Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

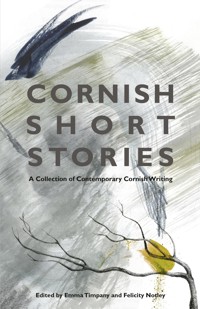

Ghosts walk in the open and infidelities are conducted in plain sight. Two teenagers walk along a perfect beach in the anticipation of a first kiss. Time stops for nothing – not even for death. Sometimes time cracks, disrupting a fragile equilibrium. The stories are peopled with locals and incomers, sailors and land dwellers; a diver searches the deep for what she has lost, and forbidden lovers meet in secret places. Throughout, the writers' words reveal a love of the incomparable Cornish landscape. This bold and striking new anthology showcases Cornwall's finest contemporary writers, combining established and new voices, including: Philipa Aldous, Cathy Galvin, Anastasia Gammon,Tim Hannigan, Clare Howdle, Adrian Markle, Tim Martindale, Candy Neubert, Felicity Notley, Sarah Perry, S. Reid, Alan Robinson, Rob Magnuson Smith, Katherine Stansfield, Emma Staughton, Sarah Thomas, Emma Timpany,Tom Vowler, Elaine Ruth White.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 251

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Cover design © Vita Sleigh, www.vitasleighillustration.com

Vita Sleigh has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, to be identified as illustrator of this book cover design.

Woodcut illustrations © Angela Annesley, www.ravenstongue.co.uk

Angela Annesley has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, to be identified as illustrator of these woodcut illustrations.

First published 2018

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

Selection and Introduction © Emma Timpany & Felicity Notley, 2018

The right of Emma Timpany and Felicity Notley to be identified as editors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All content is copyright of the respective authors, 2018

The moral rights of the authors are hereby asserted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

The content of the stories are entirely fictional and any resemblance to actual persons living or dead is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 8822 3

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed in Turkey

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Introduction

Talk of Her KATHERINE STANSFIELD

Roaring Girl ALAN ROBINSON

An Arrangement TOM VOWLER

Beginning Again CANDY NEUBERT

Sonny ROB MAGNUSON SMITH

The Superpower SARAH PERRY

The Haunting of Bodmin Jail ANASTASIA GAMMON

The Siren of Treen EMMA STAUGHTON

Ballast SARAH THOMAS

I Run in Graveyards CLARE HOWDLE

The Maple is in Blossom CATHY GALVIN

That Same Sea ADRIAN MARKLE

Home Between Sea and Stone TIM MARTINDALE

The Hope of Recovery ELAINE RUTH WHITE

I Turn on My Own Axis FELICITY NOTLEY

The Kiss PHILIPA ALDOUS

A Bird So Rare EMMA TIMPANY

Too Hot, Too Bright S. REID

On the Border TIM HANNIGAN

Notes

Acknowledgements

The Contributors

INTRODUCTION

AS WE put together this collection, we were determined that the stories we chose would not simply reach for familiar tropes – rugged cliffs, romantic beach scenes and pasties – but would have sprung from felt experience. They needed to be true both to their writers and to Cornwall. When a seagull does fly in from the wide blue yonder, as in Rob Magnuson Smith’s masterful story ‘Sonny’, it instantly becomes both more than itself and exactly what it is, inscrutable behind its yellow eyes.

Writers are often solitary but can flourish when brought together. We both feel fortunate to have discovered Telltales, a live literature event based in Falmouth, where writers share their work and socialise over a drink or two. It was through Telltales that Nicola Guy from The History Press – herself from Cornwall – found us and invited us to edit this new anthology. Nicola had some rules for us to follow: the writers included must be Cornish by birth or upbringing or must live in Cornwall. Cornwall also had to feature as a setting in the stories themselves.

The work of this current generation of Cornish writers is hard to classify; nothing is clear-cut in this far-flung place. The many legacies of Cornwall’s industrial and maritime past still visible in the region have informed a number of the stories. Elaine Ruth White’s ‘The Hope of Recovery’ takes us diving deep to a wreck beneath the waves of our dangerous coastline. Sarah Thomas’s ‘Ballast’ pays tribute to Cornwall’s presence on the world map in the great age of sail, a time when explorers and naturalists, including Charles Darwin, passed through Falmouth’s natural deep water harbour. The stories create their own map of Cornwall: from the Tamar to the Helford, from Bodmin to Penzance, from Launceston to Zennor.

During the submission process, many retellings of traditional Cornish tales surfaced. Emma Staughton’s ‘The Siren of Treen’ – a melodic reworking of ‘The Mermaid of Zennor’ told in three voices – stood out, as did emerging writer Anastasia Gammon’s ‘The Haunting of Bodmin Jail’, an original and witty take on the classic ghost story.

Given Cornwall’s long history as a source of inspiration for artists, we felt the visual design of the book should reflect this. Elemental forces in the cover design by Vita Sleigh and in the woodcut illustrations by Angela Annesley resonate between the contemporary and the traditional, rather as modern life and a rich literary heritage feed into the writers’ words. Vita described the inspiration behind her design as follows:

My approach was to use colours which I felt expressed the essence of Cornwall: wild, often grey (the sea in winter, stark cliffs, the turbulent skies), earthy with splashes of colour (the bright green that mosses can be, the yellow of gorse flowers, the deep almost tropical blues of the ocean on those rare but gorgeous Cornish days).

The image of the wind-blown tree was something I came back to again and again in drawings. It is what I thought of first when I saw the brief. I liked the idea that the tree has been shaped by the Cornish landscape and weather, in very much the same way that the writers will also have been heavily shaped by living in this sometimes harsh but beautiful area of the world.

Whilst Cornwall’s past never feels far away, Candy Neubert’s ‘Beginning Again’ is set very much in the present, detailing the intricacies of a father–son relationship on an idyllic Cornish beach. The liminal space between land and sea is also the setting for ‘The Kiss’ by Philipa Aldous, where a girl and boy walk together, full of anticipation for the moment that will surely come. More complex relationships are the focus of Tom Vowler’s exquisite and moving short story, ‘An Arrangement’, and S. Reid’s beautifully wrought tale, ‘Too Hot, Too Bright’. The shifting boundaries between fiction and poetry are explored in Cathy Galvin’s richly layered prose poem, ‘The Maple is in Blossom’.

One of the defining characteristics of Cornwall is its separateness: there is joy to be had in crossing the Tamar from east to west. We are delighted that Tim Hannigan has allowed us to include in the collection his inspired, numinal piece, ‘On the Border’ – a deeply-felt exploration of place and time.

We’ve chosen to open this book with Katherine Stansfield’s poem ‘Talk of Her’. The ‘her’ in question is Dolly Pentreath, the last native speaker of the Cornish language.

Emma Timpany and Felicity Notley

Cornwall, 2018

TALK OF HER

KATHERINE STANSFIELD

They say she spoke no English as a maid

hawking fish in Mousehole. They say

she was found by the language man

as if she was lost, that the day he came

she was raging. He thought her curses Welsh

at first, then caught something else.

A witch, they say, and Cornish

her tongue for witching. They say

she was wed and unwed. They say

there was a child, a girl, though some

say a boy, say he died. By the end

she’d prattle anything for pence. They say

she was the last to speak it, but listen –

there’s others here still talking, and when

I dug her up last week, forty-seven feet

south-east from the spot they had marked, her

with three teeth in that cracked and famous

jaw, I tell you, she spoke just earth and water.

ROARING GIRL

ALAN ROBINSON

SHE WAS the first person I saw at the festival as I entered the tea room, flooded with light from the domed glass ceiling, which showed fluff on her black velvet jacket and britches. She looked up as I approached.

‘Is it Eileen?’ I asked.

She smiled. ‘Aileen.’ Emphasising the A.

‘I’m Jack.’

‘Sit down.’

‘Can I get you a tea or something?’ I asked. She was sitting at the table like a sprung coil, looking as if she wanted to get away quickly.

‘I’d rather have ale,’ she said. ‘Or better still, mead. There must be loads of mead around these parts.’

I couldn’t place her accent, which sounded like Suffolk mixed with cockney and even some Irish. Nor could I tell her age. She looked girlish yet old, prematurely grey hair bobbed like a boy’s. She was both dandyish and slovenly: her ruffled lace shirt matched the velvet suit perfectly, but was a bit torn.

‘I’m sure we can get mead. Follow me.’

Her eyes lit up, a burnished blue, and tiny dimples appeared in her cheeks.

‘Now you’re talking.’

‘Have you been here long?’ I asked as we walked down the hill from the tea room to the meadows, passing the main house where early festival machinations were taking place on the green outside, lots of women in wellies with Cornish accents bossing men about. It was understatedly alternative.

‘An age,’ she said.

‘I’m sorry. My train was a bit late. Then I walked straight past the entrance to Port Eliot. It’s more or less a hole in the long garden wall.’

‘Which one of these tents has the mead?’ she asked.

‘The big one,’ I gambled. I knew it was the beer tent, but not if it had mead. It did.

‘You’re a star,’ she said, when I handed her the glass.

‘Cheers.’

‘This is a big show,’ Aileen said. ‘I’ve never seen so many people in a tent except at Royal Regattas.’

‘Have you been to many?’ I asked.

‘A few,’ she said. ‘You have to. I get on quite well with some of the courtiers. They say the Queen likes me.’

‘Thanks for meeting me,’ I said. ‘I’ve brought a CD which explains a bit about myself and the story. I thought it might help to listen to it when you’ve got a moment. I know you’ll be busy here.’

She took the disc, turned it over with a blank look and put it on the bar. She then put her mead glass on it.

I didn’t know what to say. I sipped my beer, spluttered into it, then said, ‘I also have the story in print,’ and took a copy of my book’s introduction from my bag.

‘Manuscript: that’s what I’m used to. It’s a bit thin though,’ she said. ‘Did you write it yourself? Maybe you should get help.’

I welcomed these put-downs as par for the course with star-rated literary consultants, as well as, if I’m honest, the dominatrix-ish frisson I sensed between us.

‘Anyway, I’ll have a look at it later. Tell me a bit about yourself,’ she said.

I summarised my patchy writing career, titivating the most promising bits, and hoping to sound edgier than my subject matter.

‘You didn’t say anything about money, like what you were paid last, or what you wanted for this, but if you’re a new boy I guess you just have to take the crumbs, am I right?’

By this time I’d truly lost my voice. I nodded.

‘Thanks for showing me the mead house. I’ll have a look at this tonight.’

‘Thank you. I hope you enjoy it. Where shall we meet?’ I called, as she moved off.

‘Here, same time tomorrow.’

That night I tried to find and bump into her. Port Eliot’s not so big that it couldn’t quite easily happen. I looked for her velvet suit, but as it grew dark that was difficult even in the beer tents, and I hoped I would just run into her on a path through the trees, or on the moonlit walk along the riverbank. I came across only lovers and midnight swimmers, unaware of my presence, so that by the end of the night I began to feel like a ghost.

I wondered if she’d read my manuscript by now, and if it was a hit, or if she’d binned it and wouldn’t turn up on Saturday to give me feedback.

After midnight passed, I gave up hope and followed the raised voices and slews of people heading for the Walled Garden. Under a marquee at the far end an Irish band was mixing every kind of world music to an Irish backbeat, the yells and whoops of performers and crowd growing more insistent as I came near. It was cold on the edge of the crowd, and to get warmer I pushed through until I was a couple of rows from the front. There she was, tambourine in one hand, a drink in the other, still in her black velvet suit, shirt collar undone, a determined look in her eye as she kept time. It was a family affair, and she seemed to be part of it, or a close friend, winking at a young girl guitarist in the band who was a little hesitant, urging her on. The song finished unexpectedly on an upbeat, the discipline of the finish taking the audience, including me, by total surprise. I blinked twice, and when I focused again, after my eyes had swum from woodsmoke and beaconing stage lights, Aileen had gone. There was a gap next to where the young girl musician stood with her guitar, looking lost. A lostness I shared.

It was pitch black away from the lighted tents. I walked along pathways beneath trees, numb and still exhilarated from the music. As the sounds everywhere damped down, there was nothing to do but find my tent and sleep.

Before I was due to meet Aileen the next day, I went to a writers’ open mic, a semi-serious affair in a small tent in a grove of trees. I thought it would help me loosen up before my meeting. She was there, in an identical velvet jacket and britches, this time bottle-green, reciting a pub-song-cum-verse-drama, which reminded me of women blues singers whose records I’d heard from the 1920s, a riot of double meanings and sexual innuendo. It was a Rabelaisian hoot. She went down well, sandwiched between a couple of gawky lads whose stories were of self-loathing and self-love.

I followed her down the slope away from the trees, glad to see she was heading for the mead tent where we’d agreed to meet.

After getting drinks, I was about to ask if she’d been able to read my piece, when she said, ‘The first thing is that you should stop writing about yourself, for Christ’s sake. Choose someone famous or mythical, and forget prose. Why isn’t it in at least iambic pentameter? And it has to be a play; at the moment it’s like a long letter to no one. What do you say to that?’ She took a sip of mead.

Dry-throated, I spluttered back that I respected her opinion but was trying to do something experimental with the prose.

‘We all resort to a bit of loose prose every now and again, even Will Shakespeare,’ she said. ‘But plays are what entertain people. Think about what I’ve said. We’ll talk some more, but now,’ she drained the mead, ‘I have to go and see the Queen.’

I followed her at a distance after she left the tent, out of sheer curiosity. I knew the Queen couldn’t actually be there, even though she looks as good in wellies as the next person.

When I caught up with Aileen she was bowing to the Queen of Hearts in a children’s pageant in the woods. She said, ‘Majesty, may I have your ear?’ and whispered something, after which the Queen pronounced: ‘Clear the court, we must see a play!’

Aileen performed a one-woman play within a play about two star-crossed lovers and their goblin aides, both funny and moving, enthralling the kids and their mums and dads and me.

Afterwards I caught her eye, as she watched the end of the pageant from the far side of the audience. I smiled. She saw me, but turned away and walked towards the river.

That night I blotted her out, and her critiques. I told myself they were the rattling of an East End trendy who never set much of a foot outside London. Why come to these things and agree to see budding writers if you had no intention of nurturing them? For the free invite, no doubt, and the expenses. I got into Guinness, which simultaneously helped with the blotting out and made me feel more substantial.

I ended up at a gig in the music tent, which I came to halfway through. I could have sworn it was Bob Dylan in his Nashville Skyline period but on the way out heard someone say, ‘He was just like his dad,’ so surmised that it had been Dylan’s son. I headed for the riverside walk, entranced by the fairy lights and thinking – still gobsmacked by the Dylan Junior gig – of reincarnation.

I got lost and stumbled on an open-air cocktail bar in a glade that played soul to die for. I sensed Aileen had been there – or maybe I just sensed her everywhere that weekend – and got to dancing and drinking with two women of Aileen’s generation. They knew the moves. We had a good laugh, took selfies. I found for some reason I’d drunk myself sober and went back to my tent to re-read my manuscript. At that hour, approaching early dawn, it alternated between being genius and dross, often on the same page.

Wide awake and restless, I headed for the river across the meadows. The estuary birds would reassure me with the inhuman prescience of their calls; it had worked before.

The open-air cinema screen was still up, though now it was a blank white sheet, and a few all-night stragglers were still winding one another up with tall stories and meanderings among the wisps of mist suspended above the waterside.

Along the estuary there was a boathouse towards which I was walking. As I got near, I saw a boat swinging fast, driven by oars, headed for the boathouse. It glided in, and Aileen stepped forward to the end of the jetty. I hadn’t seen her until the last minute, recognising first her bottle-green velvet of the day before, and then her boy’s hair, as she stepped gingerly into the boat. I wanted to hurry and say goodbye, or please ring, both of which would have been equally inappropriate. She was going to wherever she’d come from, in the Hollywood manner in which she seemed to do everything, and she hadn’t given me her card.

I walked back to the tent wearily. The manuscript was on its back, the last page turned over underneath it. There was some handwriting on the page, in a scruffy, spidery, blue-inked script. It said: ‘Look me up if you’re in London. I’m the original Roaring Girl. You can find me at the Mermaid Tavern in Fleet or my lodgings at Cheapside.’

Her last joke, I thought.

Next day, on the train out of Port Eliot, I was flipping through the photos on my camera. I came to the one I’d selfied at the cocktail bar after midnight and stopped. There were three women in the photo, one at the back with short bobbed hair, barely visible. It could only be her.

When I got home I Bluetoothed the photo to my computer and blew it up. The third woman had gone. But I had an email from the writers’ consultancy I had contacted before the festival, which contained a profuse apology from them that Eileen had been unable to come to the festival, and would I send them my manuscript by email?

I emailed back to say that I had decided to write a play.

AN ARRANGEMENT

TOM VOWLER

IT IS one of those late summer evenings only Cornwall can yield – heady and languid, yet the county’s slender form determining that the air will always be brackish, nautical, wherever you are. The garden’s drowsy scent marshals in me nostalgia for the dozen or so Augusts we have spent here, seasons laid down deep in the brain’s circuitry, more felt than known. Of droning bees, drunk on one of the colossal lavenders behind the old rockery, the day’s heat subsiding yet still irrefutable. I picture the summerhouse – where swallows nest each year, where we would converge as afternoons lapsed, to imbibe each other’s days – its exterior, I am told, in disrepair. And beyond this, quilted fields with hedgerows of yellowing hawthorn, the sparrow-haunted rowan richly berried, fragrant walks that should have been more prized at the time.

The low sunlight illuminating my wife’s shoulder as she sits at her dressing table is somehow both mellow and scalpel-sharp – some trickery of the new medication, I suppose, which, whilst inhibiting some of the pain, distorts reality a few degrees. She is precise in her movements, a well-honed routine to enhance a beauty that was, she insists, late to flourish and which is only now perhaps beginning to wane. Men age so much better, she is prone to say accusingly, although perhaps there is altruism here, in case on some level I am still preoccupied with how handsome or otherwise I remain. I want to speak, to deny the reminiscing further indulgence. Not because of her imminent departure, an exploit that has occurred monthly for the past year; but because there is something to be marvelled at in this dance we are able to perform – it would be simple for her to get ready in another room – as if my involvement, albeit one of mere observation, is somehow vital, consensual. Some months she even solicits my thoughts on a particular dress, a combination of jewellery I think works best, and I advise with due sincerity, delicate in my judgement, fulsome in praise. Perfume, though, is her realm alone, as if it speaks to a level of intimacy neither of us can endure, its selection seemingly flippant, a final flourish of decoration rather than the olfactory manipulation it aspires to be. Whether she imparts more scent than at the times we dined out together is hard to say; perhaps further adornment takes place in the taxi, a courtesy extended to me, one of several that have formed unbidden.

‘You can ask me anything and I will tell you,’ she said at the start.

‘I know.’

And I have been tempted. Not from a rising paranoia or raging jealousy. More that I wonder if hearing such detail would arouse me on some level, allow a vicarious lust to play out. But I don’t ask. As lovers in our thirties, I would have torn open any such rival, or at least threatened to, confronted him with animalistic fury before collapsing a tearful wreck. Such confrontation is beyond me now, but I sense no real desire for it. I am not so naïve as to mistake this for some Zen-like enlightenment, or worse still a Sixties openness to communal loving. I always wondered how that played out in reality, unadulterated by the rose-tinting of hindsight. Was everyone who partook accepting of such frivolous hedonism, the sharing of orifices and organs, or was homicidal behaviour only kept at bay narcotically?

‘Are you okay?’ she asks. ‘You seem distant.’

‘I was just thinking,’ I lie. ‘Do you regret not having children?’

This isn’t a fair question and could be construed as my attempting to mar her evening.

‘Oh, darling, we’ve spoken about this.’

‘I know, but you might have changed your mind.’

We were trying, right up until I became ill, which I suppose was rather late in life, at least for a woman. Careers had consumed us, the time never right. And then when it was: not enough blue lines in the little window. Tests showed no reason for our fallowness; it was simply a matter of perseverance, of sending enough seed swimming in the right direction. But the next batch of tests we endured – I endured – were of another order entirely.

‘I’m content,’ she says. ‘I don’t really think about it these days.’

Absent of all segue she speaks of the dinner awaiting me, cauliflower cheese, that she’ll bring it in as she leaves. I make a joke about it being my turn to cook, but it’s an old, well-worn line and goes unacknowledged.

‘You’ve got your baclofen,’ she says.

‘Yes.’

‘And you can take more naproxen at ten o’clock.’

‘All two of them.’

Six months ago, when my mood found a new nadir, I began hoarding pills, with no more intent than to experience the sense of control it offered, some small reclamation of autonomy. Ever since she found them, their administration has been piously governed.

‘You never ask me,’ I say.

‘What you want for dinner?’

‘Whether I regret not having children.’

She sighs, a minute outbreath escaping despite herself.

‘Can we talk about this when I get home?’

‘Will that be before or after the sun is over the yardarm?’

I can’t help myself. I don’t even feel the level of spite it implies; it’s as if I want to try it on – being a shit – like a jumper.

‘I can’t cancel now. We agreed. If you don’t want me to go, you have to give me a few days’ notice. It’s courteous.’

This word seems to me inappropriate, their arrangement requiring a more squalid lexicon.

‘I want you to go,’ I say. ‘I can sort myself out if you pass me some tissues.’

‘Please don’t be crude.’

It’s true, I can just about, still – yet the thought fills me with weariness, the exhaustion of the thing, my mind the only reasonable place for sex to occur these days, and then only from habit. In the early years of incapacity we continued to make love, content in its gesture however unsuccessful the deed itself. And later, when this became impossible, she would use her hand, whisper lewd contrivances that led more to despondency than climax. Abstaining came wordlessly, a relief to us both.

And so my emasculation was complete. A man, in any true sense of the word, no longer. Whilst hardly the athlete, it has always been the loss of physical rather than cerebral activity that I’ve felt more keenly. Who’d have thought batting at ten or eleven, plus eight overs of regulation off-spin for the village side, ranked higher in my sense of worth than an associate professorship? Nothing like total debilitation to provide a little perspective.

The blurred vision came at the end of a stressful week, where rumoured redundancies became reality, our department likely to bear the brunt, and so the early symptoms were neatly aligned with events at work. Medicine, I have learned, is a patient creature, never rushing to judgement, content in the knowledge time will out. And so a series of hoops must be passed through, each one narrowing, each one ruling out potential, less condemning causes. None of this was helped by my mild but well documented hypochondria, which in the end even I clung to. Tingling or numbness? Almost certainly nothing of concern, came the counsel. Fatigued? Aren’t we all? Even the disturbed balance prompted only rudimentary scrutiny, blood tests, talk of an MRI. But after the first seizure a neurologist thought it prudent to tap my spine for some of its fluid, a joyous procedure, which suggested my body, far from suffering the slings and arrows of modern life, had in fact turned on itself. Later a new vocabulary evolved: bedsores, converted bathroom, managing expectations.

My wife stands and checks herself in the mirror, turning ninety degrees left then right, a look of satisfaction rather than vanity.

‘I’m sorry,’ I say, and she crosses the room, kisses my forehead, the Chanel still young, yet to blend with her own scent.

‘If you’re awake when I get back, I can read to you if you like.’

We are tackling my favourite Márquez, all 450 pages, most of which I won’t remember, at least not this time round. But the essence of the book lingers in the suburbs of my mind, and so despite my attention wavering every few lines, there is still pleasure to be had. Pleasure especially in the sound of the words, my wife’s voice a blend of honey and whisky, a balm no painkiller can rival. I wonder what texts the students have been given this term, what anodyne classics have been selected for their enrichment, novels chosen by committee to illustrate technique or theme, rather than to delight in. A couple of colleagues visited in the early days, bearing gifts and conversations that groaned with formula, office gossip their stock offering. Better off here, they would say, away from it all. Certainly I was accommodated for in those final days at work. Reasonable adjustments, as they’re termed, were made as symptoms advanced: a parking space, pressure on fire doors eased, reduction of hours. I worked from home when possible. I knew all my work was re-marked, that I was just humoured in the end.

My wife moves the Márquez onto the bed, placing it in the space she will later fill, a promise of sorts. I smile, knowing the pills will render me beyond storytelling later tonight. In her absence I will listen to the radio, a surprising source of company that I’ve neglected most of my life. During the worst relapses, when mobility is nothing but fantasy, entire days can be built on the scheduling of programmes from around the world.

I try to remember the first occasion the matter of her taking a lover came up. Curious verb that, more something you associate with a hobby, the taking up of a pastime. Which lover would madam like to take? Have you browsed our online options? Just click Add to Cart when you’re ready. I know nothing of him, no particulars beyond a handful of unsolicited revelations: age (around ours), profession (middle management), marital status (widowed). So he at least waited, I thought.

‘Just tell me he doesn’t play golf,’ I said. ‘I couldn’t stand that.’