20,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

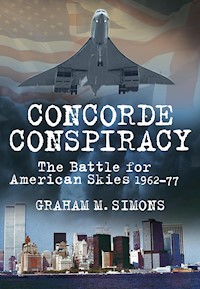

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

An innovation in aviation development, Concorde was the subject of political rivalry, deceit and treachery from its very inception. After their failure to be the first nation to develop a jet airliner for transatlantic flight or to send spacecraft into space, the US Government was adamant that they would beat other nations to the goal of supersonic flight and so development of the SST began. However, with McNamara and Shurcliff's negative attitudes to the project, it was soon killed off. Thus began the 'if we cannot do it, neither can you' attitude towards other countries' efforts for supersonic flight. This is the story of ten years of behind-the-scenes political intrigue, making use of inside information from two American presidents and the Federal Aviation Authority, as well as recently declassified papers from the CIA and President Kennedy on how the Americans planned to destroy Concorde and their own American SST. Lavishly illustrated with black and white and colour images throughout, Concorde Conspiracy is a must read for any enthusiast on supersonic flight and anyone who enjoys a real-life conspiracy.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

Contents

Title Page

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1 In the Beginning

2 ‘First in the World in Air Transportation’

3 Mack the Knife

4 Pressure to Cancel – and a Pause?

5 A Change of Tactics

6 Wiggs, Nixon, Shurcliff and S/S/T and Sonic Boom Handbook

7 Certification

8 The Coleman Hearing

9 The Battle of New York

10 Epilogue

Bibliography/Research Sources

Plate Section

Copyright

Acknowledgements

A project of this nature could not be undertaken without considerable help from many organisations and individuals. Special thanks must go to Marilyn Phipps of Boeing Archives, Col Richard L. Upstromm and Tom Brewer from the USAF Museum, now the National Museum of the USAF, for the provision of many photographs and details. The archives of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics provided access to all their relevant material, as did Lynn Gamma and all in the US Air Force Historical Research Center at Maxwell Air Force Base, Montgomery, Alabama. Much other primary source documentation is also located in the National Archives and Records Administration at College Park, Maryland, the history files of the Central Intelligence Agency and the Presidential Libraries of John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. Thanks must also go to Darryl Cott of British Aerospace, David Lee, the former Deputy Director and Curator of Aircraft at the Imperial War Museum at Duxford, John Hamlin and Vince Hemmings, the former curator of the East Anglian Aviation Society’s Tower Museum at Bassingbourn.

The author is indebted to many people and organisations for providing photographs for this book, many of which are in the public domain. In some cases it has not been possible to identify the original photographer so credits are given in the appropriate places to the immediate supplier. If any of the pictures have not been correctly credited, the author apologises.

Introduction

The story of Concorde and the Americans is one of spies, lies, arrogance, dirty tricks and presidential hatred. It is one of deceit, treachery, mistrust and confusion.

The Americans were initially dismissive of Anglo-French efforts – then arrogant to the point that they thought that not only could they do better, but that they were the only ones capable of completing the project. President Kennedy said, ‘Make it happen – make it bigger, make it faster.’ He might well have added, ‘Make it to beat my presidential rival in France.’

The Americans always referred to the aircraft as ‘the’ Concorde – the Europeans called it simply ‘Concorde’, although there were initially spelling differences with or without the ‘e’.

It is often said that knowledge is power, so the Americans set out to gain knowledge on their competitors – by fair means or foul. They had been comprehensively beaten to the title of being the builders of the world’s first jet airliner by the British de Havilland Comet – an aircraft that then went on to beat them to the title of the world’s first jet airliner to enter airline service, and the world’s first passenger jet to fly on the prestigious transatlantic service. Even the Soviets managed to get their Tu-104 into regular airline service two years before the Boeing 707. Militarily they had also been comprehensively beaten into space, with the first satellite, the first animal and the first man and woman placed into orbit.

For a nation that regarded itself as the world’s only superpower and to be technologically more advanced than any other nation, the Americans were determined that they would not be beaten to the next milestone: the builders of the world’s first supersonic airliner. The Central Intelligence Agency, the Federal Aviation Authority and other government agencies all came in to play under Presidential Order to spy on the French, the Soviets and the British in order to gain an edge.

Jingoism, blind patriotism and national pride also played their part; but this eventually degenerated into political infighting amongst vested-interest groups. With the assassination of President Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson took over and, as with his predecessor, was very much in favour of an American supersonic transport aircraft (SST) project. Under Presidential Order, he established a President’s Advisory Committee on Supersonic Transport (PAC-SST) under the chairmanship of Robert Strange McNamara, the US Secretary of Defense.

By definition, the chairman of any committee is selected to preside over meetings and lead a committee to consensus from the disparate points of view of its members. The chairman is expected to be impartial, fair, a good listener and a good communicator. Nothing could be further from the truth with Robert McNamara. He set out to cold-bloodedly sabotage the project right from the start. In his own words:

Right at the beginning I thought the project was not justified, because you couldn’t fly a large enough payload over a long enough nonstop distance at a low enough cost to make it pay. I’m not an aeronautical engineer or a technical expert or an airline specialist or an aircraft manufacturer but I knew that I could make the calculation on the back of an envelope.

So I approached the SST with that bias. President Johnson was in favor of it. As chairman of the committee I was very skeptical from the beginning. The question, in a sense, was how to kill it. I conceived an approach that said: maybe you’re right, maybe there is a commercial market, maybe what we should do is to take it with government funds up to the point where the manufacturers and the airlines can determine the economic viability of the aircraft. We’ll draw up a program on that basis.

So the project studies continued, but the steady drip, drip, drip of McNamara’s negative attitudes and biased reporting slowly defeated any hopes of an American SST, just as he had killed off the North American B-70 Mach 3 bomber project for the United States Air Force (USAF) and through manipulation of funding with the World Bank also ensured the death of the UK TSR-2 strike aircraft in favour of the US General Dynamics F-111 Aardvark.

McNamara had a track record for political intrigue and manipulation. He may have come to the post of Secretary of Defense from the Ford Motor Corporation, but he moved in the murky world of Cold War spies, so-called ‘Black’ projects and those who worked on them. This was a highly secret and insular world that had links between the politicians on Capitol Hill, the defence industry and the rarefied atmosphere of research faculties of the Ivy League universities. From this world came the strange saga of Professor William A. Shurcliff’s Citizens’ League Against the Sonic Boom, which suddenly surfaced just at the time Robert McNamara left public office and went to head the World Bank. Shurcliff, who had worked on the fringes of the atom bomb project, was employed by Polaroid Corporation under Edwin Land of Land Camera fame, who also secretly worked for the Defense Department and the CIA on the cameras for the U-2 and SR-71 spyplanes. Shurcliff was well known in this world and was thus in a good position to express publicly the negative views on the SST held by McNamara. It is doubtful if we will ever know the depth and scope of these links, for apart from much still remaining secret, when Land died on 1 March 1991 at the age of 81, his personal assistant shredded his personal papers and notes.

Shurcliff’s Citizens League Against the Sonic Boom was without doubt instrumental in killing off the Boeing 2707, so that hurt American pride and the arrogance of their national ego easily created a mindset of ‘if we cannot do it, neither will you’. This collective mindset then set about destroying the Anglo-French Concorde by attempting to block the aircraft’s certification to operate into and over the USA and prevent its access to American airports by legal challenges and bans.

This then is that story – a story told using primary source documentation. It is one that has echoes back to the de Havilland Comet and Boeing 707, and resonates forward to today with the recent political battle between Boeing and the European Aeronautic Defence and Space Company over the KC-X replacement for the ageing Eisenhower-generation fleet of KC-135 tankers that were so badly needed for the USAF. This was a battle that was won by Boeing by using partisan political support such as that which came from Senator Patty Murray, who is just the latest in a long line of politicians from Capitol Hill who were prepared to manipulate the facts in favour of ‘the company’ rather than concentrate on what was really going on.

Graham M. Simons

Peterborough

June 2011

1

In the Beginning

From the late 1940s onwards, it seemed that man’s mission was to achieve even greater speed, and this was translated first into subsonic jet aircraft and then into supersonic military aircraft development, with the first major British design being the Miles M.52 – an aircraft design that was well ahead of its nearest rival, the American Bell X-1. According to Miles Aircraft’s chief aerodynamicist Dennis Bancroft, in 1944 the Air Ministry signed an agreement with the USA to exchange high-speed research and data. Miles gave their data to Bell Aircraft, but the Americans reneged on the arrangement and no data was forthcoming in return. The M.52 was cancelled in February 1946. The transition to a supersonic commercial transport was to take much longer.

Having led the way with commercial jet transports, it was natural that in order to capitalise on this initial success, Britain’s aeronautical design teams should turn their attention to supersonic transport aircraft. By the mid-fifties, the ground lost by the de Havilland DH.106 Comet accidents and Vickers VC-7 cancellation could, it was hoped, be reclaimed with the production of hundreds of aircraft travelling faster than the speed of sound.

Great Britain was not, however, the only country studying supersonic transports; so were the French, the Americans and the Soviets. One design – due to tremendous political infighting – was eventually stillborn; another, although the first to fly, soon gave up; and the two remaining merged into one to carry passengers routinely very quickly and very expensively carry passengers across the Atlantic. That survivor, so scorned by economists, acclaimed by engineers and loathed by environmentalists, was the Anglo-French Concorde.

The British Miles M.52 design that could well have been the world’s first supersonic aircraft to fly. Seen here is the mock-up at the Miles Woodley site in 1944. (Simon Peters Collection)

Charles E. ‘Chuck’ Yeager with his Bell X-1 46-062, ‘Glamorous Glennis’, in which he became the first man in the first aircraft to break the sound barrier officially, on 14 October 1947. (USAF)

For any nation to create a supersonic airliner was, and still is, an enormous challenge. Scientists had explored the secrets of aerodynamics during the first half of the twentieth century, translating the theory and experimentation into the design and refinement of a succession of aircraft. Air transport had seen progressive increases in speed, but strange effects appeared when aircraft approached the speed of sound. Air resistance rose dramatically to impose a serious obstacle – the so-called sound barrier – to conventional flight. The changes were sudden as the normally orderly airflow broke down and shock waves, akin to the bow waves of a ship, were generated at the nose and tail of the aircraft.

In 1947, USAF captain Charles E. ‘Chuck’ Yeager, flying the rocket-powered, air-launched Bell XS-1 research aircraft that bore more than a passing resemblance to the M.52, including the one-piece tailplane, became the first pilot to exceed the speed of sound in level flight. Supersonic speeds, it should be explained, are expressed in terms of Mach number, generally pronounced ‘Mak’, which is the speed of an object moving through air, or any other fluid substance, divided by the speed of sound in that substance for its particular physical conditions, including those of temperature and pressure. It is commonly used to represent the speed of an object when it is travelling close to or above the speed of sound. Mach l varies from about 760mph at sea level to about 660mph at a height of 50,000 to 60,000ft, and gets its name from Austrian physicist and philosopher Ernst Mach (1838–1916), who contributed much to its study. By the end of the 1950s a number of fighter aircraft were in service that could fly brief bursts at supersonic speeds, but they could not cruise supersonically for hours at a time.

The Work of Barnes Wallis

Even before the end of the Second World War, Barnes Wallis recognised that the next big milestone in flight would be a supersonic aircraft, and his main interest became the development of a supersonic airliner. He recognised that the increase in drag at supersonic speeds would require very efficient aerodynamics, and as a leap towards this target – and to reduce weight – Wallis proposed to dispense entirely with the tail for his new aircraft. He also wanted to exploit the idea of laminar flow to produce a fuselage with very low skin drag. The basic form of his new aircraft, which he called an aerodyne, thus had just three structural elements: an egg-shaped fuselage and two wings which had no flaps or ailerons. Although offering efficient flight characteristics, this new form of aircraft presented substantial control problems. To solve these, Wallis used his knowledge as an airship designer. He knew that when an elongated solid body such as an airship or aircraft fuselage travelled through the air at a slight angle, it generated large rotational forces but no substantial linear forces. To balance these rotational forces, Wallis planned to locate the wings towards the rear of the aircraft, giving an inherently stable form. Control was to be effected by pivoting the wings round a vertical axis – sweeping the wings backwards would allow faster speeds, while sweeping them forwards would give greater lift for landing and take-off. To change direction, he proposed to sweep the wings unevenly, the aircraft turning towards the wing that was swept the most. This was the ‘wing-controlled aerodyne’.

Sir Barnes Neville Wallis CBE, FRS, RDI, FRAeS (b. 26 September 1887, d. 30 October 1979) with one of his Swallow models. Note the engines above and below the wing. (Vickers)

Wallis developed a series of models under the designation ‘Wild Goose’, but as the Wild Goose experiments continued, he realised that he was not going to get the range required from the design. By 1953, the ‘slender delta’ planform was the favourite of designers of supersonic aircraft, and he knew that most of the lift from this shape came from the leading edge. He therefore proposed an arrowhead planform using a delta, but with the non-lifting rear part removed, and with the wings projecting backward from a smaller delta-shaped forebody which also provided lift. Having the wings so far back would make take-off and landing problematic, so he reverted to his variable-geometry wing concept, pivoting the wings at the rear of the forebody, so that they could be swept forward – almost straight – for low-speed manoeuvring and landing. This series of designs became termed ‘Swallow’.

An SST variant was proposed long before the Concorde project, with the swing wings having the benefit of reducing landing and take-off speeds, foreshadowing the Boeing 733/2707 of more than a decade later. A unique feature of both versions of the Swallow was the ‘elevator cockpit’. The entire flight deck, contained in a circular tub, could be raised above the fuselage to increase vision and lowered to improve aerodynamic streamlining.

By 1960, Wallis realised that Mach 2.5 – which at the time was regarded as the speed limit on the slender delta – was too slow and he produced a new design for an aircraft with a top speed of Mach 4–5.

Barnes Wallis with another version of the Swallow, showing the ‘elevator cockpit’ that could be raised to improve the view over the nose.

A possible layout for the civil version of the Swallow. (Vickers)

Contemporary designers exploring speeds in this range were being challenged by the material problems associated with the heat generated by the air friction. Solutions to these used materials like stainless steel and titanium for the airframe. However, Wallis was keen to continue using light alloys, but devised an ‘isothermal flight’ profile which balanced increasing speed with increasing height, and therefore thinner air, allowing the airframe temperature to remain within safe limits. Wallis’ experimentation with new forms continued, using one single wing that was still pivoted on a horizontal shaft with large leading- and trailing-edge flaps. This allowed the configuration of the aircraft to be continually altered for the wide range of different flight regimes encountered between take-off and a cruise at above 100,000ft and Mach 4. As the aircraft was in the most efficient configuration at all times, range could be maximised, and a nonstop London–Sydney flight was believed to be achievable with this ‘universal’ aircraft, with a flight time stated at being around five hours.

A model of the Barnes Wallis Swallow IV with swing wings and a rear fuselage that is split in two directions – one across to give the effect of elevator control, and one down the rear fuselage to provide aileron control. (Author)

Enter the Royal Aircraft Establishment

There were serious aerodynamic problems that had to be solved in the design of a supersonic airliner, and not only in shaping the aircraft to give the best possible performance. The study of supersonic airliners in Britain really began in 1954 at the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) at Farnborough, when a working party was set up under noted Welsh aeronautical engineer Morien Morgan, who was later called ‘the father of Concorde’, to investigate the possibility of a faster-than-sound transatlantic airliner. Its initial design was for an aircraft based around the Avro 730 supersonic bomber, with thin unswept wings and a long slender fuselage, only able to accommodate around fifteen passengers. The aircraft could have travelled at Mach 2 from London to New York, but the all-up weight was estimated at above 300,000lb, with an excessive cost per passenger. It was evident that the development of such an aircraft was not justifiable.

All this changed after the head of supersonic research at the RAE, Philip Hufton, went to America in 1955, and saw developments in supersonic aircraft using the ‘area rule’ effect. This stated that if the shape of an aircraft’s cross-sectional area was the same all along its length, the wave drag would be minimised. Encouraged by this, Hufton filed a report suggesting that a supersonic transport may now be feasible. A further avenue of investigation was an entirely new shape of aircraft based on German wartime research which could be designed for supersonic flight – the delta wing.

As a result of this, those back at Farnborough, who just months before had been saying that an SST could not be justified, now had their interest rekindled in a major way. Among those now re-examining supersonic flight at the RAE was a German aerodynamicist, Dr Dietrich Küchemann CBE, FRS, RAeS. Before the war Küchemann joined Ludwig Prandtl in aerodynamics research, publishing his doctoral thesis in 1936. With the war looming, Küchemann volunteered for service in 1938, and as expected was given a non-combatant role in Signals, serving from 1942–45. During this period he continued to research, notably into the problems of high-speed flight, wave drag, swept-wing theory and initial steps on the road to the ‘area rule’, and designed an aircraft called the ‘Küchemann Coke Bottle’. After the war he moved to England as part of Operation Surgeon, a British programme to exploit German aeronautical research and deny German technical skills to the Soviets. Küchemann joined the RAE at Farnborough where he studied aircraft propulsion in depth and became the leading expert on such topics as ducted fans and jet engines. He also began to study delta designs. In order to further research, it was decided that the RAE alone could not look into all the problems that would need to be investigated, especially if Britain was to try to get ahead of the field as it had done with the Comet less than a decade earlier. It was decided that all the major parties in the industry, as well as airlines, government, ministries and the Air Registration Board, should be included.

Welsh aeronautical engineer Sir Morien Bedford Morgan CB (b. 20 December 1912, d. 4 April 1978)

Under the chairmanship of Morien Morgan, the deputy head of the RAE, the Supersonic Transport Aircraft Committee (STAC) was set up on 1 October 1956. This committee had its first meeting on 30 November 1956. Its two key objectives were to investigate the possible market for an SST and to define an operator’s broad requirements so that areas of desirable research could be carried out. Among the representatives were all the major aircraft companies, namely A.V. Roe, Armstrong Whitworth, Bristol Aircraft, de Havilland, Handley Page, Shorts and Vickers-Armstrong. These were joined in November 1957 by English Electric and Fairey. Also represented were the four main engine companies: Armstrong Siddeley, Bristol, de Havilland Engines and, of course, Rolls-Royce. Other representatives came from the British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) and British European Airways (BEA), as well as government departments: the Air Registration Board, the Aircraft Research Association, the National Physical Laboratory, the National Gas Turbine Establishment, RAE, Ministry of Supply and Ministry of Transport and Civil Aviation. The committee foresaw the prestige that a successful SST would bring to Britain, as well as the possible military transport spin-off.

The committee looked at the problems of flying at speeds from Mach 1.2 to Mach 2.6, and the issues that were associated with materials, especially at a higher speed, with detailed research carried out. In the event, two sizes of aircraft were proposed: a medium-range transport carrying 100 passengers over 1,500 miles at Mach 1.2 (800mph) and a Mach 1.8 (l,200mph) or faster long-range airliner carrying 150 passengers. Many different shapes of aircraft were investigated, including swept wings, variable wings, M-wings, slender wings and aircraft capable of vertical take-off. As a result of the research, the committee found that although a Mach 2.6 machine would probably be feasible, its development would take too long.

At the time Morien Morgan commented:

Light alloy construction would be used, and engines could be straightforward developments of present-day large jet units. Long slender shapes, with subsonic leading edges and supersonic trailing edges, can give sufficiently high L/D while the optimum cruise aspect ratio is large enough for a sensible compromise to be visualized between cruising efficiency and reasonable approach speed.

In the early stages, de Havilland concentrated on Mach 1.2 long-range designs with swept wings, the so-called ‘M’-wing and delta-wing planforms. The M-wing form was also investigated by Vickers, Bristol and Armstrong Whitworth. Shorts looked at both medium-range and long-range transports with swept and delta wings at Mach 1.5 and Mach 1.8, while Handley Page studies featured delta, cropped-spearhead and swept wings at Mach 1.8. Avro concentrated on a medium-range, straight-wing Mach 1.8 transport.

The committee initially decreed that for the Mach 1.2 airliner, an M-wing or possibly swept wing would be preferable, while for the Mach 1.8 an integrated slender wing or long thin delta should be studied. At the time, total development costs of the Mach 1.2 design were put at £60–80 million, while those for the Mach 1.8 were around £95 million.

Politically, the SST emerged from the research laboratories and entered the political arena when, in May 1958, Derick Heathcoat-Amory, Chancellor of the Exchequer in the Conservative government of the day led by Harold Macmillan, reported the conclusions of an ad hoc inquiry into the future of the British aircraft industry to a Cabinet meeting in 10 Downing Street. The report concluded that fewer aircraft manufacturing companies were needed – and also warned that the development of the next generation of aircraft, such as supersonic transports, would almost certainly only be possible with substantial government assistance.

The first jet airliner in the world – the de Havilland Comet – seen in early July 1949, just before it flew for the first time. (BAe Hatfield/Darryl Cott)

Conservative Prime Minister Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton (b.10 February 1894, d. 29 December 1986).

Conservative politician Aubrey Jones (b. 20 November 1911, d. 10 April 2003).

Derick Heathcoat-Amory, 1st Viscount Amory KG, GCMG, TD, PC, DL (b. 26 December 1899, d. 20 January 1981) served as Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1958 to 1960.

This arose again in December when Jones, the Minister of Supply, reported that the country’s aircraft industry was in a bad way. He suggested that one way to strengthen it would be to resume the immediate post-war practice of providing government support for the development of selected aircraft, even those for which there was no immediate requirement. The largest project was likely to be the supersonic civil transport. The prime minister agreed, and said the Ministerial Committee on Civil Aviation should be reconvened to give further consideration to this suggestion.

At first the supersonic transport was regarded purely as a possible national venture, and Britain believed it had a head start in this race, just as it had a decade or so earlier with the DH.106 Comet jet airliner. Initial technical studies into the prospects for transport aircraft that would fly faster than sound had already begun. Then the idea that Britain might collaborate with the USA to develop and build a supersonic transport began to take shape in 1959. Both countries had SST research under way and were thinking about the possible development of supersonic civil airliners. The initiative for collaboration came from the British government.

One has to be careful in reading some of these contemporary reports, no matter how authoritative, for in some cases there are aspects of wishful thinking associated with them, in that what was reported never came even close to fruition, even to this day. For example, in the 12 December 1958 edition of The Aeroplane, Dr Robin R. Jamieson, chief ramjet engineer of Bristol Aero-Engines Ltd, emphasised the advantages of ramjets for supersonic airliners in a recent lecture before the Bristol branch of the Royal Aeronautical Society. After discussing the applications of ramjet power for propulsion at speeds up to Mach 5, he gave consideration to the types of ramjet which might be suitable for hypersonic flight up to Mach 12. He went on to say, ‘The superiority of the ramjet for flight speeds greater than Mach 2.5 led to Bristol studies of the use of ramjets for supersonic transports.’

American Developments

The American dimension was developed in a note Macmillan received from Harold Watkinson, his Minister of Transport and Civil Aviation. Watkinson had been talking supersonics with Lieutenant General Elwood Richard ‘Pete’ Quesada, chosen by US President Dwight D. Eisenhower to be the first administrator of the Federal Aviation Agency (FAA). Both men agreed that the airlines should have at least eight to ten years’ use of the existing subsonic jets before they were forced to buy supersonic machines, but they recognised that this would not necessarily happen.

Harold Watkinson PC, CH (b. 25 January 1910, d. 19 December 1995), British Minister of Transport and Civil Aviation.

Watkinson also reported that at the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) conference in San Diego, Britain had called attention to the big problems that would face civil aviation authorities if an SST was to come into operation within the next ten years, and had proposed that ICAO staff examine these matters. This suggestion had been supported by most of the other nations at the meeting but had been opposed by the United States. The US attitude made sense, the minister concluded, only if the Americans had already decided to proceed with a supersonic transport project of their own. This conclusion by Watkinson was coupled with the assumption that the American SST would begin life as a military project – as had the subsonic Boeing 707 airliner, which had ‘rode on the back’ of the KC-135 tanker, itself derived from the Boeing Model 367-80 – and would almost certainly come from the North American Aviation B-70 Mach 3 bomber wanted by Strategic Air Command, which would breed a civil version.

America’s answer to the Comet was the Boeing 367–80, seen at roll-out on 14 May 1954. Despite popular claims to the contrary, this was not the prototype Boeing 707 – although looking somewhat like it, it is in fact at least two stages away, having undergone two increases in fuselage diameter and other changes. (David Lee Collection)

Harold Watkinson thought that the cost of an all-British supersonic project would be enormous, and that it was doubtful if Britain could match the United States in straight competition. He suggested that the government should encourage British firms to set up a joint project with whichever US company won the SST contract.

Indeed, it was soon clear that Watkinson’s assumptions were correct, for by November 1960 the civil version of the B-70 was common knowledge. The British aeronautical magazine The Aeroplane and Astronautics ran a four-page article on the design, stating:

Transport versions of the B-70 have been studied and three different versions proposed. The first, which could be available by late 1963, represents the minimum conversion of the bomber.

By 1966 a more extensively modified version could be produced for operation by the Military Air Transport Service as a cargo and passenger transport. This aircraft would retain J93 engines, but would have a fuselage of greater diameter to improve volume, loading and operation. It would carry 107 military passengers. In the cargo role it would carry 75,000lb. for 2,470 naut. miles or 36,000lb. for 2,930 naut. miles. A commercial version could carry 80 first-class or 108 tourist-class passengers.

By mid-1967 it is considered that a competitive commercial transport could be produced. It would be powered by a turbo-fan version of the J93, and its fuselage and systems would be modified to permit FAA certification. Equipped with thrust reversers this supersonic airliner could operate from airports with a runway length equivalent to 10,500ft. at sea level. It would cruise at Mach 3 (1,980mph) at 70,000ft.

Operating costs have been calculated for transport B-70 operations during 1968. Assuming 3,000 hours utilization a year, and extrapolated currency inflation factors the cost will be 2.5 cents per seat mile for a typical transcontinental flight and 2.75 cents per seat mile for a transoceanic flight, assuming 90 passengers are carried.

When STAC’s 300-page report was submitted in March 1959, it recommended the design studies for two supersonic airliners: one to fly at a speed of Mach 1.2 and the other at Mach 2.0. The Ministry of Aviation acted quickly, with feasibility studies being commissioned for three aircraft types from the Hawker Siddeley Group and Bristol Aircraft in September of that year. A major change was that the proposed speed had now increased to Mach 2.2. The Hawker Siddeley Group was chosen to study an integrated wing, which was to be handled by its Advanced Projects Group, and resulted in a design with an all-up weight of 320,000lb and a wing area of 6,000sq. ft.

Concurrent with this, Hawker Siddeley also undertook joint studies with Handley Page into Mach 2.2 airliners. Bristol Aircraft were to study a slender-shape wing design with a distinct fuselage. Both companies were also asked to investigate a Mach 2.7 aircraft.

Lieutenant General Elwood ‘Pete’ Quesada (b. 13 April 1904, d. 9 February 1993), first head of the FAA in the US. (USAF)

A Flight by Boeing …

In early 1959, M.L. Rennell, the chief engineer of Boeing’s Transport Division, provided an insight into a typical Mach 3 flight from Paris to New York by a Boeing SST at a presentation given to the Institute of Aeronautical Sciences:

The flight takes off from Orly at 11.00hrs giving a local arrival time at Idlewild of 07.30hrs. The supersonic transport will be able to load, taxi-out and take-off in much the same manner as the subsonic jet. Near-capacity loads of about 150 passengers are carried.

Flight Planning: The optimum flight plan from the long-range cruise standpoint would require a climb to 65,000ft followed by a climbing cruise as fuel is consumed, reaching an altitude of 75,000ft just prior to descent. However, at the request of air traffic control the plan approximates the optimum cruise path by two constant-altitude segments, using an altitude of 68,000ft initially and 72,000ft for the second half of the cruise. The fuel load has to be increased by 0.8% of the take-off weight to cover this ‘step-cruise’ operation.

Climbing along the path for minimum fuel consumption, the aircraft would reach sonic velocity at 20,000ft about halfway to the coast of France, and the sonic boom heard on the ground would be objectionable over a considerable area. The climb-path will therefore be selected to reach sonic velocity over the English Channel, and the aircraft will be at 30,000ft when this velocity is attained; the intensity of the ‘boom’, therefore, will be substantially reduced. Fuel loading has to be increased by 0.4% for this off-optimum climb path.

Headwinds at cruising altitude are reported to be 50 knots, somewhat lower than the winds at the cruising altitudes for the subsonic jets. A 50-knot wind is fairly typical of winter weather at 60,000 to 80,000ft. The effect of wind is quite small for an aircraft of this type because of the short mission time. In this case the dispatcher has increased the fuel load by 0.7% to allow for headwinds, which prolong the trip time by only three minutes.

Reserve fuel requirements are based on CAR Regulation SR-427, effective October 1958, and provide sufficient fuel to fly an additional 10% of the normal trip time, plus diversion to the most distant alternate, plus 30 minutes’ holding at 1,500ft above the alternate. The alternate for this flight is Washington, D.C., and the reserve fuel required is about 8% of the take-off weight (compared with 5% for current subsonic jet transports).

Other possibilities to be taken into account are emergencies such as a cabin decompression, which would force the aircraft to descend to an altitude of, say, 15,000ft, where the cruise would be continued at a subsonic speed. If such a failure occurs more than 1,400 miles from the point of origin, with 8% reserve fuel, the aircraft cannot return to take-off point, and unless it has reached the 2,100-mile mark it will not have sufficient fuel to complete the trip.

However, should decompression occur halfway between Paris and New York the aircraft would still have a 1.100-nautical-mile range capability, sufficient to reach alternates such as Gander or Goose Bay. A similar situation exists with two engines failed.

Automatic Controls: Up to this point, the crew has encountered no problems different from those they experienced back in the 1950s. But, after take-off, they will experience a greatly compressed time in which to accomplish their jobs.

Designers and operators, therefore, are going to have to decide which jobs to give to the crews of supersonic transports and which to delegate to automatic devices. Greatest use can be made of the pilot’s analytical ability, memory and experience when he is used to monitor the general situation. The complete use of automatic controls must be approached with caution, however, and the pilot must be left with acceptable means of taking over and of practicing during regular airline operation.

The supersonic transport will undoubtedly have more automatic controls. However, it is believed that back-up manual controls, which meet the requirements for pilot proficiency, can and will be developed. Past experience must not be discarded by statements that a new era of control automaticity will accompany the advent of the supersonic transport.

Take-off and Climb: Take-off clearance is obtained prior to engine start. Take-off ground run is comparable to that of the subsonic jets, but somewhat greater due to the higher thrust-to-weight ratio of the supersonic airplane (0.35 as compared to 0.20 for the Boeing 707).

Long-range radar in the Paris air traffic control area will monitor the climb-out. The danger of collision with an intruder in the climb-out corridor is virtually eliminated because all aircraft will be required by law to maintain an illuminating radar beacon. The flight crew now have area surveillance in the cockpit as well as direct communication with the ATC long-range surveillance radar.

The pilot may elect to accomplish his climb by pre-programmed tape operating through the autopilot. Time to climb to the initial cruise altitude of 68,000ft and to accelerate to Mach 3 is about 15 minutes. In order not to exceed the cabin differential-pressure limit of 10.5psi, the cabin altitude is increased at a rate of about 500ft/min. During the climb and acceleration the relative slant of the cabin floor is about 12°.

En Route: The constant-altitude, constant-Mach-number cruise is easily handled by the autopilot. The pilot monitors cruise conditions and fuel consumption and, when the aircraft reaches the halfway check point, he initiates the climb to the second segment altitude.

Navigation equipment includes the best of that available on the subsonic jets, plus digital computers which avoid the necessity of the pilot solving a mathematical problem to arrive at his position, which is changing by about 30 miles each minute. Present position is automatically reported in code to recording equipment on the ground. Only occasionally is it necessary to use vocal radio contacts. All ground-to-air messages are received on the airborne radio-teletype, virtually eliminating the need for the pilots to take notes.

Of the emergencies with which the crew might have to contend, high-altitude decompression, as already noted, would require a rapid decrease in altitude to normal breathing levels. Pressurization of the cabin during descent would be accomplished by ram-air cooled with water spray. Oxygen service would be provided in addition to the ram pressurization.

One of the many versions of the early Boeing SST designs, this one being the Model 733. Again, the artist gives the impression that it is almost ‘above the atmosphere’. (Simon Peters Collection)

During the cruise, collision avoidance will be partially achieved by night-plan separation. The high altitude at which the supersonic jet cruises will keep it above other types. As a further protection against other supersonic aircraft an infra-red detector would be of use at the high cruise altitude, or a complete collision avoidance system such as that on which Boeing has been working for two years.

Terminal Clearance: At 700–800 miles out from destination the pilot will turn his attention to the terminal traffic and landing clearance problem. The pilot is faced with two possibilities in the terminal area which may alter his flight plan: re-routing to an alternate, or delays due to traffic or runway congestion.

The normal descent path is illustrated below. Fuel required to go to the alternate increases rapidly if re-routing is delayed until the descent has begun, so speedy Air-Traffic Control (ATC) approval or revised instructions are essential. Two descent paths could be used for programmed delays due to terminal congestion – ‘race-track’ orbiting on the normal descent path or earlier descent to a lower altitude followed by a subsonic cruise.

Before descending, the pilot will observe that his automatic computer has the intended descent path set into it, along with the aircraft’s position. He will mentally check that the computed time-of-arrival seems reasonable. This information will be automatically transmitted to the ground traffic-control receiving station, with a coded request for confirmation, if acceptable, or if not, for the minimum delay time which can then be programmed into the remaining cruise and descent.

Priority over other local slower flights would be desirable. The ground computer could recognise this priority from the coded identification in predicting the traffic and landing time.

The normal descent into New York, with a series of possible diversions into Washington DC. (Dulles)

The process of approach control could be carried out by a system whereby each aeroplane has its own self-contained navigation and code transmitting radio system, or by a long-range ground radar system utilising coded beacons in each aeroplane. The essential feature is that service from the ground traffic-control centre must be rapid. The report continued:

Descent: In order to eliminate any passenger discomfort, the rate of change of cabin altitude on the descent will be limited to 300ft/min. Since the cabin is at 8,000ft, this establishes minimum descent time at 27 minutes. Within this time, limitation of descent is scheduled so that minimum fuel will be burned, in order to be operating near maximum lift-drag ratio.

The speed schedule will be approximately as follows: first, the aeroplane is decelerated to Mach 2.2 at cruise altitude because the change in altitude for maximum lift-drag ratio is relatively small in this Mach number range. Next, an approximately linear variation of Mach number with altitude is followed until Mach 0.95 at 55,000ft is reached. Mach 0.95 is maintained down to the altitude for 300 knots EAS, and the final part of the descent is at 300 knots constant EAS.

In addition to the altitude/speed schedule, the pilot will fly in a definite corridor in the high-traffic-density areas near New York. Since the flight crew will have little time to work with paper maps and instrument procedure books the desired map will be projected on a screen in the cockpit, together with the aircraft’s position, determined from the navigation computer.

During the deceleration and descent the cabin floor will not exceed an angle of 5° nose down, which is comparable to that for a normal descent on the Boeing 707.

Landing: The best path to a straight-in approach will be used. If the weather is good the pilot will probably do the job manually, as this is a good time to practice. If the weather is bad, he may fly manually down the glide beam, but will probably put it on automatic so he can carefully monitor the overall situation. Automatic approach and landing will be handled by slaving ILS and autopilot to a ground computer which receives intelligence by looking at the aeroplane with K-band radar.

Scheduling: A possible flight schedule for a fleet of four supersonic transports would provide six Paris–New York round trips a day, with departures from Paris at intervals from 11.00hrs to 01.30hrs, and departures from New York between 07.00hrs and 16.00hrs, plus one at midnight. Arrivals at both ends are at reasonable local times.

Turn-around time is at least 2.5 hours for all but one flight on the New York–Paris run. Maintenance can be performed at either end of the line. Also, adequate time is available in either New York or Paris to accomplish overhaul on a progressive basis, and it should not be necessary to withdraw aircraft from scheduled operation for periodic overhaul.

This schedule would provide an average fleet utilization of 7.5hr a day. Long lay-overs by three aircraft at New York during the evening hours might be utilized for short north–south flights. For instance, three New York–Miami services each evening, for which the block time is 1hr each way, would increase fleet utilization to 9hr per day.

It appears that the supersonic transport can be scheduled to provide good daily utilization even with the small fleets which may be used when it first goes into service. As air traffic continues to expand, the larger fleet sizes which can be supported will provide more flexibility of scheduling.

Others had different ideas. Convair’s Vice-President of Engineering, R.C. Sebold, provided alternatives. A Mach 2 transport could be offered in 1965, but Convair favoured a Mach 3 to 5 transport for 1970. They saw no need for a major technological breakthrough:

The flight profile for the Paris-New York service as described by Boeing’s Transport Division.

Supersonic operation below about 35,000ft is impossible because of sonic boom effects. The faster the aeroplane, the smaller the percentage of trip distance that can be flown at supersonic cruising speed; speeds much above Mach 5, therefore, give small improvements on transcontinental or even transatlantic flights.

Based on 100% load factor, 3,000 hours’ utilization and 10 years’ depreciation, the direct operating cost of a Mach-3 transport, flown over 3,000n mile stages would be 1.63 cents/seat-mile.

In general, the smallest aeroplane that will do the job will carry the least fuel and have the lowest cost, although the larger the aeroplane, the lower its specific structure-weight. Broadly, the size might be: Span, 70–120ft; length, 170–230ft; and height, 30–50ft for a 135-passenger transcontinental transport. Powerplants are already in the design stage and will be conventional.

Temperature of the inside cabin wall must not exceed 90°F, requiring a 12in thickness of Fiberglass at Mach 4. Cooling by water-cooled air would reduce the weight of insulation by half, with a further reduction by using water directly to cool the cabin. A water-jacketed cabin might be possible, with the inner skin as the primary load-carrying structure in aluminium.

Rates of climb of 6,000ft/min are required to minimize fuel consumption, but the cabin rate of change is limited to 300ft/min. Cabins must be pressurized to 3,000ft or sea-level equivalent and a completely reliable pressurized vessel must be provided.

A closed-circuit TV system, with individual viewing screens, fed from an adjustable external camera, would probably weigh less than windows, which could be omitted with benefit to the pressure-cabin integrity.

Throughout 1959 a series of discussions took place between the British and the French at governmental level on the possibility of collaboration. Aubrey Jones held discussions with the French at the June 1959 Le Bourget Air Show. By September meetings had taken place between the Ministry of Supply and representatives of Bristol and Hawker Siddeley, both of whom argued against US involvement at that time, but they did feel something was possible with a European or Canadian collaboration. Later that year the industrialists suggested that while possibly more financially rewarding, a deal with the Americans would probably be more difficult than with the French.

The Spectre of a Soviet Threat

Over in the USA, pressure was being applied to the government to support the development of a commercial supersonic transport. The aviation press reported that the question of a subsidy for this development was being considered by the Aviation Sub-Committee of the Senate Interstate and Foreign Commerce Committee, under the chairmanship of Senator Almer Stillwell ‘Mike’ Monroney. To this committee, James Durfee, chairman of the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB), had addressed a letter claiming that Britain and Russia ‘… are known to be subsidizing the development of supersonic transport aeroplanes’ and that US manufacturers ‘may lose to foreign competition unless they receive prompt help and money from the Government’.

According to Durfee, a delay of one to three years in development by US manufacturers ‘might mean that some time in the early or mid-1960s the US long-range carriers may be forced by competitive reasons to place orders for supersonic aircraft in other countries. If this happens, the favored position enjoyed by US civil aircraft manufacturers might be lost for decades.’

Durfee went on to say that Boeing, Convair, Douglas and Lockheed could each turn out a supersonic model ‘given proper financial encouragement’. He stated that one of these manufacturers could have a prototype flying in about three years – given adequate assurances – and could deliver standard production models by about 1967.

Senator Magnuson said that Durfee’s letter confirmed his worst fears that America’s leadership in commercial passenger and cargo jet aeroplanes was in grave jeopardy.

There can be no doubt that it was the possibility of a Russian supersonic transport being developed which really worried the US industry and politicians alike – and the press suspected that this would almost certainly result in some form of subsidy being agreed upon.

The USA was still reeling from the shock of the Soviet satellite Sputnik, launched into an elliptical low earth orbit on 4 October 1957, and the first in a series of satellites that cumulated in the launch of Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin, who was the first man in space on 12 April 1961. The unanticipated announcement of Sputnik 1’s success – determined by anyone with a radio able to pick up the metronomic ‘beep beep beep’ of the satellite’s radio as it passed overhead – precipitated what became known as the Sputnik Crisis in the USA and ignited the space race within the Cold War. It fuelled American paranoia and fanned the flames of determination to show that America was ‘better’ than the rest of the world. The launch created a crash programme of political, military, technological and scientific developments.

That Russia, rather than Britain, was the nation’s concern, revealed itself in papers presented at the Second Supersonic Transport Symposium held in New York at the end of January 1960. Two of the four papers dealt specifically with the question of national prestige and the threat of competition; both mentioned Russia and neither mentioned Britain. ‘Unless as a nation we want to risk lagging behind the USSR in the introduction of supersonic transport … we must start an aggressive development programme without further delay,’ said P.J.B. Pearson and James Pfeiffer of North American Aviation.

The 1960 perception of the noise nuisance created by an SST on take-off and landing as demonstrated by Peter L. Sutcliffe of Hawker Siddeley. This was regarded as broadly accurate by all in the industry at the time.

The other paper – this time from B.C. Monesmith and Robert Bailey of the Lockheed Corporation – stated, ‘In the supersonic transport, the US has an opportunity to demonstrate to the World its technological leadership over the Soviet Union. In our opinion, the Government would be justified in supporting the development of a supersonic transport simply for national prestige.’

The American manufacturers, while waiting hopefully for a benevolent government to disgorge a few hundred million dollars, were not standing still. The extent of design studies and wind-tunnel research undertaken by Boeing, Convair, Douglas, Lockheed and North American was enormous: 14,000 wind-tunnel hours on Mach 3 configurations had been accumulated by the last-named company alone, to mention but one spot figure.

It is also worth underlining just one fact: in the considered view of North American Aviation, a prototype US Mach 3 airliner could be flying in 1963.

The view of North American’s Corporate Director of Development Planning J.B. Pearson Jr and R. James, manager of Commercial Aircraft Marketing, was contained in ‘Supersonic Transports – Considerations of Design, Powerplants and Performance’:

To provide a framework in which to consider the design, powerplant and performance of a supersonic transport, the authors of this paper postulated the following design requirements: range, 3,500 nautical miles with fuel reserves; cruising speed, Mach 2 to 3; cruising altitude, above adverse weather; passenger loads as dictated by economic factors; operating costs less than 3 cents per seat-mile; noise limitations comparable with present jet transport levels; take-off requirements, equivalent to a 10,500ft runway length at sea level.

A low-aspect-ratio (or narrow) delta-wing planform is suggested, with a fuselage length greater than that of present subsonic jet transports, in order to keep down the cross-sectional area and therefore the aerodynamic drag. A canard (forward tail) arrangement provides for the least drag at supersonic cruising speeds and results in the highest trimmed lift for take-off and landing.

A variable geometry windshield may be necessary, but there is a possibility that a low-drag fixed canopy can be designed to satisfy the FAA and SAE. Doors, escape hatches and windows can be designed to permit reliable supersonic operation at 80,000ft, but the windows in a typical 100-passenger transport would cause an increase of 4% in the gross weight (at a growth factor of 6) and might not be justified.

A choice is made in favour of buried engines, for reduced drag and reduced structural weight. Engines submerged in the fuselage, with tail pipes extending to the rear of the fuselage, offer the best solution. The layout thus described is, in fact, exactly similar to that of the B-70 and confirms that North American designs for a supersonic transport are based on this Mach 3 bomber.

A study of structural considerations shows that, up to speeds of about Mach 2.3, aluminium alloys may be used, but steel or titanium has to be introduced in various structural components above this speed and, by about Mach 2.6, must replace aluminium in virtually all parts of the airframe structure. The use of honeycomb sandwich is indicated by requirements arising from aerodynamic heating of fuel, low-aspect-ratio delta-wing planform, acoustical fatigue, and the employment of higher density materials.

Concerns Over Noise …

In a paper ‘Supersonic Transports – Noise Aspects with Emphasis on Sonic Boom’ by Lindsay J. Lina, Domenic J. Maglieri and Harvey A. Hubbard, of the Langley Research Center, it was clear that globally the airlines, manufacturers and research establishments were well aware of the problem of noise:

Three sources of noise – shock waves, aerodynamic boundary layer and engines – are of significance to designers and operators of supersonic transports, and the first and third of these are important also to the public at large. Tests to date indicate that a Mach 3 transport flying at 70,000ft may be audible on the ground over an area 70 miles wide along its flight path.

The sonic boom problem is the newest and probably the least understood. The boom (sometimes heard as a double boom) is produced by shock waves from the nose and the tail of the aircraft, and its intensity is influenced by several factors: Mach number, fineness ratio, body length, altitude (distance and pressure gradient), wind direction and velocity gradient, temperature gradient and a few others of minor importance.

Mach number is of small significance once the point has been exceeded where the boom is first produced; doubling the Mach number from 1.5 to 3.0 increases intensity by only about 26%. Much more significant is the distance between the observer and the flight path, both vertically and laterally; doubling the altitude from 30,000ft to 60,000ft reduces intensity by two-thirds. In tests with military aircraft the lateral spread of the sonic boom from 40,000ft at Mach 1.5 was found to be about 20 miles on each side.

Although sonic booms occur at Mach numbers slightly above 1.0, atmospheric refraction causes the shock wave to be curved sufficiently to miss the ground completely over a small range of speeds above this value. The exact ‘cut-off Mach number’ varies with temperature gradient, wind gradient, altitude and flight-path angle, and accurate atmospheric sounding or predictions will be essential for supersonic flight planning if advantage is to be taken of this cut-off point.

Changing the flight-path angle (i.e., climb or descent) rotates the whole shock-wave pattern in a manner equivalent to changing the shock-wave angle by changes in speed. Therefore, comparatively high Mach numbers can be achieved in a climb with no boom problems, but speed must be reduced in the descent to eliminate it. In tests, the boom produced by an aircraft climbing at 10° was only one-eighth the intensity for the same altitude and Mach number in level flight.

Some theoretical calculations (based on test results with military aircraft) have been made for a jet transport 200ft long, with a fineness ratio of 13, flying at speeds between Mach 1.2 and 2.0 between 20,000ft and 70,000ft. The damage threshold for noise pressures is assumed to be 2lb/sq ft, which is, therefore, the highest acceptable value for boom disturbance.

The calculations suggest that level-flight cruise above 60,000ft will be satisfactory, but that the climb and descent phases will need careful attention. This is an operating problem, as it is assumed that the aircraft will have been designed for minimum drag and no further aerodynamic refinements will be possible to reduce shock-wave noise.

A steep angle of climb will make possible acceleration to supersonic speeds at a lower altitude than would be the case for level acceleration (for reasons already explained). However, this technique brings the aircraft closer to the Mach cut-off number, which must therefore be assessed accurately for every flight.

Boundary-layer noise is important as a possible source of induced damage to the skin structure, as well as a nuisance to passengers. Surface pressure levels are significantly higher for the supersonic transport than for a Mach 0.8 transport, and noise damage could occur over the rear portion of the airframe surface.

A study of the possible engine-noise levels of a supersonic transport shows a danger of the present-day subsonic jet noise levels being exceeded, even though a 10° climb-out angle is assumed (double the present value). The turbofan engine does, however, promise to keep the perceived noise levels below the arbitrary figure of 112PNdB [perceived noise, in decibels].

Certainly it was not just the Americans who were aware of the noise problems – sonic booms and operating costs were the two key items on the agenda of an all-day symposium held at the Royal Aeronautical Society in London on 8 December 1960, as reported by The Aeroplane and Astronautics:

Noise problems are clearly exerting a tremendous influence on the design of the supersonic airliner. Noise produced during ground running and the take-off and climb affects the choice of powerplant, but nowadays this is not expected to be as much of a problem as the supersonic boom during the cruise. In the extreme this may compel countries to ban supersonic flying over land. If this happened, aircraft would probably need to be designed differently to cope with flying long distances subsonically.

Certainly it would have a very bad effect on operating costs which, even without this drawback, are unlikely to be competitive with operating costs of subsonic transports in 1970 when supersonic airliners are expected to enter service.

Members of Hawker Siddeley, the company which has not received a follow-on design study, made a particular point of this problem. It was introduced by Mr Sutcliffe [chief technician, advance projects group, Hawker Siddeley Aviation Ltd] in his talk.

He indicated that, even when cruising at 80,000ft, a supersonic airliner would produce a boom intensity pressure at ground level of between 1 and 2lb/sq ft. This is considered an objectionable noise, equivalent to close-range thunder and likely to cause some window damage. It would probably be unacceptable.

Messrs Morris and Stratford, also of Hawker Siddeley, took this point further by showing the effect on operating costs if supersonic flight over land were not permissible – for example, direct operating costs between London and Johannesburg would go up by about 50%. It was also shown how many airline routes, potentially suitable for supersonic operation, would be excluded, with consequent reduction in prospective sales for supersonic transports.

This problem is taken seriously by the airlines, as Mr C.H. Jackson of BOAC indicated. He showed a map of BOAC routes with operation limited to subsonic speed over all land which had a population density greater than 50 persons per square mile. This greatly curtailed supersonic operation and he felt that a decision on boom effect was vital, as it might decide which type of aircraft should be produced. The implications of this problem should, he thought, be decided before starting design work.

The suggested drastic influence of supersonic boom did not go unchallenged; both its magnitude and effect on people were questioned. Boeings have been very worried by this problem and their calculations of pressure rise and its effect tally with those of Mr Sutcliffe. But their studies show that 75% of air traffic for ranges above 2,000nm is over ocean routes or land areas with low populations, and they expect a demand for 50 supersonic airliners a year from 1968–70 onwards may be possible.

Sud-Aviation’s ‘Super Caravelle’ design.

Changes Within the UK

In a departmental reshuffle following the British general election of October 1959, the Ministry of Supply and the aviation part of the Ministry of Transport were combined to form the Ministry of Aviation (MoA) under Duncan Sandys as minister.