Table of Contents

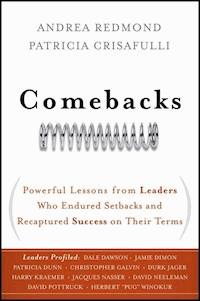

Title Page

Copyright Page

Dedication

Introduction

Chapter One - DAVID NEELEMAN WHEN IT’S TIME TO MOVE ON

Growing Up in Brazil

Entering the Travel Business

At the Controls of JetBlue

Neeleman’s Servant Leadership

An Ice Storm to Remember

Working Through It

Taking Off in Brazil

Chapter Two - DAVID POTTRUCK A PORTRAIT IN CANDOR

Big Dreams and a Bright Beginning

Welcome to the Business World

The Game Changes

Bouncing Back

Chapter Three - PATRICIA DUNN TRIAL BY FIRE

Joining the HP Board

Embattled on Two Fronts

The Accountability Conundrum

Lessons Learned

Chapter Four - CHRISTOPHER GALVIN THE POWER OF RESILIENCE

Facing the Business Battles

A Lame Duck CEO

The Worst Six Months of His Life

Starting Over

The Importance of Resilience

“Gut It Out” and Other Lessons Learned

Chapter Five - HERBERT “PUG” WINOKUR AFTER THE STORM

Connections and Opportunities

The Enron Board

The Harvard Connection

Enron Becomes ‘Unreal’

The Harvard Board Takes Action

Lingering Questions

After the Storm

New Ventures and Unfinished Business

Chapter Six - HARRY M. JANSEN KRAEMER, JR. VALUES-BASED LEADERSHIP

The Balanced Life

Leadership in Action

When Results Disappoint

Departures and Life Lessons

New Beginnings

Sharing Life Lessons

Beware the Speeding Porsche

Chapter Seven - JACQUES “JAC” NASSER NEW LIFE AFTER A LONG CAREER

Going to Work for Ford

At Ford Headquarters

Assessing a Life at Ford

Deciding What Not to Do

A New Role

Chapter Eight - DURK JAGER PEACE OF MIND AND WALKING AWAY

Joining P&G

A Quick Exit

Lessons from P&G

Chapter Nine - JAMIE DIMON THE ULTIMATE COMEBACK

Focused on Success

A Financial Empire Is Created

The Citigroup Deal

The Firing of Jamie Dimon

Trying on Opportunities

Joining Bank One

Back to New York

Chapter Ten - DALE DAWSON PURSUING A LIFE OF PASSION

Getting Up Before Everyone Else

In Pursuit of Passion

Purpose for the Second Half of Life

No Regrets

Notes

Acknowledgements

About the Authors

Index

Andrea Redmond

Patricia Crisafulli

Copyright © 2010 by Andrea Redmond and Patricia Crisafulli. All rights reserved.

Published by Jossey-Bass A Wiley Imprint 989 Market Street, San Francisco, CA 94103-1741—www.josseybass.com

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400, fax 978-646-8600, or on the Web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, 201-748-6011, fax 201-748-6008, or online at www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

Readers should be aware that Internet Web sites offered as citations and/or sources for further information may have changed or disappeared between the time this was written and when it is read.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor author shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

Jossey-Bass books and products are available through most bookstores. To contact Jossey-Bass directly call our Customer Care Department within the U.S. at 800-956-7739, outside the U.S. at 317-572-3986, or fax 317-572-4002.

Jossey-Bass also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Redmond, Andrea.

Comebacks : powerful lessons from leaders who endured setbacks and recaptured success on their terms / Andrea Redmond, Patricia Crisafulli. p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

eISBN : 978-0-470-61988-9

1. Chief executive officers—Case studies. 2. Leaders—Case studies. 3. Success in business—Case studies. I. Crisafulli, Patricia. II. Title.

HD38.2.R435 2010

658.4’2—dc22

2010004757

HB Printing

With love and gratitude:

For Bill and Duke —A. R. For Joe and Pat —P. C.

Introduction:

When the Rug Gets Pulled

At some point in life, the rug gets pulled from under us. We get fired. A long-awaited promotion does not materialize. A business fails. Our health suffers. A relationship—in business or in our personal lives—ends. No one is immune. Regardless of job title or level of achievement, an upset of some type is inevitable.

For most people, a professional setback such as getting fired is a private matter. Dealing with the aftermath, from the emotional upheaval of being rejected to the career uncertainty, happens behind closed doors. For high-profile leaders, however, circumstances are much different. In addition to dealing with the intensely private issues that go along with a career upset, the events surrounding their setbacks are often played out very publicly. Suddenly every detail becomes fodder for media commentary and analysis. Previous successes and failures are chronicled in news stories (often with inaccuracies), and unflattering pictures are splashed everywhere. Private upset becomes public embarrassment.

This fact became clear to Andrea seven years ago, when she sat down with Jim Cantalupo, a long-time McDonald’s Corporation executive and then CEO of the company, to discuss leadership traits for a book project in which she was involved. In the two-hour conversation that followed, Jim and Andrea established an instant rapport and their discussion deepened. As Jim reflected on his life and career, he shared what it had been like for him a few years prior when he lost out on the CEO role at McDonald’s and left the company feeling defeated and dejected. He had been within a millimeter of becoming CEO, only to lose the job he wanted—and his family and friends heard the news on television and read about it in the newspaper. Later, Jim was asked to return to the company and was brought in as CEO.

A short time after this conversation, Jim Cantalupo died suddenly. The story he shared stayed with Andrea for years. She began reaching out to CEOs who were terminated, offering a word of encouragement or to be a sounding board. When Andrea met Tricia, who at the time was writing The House of Dimon, a leadership profile of JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon and the ultimate comeback story, they realized that there was a deep story to tell about what happens when leaders go through setbacks and their process to recapture success on their terms.

In Comebacks, we share the stories of ten high-profile leaders who experienced a serious upset in one form or another—such as being fired or asked to resign, quite possibly due to circumstances that were at least partially beyond their control. Often the termination happened suddenly and unexpectedly. Many said they did not see it coming, describing their termination in words such as being “blindsided” and “sucker-punched.”

Being fired as the leader of a large firm often triggers a media blitz that most of us will never face. And the obvious should be stated: A CEO who is fired does not have the same financial worries (if any at all) as the rest of us who lose a job. However, we all know what it’s like to feel embarrassed and vulnerable, and to be caught up in self-doubt and second-guessing. Based on these commonalities, there may be much to learn from the experiences of these CEOs and other leaders who managed to maintain a sense of self in the midst of great turmoil: how they picked themselves up, redefined their priorities, took accountability and responsibility where appropriate, and created and explored new possibilities and directions.

As we discovered, sometimes those lessons came in the form of twenty-twenty hindsight, as people saw and acknowledged what they could or should have been done differently. Other times, the lessons involved strategies for coping, such as resilience, self-knowledge, and relying on family, friends, and other close supporters. Having endured a setback, they learned or affirmed that their identities are not the same as their job titles; that a balanced life must constitute more than just a job. The lessons were as varied as the individuals themselves.

Equally interesting were the leaders’ second acts. Each person’s choices were unique and fitting to his or her circumstances, personality, preferences, and stage in life. Regardless of how one bounced back, success for each person was defined on his or her terms. Whether a person decided to pursue another leadership position or went off in an entirely different direction, essential to taking the next step were evaluation of one’s goals and priorities and an appreciation of what matters most. Only then could they clearly weigh the opportunities in front of them. Collectively, the stories in Comebacks show that there is no one way or right way to endure a setback. The way forward is a course that people must chart for themselves.

Patricia Dunn’s strategy for facing felony charges related to the corporate spying scandal at Hewlett-Packard while she battled cancer was to make a “cosmic distinction between those I knew and didn’t know. . . . ” To endure difficult days of being vilified in the press, she relied on the support of family, friends, current and former colleagues, and others who reached out to her. “If the world had gone silent,” she said, “I would have been devastated.”

For Christopher Galvin, being asked to step down as CEO of Motorola, the company founded by his grandfather, just as a turnaround he had put in place was coming to fruition, was deeply painful. To endure the setback he relied upon inner resources of resilience that allowed him to “gut it out.” As he observed, “Nobody can talk you out of what you are feeling. People say all kinds of nice things, but that doesn’t take away the pain.”

Following a setback, most of the leaders we interviewed advocated taking a break, physically and mentally, in order to avoid making a rash career decision. Jamie Dimon, now CEO of JPMorgan Chase, explained that after being fired as president of Citigroup in November 1998 he engaged in “a thought process” to figure out his next step. “What did I want to do? I didn’t want to fill up my calendar before I decided what I wanted. I wanted to decide,” he said.

Others bridged the transition differently. David Neeleman responded to the upset of leaving JetBlue Airways, which he had founded, by focusing on what he could do next. Even as he continued to process the emotional upheaval of leaving behind the company that was his “baby,” Neeleman launched his next venture. As a servant leader dedicated to helping others, Neeleman found it was better to “find something else to focus on. . . . Think about people other than yourself.”

Focusing on others also helped Dale Dawson decide what to do in the second half of his life when, after selling his business, he suddenly lost the passion that had always spurred him ahead. His response was to employ his business skills as an executive and investment banker in a completely new arena—a place in the world where there is deep need and great potential. His story stands as a dramatic example of being willing to rethink one’s life and career and to redefine success. “Are you being led where you need to go?” Dawson observed. “If not, don’t be afraid to walk away.”

In the midst of a career disappointment, a common experience is to return to one’s roots. After stepping down as CEO of Ford Motor Company, Jac Nasser took several months off to return to Australia where he had been raised and where his ninety-eight-year-old father still lives. He also became grounded in the many lessons his father had taught him by word and example over the years. Nasser credited his father for having an “unwavering level of confidence and a belief that things will work out in the long term if you work at them.”

Harry Kraemer, after resigning from Baxter International, relied upon his lifelong practice of self-reflection, which he adopted in high school and which is the cornerstone of his leadership today. Through self-reflection, Kraemer was able to look at his life honestly and with new perspective as he weighed his choices of what to do next. “You have to take some time to really stop and think through what you are all about,” Kraemer explained.

David Pottruck, who left as CEO of Charles Schwab & Company where he had worked for twenty years, has also engaged in an honest and candid self-assessment of his strengths and accomplishments—as well as his shortcomings and failures. A former college athlete who distinguished himself in football and wrestling, Pottruck had endured disappointments before in his life, but always managed to move on to new successes. As he observed, “There are always setbacks. Success in life demands the ability to bounce back.”

Each of the executives who navigated through career storms was challenged to reassess his or her goals, beliefs, character, and sense of self. For Herbert “Pug” Winokur, being a long-time outside director on the board of Enron Corp. put him in the crosshairs of scrutiny when the firm imploded in the midst of allegations of fraud. Through years of testimony, from Congress to creditor panels, Winokur was sustained by the knowledge that he and other outside board members had acted in good faith based upon the information that was presented to them by company management. Therefore, he was able to separate what was happening around him from what was happening to him. “You have to accept that it’s not about you at all,” Winokur observed.

In the midst of a setback, it is tempting to sink into feelings of self-doubt and or even defeat, believing that every previous accomplishment has been negated. Not true. A career is not a single episode. An array of experiences, both positive and negative, comprises all that a person has accomplished. Durk Jager, former CEO of Procter & Gamble, worked for the company for thirty years, including several years in top leadership positions. Although he had to step down as CEO, Jager’s assessment of his career is summed up in a powerful statement: “I have done my best.”

The leaders profiled in Comebacks generously contributed their stories, describing details of their lives and careers, which led ultimately to reaching a pinnacle of achievement. They also recounted not only what happened when the rug was pulled from under them, but also how they felt at the time, and what they needed to do in order to move forward again. Their stories are related in Comebacks without judgment and are told primarily from the viewpoint of the corporate leader. Our intention is to give you a view through that leader’s eyes, to understand what it was like to be on top of one’s game one minute and then sidelined the next. For some of those profiled, this is the first time that they have spoken at such length and depth about their experiences from setback to comeback. Without the candor of those we profiled, Comebacks never would have been possible. We salute them for sharing their stories and their wisdom, and we applaud their willingness to demonstrate courage and vulnerability in order to share their lessons with the rest of us.

I don’t think the American dream is to start a company and sell it. Sometimes you end up selling your dream. There are things that money can’t buy.

—DAVID NEELEMAN, FOUNDER AND FORMER CEO OF JETBLUE AIRWAYS CORP., FOUNDER OF AZUL LINHAS AÉREAS BRASILEIRAS

Chapter One

DAVID NEELEMAN WHEN IT’S TIME TO MOVE ON

Every time David Neeleman has faced a career upset or disappointment, he has quickly responded by pursuing the next opportunity. His phoenix-like determination to rise from the proverbial ashes has led Neeleman, now fifty, to establish no less than three airlines thus far. His entrepreneurial drive has been fueled by a creative vision to establish organizations that are as good as, or even better than, their competitors, and in the process to help other people.

“From the time I sold my first company when I was thirty-three, it has always been about creating new things and helping people reach their potential. Money is a way to keep score at times I suppose, but it doesn’t bring happiness. Money is the means, but it’s not the be-all and end-all,” Neeleman said.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!