20,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

Drawing is at the heart of all art and this inspiring book gives new ideas and techniques to help artists, whatever their ability, realize their visions. Based on years of teaching and artistic experience, Creative Drawing Techniques explains how to get the best out of different materials and express ideas, gain confidence and develop skills on paper. It emphasizes the importance of looking, analyzing and interpreting what we see. In doing so, it provides a rich and inspiring account of a basic but sophisticated need to make sense of the world around us. This book will be valued by everyone who wants to pick up a pencil and enjoy the creative art of drawing.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 365

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Potteries Memory: Alleyway, acrylic on A1 paper.

First published in 2021 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, Marlborough Wiltshire SN8 2HR

This e-book first published in 2021

© David Brammeld 2021

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 913 6

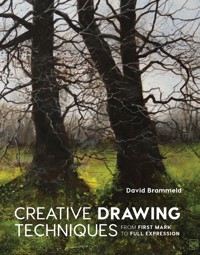

Cover design: Peggy & Co. Design Front and back cover wraparound image:Spring Green (Delamere Forest), acrylic on board, 28 × 39cm

Image credits:All photographs and illustrations by the artist except the two top photographs on p.85, showing the artist painting in Trentham Gardens, by kind permission of Annette Hewetson.

Disclaimer: The views and techniques expressed in this book are the artist’s own, and have been formed by many years of experience and experimentation, and are entirely subjective. There are many alternative ways and different media that can be used to achieve similar results. The intention is to encourage the reader to explore, experiment, enjoy and find their own personal artistic vision.

Contents

Introduction

1Getting Started

2The Language of Drawing

3Developing Your Style and Ideas Through Sketching

4Choosing a Subject

5Drawing from Life or from Photographs

6Developing a Drawing

7Exploring the Potential of Dry Drawing Media

8Working with Wet Drawing Media

9Projects and Practice

10Presenting your Work

Conclusion

Selected Bibliography

Recommended Materials and Suppliers

Index

INTRODUCTION

Drawing is the most enjoyable thing. That is a bold opening statement, but the joy of being in front of a subject that you have chosen to draw – and then of trying to figure out how to get it down on paper with a pen or pencil so that you capture something of its essence – is simultaneously frustrating, challenging, but also immensely rewarding and worthwhile.

Autumn Wood (detail), pastel on A1 paper.

This book’s intention is to be a celebration of drawing in all its forms, and to challenge perceptions of what drawing is and what it can be. It will encourage you to experiment with new techniques to build on your existing skills, enabling you to follow a more creative path in your art. It will explain and explore creative ideas that will inspire you to try new things. Above all, it will help you find an expressive response to the chosen subject.

It is also the intention of this book to impart good practice and to give sound, practical advice informed by my many years of experimentation and development as a professional artist.

Good drawing will always be admired and revered because it is very difficult to do well. People gaze in wonder and admiration when an artist captures a likeness of a sitter with just a few well-chosen marks. Fellow artists admire different qualities of mark-making in the drawings of their peers; they acknowledge and respect good drawing. Drawings by the Old Masters will always be a source of reference, inspiration and wonder that have stood the test of time, proving that examples of good drawing have been around for a long time.

A great subject to draw in its own right: the physical evidence of many hours drawing. I have a jar that I keep these worn-out pencils in. There is still more mark-making to be had from these stubs – they can be used with a pencil holder – and sometimes they are easier to draw with in certain conditions than a new pencil.

As our own drawing progresses, we develop a personal, recognizable style of mark-making that is unique to ourselves. In the same way that we have an individual handwriting style, so do we have a recognizable drawing style: our individual way of making marks.

You will find within these pages guidance on sound drawing principles and advice on the choices of materials available, so you can make informed choices as your experience grows and you seek new challenges. You will find different approaches and styles, as well as encouragement to experiment wherever possible and be more creative. The idea is to help you develop your own style through practice and experimentation.

The book is meant to be a creative resource, something you can pick up again and again as your skills develop. It will challenge you to try new things. Indeed, you will discover that it is through exploration, making mistakes and learning how to rectify these mistakes that you can make progress. A good artist always pushes forward, seeking a new challenge, and is willing to take chances.

The importance of drawing

A few years ago many people were mourning that drawing was dead. As art schools removed traditional, mandatory activities like life drawing from the curriculum, a whole generation of art students began their careers without actually having been taught sound drawing skills. The focus at the time was on ‘the concept’ rather than traditional drawing and painting. The ‘idea’ was more important than ‘practical’ skills. Drawing from the life model was traditionally considered to be one of the best activities to develop drawing skills: proportion, form, line and tone would all be tested during the sessions. The ability to accurately represent the human figure is one of the most challenging subjects for an artist.

With this treescape I wanted to capture the busy energy of the tree. Absolute accuracy was not the objective. A picture can have many intentions: to convey emotion, movement, calmness and so on. Here I have used a selection of pencils and graphite sticks in a direct way to create texture and movement.

Thankfully that situation is no longer the case, with successful representational art societies leading the charge. The popularity of the Mall Galleries, which hosts nine top art societies, is considered the epicentre of figurative art, showcasing work by the best of this country’s practitioners of representational as well as abstract art in a variety of different media, from oils, acrylics, watercolours, pastels and printmaking to sculpture and so on. In fact all wet and dry media, and in every combination. There are abundant drawing groups and organizations like urban sketchers, which are continually expanding their memberships and activities. There are many life drawing groups for all abilities. These days, many people enjoy sketching, and the popularity of social media platforms means that results can be shared in an instant.

Drawing is essential to so many creative areas – most obviously as a precursor to painting, but designers and architects rely on drawing skills to convey ideas and concepts (although much of this work is computer generated nowadays). Whether it’s using a pencil, charcoal or a paintbrush, drawing can be used as a means of getting ideas down on paper to test if they will work. It can be used as a form of visual note-taking or as an art form in its own right. The addition of a little sketch adds so much more to a holiday diary, even if it’s just a little scribble.

Good drawing underpins good painting: no matter how loose or impressionistic the style of painting – the marks still need to be in the right place – the drawing is the foundation.

Perhaps because drawing is undervalued by the art-buying public, the status of a painting is generally considered to have more merit than a drawing; hence the market value of a drawing isn’t deemed to be as great as that of a painting. Certainly it is the view of this artist that a drawing can take considerably longer to complete than a painting, but because it is generally considered to be ‘only’ a work on paper, its value is perceived as lower than that of a painting on board or canvas. And yet the sketches and drawings of great artists such as Leonardo da Vinci, Peter Paul Rubens, Vincent van Gogh, Georges Seurat, Egon Schiele and Gustav Klimt are held in great esteem.

Through exploration, experimentation and studying the work in this book, the reader can find inspiration and guidance. By practising the techniques and following the advice, I hope that you will develop a new confident and creative approach. Indeed the purpose of this book is to build on your existing skills, whatever level they may be, and help you discover new techniques that will lead towards a new creative chapter in your artistic endeavours.

The book presents a logical narrative of suggesting and explaining materials, discussing subject matter, explaining visual language, encouraging best practice and care of materials. You will gain an understanding and working knowledge of techniques by following the practical projects.

There are step-by-step guides describing in detail how certain works have been made, descriptions of different media and processes, sound practical advice, and many examples of work that show spontaneity and creativity made with a passion for drawing in all its forms.

This book is the culmination of my many years’ experience as a student, art tutor, artist, demonstrator and workshop leader. It imparts knowledge gained from a lifetime of experimentation, practice and discovery from trying many different media, in various combinations, and sampling a variety of subject areas and genres.

Everything contained in this book is something I have tried, tested, experienced and learned from.

David Brammeld RBA, PS, RBSA, SPDF, MAFAwww.davidbrammeld.com

CHAPTER 1

GETTING STARTED

This book does not make presumptions about a particular level of ability, about existing knowledge or skills in the reader. It aims to give inspiration and encouragement to the beginner and experienced artist alike.

Model Radio, pastel on A1 paper.

Starting from this premise, it is helpful to start at the beginning, with a level playing field, explaining materials – much in the same way as a story unfolds after introducing the characters and setting the scene. It is prudent, therefore, to assume that everyone has a different starting point, since everyone has a different knowledge and experience base. The book can then guide the reader freely through the many discoveries that lie ahead.

The two separate components of drawing

It is helpful to separate the two main parts to the act of drawing:

Firstly, the technical side, which involves, for example, knowledge and handling of materials, developing and mastering skills, and so on: the practical element.

Secondly, the ‘seeing’ element, which involves training the eye to ‘look’ closely and analyze what it is we want to commit to paper. This is the cognitive element, and is about hand/eye coordination and how we learn to translate what we see. Naturally, we all see things differently. That is not to say that any one view is the definitive one; on the contrary, I want you to discover your own individual way of looking at and representing things, your vision. Your unique take on the world is a valuable thing and will help your work stand out from the crowd.

If you are aware of the distinction between the technical side and the creative/seeing element, it can help pinpoint areas for development.

What do I need to start drawing?

Drawing requires only the simplest and most basic of materials: a pencil, an eraser, a piece of paper, plus either a craft knife or sharpener for the pencil, and that’s about it. These materials are traditional and universally used, as it is natural to reach for a pencil and piece of paper when sharing a thought or explaining an idea to someone. A pencil is possibly the most widely used instrument for markmaking – it’s a familiar tool. From our early days of school we have reached for a pencil to write, scribble, share ideas, make notes, draw or otherwise express ourselves.

I’m working on an A2 pad of smooth creamy heavyweight paper with a mechanical pencil. Different papers give different results – most of my drawing is done on a whiter paper than this, and I also prefer a bit more ‘tooth’. The drawing therefore had a different look and I found I couldn’t achieve the level of tonal control that I normally take for granted. It was a beautifully smooth drawing surface, though.

Moorland Tree in pencil. Sometimes for a change and if the right picture comes along, my response might be to produce a really ‘tight’ drawing: a controlled drawing where I may use just one pencil throughout, with very little eraser work. One of the challenges is to keep the white of the paper ultra clean for the sky, which is very difficult because when you are doing a lot of fine detailed work you need to rest your hand on the surface for control. The point of the pencil should be kept sharp. The drawing needs to be accurate from the very beginning because rubbing out might mark the paper.

This drawing might seem as though it was tedious to work on. Not at all – the slower pace means that marks are more considered, so there was hardly any eraser work involved. It was totally controlled with pencil pressure and layering to build tonal contrast.

Great results can be achieved with just a couple of pencils: a 2B and a 6B, two erasers – a hard eraser and a soft putty rubber, plus a few sheets of good quality cartridge paper or sketchbook. Of course, you will need a board and some clips or masking tape to keep the paper in place, and an easel or table to rest the board on. You will also need something to draw – your subject.

Studio or plein air?

Artists broadly fall into two distinct categories, I think: they are either studio painters – working from photos, sketches, still life, life models and so on (or a combination of these) in a well-equipped work space or at the corner of a kitchen table; or they paint ‘en plein air’ – working outside in all weathers and responding directly to what they see in front of them, whether it is an urban cityscape or the natural landscape.

A sketching trip in winter – seemed like a good idea at the time – but the sunlight and shadows belie the fact that this was a bitterly cold day. Despite the cold fingers I managed to produce some sketches.

It was pleasant enough sitting sketching trees on a well-placed bench in a country park with camera, pencils and hot coffee, as long as the sketches were brief.

In this pastel landscape, the background layers have been built up carefully, creating opacity and variety. The main tree has been established in a loose manner and some drawing has been done to suggest smaller branches. Then it was back to the undergrowth to suggest variety and texture.

The plein air painter is concerned with capturing a moment in time, prevailing light and weather conditions, moving objects like people, transport, cloud formations, the sea and so on. All these elements combine to give an impression of a fleeting moment in time. They are always painting against the clock, battling against constraints of weather or light. They paint with just enough detail to give an impression of what it was like to be there in that location, at that particular moment in time – afterwards that moment is gone, the painting is finished and a new picture calls.

Studio painters have the advantage of having all their materials to hand, a controlled light source and environment, and once they are set up and ready to go they can focus on the job in hand, go for a break, and return sometime later to continue. It’s a consistent, predictable way of working.

It could be argued that the well-equipped and organized plein air painter also has their materials close by, but there will always be uncontrollable elements, such as the weather, intruding on time and focus. Working indoors, the studio painter has the flexibility to paint all day or night depending on preference because they have everything to hand: an image, sketch or still-life composition or life model to work from and a comparatively stable and comfortable environment in which to work. They can work for a few minutes or hours here and there as time permits or finish a work in one sitting.

The joy of drawing or painting outdoors

When I exhibited for the first time in France a few years ago, I had taken various painting materials in the boot of the car. While staying at a château for a workshop, I walked round the grounds one beautiful warm evening, looking for subjects to paint. It was a perfect location.

On a very hot evening in France, I had taken a box of watercolours, water, brushes and a small sketchbook to try to capture something of the beautiful ambience of my surroundings. I simply laid the sketchbook on the grass and enjoyed dribbling paint and sketching, not worrying too much about the quality of the drawing itself. Such is the emotional power of a sketch that just a few simple lines can evoke the moment when looking back. When I see this sketch it brings back the memories of people, place, ambience and so on.

Adding watercolour to these pencil studies in my sketchbook brought them to life. It was good to do this while everything was fresh in the memory. I didn’t make the sketches for any other reason than the enjoyment of looking and drawing.

Here I am in Brittany working on a sketch of a boulangerie. I was planning to do a pencil drawing first, followed by watercolour washes, then pen and ink. I later applied stronger colour as the work progressed. I thought watercolour would be a good medium to enable me to work quickly and spontaneously. There was a time constraint – it was for a competition and the work had to be completed by a certain time.

In the absence of a conveniently placed seat or dry grass to sit on, a lot of my sketching is done standing. I like the feeling of being able to move around a subject easily and quickly, even though it’s a bit more awkward holding the sketchbook in one hand.

It was a great moment just to choose a spot, sit on the grass and sketch whatever took my interest. I worked in pencil first then dribbled some watercolour washes over the top. It was so hot that the watercolour dried rapidly on the paper and I was able to start another painting. It was a memorable moment, and when I look back through this sketchbook I am instantly transported back to that time and place.

Such is the power of a sketch (because of the input to make it), that it can evoke fond memories – the photographs I took at the same time do not connect in the same way. A photo is merely a record of an event, a reference, while a sketch is your own personal response, and therefore has more value.

The materials involved were very basic. I had a small bag with a box of watercolours, a few brushes, pencils, small sketchbook and a plastic container for water – very lightweight and not much set-up time involved. A few splashes of approximate colour over the sketch made all the difference to effectively capture the scene.

Materials to begin with

The beauty of drawing is that you don’t need a lot of materials or a big budget to get started – just pencils, sharpener, eraser and paper and you’re off.

Some pencils to draw with, a craft knife or sharpener to keep them pointy, an eraser to make adjustments with, paper to draw on – it doesn’t get much more simple or basic than this. It’s all you really need to go sketching.

Pictured below are some basic materials to get you started, but as with most things it is always best to buy quality materials from reputable manufacturers. If you buy the cheapest pencils and the cheapest paper, you will not get the best results and may end up being disappointed or disillusioned by the outcome. And you will be denying yourself the opportunity to fully experience the subtleties and different qualities of the materials and to show your abilities to best advantage.

During art classes, I have seen students bring along a cheap pad and pencils – either because they are on a tight budget or simply didn’t know what to buy – and start to draw. Later, when I was giving feedback I would look at the drawing and see that the poor quality pencils combined with cheap paper meant that the student was ultimately disappointed with the result even though they may have had good ability. I would then demonstrate how a good pencil combined with quality paper worked so much better and they then realized that it was false economy to buy too cheaply. Buy the best materials you can afford to show off your skills to the best advantage.

Getting started

Pencils: To start with, work within the range of HB to 6B. In practice you should be able to do most things with just a 2B and a 6B. Avoid the harder ‘H’ pencils at this stage. They are fine for detailed technical work.

Erasers: Choose a good quality ‘hard’ eraser, and a ‘putty’ rubber. The hard eraser is for general work, the putty rubber for softer, more subtle work and tidying.

Sharpeners: Either a pencil sharpener or craft knife (or both). Some artists like to work with a long shaped point to the pencil. This is better for more detailed work but increases the fragility of the graphite point.

Paper: A sketchbook of either A5, A4 or A3 size, whichever size you are comfortable with (I like spiral-bound sketchbooks as the pages can fold back, making it easier to hold when sketching outdoors). Choose one with good quality, heavyweight cartridge paper – around 200gsm or heavier.

Apart from a subject to draw, this is about all you need. Later in the book, this materials list is expanded.

With this little study of a doorway, I added a watercolour wash on top of the drawing to help separate the door and frame from the rest of the building, purely to help me see it better. Later when I look back through the sketchbook it will give me a little reminder of colour.

Here I’m using a double-page spread in my sketchbook to fully explore this dramatic tall tree shape. Sometimes it’s good to change conventional formats, for example A4, A3 and so on. I really like the potential of this format for this particular subject and it will be added to the list of paintings I must begin… I may do a further study, adding colour, to make sure it will work on a larger scale. To match the proportion of the double-page spread, I would cut down a sheet of A1 heavyweight cartridge paper.

A clutch pencil is versatile for sketching. I have two or three of these in the box with different 2mm ‘leads’ in – 2B is a favourite for general work. A useful feature of these holders is the convenient little detachable sharpener on the end, to ensure you can always have a sharp point. Great for sketching on the move.

Testing the equipment – warming up

Before a drawing session, it’s good practice to do a few warm-up exercises to get used to the pencil, make a few different marks, stretch fingers, loosen the wrist and so on.

Before a drawing session I often do some warm-up marks – to get the fingers loosened up and also to get the feel of the pencil.

Using an eraser can have surprising effects. Because there is always a different amount of graphite on the paper surface, it’s a good idea to test it beforehand.

I also like to run through a repertoire of warm-up marks. Every time I do this I am surprised to discover new marks, so it is worthwhile doing a few quick exercises. Do this before you start your drawing and you will have broken the ice and got over making those sometimes-tentative first marks of a drawing.

I do some hatching and scribble marks, produce some flat tones, then use an eraser to cut back into these marks. This is time well spent and is actually quite enjoyable.

Produce a rough sketch

For relaxation, I will often grab a few photos, pick up a sketchbook and a mechanical pencil and just start working my way through them. I search for some good lines, interesting shapes, and compositions for future projects. It really doesn’t matter how finished the sketch turns out as I am just really exploring the subject to see if it interests me enough to continue with a larger, more ‘finished’ work. I may work my way through a pile of images in this way, discover one or two where I can see possibilities, then do further studies of different parts of the same subject.

A derelict building study from my sketchbook. I am fascinated by crumbling render on buildings, when the brick structure beneath becomes exposed. Here I wanted to understand the details of the window. It was one of several studies I made before making a large graphite drawing and small acrylic painting.

Sometimes I pick up a photo just to follow a few lines or shapes or perhaps to examine a few bits of interesting detail, then move straight onto the next photo and repeat the process.

A couple of quick tree sketches, to help satisfy my endless fascination with tree shapes. They are always interesting to draw – always different. The pages are buckled with the effect of washes, and there is some offset where one drawing has rubbed off on the other, but it doesn’t matter – the drawings are just for my own reference.

This is enjoyable – there is no pressure to finish the drawing or to do the whole picture – and it gives thinking time to proceed with an idea. New ideas form quite easily if you allow yourself a little time to be immersed in the subject.

Taking it further

Having made several rough sketches, some will have worked out better than others and warrant further exploration. Selecting one that works well, I will draw it again, strengthen shapes and add more shading to understand the composition better, making darker and heavier lines. I might increase the tonal range to give a better visual representation of the picture.

Which pencil should I choose?

Ideally, the first marks you make on a drawing should be exploratory, and therefore soft and light to act as guidelines. As the drawing develops, the marks can become more confident and bolder. I think it’s useful to keep these construction lines right up to the end of the drawing – they create visual interest and show the actual process of making the drawing – but if they bother you or look untidy then use a putty rubber to clean them. Personally, I like to see how a drawing or painting has been made, so I will often leave these exploratory marks in. The artist Euan Uglow (see the catalogue for his retrospective Controlled Passion: Fifty Years of Painting, Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Kendall) was famous for making many extra marks in his paintings to help line things up and position them. These markers became an integral part of the painting.

Using an HB or 2B to start with, the drawing is less likely to get out of control. Of course you can make similar soft marks with a 6B, but if you are not able to control the lightness of touch needed then you may discover that you are making heavy marks too soon and the drawing quickly gets out of shape. The 6B will also wear down more quickly, losing its sharpness. An HB or 2B pencil will hold its point for longer.

It’s important to understand the properties of the pencil you are using so you can see why it’s behaving in a certain way.

What is the difference between a soft or hard pencil?

Graphite pencils use a mixture of natural graphite powder mixed with different amounts of clay to give grades of softness or hardness. The resulting paste is extruded and dried, then sandwiched between two halves of a wooden sleeve to create a convenient writing and drawing instrument – the pencil. Major manufacturers such as Faber Castell, Derwent and Staedtler offer excellent quality pencils. Over time you will discover your own favourites.

Canal scene. This derelict canalside factory is one of my favourite subjects. I have sketched, photographed and painted it many times over a period of years and changing seasons. One of the things about returning to this place is that it is always different: the foliage changes depending on the season and derelict buildings change too, as nature takes hold and tries to reclaim them. I used a 6B pencil for all the drawing, and used a doublepage spread of an A4 sketchbook. I always tend to draw larger than the paper allows, so the option of the extra space was useful.

Lonely Tree, pencil on 300gsm A1 cartridge paper. This drawing was always intended to be quite a ‘tight’, controlled drawing with lots of detail. I thought it was a beautiful, characterful subject and very good to draw. It was very satisfying to work on the texture of the bark and then the strong shadows cast by the small branches that followed the contours of the trunk.

I find a mechanical pencil ideal for small sketchbook work. Here I’m working on a densely ivy-covered old tree and the fine (0.7mm) point is a perfect tool to create an impression of the busy textures. I used a scribble technique that I thought captured something of the lively nature of the subject.

Pencils have a rating stamped on the end that specifies their grade, for example 6B, 3H, B or HB, but what do these codes mean?

HB is a universal, standard pencil – the norm. It is a general all-purpose pencil, widely used in schools and offices.

Soft pencils start at 2B and gradually get softer towards 9B. So the greater the number of BS, the softer the pencil. Softer pencils wear down more quickly, thereby losing their point, so need regular sharpening to maintain consistency. For normal sketching and drawing it is sufficient to stay within the 2B–6B range depending on your preference. These grades will suit most needs.

Hard pencils start at H and get harder up to 5H. F stands in the middle of BS and HS. Hard pencils are used for more technical work as they are capable of fine, light marks that are necessary for precise design work. Harder pencils keep their points longer but will not be able to give a dark tone.

The range from hard to soft runs like this: 5H, 4H, 3H, 2H, H, F, HB, 2B, 3B, 4B, 5B, 6B, 7B, 8B, 9B. Some manufacturers offer different ranges, and some do not offer a complete range.

Which sketchbook or paper should I choose?

A sketchbook is a useful way to keep your sketches, drawings and ideas together in order and will make a great source of reference material as it grows. It is also a record of progression and development of skills and ideas. Choose either spiral-bound, stapled or glued and stitched pages in popular A5, A4, A3 or A2 sizes or a variety of square or rectangular formats, depending on your preference. With a spiral-bound, hard-covered sketchbook it is easy to fold the book back on itself for convenience and robustness, and it is possible to continue a drawing across the spine although there will be a gap and the metal spiral in the middle. With a sketchbook with glued or stapled pages there is a less pronounced division, but they are a little more difficult to hold properly if you are standing while sketching. Choose a good quality cartridge paper – heavier weight papers will take ink and wash, watercolour, pen, charcoal and so on as you begin to experiment with different media.

Terraced Houses, Backs. Here I have decided to develop a pencil and pen sketch by adding some watercolour. The colours are not accurate, but it enabled me to see if the subject would work as a larger painting. Even the weakest of washes of colour can add interest to a study. The perspective was a challenge, as well as the variety of colour in the different blockwork and brickwork.

I am exploring the possibility of this dramatic windswept tree for a possible painting, having applied some acrylic washes over a pencil sketch. The inspiration was a group of windswept craggy trees clinging to a remote rocky hillside in the Peak District. The sky was suitably threatening. Whenever I see this sketch it reminds me of being there. I still haven’t got around to doing the painting, though.

If you choose loose sheets of paper, you will need a drawing board or some stiff card and some clips or masking tape to keep them in place, and a folder to keep the work together later.

Note: If you are working with watercolour or ink in a sketchbook you will have to wait for it to dry before turning the page, which can be frustrating and time-wasting especially if working en plein air. So you may want to have a few loose sheets of paper to hand or a couple of sketchbooks on the go so you can continue to work on more drawings.

Erasers – hard and soft

Ideally, you will need both a ‘hard’ eraser and a soft ‘putty’ rubber. Each has its own special qualities. A normal, universal hard eraser is fine for making general adjustments to your drawing. A putty rubber helps with more subtle graphite removal at the lighter end of the tonal range, for instance working on fluffy clouds. Try erasers from different manufacturers as they do vary a lot. I have many erasers in the box, each one having different qualities: some can be quite rough or ‘gritty’ when used and can damage the paper surface; some are more effective than others at removing heavy layers of graphite; some have different shapes. So be prepared to sample or buy a few different sorts till you find some that you are happy with.

This is a treescape in graphite and tinted graphite on A1 paper. It is a busy scene with many interwoven branches and I am using an eraser to help cut a branch through the trunk. In effect I am drawing with the eraser. I will need to use a pencil to help lift the branch away from the rest of the tree.

What shall I draw?

The short and best answer is: anything and everything!

You have your sharpened pencils, paper and erasers and are eager to get to work to produce great drawings and are wondering what to draw. It’s a good idea to start drawing things that are in front of you and that you are familiar with – things you like – rather than working from a photo, as this will be more valuable in helping to understand form, scale, proportion and so on. But, if you find it easier to work from a photo, try not to just copy it.

Some people enjoy the challenge of producing a drawing a day, or doing at least some drawing on a daily basis. It doesn’t matter how long you spend on the drawing, but regular practice will ensure a good steady progression of skills. The message is really just to keep drawing as often as you can – it is all worthwhile experience.

As soon as you start to draw familiar everyday things – things around the home or garden, for instance – you will begin to view them in a different light. We are so used to looking at familiar things that our brains quickly assign this information to memory, and we need just a millisecond to recognize them again when next we see them. So we have become used to ‘seeing’ things with our brains rather than with our eyes. If we try to draw familiar things we scrutinize them more closely and start to understand more about how they are made. New discoveries about familiar things can be surprising.

Two-page landscape study in pencil. With this study, I had made the initial pencil drawing because I liked the dramatic, unusual composition. When I looked through the sketchbook some time later and rediscovered it, I had the idea for a painting. So I took it a stage further and added a watercolour wash to see how it would look.

This drawing is one of a series taken from photos I took when visiting a motorcycle show. I was fascinated by the shapes and textures of the patina – it wasn’t shiny and new. I had the idea to do an impressionistic drawing that suggested the complex details rather than elaborating too much.

Something different: I thought this sheep would be interesting to draw as I haven’t done much drawing of animals. It was a challenge, but it is always good to try something new. The curved, textured horn gave some structure, as there was not a lot of clear detail to focus on. I enjoyed trying to capture the woolly texture in pencil.

With this little observational plein air study in pencil, I was interested in the shapes of the stonework and discovered, interestingly, that there was once a large doorway or arch that had been filled in and modified at some point earlier in its history. It is so interesting when these little discoveries become apparent, because you are taking the time to look properly and allow some thinking and looking time. I started the sketch in front of the building, then took photos to enable me to study the detail at my leisure.

Each different subject is a new challenge. If you choose a subject you know and love, it is a good starting point to maintain interest and build confidence. Later you can try the unfamiliar to widen your repertoire and test yourself further. So start drawing what you know, get to know it more thoroughly by drawing it from different angles, then move on to other subjects. You will find that certain subjects work better than others, so while it is good to recognize this, it is equally important to attempt new subjects. I think each of us has an affinity with one or two subject areas that enable us to produce better results. For me, urban and natural landscapes work best.

I am also fascinated by portraiture, but the results always fall short of my expectations. It doesn’t put me off though, as I love to try to capture a likeness of a person. I think it’s one of the ultimate challenges and therefore most rewarding if it works; however, frustratingly, it sometimes doesn’t come off as well as other subjects.

The more often you use your sketchbook to draw, doodle or just to look through, the better. Make it a part of your daily activity. Drawing is one of those things where the more you do, the better you get.

A sketchbook is your best friend

I always keep several sketchbooks on the go and use them regularly whether for new drawing or for reference. Using a sketchbook regularly is a great way to check progress and to collate thoughts and ideas. I can develop themes and interests, and go back to them again and again.

Sketchbooks with good quality cartridge paper will handle a range of different media. Sometimes there is a trade-off between choosing paper that is too heavy and one that is too light and buckles too easily when wet. Some artists have personal favourites – whether it’s creamy smooth paper or heavyweight white – and always choose the same brand, which is good for consistency. This means that they have a uniform collection of books that will form a unique archive to look back on.

One of the most valuable things that an artist can acquire over time is a collection of sketchbooks. It is always interesting to look back at ideas or studies – often these can lead to other avenues of exploration, or an affirmation of an existing pre-occupation.

Using a double-page spread in an A4 spiral-bound sketchbook, I enjoyed the freedom and expressive potential of making a direct sketch in pen and ink (without any underdrawing) of this old derelict pub. The ink smudged a little because I turned the page too quickly to do another sketch, but it didn’t matter. When I looked back on the drawing, I decided to add some loose watercolour washes to distinguish the building from its surroundings.

A quick townscape sketch: I found this composition interesting as there was dramatic perspective in the old snooker hall on the left leading to the frontal aspect of the row of shops on the right. I did some directional shading, which helped define some of the planes.

Seeing negative space: After making this pen and ink study of derelict houses on site and once I got back to the studio and was looking through my efforts, I decided to add a simple blue wash to reinforce the negative shape of the sky. It instantly made the buildings more visible, separating subject from background and making the composition clearer. Often, looking at negative spaces helps to ‘see’ the main subject more clearly.

Two pages from an urban landscape sketchbook. On the left are some studies of details, on the right a colour-washed pencil sketch to see if this subject would work as a painting. The addition of a few simple colours helps to separate the different elements.

Keeping two sketchbooks on the go is a good idea: an A4 or A3 pad for general work, and maybe a small A6 pocket-size book to keep with you all the time. You can work between the two, transferring ideas from one to the other. You will be surprised how often opportunities for sketching present themselves during the course of a day. Drawing little and often is great training.

My own collection of sketchbooks has grown over the years to become an invaluable resource, something that I look through regularly. It can act as a personal diary, especially if you date the work and add notes as you go.

Beginners’ mistakes

Relying too much on an eraser

Many times when I have watched beginners start a drawing, they make a few marks then immediately rub them out and start again. This process is repeated over and over, and it is a wonder that the drawing ever gets going. They are convinced that every mark they make is the wrong one. But how can these marks be ‘wrong’ until other marks have been made alongside against which to judge them?

It is good practice to get most of the subject down first, block it all in with light, exploratory construction marks. If the pencil marks are light, relationships can be made with other marks, and the drawing can start to take shape and move forward, evaluation can take place, and any adjustments made to proportions, perspective, composition and so on. If the construction lines are light enough, there is something to work with.

A couple of pages of studies of doorways made during a trip to France. It’s quite interesting looking back on these sketches to see the diverse range of subject matter that I found and wanted to draw. In this instance I was using the sketchbook as a daily diary. I added colour to the day’s sketches while everything was fresh in my mind.

Drawing too heavily too soon

Making marks that are too strong too early doesn’t leave much room for adjustment. If the drawing has to be tweaked, it may be difficult to remove heavy marks cleanly. A drawing needs a variety of mark-making, both in terms of weight and thickness. For example, subjects in the distance need to be drawn lighter than the main subject. Marks in the foreground can be stronger and bolder.

Detail comes later

Some people can be preoccupied with focusing on detail too early in the drawing, sometimes before the main shapes have been established. Detail only works if it is in the right place – it can only work over a sound underdrawing. If, when drawing a house, the windows are drawn perfectly, but are too small or too big in relation to the house, then visually they won’t work. Likewise, it is pointless drawing in the bricks before the main proportions of the house are established. It’s easy to say ‘forget the detail for now’, but zoning in on detail too soon can add confusion and ultimately create extra work because if it’s in the wrong place at the wrong proportion it will have to be redrawn later.

Try to see big shapes first

When confronted by a scene, whether it’s inside or out, there will be a lot of extra ‘clutter’ to confuse the issue. Try and see the big shapes first; keep it simple. Some artists use a viewfinder to help select the content, in the same way that a camera screen or viewfinder helps frame the picture.