Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

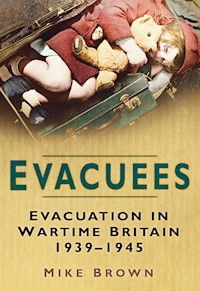

As the last days of peace ebbed away in 1939 and the outbreak of the Second World War appeared inevitable, a massive exodus took place in Britain: nearly two million civilians, most of them children, were taken from the cities, industrial towns and ports to the relative safety of the British countryside. For many of these bewildered children this was the first time away from their families or even their own home town. But for overseas British nationals evacuacted to the mother country from the Channel Islands and Gibraltar, the shock of the upheaval was great indeed. Carrying pitifully few belongings, they had no idea where they were being sent - for many it was the beginning of a great adventure, for some a nightmare. Mike Brown combines factual narrative with contemporary eyewitness accounts and oral history extracts to investigate the phenomenon of evacuation in Britain during the Second World War. Illustrated with a variety of contemporary photographs and ephemera, Evacuees provides a fascinating, amusing and sometimes disturbing glimpse of how children and adults coped with the trials and tribulations of evacuation. It will appeal to anyone who is interested in reading about life on the Home Front during the Second World War, and especially to anyone who was an evacuee.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 211

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2005

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

EVACUEES

EVACUATION INWARTIME BRITAIN1939–1945

MIKE BROWN

First published in 2000

Reprinted in 2010 by

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© Mike Brown, 2010, 2013

The right of Mike Brown to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 9572 9

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

Acknowledgements

Introduction: ‘Bloody Vackees!’

1

How It All Began

2

Planning and Rehearsal

3

The First Evacuation

4

‘Leave Them Where They Are, Mother’

5

The Second ‘Great Trek’

6

The Third ‘Great Trek’

7

Arrival and Billeting

8

Billet Life

9

Homecoming and After

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

I would like to take this opportunity to thank the following people who so kindly shared their memories with me:

Audrey Wines née Arnold, Evelyn Fisher née Baker, Shirley Symons née Barry, Vera Biddle, Arnold Beardwell, Jane Black, Pamela Nicolle née Buckley, Christine Castro née Pilgrim, Mrs R. Channing, Lavender Baskett née Clarke, Lillian Clegg, June Wolfson née Cohen, Betty LeBail née Collas, Jennings née Cordell, Kathleen Corton, Rita Kirk née Curtis, Philip D’Arthreau, Kenneth Dobson, Jennifer D’Eath, Tom Dewar, Bryan Farmer, Joyce West née Fry, Betty Sutton née Gagg, Jean Barber née Garnham, Rozel Garnier, Iris Knudsen née Gent, Frances Lloyd née Hardy, Edward Harrington, Ann Headley née Peppercorn, Enid Helyer, Doreen Ramsenius née Hooper, Ann Beardwell née Honey, Betty Hull, Walter Hurst, Nita Luce née Jenkins, Betty Judge née Jones, Roy Judge, Mavis Burren née Kerr, John Kirk, Doreen Last, Iris Tilman née McCartney, Miriam McLeod, Brian Martin, Peggy Mayhew née Masterson, Alice Bott née Morgan, Ursula Nott, Mary Facey née Noyle, L. Powis, George Powis, Christine Jones née Pring, Roy Proctor, Ernie Prowse, Iris Prowse née Miller, Henry J. Ramagge, Joan Letts née Rands, Betty Easter née Robinson, Eddie Roland, Clarice Ruaux, Doug Ryall, Archie Salvidge, Eric Sephton, Mrs Sewell, Vera Sibley, E.A. Roy Simon, Mary Kingham née Spink, Linda Toomey (ex-Stebbing), Joan Stone née Stephenson, Joyce Stockton, Margaret Thompson, Margaret Durham née Watling, W.J. Wheatley, Caroline Williams, Joyce Withers, David Wood, Donald Wood, Margaret Woodrow, Mrs M. Worner née Phizacklea, Mr S.A. Yates.

I am grateful to Andy Mathieson for the use of Stillness School log, and Margaret Baker for kindly allowing me to use excerpts from her father, Fred Bond’s unpublished memoirs.

My thanks also go to the following who allowed me to use illustrations:

Joyce Fry, Roy Judge, Iris Miller, Doug Ryall, Phyllis Sewell, June Wolfson, Margaret Woodrow, Donald Woods, Margaret Thompson, Joseph Morello, Bromley Local Studies Library, Hull Central Library, Kent Messenger Group Newspapers, London Metropolitan Archives, Southwark Local History Unit.

INTRODUCTION

‘Bloody Vackees’

During the final days of peace in 1939 a massive exodus took place throughout the country. Nearly two million civilians, most of them children, were taken from the cities, industrial towns, and ports of Britain to the relative safety of the countryside, using trains, buses, trams, coaches, and even pleasure steamers. For many of the children it was the first time away from their families, for some the first time outside their town. They went, carrying a few belongings, not knowing where they would end up – when a group waiting at a London station were asked where they were going, one child replied, ‘We don’t know, sir, but the King knows.’ For some it was the beginning of a great adventure, for others a nightmare. This was the first great evacuation, but not the last. During the course of the war there were to be two more and, in between, a constant flow of individuals and groups both into and out of danger.

This mass evacuation was the result of planning going back to the early 1920s; progress was sometimes painfully slow, sometimes almost in a panic, depending on the mood of the international situation. It has often been repeated that the evacuation programme went off with no hitches, but this is more what was reflected by the widespread propaganda at the time, aimed at reassuring those parents who had sent their children and encouraging those who had not. But there is no doubt that evacuation saved thousands of lives; up to the end of 1942, only twenty-seven children evacuated from London were killed in air raids, a tiny proportion compared with casualties among those who remained, the majority of whom were not physically hurt but many of whom suffered for years from the psychological effects of the bombing.

A large number of the evacuees were from the slums and tenements of the inner cities; some of the householders who took them in were given an insight into a world of poverty which many assumed had disappeared with Queen Victoria. The outcry that followed led to the Beveridge Report and today’s welfare state. On the other hand, many of the evacuees were given an insight into the world outside the cities, of farms, countryside, and animal husbandry, which encouraged some to stay there after the war, and left many with a life-long love of the countryside.

The mass evacuation of the inner cities was an exercise which changed a generation, if not the whole country. Using contemporary documents, and the words of those who experienced it, I have tried to trace the story of the evacuation, the planning, the first attempt at the time of the Munich Crisis, and then the real thing. Then came the phoney war and the drift home, which soon became a flood, but for many their evacuation was a more permanent affair and many were to experience both the problems and the joys of billet life before they could finally return home.

Boys from Rochester Mathematical School starting their own ‘Great Trek’. Notice the gas masks, especially the cloth case on the left, and the evacuation label. (Kent Messenger Newspaper Group)

ONE

How It All Began

As with so many aspects of the Second World War, the roots of evacuation can be traced back to the First World War. The first air raids on Britain began as early as 1914, with London being bombed for the first time in May of the following year. During the course of that war, fourteen hundred civilians were killed in just over one hundred raids, first by Zeppelins, then by heavy bombers. The citizens of Britain, generally secure from enemy action for almost a thousand years, now found themselves vulnerable, and became more so with each advance in aviation technology, in an inter-war period marked by record-breaking long-distance flights by such people as Charles Lindbergh, Amy Johnson and Amelia Earhart, and air races, such as the Schneider Trophy.

Less than three years after the signing of the Versailles Treaty the Air Raid Precautions, or ARP Committee was set up to examine the problems posed by air raids. Included in the topics for discussion suggested by the chairman, Sir John Anderson, at its first meeting in May 1924 was the possible evacuation of sections of the civilian population. The committee’s earliest investigations into ‘evasion’, or evacuation as it came to be known, hinged on the premise that London, as the capital, would be the principle target of air attacks. The ARP Committee’s first report in December 1925 established two basic points:

1)that it would be impossible to relocate most of the activities normally carried out in London, and

2)that the nation could not continue to exist if bombing forced these activities to cease.

The committee pointed out the disastrous effect that heavy civilian losses could have on the country’s morale, and that in a democracy, curbs on the movement of private citizens could not be too widesweeping. It therefore proceeded to separate the population into two groups; those involved in vital work, and those whom they described as les bouches inutiles, i.e., those who played no direct part in essential war work especially women, children, the aged, and infirm. This group should be encouraged and helped to move. The committee realised that this would require a great deal of planning, and it was therefore proposed that schemes be drawn up by the Ministries of Health and Transport and the Boards of Education and Trade. The schemes needed to concentrate on the poorer districts of the capital, as wealthier families would be able to arrange to evacuate themselves. Some committee members were also of the opinion that the ‘foreign, Jewish and poor elements’ who lived in the poorer areas would be likely to panic once bombing started, and should be evacuated as soon as possible to prevent them undermining morale. If this was not enough, they also believed that after bombing the poor would ‘flock’ to the wealthier areas and loot them wholesale. The Office of Works, it was suggested, should be instructed to make plans for the removal of artworks, national treasures, and historic and vital records to places of safety – safe, not only from bombing, but also, presumably, from being looted by the poor! This early work established basic principles upon which all later schemes were founded, the most important conclusions being that evacuation was desirable, that it should apply to specific groups, and that it should be voluntary.

By 1930, the main plan for civilian evacuation still presumed that the centre of London was effectively the only danger area. In this scheme, the London Underground would be the main vehicle for transporting thousands of Londoners to the outskirts of London and, it was assumed, safety. There were no plans as to what these ‘evacuees’ would do once they got there.

In 1931 another committee was set up, under the chairmanship of Sir Warren Fisher, to look into ARP services. Committee members were told by their experts that, in a future war, 600 tons of bombs per day could be dropped on Britain, following a huge opening assault dropping 3,500 tons in the first 24 hours causing 60,000 dead and 120,000 wounded on the first day, followed by 66,000 dead and 130,000 wounded per week thereafter. These figures led them, inevitably, to the conclusion that evacuation would play a vitally important role in any defence scheme, and they began close examination of the problem of evacuating 3½ million citizens from various parts of London. However, the findings of this committee, reported in 1934, were somewhat overshadowed when the scope of the ARP was enlarged to include not just London but the country as a whole in 1934/5. This latter move culminated in the formation of the ARP Department of the Home Office.

Life, and death, in the city: a children’s hospital ward in Belfast the morning after a raid. (HMSO)

The idea of evacuation was certainly not unique to Britain, and other countries were pushing ahead with their plans; the French Government, for instance, issued a handbook on evacuation in 1936 setting out their scheme. All non-vital civilians would be encouraged to leave the towns; those closely related to people who needed to stay behind would be evacuated to places nearby, while those who had to remain would be evacuated each night. The mayor of each town would be responsible for the evacuation of his town, and for liaison with surrounding villages as to billeting. People were to be evacuated by trains, trams and buses, and all villages and towns were expected to accept a number of evacuees equal to their population.

French evacuation: Parisian children undergoing medical inspection on arrival at their new billets, September 1939.

For the next few years evacuation plans progressed slowly in Britain. Some work was done on a London evacuation scheme but the 1937 government booklet The Householder’s Handbook, updated in 1938, gave only one suggestion as to what to do if war threatened: ‘If you live in a large town, children, invalids, elderly members of the household, and pets, should be sent to relatives or friends in the country, if this is possible.’ As with other civil defence measures, the onus was placed on individuals to make their own arrangements.

In spite of optimistic statements by the Home Secretary, Sir Samuel Hoare, government plans for large-scale evacuation were still in a very rudimentary state by early 1938. In the Home Office air raid scheme issued to the county boroughs in March of that year, the paragraph on evacuation read: ‘To be completed as and when further directions are given by the Secretary of State.’ An accompanying circular instructed local authorities to take no action until specific instructions had been received from the Home Office.

On 26 May 1938 the Home Secretary announced that he had set up the ‘Committee on Evacuation’, made up of four MPs under Sir John Anderson. They met for the first time on the following day, when they agreed to look at foreign schemes. Meanwhile, it was widely accepted that the evacuation of children should form the most important part of any scheme, and would also be the easiest to organise. J.B.S. Haldane, in ARP, noted that: ‘There is one class of the community which could be evacuated at very short notice, and with very little difficulty. These are the school children, and particularly the elementary school children. They are accustomed to obey their teachers, at least up to a point.’ One of the many proposals put to the Anderson Committee was for the erection of 600 camp schools in rural areas, each to house 500 children, with foundations laid for other huts (stored in sections) so that the population of each camp could be increased to 5,000 in the event of an emergency. Each camp would be allocated to ten elementary schools that, in peace time, would use the camp in rotation, for one month each. In the event of war all ten schools could be evacuated to the camp, with the advantage that they would already know the camp and the surrounding area.

By this time, the government was under continued pressure to come up with definite plans. When questioned in Parliament about evacuation on 1 June 1938, the Home Secretary, was still vague: ‘That question raises so many issues that although we have plans prepared in outline, I should be very loath to decide upon any one of them until I felt that there was general body of public opinion outside behind it.’ The Anderson Committee reported back to the Home Secretary before the end of July, concluding that: ‘The whole issue of any future war may well turn on the manner in which the problem of evacuation from densely populated industrial areas is handled.’ While agreeing with the findings of earlier committees, the Anderson Committee further proposed that arrangements for the reception of refugees should rest primarily on accommodation in private houses under compulsory billeting powers, with the initial cost being borne by the government, though ‘refugees’ able to do so should later be required to make some contribution. Detailed plans should be laid to evacuate schoolchildren, with the consent of their parents, school by school, in the charge of their teachers and at government expense. Such a scheme, concluded the committee, could be organised within a few months, and it pressed for central and local organisations to be set up to carry out the required planning, beginning with the education of the public on the necessity for the scheme.

Here, then, for the first time, the committee had started to address the two problems that earlier schemes had failed to do: 1) what to do with the evacuees once they were out of the cities; and 2) in a voluntary system, how to encourage people to leave. Many saw these, correctly, as it turned out, as the greatest problems for any plan – they would never be completely solved. J.B.S. Haldane argued from his experiences in Spain that: ‘People are only willing to leave their homes after so much bombing that transport is partially paralysed, and they are only willing to give full hospitality as honoured guests to their starving and lousy fellow-countrymen after they have learned patriotism.’

On 18 June 1938 the Women’s Voluntary Service (WVS) was formed, primarily for recruiting women to the Civil Defence Services. However, from the very first the WVS proved adept at turning its hand to any necessary task and in July its founder, Lady Reading, addressed a secret meeting at the Girl Guides’ Headquarters where she asked for the names of Guiders prepared to take responsibility for local evacuation arrangements, backed up by the WVS. Next, the support of the Women’s Institutes (WI) was secured, and a WVS Evacuation Committee was set up that included representatives of the WI and the Guides. They then appointed a County Evacuation Officer in every county likely to receive evacuees.

Early in September 1938, with the Munich Crisis brewing, the Committee for Imperial Defence accepted the Anderson Committee’s proposals.

TWO

Planning and Rehearsal

In September 1938 Britain found itself on the brink of war. Germany laid claim to a part of Czechoslovakia, the Sudetenland, which lay along their joint border; the Czechs dismissed their claim. Both countries prepared for a war into which France and Britain would be drawn by treaty commitments. Defence measures were rushed forward. On the basis of the Anderson Committee report, a scheme, later to become known as Plan 1, was hastily patched together for the evacuation of London children. On 22 September a special conference was held at Chelmsford, where Essex towns were asked to take their share of the 2 million people expected to be evacuated from the capital. This included almost 45,000 to be transferred to the Colchester area, to arrive over a five day period at a rate of nine train loads per day. Four days later, the Government asked the WVS to help every local authority in the reception areas to carry out a house-to-house census of accommodation likely to be available for evacuees (in some places this job was carried out by the Women’s Institutes). The survey found almost 5 million spare billets in the reception areas, in most of which the WVS set up an evacuation committee, working with the Local Authority’s Chief Billeting Officer, to coordinate the work of reception and billeting.

A letter dated 27 September 1938, setting out the items that the boys of Brockley Central School, South London, should bring with them for evacuation. Notable among the items of food are two boiled eggs and (presumably to counter their effect) twelve prunes.

At the height of the crisis on Thursday 29th the Government published its plans for the assisted evacuation of 2 million people from London, one quarter of them schoolchildren. Already many were moving themselves and their families away from the main cities, the railways reporting passenger numbers of Bank Holiday proportions, with Wales and the West Country as favourite destinations. The Government’s plans were to commence the following day, the 30th, with the evacuation of half a million London schoolchildren. In Europe, however, the Munich Agreement, handing over the Sudetenland to Hitler, was signed that day, and the evacuation scheme was called off at the last minute, much to everyone’s relief, for the scheme was nothing if not rudimentary. But 4,000 children from nursery and special schools had already been evacuated by ambulances to schools and camps in the countryside – they were all back home by 6 October, but the experience gained proved indispensable for later plans.

A Great Western Railway evacuation train schedule. It all seems very well organised, but in reality schools on their arrival at stations were put on the first train available, which was often not the train on which they were due to travel.

Caroline Williams was at teacher training college in London at this time:

In September I returned to St Gabriel’s College in Camberwell. Immediately we were overwhelmed by the Munich Crisis and our principal decided to send us home but asked if any of us would volunteer to act as escorts to a nursery school in the Mile End Road, before we finally went home. With two other students I started off from the Nursery in a coach with the Nursery staff, and the children, plus potties – destination unknown.

We eventually arrived in Aylesbury, Bucks. It must have been on the green of a housing estate where we were finally unloaded from the coach. The local mothers stood around and began to choose the children, ‘I’ll have that one’, ‘I’ll have that one’, I heard as we stood looking on. A woman asked us, ‘Are you teachers?’ We told her we were students and would be travelling to our homes the next morning and she hastened to offer to put us up for the night, probably relieved at the outcome.’

W.G. Eady, Deputy Under Secretary of State at the Home Office, later said that the scheme would ‘just about have stood up to the requirements of getting refugees out of London and bedding them down that night while we tried to sort out what was going to happen afterwards.’

A post-mortem of the experiences of this time resulted in the responsibility for evacuation shifting in November 1938 from the Home Office to the Ministry of Health, and the Department of Health for Scotland. The recommendations of the Anderson Committee were published and led to strong pressure on the government to accept them in full. This was done, and the lessons learnt during the Munich Crisis were also incorporated – from now on the arrangement of sufficient billets in advance became a vital part of the scheme.

A new scheme was drawn up by the Ministry assisted by officers seconded by the Board of Education. This scheme divided all parts of the country into three classes: evacuation, reception and neutral areas. The evacuation areas were those from which ‘priority’ groups were to be given the opportunity to transfer to safer areas in the event of an emergency; reception areas were those places that would receive them; and neutral areas, as their name implied, were neither one nor the other.

A government leaflet, Evacuation – Why and How?, issued to all households in July 1939, setting out the details of the government’s evacuation scheme.

Evacuation was to apply to four main groups:

1)Nearly 4,000,000 children, mothers and invalids living in cities whom the government had arranged to remove, if they wished, to safer areas.

2)Individuals who chose to leave under their own arrangements – this was known as private evacuation.

3)Business firms and private companies, known as business evacuation.

4)The government, ministers, MPs and civil servants. The Ministry of Health was to be in overall charge of the scheme, while the coordination of the Ministry’s scheme was the responsibility of local education departments.

In July 1939 the Lord Privy Seal’s Office issued a series of leaflets on Civil Defence which were delivered to every house in the country. The third of these, entitled Evacuation – Why and How?, contained the following list of the evacuation areas under the government scheme:

An evacuation poster. Once it was decided that evacuation would be voluntary, it was necessary to convince the public to cooperate. One common tactic was to appeal to mothers.

a) London, as well as the County Boroughs of West Ham and East Ham; the Boroughs of Walthamstow, Leyton, Ilford and Barking in Essex; the Boroughs of Tottenham, Hornsey, Willesden, Acton, and Edmonton in Middlesex; b) The Medway towns of Chatham, Gillingham and Rochester; c) Portsmouth, Gosport and Southampton; d) Birmingham and Smethwick; e) Liverpool, Bootle, Birkenhead and Wallasey; f) Manchester and Salford; g) Sheffield, Leeds, Bradford and Hull; h) Newcastle and Gateshead; i) Edinburgh, Rosyth, Glasgow, Clydebank and Dundee.

The choice of evacuation areas caused many protests. For example, Croydon was originally designated a neutral area. A deputation visited the Ministry, pointing out its vulnerable position, and in July the Ministry accepted Croydon’s arguments and it was redesignated. Plymouth, on the other hand, was subject to several heavy raids yet, despite many official requests, the Ministry refused to make it an evacuation area until after the heaviest raids in March and April 1941. H.P. Twyford in his book about Plymouth during the war, It Came to Our Door, commented: ‘I do not think Plymouth ever quite forgot or forgave that disregard of their appeal to send the children away.’ There was, of course, a fair amount of private evacuations made, but many parents, especially the poorer ones, were unable to arrange or afford to do so.