Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

On a bright July morning in 1870 the British explorer George Hayward was brutally murdered high in the Hindu Kush. Who was he, what had brought him to this wild spot, and why was he killed? Told in full for the first time, this is the gripping tale of Hayward's journey from a Yorkshire childhood to a place at the forefront of the 'Great Game' between the British Raj and the Russian Empire. Driven by 'an insane desire' Hayward crossed the Western Himalayas, tangled with despotic chieftains and ended up on the wrong side of both the Raj and the mighty Maharaja of Kashmir. Tim Hannigan explores the conspiracies and controversies that surrounded his death, travelling in Hayward's footsteps to bring the story up to date, and to reveal how the echoes of the Great Game still reverberate across Central Asia in the twenty-first century.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 596

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Acknowledgements

First thanks are due to my agent, Robert Dudley, for his sterling efforts, and to Simon Hamlet at The History Press for commissioning the book. Thanks also to Lindsey Smith and Christine McMorris at The History Press for the editing.

Thanks to the staff and archivists of the Royal Geographical Society’s Reading Room, for showing great patience at obscure requests, and especially to Sarah Strong. The same thanks are due to the staff of the Asian and African Studies Reading Room at the British Library, whose public can be even more trying.

Sincere thanks to the doyen of Great Game writers, Peter Hopkirk, for allowing access to a copy of Hayward’s Turkestan journal previously in his possession, and for being kind enough to take an interest in the project (and thanks too to Kathleen Hopkirk for the emails).

The greatest debt of gratitude is owed in the lands through which Hayward travelled. Thanks to various Kashmiri truck drivers and Indian tourists who gave rides to a bedraggled hitchhiker in Ladakh. On the other side of the Karakoram thanks to – amongst others – Abdul Wahab in Kashgar, and to Abdul Latif for company and driving skills on the doomed attempt to reach the valley of the Upper Yarkand. In Pakistan thanks always to Yaqoob and Habib and everyone at the Madina Guesthouse in Gilgit for hospitality and help over the years, and thanks to the incomparable Mr Beg for tall tales of Partition and the Gilgit Uprising.

Heartfelt thanks to everyone who treated me so kindly in Yasin, especially the valley’s magnificent schoolteachers: Ghayas Ali in Sandhi, and Mohamed Murad and Abdul Rashid in Darkot.

Elsewhere, thanks of course to Edhita. And finally, the biggest thanks of all to my family for everything, especially to my father, Des, for taking me to Pakistan the first time and for filling my head with stories.

Contents

Title page

Acknowledgements

Maps

1 Death in the Morning

2 Into the Wild

3 From Forest to the Frontier

4 A Most Unsettling Companion

5 Fugitive on the Upper Yarkand

6 The Way they Treat their Guests in Turkestan

7 The Road is Full of Stones

8 Speak, or Die Bursting with Rage

9 Strange and Suggestive

10 Hayward’s Curse

Chapter Notes

Bibliography

Index

Plate section

Copyright

Maps

1

Death in the Morning

The man had not slept all night. It was summer, but 9,000ft up in the high mountains of the Hindu Kush it had been cold during the hours of darkness. Now in the first blue-grey light before dawn, exhausted and hungry, he shivered. It was 18 July 1870.

He had arrived at this high campground the previous afternoon with his little party of servants and a group of surly local porters. For two days he had been moving slowly up this narrowing, steep-walled valley, with many a nervous backwards glance: he had leftYasin, the main village, on bad terms and these mountains were lawless and violent. He was far from any government or authority that could protect him, and he knew only too well that in this cold, rocky valley he was stripped of the privileges his nationality would afford him elsewhere. He was an Englishman – the first ever to reach this wild and stupendously remote spot, far beyond British territory, beyond even the troubled western frontier of Kashmir.

Only as he had moved further fromYasin the previous day had his mood lightened: the temperature had risen and a yellow haze softened the sharp edges of the vast peaks that towered over the valley. Though he was not moving at the scorching pace that he usually maintained, no one seemed to have followed him. No one had delayed his progress, and now, finally, he seemed on the brink of leaving all his recent troubles behind; tomorrow he would cross the high pass at the head of the valley and be gone from this troublesome territory. What was more, once he had passed that watershed he would at last be within striking distance of the very place he had been trying to reach for the previous two years: the High Pamirs; the Roof of the World; the unknown upland wilderness at the locked heart of Central Asia.

The valley was beautiful in a raw, almost violent way – this was a landscape of extremes. In the narrow bed there was green amongst the tumbled boulders, little terraces and patches of goat-cropped grass. The watercourses were lined with thickets of willow, in full leaf at this time of year, and there were ranks of slender poplar trees, bending and whispering in the running breeze. As the little party had pressed on upwards they passed occasional small villages of rough stone walls and flat roofs, stepped up the brown hillsides in uneven tiers. Sometimes the smell of wood smoke and pine sap or the sound of voices and the calls of goats drifted across the valley, and there were figures – broad-shouldered women in heavy skirts and bright skullcaps – at work in the little fields. Beyond that the land soared upwards, first through patches of threadbare pasture, and then into a vertical wasteland of fractured red-brown rock and scree. The great mountain walls towered higher and higher, into wind-scoured black buttresses and onwards into steep faces of permanent snow, glittering icy yellow and blue in the midday sunlight.

By late afternoon, when he pitched his rough canvas tent on a hillside below a stand of trees, the man had begun to relax. The day had passed without incident; he looked forward to the steep climb to the pass and anticipated the summit’s great swelling view to the new country beyond. The local porters had downed their loads and wandered off bad-temperedly, but the man was unconcerned: he could find new men to carry his baggage in the morning. From here the journey would be physically tough but, he hoped, things would be less politically fraught.

Yet as the light lengthened down the valley, flaring the high peaks with gold and dropping slabs of blue shadow on to the lower slopes, one of his servants brought alarming news from the nearby hamlet of Darkot: he had been followed. A large group of armed men had trailed him all the way up the valley from Yasin. They had told the villagers that they had come to accompany the man over the pass, but they did not join his little camp nor even try to contact him. They were out of sight, hiding somewhere in the thick, scrubby forest, and the man was sure that they had sinister intentions.

The apprehension of the past days came rushing back, all the more intense now after the calm interlude. With a feeling of hollow nausea in the pit of his stomach the man realised the hopeless vulnerability of his position. There was no longer a chance for a quick about-turn back into less dangerous country.

Light fades very quickly after sunset in the high mountains, and in the heavy, blue stillness as the sky pales behind the ridges, sound carries a long way. Broken voices in the village; goats bleating as they were hurried down from the high pastures; and the noise of the stream, busy with meltwater from the curving glacier to the west, drifted up the valley to the lonely little campsite. Great smears of stars began to show in the rough-edged patch of sky. The man could hear his own heart beating.

He had no appetite and he declined his servants’ offer of food. The five men who accompanied him – four servants and a munshi, or secretary – must have felt every bit as nervous, and all the more powerless, for they had simply followed him to this exposed place. Far from home, he had made their decisions. They were Kashmiris and Pashtuns, hard men from the lawless hills of the North-West Frontier, but this was not their country and they had good reason to be afraid. As the darkness came down, thick and heavy, the little group prepared for a miserable and lonely night, knowing that somewhere out of sight, somewhere on the hillsides or among the trees, men were watching them.

The man knew that he must not sleep. In the hours of darkness the rules change: awful things happen and men do deeds they would never do in the hard, judgemental glare of daylight. If evil was to befall him, the man was sure, it would do so before dawn. If all was well at sunrise, there would be hope. Anyone wishing to do him harm might hesitate then, and if he pressed quickly onwards with the same brash confidence with which he had left Yasin village perhaps it would carry him unscathed to the pass and beyond. What mattered now, more than anything, was that he must not sleep.

It was a long night. The man had loaded his rifles, taken his pistol in his left hand and sat in the doorway of his tent, his finger greasy with sweat on the trigger despite the cold. But you cannot sit alert like that for long after a day of hard uphill walking in the high mountains, no matter how pressing the need. Soon tiredness began to claw its way into the edges of his vision, his head swaying on weary shoulders. But he must not sleep!

The man took pen and paper, and lit a candle. He began to write, sitting at his collapsible camp table, simply for something to concentrate on, something to keep him alert. His left hand still firmly clasped the pistol. The single, lonely light flickered in the high, blank darkness – and the night rolled on. Cold air crept down from the glacier and the snow peaks, and a chill breeze moved through the poplars. The man wrote, on and on, long past midnight.

No one knows what he scribbled in those grim, bleak hours, the pen scratching urgently in a spidery scrawl over the thin blue paper. When it came to making practical accounts of his previous journeys he had been a consummate professional, recording altitudes and route marches with military precision. In other moments he had proven himself capable of penning sharp passages of sarcastic humour, and also of impassioned and unrestrained indignation. Indeed, he had reason to suspect that it was an outburst of the latter that had led him to his precarious vigil on this very mountainside. But whatever it was that he was writing that night, it served its purpose: he did not sleep.

The tone of the darkness deepened; the wind dropped to nothing and the stars faded behind the peaks. Somewhere far to the east, beyond the serried ranks of hills, morning was creeping out of India. But the man had not stopped his writing, nor had he taken his hand away from the revolver. When the morning light reached him, the shapes of the valley formed like a photograph and were clear in the bloodless light before dawn. The high crags were grey and the branches of the trees hung limply in the cool air.

Finally, the man put down his pen and stepped out of the tent. Everything was very still, and where the evening air had carried sounds clearly and sharply, now the distant calls of sheep and goats seemed deadened and muffled. His legs, arms and back ached from sitting on the hard camp chair all night, and hunger gnawed deep in his belly. He shivered, hugging himself in the chill grey air as he glanced about the camp. There was no movement, no sound. No sinister shadows flickered in the trees, no ominous party of tribesmen loitered on the edge of the clearing. Perhaps the danger had passed, or perhaps there had never been any danger at all. The man wondered for a moment whether his long, sleepless vigil had been an outburst of absurd panic over nothing. After all, there had been other occasions when he had openly predicted his own imminent demise and been proved wrong. Whatever the case, it didn’t matter; the night was over and he was exhausted.

Warming yellow sunshine began to seep over the eastern ridges. Squatting down and still shivering, he kindled a small fire and boiled water for tea. He drank it looking out over the valley. Goatherds were beginning to move up the slopes with their flocks, and the noise of the stream was reasserting itself after the false silence of first light. All seemed well, and now the burden of extreme tiredness was weighing ever more heavily; sleep was irresistible. He went back into the tent and lay down, intending to catch a brief rest before starting the day’s journey. Unconsciousness came almost instantly, waves of fatigue sweeping over him as he stretched out, bearing him down into a leaden sleep.

He did not see the single figure creeping across the clearing, flinching expectantly, but growing more confident as no pistol shot came, edging forward, peering into the tent and hurrying away with the news that the Englishman was finally asleep. He did not see the party of armed men in loose, rough clothes hurrying through the trees on the steep slope above the camp, then making their way swiftly, silently, down towards the tent. He did not see one of the Pashtuns challenging the intruders, and so deep was his sleep that he did not wake at the noise of the servant being overpowered.

The first thing he became aware of was a rough hand as it grasped him by the throat. He was dragged upwards from his camp bed, gagging and staggering. Perhaps in those moments of confusion he struggled to remember where he was, and by the time he had come fully to his senses a length of rough rope had been noosed around his neck and his hands were tightly bound behind him. He was dragged outside, blinking and squinting in the hard morning sunlight – for it was already about eight o’clock by now.

They pulled him away across the clearing, stumbling and tripping, and he saw that his servants and munshi had also been captured and bound and dragged off in other directions. As they hauled him uphill to the east, into the dense thicket of trees, he understood the ominous nature of what was happening: they were taking him away from the village, away from witnesses. He had already proved himself a brave man, but this was no time for stoical dignity: he begged; he pleaded with them; he offered to bargain. The captors paid no attention, ducking beneath low branches and hurriedly dragging him deeper into the thicket. They were lean men with fair skin burnt and creased by the harsh mountain climate. They wore twists of coarse turban-cloth or flat, roll-edged felt caps on their heads.

He would pay them off, the man said; they could take everything he had, all the gifts and equipment in the boxes back at his camp. The men scoffed at him. Had he not noticed his current circumstances? All that property was already theirs to take as they pleased. Very well, he said; then he would make sure that a ransom, a huge sum more than they could dream of, would be sent from his own people, the English who ruled India. But the men were not stupid; they knew that this was an empty offer and they paid him no heed. Desperate now, he said that he would send back down the valley to the Kashmiri frontier post at Gilgit; the governor there would provide the money if only they would release him. They were making a terrible mistake. If they would just send for his munshi everything could be arranged.

But they only jeered, enjoying his frantic attempts to bargain.

They were deep in the forest now, a mile from the village, and abruptly they came to a halt. The man stumbled to his knees on the rough ground and one of the captors reached out behind him and tore the ring from the finger of his bound hands. This, quite clearly, was it; the man understood that. And maybe too, in one sharp instant, he understood that he had been moving irresistibly towards this moment for many years, perhaps all his life. He began, desperately, to pray.

They hacked off his head with a sword.

The murderers half-buried the body under a pile of loose rocks, leaving the pale, limp hands sticking out into the mountain air. Then they went back to the clearing, killed the servants and looted the camp.

In the middle years of the nineteenth century it could take a long time for news to seep out of the high mountains west of Gilgit. It was almost a fortnight before word of the death reached the first Kashmiri garrison and began to make its way eastwards towards India, picking up stray threads of conjecture and bazaar gossip in the mountain villages along the way. By the end of August, Kashmir and the towns where the rich Punjabi plains meet the foothills of the Himalayas were rife with rumours that an Englishman had been murdered somewhere in the Hindu Kush. For the British authorities then governing India, this was the worst possible news. Travelling Englishmen were not a common phenomenon in the high mountains beyond the frontier; if the rumour was true then the victim could only be one man – a controversial figure already well known to the government. And if he really had come to grief then his death would prove highly and politically inconvenient, having occurred on the fringes of the territory of the Maharaja of Kashmir.

Of the independent kingdoms (recognising ultimate British suzerainty) that made up much of the British Raj, Kashmir, with its ill-defined and contentious western border, was one of the largest. It was also by far the most strategically important. The maharaja was a difficult man who had to be handled with the most delicate of diplomatic skill. For some years there had been grumblings about his misrule – from both his own subjects and from visiting British citizens – and there had been a good deal of recent controversy about the actions of his troops in the more remote parts of the mountain kingdom. If the rumours of murder proved true they would cause a severe diplomatic headache.

In 1870 the British Raj was approaching its zenith. The ‘Mutiny’ – a bloody uprising by native Indian soldiers in 1857 – had brought to an end the old haphazard empire of the Honourable East India Company. India was now under the rule of the British crown, which covered the patchwork of acquiescent native kingdoms and directly administered territories spanning a huge swathe from the Afghan border to the Bay of Bengal. On the map of the world India was entirely red. There would be no more great wars of conquest in the subcontinent, only border skirmishes and punitive raids.

The British, finding in Indian caste an echo of their own rigid Victorian class system, had established themselves at the very pinnacle of south Asian society. Nowhere, it was said, was an Englishman’s life more sacred than in the subcontinent. In the unthinkable event of a white man’s death at the hands of ‘the natives’, vengeance was essential, a duty in fact, to maintain respect if nothing else. But avenging the lonely death of a footloose Englishman in some wild and inhospitable upland valley beyond the River Indus would prove extremely difficult, no matter how necessary. And if, as the sizzling gossip was now beginning to suggest, the Maharaja of Kashmir himself was implicated in the death, then the connotations could prove catastrophic.

At first the authorities did their best to keep the rumours quiet. The identity of the dead man, obvious as it was, had not been confirmed, and conflicting reports about who was behind the murder were now pouring out of the mountains like spring meltwater. But by the beginning of September the news was so widespread in bazaars and teashops across north-west India that it could no longer be suppressed. On 9 September the viceroy, Lord Mayo, the supreme British authority in India, telegraphed the home government in London telling them of the rumour. The story quickly reached the Fellows of the Royal Geographical Society, for their vice-president, Sir Henry Rawlinson, was also a member of the government’s India Council. As word spread among the venerable old geographers in the oak-panelled chambers of the society’s London headquarters, there would have been a sense of bitter disappointment; they too would quickly have realised who the dead man must be. By the end of the month it was confirmed.

The victim’s identity might now have been known, but little else about the murder was clear. Rumours continued to emerge from the mountains, new twists, assertions and allegations making their way down on to the plains on an almost daily basis. ‘There are some very queer stories afloat,’ wrote the viceroy in a confidential memo. Untangling the threads of misinformation would prove a troublesome task, not least given the remote and evidently hazardous nature of the crime scene. Indeed, the viceroy wondered, if the truth had the potential to prove so politically explosive, might it not be best if the waters remained muddy?

Still, on 3 October, two and a half months after the event, the news was finally made public in the British press: the ‘distinguished traveller’ Mr George Hayward, aged 32, Central Asian explorer par excellence and honoured holder of the Gold Medal of the Royal Geographical Society, was dead, assassinated on his journey to explore the Pamir Steppe.

2

Into the Wild

In the last months of the twentieth century it could still take a long time for news to seep out of the high mountains west of Gilgit – or more precisely, it could still take a long time for news to seep in.

On the morning of 12 October 1999 my father and I stopped to buy some bottled water and snacks from the Gilgit bazaar. The sky hung low and grim, seeming to rest on the jagged peaks of the raw mountains that locked the town into its bowl of grey-brown stone. Gilgit had grown from the lonely outpost of the mid-nineteenth century to become the principal town of Pakistan’s far north, but it was still spectacularly remote. And lying in the belly of the world’s highest mountain ranges, at the very point where the few precarious roads through the Western Himalayas meet, it still had a wild frontier feel. Ominous rifle shots crackled up on the stark slopes above the town from time to time, and the rough and dusty bazaar was full of smuggled goods from China. The faces of the men on the streets – and they were all men – showed that this was the meeting point, the hub of the mountains. There were Baltis with broad, wind-reddened Tibetan faces, and Uighurs and Kirghiz who looked like they had descended from the hordes of Genghis Khan. There were dark, smooth-skinned Punjabis up from the plains; Pashtuns with great beaked noses and hollow cheeks; and here and there a scattering of freckles, a shock of red or blonde hair, and a pair of jade-green or lapis-blue eyes.

We loaded the water and food into the back of the jeep – driven by a large, gentle man of imperturbable calmness named Yusuf Mohammed – and headed west, winding out of town through narrow streets riddled with potholes, overhung with tangles of loose wire and lined with dark, jerry-built shops. The tarmac ran out not far beyond Gilgit, and the electricity cables soon after that. But the grim grey cloud cleared too and we rattled on between stands of tall poplars, copper-coloured by autumn, under an intense blue sky.

Beyond the edge of the mountains in Islamabad, 150 miles to the south, the plates were beginning to shift. Within a few hours events would unfold that would have a dramatic effect on the politics of Pakistan, and on developments in the region in turbulent years to come. But we, making our way along the banks of the Gilgit River towards the Shandur Pass and onwards to Chitral, would hear nothing of it for the next three days. News did indeed travel slowly in those mountains.

I was 18 years old, and a few weeks earlier I had known almost nothing of Pakistan beyond a clutch of vague images of camels and turbans, confused with the more tropical exotica of India. I had only been out of Britain once (a week in Spain two years earlier), and though I desperately wanted to travel I had been brought up on the surfer’s shore of Cornwall and was only interested in tropical places with good waves and beautiful women. I had dawdled through some ill-chosen A-levels and a year of a chef’s apprenticeship, and I was already plotting trips to warm beaches in Bali, Australia and Hawaii. And then, at very short notice, came a completely unexpected chance to join my father for a month in the high mountains of northern Pakistan. It would never, ever have occurred to me to go to such a place – mainly because it was so far from the sea. I knew nothing of south Asian history, had only the vaguest notions about Islam and had never even heard of the Hindu Kush. But now here I was, bouncing around in the back of a stripped-down jeep, waving to village children in the stony fields and heading into the mountains along the same road that the explorer George Hayward took on his own final, fateful journey – though of course, I had never heard of him. It was the most gut-achingly beautiful place I had ever seen.

We spent the first night at Gupis, the very spot where Hayward turned off north into the Yasin Valley. We slept in a government inspection bungalow – a crumbling, British-built cottage of bare rooms and creaking furniture kept by an ancient, doddering caretaker. He slaughtered a chicken for our dinner, wringing its neck in the garden and half-muttering a prayer to make it halal, and we sat eating by lamplight in the humming darkness.

The next day we continued towards Shandur (leaving Hayward behind at the junction of Yasin). The road was rougher and wilder, and the country around us all the more stunning. The track followed the southern flank of a long valley, walled in by soaring snow-peaks. There were villages where small children with sun-burnished hair ran cheering after the jeep and women in embroidered blue skullcaps watched us shyly from the fields. Little terraces of winter wheat lined the hillsides and the streams and watercourses were marked by stands of willow and poplar, turning to intense metallic reds and golds in the fading year. The sky was a brilliant aquamarine, and the river, bouncing and tumbling over boulders, matched its colour. Above us the barren mountainsides were dusted with new snow. It was cold at night, but in the daytime you could still feel the warmth of the sun pressing on the back of your neck.

In Islamabad political hell had broken loose, but there was no television and no radio up here, and as we stopped for a second night in another dusty inspection bungalow at Phundar, looking out over the higher reaches of the valley, we knew nothing about it.

It was difficult to imagine a more wonderfully remote place. The next day we crossed the high watershed of the Shandur Pass, a broad, grassy saddle flanked by sharp peaks and scoured by a biting wind, and began to drop into the northern fringes of the North-West Frontier province. The mountains were taller and rougher here, and the valleys more ragged and stark. We rolled back on to cracked tarmac at dusk and came to the mountain bazaar of Chitral, a wild-edged township in a locked valley, long after dark.

The next morning, from a scruffy little office in the market, we called home on a crackling line. My mother, understandably, was concerned for our safety, worried that we had been caught up in recent events. We were at first puzzled, then startled, then finally highly amused as she explained – from a Cornish farmhouse thousands of miles away – that during our journey from Gilgit to Chitral the Government of Pakistan had been overthrown in a dramatic military coup. And we had known nothing about it.

In 1999 Pakistan was coming to the end of one of its occasional unhappy experiments with civilian democracy. As often seems to be the case with these periods, government corruption had reached orgiastic levels, and the nation’s only consistently stable institution, the army, was beginning to grumble. The incumbent prime minister, Nawaz Sharif, and the then leader of the opposition, Benazir Bhutto, had spent the 1990s trading periods of inept and woefully corrupt government. Nervously aware of Pakistan’s military default mode, on 12 October 1999 Sharif decided to dismiss the head of the army, Pervez Musharraf, while he was out of the country at a conference in Sri Lanka, replacing him with a tame general of his own choosing. Musharraf – an oddly earnest little man of a rather different mould from the bristling Sandhurst style of most south Asian generals – leapt aboard a commercial flight home while battalions across the country turned rapidly against the civilian government.

Desperate to keep Musharraf at arm’s length, Nawaz Sharif ordered his plane diverted to a remote desert outpost. The plane – full of civilian passengers – circled; but air traffic controllers under Sharif’s orders refused permission to land and fuel supplies dwindled. In response the army came on to the streets of Karachi, the airport was seized, and Musharraf touched down with, it was said, only seven minutes’ worth of fuel to spare. Nawaz Sharif was later charged with hijacking. Meanwhile, in Islamabad, those civilian politicians who had any sense were busily shredding documents, disguising themselves as women and bolting over the garden wall. By the time my father and I reached Chitral late on 14 October Pakistan was, for the third time in its fifty-year history, a military dictatorship.

Because of these events, and because of the place where we had been so blissfully unaware of them, I came to associate the high mountains between Gilgit and Chitral with momentous happenings long before I knew anything of Victorian geopolitics, George Hayward and the Great Game.

When we left Pakistan at the end of October I was immensely impressed and grateful to have seen such a staggeringly beautiful place. But as the battered black and yellow taxi carried us through the morning rush hour to Islamabad airport I distinctly remember thinking that it was unlikely that I would ever return.

Three months later I was back on my appointed path, on the north shore of Oahu, Hawaii. It was hot and humid, the water was warm, the surf was good and there were palm trees and women in tiny bikinis. But each evening after I had made my barefooted way back to the hostel, sunburnt and shaken by the monstrous waves of the north Pacific, I lay reading on my sand-scattered bunk. The books I read were not of surf and sunshine, but of the high mountains of Asia and of journeys made there by Nick Danziger and Wilfred Thesiger.

The next September I was back in Pakistan, alone this time, dressed in a pakol and shalwaar kamis, and travelling by the cheapest means possible. The dusty backpack that I slung on to bus roofs and lugged through seething bazaars was full of books. They were books of history and adventure, and I consumed them as hungrily as I consumed the kebabs and karahis from the chaikhannas where I ate. I read travel classics; I read of the violence of the partition of the subcontinent; of the trauma of Kashmir; of the mujahidin war against the Soviets in Afghanistan; and of epic mountaineering expeditions. But above all I read of the Europeans in the nineteenth century who had travelled in the mountains which now belong to Pakistan and the central Asian states. They were wildly romantic figures. Men who were half-explorer, half-spy, travelling incognito and meeting grisly ends among hostile tribes. Or bringing back explosive news of new passes, valleys and ranges – all of them were players of the Great Game.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century some 2,000 miles of mountains, deserts and unstable Muslim potentates separated Britain’s Indian territories from the southern frontier of the Russian Empire. A hundred years later these same borders were only a few miles apart (just beyond the very pass that Hayward had been trying to cross when he was murdered). The Great Game was the cold war of intrigue, exploration and exploitation that the two mighty empires played for a century or more in the turbulent and ever contracting space between.

For much of the nineteenth century the political classes of Britain – particularly those involved with India – were obsessed with ‘the Russian Threat’ in a way that makes today’s fretting about ‘al Qaeda’ terrorism seem petty by comparison. It was Napoleon Bonaparte who started it off. In 1807, at the height of his pan-European rampage – and before he developed his own designs on Russia – the diminutive Corsican had suggested to Tsar Alexander I a joint Franco-Russian project to invade India and wrest it from nascent British control. India, with its impenetrable mysteries and untold riches, had always been the ‘jewel in the crown’ for would-be expansionists from the north and west. In voicing this ambition Napoleon was following a tradition that ran back at least as far as Alexander the Great. But in the early nineteenth century they were entering the modern era of global geopolitics. The British got wind of the plot with its talk of troops sweeping through the Khyber Pass – and went berserk, prompting a hysterical diplomatic crisis.

The planned invasion came to nothing of course. It was wildly impractical and beyond even Napoleon’s mighty capabilities. But the damage was done: the idea of an invasion of India from the north was firmly planted in the British consciousness, and in popular and political imagination the Russian Threat loomed over the buxom bounties of the Raj like a rapacious Cossack raider for the rest of the century. And as Britain’s Indian empire expanded ever westwards – from its initial tenuous toehold of mud, malaria and warehouses on the Ganges Delta to take in Sind, then the Punjab, and finally to nudge up against the fringes of Afghanistan – events in such outlandish places as Samarkand, Kashgar and Chitral were no longer the irrelevancies they had once been. The Game was in play.

The term ‘Great Game’ was coined by a British explorer who eventually met a sticky end at the hands of the Emir of Bokhara in modern-day Uzbekistan, but it was popularised by that laureate of empire, Rudyard Kipling. It was the coldest of cold wars – often quite literally so, in the icy heights of the Western Himalayas. There were no military engagements between British and Russian troops; players from the two sides only ever came face to face in the wilds of Central Asia on a handful of occasions. In fact, there was very little large-scale military action at all. The Great Game was instead a phenomenon where minor skirmishes in remote mountain fiefdoms took on towering significance, and where a border incursion by a small party of wandering Cossacks could provoke a full-scale diplomatic incident. It was a ‘tournament of shadows’ played out, for the most part, by individuals, spies, mercenaries and men who would be king.

For much of the nineteenth century the portion of the great Eurasian landmass to the north-west of India was one of the least known parts of the planet. There were other white spaces on the map of the world of course, but those were empty deserts or dense jungles. What made the lack of knowledge about Central Asia so startling was that this was no uninhabited wasteland: there were great cities out there, place names known since antiquity. Even beyond the middle decades of the century European geographers still had no idea where on the map to place significant caravan towns like Yarkand, and few of the major rivers of India had been traced to their source. They had hardly even begun to untangle the monstrous mountain knot centred on Gilgit, where the world’s highest ranges lock together like the fingers of a clasped pair of hands, and when it came to the Pamirs, no one was even sure if they were a plateau or a mountain range.

It was an area crying out to be explored, and there were plenty of adventurers willing to try. But never has the boundary between scientific exploration and politics been so blurred. Many of the men who explored the region – and they were all men – were private individuals; few of them went on overt official duty, but none of them were impartial, and the news, maps and observations that they brought back to India were of the greatest significance. Was there evidence of Russia meddling in the affairs of remote Muslim kingdoms? Were goods made in Moscow flooding the bazaars of the old Silk Road? And perhaps most importantly of all, was there somewhere a chink in India’s Himalayan armour, some gap in the mountains through which an invading northern army could flow?

To anyone who has seen the wildly rugged and inhospitable mountain terrain of the subcontinent’s north-west corner, the idea that a full-scale military invasion could sweep down upon an unsuspecting India by way of one of those windswept passes may seem ridiculous. This does highlight something that needs to be said about the Great Game. For years most writers and historians have approached the subject from a starting point of accepting that the Russian Threat was very real and that Central Asian geopolitics was a deadly serious affair. In recent years, with the ‘post 9/11’ war in Afghanistan and the jostling for oil and gas rights in the former Soviet states around the Caspian Sea, there has been a good deal of chatter from commentators about ‘the new Great Game’. Indeed, there are some who argue that the old Great Game never really went away. They point triumphantly to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 as irrefutable evidence that while the British Raj may have long since faded from the scene, expansionist Russian designs on the subcontinent have never faltered.

All that aside, few would argue that the Great Game was not taken very seriously during the nineteenth century. However, some modern historians, particularly those from India and Pakistan, convincingly argue that the whole Great Game was just that – an act, a sham – and that the Russian Threat was a deliberately constructed myth. No Cossacks, they say, were ever going to sweep down the Khyber Pass to seize India. But in a piece of textbook neo-conservative thinking – long before George W. Bush rolled into Iraq in search of weapons of mass destruction – the idea that they might do just that was deliberately encouraged, inflamed and instilled in the minds of the British public purely to justify expansionist colonial policies. As Britain’s Indian armies clawed their way deeper and deeper into the mountain territory beyond the subcontinent’s natural boundary at the Indus River, usurping and subjugating more and more little independent states, it could all be justified with a single phrase: the Russian Threat. That the threat was a myth was beside the point. And away to the north, these historians say, the Russians were up to the very same tricks, encouraging alarm at imaginary British influence spreading through the khanates and kingdoms of Central Asia to justify their own forward push. It is a convincing argument.

Even if it was just a game, however, even if the Russian Threat was imaginary, those who played did so in earnest. And what a motley crew they were! There were the inevitable imperial archetypes, all bristling moustaches and stiff upper lips, but they found themselves in very mixed company. Amongst those whose travels could loosely be classed under the terms of the Great Game was Joseph Wolff, a rampaging German convert to Anglicanism who marched about Central Asia on mercy missions, searching for Jews to Christianise, refusing to tell a lie and referring to himself in the third person. There was the pompous philanderer Sir Alexander Burnes, whose penchant for Afghan women was notorious and who met his end at the hands of a Kabul mob (his womanising was the least of their complaints). The first foreigner to record a visit to Gilgit was the almost inconceivably self-important Dr Gottlieb Leitner: ‘M.A., Ph.D., LL.D., D.O.L, etc’ (what do all those letters stand for and how could anyone be so pompous as to write etcetera after their name?). Another German, he spoke thirty-odd languages, collected a spectacular human zoo of mountain folk at his Lahore headquarters, built one of the first mosques in England and turned up in Gilgit with nothing but three jars of Bovril in his pockets. And then, of course, there was the mighty Sir Francis Younghusband, a man with a magnificent moustache and an expression of permanent bemusement. He started out as a doyen of imperialism but ended his days as some kind of bizarre proto-hippie, raving from his armchair about eastern mysticism and extraterrestrials. And there were countless others, some brave and professional, some cheating charlatans, some downright crazy.

As I learnt more and more about these glorious characters, one always caught my imagination. He seemed to loiter a little way beyond the fringes of the crowd, a little out of place, a little out of time. Perhaps it is no coincidence that he was one of the most shadowy of all the Great Game figures: his origins were, until recently, a mystery; the real reason for his death is likely to remain so. While the likes of Leitner and Younghusband churned out books of travels faster than most people can read, this man left scant traces: a letter here, a report there. But for all this elusiveness there was something that shone through, something that always caught my attention. His brutal unsolved murder alone was intriguing enough, but there was more: he seemed to exude a strange intensity, setting him apart, latching him deep into my imagination. His name was George Hayward.

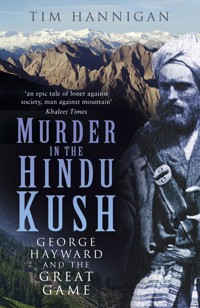

There is only one known photograph of George J.W. Hayward, and it is striking. Other Great Gamers appear in their ‘native garb’ in contrived studio portraits – robes worn self-consciously, turban cocked at a jaunty angle above pouting lips and a trembling moustache. The adventurer is perhaps flanked by a pair of fragrant Asiatic youths, and it all has an air of fancy dress and high camp. Looking like that it is hard to imagine that they ever managed to pass themselves off as Afghan horse-traders or Bokhariot pilgrims; they seem more like bit players in a Christmas pantomime. But the picture of Hayward is very different. It is a staged shot, and Hayward is in native dress, but there is nothing arch or silly about it.

The photograph is undated, the photographer unknown and the location unidentified, but given the setting and the circumstances it seems almost certain than it was taken in Kashmir in early summer 1870, during the final turbulent months of Hayward’s life. The explorer stands centre stage in the garden of some rather neglected building of columns and arches with his back to the pitted, gnarled trunk of a huge tree. Clear upland sunlight streams in from the right.

The costume he is wearing is thought to be that of the Yasin Valley, the very place in which he died. His robe is of dark, coarse cloth, stiff with the grime of travel; you can almost feel it itching against your own skin. A long, curved sword is tucked into his belt, and he holds a heavy, studded shield in his left hand while his right clasps tightly at the shaft of a spear. A turban of off-white cloth is loosely bound around his head. At his feet, arranged in a great semicircle, are the huge, claw-like horns, some still attached to flyblown heads, of half a dozen enormous wild goats – the ibex and markhor he had bagged on an earlier journey – while at the very right of the frame sits a native in a sloppily tied turban, looking more villainous than fragrant. And armed to the teeth, standing proud between classical columns and decapitated cloven-hoofed beasts, Hayward himself looks more like some Greek god of carnage than a foppish Victorian dandy.

It could, of course, be a moment of indulgent dressing-up, but it doesn’t look like it: Hayward isn’t grinning or mugging for the camera. In fact, it is his expression that is most arresting. His face is gaunt, fringed by a thick, blondish beard. His nose is long and slightly crooked, and buried under a heavy moustache you can just detect a firmly set mouth. But it is the eyes that have it. Beneath a broad, high brow, pinched into a frown of utter seriousness, they glare away to the right of the camera from dark, intense hollows. There is nothing jaunty or jolly about him and setting out into the hills with such a man would be an alarming prospect. As one writer put it, ‘He looks a most unsettling companion.’

Hayward was in some ways the epitome of the Great Game’s shadowy nature, of exploration mixed with politics, but in other ways he was completely at odds with the gentleman’s rules by which the game was played, choosing to make himself a permanent outsider, gathering no real friends and alienating people. His lonely death that bright July morning proved that. Some have chosen to see him as a suicidal fool, driven by a death wish; for others he was a man possessed, so consumed by his urge to reach his destination – the High Pamirs – that he became oblivious to the dangers. Still others regard him merely as a remarkably dedicated professional explorer who died in the line of duty, always seeking to further geographical knowledge no matter how challenging the circumstances. Perhaps he was all those things, and more.

He was certainly unusual. He appeared on the exploration scene from nowhere and launched himself on a mercurial career. He was one of the first two Englishmen to reach the fabled bazaar towns of Yarkand and Kashgar on the southern edge of the Taklamakan Desert; he crossed, measured and mapped numerous new passes along the Himalayan watershed and traced the source of a major Asian river. He pushed further west from Kashmir than any European had done before, and he performed staggering feats of endurance, making some of the nineteenth century’s most audacious winter journeys in the Western Himalayas. He blazed brightly through the mountains for two years, and then, abruptly, was gone.

His death in that bleak valley provoked outrage in polite Victorian society. Of course it did: the death of any Englishman in such a place, at the hands of such people would. Various allegedly first-hand accounts of the murder eventually emerged into the public arena. One of these was later bowdlerised and bastardised by the poet Sir Henry Newbolt, school chum of Francis Younghusband and quivering champion in rhyming doggerel of public school values, imperialism and honourable deaths (‘Play up! play up! and play the game!’). His version of Hayward’s murder, He fell among Thieves, is excruciating and infuriating:

‘Ye have robb’d,’ said he, ‘ye have slaughter’d and made an end,

Take your ill-got plunder and bury the dead:

What will ye more of your guest and sometime friend?’

‘Blood for our blood,’ they said.

He laugh’d: ‘If one may settle the score for five,

I am ready; but let the reckoning stand till day:

I have loved the sunlight dearly as any alive.’

‘You shall die at dawn,’ said they.

He flung his empty revolver down the slope,

He climb’d alone to the Eastward edge of the trees;

All night long in a dream untroubled of hope

He brooded, clasping his knees.

He did not hear the monotonous roar that fills

The ravine where the Yassin river sullenly flows;

He did not see the starlight on the Laspur hills,

Or the far Afghan snows.

He saw the April noon on his books aglow,

The wisteria trailing in at the window wide;

He heard his father’s voice from the terrace below

Calling him down to ride.

He saw the grey little church across the park,

The mounds that hid the loved and honour’d dead;

The Norman arch, the chancel softly dark,

The brasses black and red.

He saw the School Close, sunny and green,

The runner beside him, the stand by the parapet wall,

The distant tape, and the crowd roaring between,

His own name over all.

He saw the dark wainscot and timber’d roof,

The long tables, and the faces merry and keen;

The College Eight and their trainer dining aloof,

The Dons on their dais serene.

He watch’d the liner’s stem ploughing the foam,

He felt her trembling speed and the thrash of her screw;

He heard the passenger’s voices talking of home,

He saw the flag she flew.

And now it was dawn. He rose strong on his feet,

And strode to his ruin’d camp beneath the wood;

He drank the breath of the morning cool and sweet:

His murderers round him stood.

Light on the Laspur hills was broadening fast,

The blood-red snow-peaks chill’d to a dazzling white;

He turn’d, and saw the golden circle at last,

Cut by the Eastern height.

‘O glorious Life, Who dwellest in earth and sun,

I have lived, I praise and adore Thee.’

A sword swept.

Over the pass the voices one by one

Faded, and the hill slept.

Clearly Newbolt had never been to the Yasin Valley. And clearly he knew nothing about death by beheading.

I once had the misfortune to see grainy video footage of one of the wretched hostages being beheaded in Iraq. Some person of limited intelligence and deficient compassion had downloaded it on to their mobile phone and, grinning inanely, thrust it under my nose. The horrible scene had played out before I realised what I was watching, but the gurgling, the spasms, the twitching and flinching, stayed with me for days afterwards. This is exactly how Hayward would have died. One of the contemporary accounts speaks of how the assassins ‘hacked off his head after the half-hacking, half-sawing way they have of killing sheep in the Himalaya’. There was no poetically smooth single stroke of a shimmering blade; Hayward’s death would have been brutal, messy and unimaginably horrific.

But if wishful thinking and an urge to romanticise a thoroughly unpleasant murder is perhaps excusable, the attempt to co-opt Hayward into a rosy image of Little England, with cricket, warm beer and nuns on bicycles, is outrageous. This kind of nonsense was Newbolt’s stock in trade – all foreign fields and Union Jacks – but he did Hayward a massive disservice by turning him into the perfect, straight-backed Englishman. He was nothing of the kind. He left school at 15 and knew nothing of college eights and serene dons. If he was dreaming of anywhere in his last, violent moments it would have been the bleak heights of the Pamirs, not some quaint Home Counties village.

For this is at the very heart of what attracted me to Hayward: there was something about him, something in that raw intensity, that was palpably un-Victorian, un-British. Other Great Game explorers headed into the wilds of High Asia with armies of servants, literally tons of supplies wobbling along after them over the passes on the backs of yaks and mules. They took vast stocks of books and surveying gear, and complained when their bottles of claret cracked in the sub-zero temperatures. Hayward travelled hard and light, alone or with just a couple of servants. He often dispensed with even the most basic of equipment, carrying no tent, and sleeping through blizzards in the lee of overhanging boulders. Where other travellers excelled in the flowery arts of diplomacy in the exotic courts that they visited, Hayward proved wantonly, wilfully inept, failing to follow correct etiquette and offending all and sundry. But this does not seem like straightforward arrogance; it has more to do with that same unstable intensity. And if the most English of traits is to keep quiet, not to rock the boat or make a fuss, then Hayward was anything but English. I’m inclined to suspect that he would have found Newbolt’s poem deeply offensive.1

By the time I left Pakistan that second time, Hayward, his brief, shadowy life, and his brutal, mysterious death, were firmly implanted in my imagination. Without realising I was doing it I sought him out elsewhere, held up others to see if they matched his standards – and found them wanting. Over the years I read of other travellers and other explorers – both of nineteenth-century Asia and beyond. Many were more dramatic, more distinct and more endearing than George Hayward, but somehow none of them matched that sizzling intensity.

Many of the Victorians were almost clown-like despite their unmistakeable bravery. Burton and the other pioneers of Africa certainly came from that eminently risible mould – but not Hayward. In the traces he left I saw none of the self-indulgent Orientalist romanticism of T. E. Lawrence or Wilfred Thesiger (and none of their aristocratic sexual confusion either). Classical Arab travellers like Mas’udi and Ibn Battutah displayed a fey dreaminess at odds with Hayward’s hard-headed practicality, and he demonstrated none of the slick – and occasionally irksome – self-deprecation of the best twentieth-century travel writers. Nowhere else did I see that indefinable but unmistakably intense aura replicated, but I did once catch a faint echo of it. It came in the most unexpected of places: the Alaskan backwoods of the late twentieth century.

On 6 September 1992 the emaciated body of a young American backpacker named Chris McCandless was found in the forest north of Anchorage. He came from a middle-class background in the tame suburbs of Washington DC, but for the two years before his death he had been hitchhiking back and forth across the empty spaces of the American West, leaving a patchy, elusive trail. His story was made famous by the writer Jon Krakauer in his book Into the Wild, later made into a Hollywood movie.

Krakauer chose to romanticise McCandless, painting him as the embodiment of some raw American frontier spirit. Others – myself included

– saw things rather differently: he was a naïve and self-indulgent city boy, ill-equipped for the Alaskan wilderness. He starved to death in an abandoned bus only a day’s walk from the nearest surfaced road. In this respect he is but a flea on the hem of George Hayward’s travel-stained Afghan robe, but still, there was something about McCandless that instantly reminded me of Hayward. Perhaps it was that determined rejection of the mainstream, that self-induced sense of otherness, that intensity. He too, I imagine, would have been an unsettling travelling companion.

Of all the written scraps and fragments that George Hayward left, the most famous, and that given the most significance by those who have tried to understand him, was a bleakly sarcastic passage of prescience. He scribbled it during a period of miserable imprisonment in the Silk Route city of Kashgar, sketching out future careers for himself and another travelling Englishman held in the same town. His counterpart, he predicted, would go on to lionised greatness, a hero of travel and exploration, feted, wined and dined by polite British society. Meanwhile, ‘In contradistinction to all this,’ Hayward wrote, ‘I shall wander about the wilds of Central Asia, still possessed with an insane desire to try the effects of cold steel across my throat.’

From anyone else this could be dismissed as empty Victorian bravado, but not from Hayward. Given the circumstances in which the note was written, the ‘cold steel’ part – prophetic as it turned out to be – could be viewed as silly hyperbole, but something about the ‘insane desire’ rings true. For there did seem to be some strange spark in him. Desire certainly, insanity perhaps, but whatever it was it drove him on, deeper and deeper into the mountains, further and further from home. In that, and in that alone, I sensed that he had a kindred spirit in the unfortunate hitchhiker Chris McCandless.

From my starting point in the high mountains of northern Pakistan, I travelled onwards, propelled by conventional wanderlust rather than some ‘insane desire’. To the south I explored the rest of the subcontinent, from the cape of Kanyakumari to the backwaters of Bangladesh. Northwards I made my way across China from west to east. I turned through the cities of the Middle East and along north African shores, and I drifted off between the islands of South-East Asia.

My reading and historical interests followed these extended, low-budget holidays. From the Great Game I journeyed into the wider story of the British Raj and its demise, and of European colonialism in general. India and Hinduism led me south-east to Indonesia and old Indochina; in the other direction Islam took me away towards Middle Eastern history and politics. But always the threads, the lines of communication, led back to that chaos of high mountains where the frayed borders of modern-day India, China and Pakistan break down and come apart amongst glaciers and ridges.

Looking at the map of Asia it is easy to see why: that crowded space, centred on Gilgit, really is the hub of the entire continent. Great mountain ranges sweep away in all directions from the tangled core. To the east the main Himalayan chain dips, swells and bursts into the great purple bruise of the Tibetan Plateau, with the Kun Lun bearing in from the north and the jagged splinter of the Karakoram buried between. From the north-east the Tien Shan, the Heavenly Mountain Range, rises ice-white and glittering over cold deserts and empty steppes, and arcs in to the meeting point. At its base squats the Pamirs, barren and desolate. And from the south-west, bearing inwards from the Desert of Hell and bones of Afghanistan – like the infinite branches of some vast tree – comes the Hindu Kush, the Killer of Hindus.2

I might be elsewhere; I might be in steamy jungles or on coral shores, or indeed in dreary English suburbia, but somewhere in the back of my imagination that mountain knot remained. And if I looked carefully, moving through it, flickering, elusive, enigmatic and intense, disappearing, coming back into view, pushing ever onwards, possessed with an insane desire, was the figure of George Hayward.

Between long bouts of travelling and hot summers plying my sweaty chef’s trade in Cornish restaurant kitchens, I stumbled in fits, starts and deferments through a journalism degree, lived for a year in Indonesia and spent every penny I ever earned on cheap flights and third-class train tickets. Before I knew it a decade had passed: ten years since 12 October 1999. I felt that I needed to do something to mark the passing of that decade. It was time, I decided, to hunt down George Hayward, to gather together whatever there was to be known about him, and to follow him on his journeys – even all the way to the location of that lonely death.

Notes

1 It is hard not to suspect that Hayward would also have been offended – but perhaps for other reasons – by the 2007 stage play, The Great Game. Written by an American playwright, in it he is glibly recast as a British aristocrat who marries a one-eyed Indian proto-feminist to the horror of his upper-crust parents (he wasn’t; he didn’t; he was an orphan).

2The whole, monstrous mass of jumbled rock and ice at the north-west corner of the Indian subcontinent is sometimes known – in an attempt to simplify and make sense of it – as the Western Himalayas. I will use the term here when talking in general about the vast mountain body. When talking about a more specific range or area I will use the individual names, such as the Hindu Kush, the Karakoram or the true Himalaya.