4,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: EDUCatt

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

In "Contemporary Ethiopia. State composition and human environment" Mattia Fumagalli ricostruisce la realtà politica dell'Etiopia contemporanea, ripercorrendone le fasi storiche che hanno portato alla creazione dello Stato africano, con un particolare occhio all'ambiente umano. Attraverso l'approfondimento di alcune delle più significative figure che ne hanno scritto la politica interna ed estera – come Menelik II, Haile Selassie, Meles Zenawi, Abiy Ahmed –, Fumagalli presenta al lettore un Paese che è oggi sempre più oggetto di attenzione internazionale per i suoi sviluppi sia politici sia economici.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

MATTIA FUMAGALLI

Contemporary Ethiopia

State composition and human environment

Milano 2022

© 2022EDUCatt - Ente per il Diritto allo Studio Universitario dell’Università Cattolica

Largo Gemelli 1, 20123 Milano - tel. 02.7234.22.35 - fax 02.80.53.215

e-mail: [email protected] (produzione); [email protected] (distribuzione)

web: www.educatt.it/libri

Associato all’AIE – Associazione Italiana Editori

isbn: 978-88-9335-919-1

This manuscript has been read by Jan Abbink, Leiden University,Netherlands; Researchers’ Assembly of the African Studies Centre Leiden; VrijeUniversity of Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Edizione realizzata a scopo didattico. L’editore è disponibile ad assolvere agli obblighi di copyright per i materiali eventualmente utilizzati all’interno della pubblicazione per i quali non sia stato possibile rintracciare i beneficiari.

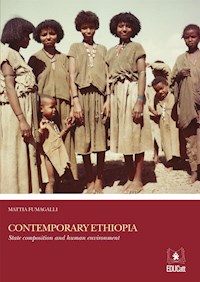

copertina: Sidamo, 1972. Photograph taken by my grandparents Eugenio and Bambina Fumagalli on the dirt road leading from Lake Awasa, in Sidamo, to the Comboni Catholic mission in Tullo. The picture depicts women from the Sidamo tribe in typical dress

Index

Index

Acknowledgements

Introduction and Methodology

Note on transcriptions and transliterations

Abbreviations

Menelik II: a narrative of his ascent to power

1.1 1872-1885: Negus1 Menelik and the pro-Scioan policy

1.2 From the occupation of Massawa to Dogali 1887

1.3 May 2, 1889: the Ethio-Italian Wuchale Treaty44

1.4 Clause XVII: the Rubenson-Giglio polemic and the Traversi thesis

1.5 Prelude to the Italo-Abyssinian War: diplomatic documents and the Mareb casus 1891

1.6 1895: Baratieri and the quid agendum

1.7 The Addis Ababa Treaty and the final act of Menelik II

1909-1930: the imperial dilemma

2.1 1913-1916: Ligg130 Yasu and the Muslim dream

2.2 Zeoditou and Tafari: the double-headed government

Haile Selassie the rise and fall of the last Negus Neghesti

3.1 Political organization of the state: federalizzare o sfeudalizzare162?

3.2 Fake elements of democracy: the 1931 constitution

3.3 The burden of slavery178

3.4 Foreign policy elements: the anti-European sentiment before 1935

3.5 The 1934 Wal-Wal incident and the Second Italo-Ethiopian War

3.6 1936: Mussolini’s loot: the Ethiopian Empire

3.7 1941-1960: the imperial throne is restored

3.8 An empire in decline: from the “national question” of 1960 to 1974

From the 1974 Provisional Military Government of Socialist Ethiopia to the 1993 Eritrean and Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF)

4.1 The concept of revolution in the case of Ethiopia: causes and developments

4.2 The era of Dergs and “Ityopia Tiqdem”

4.3 May 21, 1991: Mengistu’s escape to Zimbabwe and an Ethiopia changed for the better

4.4 From May 23, 1993 to 1998: the Eritrean dream of independence from Af Abet 1988

4.5 The TPLF: from 1975 to Meles Zenawi’s administration

4.6 The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia and the 1998 Ethio-Eritrean war

From the Federal Government to Abiy Ahmed Ali

5.1 1991-2005: the first and second federal governments

5.2 The developmental state and the 2005-2015 election issue

5.3 2018 and the Nobel Peace Prize of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed Ali

5.4 The three high-level tripartite summits: 2018-2020

5.5 Ethiopia, the Horn of Africa and the renewed international aspirations

Conclusion

Glossary

APA 6TH Bibliography

Primary historical sources

Secondary historical sources

Monographic texts

Journal articles

Monograph studies and periodicals

Tertiary historical sources: encyclopedia entries

Sitography

Conference presentations and lectures

Cartography and figures

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my gratitude and sincere thanks to Professor Beatrice Nicolini of Catholic University of the Sacred Heart of Milan, Italy, Faculty of Political and Social Sciences, my master’s thesis advisor and Ph.D. tutor, for her valuable advice on the writing, bibliography, cartography and use of citation styles: her deep passion for Africa has come down to me.

I thank Jan Abbink, Professor Emeritus Governance and Politics in Africa at Leiden University,Netherlands, President of the Assembly of Researchers of the Centre for African Studies Leiden and Distinguished Professor of African Ethnic Studies at VrijeUniversity of Amsterdam, Netherlands,whose advice on this monograph was essential.

This research and its publication have been carried out with the financial contribution of the Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, Milan, Italy, within its programmes of scientific research. Thanks to D.3.2, 2019-2021, research project “Evaluation of the Impact of C3S Model Agro-technological Innovations on Human and Social Development in Developing Countries (VICSUS)”, Faculty of Agricultural, Food and Environmental Sciences of the Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, Piacenza, Italy.

I also thank Dr. Judy Nagle, freelance proofreader and copy editor, for her painstaking editing from London.

I thank the staff of the Library of the Catholic University of the Sacred Heart of Milan, in particular Dr. Deborah Grbac and Dr. Giampiero Innocente.

I would like to thank Rossella Alessandra Bottoni, Professor at the University of Trento, Faculty of Law, my three-year thesis advisor, whose advice for a correct bibliography I will never forget.

I am grateful to my grandparents Eugenio and Bambina Fumagalli: even though you are no longer with us, your marvellous stories of Addis Ababa will always live on forever.

To all my family: our Africa is a memory that no one will ever be able to take away and will always remain in our hearts.

Introduction and Methodology

The choice of the subject of this thesis, namely its strong focus Ethiopia, has personal resonance: my family lived in Ethiopia for several years and my paternal grandfather had the honour of working personally for the Negus Neghesti Haile Selassié (1892-1975). Following the coup d’état of Mengistu Haile Mariàm (1937-) and the family’s return to Italy, Ethiopia remained in our hearts and through the stories and tales of this faraway land I developed a passionate interest in the country and a few years ago was able to visit it. My passion for the land has combined with a personal interest in analysing its geostoric and geopolitical reality. My methodological research has not included field research, which would certainly have given me better results, but instead I have opted, starting from my own existing family background, to use all the possible resources that we students are granted access to through the Catholic University Library Catalogue.

In terms of consulting the materials, exploring the online catalogues proved very productive: we proceeded with an analysis of the multidisciplinary electronic resources of the University Library, and then the Electronic Catalogue of databases and the Electronic Journal Catalogue. I was guided in the use of the online catalogues by the library staff and my master’s thesis lecturer, Professor Beatrice Nicolini.

The compilation of the bibliography was also conducted through the use of the Catalogue page of the RefWorks program, an online service for the management of bibliographic citation data and the automatic creation of a bibliography through the creation of a personal bibliographic database, only after obviously creating a personal account. RefWorks allows you to save RSS Fields to any personal email and uses the downloadable support of the Write-N-Cite feature. This was followed by text analysis on Jstor, the information retrieval system.

I consulted the online library catalogue of the Catholic University, using the so-called OPAC service, and external catalogues, as well as making use of the interlibrary document delivery and external deposit service.

The University Library contains various resources, among them many multidisciplinary electronic resources, or databases: Jstor, a bibliographic database with full text containing hundreds of academic journals and also ProQuest Social Science Journals. I have used these to search for single electronic journals in the electronic catalogue of the OPAC.

Through Jstor (i.e. the Electronic Resources/Database), I have been able to access the available periodicals online and then both the “manual electronic review” of the single journals, available through indexes of the single issues organised by year (i.e. Electronic Resources/E-journals), and the “automatic electronic review”, thanks to Jstor (i.e. Electronic Resources/Database); I have also subscribed to Academia, which contains many user profiles and provides worldwide connections, and Research Gate, which enabled me to find a lot of interesting material and connect with other knowledge creators.

Where I personally read a monographic text, I inserted the appropriate bibliographic citation correctly both by hand and using the online site WorldCat.org, which allows you to find missing bibliographic information.

In terms of research I found many archive sources relating to the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century which were precise, pertinent and detailed, as in the case of I documenti diplomatici italiani, i.e. Italian diplomatic documents, published by the Ministero degli Affari Esteri, i.e. the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs: these represent precious sources that help the scholar by describing the human environment as well as the composition of the state in Menelik II’s Ethiopia, but also in some cases of other nation states, since all the diplomatic documents are provided for years of publication. The monograph studies are more valuable and richer in information than the sitography, which is too vast, and often does not contain very much useful information. Colonial sources on the other hand, especially fascist sources from the time of the Italian occupation, provide a great deal of study material.

Note on transcriptions and transliterations

Names and toponyms in Amharic are simplified, with no diacritics, and are taken from the available sources consulted; common Amharic words has been rendered in their Anglicized form, without diacritics.

Abbreviations

COPWE: Organization of the Ethiopian Workers’ Party

ELM: Eritrean Liberation Movement

ENDF: Ethiopian National Defence Forces

EPLF: Eritrean People’s Liberation Front

EPRDF: Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front

EPRP: Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Party

FDRE: Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia

NCOs: Non-Commissioned Officers

OAU: Organization of African Unity

OLF: Oromo Liberation Front

ONLF Ogaden National Liberation Front

PDRE: People’s Democratic Republic of Ethiopia

PFDJ: People’s Front for Democracy and Justice

PGE: Provisional Government of Eritrea

PMAC: Provisional Military Administrative Council

TLF: Tigray Liberation Front

TPLF: Tigray People’s Liberation Front

Menelik II: a narrative of his ascent to power

Fig. 1.1

1.1 1872-1885: Negus1 Menelik and the pro-Scioan policy

In the 19th century, Yohannes IV (1837-1889), Negus2 of Tigray, installed himself on the Solomonic throne, having defeated the Ras3of Amara at Adwa in 1872: from this time on he would be known as Negus Neghesti, i.e. the Emperor of Ethiopia4.

The first official letters between the Kingdom of Italy5 and Ethiopia date back to 1872: through a particular intermediary, the priest Monsignor Massaia, who began his mission in Upper Ethiopia in 1859 for the then Count of Cavour – and then for Piedmont6, His Majesty King Vittorio Emanuele II (1820-1878) exchanged letters and gifts with the young Negus Menelik (1884-1913) of Shewa7. The young sovereign Menelik was, according to the Ethiopian language, a Negus of the Ethiopian vassal state of Shewa, which was subject to the central authority represented by the Emperor Yohannes IV (1837-1913), the Negus Neghesti, or King of Kings8.

In Menelik’s mind, friendship with a European power could provide him with the tools necessary for his rise to power and Italy thought the same: weapons, ammunition and money would help his plans to reorganize firstly the military apparatus in order to defeat the troops of Yohannes IV. In his eagerness he declared himself ready to accept Italian scholars and explorers who had wanted to visit Shewa. But when the Royal Italian Geographic Society appointed the old Garibaldian Marquis O. Antinori as head of the Kingdom of Italy’s first scientific mission, Menelik (1884-1913) was suspicious9. The Abyssinians were known at that time for their qualities of (transl.) «slowness, always ready to receive but reluctant, mistrustful, ambiguous» that delayed the completion of the Royal Italian Geographic Society’s construction of the railway at Let Marefià until 187810.

Menelik was successful in halting the advance of the Negus Neghesti Yohannesagainst Shewa in March 1878: in fact, the two great feudal lords – Menelik of Shewa and Tecla Haimanot of Gojjam – swore their allegiance on a formal and non-substantial level, i.e. livello formale e non sostanziale. This was the cause of Menelik’s rise to power: if the Negus of Gojjiam had preferred to remain isolated in his kingdom, Menelik had shown himself (transl.) «ambitious and restless, anxious to install himself on the Solomonid throne»11.

In return for his submission, Menelik received the recognition of the title of Negus, and the request was made for his daughter Princess Zewditu’s (1876-1930) hand in marriage for the son of Yohannes IV (1837-1889), Araya Selassié12. However, he had to accede to Yohannes IV’s request to remove Monsignor Massaia. This was (transl.) «his first great wrong to us [Italians]»13. His ragion di stato cost Italy a lot.

[...] the sacred selfishness that then inspired Menelik’s conduct should at least have trained us and made us watchful afterwards in the conduct of our pro-Shewan politics in which we instead became more and more engulfed, in the vain illusion that that sovereign, who had become powerful thanks to us, would then give himself to us as his protectors, and forgetting the wise Machiavelli according to whom «he who causes one to become powerful, ruins himself»14.

Yohannes IV (1837-1889) sought support in the province of Agomeder, paying the king homage in order to obtain his support. ForYohannes IV, a victory against the Dervishes15 would have increased his power, would have enabled him to receive greater gratitude from the Christians who lived here, would have allowed him to become the acclaimed saviour of Ethiopia and the one chosen by God. However, the attack against the Muslim population of Metemma with the defiant and tired Yohannes’ army proved fatal.

Menelik (1884-1913)’s self-proclamation as Negus Neghesti, with the name of Menelik II of Ethiopia, was supported by several provincial governors of whom he asked, and received, loyalty: the Gojjam, the Wollo-Galla and the Beghemeder16.

The pro-Shewan policy – which was against the interests of the other dignitaries of the Ethiopian empire, such as the Negus Tekle Haymanot of Gojjam17 – had the committed support of Earl P. Antonelli (1853-1901), who had drawn up the plan to ingratiate Menelik with the Italian people and to supply18 Menelik with weapons. Antonelli, however, received a welcome appointment from the Shewan court: on the death of the Italian Consul in Shewa, Marquis Antinori, on August 26, 1882, Antonelli became the official representative.

Earl Antonelli, as a diplomat19, helped Ethiopia and Menelik in the so-called process of leadership building, in the war against Mahdist Sudan, providing military cooperation, and therefore arms and money20, to Yohannes IV (1837-1889) and Menelik (1884-1913), guaranteeing the latter the line of succession to the throne at the expense of the Negus Neghesti21. It was Menelik himself – with the intention of inflicting the last hard blow on Yohannes IV – who asked Italy to create a diversion on the Eritrean border, inviting the Kingdom of Italy to occupy Asmara, to duplicate the threat on both the Mahdist Sudan and Eritrean borders.

From 1882 Menelik began to expand his territories southwards, initiating the offensive action against Gojjam that lasted until 1897. In these years, the Shewans defeated the troops of Harar, forced the Sultanate of Aussa to recognize its vassal status, received weapons from Italy, which gained them the upper hand through the superiority of their means of war over their opponents’ primitive spears, and finally the Shewans obtained from the countries subjected money, thanks to the heavy taxes, but also human capital, directly acquired through raids or the system of ghebbars22, intended to fuel the traffic of slaves23.

In 1883, Earl P. Antonelli, in his first diplomatic actions, provided 2000 rifles that had been promised to Menelik and obtained from the Sultan of Aussa, Mohamed Anfari, permission for the transit of caravans and couriers to travel from Shewa to reach the Port of Assab, in present-day Eritrea. In a letter dated 14 March 1883, the Sultan of Aussa wrote to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Rome:

As for the conditions, we let the negus Menelik determine them in agreement with Count Antonelli and we therefore wrote and sent our representative to Menelik. We have understood what envy and what intrigues tried to put evil between us and you; we accept with cordiality and with pleasure your friendship24.

Menelik’s joy led him to not hesitate to sign the treaty of friendship and trade proposed to him by Earl Antonelli.

1.2 From the occupation of Massawa to Dogali 1887

With the occupation of Massawa, Ethiopia entered into the logic of partitioning Africa, which reflected the strategic aims and the desire for grandeur in vogue among the politicians of the time, and which was granted legitimacy at the Berlin Conference of West Africa, a conference supported by Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, which proved an effective means for the participating nations to decide their territorial claims to portions of the African continent25.

Under Article 34, Chapter VI of the General Act of the Berlin Conference of 1885, it followed that the signatory powers could establish protectorates, subject to notification, where territorial possession had not yet been established. It reads:

Any Power which henceforth takes possession of a tract of land on the coasts of the African continent outside of its present possessions, or which, being hitherto without such possessions, shall acquire them, as well as the Power which assumes a Protectorate there, shall accompany the respective act with a notification thereof, addressed to the other Signatory Powers of the present Act, in order to enable them, if need be, to make good any claims of their own26.

Between 1884 and 1885 the Tigray moved against the Italian Bianchi expedition, carrying out a real massacre while the Mahdist Sudan threatened insurgence.

On February 5, 1885, Italy, in agreement with Britain – whose aim was to counteract a hypothetical German advance – landed in Massawa, the only natural port sheltered along the entire west coast of the Red Sea, as well as an object of desire and geostrategic outpost of the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean2728.

The Negus Neghesti Yohannes (1837-1889) was very alarmed: the port of Massawa was the only outlet to the sea in northern Abyssinia. For this reason, Yohannes forced the Shewan Negus Menelik (1884-1913) to eject the Italians. Yohannes was also aware of the Ethio-Italian relations maintained by Menelik and even if the latter permitted the passage of the Italians in Shewa, he had to surrender in the non-signature of the treaty of friendship and trade stipulated in 188429.

In 1886 the relationship between Ethiopia and Italy worsened: the exploratory mission of Earl G.P. Porro to the town of Gildessa – on the road from Zeila to Harar – was massacred. On January 10, 1887, Ras Alula ordered General C. Genè to leave the occupied positions in Saati and Uuà, 30 kilometres from Massawa, and on January 25 he suddenly attacked the garrison of Saati. The reserve column requested by General Genè was led by T. De Cristoforis. The battle of Dogali on 26 January 1887, fought with Italian bayonets and Ethiopian spears, resulted in Ethiopian victory and the death of T. De Cristoforis30.

Italy, with the agreement of Great Britain and France, had begun its campaign of annexation. The Italian objective of establishing a protectorate in Ethiopia was accompanied by the geographical expedition of Captain V. Bottego, which was sponsored by the Royal Italian Geographic Society and the Italian Government, and took place in 188731. His geographical interests did not go unnoticed by the Governor of Eritrea, General Major A. Gandolfi, who invited him to explore the interior territories. While the explorer was driven by the pursuit of scientific knowledge, the Italian and Eritrean governments had different plans. The exploration of the Juba River was an epoch-making event: the river strategically connected the Ethiopian plateau, where it rose, to the coasts of Somalia, near the port of Chisimaio, to where it flowed32.

In 1887 Menelik (1884-1913) signed a secret agreement of mutual assistance with Earl P. Antonelli and in exchange was to obtain much-desired weapons: five thousand Remington rifles33. With these weapons Menelik moved against Yohannes (1837-1889), who left Saati in the direction of Gojjam, having to pass through the Shewa.

Menelik, seen by Italy as an “ambitious, shrewd and yet still unprepared ruler”, was now indissolubly linked to it. He wrote to His Majesty Umberto I (1844-1900):

I promise and swear to Your Majesty that these weapons will serve only for the defence of my country and never to cause harm to Your Majesty’s subjects34.

In his vision of state consolidation Menelik therefore had a double plan, as Norok wrote in 1935 in the Journal of International Political Studies: «a minimum program: to make himself independent from negus neghesti, and a maximum program: to become negus neghesti himself»35.

During these years P. Antonelli presented the draft treaty, which was not signed until 1889 at Wuchale. Menelik’s support from and complicity with Italy allowed him to ascend the throne after the death of Emperor Yohannes IV at the hands of the Mahdists in the Battle of Metemma on March 11, 188936. In a letter of 26 June 1889 Menelik wrote to King Umberto I (1844-1900):

[...] an extraordinary and mournful event happened at Metemma. The Emperor John having descended with his entire army, fought against the dervishes, was defeated, wounded and died. [...], I beg Your Majesty to give orders to the generals of Massawa not to listen to the words of the rebels who were from the Tigré gate. [...] I would like the soldiers of Your Majesty to strongly occupy Asmara37.

In this letter we precisely find the central problem of Ethiopian unity38: the Negus of Gojjam and Wollo had already sworn allegiance to Menelik (1884-1913) and Ras MengashaofTigray still was a problem. MenelikII’s intelligence, actions and foresight had made Ethiopia, according to Earl P. Antonelli, an “impero senza eguali”, i.e. an empire without equal. Obviously not everyone recognized him as emperor: when the Ras Mengasha of Tigray did not show gratitude, Menelik asked the Italian army to invade the territories near Tigray and Asmara. The empire remained divided until Menelik II succeeded in imposing his presence over the powerful feudal lords of the north in his conquest of the imperial throne39.

Yohannes IV had exercised unquestionable supremacy and power, especially in Wollo. In terms of state consolidation, Ethiopia occupied Abyssinia and included several kingdoms: the empire of Yohannes IV was constituted by Tigray and his hereditary possessions. He obtained acts of submission in Gojjam, ruled first by Ras Adal then Negus Tecla Haimanot; in Agademer, ruled by Ras Alula; and in Wollo Galla, ruled by his godson Ras Micael and his son Areà Selassié40.

With Menelik II (1884-1913), however, the unparalleled empire, as P. Antonelli reported, included: Shewa, his hereditary possession, that of Tigray, that had belonged to Yohannes IV (1837-1889), which joined Amhara, that of Gojjam and of Shewa to which he aspired and in conquering41.

The aim of the Italian intervention was therefore to “try to assert in that troubled country our influence and our supremacy, harbingers of order, progress and civilization among those peoples that centuries of continuous wars and internal struggles had reduced to the most miserable and moral conditions of life”42.

The Italian policy, whose aim was state consolidation along colonial lines and therefore the affirmation of Italian supremacy rather than Ethiopian power, was also split: General Baldissera supported a pro-Tigrayan policy that exacerbated the internal divisions so as to justify the Italian dominion, in contrast to Antonelli’s pro-Shewan policy that would have seen a Negus Neghesti from the south ascending the throne. Before the signing of the Treaty of Wuchale, Earl P. Antonelli (1853-1901) wrote in 1889:

[...] (Menelik) will always have much to do to keep the restless Tigrines under his thumb: therefore he will always need our moral support and our friendship. He will therefore be pleased to see the Italians establish themselves strongly on the plateau, which will maintain our influence over the whole of Ethiopia, while if he were king of kings one of Tigre, even giving up today a part of that territory, the day he feels strong and absolute ruler of an empire, he will want to make popular with his fellow citizens, recover those countries ceded at a time of general disaster43.

Fig. 1.2

1.3 May 2, 1889: the Ethio-Italian Wuchale Treaty44

In view of these numerous successes, Ethiopia was presented with the famous bill of exchange, in gratitude for the help given to it. Throughout colonial history, treaties of protectorate have effectively represented “the epilogue or prelude of an act of force”, and the Treaty of Wuchale represented the compromise between Italy’s immaturity in understanding colonial expansion – especially at the governmental level – and the possibility of having the power to dominate East Africa45. Italian assistance to Menelik (1884-1913) in the so-called state consolidation of the Kingdom of Ethiopia was not in vain: as the Italian diplomat S. Romano wrote “The Italian government was delighted with the success of its political investment and came to collect the bill of exchange46 in the Treaty of Wuchale”47.

Fig. 1.3

A year later, the Empire of Ethiopia and the Kingdom of Italy agreed to stipulate a treaty of “friendship and commerce”48, in order to make “profitable and lasting peace between the two Kingdoms”49. The treaty was implemented by the Kingdom of Italy with the Royal Decree of April 10, 1890.

On May 2, 1889, in the city of Wuchale in the centre of Ethiopia, the Emperor Menelik II of Ethiopia (1884-1913) and Earl P. Antonelli (1853-1901) – commander of the Crown of Italy and knight of SS. Maurizio and Lazzaro – on behalf of King Umberto I (1844-1900), signed the well-known Treaty of Wuchale. Earl Antonelli found Menelik in a state of great excitement and gave him what he promised50.

Menelik II (1884-1913) was eager to receive protection from the Italian army, from the possible threat of not being recognised by the Ethiopian Ras51. With this treaty the northern Ethiopian territories of Bogos, Hamasen, and Akale-Guzai – which today correspond to Eritrea and the northern Tigray – were granted to Italy, which thus established it as a colony; in recognition, Italy granted Menelik a sum of money equal to one million thalers – through a loan negotiated with the Bancad’Italiaand with the guarantee of the Royal Government52 – and the supply of twenty-eight cannons and thirty thousand muskets.

It should be remembered that as Earl P. Antonelli wrote to the President of the Council and Foreign Minister Crispi (1818-1901), on 9 September 1889:

[...] Staying in Europe it is easy to compile advantageous draft treaties; the difficult thing is to get them approved by the kings of Ethiopia who were always afraid to bind themselves with pacts to a Civil Power53.

Italy was therefore happy to have been able to conclude a treaty of friendship with Ethiopia, which would bring peace and tranquillity.

Menelik, as friendly as he is to us, must reconcile our needs with his own in order to keep faithful the various elements of his people that he must govern. This treaty marks a first step forward that can be followed by many others, if we calmly and steadily follow an easy program that aims to give us with Ethiopia a period of peace and tranquillity * that has as its basis to be demanding only when we are determined to be powerfully energetic54.

The Italians then informed Menelik that if he wanted peace, he should give up the territories requested by Italy, namely Bogos and Asmara55. Unbeknownst to both Menelik II and P. Antonelli, Italian troops were already stationed in those territories at the time of the signing of the treaty.

The Italians and English relations differed in their approach to relations with Ethiopia: the Italians, in the person of Earl P. Antonelli, wished to respect the treaty and its good intentions, playing on the logic of the good friend it knew, while Britain – in the person of Admiral Hewett – was determined to sign the treaty with the firm military intent of joining forces with the Ethiopians in order to beat the Muslims. Hewett, not relating to Menelik II as a friend, ended up with a treaty that favoured only the latter56.

However, within the Treaty, Article XVII created many problems with regard to the Italian Government’s use of Ethiopia in its communications with foreign powers.

1.4 Clause XVII: the Rubenson-Giglio polemic and the Traversi thesis

Article XVII of the treaty in question appears to be the most critical and seven years later it would prove central to the Italo-Abyssinian war, which ended in defeat for the Italians at Adwa. Norok wrote in 1935 that this article, “which established the Italian protectorate over Ethiopia, was as timid and ambiguous as ever, and created a serious misunderstanding that only the force of arms could definitively settle”57.

Article XVII.

[...] the King of the Kings of Ethiopia allows the Government of [...] the King of Italy to use the Government of [...] the King of Italy for all business dealings he had with other powers and governments58.

The above article – in the Italian version – stated that the Emperor of Ethiopia “consents to avail himself of the services of the Italian government in all his foreign relations”, while the Aramaic text alluded to “may do so”59. There is still doubt as to whether the discrepancy was unintentional and caused by the language or was the result of bad faith on the part of Antonelli or his superiors in Rome, as Ullendorff suggested, rereading C. Giglio, Professor of History and Institutions of African-Asian Countries at the University of Pavia.

The figure of C. Giglio is crucial: in the Rubenson-Giglio controversy (that took place between 1965 and 1966 and which arose in response to Professor Rubenson of the University of Addis Ababa who in 1964 had written a similar article in The Journal of African History), Professor Giglio recalled how at the so-called internal level, there was no conception between Ethiopia and Italy of the protectorate, de jure or de facto. However, at the international level, that is, in relations between Italy and foreign nations, there was full recognition of the existence of this protectorate by virtue of the notification of the text of the treaty to a number of states. C. Giglio recalls that the basis is the text in the Aramaic language and that nevertheless P. Antonelli (1853-1901) should not be accused of bad faith, but simply of so-called carelessness. The so-called imbroglio, i.e. trick, as he defines it in Italian, after a careful examination of responsibilities, especially in the act of its notification – is attributable to Crispi (1818-1901)60.

According to Traversi’s thesis, “the emperor overturned the matter to his advantage”. The treatise, Traversi recalls, was signed in Rome and was later sent to the King of Shewa for translation.

Article 19. This treaty being drafted in Italian and Amharic and the two versions agreeing with each other perfectly, both texts shall be deemed official, and will in every respect be afforded equal faith61.

The culprit should therefore be traced back to the personal interpreter and translator of the Negus, namely the “famigerato grasmacc Josef”. But these theses, wrote Traversi, were not agreeable to the Negus: instead of punishing his translator, he blamed Italy and Antonelli, trusting in his ignorance of the language. A tradition therefore “combined between servant and master”62.

Earl P. Antonelli was thus replaced by Earl Salimbeni, who was sent out as General Resident after the signing of the Treaty in Abyssinia63.

1.5 Prelude to the Italo-Abyssinian War: diplomatic documents and the Mareb casus 1891

Clause XVII created many problems: Menelik (1884-1913) exploited Italy for his own ambitions, and having been betrayed, Italy had to face a bloody battle, the heavy cost of which was the well-known defeat at Adwa in 1896. Crispi was its first political victim: popular demonstrations forced him to resign.

From October 1889 to October 1896, therefore, at an international level, we can speak in the strict sense of Italy’s protectorate over Ethiopia.

On 5 October 1889, the secretary of the British embassy asked the Foreign Ministry for the content of the treaty. The Head of Cabinet Pisani Dossi, writing to the Secretary of the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Mayor, recalled that only the Minister could provide the exact information and that the contents of the treaty would be communicated to the other powers64. Thus, the treaty ratified between Italy and Ethiopia was sent to foreign powers, and the text of Article XVII of the Treaty of Wuchale was notified to these powers65. Crispi, as Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs, sent the following text to the Embassies of Berlin, Constantinople, London, Madrid, Paris, Petersburg and Vienna, and to the legations in Brussels, Copenhagen, The Hague, Lisbon, Stockholm and Washington. The following note mentioned the text of Circular 2388 of 11 October 1889:

Per l’articolo 17 del trattato perpetuo fra l’Italia e l’Etiopia firmato da S.M. il Re Menelik il 2 maggio 1889 e ratificato da S.M. il Re d’Italia il 29 settembre ultimo scorso fu stabilito che «S.M. il Re dei Re di Etiopia consente di servirsi del Governo di S.M. il Re d’Italia per tutte le trattazioni di affari che avesse con altre Potenze o Governi». Prego di notificare a codesto Governo la suddetta stipulazione a tenore dell’articolo 34 dell’atto generale della Conferenza di Berlino del 26 febbraio 188566.

The consequences were, to say the least, problematic: at the end of 1889 Antonelli wrote a confidential letter to Pisani Dossi, Head of Cabinet of the Minister of Foreign Affairs, warning him of the risk that the news might reach the ear of the Negus Menelik II:

The Temps note that the communication given to the signatory powers of the Berlin Treaty of Article 17 of the Italian-Ethiopian Treaty begins to make the rounds of the newspapers. The newspapers speak publicly and openly of the Italian protectorate over Ethiopia and this news will not fail to reach the ears of King Menelik who might believe, either that he was deceived by me, or that Makonnen betrayed him. In order to remove these causes of serious discontent, it will need to be explained to Menelik that the article was published in order to have more influence on the tasks that the king has given several times to the government of Italy both with regard to the issue of Lake Assai, and with the more recent one of promoting an agreement with the English government to keep the Dervish in subjection. To better substantiate this last statement, I think it would be appropriate to send Menelik’s letter to the English Government for H.M. the Queen and to promote a reply, whatever it may be, from that Government to present to Menelik67.

Crispi also decided to send a note to Cecchi, the Consul General in Aden, on 23 October 1889: Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom (1819-1901), receiving the letter from Menelik II, would thus have found an explanation for the well-known article XVII in which the Ethiopian state used the Italian one to communicate with foreign powers. This reality close to the international idea of the protectorate should have been denied in the presence of Menelik68.

The position of the United Kingdom informs us about the Italian expansionist aims, which seemed to be a doubt supported by the former. In a confidential letter sent on October 24, 1889, the President of the Council and Foreign Minister Crispi wrote to Commendatore Catalani, Chargé d’Affaires in London69:

In a few days I will send you an exact summary of the Ethiopian-Italian treaty so that you can confidentially bring it to Lord Salisbury’s attention. I prevent you from thinking that I am prepared to negotiate to have the British granted the commercial privileges granted to Italy in Ethiopia. She understands enough the importance of this matter for you to be able to convey it to the noble lord, who I am sure will easily be persuaded as to how our policy in Africa is to agree with the British70.

In a footnote to the above original text and in reference to the last line of “agree with the British”, it can be read “In T. 2554 of 25 October Crispi communicated to Catalani: “I authorize confidential Foreign Office communication of the Italian-Ethiopian treaty, provided that it will not be communicated to third parties... Please note that France has taken note of our declaration without reservation and without asking to know the text or the substance of the Treaty”71.

In a letter sent on October 31, 1889, from Catalani to Crispi, we read:

Salisbury told me that delay in taking note of our statement respecting Ethiopia was not his fault but the bureaucracy. His Lordship signs tonight a note to this embassy which will be dated the present twenty-ninth. The quotation from the Congo Act article can give rise to two observations: firstly, the article speaks of a protectorate, while relations between Italy and Ethiopia are not such in form, although they are in substance. Secondly, the article in question deals with territories by the sea and Ethiopia is in the interior. “However, these objections,” His Lordship has submitted, “do not prevent me from taking note of the notification received nor from being glad of the supremacy acquired by Italy in Ethiopia. I have repeatedly expressed to you in the most explicit way my mind on the matter. I want to add that after the occupation of Massawa, through Senator Pantaleoni, I advised the Italian government to open a road to the interior and to have the protectorate of Abyssinia as its destination. For my part, I am only concerned that British commercial interests should not be prejudiced and not in view of their importance but to avoid complaints from Parliament72.

Lord Salisbury’s aim was therefore to recognise Italian supremacy in exchange for the recognition of commercial privileges. It should be added that in the name of this promise, as mentioned in the confidential letter, Salisbury then authorized the Foreign Office to make known to Catalani privately the wishes of the British government.

As far as Russia was concerned, Crispi took care to send a letter to the Chargé d’Affaires in St. Petersburg, Bottaro Costa, dated October 24, 1889:

[...] she can say that Russia should be pleased with the new position we have acquired in Ethiopia, not least because it is in the character of the Italian government not to meddle in religious matters and to leave all beliefs, including the Orthodox one, greater freedom to practice them73.

Returning to the British position, Lord Salisbury and Crispi succeeded in concluding a very precise agreement concerning Ethiopia and its economic, social and political balances. In a letter dated November 4, 1889 Crispi replied to the British Chargé d’Affaires in Rome, Dering, about the trafficking of arms and ammunition in East Africa:

[...] the purpose of the proposed convention now seems to be no more than to deprive the Sudanese insurgents of the means of prolonging a struggle that hinders all trade in a vast and fertile region of Africa and threatens to deprive it for many years in a state of barbarism. [...] the King’s government saw [...] which was to be understood in the agreement, which was simply to regulate the arms trade, a different order of stipulation concerning the Harar, and that, subsequently, the project to extend the ban on imports of arms and ammunition to the Oppia Sultanate was put forward. [...] the Royal Government could not today, after the new relations with Ethiopia and the order of things established by a regular treaty [...] contract with third parties, with regard to Ethiopia itself and its dependent countries, any commitment that would undermine its right and duty to provide both for the arming of its garrisons on the plateau and for the internal and external security of Ethiopia itself, an allied power of Italy, and for whose external relations Italy has the care and responsibility. If [...] for a truly useful purpose, such as preventing the dervishes from being supplied with arms and ammunition, the King’s government will gladly sign it, provided that no reserve [...] is made for war purposes in favour of lead and sulphur. As for the Harar, we do not see the purpose of special pacts concerning a region which, like the Uollo-Gallas, belongs by legitimate right of conquest and occupation to a sovereign friend and ally of Italy. The right of the Emperor of Ethiopia to the Harar is neither disputable nor challenged74.

Italy seems to have responded harshly to the British demands, agreeing positively where the English action is aimed at not arming the dervishes, but showing opposition where the demands are directed towards Harar for its reserves of lead and sulphur.

On November 19, 1889, a letter from Buckingham Palace, on behalf of Her MajestyQueen Victoria of Great Britain and Ireland (1819-1901), was sent to the Emperor of Ethiopia, Menelik II (1884-1913):

[...] We have received the letter which Your Majesty addressed to us in the month of May of this year, and in which, whilst acquainting us with the melancholy death of His Majesty Johannes, late King of Kings of Ethiopia, you inform us that you have inherited the throne of Ethiopia. We [...] convey to you our congratulations upon your accession to the throne, together with our best wishes for the prosperity of your Reign. As regards the matters [...] of the dervishes, we shall not cease to use all our efforts to secure the peace and well-being of the regions in question, in concert [...] with our friend, His Majesty the King of Italy and with Your Majesty [...]75.

On 23 November 1889 Crispi asked Antonelli for one last great effort – already verbally agreed in advance – requesting his presence in Ethiopia for the signing of a supplementary agreement with the King of Kings of Ethiopia not so much to ascertain the borders of Ethiopia, in terms of consolidating the state with the accession of Menelik II, as in the interests of Italy and its borders.

[...] The mission you were given last year to King Menelik was accomplished with a zeal and success equal to the trust that I have in you, and I cannot but thank you and praise you most heartily on behalf of the Royal Government and myself. But your task is not yet finished. It remains, as you know, for King Menelik to sign an additional convention, to ascertain our borders, to establish good neighbourly relations and lasting friendship with Ethiopia. [...]76.

On December 19, Crispi (1818-1901) wrote to the Emperor of Ethiopia:

The treaty concluded between Italy and Ethiopia, as well as the additional convention intended to complete it, and which will be submitted to Your Majesty for ratification, closes the period of struggle between Italy and Ethiopia. A future of peace and tranquillity is now opening up before us, which will be able to give rise to more advantageous undertakings which will be more conducive to the prosperity of the two peoples. My King’s government is animated by the desire to contribute to peace and the consolidation of the Ethiopian Empire. It will therefore take every care to remove all dangers which might disturb the peace and quiet and make the exercise of its sovereignty less secure for Your Majesty. This vigilance of ours will be all the more active towards those countries where Your Majesty’s troops are fighting the Mahdist Revolution, and we are pleased that the weapons that Italy has given to Ethiopia, rather than being used as war instruments against Christian populations, serve to defeat and destroy Muslim fanaticism77.

Italy had therefore used Great Britain and other powers to secure control of Ethiopia but at the same time made Menelik II believe they were protecting him from external interference and continued to court him with weapons sent to Ethiopia to fight the Mahdist cause.

At the end of 1889, on 26 December, Ambassador Marochetti wrote to Crispi (1818-1901). The principal problems relating to Ethiopia were the definition of the border and the achievement of a solid international image:

From today’s conversation with Giers [...] agreeing with me that Turkey has no valid territorial claims on the Red Sea, he objected that if the limits of those possessions were more than badly defined, so too was the concept of Ethiopia. All this, however, is only secondary; the real reason for Giers’ reluctance must be sought in the impossible situation in which he finds himself with regard to the Sacred Synod, which looks ill on the interference of a third power in the secular relations between Russia and Abyssinia. Giers begs V. E. to observe that he marked receipt of our communication with an official note [...] and does not intend to protest or interfere in Italian-Ethiopian relations. For these reasons he instructed Uxkull to confine himself to simple verbal observations [...]78.

For Italy all this represented the first great colonial enterprise of the rejuvenated Italy, but for Ethiopia the pressure grew. In September 1890 Menelik II repudiated the Treaty, denouncing it in its entirety in 1893 and stating that the text translated into Italian was incorrect and that the Amharic text stated that Ethiopia could use Italy’s offices for the conduct of foreign affairs. In fact, in 1890 Menelik violated the provisions of the Treaty: in protest he notified his accession to the throne to the foreign powers, without the intermediary of the Italian Government. Menelik (1818-1901), understanding the situation, wrote in February 1890 to King Umberto I (1844-1900):

Having sent the news of my accession to the throne to the friendly powers of Europe on the occasion of my coronation, I found in their replies something humiliating for my kingdom. The reason derives from Article XVII of the Treaty of Wuchale. [...] we have found that there is a lack of conformity between the content written in Amharic and the translation into Italian79.

Menelik was not wrong: in the letters sent to Queen Victoria of Britain and to the Emperor of Germany, the young Negus Neghesti was reminded that any “communication between Abyssinia and the Powers had to be made through the Italian government”80.

In October 1890 an irritated Menelik II wrote to Umberto I: in the letter he communicated his great disappointment that the Italian text of the treatise did not correspond to the Amharic one81. The government of Crispi contested the Abyssinian interpretation with equal disappointment, telegraphing “I am determined not to compromise on Article XVII communicated to all of Europe”82. That verb proved critical for relations between Ethiopia and Italy, a “a thorn in the side of Italian colonial politics” as the Italian Diplomat Sergio Romani wrote83.

Italy ordered the invasion of northern Ethiopia, beyond the border established in 189084, and in the same year Ethiopia had to surrender over the border with Eritrea85:

[...]. Yet in 1890, he was forced to yield to Italian demands for a new boundary with Eritrea. This gesture of appeasement on his part, however, was to no avail, as Italy continue to make advances into Ethiopian territory86.

It is important to note that the policy of the Negus was based on a so-called “appeasement”87: but proceeding down the road of pacification agreements was not the answer. Italy was determined to move forward. Menelik protested, but basically ignored the invasion: his objective remained to import firearms in large quantities and France and Russia were able to satisfy him. The second objective, no less important, was to consolidate the borders of the Ethiopian state.

Fig. 1.4

The removal of Crispi’s mandate on 31 January 1891 did not mark great differences in foreign policy: while Crispi was a determined colonialist on the one hand, the new Minister A. di Rudinì appeared not to be but in fact he decided to continue to support the commitments made previously: on 24 March 1891 he signed a protocol with Lord Dufferin to outline the Anglo-Italian influence in East Africa. The protocol marked the border starting from the Juba River, and according to the latitude and longitude agreed88, placed Ethiopia de facto within the Italian sphere of influence. Menelik II was not informed and the only thing he could do was to assert the borders of ancient Ethiopia and be ready to defend them.

In 1891 Menelik II (1884-1913) sent an official declaration to the heads of state of Great Britain, Germany, France, Russia and Italy, asking them for the necessary support to claim his state territorially. Menelik II’s statement read:

I have no intention of remaining an indifferent spectator, while the distant Powers are determined to divide up Africa, since Ethiopia was for fourteen centuries a Christian island in a sea of pagans. Since the Almighty has protected Ethiopia to this day, I hope that he will protect and enlarge it in the future, and I do not think for a moment that he wants to divide it among other Powers89.

It is interesting how, far from being an indifferent spectator, the Negus’s first position is centred on a willingness to act, to respond. He reiterates that Ethiopia was a so-called Christian island for fourteen centuries. The first fact reminds us of the geographical position that enabled isolation and external attacks, while the second reminds us of the uninterrupted religious condition that for fourteen centuries fostered the achievement of a cultural and religious unity. With reference to the term Christian island, it is necessary to remember that the first quality of Axum, the symbol and seat of religious authority, was precisely isolation90.

In the past the border of Ethiopia was the sea. [...]. Today we do not pretend to regain our coast by force, but we hope that the Christian powers, advised by our Saviour Jesus Christ, will restore our borders, or at least give us some outlet to the coast91.

In thisdeclaration there does not seem to be a willingness to use force but only a hope for the restitution of borders. The outlet to the coast refers without a shadow of a doubt to the Italian annexation of the port of Massawa92 – on the Red Sea – in 1885, which saw the loss of the only Ethiopian outlet to the sea and the landing of a thousand Italian military units.

Italy, in order to take possession of the coast of Somalia, formed the Italian Company of East Africa and notified the Sultanate of Zanzibar of its decision (having set its sights on this area).

In 1891, the Ras Mengasha of Tigray– who did not recognize Menelik as Negus Neghesti – addressed “proffers of friendship” to the Italian Government: on December 8, 1891, the so-called Mareb conference was organized in which the Ras of Tigray met with the then Governor of Eritrea General Gandolfi93.

Menelik was quick to assume Italy’s willingness to help and support the Tigrayan Ras in his rise to power. At the same time, to deny the conference would have meant to open Italian hostilities against Tigray.

On May 3, 1895, the Minister of Foreign Affairs Baron A. Blanc, at the behest of King Umberto I (1844-1900), signed a so-called agreement with the Royal Italian Geographic Society to support Bottego, providing the latter with a grant of 100,000 lire, 60,000 lire being provided by the Italian Government and 40,000 lire by King Umberto I, while the Society, on the other hand, assumed responsibility for the organisation of the expedition94. While the expeditions served to discover the interior of the country, for Menelik they represented a worrying threat, particularly in respect of the British. It reads:

On October 17 [1894], Smith wrote a letter to the emperor [Menelik II] explaining [...] the purpose of his journey was purely scientific. Unknown to Smith, such a declaration was unlikely to persuade Menelik, who was keenly aware that his imperial aims in the Lake Rudolph region could easily be jeopardized by agents of European powers masquerading as scientific travelers95.

1.6 1895: Baratieri and the quid agendum

The period of hostility between Ethiopia and Italy began for various reasons: Italy, from 1890 to 1896, with the support of Great Britain had tried to establish a protectorate, increasing military goods and financial transactions; there was more and more court intrigue, with the idea of Menelik expelling Italy and allying with France and Russia96, who had legations in the country and would provide him with the necessary weapons97; the textual misunderstanding of Article XVII led to the denunciation of the Treaty98; and finally Ras Mengasha’s defeat at the hands of Italy, who had also been courted by Menelik for “stirring up the minor leaders of the Eritrean Colony”99.

In 1893 Crispi (1818-1901)’s intentions were undoubtedly directed towards the conquest of Ethiopia. In 1894 General Baratieri, who succeeded General Gandolfi, defeated Bata Agos and succeeded in suppressing the revolt in Eritrea.

On December 25, Baratieri decided to march on Adwa, crossing the border with 3500 men and carrying out an offensive against Ras Mengasha. The Tigrayan population seemed shy: in the words of the Commander-in-Chief we can read that when the Coptic priests presented crosses to be kissed, some leaders were respectful. Everything seemed to be in favour of Italy and this enterprise, which was never anti-Christian, but aimed at preventing conflict and imposing peace100.

After the defeat of Mengasha, Italy could follow different paths. In the analysis of the quid agendum, that is, of what to do, Italy wondered whether a political-military action in East Africa was necessary in order to forcefully impose the Italian protectorate or whether to carry out the withdrawal of the troops in Eritrea, paying for the victory achieved and accepting the denunciation of the Treaty.

Italy’s problem was essentially a matter of responsibility: the resolution was political and not military, and therefore it would have been up to the King’s Government. But the telegrams reveal incomprehension: the Government referred to the judgment of the Commander of the expeditionary Corps – who wanted to tentatively invade the Tigre and the Agamè –, who in turn referred to the military Commander. While Ras Mengasha was being strengthened militarily, even asking for help from Shewa, Italy was in crisis: with state consolidation in mind, it was at this moment that Ethiopia found the united force to defeat Italy, which was divided between the popularity of the company abroad and its unpopularity at home. On an economic level, the costs were very high: the budget of the colony which was to be 13 million lire, and the reduction of the proposed budget of 9 million would have involved the repatriation of three Italian battalions and the dissolution of two indigenous battalions101.

On December 7, 1895 Menelik succeeded in convincing all the leaders of central Ethiopia to move from Shewa against the troops of Major Toselli at Amba Alagi. Toselli managed to defeat them and Ras Makonnen102, captain of the avant-garde, hastily claimed that it had not been his order to attack Amba Alagi. In this military frame, there were also Abyssinian attacks on the Makallè fort. The lines chosen were good from a tactical if not logistical point of view: the roads were steep and narrow and did not allow the pack animals, the so-called beasts of burden, or carriers to pull their loads. Many camel drivers fled so as not to fall into the hands of robbers. The supply from Massawa slowed down, causing concern. They had almost no choice but to fall back on Adwa103. Crispi’s “clairvoyance and patriotism” was aware of the “narrow-mindedness of the political exponents of what was not wrongly defined the Little Italy”104. He sent General Baratieri in support of General Baldissera but – due to the timing – Baratieri decided to declare war.

Fig. 1.5