5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: New Island

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

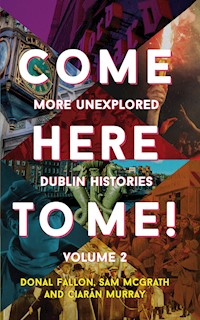

Donal, Sam and Ciarán from the hugely popular blog Come Here To Me! are back with a brand-new collection of fascinating, surprising, and little-known tales from the hidden history of Dublin, Ireland's often weird and always wonderful capital city. In a history book that looks at things from a different angle, Come Here To Me! Vol. 2 celebrates an unexplored Dublin: its public duels and street gangs, suffragettes and drag queens, as well as its not-so-secret gay bars and failed vegetarian societies. It looks at the people the city has chosen to remember and the places it has decided to forget (or worse, allowed to be turned into a Starbucks). With fresh, new perspectives on the lives and histories of the city, Come Here To Me! Vol. 2 is a history book like no other . . .

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

COME HERE TO ME!

Vol. 2

COME HERE TO ME!

Vol. 2

More Unexplored Dublin Histories

Donal Fallon

Sam McGrath

Ciarán Murray

COME HERE TO ME! VOL. 2

First published in 2017 by

New Island Books

16 Priory Hall Office Park

Stillorgan

County Dublin

Republic of Ireland

www.newisland.ie

Copyright © Donal Fallon, Sam McGrath, Ciarán Murray, 2017

The Authors assert their moral rights in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright and Related Rights Act, 2000.

Print ISBN: 978-1-84840-633-9

Epub ISBN: 978-1-84840-634-6

Mobi ISBN: 978-1-84840-635-3

All rights reserved. The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Except as may be permitted by law, no part of the material may be reproduced (including by storage in a retrieval system) or transmitted in any form or by any means; adapted; rented or lent without the written permission of the copyright owner.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

New Island Books is a member of Publishing Ireland.

Contents

Dedications and Thanks

A Divided Rathmines

Drunken Vagabonds and Lawless Desperadoes

A Forgotten Tragedy on Hammond Lane, 1878

From Grandeur to Ruin: the Story of Sarah Curran’s Home in Rathfarnham

Admiral William ‘Guillermo’ Brown

A Planned Massacre on Grafton Street, June 1921

Doran’s of Castlewood Avenue

Dublin’s First Gay-Friendly Bars

A Spectre is Haunting Ballyfermot: the 1952 Co-op Scandal

A Dublin Reimagined

Interview with Paul Cleary of The Blades

‘Fortress Fownes’ and the Story of the Hirschfeld Centre

Daniel O’Connell’s Last Duel

The Four Corners of Hell: a Junction with Four Pubs in the Liberties

John ‘Spike’ McCormack

De Valera and the ‘Indian Priest’

Feuding Unions and Mills’ Bombs

Arthur Horner: the Welsh Refusenik of the Irish Citizen Army

Before Monto, There Was Grafton Street

Max Levitas: Jewish Dubliner and Working-Class Hero

The Christmas Monster ‘Kohoutek’ and the Children of God

The Rabble and the Custom House

Remembering Paweł Edmund Strzelecki

18 Aungier Street: from Neighbourhood Local to Cocktail Bar

The Proclamation and William Henry West

Antonin Artaud, the Staff of Saint Patrick, and a Trip to Mountjoy Prison

Before Panti, There Was Mr Pussy

Historic Dublin Pub the White Horse is Now a Starbucks

‘Severity for Suffragettes’, Dublin 1912

Konrad Peterson: Latvian Revolutionary and Pioneering Civil Engineer

The Shooting of Thomas Farrelly in the Markets

Bull-Baiting in Eighteenth-Century Dublin

From McDaid’s to the Summer of Love: the Mysterious Emmett Grogan

Edward Smyth’s Moving Heads

Lesser-Known Dublin Jewish Radicals

Herbert Simms and the 1930s War on Slumdom

Who or What Is a ‘Jackeen’?

The Gunrunner in the Four Courts

Connolly and Dublin Anarchists

The Bolsheveki Bookies

Bona Fides, Kips, and Early Houses

Leaving Her Mark on Kildare Street: the Work of Gabriel Hayes

The Crimean Banquet, 22 October 1856

Oscar Wilde, Speranza and the Young Irelanders

Tommy Wood, the Youngest Irish Spanish Civil War Fatality

Stalin’s Star: the Unwelcome Orson Welles

The Former Life of a Talbot Street Internet Café

Dublin’s First Vegetarian Restaurants

Dublin’s Historic Breweries: Watkins’ of Ardee Street

The ‘Denizens of the Slums’ Who Looted Dublin

The Pagan O’Leary and John’s Lane Church

Number 10 Mill Street, Blackpitts

You’ll Never Walk Alone: Heffo’s Army and the Question of What to Do With Them

The Humours of Donnybrook

Keep Rovers at Milltown

Select Bibliography

Donal Fallon

To Leagues O’Toole. The pleasure, the privilege is mine.

I have had the good fortune to work with many people in this city who are passionate about history.

Trevor and the entire team at the Little Museum of Dublin have been great supporters of this blog and project, and great champions of Dublin history in their own way. I would also like to thank all in Dublin City Council, in particular all in Dublin City Public Libraries, who have provided me with many opportunities to engage with Dubliners about the past.

I am grateful to all those who have provided me and the blog more generally with a platform over the years. My thanks to Rabble, Lois and Sam at Dublin Inquirer, all at Newstalk Drive and RTÉ’s The History Show and the inimitable Tommy Graham of History Ireland. I am also grateful to all at the UCD Access and Lifelong Learning Programme team, who have allowed me to teach over many years.

I am grateful to the community of writers and fellow historians who I call friends. In particular, I thank the historians Brian Hanley and Pádraig Óg Ó Ruairc.

My thanks to everyone who has given their time to our ‘Dublin Songs and Stories’ nights in the Sugar Club, in particular the great Brian Kerr who captivated the room and who embodies all that is great about this city. There are too many people to name individually, but my thanks to all artists, musicians and others who have supported the nights.

Lastly, I am beyond indebted to friends and family who kept faith through an incredibly turbulent period of depression and difficulty. All things pass. Gabhaim buíochas libh go léir.

Ciarán Murray

To those who continue to support the blog almost eight years since its inception.Keep the Faith.

Thanks to:

Dan and all at New Island for giving us the opportunity to bring more of Dublin’s stories to light. To the Gutter Bookshop, the Winding Stair, Books Upstairs, Designist and Hodges Figgis and the many stores who keep plugging us, six years on from our first book.

To Johnny Moy and the Sugar Club, and all those who have spoken, played at or attended our Songs and Stories events. These singers, songwriters, poets, playwrights, authors, artists and activists are the personification of what we strive to be as a blog. Thanks for the great nights and spectacular moments.

Those who have provided the inspiration for or assistance with articles in this book, not least Frank Hopkins, Harry Warren, Noel Redican, Aileen O’Carroll and Cormac O’Malley. In particular I’d like to thank Jelena Djureinovic for helping me cross the finish line.

My friends and the extended Murray clan. Ma, as always and forever in my thoughts, Da.

Last but not least, the other two authors of this book.

Sam McGrath

To my one and only Ciara Ryan. For turning a black-and-white world into colour.

Since our first book was published five years ago, I’ve had the privilege to work with many brilliant archivists and historians. I’d like to take this opportunity to thank the following people: Tony at the Archive of the Irish in Britain, all at the National Library of Ireland and the National Archives of Ireland; Becky and Chris of U2’s archive; Gordon and Lucinda of the Joe Strummer archive, and Dick and Hughie of The Atrix. Also to Brian, Paul and Ger of Eneclann; Mark at Arcline; Martin Bradley and finally to Cécile, Niamh, Michael and Rob and all at the Military Service (1916-23) Pensions Project and Military Archives.

Community history groups dotted around the city continue to inspire us and make history accessible for all. Special shout-out to Joe (East Wall), Ado and Cieran (Cabra), Fin, Stew, and Alan (Smithfield and Stoneybatter) and the Gernika80: then and now project. Also my gratitude to Brian and all at Saothar.

Thanks to a number of people who provided additional comments and information for pieces originally published online. ‘The White Horse’ article – Eanna Brophy, Hugh McFadden, Dunster, Freda Hughes, Fearghal Whelan, Niall McGuirk, Alan MacSimon, Des Derwin, Stompin’ George, and Shay Ryan. ‘Rice’s and Bartley Dunne’ article – Tony O’Connell, Mark ‘Irish Pluto’, Mark Jenkins and John Geraghty. ‘Four Corners of Hell’ article – John Fisher, Seán Carabin and Brendan Martin. ‘Max Levitas’ article – Manus and Luke O’Riordan and Rob and Ruth Levitas.

Lastly, I’d like to convey my deepest gratitude to my parents Billy and Carolyn, my family and all my friends for all their encouragement and guidance.

A Divided Rathmines

Sam McGrath

For more than seven decades, only a couple of streets in Dublin 6 separated the affluent Georgian homes of Mount Pleasant Square and the poverty-stricken slum of Mount Pleasant Buildings.

Architect Susan Roundtree wrote in her 2006 article ‘The Georgian Squares of Dublin: an Architectural History’ that Mount Pleasant Square has ‘justifiably been described as one of the most beautiful early nineteenth-century squares in Dublin’.

Developed in the early nineteenth century by English speculative developer Terence Dolan and his sons, the square comprises of 56 terraced houses overlooking a small public park and Mount Pleasant Lawn Tennis Club, which dates back to 1893.

The 1911 census shows that 387 people lived on the square that year, including 149 Catholics and 214 Protestants. A sample included a wine merchant (at no. 10), a landlord (no. 18), an electrical engineer (no. 22), and a secondary-school teacher (no. 40). These middle-class residents enjoyed access to squash, badminton, and tennis courts, as well as a private garden on their doorstep.

It was a different world altogether in Mount Pleasant Buildings, just a stone’s throw away. The block of ten large flats, situated in a small area on the hill between Ranelagh and Rathmines, later became a by-word for poverty and bad planning.

Rathmines Urban District Council started building the blocks in 1901 to provide accommodation for the local working class. The township of Rathmines was incorporated into the City of Dublin in 1930, and its functions were taken over by Dublin Corporation (now Dublin City Council). The blocks were completed in 1931, and contained 246 flats: 60 one-roomed, 150 two-roomed, and 36 three-roomed residences.

Widespread unemployment among residents and a lack of basic sporting and community facilities soon led to anti-social behaviour. The former caretaker of the buildings told Irish Times journalist Maev-Ann Wren, according to a 5 March 1979 article, that ‘things really started to come apart in the late ’40s’. Petty crime and anti-social behaviour increased, and the area began to get a bad name. Large families were moved into very small flats, and overcrowding became a problem. In the same 1979 piece, Wren wrote that:

Poor quality housing will inevitably deteriorate, become low demand, achieve open area status and so a ghetto will be created … If all these inadequate or problem families are placed together it seems inevitable that a problem area will result.

Families who were evicted from other social housing around the city were moved to Mount Pleasant Buildings while they paid off their rent arrears. An RTÉ documentary from the late 1960s, which is available to view online focused on the buildings. It interviewed a young couple who lived with their four young children in one room. Their flat was beside the continuously overflowing communal toilet that was shared by fourteen people. The mother told the interviewer, ‘it’s like punishment for not paying your rent … no decent person should have to live in this condition’.

A frustrated man who lived in a one-room flat with his wife, his brother and his sister-in-law asked the reporter, ‘There’s five thousand on the housing list. Why can’t they house them? They’re building office blocks overnight. What’s more important? Office blocks or human beings? If this is what they call a Roman Catholic country, I’m disgusted.’

Resident Lee Dunne wrote a fictionalised account of growing up in Mount Pleasant Buildings in his book Goodbye to the Hill, which was published in 1965. Banned due to some sexual content, it went on to sell over a million copies. Another famous resident was the Limerick-born film star Constance Smith, who lived there with her family in the 1940s.

Journalist Michael Vinny in the 28 April 1966 edition of the Irish Times described Keogh Square in Inchicore, Corporation Buildings off Foley Street in the north inner city, and Mount Pleasant Buildings as ‘the three Dublin ghettos … used by the corporation as dumping grounds for problem families’.

The Trinity News reported on its 29 January 1970 front page about a group of students who were ‘attacked, terrorised and beaten up by hooligans’ who tried to gate-crash a house party that they were holding in Ranelagh. The students were attacked with bottles, frying pans, belts, and metal bars. Two of their windows were put in. The article noted that the ‘attackers disappeared into the nearby Mount Pleasant Buildings, a corporation house area popularly known as “The Hill” [which] is notorious for gang violence’.

A column titled ‘Living in fear in Ranelagh’ by Eileen O’Brien in the 10 December 1971 edition of The Irish Times was particularly harrowing. She talked to a number of frightened residents, including an old woman who, after coming home from a short stay in hospital, found her flat wrecked. Her clothes, coal, and a statue of the Sacred Heart that had belonged to her father had been taken.

A former resident who had recently moved into new corporation flats in Fenian Street, told the Irish Times, according to its 29 June 1973 edition, that:

[It] was an awful place. We had only a communal toilet and wash-house. You had to go down a passage for water and the windows were getting broke all the time. It was a woeful place to live in, woeful … [It] was not too bad at first. I was there 17 years, and at first they left you alone. Lately there are gangs there … You could not go out.

In the early 1970s, the buildings were ‘deemed unfit for human habitation’, and the first block was demolished in October 1972. By July 1977, only ten families remained – six were squatting.

Only one block was still standing by March 1979. Wren wrote in the Irish Times that:

the community is now scattered. Tenants in condemned blocks receive priority on the corporation waiting list. They are all over the city: in York Street, Holylands, Ballymun, Clondalkin. Many would prefer to be rehoused locally but there is very little corporation housing in the area. Rathmines is one of the few mixed areas in the city, but to a decreasing extent. Property values rise as the more affluent move back into the city and the poorer must move out to new corporation estates and less mixed areas.

The flats were replaced with low-density corporation houses based around the new streets of Swan Grove and Rugby Villas.

Unsurprisingly, the area’s problems did not vanish overnight. Anti-social behaviour still plagued the community, and career criminal Martin Cahill (aka ‘The General’) was one if its more infamous residents in the 1990s. Having lived in the rundown Holyfield Buildings in the 1970s, he had moved to a house at 21 Swan Grove. He was shot dead by the Provisional IRA in August 1994 just around the corner, at the junction of Oxford Road and Charleston Road.

Sandwiched between Ranelagh and Rathmines, this small working-class enclave with a chequered history was a stark example of extreme poverty and extreme wealth attempting to cohabitate.

Drunken Vagabonds and Lawless Desperadoes

Ciarán Murray

Dublin has always had its fair share of troublesome groups, from the Pinking Dindies, the Liberty Boys and the Ormond Boys of the eighteenth century, through the various fracas of the Animal Gangs, on to the Black Catholics in the 1970s and ’80s, and now today’s variant. The notion of gang warfare here isn’t exactly a new one.

Riotous behaviour was a regular occurrence in the eighteenth century, but one event that stands out is a three-day riot involving both the Liberty Boys and the Ormond Boys that brought Dublin to a standstill in May 1790. Accounts of Dublin from the turn of the nineteenth century are rarely without mention of the two groups, both whose notoriety still rings true to this day. Injuries, maimings and deaths are all purported to have taken place in this particular encounter though, making it one of their bloodiest.

According to J.D. Herbert’s Irish Varieties, for the Last Fifty Years: Written from Recollections, the Ormond Boys were the ‘assistants and carriers from slaughter-houses, joined by cattle drivers from Smithfield, stable-boys, helpers, porters, and idle drunken vagabonds in the neighbourhood of Ormond Quay’, whilst the Liberty Boys were:

a set of lawless desperadoes, residing in the opposite side of the town, called the Liberty. Those were of a different breed, being chiefly unfortunate weavers without employment, some were habitual and wilful idlers, slow to labour, but quick at riot and uproar.

The Liberty Boys’ infamy spread further than Dublin. References to them can be found in several newspaper articles from across the water, including one in the Leeds Mercury from January 1867 that referred to them as French Huguenots who had ‘degenerated physically’.

They are the Liberty Boys of Dublin, the dwellers in ‘The Coombe’, or hollow sloping down to the river, famous for their lawlessness, their strikes, and their manufactures of poplin and tabbinet. They do not seem at all favourable specimens of humanity as you watch them leaning out of windows in the tall, gaunt, filthy, tumble-down houses around and beyond St Patrick’s.

The hostility between the two gangs often led to full-scale riots involving upwards of 1,000 men, and these occurred several times a year, but especially in the run-up to the May Day festival. The city would be brought to a standstill, with businesses closing, the watchmen looking on in terror, as battles raged for the possession of the bridges over the Liffey. John Edward Walsh’s Rakes and Ruffians reports the Lord Mayor of Dublin, Alderman Emerson, as saying of the riots: ‘it is as much as my life’s worth to go among them’.

The battle this piece refers to began on Tuesday 11 May 1790 and lasted several days. It coincided with an election in the city, although an opinion piece in the Freeman’s Journal on the Thursday of that week described the violence as wanton, saying:

The situation of the capital on Wednesday night was dreadful in the extreme; it was shocking to civilisation, for outrage was openly and without disguise directed against the civil protection of the city. On other occasions, grievance, from sickness of trade, from injury by exportation of foreign commodities, from the high price of provision and the low rate of labour, grievances from the want of employ and a variety of other causes were usually alleged for the risings of the people, but on the present occasion, no grievance exists, and the fomenters of disorder are without such a pretension. ‘Down with the police’ is the cry, and demolish the protection of the city is the pursuit.

The article continues:

In different parts of the town, prodigious mobs of people were assembled and the avowed purpose of their tumultuous rising was declared in the vehemence of their execrations against the police. ‘Down with the police, five pounds for a policeman’s head.’ They were the shouts which filled the streets. In Mary Street, no passenger could escape the shower of brick bats and paving stones intended for the police. In St Andrew’s Street, the scene was if possible more dreadful, for the mob, not content in driving the police watchman before them, proceeded to pull down the watch house in which he took refuge … [The men] were obliged to fire and three of the rioters fell.

The riot only concluded on the Thursday, due to military intervention, when:

a party of men on horse dispersed the rioters and stood guard for the remainder of the night, which prevented more bloodshed and massacre … The blood of the unfortunate wretches who met their unhappy fate rests at the door of those few incendiaries who stimulated by their playful insignias unthinking persons to destruction.

A Forgotten Tragedy on Hammond Lane, 1878

Donal Fallon

On Church Street in Dublin 7, a memorial marks the location where two tenements collapsed in September 1913, killing seven people and injuring dozens more. Flowers are left beside it on occasion, and in 2013 the Stoneybatter and Smithfield People’s History Project organised a local commemoration to remember those who had lost their lives there a century ago.

Numerous plaques on Church Street and in its environs also record the area’s strong links to Ireland’s revolutionary past. The Fianna Éireann activist Seán Howard, shot delivering dispatches during Easter Week, is remembered by a plaque unveiled by the National Graves Association, in addition to a more recent memorial from the Cabra Historical Society unveiled during the 1916 centenary. At St Michan’s Church, a plaque remembers John and Henry Sheares, prominent members of the Dublin Society of United Irishmen, who were hanged at the Newgate Prison for their role in planning insurrection in 1798.

In an area so rich with history, and in which history is so well marked, it is curious that nothing remembers one of the greatest industrial accidents in the history of the city, and the dreadful events of 27 April 1878. On Hammond Lane, which sits between Church Street and Bow Street, a powerful boiler explosion within Strong’s iron foundry was enough to bring tenements, public houses and industrial buildings crashing to the ground, while also resulting in the loss of fourteen lives. One newspaper described the day as ‘a catastrophe, perhaps exceeding in its calamitous nature and deplorable consequences, any event which happened in Ireland within recent years’.

The Poverty of St Michan’s

Hammond Lane sat within the parish of St Michan’s, which was long regarded as one of Dublin’s poorest and most densely populated parishes. One early nineteenth-century guide to the city warned that the residents of this district were ‘all of the poorest classes of society; and so proverbial is this parish for its poverty, that the advertisement of the annual charity sermon is headed by the words ‘the poorest parish in Dublin’. Nugent Kennedy, speaking to the Social Science Association in Dublin in 1861, referred specifically to the parish of St Michan’s as being among the very worst districts in the city, insisting much of it was ‘only fit to be demolished’. To him, ‘the people inhabiting these localities look as though stricken by the plague’.

By the time of the 1862 Thom’s Almanac, a year after Kennedy’s comments, Hammond Lane was home to a grocer, stables and two provision dealers, but it was clear who the primary employers were. At number seven, James Tyrell operated an iron mills. At numbers eight and nine, John Strong and sons operated a ‘foundry and ironworks, millwrights and engineers’. Amid these centres of work were tenements: numbers four to six, numbers eleven to fourteen and numbers seventeen to twenty-five were all tenement accommodation. This would remain the urban fabric of the street for decades to come.

Iron foundries were a significant employer of working-class Dubliners throughout the nineteenth century. While there were thirteen iron foundries in Dublin in 1824, the number had risen to twenty-nine by 1850.

The Explosion of 27 April 1878

At around half one on 27 April 1878, an explosion in the area of Hammond Lane caused panic and confusion. The Freeman’s Journal noted that rumours abounded in the city, as:

a terrific explosion was heard in the neighbourhood of Arran Quay and Church Street and in the Four Courts. Reports spread rapidly, and were, it is needless to say, of a very varied character. One was that the Bow Street Distillery had been blown up; another that four houses had fallen. Those in the vicinity of Hammond Lane knew too well what had happened.

At Strong’s foundry, the steam boiler had exploded, bursting with a force that led The Irish Times to describe how ‘one of the front walls of the foundry was rent into pieces, and literally blown into the street’. A part of the boiler was described as having been ‘violently hurled into a gateway opposite. Had it struck one of the houses filled with alarmed men, women and children, a terrible addition might have been made to the dreadful calamity.’

The risk of such boiler explosions at the time was well-known. Publications like The Engineer repeatedly wrote of the risks of such incidents occurring, and in Britain lives were lost in such industrial accidents. Fifteen lives were lost at the Town and Son Factory at Bingley in West Yorkshire in June 1869 owing to a boiler explosion there, while an earlier explosion at Fieldhouse Mills in Rochdale had claimed ten lives in 1855. In New York, the dreadful Hague Street explosion in 1850 had claimed more than sixty lives. In Dublin, the Freeman’s Journal was furious that ‘of late years, boiler explosion has followed boiler explosion with alarming and increasing frequency’.

The loss of life on Hammond Lane could have been worse, as many men had left Strong’s at one o’clock on their break. At the time of the explosion, the lane was described as ‘deserted, save by a few passers-by and some children playing in front of the ill-fated walls’. One premises destroyed by the powerful blast was Duffy’s public house, opposite the foundry, where the proprietor, Patrick Duffy, and two of his children were killed.

Mr Duffy was a well-known figure in Dublin, having held the position of warder in one of the Metropolitan convict depots, and having been employed by Dublin Corporation in the past. His public house, after the blast, was described as ‘a shambles, having collapsed like a pack of cards, burying those inside’. Two of the tenement buildings on the street were destroyed too – three-storey buildings that housed some of the poorest workers in Dublin.

The Response to the Blast

In the immediate aftermath of the explosion, the Dublin Fire Brigade arrived on the scene and began seeking survivors in the rubble, as well as removing remains. Under the stewardship of James Robert Ingram, a veteran of the New York Fire Department, the fire brigade provided an important service with very meagre resources. The first task for firefighters was removing those members of the public who wished to assist from the scene of the carnage. More often a hindrance than a help to a rescue operation, the distraught public would remain a sight on the street in the days that followed. One hundred men from the 91st Highlanders arrived from the nearby Royal Barracks and assisted the firefighters in removing debris.

When the tragedy came before the coroner’s court, details of how the fourteen had lost their lives emerged: twelve had suffocated and two were crushed. There were also more than thirty people who were injured in the blast, some of whom were maimed for life. Dr Robert Martin, the resident surgeon of the Richmond Hospital, detailed the horrific sights that followed the tragedy, while others recounted the scenes of people alive under the ruins of the blast, fighting for survival.

Yet if there was hope for answers, people were to be left disappointed. Dublin Fire Brigade historians Geraghty and Whitehead note that:

The engineer’s report stated that the boiler was not properly maintained and was weakened by corrosion. No independent engineer had examined the boiler in the previous two years … There were no statutory regulations under the Factories Act 1875 for the inspection of boilers, although such provision had been demanded from parliament by engineers throughout the United Kingdom.

In the end, nobody was found negligent. Instead, it was found that ‘the explosion was the result of a defective condition of one of the boiler plates, which was externally corroded to a dangerous extent … We cannot attribute any criminal negligence to the Messrs Strong, who appear to have taken all reasonable care to keep the boiler in effective condition’.

In the immediate aftermath of the tragedy, there was an outpouring of support for the families of the victims, and the dozens of people left homeless. The Grafton Theatre of Varieties, a popular institution in the city, raised hundreds of pounds for those who had lost so much, and the Lord Mayor of Dublin appealed to the people of the city to reach into their pockets. Still, the tragedy quickly disappeared from the pages of Dublin newspapers, leaving the people of Hammond Lane to put the pieces back together again.

Today, there is no trace of the foundry. In 1973, the Hammond Lane foundry closed, resulting in the loss of just under two hundred jobs, and in recent years much of Hammond Lane has been behind hoardings, awaiting ever-delayed redevelopment and plans for a new family law courts building. Memorials like that to the victims of the Church Street tenement collapse serve to remind us of the challenges and struggles of working-class people in history, and it is undoubtedly time the victims of the foundry explosion were remembered in some way.

From Grandeur to Ruin: the Story of Sarah Curran’s Home in Rathfarnham

Sam McGrath

The ruins of a Georgian home lie hidden in the middle of a 1970s housing development in Rathfarnham. Known as the Priory, this house, which stood for at least 150 years, played an integral role in what has been called ‘the greatest love story in Irish history’ – that of Sarah Curran and Robert Emmet. Its journey from a beautifully well-kept homestead to a vandalised ruin is yet another example of the Irish state and other bodies failing to preserve buildings of historical interest.

The house was linked to secret societies, wild parties, underground passages, fatal accidents, ghosts, secret rooms, and a long-running quest for a forgotten grave. Its story has all the hallmarks of a fantastic melodramatic thriller.

In 1790, the famed barrister and politician John Philpot Curran took possession of a stately house off the Grange Road in Rathfarnham. He renamed it the Priory after his former residence in his hometown of Newmarket, Co. Cork. A constitutional nationalist, Curran defended various members of the United Irishmen who came to trial after the failed 1798 rebellion.

William O’Regan described the view from the second floor of the Priory in his 1817 biography of Curran as:

The mystical entrance into The Priory from the book Footprints of Emmet by J.J. Reynolds (1903).

of interminable expanse, and commanding one of the richest and best-dressed landscapes in Ireland, including the Bay of Dublin, the ships, the opposite hill of Howth, the pier, and lighthouse, and a long stretch of the county of Dublin …

O’Regan described the house as ‘plain, but substantial, and the grounds peculiarly well laid out and neatly kept’.

Curran was a founding member of an elite patriotic drinking club called the Monks of the Screw (aka the Order of St Patrick), which was active in the late 1700s. The membership, numbering fifty-six, included politicians (Henry Grattan), judges (Jonah Barrington), priests (Fr Arthur O’Leary), and lords (Townshend). Many were noted for their strong support of constitutional reform and self-government for Ireland. The club used to meet every Sunday in a large house on Kevin Street owned by Lord Tracton.

View of The Priory ruins in 1988 in the Hermitage housing estate, Rathfarnham (Image: Patrick Healy (southdublinlibraries.ie))

Named the ‘prior’ of the Monks, Curran used to chair their meetings, at which members wore cassocks. It was he who wrote their celebrated song, the first verse of which is:

When Saint Patrick this order established,

He called us the Monks of the Screw

Good rules he revealed to our abbot

To guide us in what we should do;

But first he replenished our fountain

With liquor the best in the sky;

And he said on the word of a saint

That the fountain should never run dry.

Curran also used to host the Monks at his home in Rathfarnham, in a special room situated to the right of the hall door. The two outside legs of the table at which they would sit were carved as satyrs’ legs. Between them was the head of Bacchus, god of the grape harvest and winemaking, and the three were wound together by a beautifully carved grapevine. An 18 September 1942 Irish Times piece said an elegant ‘mahogany cellarette in an arched recess in another part of the room was capable of holding many dozens of wines’.

The parties, as can be imagined, were all-night affairs. Wilmot Harrison, in his 1890 book Memorable Dublin Houses, wrote that: ‘Ostentation was a stranger to [Curran’s] home, so was formality of any kind. His table was simple, his wines choice, his welcome warm, and his conversation a luxury indeed …’ The house was allegedly haunted by a mischievous ghost, who spent most of his time in a secret room of the house, which was eventually closed up by Mrs Curran.

Tragedy struck on 6 October 1792, when Curran’s youngest daughter Gertrude accidentally fell from a window of the house and was killed. Devastated at the loss of his favourite child, Curran decided to bury his daughter not in a graveyard but in the garden adjacent to the Priory, so that he could gaze upon her final resting place from his study in the house. A small, square brass plaque was put on the grave’s stone slab reading:

Here lies the body of Gertrude Curran

fourth daughter of John Philpot Curran

who departed this life October 6, 1792

Age twelve years.

Historian Richard Robert Madden, in his 1842 book The United Irishmen: Their Lives and Times, wrote that Sarah Curran’s last request on her deathbed was to be buried ‘under the favourite tree at The Priory, beneath which her beloved sister was interred’. However, her father did not agree to this. Lord Cloncurry told Madden that this was because he had been criticised for burying Gertrude in unconsecrated ground. The fact that Curran also disowned and essentially banished his daughter Sarah no doubt had something to do with it as well.

The story of Robert Emmet and Sarah Curran is known to many. In a nutshell, the Irish nationalist Emmet was introduced to the beautiful Sarah through her brother Richard, whom he knew from Trinity College. They fell madly in love, but Curran’s father did not approve of their relationship. After clandestine meetings and many love letters, they secretly got engaged in 1802. Following his abortive rebellion against British rule the following year, Emmet fled to the Dublin Mountains but was caught after he tried to visit Sarah at the Priory. From his cell in Kilmainham Gaol, he wrote a letter – addressed to ‘Miss Sarah Curran, the Priory, Rathfarnham’ – and gave it to a prison warden whom he thought he could trust to deliver it. Instead, it was handed to the authorities, and Curran’s cover was blown. The Priory was raided by the British, and Sarah’s sister Amelia only just succeeded in burning Emmet’s letters.

Emmet, aged 25, was hanged and beheaded on Thomas Street in Dublin 8 on 20 September 1802. Curran, disowned by her father, moved to Cork, where she married a captain in the Royal Marines. Accompanying him to Sicily, where he was stationed, she contracted tuberculosis. They returned to Kent, England, where she died in 1808, aged just 36. She was laid to rest in the family plot in Newmarket.

John Philpot Curran, a broken man after the deaths of two of his daughters, was pushed further to the edge when his wife left him for another man. From all accounts, he cut a lonely figure, wandering the gardens of the house at all hours of the night, and weeping by his daughter’s grave. He lived in the Priory on his own until his death in 1817.

What follows is the story of the once magnificent Priory’s slow journey into nothingness. Under the name ‘Swart’, a journalist had a long article in the 14 October 1922 Irish Independent titled ‘John Philpot and the Priory – Some Incidents Recalled’:

Nestling amidst its groves of beech and chestnuts, the Priory still bravely shows a semblance of its former prosperous condition. What tales of revelry or love its old walls might repeat! What days of joys and sorrow in the lives of its occupants has it beheld!

Swart continued:

We approach it through an open drive, guarded by old-fashioned gates of evident antiquity. Standing on the now moss-grown carriage-sweep before the front door one is conscious of a delicious air of mystery of breathing over all. The grove of tall beech trees flanking the eastern gable, the great dark cedar beside them, shading the door which leads to the gardens at the rear, the spreading timbers of chestnut outside the western gates are silent sentinels which will never betray the secrets of the days that are gone.

Apparently able to gain access to the house easily enough, he wrote that, looking from the front windows:

over the high tree tops in the fields beyond, a misty vision of the city stretches far below, and the distant outlines of Howth Summit and the northern coast become faintly visible. At night the tiny beacons from the harbour bar glow like fair lanterns through the dark

Clearly deeply interested in the house itself as well as the Curran family, Swart wrote that:

the years have dealt ruthlessly with the gardens of the Priory. Once the fond care of the great orator, he converted them into a veritable Eden. Often when touched by the melancholic depression which seems inseparable from the Irish character, he would wander out at midnight to pace a fitful hour through chosen leafy haunts.

Gertrude’s grave marker was still visible in 1922, Swart writing that:

in a tiny grove … a desecrated tombstone still marks a hallowed spot. It is the last resting place of one who in a short life brought great sweetness to those held her most dear … When she died in her twelfth year, he could not bear the thought of separating her from the surroundings to which she had so much gladness. They buried [her] in sight of the old house and with it much of the worldly hopes and aspirations of her sorrowing father.

The Sunday Independent’s ‘Special Commissioner’ focused his weekly column on 23 November 1924 on the Priory: