Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

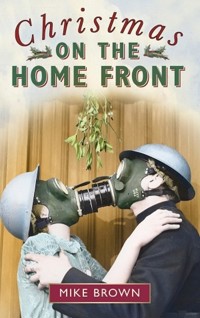

The outbreak of war in 1939 saw the disappearance of many traditional British celebrations. Guy Fawkes' Night went immediately – gunpowder production was needed for the war effort and bonfires contravened the blackout. Summer holidays became a thing of the past and Easter all but disappeared as chocolate – and even real eggs – went 'on the ration'. In spite of this the nation remained determined to celebrate Christmas as a time of family and community; a time when war could be set aside, if only for a day. Drawing upon personal recollections, contemporary Mass Observation reports, newspaper articles, advertisements, and personal and archive photographs, Mike Brown looks at each wartime Christmas on the British Home Front, from 1939 to 1944. He explores how people celebrated Christmas despite the problems of shortages, rationing, the blackout, Luftwaffe raids and the absence of family members who had been called up or evacuated. Life in Britain changed dramatically as the war progressed; the annual celebration of Christmas provides fascinating yearly 'snapshots', illuminating the changes over six years of conflict.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 262

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2004

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Christmas

ON THE

HOME

FRONT

MIKE BROWN

THE HISTORY PRESS

First published in 2004 by Sutton Publishing Limited

Reprinted in 2007

The History Press The Mill, Brimscombe Port Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL52QGwww.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved © Mike Brown, 2004, 2013

The right of Mike Brown to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 9548 4

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1. 1939: The First Wartime Christmas

Christmas Among the Evacuees

2. 1940: The Second Christmas

The Christmas Raids

3. 1941: The Third Christmas

Christmas in the Countryside

4. 1942: The Fourth Christmas

Christmas Weddings

5. 1943: The Fifth Christmas

Parties

6. 1944: The Last Wartime Christmas

Postscript

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

I would like to take this opportunity to thank the following people who so kindly shared their memories with me: Grace D., Dorothy Adcock, Arnold Beardwell, John Bird, Jackie Burns, Margaret Cordell, Margaret Cushion, Jenny D’Eath, Brenda Dudley, Bryan Farmer, Paul Fincham, Georgina Foord, Raymond Gibbons, Robina Hinton, Mrs Elizabeth Hobson, Mrs Janet Houghton, Doreen Isom, Doreen Last, Joan Letts, Roy Littler, Nita Luce, Norman Mallins, Brian Martin, Patricia McGuire, John Middleton, Sybil Morley, Grace Newman, Grace Newsom, Mike Owen, Margaret Peers, Wendy Peters, Yvonne Pole, Roy Proctor, Ernie Prowse, Betty Quiller, Lily Roberts, Doreen Robinson, Vera Rooney, Mrs Sewell, Vera Sibley, L.E. Snellgrove, Margaret Spencer, Eric Stevens, Les Sutton, Mrs B.W. Thomson (who kindly loaned the photograph on page 134), Mrs C. Thomson, Elizabeth Toy, W.J. Wheatley, Edith Wilson, Mrs D. Wilkins and Donald Wood.

Photographs: Associated Press 76, Crown Copyright 44, Empics 104, Hulton Archive/Getty Images 97, Lewisham Local History Unit 160, London Metropolitan Archives 4, 31, London Transport Museum 73, 165, N.I. Syndication 20, Radio Times 58, 69 99.

Photographs and illustrations from contemporary publications: Aero Modeller 122, The Beano (courtesy of D.C. Thompson & Co. Ltd) 39, Columbia Record Guide 158, Daily Herald 176, Daily Mirror 80, Film Pictorial 153, Gifts You Can Make Yourself 177, 178, Good Housekeeping 47, Home Notes 33, Illustrated 125, Kent Messenger 51, Landgirl 162, MotorCycling 107, 132, 138, Needlewoman & Needlecraft 124, Punch 92, Sunday Dispatch 38, 41, Woman & Home 45, 54, Woman’s Own 17, Women’s Pictorial 13, Woman’s Weekly 156.

Finally I should like to thank the following people who have been so helpful to me: Nina Burls of the Royal Air Force Museum, Hendon, Ben Howard of the Sayers Croft Evacuation Group, and Matthew Ray of the Shaftesbury Society, my editor Clare Jackson, and as ever, William, Ralph and Carol.

Introduction

The nation has made a resolve that, war or no war, the children of England will not be cheated out of the one day they look forward to all year. So, as far as possible, this will be an old-fashioned Christmas in England, at least for the children.

Ministry of Information short film, Christmas under Fire (1940)

When war broke out in September 1939 it was not uncommon, once again, to hear the remark, ‘It’ll all be over by Christmas!’ Actually there would be six Christmases before it really was ‘all over’, and in the interim the war would bring about the disappearance of many traditional British festivals. Guy Fawkes’ night went immediately: all gunpowder production was needed for the war effort and bonfires contravened the blackout. Summer holidays became a thing of the past in 1940 as total war, and Lord Beaverbrook, demanded ever-increasing production. Easter eggs became rare when sugar was rationed and disappeared altogether with sweet rationing. This left Christmas.

One of the biggest problems encountered in any attempt to study Britain during the war can be summed up in the phrase ‘regional variations’. Make any statement about food or Civil Defence and you will receive a barrage of responses along the lines of ‘it wasn’t like that where I was!’ The availability of food, for example, varied tremendously, with the countryside generally faring much better than the towns, and for many, mainly in the towns and cities, bombing was a common experience, whereas some rural areas never saw an enemy bomber. Some people saw it as their patriotic duty to follow all the rules and advice issued by the government, while others took a far more fatalistic view: eat, drink and be merry for tomorrow we die! Christmas, however, was one of the few unifying experiences of the war: a festival that was celebrated throughout Britain, in the towns and the countryside, and by rich and poor alike. True, in Scotland as a whole, Hogmanay was a far more important event, probably more so even than today, yet Christmas was also celebrated.

It also has to be remembered that the divide between rich and poor was much bigger in the 1930s and ’40s. Make do and mend was, for many families, nothing new; only the middle and upper classes saw such scrimping as a patriotic wartime duty. For many others it had always been a way of life. And we should not overlook the fact that the home-front experience changed as the war went on. Christmas, as a regular fixed event, throws into vivid contrast the changes which happened during the five years of war.

Of course, wartime Christmases need to be looked at from the perspective of their 1930s predecessors: there were fewer presents, a much shorter run up and holiday, and goose was still the traditional main dish. Mike Owen remembers: ‘On Christmas morning Mother would have been up at 6am to begin the preparation of the goose. The pudding took several hours of steaming, the kitchen walls would drip with condensation.’

To demonstrate how Christmas changed over the course of the war the book is divided into six main chapters covering consecutive years. Each of the first five chapters also includes a section on a particular topic, such as wartime weddings and Christmas among the evacuees.

ONE

—— 1939 ——

The First Wartime Christmas

Christmas 1939 was in many ways like a pre-war Christmas. There were, of course, emergency restrictions in place that affected the seasonal festivities, particularly the blackout regulations which made the traditional sight of Christmas trees decked with coloured lights, glimpsed through street windows, a thing of the past. One advert ran: ‘As dusk falls, the fairy lights on the Christmas tree outside St Paul’s Cathedral will go out … we must await Victory to again see them at night in all their colours.’ The delights of Christmas shopping were somewhat muted as the classic Yuletide shop window displays were unlit by night and obscured by anti-blast tape by day. Shopkeepers complained loudly that the blackout restrictions were curtailing trade, and on 2 December the Ministry of Home Security approved a device to help them. It took the form of a light in a special container, which threw its illumination either up or down and inwards, illuminating shop window displays without casting reflections in the street.

Window-shopping wasn’t the only thing affected by the blackout. In the four months between the outbreak of war and the first wartime Christmas around 4,000 civilians were killed on the roads, compared with just 2,500 for the corresponding period in 1938. And this was despite petrol rationing. On 3 September it had been announced that each motorist would be allowed between 4 and 10 gallons of petrol a month, depending on the horsepower of their car, beginning in that month. In December accidents claimed 1,155 lives, the highest figure since records were kept. In Birmingham the number of accidents was up by 81 per cent, while in Glasgow the figure trebled. The government, however, remained adamant that this was all the fault of stupidly careless pedestrians.

CHRISTMAS DAY BLACKOUT TIMES

London5.23 p.m.to8.37 a.m.Aberdeen4.589.18Belfast5.319.17Birmingham5.268.49Bristol5.338.47Cardiff5.378.48Edinburgh5.119.14Glasgow5.169.19Leeds5.18 p.m.to8.54 a.m.Liverpool5.268.59Newcastle5.119.02Penzance5.518.53Plymouth5.478.46These were the precise times given for 1940 and 1943, but in other years there was little variation.

During the ‘Phoney War’ the blackout was a constant reminder to the civilian population that Britain was at war.

Money was tight. In order to raise the £2 billion towards the cost of the war, the Chancellor, Sir John Simon, had introduced his War Budget on 27 September. This raised the standard rate of tax from 5s 6d to 7s 6d in the pound, at the same time reducing the married man’s allowance and imposing a 10 per cent increase in estate duty. It was expected that, for the nation’s sake, everyone would grin and bear increases of 1d a pint on beer, 1s 6d a bottle on whisky, 1d a packet on cigarettes, 2s per lb on tobacco, and 1d per lb on sugar, with the cost of all these increases being borne entirely by the consumer. All trades benefiting from the war were to pay an excess profits tax of 60 per cent; this was partly in response to the public outcry at the huge price increases that had quickly followed the declaration of war, and partly in an attempt to crack down on the type of profiteering that had been rife in the First World War. Actually, after an initial steep rise the prices of most goods had quickly fallen again, almost back to normal, but as an extra guarantee the Chancellor undertook to subsidise certain essential commodities, such as bread, flour, meat and milk, in order to keep down prices. Yet in spite of this, the various tax rises meant hefty cuts in the amount of disposable income available to most, even for teetotal non-smokers.

The weather was very seasonal. Most of Britain, indeed much of western Europe, was carpeted in deep snow during a very cold December, which was followed by the coldest January in Britain for nearly half a century. An 8-mile stretch of the River Thames froze between Teddington and Sunbury, and the Serpentine Swimming Club’s annual Christmas morning handicap had to be postponed as ‘there was too much ice to permit the holding of a race under fair conditions’. Ada Pope of Margate described how ‘the frost made the country look like a Christmas card’, while William Dudley wrote:

It was cold. Frogs in ice-bound pools were having a cushy time compared with us. All brass monkeys were carefully transported inside and kept near the fire. The trees bore a load of ice. Even the grass stems were icicles. And to add to it all there was a fuel shortage.

The war news was good. The universally expected and much-feared mass raids by Göring’s Luftwaffe had failed to materialise; rather than the hundreds of thousands of deaths that had been anticipated, in fact, by Christmas not a single British civilian had been killed by enemy bombing. What little German air activity there was, had been confined to Scotland; during December there had been attacks along the Firth of Forth on the 7th and the 22nd. There had also been some mine-laying activities around the south and east coasts of England.

Winter 1939 was the coldest for nearly fifty years, with widespread blizzards. These London evacuees are making the most of the snow in Hastings, January 1940. (Courtesy of London Metropolitan Archives)

Much of the foreign war news concerned the small Finnish army’s stout defence against their vastly superior Russian opponents, but the newspapers also covered the arrival of various Commonwealth troops. There were flight crews from New Zealand, and troops from Cyprus (who had arrived in France), while in the week before Christmas the papers described the arrival of the first Canadian troops in Britain. At sea the Royal Navy was fighting in the Battle of the Atlantic: on 17 December the crew of the Graf Spee, one of Germany’s new pocket battleships, had chosen to scuttle its vessel in Montevideo harbour rather than face the pursuing British ships.

For many households the Christmas celebrations were muted by the fact that so many people were absent. Fathers, brothers and sons were all serving their country somewhere in France: indeed, almost ½ million men were on active service by Christmas 1939. Sybil Morley’s father was the rector of a very scattered country parish in Essex, about 7 miles from Colchester, a garrison town. She recalled:

Early wartime Christmases were spent surrounded by soldiers – there was an invitation to them to come and spend Christmas afternoon with us. We always went to church first of course, and we children were allowed to take one present with us.

In the afternoon the soldiers arrived. Some came by taxi, some cycled and some even walked. They all seemed to enjoy being in someone’s home, chatting and eating whatever my mother could provide for them.

The government was keen that this should be a happy Christmas, in spite of the war. With puritanical zeal cinemas, theatres and other sources of entertainment had been shut down or had their opening hours restricted in the first few days of the war, but this was soon seen as a morale-sapping disaster. The authorities would not make the same mistake about Christmas; of course over-indulgence was to be discouraged, but people needed to know what they were fighting for, and Christmas, with all that it implied about tradition, family values, faith, neighbourliness, community, even peace on earth, was just the thing. Magazines, newspapers and radio articles all stressed the point.

In an article in Woman’s Own on 23 December Rosita Forbes argued that making this a good Christmas was almost a duty:

Remember there are lots and lots of happy Christmases ahead. You can be utterly sure of that … We’re all working, you see, for the same great purpose and it is just as much as a crusade – against nations which have no use for Christmas because they have ‘abolished God’ – as that which Christ fought for us … Your faith, your laughter and your certainty of good in the end, can make this Christmas as happy as any other … There is only one front. We’re manning it shoulder to shoulder. When the war is won, the effort of every woman – yours and mine and your neighbour’s – will have contributed to the victory … Let’s have all the ammunition for the Christmas front that we can afford.

But not everyone was in the mood for a happy Christmas. The editorial of the Guider magazine that December began:

So many people have said to me lately that they could not bring themselves to think of Christmas, not only because, this year, for many of us Christmas must be a reminder of other happier times, not only because many of us will be alone among strangers, separated from our families, anxious about people we love who may be in danger, but for a bigger, more unselfish reason. They cannot bear to think of Christmas because this year so much that they believed in has been broken.

Woman’s Own addressed the point about absent friends and family:

Are you looking forward to Christmas? Yes I know, in some ways it’s going to be awfully different; but it is going to be Christmas perhaps more than ever before … For instance, I expect a good many of you won’t be able to see the people who matter most to you this Christmas-time. And there’ll be a corner in your heart that has an ache in it – but ‘he’ or ‘she’ or ‘they’ whom you miss have it too, and that brings you closer together. And you are both determined to make Christmas as cheery as possible for the people you do see.

As yet there was no food rationing. Many people remembered the serious shortages that had developed in the First World War, and there was general concern about profiteering. At first there were a few shortages, which the government addressed by a scheme known as ‘pooling’. All supplies of certain items such as petrol and butter had to be put into a ‘pool’, and sold as a single, and therefore more controllable, product, using names such as ‘national butter’. Some people had already begun hoarding various items, and the government was not quite sure how to react to this. Certainly, if people were to lay down a small store of food to counter any future disruption of supply this would, within reason, be a good thing, as it would help to minimise the disruption caused. Yet at the same time over-storing would in itself cause shortages, which would bring about panic-buying and profiteering. The public were advised to lay in a small store, and were even given lists of appropriate goods, yet this could not fully control the issue. The fear of missing out, or of not providing properly for your family, especially when other people were known to be amassing large stocks, drove many who could afford it to get what they could, especially if there was a hint that this or that item would soon be unobtainable.

In October the newspapers had speculated that meat and butter would soon be rationed. Eventually the government bowed to the inevitable and on 29 November the Minister of Food, W.S. Morrison, announced that the rationing of butter and bacon would commence on 8 January, and in the meantime self-discipline and restraint were the order of the day – officially. But since people were aware that rationing would be introduced just after Christmas, few took any notice. Most took the opportunity to splurge before rationing was introduced; hotels were fully booked over the festive season, as were restaurants. Woman’s Pictorial magazine spoke for many: ‘One of the best things about Christmas is all the lovely things we have to eat – a greedy thought perhaps, but I think it is one that most people have. Why we don’t have plum puddings, turkey and mince pies at other times of the year I don’t know.’ A Stork margarine advertisement from that Christmas read: ‘What if there is a war on? Christmas parties mustn’t be called off on that account! There’ll be your men on leave to be entertained, your National Service workers needing relaxation. And cooking won’t be difficult – not now you can get Stork again, as much of it as you want.’ It went on to give recipes for Christmas trifle and mince pies, using ‘wartime mincemeat’.

Many Christmas recipes published in women’s magazines that December would soon seem lavish as shortages and rationing began to bite. Typical of this extravagance was the recipe for Christmas pudding printed in Woman’s Weekly. The ingredients for this included sugar, suet and margarine, all rationed in 1940, and egg, milk and dried fruit, all put on distribution schemes in 1940 and 1941. Even the breadcrumbs and flour would have to be National Wheatmeal after 1941. The following recipes, both from 1939, should be compared with ones from later in the war to show how deeply rationing was to affect Britain.

As yet rationing had not been introduced. Once it had, many recipes from this period would soon seem lavish. (Woman’s Weekly)

WARTIME MINCEMEAT

1lb raisins, stoned and chopped

1lb sultanas, cleaned

1lb currants, cleaned

½lb Stork margarine, melted

1lb apples, peeled and grated

1lb candied peel, chopped

2 nutmegs, grated

½lb demerara or granulated sugar

rind and juice of two lemons

Mix all the prepared fruits together, add the grated nutmeg, lemon rind and juice, and the sugar. Melt Stork and stir into the mixture. Stir well, put into clean, warm jars, and tie down securely. This quantity makes about three 2lb jars.

Stork Margarine advertisement

Woman’s Own carried recipes for unboiled marzipan, with directions for making marzipan holly and fruits, jelly, Christmas pudding, iced mince pies, trifle and shortbread. They also gave instructions for a complete Christmas dinner consisting of ‘clear soup, roast turkey with chestnut and forcemeat stuffing, bread sauce, baked potatoes and Brussels sprouts or celery, Christmas pudding or mince pies’.

The Christmas tree, having been introduced in Victorian times, had by now become firmly rooted (excuse the pun) in the traditional British Christmas. On the outbreak of war wood was one of the first items to suffer supply restrictions, but a spokesman for the state forests let it be known that there would be no shortage of Christmas trees that year.

Henry Bailey wrote: ‘The curtains were drawn and the fairy lamps at the top of the Christmas tree were the only lights. Their red, blue, yellow and green hues shone out and glistened on the tinsel and the silver bells, and it looked very nice in the dark.’ By now strings of coloured electric lights were available, though many people still used candles. Maureen Salmon wrote: ‘Our nursery looked lovely with trails of ivy and holly and with lighted Chinese lanterns.’

A few of the products that were available in late 1939 would soon disappear altogether. For example, some companies were still advertising indoor fireworks that year. Ernie Prowse recalled:

HOW TO MAKE THE PERFECT CHRISTMAS CAKE

10oz butter

12oz Barbados sugar

6 eggs

13oz plain flour

1 teaspoon Borwick’s baking powder

1 teaspoon mixed spice

1 tablespoon black treacle

2oz ground almonds

4oz chopped almonds

1¾ currants

14oz sultanas

10oz mixed peel

grated rind and juice of ½ lemon and ½ orange

wineglassful rum or brandy (optional)

Cream the butter and sugar together. Mix in the eggs and treacle very thoroughly. Add the sifted dry ingredients, the fruit, almonds, lemon and orange juice and rind. Also brandy. Put the mixture into a well greased and lined tin, and bake in a cool oven for six hours (temp 275°), lessen oven heat after two hours. Keep two or three weeks, then cover with almond paste about half an inch thick and ice with royal icing.

For the almond paste mix 3oz each of castor sugar and ground almonds together. Add half a teaspoonful of almond essence and sufficient egg to make fairly soft consistency. Work till smooth and roll out. Cover over cake.

For the royal icing, beat the whites of two eggs lightly and add two teaspoons lemon juice. Gradually beat in 1lb icing sugar till mixture keeps its shape when dropped from spoon. Use immediately, keeping well covered with a damp cloth when in the basin to prevent hardening. Spread over cake with a long knife dipped in cold water. Decorate to suit.

Borwick’s Baking Powder advertisement

Auntie Win always had a lot of Christmas fireworks which must have cost a lot of money. One in particular stays with me; it was a round black thing about two inches high with a touch paper. When you lit it, it would start off with smoke coming out, then it would suddenly send out a long black snake-like thing which would go on for a long time. In the end it would be about three feet long. The only problem was it would give off a lot of smoke and really stink!

Although many people still used candles on trees – indeed in some areas there was no mains electricity – electric tree sets were available, as this advert from the pre-war ‘Slonetric’ catalogue shows.

Paul Fincham recalled:

There was still a good deal of pre-war sort of stuff around. I’d been sent to stay with friends of my parents in Norfolk from September until just before Christmas. I well remember going to do my Christmas shopping at Woolworth’s in Diss before going home to my parents, and you could buy almost anything that you’d have bought in peacetime. I bought, for 6d, a box of those tiny crackers to put on a Christmas tree, and a packet of paper napkins, also 6d, and similar things.

Indoor fireworks were one of the party treats available that year, but like much else, they were soon to disappear.

An advertising campaign encouraged people to buy French food and drink, Alsatian wines, kirsch, cognac, cheeses and the like. One of the more bizarre aspects of that first wartime Christmas was that so many of the troops with the British Expeditionary Force in France, especially the officers, received parcels from home packed with the sort of French produce they themselves could buy in the local shops.

Woman’s Own had its own suggestions:

There’s a lot we can do to cheer the troops … For instance, here’s an idea for mothers and sweethearts and wives who’ve already heaped the usual home comforts on their particular bit of the Forces. You know it’s far more difficult for the authorities to keep the boys from getting bored in their time off than it is to supply food and clothing. So Woman’s Own has arranged for the two main male hobbies – reading and darts – to be carried on even in the most obscure trench in the lines.

Many adverts suggested presents for family members in the forces, and many mothers then, as today, worried that their absent sons might fail to keep clean – as if the Sergeant Major would have allowed that!

We’ll send to any address you like to give a parcel containing super Christmas numbers of five men’s magazines, a set of darts in a case and a charming little Christmas card bearing your name – all for 3s 6d.

Woman’s Pictorial suggested various presents for servicemen:

Of course, you can do other things but knit for your man. Send him his favourite boiled sweets, or jam, biscuits, chutney, plum cake, either that you have made him or bought for him. … You know there will be times when he is billeted in a village or in reach of a village, and of course you want him to do you credit among your French neighbours. He can’t look spruce without shaving cream, spare razor blades, and toilet soap (large tablets and not highly scented or he’ll be called a cissy).

Even if he went off with your photo in his pocket, send him a new one just to show you haven’t changed. Send it in a wallet where he can keep his paper money, and it’s a good idea to line the wallet with jaconet as this is gas-resisting. He’d love snaps of the kiddies, the dog, the house under snow and the first chrysanthemums in the garden, too. … And now a last idea. On Christmas Day save one of everything from the table. A mince pie, a piece of Christmas Cake, a motto from a cracker (see that it’s a nice one), a ribbon from your dress – and send it to him just to show you were thinking about him and wishing he were with you.

A range of gift suggestions for men in the forces from a Women’s Pictorial article, ‘What shall we give them?’, which reflect the rather quaint view of the war prevalent at the time.

There was some dispute in the government over whether a little extra spending that Christmas would be a good thing; several said it was good for morale, whereas the Chancellor, Sir John Simon, insisted that money should not be ‘wasted’ on presents. Others took the view that spending was patriotic – armchair economists pointed out that the war would be paid for through indirect taxation if every adult smoked two packets of cigarettes and drank half a bottle of whisky a day!

David Langdon’s humorous view of the difficulties of buying gifts for troops. The cold winter meant that a balaclava helmet would be a most welcome gift.

Various ‘economical’ presents were suggested, including this, from Woman’s Own: ‘If you have been able to plant bulbs in time for Christmas – you’ll be able to give some of your friends the loveliest gift on earth.’ Also, ‘Half-crown gifts can look like a guinea if you take a little trouble with them. For instance, a gay sixpenny posy makes a two-shilling puff look really elegant – while two quarter-yard lengths of cleverly contrasting georgette [sewn back-to-back] make a very chic and exclusive-looking scarf.’

According to the Guider magazine:

This year we must have an economy Christmas, but we do not want to lose the festive spirit and many Guides will be planning Christmas presents in spite of the war. Not only are there families and friends to plan for, but this year there are many evacuated children who appreciate presents from Guides. Here are some suggestions for making presents out of old pieces of material as well as new for grown-ups and children.

The article went on to give instructions for creating ‘soft toys’: ‘Guides who have had experience making felt toys can start to collect pieces of old grey flannel for elephants, old tweed coats for horses, old felt or velour hats for rabbits, and set to work with the aid of Craft Council patterns to make something out of nothing.’ A selection of patterns cost 1s, while packets containing everything necessary to make the toy cost from 1s 2d to 2s 6d. These included Paul the Polar Bear, Hengist the Horse and Dackie the Dachshund. (It is interesting that the irrational hatred shown by the public towards German dogs during the First World War hardly existed now.) Better still were:

Rubber Toys. Floating toys, in the shape of fishes, seahorses and other aquatic creatures, for the bath, can be made out of old inner tubes of tyres or hot water bottles (the latter should be used for small toys only). They are cut out with scissors and stuck together with rubber solution – the same sort which is used to mend bicycle tyres. They are stuffed with kapok or chopped up bits of rubber or cork sawdust from fruit packing.

Patterns available included Polly the Plaice, Charles the Crocodile, and Monty the Mackerel, price 1d each.

The Guider magazine also had other ideas: ‘For grown-ups: Gas Mask Cases. A gas mask is not a very Christmassy object, but it can be far more cheerful if it is in a pretty case. One made from a Craft Council packet – either a plain cover for the standard box, or a decorated felt sack with a zip fastener – would make a sensible Christmas present which is quite easy to make.’ The pattern for the standard case cost 1d, the packet 7d, while the packet for the felt sack with zip cost 1s 9d.

For those who could afford it, popular gifts for children included uniforms: nurse, Red Cross, pilot officer, and naval officer at 5s 11d each, while for older children a tin helmet was most welcome. Other toys included the traditional boy’s favourite – a fort. Most popular were modern variations: small versions of the Maginot line with underground quarters and pill-boxes and a large turret with a revolving cupola containing a field gun. John Bird remembers ‘looking in toy-shop windows and wondering how I could raise the cash for a model barrage balloon complete with winch and cables, costing about eight shillings. Unfortunately Father Christmas never heard my plea!’

There were also many topical games available, including card games such as ‘Blackout’, or ‘Vacuation’, and numerous children’s annuals were produced. ‘Give books this Christmas and forget the war’, exhorted the Guider. Brian Martin recalled:

I was 8 years old when war broke out and I had just started to have a Meccano set as the main present, a set being added each year to convert No. 1 into No. 2, etc. War stopped this so I was given a balsa-wood flying scale model kit to make up, cutting spars, stringers and moulding propellers. The kits were by Astral. In 1942 the Stirling giant bomber with 38-inch wingspan cost 21s. At these prices you can see why this would have to be the main present. Over the years I had a Stirling, Bristol Blenheim, Hampden, Whitley and Lysander.