7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Reardon Publishing

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

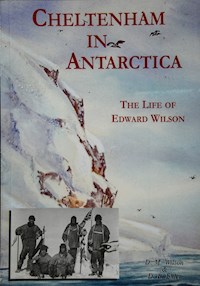

Edward Adrian Wilson is perhaps the most famous native son of Cheltenham. In the early years of the 20th century, he was one of the major influences and personalities of the heroic age of Antarctic exploration and has also been recognised as one of the top ranking ornithologists and naturalists in the UK during this period. He was also one of the last great scientific expedition artists. This is the illustrated story of polar explorer Edward Wilson, from his boyhood in Cheltenham to the diaries and letters associated with his last days as a member of Scott's ill-fated Antarctic expedition. All the royalties from this book will benefit the Wilson Collection Fund at the Cheltenham Art Gallery and Museums.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 246

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

CHELTENHAMINANTARCTICA

THE LIFE OF EDWARD WILSON

D.M. WILSON&D.B. ELDER

*****

Three mottoes have helped me and are good to live with:

Wilson motto - Res Non Verba (Do, and don’t talk);Cheltenham College motto - Labor Omnia Vincit (Work overcomes everything);Caius College motto - Labor Ipse Voluptas (Work is its own joy).

EAW*****

All of the royalties from this book will benefit the WilsonCollection Fund at the Cheltenham Art Gallery and Museums,which helps to preserve the Wilson Family Archive.

Published by

REARDON PUBLISHING

PO Box 919Cheltenham, GL50 9AN EnglandTel: 01242 231800

Email: [email protected]

Written and ResearchedbyD.M. Wilson & D.B. Elder

Copyright © 2012

Design and LayoutbyD.M. Wilson&Nicholas. Reardon

Walks RecreatedbyD.B. Elder

www.antarcticbookshop.com

Introduction

Edward Adrian Wilson is perhaps the most famous native son of Cheltenham. In the early years of the 20th Century, he was one of the major influences and personalities of the heroic age of Antarctic exploration and has also been recognised as one of the top ranking ornithologists and naturalists in the United Kingdom during this period. He was also one of the last great scientific expedition artists.

Despite this, remarkably little has been published about him. His father wrote an unpublished biography of him shortly after his death. This was an important source for George Seaver, who published three volumes of biography on Edward Wilson in the 1930s and 40s, fortunately quoting extensively from his letters and diaries. After the appearance of the first two volumes much of the source material that Seaver had used was destroyed, most of it on the instructions of Oriana, Edward Wilson’s widow. There was nothing malicious in this: she simply thought that she had done her public duty in allowing a biography to be published and did not want strangers digging around in her private correspondence after her death. In the 1960s and 70s, through the Scott Polar Research Institute, the Antarctic expedition diaries of Edward Wilson and a volume of his Antarctic bird pictures were published. Several people tried to write new biographies in the 1970s and 80s but all failed for the lack of new material: due to the subsequent events, George Seaver’s books and the published diaries already contained much of the source material about the life of Edward Wilson.

As such this volume draws heavily on the work of Edward Wilson’s father, on the published diaries, and on George Seaver. With Seaver in particular, however, his use of the historical sources available to him requires a word of caution: he frequently used the narrative technique of rolling quotations from several letters or diary entries into one quotation, passing them off as a single quotation from a single document. Since he published no footnotes it is almost impossible to establish where he has or has not done this, although his longer quotations, or quotations from complete letters, tend to be accurate. Unlike some commentators in subsequent generations, who often use quotation techniques to alter historical facts and to mis-represent what was said, with Seaver it is generally benign - he has not, as far as we have discovered, changed the sense of meaning, or mis-represented facts external to the actual form of the quotation. It is, however, something of a disaster from the point of view of accurate scholarship given that the original manuscripts are often no longer available. We have done our best, where possible, to find the original sources but these are very scattered, where they still exist, and it is painstaking work. Occasionally, they can be recreated through bringing together copied extracts - fortunately a habit in which many of the Wilson family indulged - such as in Edward Wilson’s last letter to Oriana, reproduced towards the end of this book.

In many ways, therefore, the following text should not be seen as a major new biography of Edward Wilson but rather as a complement to the volumes of George Seaver. This is not to say that there is no new material in the book, there should be enough to interest polar scholars, though there may not be as much as they had hoped. Where possible, we have also chosen to use previously unpublished illustrations from the vast collections of Edward Wilson’s pictures. These, alone, should be enough to interest those in search of new material. Our aim, however, is to meet the many hundreds of enquiries received about this famous son of Cheltenham and his life. Edward Wilson is one of the most asked after aspects of the collections at the Cheltenham Art Gallery and Museums. This work is intended to answer this demand from the public for something about Edward Wilson to be available to them in print, and to identify the ‘Wilson sites’ in and around Cheltenham, rather than to write an academic book. As such there are no footnotes but an annotated copy of the text will be placed in the collections of the Scott Polar Research Institute, the Cheltenham Public Library and the Cheltenham Museum, so that those who may be interested in the historical sources for this work will be able to find them.

Finally, it seems impossible not to say a few words about the contemporary situation as regards polar historical scholarship and biography, against which this book will inevitably be judged by some. We hope that this work is an exception to the current fashion for cynicism. Some will doubtless find it an “old fashioned” or “non-critical” work as a result. For this we make no apology. Our aim isn’t to pick for faults like vultures at a carcass, nor to sit in judgement, but to help you to get to know a remarkably complex man a little better - and maybe - just maybe - you will find a little inspiration for your own life and times through the life and times of Edward Adrian Wilson.

D. M. Wilson and D. B. Elder

Authors’ Notes:

In keeping with the historical period, all units of measurement are given in imperial values with the metric conversion following in brackets. Unless otherwise stated, distances within the biographical text are given in geographical (or nautical) miles. One geographical mile is equivalent to 1.15 statute miles or 1.85 kilometres. In the Wilson Walk maps at the end, regular statute miles are used.

In keeping with Edward Wilson’s lifetime habit of annotating books, letters and his diaries with sketches and with private thoughts summarising meaning, we have chosen to insert some of his sketches - or occasionally details of larger pictures - into the text and to start each chapter with an extract from his writings, which we hope will give some appropriate reflection of his thinking.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the considerable kindness of the numerous individuals and institutions that have assisted in the production of this book in many different ways. If we were to acknowledge everybody who has helped us it would fill a small book in itself - but we are genuinely very grateful to you all, particularly those hard pressed individuals in under-funded public institutions whose time is always over-stretched. We would also like to thank the numerous individuals and private collectors who have permitted us to reproduce material from their collections, whether through the use of quotations or the reproduction of pictures. In a similar vein, we also wish to thank all of the following institutions for their permission to reproduce material from their collections: The Scott Polar Research Institute, Cambridge (SPRI); Cheltenham Art Gallery and Museums (CAGM); Cheltenham Public Library (CL); The Headmaster, and the Cheltonian Society, of Cheltenham College (CC); The Master and Fellows of Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge; The Natural History Museum, London (NHM); and the publishers, John Murray, for permission to use material from the biographies of Edward Wilson by George Seaver.

In addition the following individuals have helped us enormously by reading parts of the text and giving their advice: R. K. Headland F.R.G.S. the Archivist and Curator at the Scott Polar Research Institute; Dr S. Blake, Keeper of Collections at the Cheltenham Museum; the polar historian, D. E. Yelverton F.R.G.S.; D. C. Lawie F.R.S.A.; and Mrs A. Elder (née Gauld). We would also like to thank Mrs S. Pierce and Mrs E. Gemmill for their hard work, particularly as regards reading the proofs. Needless to say, none of the above are responsible for the contents of the book in any way.

Finally, we would like to acknowledge the long sufferance of our immediate families, Meg, Rachel, Catrin and Duncan - who supported us all the way.

1. “A Queer Little Character”

*****

Love one another in Truth and Purity, as children, impulsively and uncalculatingly…EAW

*****

Tuesday 23 July 1872 dawned warm and cloudy in Cheltenham. At number six Montpellier Terrace, the serenity of the day was punctuated by the fuss of the midwife and house servants. Here, in the large front bedroom on the first landing, was born the second son and fifth child of Edward Thomas Wilson and Mary Agnes (née Whishaw). The expanding family of a local physician, if an influential one in local civic life, drew little comment in the press. They were more concerned with the thunderstorms and floods which were to deluge Cheltenham in the ensuing days. Yet nearly 41 years later, at the news of his death, the name of this child, Edward Adrian Wilson, would be known across the length and breadth of the British Empire and beyond.

He was born into a flourishing family, full of strong, colourful characters, with a typically Victorian sense of the family and its lineage. On his father’s side the Wilson family stretched back into 17th century Westmoreland and descended from a long line of Quakers, although there hadn’t been a Quaker in direct descent for three generations by the time Edward Adrian was born. The last had been his great grandfather, Edward Wilson of Liverpool and Philadelphia (1772-1843), who had made a fortune through land in America and the birth of the railways. He was a friend of George Stevenson’s, a director of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway and one of the few people to successfully reclaim lands in the United States after the War of Independence. The children inherited fortunes and wrote ‘Gentleman’ as their occupation; they were inveterate collectors and were major benefactors of public institutions on more than one continent. They were fascinated by the world around them. Edward Wilson of Hean Castle (1808-1888) (‘Grandfather’) was one of these. He brought together what was reputed to be one of the finest collections of hummingbirds in existence. He became High Sheriff of Pembrokeshire in 1861 and was a widely respected landowner. A series of poor investments meant that the next generation did not inherit fortunes but were merely wealthy, becoming adventurers and pioneers. Two of his sons (‘Uncle Henry’ and ‘Uncle Rathmel’) spent time in the Argentine where one lost an eye to a lasso. Another son, Major General Sir Charles Wilson (‘Uncle Charlie’), rose to become a famous explorer of the Middle East and was a key figure in the attempted rescue of Gordon from Khartoum. His books are in print to this day. The eldest son, however, who was to become known to subsequent generations as ETW, was known to Edward Adrian simply as ‘Dad’. Edward Thomas Wilson of Cheltenham (1832-1918), was a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians. He had declined fame and fortune in the London hospitals, choosing instead to become a general practitioner and consultant in Cheltenham from 1859. Here he pioneered modern medical practices, such as clean drinking water, isolation fever hospitals and district nurses. He was President of the local Natural Science Society and helped to found the Delancey Hospital and the local Municipal Museum.

On his mother’s side, the Whishaw family stretched back into 16th century Cheshire and descended from a long line of successful lawyers and businessmen. This branch of the Whishaw family had made its home amongst the expatriate English community in St. Petersburg with many connections, and rumours of blood ties, into the Russian Imperial House. His grandfather Bernhard Whishaw (1779-1868) married Elizabeth Yeames (1796-1879), also from a powerful expatriate English family in St. Petersburg. Having founded one of the most successful Anglo-Russian trading companies, they moved to Cheltenham around 1850. Elizabeth went to great lengths to dominate Cheltenham Society. Many of the family (uncles and aunts) stayed behind or returned to reside in Russia. Here, amongst the English expatriate trading community, they enjoyed the personal protection of Tsar Nicholas I during the Crimean War and would take evening strolls with him along the quays of St. Petersburg. They spent the summers in their country Dachas hunting and fishing; an association and way of life that was brought to a close in 1917 when some of them would flee from the Russian Revolution through Norway and travel past a monument to the memory of Edward Adrian. The youngest child of Bernhard and Elizabeth, however, came with them to Cheltenham at the age of seven and lived there for the rest of her life. Mary Agnes Wilson, née Whishaw, (1841-1930) was energetic and forthright. A good horse rider and a keen gardener, she also enjoyed painting and reading theological books. More importantly, perhaps, she was a respected authority on the breeding of poultry, the first to import and breed Plymouth Rocks from America and the author of the ABC of Poultry (1880), which was considered a definitive work for many years. She was known to Edward Adrian simply as ‘Mother’.

This was the sort of family that hired a shop window to watch the first motor cars race through Cheltenham at eight miles an hour. Moreover, it was figures such as these who filled the family stories of Edward Adrian’s childhood. Tales of Empire, exploration and wild adventures in the far flung corners of the globe widened his eyes with impish delight. It gave him the inheritance of an enquiring mind, the inspiration for living life to the full and the privilege of a strong sense of belonging. It was also figures such as these who gathered at the home of his paternal grandparents on 16 September 1872 for his baptism. He was baptised by Canon Stephenson in St. John’s Church, Weymouth: Edward, after the line of his paternal forebears and Adrian after a relative on his paternal grandmother’s side. In the family, however, he became universally known as Ted.

With deep red hair and a ready smile, Ted was regarded by his mother as “the prettiest of all my babies”. At eleven months he could take steps alone and was soon running and climbing over everything, speaking his first words (“papa” and “mama”) and spreading mayhem in the wake of his violent outbursts of temper. His parents nevertheless took their traditional one month holiday away from the family during the summer of 1873, leaving the children in charge of the nurse, and on this occasion visiting family members in Russia. At Christmas, Ted joined his older siblings in the family tradition of the singing of carols for their parents whilst they prepared for Church. Later, Father Christmas appeared, as he did every year, following the unfortunate calling away of ETW on ‘an urgent medical emergency’. Ted received the gift of a model farmyard and a trumpet, with which he doubtless continued his terrorisation of the nursery.

During this period the Wilson family was still growing, both in physical numbers and in stature, with ETW’S growing reputation as a physician. Both led to the requirement for a larger house. In September 1874 they moved around the corner to Westal on Montpellier Parade. Westal was a large, detached ‘Regency’ house, with a private carriage sweep, large gardens and stabling, greenhouses and ferneries, marble fire places, four reception rooms, ten bedrooms, a nursery and servants’ quarters. The requirements of the household meant that five servants were employed in the house alone - not untypical of the period. With Westal they inherited ‘Tom’, a large grey cat with a severed tail, “a redoubtable mouser and general family pet”. The story was that he had been a favourite cat at Dowdeswell Court, so his tail was cut off in order that the gamekeeper might recognise him and spare his life.

For many years, and for all Ted’s life, Westal was the Wilson family home. It was here at the age of three that he gave performances of Ding, Dong, Bell and gave “a profound bow” when dancing Sir Roger de Coverley for visitors. It was here that he was first noted to be “always drawing” which resulted in his mother giving him some drawing lessons. By four years of age he was “…never so happy as when lying at full length on the floor and drawing figures of soldiers in every conceivable attitude”. Many of these drawings started to be collected into scrap books at this time. His father noted that:

Toy soldier

He learns little and cries oft but never tires of drawing his soldiers, funny little figures full of action and all his own, for he disdains the idea of copying anything.

It was the emotional contradictions of Ted’s constitution, however, that most exercised his parents during this period. Both of them thought him “a queer little character”. In part, perhaps, this was due to the difficulties of life in the nursery. Life was not always easy during the Victorian era, even for the upper-middle classes. In 1876 Ted’s younger sister, Jessie (Jessica Frances), died, giving him his first experience with death at a very early age. Yet these inherent contrasts that appeared in Ted seem to have been fired by such a passionate intensity that they went beyond the expected range of expression in small children. On the one hand he could be generous and kind, almost to a fault, with loving arms placed around his siblings or parents, followed by a big kiss. Yet at other times he was fiercely independent. He was prone to wandering off on his own “to explore” from quite a young age. At the age of five, he toddled off alone across the moor near to Borth and when found explained that he was going for a walk and would return when he felt tired. On another occasion, when visiting Aberystwyth, he got lost. A frantic search found him crying on the knee of a local cobbler just as the Town Crier was about to be summoned. Ted was also full of laughter and fun, yet prone to fits of earnestness during which noone could make him laugh. On these occasions he would make odd and sometimes profound comments for his age. Further, whilst he was generally noted to be of a sweet temperament he frequently exploded in violent outbursts of temper. He often showed unusual bravery and maturity, yet was always ready with floods of tears. “The least thing,” was said to make him cry. On one occasion, his punishment was to be dressed in his sister Polly’s clothes and stood on a table. This pendulum of contrast was to be carried out of the family home and into school.

Pirate

Ted started lessons in 1878 with a Governess, Miss Watson, who found him clever but boisterous. The following year he went to join his older brother, Bernard, at Glyngarth School, a purpose built Preparatory School considered to be a model of excellence by the school examiners. His father thought him “in his element” when fighting with boys from a rival school, ‘the Austinites’, on his way to and from school.

The family habit of taking long walks in the countryside, often of ten miles or more, soon started Ted on the lifelong habit of collecting objects which interested him. With his father as his guide these walks, in the Cotswolds that surround Cheltenham, in the nearby Malvern Hills, or on long summer holidays by the sea, started to yield a bountiful fascination with the natural world. He started by collecting fossils and butterflies, then went on to feathers but soon moved on to “anything he can lay his hands on”. His drawings, however, still focused mainly on soldiers and battles - primarily inspired at this time by the Zulu War. On one ten mile walk across Minchinhampton Common, near Amberley,

Butterfly

“… the children enjoyed the fine bracing air… where their Zulu hats went careering over the plain in a high wind.”

From September 1879 the countryside came slightly closer to home. His mother took on a little farm, Sunnymede, on the outskirts of Cheltenham, near Up Hatherley, where she could breed her poultry and practice “scientific farming”, whilst the children could keep farmyard pets. Much of the produce was consumed in the household or sold in the local area, although it was never very profitable. The farm produced over 40 varieties of apples and pears, amongst other crops, which were often shown in local agricultural shows. It was not all plain sailing; on 7 July 1884 Mary Agnes lost 46 prize chickens from a coop. A policeman was called but it was soon found to be the work of a fox. Mostly, however, the farm and its produce were a source of great pleasure and pride.

It was this Gloucestershire countryside, full of birds, beasts and flowers that inspired the young boy more and more. At the age of nine he announced to his father that he was going to become a naturalist. His mother noted that he would rather have a naturalist’s ramble with his father in the countryside than enjoy the games of the playground. Although good at sports, in which he often carried off prizes - even captaining the school 2nd XI - they never truly excited him. Nor did his lessons. Although he was considered a bright pupil, his reports were usually rather a disappointment; his high spirits and mischievousness dosed with a good streak of stubborn determination to be independent meant that they were often full of the word “refuses”, so much so that he sometimes had to forfeit his shorter school holidays to catch up with the work, under the despairing gaze of his mother. Unusually, perhaps, for a pupil who apparently delighted in disruption, his teachers were moved to comment on his unusual honesty. They could, they said, “always trust Ted’s word”. Much to the relief of his parents, his crying fits and temper tantrums ceased as he entered double figures.

During the early summer of 1883, at the age of 11, he took his first lessons in taxidermy “from White, the bird stuffer”, his first subject being a Robin. At this point too, his art-work moved more and more to recording the natural world around him. Some of the last of his soldier drawings show his imaginative reconstruction of the Battle of Tel-el-Kebir (1882), where Uncle Charlie was engaged with the British army campaign against the Egyptians. Meanwhile, he was starting to show more evidence of applying himself at school. So much so, it was thought that if he was given special tuition he might be able to pass a public school scholarship. So it was that in the autumn of 1884 Ted was sent away from Cheltenham to Clifton in Bristol, to a preparatory school set up in the shadow of the famous Clifton College and run by Mr Erasmus Wilkinson. Here is where the underlying tensions of his character which had emerged during the first twelve years of his life would begin to be moulded and fused from their adverse expressions and into character strengths.

Soldier

Edward Thomas Wilson (ETW)

Mary Agnes Wilson

The new arrival Edward Adrian Wilson 1872

“The prettiest of my babies” Ted in 1873

Ted c1876 at around 4 years

Ted c1884 at around 12 years of age

2. “A Splendid Place for Bonnie Beasties”.

*****

Every bit of truth that comes into a man’s heart burns in him and forces its way out, either in his actions or in his words.Truth is like a lighted lamp in that it cannot be hidden away in the darkness because it carries its own light.EAW

*****

Erasmus Wilkinson was a 35 year old private tutor from Marlborough. With his Yorkshire wife, Constance, his sister Mary and the help of three servants, he ran a small Preparatory School at Clifton for a dozen boy boarders. The school expected high standards from its pupils both on the academic and personal levels. It also had a higher level of tolerance for the vagaries of teenage boys - at least in so far as these were channelled into scientific exploration - than was normal for the period. As a result the schoolroom exploded with everything that the boys could find: silkworms and mice; newts and snakes; redpolls and beetles - “a regular menagerie”, his father thought. It suited Ted perfectly. The schoolwork, however, came as a bit of a surprise to him, he was no longer allowed to “stare about a bit in schooltime”. He wrote home to his father:

Lizard

I have got on so far pretty well with my books, but it is hard to settle into new books after using the same for five years. I am doing my best though and shall soon get accustomed to the work.

Ted was intensely keen to do well in this new environment - so much so, that he sat with his back to his pets to concentrate fully upon his lessons. The supply of these school pets seems to have caused some consternation amongst the local populace, particularly when mixed with the Wilson family disposition for teasing and practical jokes. His future brother-in law recalled:

… [we] went over the downs to see him at school and true to the family traditions we took him what we knew he would love, a big tin pail of newts from Cheltenham, which we much enjoyed in the train allowing them to crawl about and horrifying the passengers who held the old belief the orange ones were poisonous.

It was in the atmosphere of his new school, which deliberately set out to foster the moral fibre of its boys, that the contrasts and deep sensitivities of Ted’s highly strung character began to coalesce. Comment was made on his exceptional sense of good sportsmanship and his courteousness. This not only extended to his fellow pupils, staff or family members; he found it increasingly difficult to accept wanton destruction in himself or others, even in the name of boyhood or science. Unusually for a collector of the Victorian era, he would never take more than one egg in four from the nest of a bird and encouraged others to follow his example. To take more from a nest became, in his eyes, mere robbery. This love of the natural world developed in him a strong sense of responsibility. On one occasion he wrote in a letter home:

I caught a mouse by the hind legs this morning and as they were rather hurt I took it out for a walk and deposited it among some dry leaves near a house in the hope that it might find its way in.

This empathic concern, combined with his courage and independence of thought, merged with his scientific inclination during his early teens and launched him on a life-long path of struggling with Truth. He constantly wrestled throughout his life with its high ideals which he was taught at home, at school and in Church. These truths he attempted to incorporate into his own life, whether this required discipline on the scientific, artistic, moral or any other plane. It was this honest consistency at all levels of his life that was to earn the future respect of many of his fellows; but it was not attained without a great deal of hard work. Neither, however, did he ever become sanctimonious; his rich sense of humour would not allow for that. Further, the difficulties which he struggled to overcome in himself he could hardly condemn in others. Every new proposition that was presented to him was taken on merit and tested against his hard earned experience. He jettisoned those aspects which were entirely useless, merely hypocritical pietism, whether academic, ethical or religious, and incorporated that which was practical in responsible every day life. Perhaps the most remarkable thing about this process, however, was that very few people knew what was going on inside the mind of the jolly schoolboy, or later of the man. Ted was generally self effacing and was happy to simply do his best whilst staying in the background. This was deeply reminiscent of some of his illustrious Quaker ancestors. His Great Uncle, Thomas Wilson, had devoted his life to science, was a mainstay of the Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences and founded the Entomological Society of that city. Despite giving 28,000 specimens, 11,000 books and £5,000 to the Academy, when he found he was to be publicly thanked for his donations, he instructed them to desist or they would receive no further gifts. Whilst Ted was at Wilkinson’s school, this process of struggling with truth was still emerging within him. It found expression in one way through his increasing scientific accuracy - his father was greatly impressed that Ted’s beetle collection now had the males and females appropriately labelled - and in another way in the pleasure which Ted took in living on less pocket money than his parents allowed.