6,86 €

Mehr erfahren.

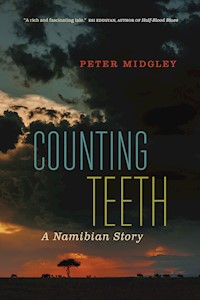

- Herausgeber: Wolsak and Wynn

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

With his nineteen-year-old daughter, a collection of maps and the help of an opinionated GPS, Peter Midgley sets out across Namibia. Visiting small-town museums and gravesites, crossing border checkpoints and changing tires, they travel its length and breadth. Stories about Portuguese explorers and the first genocide of the twentieth century collect on the back seat of their car alongside the author's earliest childhood memories of growing up in the country. By the end of the journey, the stories piece together into an understanding of Namibia's present and make it possible for Midgley to share his love for this complicated, vibrant place with his daughter.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 463

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

ABOUT THIS BOOK

With his nineteen-year-old daughter, a collection of maps and the help of an opinionated GPS, Peter Midgley sets out across Namibia. Visiting small-town museums and gravesites, crossing border checkpoints and changing tires, they travel its length and breadth. Stories about Portuguese explorers and the first genocide of the twentieth century collect on the back seat of their car alongside the author’s earliest childhood memories of growing up in the country. By the end of the journey, the stories piece together into an understanding of Namibia’s present and make it possible for Midgley to share his love for this complicated, vibrant place with his daughter.

OTHER BOOKS BY PETER MIDGLEY

perhaps i should / miskien moet ek

B for Bullfrog

Vusi’s Long Wait, 2 ed.

For my daughters, who at different times have shared Namibia with me.

“The death rattle of the dying and the shrieks of the mad . . . they echo in the sublime stillness of infinity.”

– Unknown German soldier, recalling the

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Acknowledgements

Abbreviations

Terminology

Glossary

About the Author

Copyright Information

1990

“So Whitey, what can you tell us about revolutions?”

The past few days were a blur. Four days earlier, on Thursday, I had been walking along High Street in Grahamstown, a small South African university town. A single thought occupied my mind as I made my way toward the university: the government had refused to grant me further exemption from conscription, and I was due to report for military service in three days’ time. In front of the Drostdy Arch, which divides the campus from the city, Andrew Roos stopped me to ask whether I’d heard about the job in Windhoek. I hadn’t. From the Drostdy Arch, I walked straight to my department and faxed in a resume. That afternoon, I had my interview by phone.

On Friday, I packed. On Saturday morning, the day I was meant to report to base, I said my goodbyes to Julie and our daughter, Andreya, and boarded an airplane to Windhoek to lecture Afrikaans at the University of Namibia. It was well after midnight when I fell into bed.

Although I was barely five years old when our family had left Namibia – Dad, a bank manager, had been transferred back to South Africa – the country remained an integral part of my life. It was the fabric that enveloped our family; it was a place of imagination. In our home, any mention of Namibia was filled with love and longing. We returned there for holidays and we welcomed friends and family who still lived there. Always, there were stories: the ones Ma shared and the ones visitors brought with them. The art and artifacts that filled our house came from there. Every photo album was filled with pictures of our time in Namibia. In the narrow alley between the house and the garage, a set of kudu horns grinned at me every time I went to get the lawnmower. Over the years, the teeth and horns had been loosened by decay, yet it remained there in the alley – a reminder of a trip to Namibia. When other children at school chose to do school projects about faraway places like Japan, I had chosen Namibia.

I woke early on Sunday morning, still exhausted from travel, but I couldn’t sleep any longer. I opened the curtains and watched the sun rise over the Auas Valley on my first day back in Windhoek in almost twenty years.

I was home.

Later that morning, I had lunch with my new colleagues. I returned with a pile of books and began to prepare for my first classes. At nine o’ clock on Monday morning, I introduced myself to the students taking a course called Literature and Revolution.

I am no longer sure who asked the question. The more I think about it, the more convinced I am that it was Freddie Philander, a large, imposing man with a deep voice and greying temples. If I close my eyes, I can still see him about two-thirds of the way up the lecture theatre, near the centre of the row, leaning forward with an air of confidence that unsettled me. Memory can play tricks on one’s mind, so I could be wrong about Freddie. In the end, it doesn’t really matter. What matters is how a question like that sears itself into your mind. That, and how you respond. I froze.

A handful of students chuckled at the sight of an inexperienced young lecturer standing there met ’n bek vol tande, as the Afrikaans expression goes – with a mouthful of teeth. Lost for words. It was the first class I had ever taught and two minutes into it, I was floundering. I searched desperately for something to say, but all I could see in my mind’s eye was the grins on their faces and I knew with absolute certainty that the rows of teeth were multiplying as they prepared to devour me. And yet it seemed appropriate, for teeth and Namibia had always gone hand-in-hand for me. Well, if truth be told, it was more like teeth-in-hand that went with Namibia. I had lost my front teeth falling down the stairs as a toddler in Okahandja and they didn’t return for many years. While my teeth went AWOL, my mother could remove hers at will, although she always assured me it happened by accident. Ma was sitting in the corner chair, crocheting and talking. I sat on the floor beside her taking in the adult conversation. “Uit!” Ma said after a while. “Jy’t genoeg tande getel. Loop speel.” Out. You’ve counted enough teeth now. Go play.

I scurried out, but soon snuck back inside and hid behind the couch that divided the lounge and the dining room. From there, I could take in the conversation undetected through the latticed stump of the Owambo stool. Inevitably, conversation turned to Namibia, the land of milk and stories you could chew on for hours as if they were a nice piece of biltong. Ma’s story meandered and just at the moment where things became interesting, she reached forward to get a chocolate from the bowl on the coffee table.

While we all waited for her to pick up her narrative, Ma closed her eyes, put the chocolate into her mouth and bit down. The whip-crack echoed across the lounge and the story ended abruptly. Slowly, Ma pulled the chocolate, and her front teeth, from her mouth. Four perfect incisors astride a chunk of chocolate-coated crème caramel. Dad was at her side within seconds, brandishing a tube of Bostik.

“As good as new!” he announced proudly as he pulled the set of uppers from the vice half an hour later. Ma just glowered at him and waited for the dentist to call her back. But I did notice that she slid the old set that Dad had repaired into the drawer by her bedside. She had lived through the Second World War and had learned not to throw away anything that might still be useful.

I dusted off the memory and put it aside. Slowly, I removed the proverbial teeth from my mouth so that I could speak. I was formulating a response to Freddie’s question on the fly, but as I spoke, I knew that, once more, I was counting teeth – listening in on a conversation that was way beyond my comprehension, searching for some Bostik to mend the crack that had opened between us. No matter how hard I tried, my theoretical knowledge would never match the practical reality of these students, several of whom were demobbed soldiers who had only recently returned from exile after the twenty-five-year War of Independence.

“I doubt I can teach you anything about revolutions,” I said, “but I may have something to say about literature.”

At the end of that class, one of the students, Mr. Huiseb, came to the front to talk to me. He leaned against the lectern and ran his fingers through the thick mat of his beard as I collected my notes. Then, just as I slipped everything into my briefcase, he asked, “Do you have a passport?”

“No,” I said, for I knew he meant a Namibian passport. Other passports were easy to come by, but very few people had passports for a country that, technically, did not yet exist.

“Every Namibian needs a passport. You are a Namibian, therefore you need a passport. Come.” He drove me to the temporary passport offices in Klein Windhoek and waited for me to collect the necessary forms.

“What brought you back?” he asked me on the way home.

“Independence. And the South African Army.”

“Ah, yes, the army. Well, the passport will help.”

I understood. As a documented citizen of a foreign country, I could no longer be conscripted. But it went deeper than that. A Namibian passport meant I belonged here. It was the first step toward becoming part of a nation.

Independence Day came and went in a flurry of flags and festivities. My Namibian identity documents arrived in the midst of the festivities, but I barely noticed, for there were more important things to celebrate. After a week of feasting, we went back to work and life returned to normal. The following week, at the end of March, Julie and Andreya joined me in Windhoek and we got married. The euphoria of independence dragged on throughout the year. By day, we worked hard at making our new democracy work. Sometimes it did and sometimes it didn’t, but always we tried. In the evening and over weekends, we found reasons to celebrate the return of friends from exile, or toasted achievements like a successful play or a new book by a Namibian author. Too soon, the year was over and my contract had expired. It was time to move again, back to South Africa, which by then was also tottering toward freedom.

August 2011

From the minute I step out of the plane and walk onto the tarmac toward the customs building with my daughter, I know I love this place. We cross the tarmac and enter the shade of the terminal building. The woman at customs examines my papers carefully. “Why do you have this passport?”

“Because I am a South African citizen?”

“Yes, but it says you were born in Okahandja. Why don’t you have a Namibian passport?”

There are people queueing up behind us and I try to keep my response simple. “It was stolen.”

It’s the truth. Shortly after Julie, Andreya and I had returned to South Africa, someone broke into our car and stole my briefcase, which had my passport in it. I tried to get a replacement right away, but the Namibian officials were adamant that I had to apply in person in Windhoek. With each passing year, the chances of getting a new passport seemed more remote. By the time we moved to Canada, I had given up on my Namibian passport, but Namibia followed me across the ocean, just as it had followed me on road trips throughout my childhood. The road to Port St. Johns was filled with stories of the time we travelled to Swakopmund; the trip down to East London was about the time we drove through the Namib Desert. Any dirt road on the way to a farm would remind Ma and Dad of something Namibian. And yet, although these stories filled my life, I knew many of them only as words that accompanied photographs and from a collective family memory, for at the time I was still too young to recall more than fragments on my own and I longed for my own Namibian experiences and for something tangible to tie me to the country I’d always considered home.

Try as I might, I cannot recall Ma and Dad ever looking at a map because the names of places were so ingrained in their minds. Somehow, they just seemed to know which road to take. And they remembered where they’d been. They knew each place and in each town, behind every Karoo bush and every camelthorn tree, they had a connection. And always, Ma had a story to tell. Every tale she told meandered until it returned, safe and complete, to where we had started: in Namibia. Ma could make a story loop out across the veld like an ox whip before she tugged at the handle and let the tale double back and crack to a conclusion. But until then, her stories would bend and twist and prod us toward our destination until we fell asleep, exhausted, and dreamed of Namibia.

After we had returned home from holidays at the beach, we would unpack the driftwood of our days at the florist shop, where Ma could give these gifts of the sea new life in her arrangements. Then we would manoeuvre the caravan into a corner in the backyard, where it rested until it was called to duty again. When the memory of the trip had receded somewhat, I would take the key, the one with the cloverleaf head and the faded woven leather tassel attached to it, and walk to the caravan to pry open those memories once more and give them a new life too. Opening that door to the caravan was to find solace in the imagined roads and stories of past journeys as they retold themselves over and over on the lines of the map that covered the fold-out table. In a world still without television, all we had to divert our attention on rainy holidays were books, board games and maps.

The table map stretched as far north as Zimbabwe and the lower half of Zambia, showing me the location of places with magical names like Kitwe and Kariba and Cahora Bassa. From Mozambique, the map stretched west until it hit the Atlantic Ocean somewhere north of Luanda and Moçâmedes. At the end of 1975, after Angolan independence, Moçâmedes became Namibe, and the thud of land mines and soldiers’ footsteps would ring in the ears of a generation of children as they were maimed into adulthood. But in the caravan in the backyard, I was unaware of such changes. The names on that map were simply places beyond my back garden, places I knew from reciting them over and over again as the storm clouds passed, places I knew I wanted to visit one day. And squashed in the middle between these far-off places and the dot that marked our hometown with the caravan in our backyard, off along the west coast of Africa, lay Namibia.

Even in Canada, Namibia kept inserting itself into my life, reminding me of that year I spent there in 1990, the year of independence. One evening during dinner, I mentioned that I would love to go back.

Between mouthfuls of food, our youngest daughter, Sinead, planned the trip.

“There’s an awful lot of ‘we’ in your plans for me,” I said to the head of red hair that was stretching across the table for more roasted potatoes. “And don’t stretch across the table.”

“By the time you leave, I’ll be done high school. I’m coming with you.” It was more a point of information than a request or a suggestion. She stuffed another roast potato into her mouth.

And so here we were, Sinead and I, waiting to get our passports stamped.

“Well, you’re back now, so you have to apply for one, nè?” The customs official’s voice startles me out of my reverie. “And who’s this?” She looks at Sinead’s passport. “You were not born here, I see. That’s okay. Your dad’s Namibian. You’re one of us. Welcome home.” She stamps our passports and waves us through.

We wait almost forty minutes for our luggage. Sinead gets bored and wanders off to find a bank machine where she can draw some money. Eventually, our luggage arrives and Sinead leads us toward the car rental desk she’d discovered during her forty-minute walkabout.

As we walk out of the building, two men squatting on the ground look up from their game. Owela, a favoured pastime of many Namibians, is one of the oldest forms of mancala and the two men move the stones about with enthralling dexterity. I watch them play as I soak in the dusty green of the camelthorns and the glorious abundance of black skin that surrounds me. The pulsating heat of stone and sand melts into my head alongside long-forgotten memories. I am breathing home after two decades away. The dust of the Khomas Hochland covers my sandals. One of the owela players catches my eye and smiles as he leaps up to offer me a copy of The Namibian. By the time he has pocketed my change, I am forgotten and his mind is already focused on the important matter of winning his game.

We leave the two men to continue their battle of wits and begin the search for the pickup truck we’ve rented. We pack our bags in the back and get in. Before I start the bakkie, I do the unimaginable: I put a map in my daughter’s hands and instruct her to navigate.

Sinead grunts. “You’re kidding me, right?” The map remains unopened in her lap.

Travel, like Africa, is in Sinead’s blood. She grew up between continents on trips back to South Africa to visit family. At eighteen, she knows the best places to snooze in an airport lounge and can navigate her way through customs with her eyes closed. Yet despite her ease with international travel, my directionally challenged daughter cannot find her seat on a plane without the aid of a GPS. Fortunately for her, there is only one road to take from the airport to Windhoek. We enter the city as the sun is setting and head straight for our bed and breakfast. The map of the city unfolds itself from my memory as I round the circle at the Christuskirche, turn onto Independence Avenue and up John Meinert Street.

Sinead had spent the summer before our trip volunteering at a camp in British Columbia where she had picked up a cold. Between the effort of fighting a cold and an eternity in airplanes and transit lounges, she can barely manage to stay awake. We decide to order in. While we wait for our pizza to arrive, Sinead crosses her legs and spreads the map of Namibia out in front of her on the bed. She stares at it for a while before turning to me. “If Namibia has two deserts, where do people find water for farming?”

Namibia’s rivers are not the mighty Yangtze River, nor are they the Nile or some other famous waterway about which numerous books are written. In fact, for much of the year, Namibians complain about the sheer lack of water and the majority of its riverbeds are oversized sandpits. “They use underground water where they can, or they rely on water from the dams they’ve built. The Kunene and the Okavango rivers flow all year round. There’s enough water if people are careful.”

Sinead looks at the map again. “So, that’s desert and that’s desert and that’s dry and that’s wet.” Her fingers drift across the map and settle along the Caprivi Strip in the tropical north. “That’s why most of the people live in the north, I suppose?” I nod, but already she’s off on another tangent. She changes tack sharply, this child of mine. For someone who’s suffering from a cold, jet lag and lack of sleep, she’s pretty chatty. I keep being drawn from my book, Marion Wallace’s A History of Namibia: From the Beginning to 1990, by a barrage of questions. And each time I’ve answered one of her questions, I return to the first chapter, the one that tells the many tales of migration. If there is one thing Namibians do well, it is move. Throughout its turbulent history, the people of Namibia have trekked. People came from the north, from central Africa, to settle around the Kunene and Okavango Rivers. Later, centuries later, some of these people, like the Ovaherero, packed their belongings and headed further south to the central plains, where they came into contact with the various groups of people who had steadily been moving up from the south. These southerners were moerig, a cantankerous lot. Mostly refugees from south of the Gariep River, bandits and escaped slaves who had fled the Cape Colony, they brought with them firearms and a zealous desire to retain their freedom and independence.

I’m trying to make sense of centuries’ worth of convoluted migrations when Sinead pokes me in the ribs for the umpteenth time. “Okay, so we’re going to be looking at graves and things. If the war took place in the north, why are we looking at graves in the south?”

“It’s complicated,” I reply as I go down on my knees and lean over the side of the bed to see the map up close. “It would take a book to explain that.” Sinead rolls her eyes, but I am not really joking. Namibia is complicated. Besides stories of endless treks, there are numerous stories of conflict. This is a country steeped in war. For Namibians, the twentieth century is bookended by two major wars, and packed with enough tales of battle to fill up the spaces in between and spill onto the adjoining shelves. By the time the Germans laid claim to the country in 1884, the local people were already well armed and bellicose. They fought the colonists in the protracted Wars of Resistance that ended only after the first genocide of the twentieth century had wreaked havoc among them. When Germany lost its colonial possessions after the First World War, German South West Africa became a mandated territory under Britain’s care. Britain, in turn, handed over that responsibility to their ex-colony in the region, South Africa. The South African government was to lead Namibia to independence, but they had other intentions. They set about recolonizing the country and incorporating it as a part of South Africa.

By the mid 1960s, Namibians had tired of sending pleas and protests and petitions to the United Nations. In desperation, they turned once more to war. This time, the war took place mostly in the north. For more than two decades, Namibian soldiers moved back and forth across the border, pursued by South African troops who left behind them yet another trail of broken and displaced communities. The Namibian War of Independence lasted until 1989, when a peace accord was signed at Mount Etjo, just north of the capital city, Windhoek. It was a delicate truce that would reveal its fault lines more than once in the lead-up to independence, but it was a truce nonetheless, and that is what mattered most.

“How big is Namibia?” Sinead asks as reception finally calls to let us know that our pizza has arrived. I’ve been asked this question so many times that my answer is rehearsed. “It is more than double the size of Germany, or as big as Alberta and just under half of Saskatchewan put together, or larger than Texas by a quarter.”

Sinead’s questions dry up while she eats. Halfway through dinner, she pulls the blanket over herself and goes to sleep.

After stocking up on groceries at the nearest supermarket early in the morning, we head toward the industrial area to pick up our camping supplies. Sinead turns the map around in an effort to determine which way we’re travelling. She tries to give me directions, but the street names change faster than she can pronounce them. As we stop at the suppliers, she extricates herself from the maps and announces, “We need a GPS.”

“Why? We’ve got maps. Two of them. The dinky one from the car rental people and the proper one we bought.”

“Didn’t you see me trying to read the maps? You know I can’t read maps.”

“Then you’re going to learn how to on this trip, aren’t you?” Sinead stomps ahead. By the time I get to the counter, she’s already ticked off a GPS on the rental form. I leave the details to my daughter. She may not be able to find her shoelaces to tie them, but when it comes to organizing an excursion, I know I’m in good hands. Twelve years of organizing Girl Guide camps means she’s got it nailed. Sinead whips through the form and hands it over to me to sign and pay. I hand over my credit card, but the woman just shakes her head: “Cash only.” Sinead and I return to the city to draw some money. We move from cash machine to cash machine, drawing the daily limit at each bank machine we can find until we have collected what we can legitimately lay our hands on at such short notice. We’re still several thousand Namibian dollars short, but we’ve drawn all we can for the day.

“How are we going to get our things?” Sinead asks. “Where are we going to sleep? We only booked a room for one night. We’ve booked a campsite in the backyard of the hostel for tonight. We need a tent.”

“Have some faith,” I tell her as we head back to tell the owner of the camping store that we will return in the morning when we’re able to draw the balance and collect our equipment.

The owner reaches across the counter for the money as I begin to tell her about our predicament. Her face wrinkles into a laugh and she throws the weight of her head back as she chuckles. “Yes, these machines never give me enough money, either. But that’s because I don’t have any. You can pay the balance when you get back.” She sends us on our way with a flourish that sets the wattles under her arms jiggling. “Enjoy yourselves.” A man with oiled black hair standing behind her turns around and shouts into the back room, “Laai die bakkie!”

Back in the city, we park the car in a lot just off John Meinert Street. It’s almost noon and the throb of approaching midday heat makes me squint. A woman stops us at the corner and says, “Don’t ever walk with a backpack in this city! It’s Windhoek, you know! You’ll be mugged!”

I wish I could turn around to tell her, “You are wrong,” but I know she isn’t. We could be. We could be mugged or robbed in New York or Amsterdam too. Such is the way of cities all around the world. I tighten my grip on the backpack and continue walking when the lights change. We dodge taxis as we cross the road, the softened tar squelching under our feet. Sinead’s eyes dart around, trying to absorb everything.

I could describe how the streets have frayed at the edges, as they inevitably do in almost every African city. I could talk of the cracked plaster and the litter gathering in the street, or the taxis that circle the blocks in search of fares or the intricate array of hand signals that flag them down with explicit instructions on where to go. I could do these things, but that would detract from the new glass and brick monoliths that are steadily elbowing out the old German colonial buildings along the verges of Independence Avenue. Besides, I no longer speak the language of taxis. So much has changed in my absence that I am a familiar stranger in this city.

We stroll up Independence Avenue, past the kudu monument at the intersection with John Meinert Street, toward Restaurant Gathemann. At Gathemann’s, we cross the road. At the Ministry of Home Affairs and Immigration, I run in and collect a passport application. Back outside, swathes of new postmodern corporate high-rises jostle for position among the remaining low buildings of the colonial era. The names of colonial administrators and revolutionaries hang side by side on the street corners in an uneasy truce: Lindequist Street, Sam Nujoma Avenue, Dr. Frans Indongo Street, Robert Mugabe Avenue and Mandume Ndemufayo Avenue all leave traces of the town’s history at the intersections.

We stop briefly at the warrior memorial in Zoo Park. It is unusual for a colonial-era statue to acknowledge the deaths of indigenous peoples, but the Kriegerdenkmal does, which is why it is worth pausing at as you hurry up and down Independence Avenue. An obelisk supports the Kriegerdenkmal with the Reichsadler, the imperial eagle, perched on top of an iron orb. On the side of the monument, we find the names of the five members of the Rehoboth Baster community who died fighting with the Germans against the Witbooi during the Wars of Resistance.

At Fidel Castro Street, we turn and start walking up the hill toward the Christuskirche. The traders on the other side of the road spot us and call us over. The disarrayed ranks of men’s heads jostle for space on the cloth that covers the pavement. Animals migrate to nowhere around them. Phalanxes of carved elephants and baboons and rhinos march into the void of travellers’ suitcases. Among them, the elongated bodies of pitcher-bearing women lie in piles. Yard upon yard of cluttered tourist kitsch that has become the lifeblood of the informal economy. Two Ovahimba women start showing Sinead their wares, bartering and calling out competing prices. Within minutes, they are joined by four more. I watch her struggle to keep track of the wares that have appeared in her hands without her bidding. She looks at me, but I leave her to struggle on her own. She has to learn to barter. They too recognize her discomfort. “She’s never had to barter,” I say to them.

“This is how we shop here,” one of them says. The others laugh and together they coach her through the basics.

“Listen to me, my price is better!” says one of the traders.

“No, buy from me!”

“My goods are better quality,” another woman remarks, pulling up her nose at the handiwork of the bracelets Sinead has in her hands. She stuffs a handful more trinkets into Sinead’s palm. I counter their price.

“I’m happy to pay what she asked originally,” Sinead whispers to me.

“That’s not the point,” I say. “They don’t expect that at the open markets. Just imagine you’re arguing with me.”

Sinead turns to the women and begins to haggle tentatively. They laugh at her and help her along. Eventually they reach an agreement.

“A very good price,” the woman assures her.

While Sinead is haggling, I look around. A short way back from the women, a man is taking care of two children. The little girl has settled herself on a blanket and plays quietly with some of the woodcarvings, but her older brother, who can already walk on his own, darts off and returns with more toys for her. One of the neighbouring hawkers calls to the man and he sends the boy back with her wares. Dad has barely blinked when he makes a dash for his mother.

“I can sell you my child!” the father shouts.

“I already have two,” I reply. “I don’t need another one.” He laughs and runs after his son again.

“He’s healthy,” he says as he catches hold of the boy and returns him to a spot beside his little sister, “no AIDS.”

I know our banter is in jest, but the lines hit home. Namibia has one of the highest infection rates in the world and AIDS is the leading cause of death in the country. I reject his offer more firmly and move on.

We cross back over Fidel Castro Street and head to the Christuskirche at the top of the hill. While Fidel Castro needs no introduction, my eye catches the name on the side street as we dodge the traffic. It is named in honour of Reverend Michael Scott. It was he who presented a petition to the United Nations on behalf of Namibia’s people, asking the international community to force South Africa to commit to the obligations of their mandate. A simple action, perhaps, but one that planted the seeds of revolution that would flower into independence. After the cold numbered streets and avenues of North America, it is fun to play a gentle game of Know Your Revolutionaries as you walk past Robert Mugabe Avenue or Fidel Castro Street. At the traffic circle, we cross the road onto the island on which the Christuskirche stands.

Rock agamas peek at us from their perches along the sandstone walls of the church. Their yellow and black heads dart this way and that, this way and that as they scout out intruders into their reptilian world. The white accents on the windows shimmer in the sunlight and it is a relief to enter the coolness of the church. Inside, just past the marble portal, a man reclines as best he can in his straight-backed chair. His entire outfit is khaki – from the shorts and socks to the billowing safari shirt. He says little, but the imperial wave of his hand indicates that he may be a guide. After fielding the first questions from the group of German tourists ahead of us, he moves his chair into the back corner. From this new position, he returns to riding the chair, pushing himself onto tiptoe to tilt back with the rhythmical precision of one who has practised this move over many years. Each time his ankles rise, the buttons on his shirt strain in protest. Back and forth he rocks, back and forth, breathing heavily as he tosses fragments of German at no one in particular. At the conclusion of each utterance, there is a muffled whiplash as his rocking-horse chair hits the back wall of the church. Back and forth, back and forth the Reiter rocks as we admire the stained glass windows and the clean lines of the Italian marble altar in the art nouveau interior of the building.

The Christuskirche was built in 1910 to honour the peace that ensued after the Wars of Resistance. Along the wall of the church eight panels list the names of the Germans and Europeans who died in the war. The bleak silence of war beats body and mind into re-recognition of the horrors we bring on ourselves. We look for names we might recognize – a friend, a family member, a fabled hero. Yet as I stand before the Schutztruppe Denkplatz, the plaque against the wall throws back only the silenced whispers that once belonged to the Nama or Ovaherero who died in the futile bloodshed.

Back outside, we walk around the church and then cross over to the Tintenpalast, the Ink Palace. The gardens stretch up endlessly and here and there, I spot statues of heroes of the Struggle. We try to get in, but the main entrance gates are closed and neither of us feels much like walking around or climbing fences. It’s a lazy do-as-tourists-do afternoon and we take more photos before heading down Robert Mugabe Avenue on our way back to the bakkie.

For the most part, Windhoek is a pretty but nondescript city. A few buildings, like the Gathemann House, stand out. The Alte Feste is a fort: its austere white walls have changed little over the past century-and-a-bit since it was built. A few blocks north, the imposing sandstone of the Tintenpalast lies far back in the expansive Parliament Gardens. The Old State House lies halfway down the hill from the Parliament Gardens, hidden behind a wall that only the privileged get to see behind. When this building was deemed insufficient for affairs of state, the government commissioned a new State House, a North Korean design of extraordinary brutality.

Right beside the Old State House lies Daniel Munavama Street, a short side road that is barely a hop and a skip from one end to the other. An air of disquiet envelops me. I recognize the landmark buildings that surround it, the hues of light and the ramp that leads to the car park behind Zoo Park. Slowly the change dawns on me. “This used to be called Göring Strasse,” I tell Sinead. One does not forget a name like that. For many visitors to pre-Independence Windhoek, encountering this street name remains the lasting memory of the city. “It was named after Heinrich Göring, the first Imperial Commissioner of German South West Africa. And yes,” I add, “he was Hermann Göring’s father.”

We cross over John Meinert Street and walk in a loop down Bahnhof Street, past the Turnhalle building and the old station building. It was here, in this old gymnasium in the Turnhalle, between 1975 and 1977, that the first attempt was made to create a Namibian constitution. Despite the fact that the United Nations did not recognize South African rule in Namibia, the South Africans attempted to create a constitution that would give Namibia self-rule while remaining under South African control. Understandably, the South West Africa People’s Organization (SWAPO) refused to participate and the conference failed. On the corner, the imposing facade of the Bahnhof impresses visitors, as it was meant to do. Outside the building, Poor Old Joe, the narrow gauge train that was reassembled in Swakopmund for the run to Windhoek, has place of pride.

At the backpackers’ lodge where we’re staying, I find the receptionist outside planting bulbs by the front gate. “Sword lilies,” she announces proudly. “You need sturdy things to survive in this climate.” In the bar, they’re playing a song by Zimbabwe Dread. A group of twentysomethings wander in and out with their plates of food. They all have a look of well-travelled dirt about them that suggests the carefree attitude that comes with plenty of free time. They chat effortlessly, and I eavesdrop on their conversation while I have my beer. The majority of this group have been drifting from lodge to lodge on their way south from Cairo; the twenty-first century grand tour. Places are rated by their party value. Windhoek scores low on their scale. There is little awareness of the weight of the history that surrounds them.

We sleep cold that first night in our tent: in the early days of spring, the night air is colder than I remembered or expected and the canvas walls of the tent offer scant protection. In the morning, we gather in the breakfast lineup at the bar: a cup of coffee and crepes doused in cinnamon sugar and butter. Our plan is to spend a few days in Okahandja and surroundings so that we can attend the annual Herero Day festivities. Before heading out to buy warmer sleeping bags, we stop by reception.

“Yes,” the receptionist confirms, “it says in our handbook ‘The festival is held on the third Sunday closest to August 23.’ That’s this coming Sunday.”

With that information in hand, we set out for the day. Our first stop is the camping store to find warmer sleeping bags. From the camping store, we make our way to the Alte Feste, the oldest surviving building in town. As soon as the Germans arrived on the eighteenth of October 1890, they laid the foundations for a fort to protect their troops. Windhoek changed hands regularly during territorial disputes, and each time it changed hands, it also changed names. Jonker Afrikaner, Captain of the Oorlam, settled here in 1840 and named the place Windhoek. The Ovaherero settled there for a while, calling it Otjomuise, Place of Steam, after the hot springs that bubble out of the mountains. Likewise, when the Nama occupied it, they referred to it as |Ai||gams, Fire Water. Through all these wars, the buildings of the once prosperous town disintegrated and by 1885, little more than a handful of neglected fruit trees and its original name, Windhoek, remained. When the Germans arrived, they changed the spelling rather than the name of the town: Windhoek became Windhuk. Later, when the South Africans took over the administration of the territory in 1920, the name changed once more – back to Windhoek, which has remained its name ever since.

General Curt von François had his Schutztruppe build the fort on the top of a hill, from where they could command a good view of their surroundings. And indeed, the view is breathtaking. Windhoek and the Auas Valley stretch endlessly before us, but a niggling thought from the previous day has resurfaced and I cannot appreciate the view. Slowly, it dawns on me: Where Parisian flâneurs provide direction simply by conjuring up the name of a rue, Namibians use their monuments as points of reference. There are statues at the one end of Independence Avenue and statues at the other end. And in between there are monuments and statues in Zoo Park and other places. Namibia has more statues and monuments per capita than any other place in the world. There are South African colonial statues, German colonial statues and memorials and, since independence, an increasing number of new statues to honour the heroes of the Struggle. “At the kudu statue, turn left,” the people of Windhoek say. “Head along Independence Avenue until you see Curt von François in front of the town hall . . .” And so on. Heaven forbid that a landmark should move. What chaos could ensue! And there you have it: The Reiterdenkmal, the statue that commemorates the courage and valour of the German Colonial equestrian soldiers, no longer stands at the top of the hill commanding the gaze of motorists as they round the circle. That is where it still belongs in my memory; now it guards the entrance to the Alte Feste museum. Where it once stood, an imposing concrete structure, still veiled in plastic drop cloth and scaffolding, is taking shape. The relocated Reiter stares resolutely, daring intruders to move him again.

We pass by the shadow the Reiter casts and ascend the steps that lead to the museum. The front porch houses an array of old machinery: a fire engine and a tractor, a wagon or two and a cannon. In the corner, off to the right as you approach the door, stands a huge woven Oshiwambo grain basket. We examine these artifacts before entering the extraordinary, delicate creature that is the museum. Over time, museums develop lives of their own, become tiny microcosms that reflect and often oppose the world outside. The Alte Feste houses the State Museum and Sinead and I spend a few hours wandering through the exhibits. If the imposing colonial statues outside lull your mind into some false cultural amnesia, you come here to forget that legacy and focus instead on the path to liberation and independence. I linger at the independence exhibit, remembering old friends in photographs and becoming reacquainted with the sounds and smells of that year.

Back in the courtyard, Sinead turns to me. “This place reminds me of Robben Island. Both were designed as prison yards and both housed political prisoners.”

Outside the Alte Feste, we take in the view of the city stretching along the valley. I put my arm around Sinead. “Take a good look at what you see around you,” I tell her. “Now close your eyes. Imagine guards in the turrets of the Alte Feste looking out over the five thousand prisoners in the largest concentration camp of the Wars of Resistance.”

Namibians talk about roads the way Canadians talk about the weather. Everyone we ask, including our rented GPS, tells us that the best way to get to the Spitzkoppe is to head north to Okahandja and then take the tarred road to the coast. Naturally, we therefore choose the scenic route through the Khomas Hochland. We are barely out of town when the tar is replaced by a stony road that is badly in need of scraping. Namibian roads are generally in very good shape, but in that interim between the first rains and the arrival of the graders, potholes flourish. Some partridges scuttle across the road toward the water that has dammed in a one of the potholes. As we approach, they rush off into the grass, yellowed from the winter, but already tinged with the green of spring.

About eighty kilometres from Windhoek, we stumble across the dilapidated stone ruins of the Von François Feste, the fort General Curt von François built as a halfway post when he moved his headquarters from Tsaobis to Windhoek in 1890. The sign at the entrance gate on the way up to the fort is pocked with several new bullet holes. Drive-by target practice is the sport of young farmers everywhere, but in Namibia, the neat 9mm holes are a reminder that despite the peacefulness of the surroundings, this has always been a country filled with weapons and warfare.

The footpath up to the fort is lined with pyrite – fool’s gold. When I came to Windhoek to teach in 1990, the streets of the city seemed to be paved with gold too. There was a shimmer of optimism in the streets of Windhoek, and a real desire to leave the past behind. This was a nation weary of war and as Independence Day approached, we celebrated each step toward the withdrawal of the United Nations Transition Assistance Group (UNTAG) and South African Defence Force (SADF) troops from our country. On my early morning walk to work every day, I would marvel at the specks of gold that flecked the pavement ahead of the rising sun. Optimism, when so many doomsayers were predicting the end days.

Here at the Von François Feste, the pyrite reflects the folly of the early settlers who came to find the fabled mineral riches of this desert El Dorado. Most left clutching little more than their memories. It is the silence of this place that overwhelms you. The immense, almost oppressive silence of the Von François Feste and the Khomas Hochland. Like elsewhere in this country, there are things these stones and this veld remain silent about. Stories that remain untold. The tightly packed stones wait for the alert eavesdropper to uncover their story. Their’s is a story of an arduous journey from Tsaobis, the hurried movement of cattle and troops and horses being rushed through the treacherous Bosua Pass and up the Khomas Hochland. The original fort was built in haste during the flight from Tsaobis to Windhoek. After the troops had settled in Windhoek permanently, it became a cattle outpost and a trockenposten – a place where alcoholic soldiers were sent to dry out.

There could be worse punishments. The view over the Khomas Hochland is endless and even after winter the stream in the valley runs strong. The strategic value of the post is evident from the view, the easy access to water and the lushness of the grass. The stones are packed tightly in their serried rows, each one carefully hewn and placed. As I bend in close to admire the seamless stonework, a large cattle truck roars past. Each of the densely packed two-foot-wide walls is squared beautifully, held together without any mortar. Only water and lizards wriggle through this rock now. The warmth of the stone comforts me. Swallows circle in thermal currents above us. A hawk hovers briefly over the fort like an aerial sentinel, then catches a ride across the valley on the whorls of air that surround us. It returns at intervals to observe our movements. Here, as in the city, the remnants of the Kaiser’s Reich are everywhere: in the farm names, in the buildings, in the monuments. Tiny snippets of information scattered across the stones. It takes patience to draw stories out of such silence.

After a while, the silence of the fort becomes overwhelming. The rattle of a convoy of bakkies intrudes briefly, but in the end, the silence wins out. You become aware of the blood pulsing through your veins and gradually you are filled with the first racking sensation of loneliness that comes from being in open spaces. This is inhospitable, dry territory and life among the rolling hills is deceptive and tough.

We catch up with the bakkies a short way down the road: they’re all parked at the upper end of a huge parking lot. Off to one side, a lone cattle truck. As we drive past, we see men mingle and twist around the open spaces, lizards trying to pry a way through the rock walls. Two men in the watchtower by the cattle pens give the proceedings a purpose: today is vendusiedag. Auction day. The first spring auction in the Khomas Hochland is a celebration. Farmers from all around gather early in the morning, vying for the prime spot at the auction lot. The cattle milling in the pens glisten with fat. Soon, the auctioneer will begin the bidding war and farmers will trade their cattle, measuring the success of the season by the condition of their beasts and the size of their cheques. In the background, I see the fires starting up – after the auction, they will gather and feast.

I would love to stop, but I want to get to the Spitzkoppe before dark. Too soon, the familiar childhood smell of cattle and dust fades. As the Von François Feste recedes into the background, I open up to the spectacular views of the countryside. A small herd of kudu ewes peeks at us through the bushes. A flock of African hornbills clusters at the side of the road like inquisitive beggars. Yet the sheer drops and the loose sand in the Boschau Pass make driving treacherous. It is easy to forget that this fertile stretch has for centuries been a battleground and that, even today, the land remains contested. Above us, the vultures circle, endlessly rising on the air currents and disappearing from sight, only to reappear low above the valley and circle us again.

The pass folds between mountain ranges and it is hard to know where one range ends and another begins. Once we’re through the pass, the hills begin to flatten and soon we reach the turnoff to Karibib. Gone are the folds and precipitous drops of the Khomas Mountains. In their stead, the valley opens before us and the closer we get to Karibib, the more the copses of camelthorn trees thin out and make way for grasslands. We are approaching the desert. In the distance, we can see the rusty outcrops of the Witwatersberge and the copper glow of the Otjipatera Mountains. Somewhere in those hills lies Tsaobis, where Captain Curt von François established his first fort. Von François was belligerent by nature, and felt that the native population had to be treated with a firm hand. To make his point, he established the fort at Tsaobis directly on the trade route between Walvis Bay and Otjimbingwe, where many Ovatjimba – Ovaherero who had no cattle – had settled at the Rhenish mission station. It was a poor choice, bred out of inexperience and a lack of familiarity with the land. Squeezed between Otjimbingwe and Kaptein Hendrik Witbooi’s people, the small contingent at Tsaobis was constantly under threat. In 1890, Witbooi demanded permission to water his cattle at Tsaobis. When von François refused, Witbooi attacked. The woefully outnumbered German Schutztruppe retreated to Windhoek in a great hurry, erecting the Von François Feste as a temporary shelter along the way.

The closer we get to Karibib, where we will leave our scenic route through the Khomas Hochland and join the main road to the coast, the more prominent the veins of calcite along the mountain ridges become. In Usakos, I realize I’ve driven through towns like this countless times before: a stretch of tar that runs from the edge of town to the edge of town. A bank, a grocer, a church and a recently painted town hall. Everything looks clean because there is bugger all else to do but sweep the streets. Even from the moving car, the marks left by the straw broom on the compacted sand of the pavement are visible. Only the garage at the entrance into town shows signs of life. Beside the garage, a lone man leans on the crowbar he uses to dislodge punctured tires from their rims.

We drive past the garage and round the corner to where the road out of town should be. Somehow, we find ourselves in a maze of streets, so we stop to ask for directions at the local café. Sinead decides to wait in the car while I run in to ask for directions. A bulwark of glass counters separates the merchandise from the customers. Glass jars brimming with sweets line the top of the counters, and behind them sits a woman of indeterminate age. Her carefully curled hair has begun to sag as the day wears on, yet when a group of tweens on their way home from school shove their way past me and into the small space between the door and the counter, she extends herself with the wariness of a cobra preparing to strike. They push and shove their way to the counter, demanding her attention.

I see the woman’s eyes flit from one youth to the next as she watches their movements. Her hand descends with unerring accuracy onto the fingers that reach for some sweets on the counter. “Don’t touch! I’ll give it to you. Show me the money first!” In their rush to get past me, the cluster of youths have pushed aside an old lady and her assistant who entered before me. They are still setting down their bags and untying the blankets the younger woman uses as an abbavel for her child. The youths crane their necks and wiggle like meerkats fighting over grubs. The woman behind the counter takes their money and shoos them out. As the youths head out of the café, the old lady draws back behind the glass door. The woman behind the counter turns her attention to me. I hold back and wave the old lady through. She smiles and rattles off in Damara. Her assistant, the younger one, turns to me with an equally big smile. “Dankie,” she says. “Die kinders vandag respekteer nie meer hulle ouers nie. Die Bybel sê mos jy moet jou vader en moeder eer.” Thank you. Today’s children don’t respect their elders. The Bible tells us to respect our fathers and mothers.

As the woman shuffles back into the street with her package of goods, I ask the woman behind the counter for directions to the Spitzkoppe.

“Ag no,” she says, “I’m not the best person to ask. I have seldom left Usakos in my lifetime. Ask Banie at the hardware store next door.”

Outside, two men enjoy their coffee and a cigarette on the small porch. One of them must be Banie, I decide and walk over. “The tannie next door at the café said I should ask Banie at the hardware store for directions,” I say to the man seated at the door. His head barely moves as his eyes scan my body. His disdain for out-of-towners is apparent, but at least I can speak Afrikaans. With an almost imperceptible gesture, he tilts his glowing cigarette toward the road.