9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The O'Brien Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

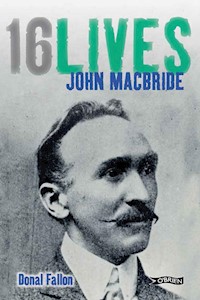

Major John MacBride, who was Born in Westport, County Mayo in 1868, was a household name in Ireland when many of the leaders of the Easter Rising were still relatively unknown figures. As part of the 'Irish Brigade', a band of nationalists fighting against the British in the Second Boer War, MacBride's name featured in stories in the Freeman's Journal and Arthur Griffith's United Irishman. The Major went on to travel across the United States, lecturing audiences on the blow struck against the British Empire in South Africa. His marriage to Maud Gonne, described as 'Ireland's Joan of Arc', led to further notoriety. Their subsequent bitter separation involved some of the most senior figures in Irish nationalism. MacBride was dismissed by William Butler Yeats as a 'drunken, vainglorious lout; Donal Fallon attempts to unravel the complexities of the man and his life and what led him to fight in Jacob's factory in 1916. John MacBride was executed in Kilmainham Gaol on 5 May 1916, two days before his forty-eighth birthday.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

The16LIVESSeries

JAMES CONNOLLYLorcan Collins

MICHAEL MALLIN Brian Hughes

JOSEPH PLUNKETT Honor O Brolchain

EDWARD DALYHelen Litton

SEÁN HEUSTONJohn Gibney

ROGER CASEMENTAngus Mitchell

SEÁN MACDIARMADABrian Feeney

THOMAS CLARKEHelen Litton

ÉAMONN CEANNTMary Gallagher

THOMAS MACDONAGHShane Kenna

WILLIE PEARSERoisín Ní Ghairbhí

CON COLBERTJohn O’Callaghan

JOHN MACBRIDEDonal Fallon

MICHAEL O’HANRAHANConor Kostick

THOMAS KENTMeda Ryan

PATRICK PEARSERuán O’Donnell

DONALFALLON – AUTHOR OF16LIVES: JOHN MACBRIDE

Donal Fallon is a lecturer and historian based in Dublin. Co-founder of the popular social history website ‘Come Here To Me’, his previous publications include The Pillar: The Life and Afterlife of the Nelson Pillar (New Island, 2014). He is currently completing a PhD on republican commemoration and memory in 1930s Ireland.

LORCAN COLLINS – SERIES EDITOR

Lorcan Collins was born and raised in Dublin. A lifelong interest in Irish history led to the foundation of his hugely-popular 1916 Walking Tour in 1996. He co-authored The Easter Rising: A Guide to Dublin in 1916 (O’Brien Press, 2000) with Conor Kostick. His biography of James Connolly was published in the 16 Lives series in 2012. He is also a regular contributor to radio, television and historical journals. 16 Lives is Lorcan’s concept and he is co-editor of the series.

DR RUÁN O’DONNELL – SERIES EDITOR

Dr Ruán O’Donnell is a senior lecturer at the University of Limerick. A graduate of University College Dublin and the Australian National University, O’Donnell has published extensively on Irish Republicanism. Titles include Robert Emmet and the Rising of 1803, The Impact of 1916 (editor), Special Category, The IRA in English prisons 1968–1978 and The O’Brien Pocket History of the Irish Famine. He is a director of the Irish Manuscript Commission and a frequent contributor to the national and international media on the subject of Irish revolutionary history.

DEDICATION

To my parents, Las and Maria. I owe so much to you both

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

As the 16 Lives series nears its conclusion, I want to thank Lorcan Collins and Ruan O’Donnell for inviting me to participate in this exciting project. The series of books is a very meaningful contribution, and indeed a lasting one, to the centenary of the 1916 rebellion.

Historians can only hope to add to the existing body of work on any subject, and in the case of Major John MacBride, a few researchers deserve particular praise for the works from which this study drew upon. Firstly, Donal P. McCracken has done hugely important work on the Irish and the Second Boer War, and indeed on the history of the Irish Diaspora in South Africa. Anthony J. Jordan has brought important primary source materials on MacBride to the public awareness, and has drawn attention to the presence of the MacBride papers in the National Library of Ireland, when they were discovered hidden away in the papers of veteran Fenian Fred Allan. The Cathair na Mart journal, which celebrates the local history of Westport and its environs, has also played an important role in telling the story of the MacBride family.

I owe enormous gratitude to all at The O’Brien Press, and to Aoife Barrett of Barrett Editing. Her insights and hard work played no small part in shaping this book. My family have been very helpful and supportive throughout, as they always are, and the encouragement of my parents has always driven me forward.

The staff at various archival institutions and libraries, in particular the Dublin City Library and Archive, the National Library of Ireland and the National Archives of Ireland, continue to do great work in the face of endless cutbacks to their services. It is a joy to research history in Ireland when these institutions, and others like them, are in the hands of people who are passionate about the collections they hold. Long may that stay the case.

My co-workers (or co-walkers) at Historical Walking Tours of Dublin deserve mention. It is a joy to work alongside people who are passionate about history. I am eternally grateful to Tommy Graham for taking me on. Likewise, Trevor White and all in The Little Museum of Dublin deserve thanks for the great support they have shown to me. Ciarán Murray and Sam McGrath of the ‘Come Here To Me’ website, which I co-founded, are two of the best friends anyone could ask for and keepers of Dublin’s history in their own way.

Lastly, my partner Aoife deserves a special mention. She has listened to me talk of nothing but Boers, Fenians, poets and rebellion for quite some time now. She is my anchor, and brings me great joy in life.

Go raibh maith agaibh go léir.

16LIVESTimeline

1845–51. The Great Hunger in Ireland. One million people die and over the next decades millions more emigrate.

1858, March 17. The Irish Republican Brotherhood, or Fenians, are formed with the express intention of overthrowing British rule in Ireland by whatever means necessary.

1867, February and March. Fenian Uprising.

1870, May. Home Rule movement founded by Isaac Butt, who had previously campaigned for amnesty for Fenian prisoners.

1879–81. The Land War. Violent agrarian agitation against English landlords.

1884, November 1. The Gaelic Athletic Association founded – immediately infiltrated by the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB).

1893, July 31. Gaelic League founded by Douglas Hyde and Eoin MacNeill. The Gaelic Revival, a period of Irish Nationalism, pride in the language, history, culture and sport.

1900, September.Cumann na nGaedheal (Irish Council) founded by Arthur Griffith.

1905–07.Cumann na nGaedheal, the Dungannon Clubs and the National Council are amalgamated to form Sinn Féin (We Ourselves).

1909, August. Countess Markievicz and Bulmer Hobson organise nationalist youths into Na Fianna Éireann (Warriors of Ireland) a kind of boy scout brigade.

1912, April. Asquith introduces the Third Home Rule Bill to the British Parliament. Passed by the Commons and rejected by the Lords, the Bill would have to become law due to the Parliament Act. Home Rule expected to be introduced for Ireland by autumn 1914.

1913, January. Sir Edward Carson and James Craig set up Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) with the intention of defending Ulster against Home Rule.

1913. Jim Larkin, founder of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU) calls for a workers’ strike for better pay and conditions.

1913, August 31. Jim Larkin speaks at a banned rally on Sackville (O’Connell) Street; Bloody Sunday.

1913, November 23. James Connolly, Jack White and Jim Larkin establish the Irish Citizen Army (ICA) in order to protect strikers.

1913, November 25. The Irish Volunteers founded in Dublin to ‘secure the rights and liberties common to all the people of Ireland’.

1914, March 20. Resignations of British officers force British government not to use British army to enforce Home Rule, an event known as the ‘Curragh Mutiny’.

1914, April 2. In Dublin, Agnes O’Farrelly, Mary MacSwiney, Countess Markievicz and others establish Cumann na mBan as a women’s volunteer force dedicated to establishing Irish freedom and assisting the Irish Volunteers.

1914, April 24. A shipment of 25,000 rifles and three million rounds of ammunition is landed at Larne for the UVF.

1914, July 26. Irish Volunteers unload a shipment of 900 rifles and 45,000 rounds of ammunition shipped from Germany aboard Erskine Childers’ yacht, the Asgard. British troops fire on crowd on Bachelors Walk, Dublin. Three citizens are killed.

1914, August 4. Britain declares war on Germany. Home Rule for Ireland shelved for the duration of the First World War.

1914, September 9. Meeting held at Gaelic League headquarters between IRB and other extreme republicans. Initial decision made to stage an uprising while Britain is at war.

1914, September. 170,000 leave the Volunteers and form the National Volunteers or Redmondites. Only 11,000 remain as the Irish Volunteers under Eóin MacNeill.

1915, May–September. Military Council of the IRB is formed.

1915, August 1. Pearse gives fiery oration at the funeral of Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa.

1916, January 19–22. James Connolly joins the IRB Military Council, thus ensuring that the ICA shall be involved in the Rising. Rising date confirmed for Easter.

1916, April 20, 4.15pm.The Aud arrives at Tralee Bay, laden with 20,000 German rifles for the Rising. Captain Karl Spindler waits in vain for a signal from shore.

1916, April 21, 2.15am. Roger Casement and his two companions go ashore from U-19 and land on Banna Strand. Casement is arrested at McKenna’s Fort.

6.30pm.The Aud is captured by the British navy and forced to sail towards Cork Harbour.

22 April, 9.30am.The Aud is scuttled by her captain off Daunt’s Rock.

10pm. Eóin MacNeill as chief-of-staff of the Irish Volunteers issues the countermanding order in Dublin to try to stop the Rising.

1916, April 23, 9am, Easter Sunday. The Military Council meets to discuss the situation, considering MacNeill has placed an advertisement in a Sunday newspaper halting all Volunteer operations. The Rising is put on hold for twenty-four hours. Hundreds of copies of The Proclamation of the Republic are printed in Liberty Hall.

1916, April 24, 12 noon, Easter Monday. The Rising begins in Dublin.

16LIVES MAP

16LIVES- Series Introduction

This book is part of a series called 16 LIVES, conceived with the objective of recording for posterity the lives of the sixteen men who were executed after the 1916 Easter Rising. Who were these people and what drove them to commit themselves to violent revolution?

The rank and file as well as the leadership were all from diverse backgrounds. Some were privileged and some had no material wealth. Some were highly educated writers, poets or teachers and others had little formal schooling. Their common desire, to set Ireland on the road to national freedom, united them under the one banner of the army of the Irish Republic. They occupied key buildings in Dublin and around Ireland for one week before they were forced to surrender. The leaders were singled out for harsh treatment and all sixteen men were executed for their role in the Rising.

Meticulously researched yet written in an accessible fashion, the 16 LIVES biographies can be read as individual volumes but together they make a highly collectible series.

Lorcan Collins & Dr Ruán O’Donnell,

16 Lives Series Editors

CONTENTS

Introduction

At the beginning of the twentieth century, when many of the leaders of the Easter Rising were still relatively unknown figures on the peripheries of Irish political and cultural life, the name Major John MacBride was already becoming familiar in Ireland, and indeed to the Irish nationalist Diaspora.

MacBride was part of a small band of armed men known as the ‘Irish Brigade’, uitlanders (or foreigners) in the Transvaal. During the Second Boer War (1899–1902) they had taken up arms to fight against what they saw as British imperial aggression in South Africa. Transvaal flags flew in the breeze in Dublin and tens of thousands demonstrated across the island in sympathy with the Boer cause. It was a war that sparked something in nationalist Ireland, and moved W. B. Yeats to write, ‘the war has made the air electrical just now.’1

W. B. Yeats plays a significant part in the story of John MacBride. Though the two knew little of one another in person, they moved in the same nationalist circles, were both disciples of the veteran Fenian John O’Leary and, most crucially, both fell in love with the nationalist campaigner Maud Gonne. The popular image of John MacBride today has been derived from Yeats and his poem ‘Easter 1916’, in which MacBride assumes the role of a ‘drunken, vainglorious lout’. Gonne would write that the poem was ‘not worthy of Willie’s genius, and still less of the subject.’2

The marriage of John MacBride and Maud Gonne was, in a single word, disastrous. Relatives of each, and indeed influential Irish nationalists, had urged the two not to marry. During their divorce case, allegations of violence, drunkenness and sexual impropriety were levelled against MacBride, though of these only drunkenness was found against him in court. The bitter separation that followed left MacBride estranged from his wife and distant from his young son Seán. They remained in France while MacBride returned to Ireland. In recent years the discovery of John MacBride’s papers in the collections of Fenian leader Fred Allan has enabled historians and biographers to re-examine the disastrous marriage and the controversial separation that followed. Deposited in the National Library of Ireland (NLI), the papers give crucial new insights into a traumatic chapter in the lives of both Gonne and Mac-Bride.

John MacBride had little doubt that he would be executed for his role in the Easter Rising, even though he was not a member of the Irish Volunteers, and most likely stumbled across the insurrection by a degree of chance on 24 April 1916. Having taken up arms in the conflict in South Africa, he knew his past would stand against him. He was proved correct.

General Sir John Maxwell, the British general sent to Dublin to suppress the insurrection, wrote to Prime Minister Herbert Asquith in the aftermath of the Rising. He began the justification for MacBride’s execution by stating, ‘This man fought on the side of the Boers in the South African war of 1899 and held the rank of Major in that Army, being in command of a body known as the Irish Brigade.’3 Maxwell was himself a veteran of the same Boer War in which MacBride had fought.

John MacBride was duly executed on 5 May 1916, when he was placed in front of a firing squad in the stone-breakers’ yard of Kilmainham Gaol. This biography sets out to demonstrate that MacBride was an altogether more complex figure than the caricature of the man depicted in both the poetry and studies of the period has allowed him to be. It seeks to look at the context in which MacBride emigrated to South Africa, showing the emergence of a separatist Irish nationalist community there, even before the outbreak of the Second Boer War in 1899. It examines the separation of MacBride and Gonne in detail and also examines MacBride’s return and readjustment to Ireland in the aftermath of that sad affair, in a period when great change was underway. Lastly, it draws on the testimony of the men and women who were there in 1916 and who fought alongside MacBride, to demonstrate that the leadership skills he developed in South Africa were apparent during that very eventful week on the streets of Dublin.

Notes

1 Quoted in Elleke Boehmer, Empire, the National, and the Postcolonial, 1890–1920: Resistance in Interaction (Oxford University Press, 2005), p26.

2 Maud Gonne’s correspondence with Irish American lawyer John Quinn, quoted in Nancy Cardozo, Maud Gonne (New Amsterdam Books, 1990), p92.

3 ‘Short history of the rebels on whom it has been necessary to inflict the supreme penalty’ sent by General Sir John Maxwell to Herbert Asquith, 11 May 1916. Reprinted in Brian Barton, The Secret Court Martial Records of the Easter Rising (The History Press, 2010), p209.

Chapter 1 • • • • •

The Development of a Young Fenian

His great-grandfather took part in the insurrection of 1798; his grandfather followed the fortunes of the Young Irelanders who first struggled for the establishment of an Irish parliament and ultimately drifted into revolution; his father and uncles were members of the Irish Revolutionary Brotherhood of 1867 … Irish patriotism was therefore, so to say, in his blood.4

While preparing for his bitter and public separation from Maud Gonne, John MacBride penned the above words in a brief autobiography for his legal team. While the blood of Fenianism certainly flowed in MacBride’s veins, it came not from his father but rather from his mother, Honoria Gill’s, side. John MacBride’s father, Patrick, was in fact the captain of a merchant schooner. He was of Ulster-Scots Protestant heritage and hailed from Glenshesk in Antrim. Patrick had settled in Westport and married into the respected Gill family in the mid-nineteenth century. They were the years when the Quay of Westport was alive with ships and commerce, bringing men like Patrick to the town. In the 1960s John Davis O’Dowd, a relative of John MacBride, would recall the Quay’s former glory:

If you ever go down the Quay Hill to the Custom House and look down that half-mile, or more, of desolation, you will have some conception of the sadness it brings to one who saw it over seventy years ago, when the tall ships lined the Quay.5

Though earlier than O’Dowd’s recollections, the Quay was bustling too in the time of John MacBride’s arrival. Born on 7 May 1868, John was the youngest of five children. Blessed with a head of red hair, ‘Foxy Jack’, as John would become known, was the ‘child’ of the family. MacBride’s elder siblings were all boys, and the brothers would lead interesting and varied lives, though they shared one thing in common – all held strong nationalist convictions. Joseph, the eldest of John’s brothers, was eight years his senior. He would find work with the Harbour Commissioners, later becoming a Sinn Féin TD in 1918 and remaining active in Irish politics throughout his life. Anthony would become an important figure in the Irish republican movement in London, establishing himself as a Doctor there before later returning to Ireland where he continued his medical pursuits. His achievement in passing the Royal University Degree Examination in Medicine in 1889 was reported in the Connaught Telegraph, indicating the standing of the family locally. It congratulated the son of the respected Honoria MacBride of Westport Quay ‘on his successful collegiate course, which is highly creditable to a genial man so young.’6 John’s third brother, Francis, emigrated to Australia, while Patrick eventually assumed control of the family business in Westport.

MacBride’s mother Honoria was a woman who was of strong Mayo stock, and one of nine children herself. Two of her cousins had taken part in the doomed Fenian rebellion of 1867. Éamon de Valera would praise her while speaking in the town at the unveiling of a plaque to John MacBride in 1963:

It is said that there is an island in Clew Bay for every day of the year. That may be so, but for John MacBride there was one island in particular: Island More. His mother’s people came from Island More. She was Honoria Gill: a truly remarkable woman, forceful, kind, but always masterful. There was a strong Fenian tradition in the Gill family. James Stephens, the Fenian, was a friend. Martin Gallagher who married a Gill was the Head Centre of the Fenians in Mayo; he made a spectacular escape to America and later took part in the Fenian invasion of Canada in 1870.7

At only thirty-five-years of age, John MacBride’s father Patrick died of typhus in 1868, leaving Honoria with both the raising of the family and the maintenance of the family business. To lose her husband in the same year as the birth of her youngest son left Honoria in a difficult position but the family operated as a wholesale grocer, described also as a ‘tea, wine and spirit merchant’ and she managed to keep the business going. It remained a commercially successful enterprise that allowed Honoria to educate her children well and to give her sons a degree of comfort in life.

Honoria would ultimately outlive her youngest son, passing away in 1919, having taken the news of his execution with great dignity. She also lived to see Joseph, elected as the first Sinn Féin TD for the constituency in the 1918 elections. At the time of her death, the high regard in which she and her family were held was evident from the outpouring of local grief. The Castlebar Board of Guardians passed a resolution of sympathy, and one member of the board noted that ‘I have known the MacBride family for many years and I can say that there is not a more respected family in Mayo.’8

The MacBride’s business thrived in John’s early years as Westport in the nineteenth century stood in stark contrast to more impoverished areas of Mayo. It had once been the seat of the Marquis of Sligo, who owned an extraordinary estate of 114,881 acres, making it the largest estate in Mayo and one of the largest on the island. The county was devastated by the famine of the 1840s and poverty remained a fact of life for many in Mayo in subsequent decades.

In 1879 The Freeman’s Journal reported that in a summer of intense weather and misery ‘the two props of the Mayo farmer’s homestead have collapsed miserably upon his head. The potatoes are bad – the turf is worse.’9 Westport itself became the staging ground for significant agitation from the poor and landless, with thousands gathering on the edge of the town to hear Charles Stewart Parnell speak in June of that same year. Despite the meeting being condemned in no uncertain terms by the Catholic Archbishop of Tuam, John MacHale, there was much anger among the Mayo poor that day, enough to ignore clerical denunciation and attend the rally. The people listened as Parnell urged them that ‘you must show the landlords that you intend to keep a firm grip on your homesteads and lands. You must not allow yourselves to be dispossessed as you were dispossessed in 1847.’10 Also addressing the meeting was Michael Davitt, a native of Mayo, who would become synonymous with the ‘Land War’ in Ireland and the battle of the rural peasantry and landless for better rights as tenants. The crowd also listened to militant speakers such as the Fenian Michael M. O’Sullivan, who informed them that ‘moral force’ had to be backed up by ‘the power of the sword’11.

While the messages of class discontent resonated with the poor of the county and province on that June day, the MacBride family were of a different stock, as small business owners in the town. John was educated firstly by the Christian Brothers in Westport, before attending St Malachy’s College in Belfast. The oldest Catholic grammar school in Ulster, St Malachy’s was established in the 1830s in the wake of Catholic Emancipation. Former graduates included Sir Charles Gavan Duffy, a founding member of the radical newspaper The Nation in the 1840s, while Eoin MacNeill, one of the founders of the Gaelic League and a man who would come to play no small part in the story of the 1916 Rising, was a contemporary of MacBride’s. The school, it has been noted, ‘was long regarded as the jewel in the crown of Catholic education in the town, producing future clerics and professional men alike.’12 While St Malachy’s College was a Catholic institution in a predominantly Protestant city, there does not appear to have been much nationalistic feeling among the student body. Patrick McCartan, later a member of the Supreme Council of the IRB, attended the school in the 1890s and remembered:

I wouldn’t say there was much nationalism there. I did not see any signs of nationalism amongst the students. There was one professor who started a branch of the Gaelic League there, named O’Cleary. He was not much good as a teacher, as a matter of fact, very bad, because he used to do more talking than teaching during class hours.13

Work opportunities for the young John, as a teenage graduate of St Malachy’s, came firstly via his family connections. They helped arrange an apprenticeship for him with John Fitzgibbon, a draper based in Castlerea, County Roscommon. MacBride claimed in his brief autobiographical sketch that it was as a young man of fifteen that he ‘took an oath to do my best to establish a free and independent Irish nation’, and that by the time he had arrived in the capital he was ‘associated with the party known as ‘Advanced Nationalists’, a term used to describe those whose nationalism favoured a republican approach, which stood in contrast with the constitutional nationalism of the Home Rule movement.14

The oath to which MacBride referred to taking at this point in his life was, of course, the Fenian oath of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), a secret, oath-bound society which strove to bring about an independent Irish republic. Variations of this oath had been in place since the establishment of the IRB in March 1858, and it was a pledge MacBride would prove faithful to, a promise to do all in his power to establish the independence of his country:

I, John MacBride, in the presence of Almighty God, do solemnly swear allegiance to the Irish Republic, now virtually established; and that I will do my very utmost, at every risk, while life lasts, to defend its independence and integrity; and, finally, that I will yield implicit obedience in all things, not contrary to the laws of God, to the commands of my superior officers. So help me God. Amen’.15

There is evidence that MacBride did involve himself in radical nationalist activities during his time in Castlerea, despite being only in his mid-teens. Michael J. Cassidy, a native of Castlerea and a contemporary of MacBride, would comment decades later:

I remember the late Mr Fitzgibbon telling me during the Boer War that MacBride was an extreme nationalist when he worked as an apprentice in his shop. When I went to serve my time in Castlerea I met from time to time a number of the old Fenians and heard from them that MacBride, during his apprenticeship years, was very active organising the Brotherhood. During the Boer War his name was constantly mentioned in Castlerea.16

Fitzgibbon himself had nationalist political sympathies. He was active in his lifetime within the Gaelic League and the Land League movement, and became a United Irish League MP for South Mayo in 1910. MacBride spent some time working for Fitzgibbon in Castlerea, though by the apprentice draper’s own admission, ‘not finding that occupation congenial I left it and went back to St. Malachy’s for another year. After leaving St. Malachy’s I entered into the employment of Hugh Moore.’17

In Dublin, Hugh Moore maintained a wholesale druggists and grocer, and MacBride would spend several years with the firm, on and off. Years after his time in the Dublin chemist, a rather dismissive account of MacBride’s work there appeared in the magazine The Chemist and Druggist, essentially an in-house publication for those in the industry. When MacBride secured a degree of notoriety by fighting alongside the Boers in South Africa, a March 1900 edition of the magazine gloated:

When our correspondent was in Messrs. Hugh Moore & Co. drug-department MacBride came to the house from his mother’s shop in Westport (co. Mayo), which is a grocers, and he was put into the sundry-department, the stock there consisting only of grocery goods, such as coffee, biscuits, confectionery tinned meats etc. He never served an hour to the drug-trade, and in our correspondent’s opinion he would not know ‘the difference between Epsom salts and powdered opium’.18

The presence of a young, sixteen-year-old John MacBride is noted in the minute books of the Young Ireland Society (YIS), Dublin. Young Ireland was an organisation which troubled Dublin Castle authorities greatly as they believed it to be little more than a front for the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). On paper it was a nationalist literary and debating society, which publicly stated its goals as being to promote an interest in Irish literature, culture, history and debate. The premises of the YIS were raided by the Dublin Metropolitan Police on the day following its opening, indicating that the authorities were deeply troubled by the organisation’s very being.19

Participation in the Young Ireland Society and the cultural nationalist movement around it brought John MacBride into contact with a wide variety of nationalists, with differing opinions, including John O’Leary, Arthur Griffith and William Butler Yeats.

O’Leary was a veteran of the struggle and would become an important figure in MacBride’s life. The Tipperary native had certainly played his part in the Fenian movement, having spent years in English prisons and later in exile in the 1860s and 1870s. An unapologetic defender of armed separatism for much of his life, O’Leary would recall in his memoirs of the Fenian movement that:

Nations, any more than individuals, live not by bread alone. It was a proud and not undeserved boast of the Young Irelanders that they ‘brought back a soul into Éire’, but before Fenianism arouse that soul had fled. Fenianism brought it back again, teaching men to sacrifice themselves for Ireland instead of selling themselves and Ireland to England.20

If O’Leary was something of an elder statesman to the separatist movement, and an important inspiration to young activists such as John MacBride, it is important to note that O’Leary’s politics had evolved and changed with time. Indeed, even as he recalled his own political sentiments above, his political ideology had long since moved to a more comfortable centre. It has even been argued that he had become a ‘conservative … who favoured a constitutional monarchy.’21 O’Leary has perhaps best been defined as ‘a monument to an antique style of nationalism’.22 The veteran nationalist John Devoy recalled that ‘he thought there was so little difference between a moderate Republic and a liberal limited Monarchy.’23

O’Leary as a symbol and O’Leary as a contemporary political voice appear to have been two very different things. It was telling that John MacBride and Maud Gonne would later ask him to be the godfather of their son, indicating their respect for the aging figure and that they viewed his approval and indeed association with him as important. To a detective of Dublin Castle, O’Leary was ‘an old crank full of whims and honesty’24, but Irish historian and academic Roy Foster has suggested that for many O’Leary represented ‘a voice from the heroic past’, and that to William Butler Yeats he was an introduction to ‘the acceptable face of the extremist Fenian tradition’.25 In his autobiography, Yeats recalled of O’Leary that ‘he had the moral genius that moves all young people and moves them the more if they are repelled by those who have strict opinions and yet have lived commonplace lives’.26 O’Leary’s influence over individuals such as MacBride and Yeats would prove hugely significant, and it was the elder statesman who would later introduce Mac-Bride to the important US Fenian leader John Devoy.

Aside from the Young Ireland Society, another organisation John MacBride was active within when he moved to Dublin was the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA). He had involved himself in it with vigour during his youth in Mayo, and there was a real commitment to the organisation from the MacBride family. Joseph later served with the Connaught Council of the GAA and was elected as its President at its inaugural meeting in Claremorris in November 1902. In many ways the GAA served as both a sporting outlet and a social one for its membership, with very clear political undertones. Founded in 1884 by Michael Cusack, the organisation had approached Charles Stewart Parnell, Michael Davitt and Archbishop Croke of Cashel to serve as patrons. As W. F. Mandle has noted, this was a cunning move, as:

Virtually the whole spectrum of Irish nationalist politics was covered by the three, none of whom, apart possibly from Croke, who professed an admiration for handball, could be accounted sporting identities or having sporting interests. The political role and the political implications of the GAA were set from the start.27

To Archbishop Croke, the GAA would serve as a boulder against the increasing Anglicisation of Irish society. He warned that:

We are daily importing from England, not only her manufactured goods … but together with her fashions, her accents, her vicious literature, her music, her dances and her manifold mannerisms, her games also and her pastimes, to the utter discredit of our own grand national sports … as though we are ashamed of them.28

British authorities closely monitored this new organisation from its infancy. A Dublin Castle report from 1888 noted that ‘the question was not whether the association was a political one, but only to what particular section of Irish national politics it could be annexed.’29