Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

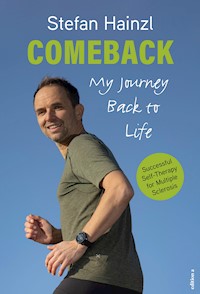

Showing weakness is a taboo in the world of elite sport, for the athletes as well as for the team behind the athletes. But Stefan Hainzl, doctor of the Austrian Nordic combined team, became weaker and weaker. Even after the devastating diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis, he hid the symptoms as best he could. At some point it was no longer possible. He fought the disease and gradually developed his own therapy, which restored his strength and rid him of symptoms. An inspirational and motivating book for those fighting against illness, even if it is thought to be incurable.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 209

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Stefan Hainzl, Laura Hainzl: Comeback

All rights reserved

© 2022 edition a, Vienna

www.edition-a.at

Cover photo: Gregor Hartl

Setting: Bastian Welzer

Revised english edition.

Originally published in german.

1 2 3 4 5 — 25 24 23 22

eISBN 978-3-99001-639-8

Stefan Hainzl

COMEBACK

My JourneyBack to Life

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

AT THE DESTINATION

THE LOWEST POINT

FACING THE TRUTH

HOPE DIES LAST

HIGHS AND LOWS

MY GENES ARE NOT MY FATE

VIENNESE HOPE

ALL EGGS IN ONE BASKET

THE BEGINNING OF THE END

COMEBACK TO LIFE

APPENDIX

For Paula, Mia and Lotta

INTRODUCTION

Readers of this book will immediately be struck by the unfiltered honesty of the author’s story. They will also see how one of his essential characteristics probably enabled him to write this book. Sometimes, this honesty is painful; sometimes it will raise a smile – but it will never fail to make readers feel close to somebody who has become one of the most special people to me ever since we began studying medicine together.

That’s how I met Stefan. All the students felt completely overwhelmed by an enthusiastic professor in a biochemistry seminar. When it was over, no-one even knew what the lecture has been about. A pink-haired guy in the second row put up his hand and said: “I’m sorry, but I didn’t understand a word of what you’ve just told us.” I was impressed that someone in this group of freshers had the courage to admit their lack of knowledge so openly. In the years, and meanwhile decades that followed, I learned that this student’s honesty and directness weren’t something he put on, but that they were an integral part of him that I experienced and valued many times, always with a new level of respect. Fortunately, the pink hair phase only lasted a few weeks.

This book is a testimonial of a doctor who became a patient himself. For a doctor, it can be harrowing to read about the encounters this patient, Stefan Hainzl, had with colleagues. The way, he describes his feelings shows what we doctors do to our patients with unempathetic comments that don’t take the individual into account. All doctors should read the description of patients' everyday occurrences, such as having to take lots of tablets or physical or psychological reactions to medication, so they can see what matters to patients beyond the doctor’s diagnostic perceptual horizon and how this determines the course of their illness and their handling of therapies.

For patients, no matter with what illness they turn to our medical system, it will certainly be a relief to learn that they are not alone with their inner turmoil and sometimes despair in a system that is so often not tailored to the individual.

And that it is always worth fighting. Stefan always was, and still is, a serious and determined fighter. I probably don’t know anyone who has such a high level of determination towards his own person as Stefan does. This determination holds immense opportunities, but also has its price, as the reader will discover. Stefan is somebody who can make decisions and live them. When the path he has chosen turns out to be the wrong one, such as his digression into the paleo diet, Stefan is able to make a new decision and not stick to the old one. That is another of the key characteristics that have accompanied him through life.

As a conventional medical practitioner and scientist, I obviously take a very critical approach to all medical content, especially when it comes to alternative treatment concepts. In the case of treatments for autoimmune diseases, whose geneses are still largely a mystery for the medical world, i.e., diseases like multiple sclerosis, where one's own immune system turns against the structures of the body, giant leaps have been made through the development of so-called disease-modifying drugs or biologicals and impressive therapeutic successes have been achieved. However, especially in the treatment of MS, these therapeutic agents often trigger strong allergic reactions that cause many patients to discontinue the treatment. This book highlights this problem at a very personal and individual level. I distinctly remember conversations with Stefan, where his fear of developing progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, a serious neurological complication while taking a certain drug, became clear. Something that sounds like pop philosophy is often criminally disregarded in the treatment of patients (and not just in conventional medicine): that the treatment of a disease doesn’t just consist of medication and direct effects and side effects, but that patients, with their thoughts and fears, have a much greater influence on this mode of action than we assume.

I am happy for all readers who hold this book in their hands and can now immerse themselves in Stefan’s story. This is his personal story. It’s also his personal medical history. As a doctor, Stefan is privileged to be able to make medical decisions on the basis of his long and intensive training, research and interpret primary literature by himself and, above all, make treatment decisions for himself and monitor them closely himself, for example using his lab results. This is particularly important for treatments, such as the vitamin-D therapy described that have a very narrow tolerance range and which, if not monitored, have already landed some patients in intensive care.

For me, Stefan’s way and his critical approach to aspects of his illness and life on so many levels has always been exemplary and admirable. I am happy and glad for him and everybody close to him about his health and the immense progress that he has fought for. I am sure that this book will help many readers, regardless of what journey they have embarked on themselves.

Tobias Winkler

Dr. Tobias Winkler is Professor of Regenerative Orthopaedics and Trauma Surgery at Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin

AT THE DESTINATION

Autumn 2021

“The man in the mirror has grown old”, I think. My beard keeps getting greyer and my wrinkles deeper. But, I still like this man in front of me. I’m really proud of him. After my morning run and shower, I’m standing in front of the mirror, ready to start the day – to start the day as a healthy person.

There’s an Indian saying: “A healthy person has many wishes. A sick person has just one.” Officially, I’m sick. I’ve been diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. But my body is fit and healthy. I’m back to being a person with many wishes.

I’m overcome with pride, as always, when I look back on recent years and my journey. I’m proud to have shown the courage to go my own way. Proud to have taken responsibility for myself and my life. Proud of my willpower, focus and discipline. Without discipline, we can’t achieve our goals.

It doesn’t matter whether our goal is to run a marathon or compete in a cycle race, to learn an instrument or prevent a heart attack, to stay fit and healthy into old age, to be there for our grandchildren, or to make the most of our new found freedom in retirement. Regardless of whether your goal is to prevent an autoimmune disease from progressing, to have a fit body as an MS sufferer or to prevent a stroke, “discipline” is always the magic word. Discipline and courage. The world belongs to the brave, to those who have the courage to do things differently.

My gaze wanders to my image in the mirror. I see a man who has shown this discipline and courage. And yes, I have been scared to death at times. But courage doesn’t mean not being scared. Courage means being scared, but doing it anyway. We need to recognise that we are in charge of our lives.

I’m almost imperceptibly nodding to myself. I’ve found my path. It’s my own, very personal path. It’s a path far away from conventional medicine, a path in harmony with my body, a path that has brought me here. Freshly showered after my run, fit, sporty, healthy and just shy of fourteen years after my diagnosis.

On the most profound level, I am convinced of this path. People have different reactions when I tell them about it – I’ve experienced everything from pure admiration and the desire to emulate it, to outright rejection. That’s okay. Because this is my journey. My body. My life.

When I see patients in my practice, who can hardly walk in early retirement, because their joints are so sore, when I see cardiac patients struggling for breath at the slightest exertion, when I see people who have literally surrendered to their autoimmune disease, I realise that all of these people have one thing in common – no perspective. These people have resigned themselves to the fact that life supposedly isn’t going to be kind to them. However, I believe that life treats all of us equally well or badly. Some of us, however, are more challenged to take responsibility for themselves. My life began to change when I started doing just that.

I’m not sure why we find it so hard to take responsibility for our lives. Maybe, because we then have to blame ourselves when things don’t go well. It seems easier to hand over the responsibility to somebody else, preferably doctors. We want medicine to fix what we ourselves have destroyed. But when we take responsibility for our life with conviction and dedication, then we can credit ourselves for our successes and these successes feel great.

I turn away from the mirror, quickly pull on some clothes and leave the bathroom, passing the door to the kids’ bedrooms, where my daughters are still asleep. If these girls only learn one thing from their dad, it’s that their life, health and happiness are in their own hands. They are not supposed to do everything the way I have done, but to do it the way they think is right. They should think independently, form their own opinions and be aware of how much their lifestyle affects their body. They should know that a diagnosis is only ever just a word and can never determine how their future will pan out.

We’ve got a name for everything: Alzheimer’s disease, bronchial asthma, atherosclerosis, coronary heart disease, high blood pressure, stroke, depression, chronic fatigue syndrome, cancer, fibromyalgia, arthrosis, rheumatoid arthritis, polymyalgia rheumatica, eczema, irritable bowel syndrome, ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, migraine, Grave’s disease, Hashimoto’s disease, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, type 1 and 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, obesity, burnout… to name just a few. All names, words, diagnoses, a sentence for many, but in my eyes often just a warning. A wake-up call to change our life, to consciously choose a healthy lifestyle, to wake up, to start doing things for ourselves, with discipline and courage.

“A healthy person has many desires. A sick person has just one” keeps running through my mind. But what if healthy people paid a little more attention to the sick person's one wish? What if we all took better care of our health? Many of the illnesses I have mentioned would never occur if we, as healthy people, dedicated ourselves to the desire for health and led a healthy life.

I go through to the living room. My wife, Laura, is sitting on the terrace, reading. My gaze wanders to the bookshelf: besides novels and travel guides, there are many books about meditation, nutrition and our genes. So much knowledge, so many eureka moments, are inconspicuously arranged on these shelves. All these books have helped me to find my own personal path, to change my diet, to recognise the influence of my genes. They all have one message in common – everybody has their life and their health in their own hands.

Laura looks up from her book: “So, what are we doing today?” I don’t know. I only know what won’t be happening: There won’t be any dizziness, or dragging one leg behind me, or poor vision in one eye. There won’t be any multiple sclerosis. In its place are new wishes and dreams. Who knows? We might end up making one of them come true today.

THE LOWEST POINT

PyeongChang Winter Olympic Games, South Korea

February 2018

I will remember the 2018 Winter Olympics in South Korea for the rest of my life. It was my fourth Olympic Games as a team doctor for the ÖSV – the Austrian Ski Association (Österreichischer Skiverband). We had to cope with temperatures of down to -30° Celsius and tried to remain in our local time zone for the entire games. This was mainly possible, because everything in the Olympic village was open 24 hours a day, so we could have our meals at the usual time. We knew all of our competitions would be taking place in the late evening local time and that our athletes wouldn't be at the peak of their performance then. We tried to make our bodies think that we were still on Central European Time and that our competitions were taking place in the morning. We didn't go to bed until four o'clock in the morning local time, slept until midday and then got up to go to our competition venues in the late afternoon or evening.

We stayed in the Olympic village. Olympic villages are like autonomous cities with everything you could imagine: Various different restaurants, their own hospital, radiology, shops. Everything. Except for the merchandise products, everything is completely free.

The Austrians had two complete houses in the village, with their flag proudly hanging on the façade. The area was vast and every building was decorated with the flags of the respective nation. Along with the official flags, the flags of each nation also hung on many of the balconies or in the windows. The Olympics always feels very special. The atmosphere, the pride about being there, is incomparable.

We had fully furnished apartments in our buildings. I was the only member of the support team, who shared an apartment with athletes. The Nordic combined athletes, Mario Seidl, Franz-Josef Rehrl, Lukas Klapfer, Bernhard Gruber and Willi Denifl, were my flatmates for these 16 days. The TV in the living room was on all day long, showing the Olympia channel that had been specially installed for the Olympic village, on which we could follow all of the competitions live. We often only returned to the Olympic village around midnight, and then went for a big dinner before returning to our apartment.

Even weeks before the games I wasn't feeling well, my leg wasn't responding properly, I couldn’t get it to do what I wanted, my left eye was worse again and dizziness was a constant companion. In general, I had been getting progressively worse since November of the previous year.

In PyeongChang, I really became aware of the state of my health. I walked into the huge dining hall in the Olympic village and my leg wouldn't do what I wanted it to. I always had to consciously lift my foot. Nothing about this leg worked automatically. When my focus was not actively on controlling this leg, I kept bending over. As soon as the distances became longer and my concentration on walking waned, the tip of my foot would bump uncontrollably into the ground. My left lower leg became tired and stiff over and over again. Despite this, I tried to go to the gym as soon as I got up – I thought I should at least be able to manage a bit of cycling. But, I felt dizzy as soon as I sat on the bike. My eyes wouldn't focus on my surroundings, I couldn't make them focus when I was moving. Then there was this artificial, diffuse light – my body wanted to escape the situation. But, my mind wanted to stay, didn't want to give up. I tried the treadmill, 10 minutes at 6 km/h. Surely, I had to manage that, actually it was nothing for me. In my prime, I had run 400 m in 48 seconds. It didn't feel like that long ago that I had contested the top spot in 400m races at the pinnacle of Austrian athletics. But, I wasn't that person anymore. I wasn't a young athlete. I was a 42-year-old medical doctor, who had been suffering from multiple sclerosis for ten years.

So now, for a short jogging session on the treadmill. Surely that had to be possible! The 10 minutes were indescribably long. I saw it through, I proved to myself I could do it, but it didn't feel like a triumph. When I stepped off the treadmill, I could hardly stand. My left lower leg kept tipping away, wobbling about and shooting uncontrollably forward. It was a horrible feeling. I had completely lost control over my left leg.

I tried to cover it up and sat on the floor and stretched and stretched and stretched. After 15 minutes, I tried to stand up again. My leg obeyed again and I slowly began to walk normally.

We were usually at the ski jump until late evening. I did lots of short walks during training sessions and competition. My leg only obeyed if I really put in the greatest effort. I felt dizzy and staggered with every step. I was also unable to remember even the simplest routes, never found my way to meeting points, had problems keeping appointments and I was a thousand kilometres from home and completely disorientated. I had to put utmost effort and concentration into every single step, so it would have been helpful if I had known the shortest route to my destination. Nothing happened naturally; I had to consciously control all of the usually subconscious processes that take place between brain and leg.

REST!

It was the first rest day. As the name suggests, I should have used it for resting. The other team members asked if I would like to go cross-country skiing with them. They knew that I, the ambitious team doctor, always tried to keep up with the athletes, that I loved skiing and cross-country skiing. They noticed my hesitation.

“Come on, it's practically a walk. It’ll be quite slow. Don't worry, you'll easily keep up”, Christoph Bieler persuaded me.

How could I refuse? I could hardly admit to myself how I felt. And apart from that, this was my chance to prove to myself that things weren't that bad. I couldn't cycle, running was impossible and walking was difficult – but if I could manage cross-country skiing, it would at least be a glimmer of hope!

So, we went to the cross-country skiing arena together. After passing the security checks in the special security tent, we entered the huge area that was divided into the competition area and a training area. Cross-country skiers, biathletes and Nordic combined athletes from 91 nations had their changing and waxing containers here, which were normal building containers, converted for this purpose. There were also the containers of the individual outfitters and various food tents. The containers were all lined up together and all looked the same. It was a nightmare for people like me who didn't have any sense of direction.

The service people gave me skis and I followed the others to the entry point of the training track. Even as I walked, I knew that I would regret this decision. The ground was uneven and icy. I had to concentrate on every step and the images before my eyes blurred. The fear of being exposed, of being noticed, of having to admit I was physically no longer capable of doing anything, visibly deteriorated my condition. I felt like I couldn't move my left eye, as if both my eyes were looking in different directions. Everything was blurring and I felt increasingly dizzy. It was clear from the start that top athletes ski fast, even if they said they would go slowly. I had known these people for years and I knew that they never skied slowly, but I also knew that, in recent years, I had always been able to keep up with what they considered to be slow. Ignoring all my body's warning signs, I stood with the athletes and support team members (who were also former athletes) at the entry point to the course, clipped on my skis and we all set off together. It didn't take five minutes for my body to defeat my willpower. I was more than thirty meters behind and I could hardly stay up on my skis. I was getting angry. The group in front of me had met one of their biathlete friends. He dropped back to say “hi” to me as well and we started a bit of small talk. I was concentrating on putting one foot in front of the other and was absolutely unable to exchange even a word with him. Then we had a short downhill section, then a compression and I literally ended up on the ground. The others kept going, because that's how it is with athletes, once you fall over, you get up again. It's no big deal. But, this time, it was different. A baffled look from the biathlete next to me and shouts from the group in front

"Come on, we’re waiting for you", called Lukas Klapfer.

“No, no. I'll ski by myself; you carry on without me. We'll meet back at the container afterwards", I replied.

Laboriously, I made my way to the entry point, and when I got there, it took me more than an hour to find the right container. It was an awful situation, I was completely helpless. I was trapped in a maze of containers. One container next to the other, with small, sneaky paths leading in all directions. Barriers and uneven ground also got in my way. I couldn’t remember where I was supposed to go. I didn't know where our container was. Disoriented, I staggered around between the containers, desperately searching for an Austrian flag. Like in the Olympic village, almost every container in the cross-country arena was decorated with the flag of the respective nation. The worst thing was knowing that I only had to find a short, simple path, but I also knew that I couldn't find my way around due to my condition. I felt like I kept walking in circles. I didn't know where I was, or what direction I was supposed to take.

Despair began to well up inside me. How would everything go from here? What would my future look like? What kind of life would it be if I continued to progress like this?

When I finally found the right container, I met my cross-country skiing group again. They had been skiing for an hour in the meantime.

"And? Where have you been all this time?", asked Christoph Bieler.

"I was skiing too, very slowly, at my own pace, just for me. It was great", I lied.

The truth was unutterable at that point. I was at my wits’ end, dizzy, my eyes were moving strangely and I no longer had any control over my left leg.

Back at the accommodation, I told my good friend and colleague, Jürgen, for the first time what had just happened to me. Jürgen lived on the floor above our apartment with other members of the ski jumpers’ support team and I visited him in his room after our cross-country ski trip.

“It’s so depressing, my leg just won't do what I want it to. I can't control it; it just does its own thing all the time. I just can't lift my foot properly; I have to concentrate with every step, or my toes just tuck in when I walk. I also feel dizzy, especially when I'm standing. It's horrible."

HOW ARE YOU?

On February 24th 2018, Willi Denifl, Bernhard Gruber, Lukas Klapfer and Mario Seidl won the bronze medal in the Nordic combined team event This was an incredible achievement for us as a team that only very great optimists had expected. We had managed to beat big nations like Japan, Finland and France. The athletes were duly celebrated in the Austrian building. Days like this are the highlights in an athlete's life. But, medal events and moments when great victories were celebrated, were also the days I found the hardest. The victorious athletes entered the Austrian building, and in their honour, the lights were dimmed, so that the athletes would shine in all their glory when it was switched back on. The moment the lights were on again, everybody applauded and the room was flooded with a bright neon light. I could no longer concentrate. Everything blurred. I tried to focus on the people around me, to stop the dizziness and to pretend that everything was okay. There was loud music and the babble of voices. My good friend, Toni Innauer, who I hadn't seen for ages, was standing next to me.

“Stefan, it's been a while. How are you?”

I could hardly speak, everything around me was blur and all I could do was concentrate on not letting it show.

Shortly afterwards, I was standing together at a table with Jürgen and our Olympic chaplain, Jörg.

The same question came again: “Stefan, how are you?” The question is really just a cliché for most people and doesn't show any genuine interest. But, with Jörg, I could sense the serious interest and the honesty of his question. That was when the truth literally burst out of me.

“Pretty shit to be perfectly honest”, I confessed. "I've had MS for ten years and I've gone drastically downhill in the past few months”, I admitted openly for the first time.

"Should I pray for you?", he offered.

Part of me longed for a supernatural power that would get my life back on track, and I agreed. "Should we pray here together?"