaven Hospital is designed to underscore protagonist James Sutherland’s deteriorating mental state, it nevertheless regurgitates all of the aforementioned antagonistic stereotypes and clichés around the ‘criminally insane’ in the process.

Another distinction video games often struggle with in mental health terms, not exclusive to the horror genre, is the difference between suicide; heroic-suicide and heroic-sacrifice. The latter two are almost always tied to plot-progression, and likewise often overlap in a bid to paint their characters as martyrs, or at the very least, noble. In the 1998 Japanese role-playing game Suikoden, a Game of Thrones-style king by the name of Barbarossa Rugner gets possessed by an evil entity, rediscovers himself towards the game’s finale, and ends his own life to protect the world. Basically, Barbarossa heroically kills himself to salvage the lives of others.