11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

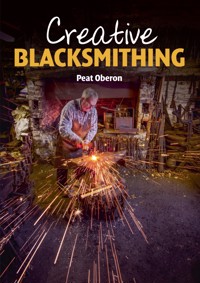

Discover the thrill of working with hot metal and creating your own pieces. This book shows you how: with lavish photographs, it captures the excitement of working at the fire and explains the techniques to get you started. Drawing on traditional methods, it encourages you to develop your own style and to design your own tools and creations. Step-by-step instructions to shaping, bending, splitting and drawing down hot metal are given along with advice on traditional methods to fasten metal pieces together. Projects included in this new book are making a hanging basket bracket and a toasting fork. Aimed at blacksmiths, sculptors, metal workers and farriers, Creative Blacksmithing explains the techniques required to get started, how to make your own tools and tongs and how to help create your own designs, in particular leaves and organic forms. Superbly illustrated with 176 colour photographs.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 148

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2015 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2015

© Peat Oberon 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 034 8

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

1 GETTING STARTED

2 BASIC TECHNIQUES

3 FASTENINGS

4 MAKING YOUR OWN TOOLS

5 PAIR OF TONGS

6 LEAVES AND ORGANIC FORMS

7 HANGING BASKET BRACKET

8 RAM’S HEAD TO ASTING FORK

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

INDEX

INTRODUCTION

Blacksmithing is of one of the oldest crafts. People who want to develop these blacksmithing skills may come to it from a wide variety of other activities. You may already have the kit and want to do something less functional that allows you to express yourself creatively. You may be skilled in other creative crafts and want to expand your materials and skills repertoire to include blacksmithing. You may even have a project in mind and are intrigued by how forging is done. Rather than buying a ready-made product, or commissioning someone to make it for you, you may well become so fascinated that you want to do it yourself.

Unfortunately for would-be practitioners, blacksmithing is rather equipment-hungry. You will need something heavy and flat, preferably an anvil, upon which to hit the metal, and a hammer to hit it with. That is the way most smiths start out on their journey of exploration.

We will begin by learning about the anvil and using fire, especially managing the various techniques needed to control and manipulate the heat. Please note that the availability of fuel varies from place to place; this book refers to the use of coke, which is universally used in Britain, but coal and charcoal require different tech-niques.

In the course of time, as your knowledge, experience and skill accumulates, the need will arise for more and more tools. A selection of hammers for various tasks should be available for the smith’s use. There are five types of tongs described in this book, and later, a chapter showing how to make your own tongs.

Almost uniquely in the world of making, smiths have the ability to make their own tools. Besides hammer and tongs, to perform any tasks except pure forge work, other tools must be available. These will be collected or made as progress demands. Hitherto, it has been assumed that the novice has had access to tools from ‘elsewhere’. However, if there is more than a passing interest, the blacksmith will need some personal tools, which do not need borrowing. During working, having the right tool handy to help the flow of the job will enhance a sense of achievement, and reduce frustration. Besides which, there is a lot of satisfaction to be had from working with your own homemade tools.

Basic techniques, such as drawing down, bending, marking out and splitting, will be explained, and you will be able to practise these and more advanced processes while working on various projects involving the introduction of skills of growing difficulty. In the first few chapters all of the instruction is about traditional ironwork, and the tools with which it is made. These are the building blocks, necessary to lay down before you can express your creativity.

In Britain, until recently there was a very stuffy attitude towards ironwork. Architectural styles changed, but to a large extent, ironwork lagged behind. Smiths themselves were not encouraged to experiment, and the paragon work of Jean Tijou (active circa 1690–1710) continued to be held in high esteem. There were exceptions, obviously, and some really innovative work was done in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. After the Art Deco period, however, ironwork declined, and was dropped from architectural studies. Some of the good work from those periods was quite organic, and in Chapter 6 we will demonstrate some of the techniques employed in its manufacture.

Whatever experience you bring to this book, and whatever you hope to achieve, it has been written for present-day craft explorers to enable everybody to unfold some of the mysteries of this fascinating, ancient craft.

CHAPTER ONE

GETTING STARTED

The anvil

The smith’s most important piece of equipment is his anvil. In Britain, the most usual kind of anvil is the London Pattern. This shape evolved about 300 years ago, and has hardly been bettered. There are also Birmingham Pattern and Portsmouth Pattern anvils in use, as well as various other slightly different models.

London Pattern anvil; the most popular shape used in Britain for 300 years. The height of the anvil should enable the smith to rest his hand upon the anvil while keeping the back straight.

Birmingham Pattern anvil; similar to London, but missing the table.

Portsmouth Pattern; similar to Birmingham, but with extra squared-off beak at other end.

Parts of the anvil

The beak, also called the bick, beck, pike, horn and other names, is the prominent characteristic of the anvil. Because of its tapering shape, it has an infinite number of radii, used in creating curves.

The square hole at the other end, the heel, of the anvil is called the hardie hole. It is so named after the cutting tool, which is the most frequently used anvil accessory. During a lifetime of working, a smith will invent – and copy – innumerable square-shanked tools to be secured in that hole.

Heel end of London anvil, showing hardie hole and pritchel hole.

Selection of tools for hardie and pritchel holes, where they can be seen.

Beside the hardie hole, there is another, smaller, round hole called the punch hole, or pritchel hole. This is used to support flat material when punching through the metal; because of its malleability, the material around the hole would otherwise be forced down around the hole and need re-flattening.

The face of the anvil is hardened. Even though the metal is hot and soft when it is being hit, the face needs to be hard wearing. Until the nineteenth century, anvils were made of wrought iron, and the face, of hard steel, was fire-welded on. After time in use, the body of the anvil would slightly compress at the left, most-used part of the face, and it would hollow. Forged (wrought iron) anvils have holes under the beak and heel where the huge tongs were deployed in placing the anvil in and out of the fire during manufacture. Present day anvils are usually cast steel, and have no holes. They do not hollow so much.

The beak is usually placed at the left when the anvil is used by a right-handed person. At the opposite side of the face, at the left hand end, is a small radius. This is used for a variety of reasons, which will be explained as we progress.

Radius at left end of face.

Height of the anvil

For ergonomic reasons, it is fairly important to adjust the height of your anvil to your needs. You can end up with a sore back if it is too high or low. To assess the height, stand beside the anvil, with your arm hanging down beside you and place the palm of the hand straight out, it should rest gently on the face of the anvil. If your arm is bent, the anvil is too high, and if you have to bend your body, it is too low.

Stand

Many anvils are supplied with a cast iron stand. These are usually too low, because they are meant to be used in an industrial situation, where a striker hits the tools upon the metal with a sledge-hammer. They also seem to increase the noise emitted by the anvil. In the traditional country smithy, the anvil was placed upon an elm trunk, which was sunk about two feet into the earth floor.

In a modern shop, where space is usually at a premium, a steel stand, which is movable, is convenient. Brackets for accessories and tools can be welded on to one of these stands, too.

Steel welded anvil stand, with retractable container for quenching pot in front of smith, and scroll iron in socket.

Other side of steel welded anvil stand, showing brackets for frequently-used tools.

FORGING SCALE

When you are forging, the hot metal oxidizes, shedding ‘scale’ (Fe3O4) on the anvil face. This scale is very hard, and can cause marks on the underside of the metal you are working. It is advisable to blow it off, or swipe it away, as you work.

The fire

Side blast and bottom blast

There are different kinds of fire – sometimes called a forge (but a forge can also refer to the building). The fire usually associated with rural and industrial use is the side blast, but the modern fire usually used abroad, and for the artist blacksmith, is the bottom blast.

The side blast has a tuyere (tue iron) through which the air is fed into the fire. It is made of either cast iron or mild steel, and has a double skin with water circulating inside. The water is fed from a bosh (tank) situated at the back of the fire and circulates by convection, to prevent the tue from overheating, which could cause it to burn. The danger in this is to forget to top up the water, and the tue burns out. This is a very expensive omission. Obviously the water evaporates, more so when hot, so that it is essential to check the water level every morning before lighting, and more so when using the fire at a high temperature.

Water bosh at back of fire, with air regulating valve.

The bottom blast is fed with air through a tue in the base of the fire.

The side blast fire is usually on a table with the supply fan underneath. There are quiet fans, which run all day unobtrusively, although some of the older types of fan make a terrible noise.

The base of the fire is forge dust, one of the inert products of combustion. The fuel sits on the dust, and is raked into the fire as needed.

The air supply needs to be variable. There are different kinds of valves for this job. Some fans have a motor whose speed can be regulated by a rheostat. If it is a noisy motor, this is essential, but it does not matter much with a quiet fan. The fire must be able to change for different conditions.

Lighting the fire

Old coke is raked away from the tue, exposing some clinker from the previous working. Clinker is the silicon from the fuel, turned into a crude form of glass, which drips down through the fire and forms a lump. Having a very high coefficient of expansion, it hardens as it cools and cracks with a ‘clink’ and hence the name.

Throw the clinker away, and make a dish-shaped depression in the dust, about 100 deep and 150 across, in front of the tue (side blast) or above the tue (bottom blast). There is always plenty of dust created during working, so some must be discarded each time you light. (Note: throughout the book, unless otherwise stated, measurements are given in mm, but in blacksmithing the unit is customarily omitted.)

Kindling sticks, about 125 long, will be needed, and some old newspaper. Roll up three or four sheets of paper into a ball, and place in the hole. Spread about fifteen sticks around the paper like a wigwam, and switch on the blower. The valve should be almost closed. Light the paper, and introduce a breath of air, sufficient to blow the flame on the paper. Keep an eye on the sticks, and when they start to flame, rake some (preferably old) coke onto the sticks. Always leave a hole in the top of the pile of sticks, to let the smoke out, and it will shortly ignite as a flame. Build the coke around the sticks and it will slowly ignite, and the whole thing will be ready to use in about five minutes.

Fire cleaned out, ready for lighting, showing side blast tuyere, ball of paper and kindling sticks.

Conserving fuel

Fuel is expensive, so keep the blast down most of the time. Metal will heat in its own good time, and regulation is slowly learned. Students and other learners have huge fires, wasting fuel. The experienced smith will work with about a quarter of the size of fire. One of the perils of big fires is that the temperature inside is beyond the burning point of steel, and irretrievable damage is easily done. Students’ scrap bins are full of burnt metal.

Watch the colour

It is best to keep withdrawing the metal from the fire constantly, to check the colour of the work. The progression of colours goes from black heat to maroon, to blood red, to bright red, to orange, to yellow, then white. Orange is the best colour to work with. Malleability changes radically through the colour range, and if you are trying to change the shape a lot, it needs to be orange.

The effectiveness of the hammer is dulled as the temperature drops. This is sometimes useful, because when, for instance, you are trying to impart a smooth finish to the work, blemishes can be removed with light blows at maroon heat.

Fire management

Fire management, or forge management, has many facets, and some people never get the hang of it. Observation is of prime importance. There are dangers, which should be known, and avoided. Apart from keeping yourself out of the fire, and avoiding picking up hot metal (which is easily done), you need to respect the dangers inherent in the coke.

Coke explosion

During coke manufacture, coal is heated in a sealed oven, to drive off volatiles such as gas, benzene, tar, pitch and others. What is left is almost pure carbon, which is ejected from the coke oven and quenched. The resulting smokeless fuel is used by smiths as a convenient way of heating metal.

During the quenching, small amounts of water can be absorbed into orifices in the coke. If this is driven off slowly, at the side of the fire, that is fine; if, however, the coke is put directly on the fire, the water in these holes is heated fiercely and can explode with a loud bang, which is often accompanied by very hot pieces of coke flying at the smith. (Water expands 1,700 times when turning to steam.)

Carbon monoxide

When you look at a smithy fire you can see small, semi-luminous flames which have a bluish tinge. This is carbon monoxide (CO) – a deadly poison – burning off, to form carbon dioxide (CO2), which, though not poisonous, does not support life. If you extinguish these bluish flames by putting wet coke on the top it allows the CO to escape into the atmosphere. This is dangerous. The coke should, therefore, be introduced at the edge of the fire, and drawn closer to the centre gradually, leaving the flames to burn off, to CO2.

Leaving the fire safely

If you need to leave the fire during the day, get a piece of wood, about 150×100×50. Rake a large hole in the coke, and place the wood in it. Cover the wood with hot coke until it is completely submerged, and switch off the blower, and the wood will turn slowly to charcoal. You will be able to leave it for about an hour and a half. When you return, restart the fan, and the fire will spring into action very quickly – a minute or so.

FIRE TOOLS

Apart from the rake, it is good to have a poker and a shovel (sometimes called a slice).

A good tip – especially when you are busy – is to have different handles on them, so you can glance down and pick the right one without having to look at the other end.

Fire tools, showing different ends, so the correct one can be seen at a glance, saving time when busy. Note how shiny they are, from frequent use.

Equipment and tools

The rake

The rake should be the most-shiny piece of equipment in the forge. It sits on the fire, and is used each time the work is put into the fire.

The fire should be a shallow upturned cone shape, and should not be allowed to develop into a hollow. That is because the shallower the fire, the nearer to the clinker the work gets. Clinker adheres wonderfully to the metal, and although it is semi-liquid, it has a high density. This causes deep marks to be made on the surface if clinker remains during forging. Raking the surface of the metal after withdrawal from the fire should clean it off.

The rake should be held so that the blade is horizontal. The dust around the bowl of the fire will eventually consolidate, except for the immediate surface of the bowl. The fresh coke will lie on the dust and be drawn easily into the fire. If you turn the rake so that it is vertical, it will disturb the dust and draw it into the fire. Of course, the dust is inert and will impair the working of the fire.

Bench

It is advisable to have a bench, with vice attached. Because of the boisterous nature of working in the vice, the bench should be very sturdy: 50 or more thick for the top, and 75 square at least for the legs. The bench does not need to be very big; 1200×600 is enough, but the bigger the better. However, the more surface, the more clutter you can expect to collect upon it.

Vices

Leg vice