9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

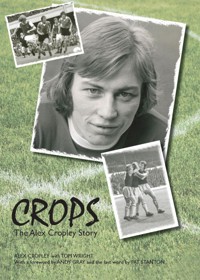

A nippy sweetie, he was always moaning, but that is often the sign of a great player - a real determination to succeed and a refusal to settle for second best. PAT STANTONI used to flinch when Studs wound up for a challenge and he feared no one as he sometimes threw his whole body into a tackle. That meant we also spent too much time together in the treatment room. ANDY GRAY Alex Cropley had just left school when he was picked up as one of Scotland's latest football talents. Signed to Hibernian aged just 16, Cropley soon made his name as a player on the team's legendary Turnbull's Tornadoes side. Over the 1970s, he played for Hibernian, Arsenal, Aston Villa, Newcastle United, Toronto Blizzard and Portsmouth, before a number of injuries forced him off the pitch. From a football-mad kid playing on the streets of Edinburgh to a member of the Scottish national team, his career epitomises both the aspirations and the bitter disappointments surrounding the game on the pitch. Cropley's tale of his time on (and off) the pitch isn't just the tale of one man's odyssey, however, but rather offers a glimpse into the footballing landscape of the time, with an engaging and often wry depiction of the larger-than-life characters who went on to become the greats of Scottish football. A frank but warm-hearted account of the hopes and despair of the great game, Crops will delight football fans of all ages.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 395

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

ALEX CROPLEY played for Hibernian, Arsenal and Aston Villa football clubs, among others. Born in Aldershot to a family of semiprofessional football players, he also played for the Scottish national side in the 1970s. Two dreadful leg-breaks resulted in many English First Division games being missed before his move to Aston Villa. Affectionately known as ‘Studs’ at Villa because of his ferocious tackling, Cropley retired due to injuries during his tenure there.

TOM WRIGHT was taken to his first game aged nine, a friendly against Leicester City at Easter Road in February 1957. Little did he realise that football, and Hibs in particular, would become such a major influence in his life from that day on. Wright has now been a Hibs supporter for over 50 years, and has the scars to prove it. Previously the Secretary of the Hibs Former Players’ Association, Wright is now the official club historian and curator of the Hibernian Historical Trust. He is the author of Hibernian: From Joe Baker to Turnbull’s Tornadoes and The Golden Years: Hibernian in the Days of the Famous Five.

CROPS

The Alex Cropley Story

ALEX CROPLEY with TOM WRIGHT

LuathPress Limited

EDINBURGH

www.luath.co.uk

First published 2013

ISBN: 978-1-908373-97-7

ISBN (eBook): 978-1-909912-65-6

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

© Alex Cropley 2013

To my mum, brother Tam, my wife Elizabeth and family

Contents

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

FOREWORD BY ANDY GRAY

PREFACE

1 In the Beginning

2 The Professional Game

3 Willie MacFarlane and Turning Full-Time

4 A European Debut and Injury Heartache

5 Eddie Turnbull, a Scotland Call-up and a Meeting with Sir Alex

6 Turnbull’s Tornadoes

7 Enter Joe Harper and a Penalty Disappointment in Europe

8 A Dream Move to Arsenal and Leg Break Nightmare

9 Terry Neill, More Leg Break Heartache and Life at the Villa

10 Yet Another League Cup Final Triumph

11 In Europe with the Villa and a Clash with Ally Brown

12 A Brief Return to Action

13 Newcastle, Toronto and a Nightmare at Portsmouth

14 A Sodjer’s Return, Retirement and the Story So Far

Picture Section

MY GREATEST TEAM

ALEX CROPLEY: TEAM APPEARANCES

THE LAST WORD BY PAT STANTON

Acknowledgements

I am particularly grateful to both Andy Gray and Pat Stanton for kindly agreeing to write the Foreword, and the Last Word for the book. Also for the assistance of the Arsenal Official Historian, Ian Cook, who supplied me with details of the games I played for the club, and particularly the Aston Villa fanatic Colin Abbott who couldn’t be more helpful in supplying me with details from my time at Villa Park.

All the photographs in the book are from my own personal collection. Every effort has been made to locate image copyright holders and to trace sources of media quotes.

Foreword

I FIRST BECAME aware of Alex in the early ’70s. I had joined Dundee United in the summer of 1973 and Alex was already impressing people with what he was doing on a football pitch. It wasn’t just the wand of a left foot that he had but the way he went about his business that impressed me. He was barely nine stone, dripping wet, but feared no one. Was he too brave for his own good? He was. Did the way he launched into tackles against people twice his size cost him dearly regarding injuries? It did. But would he have changed the way he played? No, he wouldn’t.

It was no surprise to anyone that an English club came calling, and what a club. The Arsenal. I’m sure he left as we all did in those days with dreams of great things to come. In the very physical league that was the English First Division it never did work out the way Alex would have wanted, and not for the first time he would miss too many games through terrible injuries.

Because of that, an up-and-coming team – Aston Villa – was able to tempt him to Villa Park. From the first day he arrived I loved him. He was even better than I thought and I very quickly found out that although our personalities were very different we shared a couple of important traits, we loved the game and we hated losing – and I loved that about him. We got very close and lived only a few hundred yards from each other so often went into training together. We enjoyed each other’s company as well and often socialised together. I was also responsible for the nickname he had at Villa – Studs. I used to flinch when Studs wound up for a challenge, and he feared no one as he sometimes threw his whole body into a tackle. That meant we also spent too much time together in the treatment room.

For a man who suffered some shocking injuries, his desire to get better and slog his way through numerous recovery programmes to get fit to play again was inspirational to anyone who came into contact with him.

By the time I left the club in September 1979 we had shared some great times. The winning of the League Cup was oh so special. It was a marathon campaign where Alex played a huge part, but I think that even better than that was one Wednesday night in December 1976 at Villa Park when the mighty Liverpool rolled into town on their way to winning the Championship again. They were full of top players but we were making a bit of a stir in the league with a promising start. By the time we walked off at half time we were 5-1 up and Alex had been majestic. Apart from crashing into tackles and ruffling a few feathers, he was in magnificent form in the game. Totally dominant in the midfield with his range of passing, and when he went off just before the hour with a groin strain he received one of the biggest ovations I’ve ever heard.

He was eventually going to succumb to his injuries, but I’ve loved having Studs as a teammate, but more importantly as a friend; and the one thing I am glad about is that I have never had to feel the force of a fully committed Studs tackle. Somehow, like many before me, I think I would have come off second best.

Love you, wee man.

Andy Gray

Preface

I FIRST MET Alex Cropley over 15 years ago, when I asked him to sign a Hibs jersey that was to be auctioned at a charity event. We got on fairly well and he would regularly pop into my shop for a cuppa and a chat about football, the conversation invariably turning to Hibs.

Over the years he would recount countless stories of his time at Hibs, Arsenal and Aston Villa in front of a very enthusiastic listener. It was clear that he still retained great affection for all the clubs he had played for, and it was my idea that we should write a book about his time with some of the biggest sides in the game. The modest Alex however was unsure, convinced that no one would be interested in him after all this time. After some consideration however, and a bit of persuasion from me, he eventually agreed, and this book is the result of many meetings spanning several months.

As a keen Hibs supporter I have many fantastic memories of the great Turnbull’s Tornadoes team of the early ’70s in which Alex played such a prominent part. The side was packed full of incredible players and personalities, but with all due respect to the others, for me Alex stood out, his energetic and enthusiastic style of play allied to his educated left foot immediately taking the eye, and to my mind, even in the very early days, he was destined to go right to the top. Unfortunately, as good as he was, injury probably prevented us seeing him at his very best, particularly as he matured in later years. Who knows just how many international caps he would have received had it not been for this. However, it was not to be, and he retired almost obscenely prematurely in 1982, aged just 31, to run a public house in Edinburgh which was a popular meeting place with supporters before and after games at Easter Road.

Although he remains a member of the Hibernian Former Players Association, the modern game holds little appeal for Alex and today he rarely attends games at Easter Road, preferring to watch his football on TV.

Alex Cropley is genuinely one of the nicest people I have ever met. Unbelievably modest and unassuming, one would go far to find anyone who has a bad word to say about him, and I consider it a great privilege to be regarded as a friend.

Tom Wright

CHAPTER ONE

In the Beginning

HAVING SPENT MOST of my life in Edinburgh, I consider myself as Scottish as the next man but I was actually born in the army garrison town of Aldershot in the South of England on Tuesday 16 January 1951. Some people are under the impression that my dad John was in the army and serving at what was then the largest military camp in the country, but in fact he was a part-time player with the local league side Aldershot, working as a moulder in a nearby foundry during the day. Aldershot had been formed as early as 1926, but since then they had rarely risen above the lower reaches of the old Third Division South. The only exception was during the Second World War when, taking advantage of the guest regulations that allowed them to call on many of the international players who were serving at the nearby army camp, they had assembled what is considered to be their greatest side. Players included Stan Cullis, Joe Mercer, Scotland’s own Tommy Walker and Tommy Lawton, the latter ending the war as the third top goal scorer in the country.

In Scotland my dad had played for the well-known juvenile side Portobello Renton before moving on to Tranent Juniors. The name juniors is actually a bit of a misnomer as it had nothing at all to do with youngsters, but was in fact a junior, or semi-professional side. At that time many top professional players would finish their career playing in the junior ranks, which by all accounts was a hard league that soon separated the men from the boys, and would have been an extremely difficult baptism for a young player who had previously been accustomed to the lesser pressures of amateur football. Apparently my dad had once played against Eddie Turnbull in 1946 when my future manager at Hibs was with Grangemouth junior side Forth Rangers.

Dad was signed for Aldershot by manager Billy McCracken in 1947 against the wishes of my grandad, a former amateur goalkeeper, who was convinced that his son was then on the verge of winning a Scottish junior cap. McCracken, a former Newcastle and Northern Ireland player, is said to have been directly responsible, because of his ‘cunning tactics’, for the change in the offside law in the 1920s that now required only two players to be between an opponent and the goal, instead of three as before. Ironically, McCracken would be replaced in the Aldershot hot seat in 1950 by Gordon Clark, a man who was to have a major part to play in my signing for Arsenal a few years later. There was yet another future Arsenal connection at Aldershot at that time in trainer Wilf Dixon, who would later become coach under manager Terry Neill during my time at the north London club.

Although tall and slim, by all accounts my dad’s lean physique was deceiving, and I have been told that he was an extremely hard, sometimes ruthless player, who in the words of the old saying, would ‘kick his granny’. Later he would instill in my brother Tam and me that the harder you went into a tackle the less chance you had of being injured. It was advice I would often pay heed to, particularly during my professional career, sometimes to the detriment of my physical wellbeing.

Born in Lorne Street, my dad was considered to be a ‘real’ Leither, and he attended the local Lorne Street primary school before moving on to Bellevue secondary. In those days most ordinary people rarely travelled very far and he met and married my mother Margaret Lyle who was born in Albert Street, just a few hundred yards away. They were married soon after the war before moving south to Aldershot, and the tidy one-up one-down two bedroom council house in Aldershot that actually had its own bath, must have seemed like a million miles away from the claustrophobic, grimy and soot stained tenements of Edinburgh. It was while they were in Aldershot that my mum found that she was expecting my brother Tam, who is two years my senior. In a rush of patriotism, they were determined that their first child should be born in Scotland, and my mum returned to Edinburgh on her own to have the baby. I have been told since that when I came along a couple of years later, although they both wanted me to be born north of the border like my brother, my mother couldn’t be bothered making what in those days would be a long and tiring journey home, hence my English birthright, and later at Hibs the nickname ‘Sodjer’, which is the Scottish derivative of Soldier.

I have very few memories of Aldershot except that we lived in a very quiet street, the one-up one-down houses all with their neat and tidy front and back gardens. My only other memory is of walking to the end of the road to meet my dad on his way back from work and being given a ride back home on the bar of his bicycle. At that time my dad worked at the nearby Farnborough air base. The base had been home to the Army Balloon Factory in the early years of the century, and it was from here that Samuel Cody famously made the first ever British aeroplane flight in 1908. No doubt my dad would have been working at the air base during September 1952 when an experimental de Havilland Sea Vixen aircraft crashed into the crowd during that years air show, killing 31 including the two crew, the horrific event captured by a newsreel camera team.

After seven years with Aldershot and 172 appearances, Dad signed for Weymouth. I don’t think he cared too much playing for the Southern League side, and with the family keen to return to Scotland, we moved back to Edinburgh around 1954 when I was about three years old to live with my gran in Albert Street in the heart of the city. Albert Street was only a few hundred yards from the old boundary between Leith and Edinburgh before the two had amalgamated in 1920, and just a stone’s throw from Easter Road Park, the home of Hibernian Football Club. I can still remember seeing for the first time one of the floodlights that towered over one end of the street, never dreaming for a minute that one day I would play for the club.

For me Albert Street was a completely different environment from what I had been used to, and although I was extremely shy and a newcomer from England to boot, I soon managed to make a few friends and can remember my short time there as being absolutely fabulous. Like all kids at the time we were without a care in the world, and would play from morning to night in the street, our games in those less congested times only rarely interrupted by the passing traffic.

My brother Tam and I both attended the local Leith Walk primary, the same school as my mother had attended as a child, and it was at Leith Walk that I first set my eyes on a competitive game of football. Although it was only a playground game between pupils at lunchtime, I can still vividly remember how captivated I was and can still recall that the ball was green and blue in colour. It was at that exact moment that my lifetime passion for the game was born. Although I was shy, sometimes painfully, I soon made new friends from school and we would spend all our spare time playing football in the back greens of the tenements. At that time I was never without a ball, and like many other boys, every available minute at school would be spent kicking it around the playground until one day someone smashed one of the school windows, resulting in an immediate ban by the teachers. Not to be outdone however, my mum knitted me a woollen ball, as did some of the other mothers, and we were allowed to continue with our playground passion.

After a year or so living with my gran, my family received the keys to a brand new two bedroom council house at Magdalene on the outskirts of the city, the wide open spaces a world away from the narrow confines and cobbled streets of the city centre. Magdalene was bordered by Niddrie and Bingham, and also what we considered to be the much posher Duddingston. The scheme had been built specifically to accommodate the overflow from the centre of a city that was then in the middle of a major slum clearance campaign that had seen many of the old unsanitary and often uninhabitable 19th century dwellings demolished.

For a youngster, Magdalene was a new found world of magic and excitement. The surrounding cornfields and running burns formed part of a magical playground, and as one of the first families in the scheme my new pals and I would often spend hours playing in some of the yet to be completed buildings.

Although we now lived several miles from the city centre, my brother Tam and I still attended Leith Walk school and we would catch the early morning bus along with our mother who was then working at Fleming’s, a confectioner’s warehouse in nearby Albert Street. Dinner, usually consisting of soup, my favourites of either mince and tatties or stovies, finished off with a pudding, would be eagerly gulped down at my gran’s house before hurrying back to school to play football in the playground. With what we had just eaten it was a wonder that we could walk never mind run.

By this time I was gaining a little bit of a reputation as a good player. Some of my schoolmates had started calling me ‘Cannonball Cropley’, although I still don’t know if they were being serious or taking the mickey, and I was usually amongst the first to be picked for our unorganised teams, either in the playground or the local park.

Although I was football mad and rarely seen without a ball, other pursuits did occasionally occupy my young life. Tam and I joined the 37th Lifeboys based in the local St Martins church in Magdalene, sadly now demolished, where we were also encouraged by our parents to attend Sunday School. Sunday School didn’t last too long as it tended to interfere with our football in the local park. There were also the regular jaunts on the number 5 or 44 bus from Magdalene, we tried to avoid the number 4 as it travelled through Bingham, an area we considered to be quite rough, to either the Salon or Playhouse picture houses in Leith Walk. The Salon usually featured two cowboy pictures and loads of Walt Disney cartoons, while the Playhouse was a little more upmarket showing most of the current films of the day. After the pictures there would normally be the obligatory bag of chips soaked with brown sauce, before catching the bus home. At that young age who could have asked for better?

On Friday evenings during the summer months Tam and I would often be taken by our parents to watch the Edinburgh Monarchs racing at Old Meadowbank. When we got a little bit older we would go ourselves, often managing to sneak in without paying. Speedway had been suspended during the war, but had since re-established itself almost to its pre-war popularity and during the ’50s and ’60s Meadowbank was capable of attracting crowds of well over 10,000. Many would watch the races from the ramshackle grandstand that had previously been used by St Bernard’s football team at the Gymnasium in Stockbridge before being taken bit by bit to Meadowbank just after the war. I eventually became so keen on the sport that in 1967, some friends and I made our way to Wembley to cheer on local rider Bernie Persson, one of the first riders from a provisional club to compete in the World Championships. Unfortunately, the Monarch’s rider failed to impress, but we did get to see the famous Swedish rider Ove Fundin, the ‘Flying Fox’, win the World Championship for a fifth time. Fundin is still regarded by many to be the greatest rider of all time and has since had the Speedway World Cup named in his honour.

Strangely, although my dad was a keen Hibs supporter as a youngster, and living not that far from the ground, we were rarely taken to see Hibs play at Easter Road, although I can recall the time during one game my dad telling us that he knew Bobby Combe, one of the Hibs players that day. Scottish international Combe had signed for the club in 1941, the same day as the legendary Gordon Smith, becoming a mainstay in the great Hibs side of the late ’40s and early ’50s that was led by the fantastic Famous Five, and would go on to give the Easter Road side 15 years of sterling service. Combe had a grocers shop in Leith Walk, and whether my dad knew him personally or only as a customer I don’t know.

Probably influenced by the Friday night speedway at Meadowbank, another popular pastime with many of the young lads in Magdalene at that time was cycle racing. What had originally been just a disorganised meeting of boys racing with ramshackle bikes on a bit of wasteland, some without brakes, gradually developed into a far more organised affair. One day, my brother Tam who was a really keen rider, along with some of his pals armed with shovels, dug out an actual track on some waste grassland. Later, a group of parents approached the local council who surprisingly agreed to construct a proper track, and soon we would be racing against teams from other areas, some of our bikes painted in the Monarchs’ colours of blue and gold. The events eventually became so popular that on a good night they were capable of attracting a big crowd.

Although I wasn’t as keen as my brother Tam I normally took part in the races, but football remained my main passion. Usually failing to take a great interest in the ongoing proceedings, I would play about with the ball that I always carried, race my four laps when required, then return to play with the ball. My brother however took it far more seriously than I did and on one occasion even travelled south to compete in the individual championships. I believe that there are still photographs circulating on the internet of the Magdalene track, one featuring my brother, and another of both of us racing against each other.

A defining moment in my young life was the day the teacher asked us who wanted to be in the school football team. Because there were so many volunteers, trials had to be held, but there were no nerves on my part. I had played many times with most of the others in the playground, knew I was better than most, and took selection for granted. However, I can still remember the thrill of being handed the blue and green striped jersey with a large number ten on the back before the first game for the primary school, my first ever outing in a competitive football match. I don’t think we had a particularly good team although we did manage to reach the semi-finals of a cup. On the day of the game, against Drumbrae at Warriston, it seemed as though the whole of both schools had turned out to watch us, as had my mum and dad and presumably most of the other parents. For me the day would turn out to be an unmitigated disaster. Almost sick with nerves before the game, once in front of what was, as far as I was concerned, a huge and intimidating crowd, I was totally overawed and failed to do myself justice. In fact I was absolutely useless, contributing less than nothing to the proceedings, and we ended up losing 3-0. I don’t know what my mum and dad really thought about coming all that way for nothing, but I can still remember them trying unsuccessfully to cheer me up all the way back to Magdalene. I must have been doing something right however as my name had started appearing in the local papers, but infuriatingly, they would forever be getting the spelling wrong. It would usually be Croffee, Croppy or Croply, and although it was disappointing, I consoled myself with the thought that at least I was getting noticed.

Luckily the summer holidays were just around the corner, the seven week break quickly helping to put the humiliation of the semi-final out of my mind. Although it was obviously not the case, looking back it really did seem as though it seldom rained during the summer break, and long days would be spent playing football in the park, only your stomach telling you when it was time to go home for your dinner.

All too soon the summer holidays were over and it was time to move on to secondary school. For me that meant Norton Park, which was situated only a few hundred yards from Leith Walk school and directly adjacent to the Hibs football stadium. I can still vividly remember that first day standing outside the school gates absolutely petrified, watching in horror as many of the other new starts were made to run the gauntlet of much older boys, kicked as they passed along the line. That did it for me, I was no fool and decided to stay outside the playground until the bell rang. My brother Tam was also at Norton Park at that time, but he was with his own mates and didn’t seem very concerned about me, although I suppose that would be a normal reaction from someone that bit older.

I was not particularly academic and didn’t care too much for lessons, although I quite enjoyed history, geography and PT, all I really cared about was football and speedway. Being so close to the Hibs ground we would regularly see many of the players including goalkeeper Willie Wilson, John McNamee, Joe Davis and Pat Stanton arriving for training. A few years later I would play alongside Stanton and Davis, but at that time while most of the other pupils were eagerly collecting the Hibs players’ autographs, I was far more interested in the signatures of the speedway riders.

At Norton Park I played for the school team in the morning, sometimes for the year above if they were a man short, and the Boys’ Brigade in the afternoon. The BBs played on shale pitches on the seafront alongside Musselburgh gasworks, which was not a great location for a ball player if it was very windy, but the main problem was that the set-up was very disorganised with the games few and far between. With my thirst for the game, this was not nearly good enough for me.

One day after a game I was approached by Tom Young who was on the committee of Royston Boys Club, who asked if I would like to come along to one of their Under 16’s games. None of my pals were interested in coming with me so I turned him down. Tom persisted however, and I eventually agreed to join the Royston set-up. Although I was still only 14, I often found myself playing against boys much bigger and older than me, but my tenacity and hard tackling, something that had always come naturally to me, allowed me to more than hold my own. After playing for both the school and by then the Boys’ Brigade, Royston was a completely different world. We would actually play with a white leather ball instead of the old worn brown one as before, and even received a cup of tea or orange at half time.

Although I had made many friends at the Boys Club in a short space of time and had enjoyed it immensely, I jumped at the chance to join St Bernard’s Under 16’s, probably because my brother Tam was then playing for the Under 21’s side. Tam was a very good player who could well have gone much further in the game had he put his mind to it. An uncompromising hard tackling right half, I imagine that he would have been a bit like my dad in style. Although he was a bit slower than me he was as hard as nails, but I think he lacked the necessary conviction to go professional. He enjoyed many sports, particularly golf, and it was not unusual for him to play a few holes at six o’clock in the morning before spending the day at work.

At that time St Bernard’s were a nursery team for Chelsea and I can still remember the pride I felt the day we got to wear the full Chelsea strip. The feeling didn’t last long however. The following week the entire kit was handed over to the Under 21’s side while we were landed with the usual well-worn jerseys.

At Norton Park the school football team was run by a gym teacher called George Wood. George, a mad keen Rangers fan who was totally dedicated to football, was also a member of the Edinburgh Schools selection committee, and I think it was through him that I was picked for the Edinburgh Schools trials. Somewhat surprised to be selected, I managed to play several games for Edinburgh in the Scottish Schools Cup against the likes of East and Mid Lothian, Falkirk and Glasgow. These games often took place at senior grounds such as Tynecastle and Brockville which was quite a big thing for someone my age. In the Edinburgh side I was selected at outside left because inside left Kenny Watson was a far better player than me. Indeed, because of my shyness and introverted nature, I thought they all were, but it was still a most enjoyable time and a great experience. The Edinburgh side at that time contained several players who would go on to sign professional forms including Watson who would captain both the Edinburgh and Scotland Schools sides before signing for Rangers, George Wood who would later sign for Hearts and Rab Kerr who had trials for Leicester City. The centre forward was another very good player who unfortunately just failed to make it, and at the time of writing Mike Riley is the chairman of the Hibs Supporters’ Club at Sunnyside, who insists to this day that he would often fight my battles for me if I was being bullied by an opponent.

I knew I was a good player and at that time people were starting to talk about me. I was also beginning to come to the attention of people in the game, including some sports writers, although they would still invariably get my name wrong. I was selected for the Scottish Schools trials in a game against Glasgow at Albyn Park in Broxburn, but although I was confident enough during the 90 minutes, looking back I didn’t try nearly hard enough to force myself into the game. This lack of arrogance may well have worked against me and I failed to make it to the final selection. I might be wrong, but I think that Kenny Dalglish may well have played for Glasgow that day, but at inside left they had a boy called Tommy Craig who even then looked a superb player destined for a great future in the game. The only other lad from Edinburgh as far as I recall was a boy called Brian Wilson, a left back who spent time with Chelsea, and would later train alongside me at Hibs in the evenings.

One afternoon after playing for Edinburgh Schools at Stenhousemuir I was approached by a representative from Burnley who asked if I would be interested in going down to the Midlands for a week’s trial. My parents couldn’t see any problems, but although I was keen, I didn’t fancy a week in a strange town on my own and asked if my pal and teammate Kenny Chisholm could come down with me. This didn’t seem to create any problems and Mr Sutherland, the Burnley scout, drove us both down. Unfortunately, it snowed heavily for the entire time we were there making it impossible to play any games, and most of our time was taken up playing against the ground staff in the small Turf Moor gymnasium. On the Friday evening we were taken to see Bradford Schools Under 18’s take on the Scottish Schools, and we also managed to take in Burnley’s home game against Nottingham Forest on the Saturday. At that time Burnley were a very good side with players of the calibre of Ralph Coates, Willie Morgan, goalkeeper Adam Blacklaw, Sammy McIllroy and Alex Elder, but I had eyes for only one. Playing for Nottingham Forest that day was the legendary former Hibs and England centre forward Joe Baker who was in a different class, at times taking on Burnley all on his own. The first player from outside the football league to be capped for the full England side, Baker had moved from Hibs to Italian side Torino in the summer of 1961. An unhappy spell in Italy saw him move to Arsenal before signing for Forest in 1965. During his four seasons at Easter Road Joe had scored 161 times in all games, including a club record of 42 league goals in a single season, and 100 before his 21st birthday. It was a quite remarkable tally, and although it had been six years since his last game for Hibs he was still a hugely revered figure in Edinburgh. That afternoon I just couldn’t take my eyes off of him. He seemed to have it all: pace, aggression and skill; and I never thought for one minute that I would be lining up alongside him for Hibs in the not too distant future.

I was assured that I would be called back to Burnley for trials at a later date, but I never heard from them again. I wasn’t overly concerned however, and was just pleased to be back in Edinburgh clutching the £50 I had been given, which was a quite amazing amount of money for me, or any other 14-year-old at that time, and I went straight down to watch Tam racing at Magdalene wearing a brand new pair of ‘Hipster’ trousers feeling like the ‘Bees Knees’. It was also around this time that I was approached by the Falkirk manager Sammy Kean who had played and coached at Hibs for many years. Newspaper reports at the time claimed somewhat prematurely that: ‘Falkirk have booked the 15-year-old St Bernard’s Under 16’s player Alex Cropley who is reckoned to be one of the brightest young prospects in Edinburgh’. The report went on to say that: ‘Hearts had watched Cropley the previous week against Uphall Saints and had made tentative enquiries only to be informed that the player was destined for Brockville’. Despite the reporters optimism, Kean, or Hearts for that matter, never contacted me again.

A short time later after a Scottish Cup semi-final between St Bernard’s and Glasgow United at Albyn Park in Broxburn, I was approached by the former Scottish International Tommy Docherty, then the manager of Chelsea, who was interested in taking me down to London for trials. My dad however was very much against the idea. I was about to leave school and he thought it best that I had a trade. Docherty suggested that I could attend day release classes, but again my dad put his foot down thinking that I was far too young to go down to London on my own. I was in total agreement as I couldn’t imagine living anywhere away from the comfort and security of home, never mind the bustling metropolis that was London.

One game that sticks in my mind from around that time is a semi-final meeting between St Bernard’s Under 21’s and my former side Royston in the semi-final of the local Evening News Trophy at Old Meadowbank. The game had an unfortunate start when one of the opposing players was stretchered off with a suspected broken leg after a tackle with my brother Tam. The incident put a damper on the rest of the proceedings, but we won the right to play Whitson Star in the final when scoring the only goal of the game near the end.

On the football front it all seemed to be happening for me at this particular time. Not long after arriving back from the ill-fated trip to Burnley I was approached by the Hibs scout Davie Dalziel who had played against my dad as a youngster, who asked if I would like to train with Hibs in the evenings. A few days later Stewart Tulloch who ran the St Bernard’s Under 16’s side took me up to see the Hibs chairman William Harrower at his office in George Street, where I was offered £15 per week wages, probably as much as my dad was taking home at that time. I later found out that most if not all of the other part-timers at Hibs were only on about £5 per week, and I was convinced that either Harrower had made a mistake, or he thought that I was the next great white hope. However, as many chairmen at that time knew very little about the game itself, I thought that the former was more likely, and I decided to keep the secret to myself.

I was now nearly 16 years of age and playing for St Bernard’s on a Saturday and training at Easter Road on a Tuesday and Thursday evening under the watchful eye of Jimmy Stevenson. Stevenson had been brought to Easter Road from Dunfermline in the mid-’60s by the legendary Jock Stein as first team trainer, but after Stein’s premature move to Celtic in 1965 there was no place at Parkhead for Jimmy, and he had remained at Hibs to coach the first team during the day and the youngsters in the evenings.

I left school at 15 to take up an electrical engineering apprenticeship with Dunedin Electrical, in Gorgie of all places, but in truth I hated it. I got on well enough with the boss and the other workers, but sitting at a bench all day winding wire did not appeal to me in the slightest.

By this time I had been poached by Edina Hibs Under 17’s. Although the club had no official affiliation to the Hibernian professional side, Edina were sponsored by the Southern branch of the Hibs Supporters’ Club and it was generally assumed that Hibs would have the first pick of any promising player.

At that time Edina Hibs were a really good side with players like John Brownlie, Willie McEwan and Phil Gordon who were all earmarked for Easter Road. Brownlie and McEwan were already on the Easter Road ground staff and I knew them slightly from training at Easter Road in the evenings. I thoroughly enjoyed playing for Edina and we had some classic games against several very good sides. I remember one game in particular at Leith Links in front of a big crowd when I received a deep cut to my lip after a particularly bad foul. As I was receiving treatment I was surprised to be approached by my dad who whispered in my ear: ‘it was the number seven’. You can guess what is coming next. At the very first opportunity I managed to take my revenge on number seven with a similarly bad tackle. As I was being lectured by the referee, my opponents father came up to me and said: ‘you are a far better player than that son’. It was a lesson learned. It later turned out that it had not been the number seven after all who had fouled me. My last game for Edina Hibs was an East of Scotland Cup final against the simply named Edina at Saughton Enclosure. The easy 4-1 victory was to be my swan song in the amateur ranks, although by receiving money from Hibs at that time, strictly speaking I wasn’t an amateur.

In the summer of 1968, aged only 16, I was called up to Easter Road as a part-time professional. As young as I was, I was fully aware that if I wanted to make my way in the game then the hard work would start here. Luckily, hard work on the football field was something that had never bothered me.

CHAPTER TWO

The Professional Game

THE NEW SEASON couldn’t come quickly enough, and apart from a two week holiday in Lorrett de Marr with a pal, the long summer days were spent struggling with a mixture of emotions that ranged between excited anticipation and nervous apprehension. The only football that I played during this time was in the traditional but disorganised Sunday afternoon games in the local Portobello Park. The games, that could range from 9-a-side to 14 and sometimes 15-a-side, were keenly anticipated by all the participants, even those who played for organised teams on a Saturday. In the winter we would use the goalposts and in the summer when they had been removed to let the grass grow, jackets on the ground would suffice. It was during these Sunday afternoon kick about’s a few years before that I had first started to realise that perhaps I could play a bit. Latecomers would usually have to wait until another player turned up so that both sides would be equal, but in my case I was often told that because I was that much better than most, I would have to wait until another two players could join the opposing side.

For some reason my brother Tam and I always seemed to find ourselves on opposing sides, and rarely a Sunday would pass without us kicking lumps out of each other, real serious stuff, and every week without fail we would have to be separated, sometimes several times, by the other players who all found it highly amusing. Although he was a bit younger than the rest of us, Ralph Callaghan who would later go on to play for Hearts, Newcastle and Hibs, often took part in the games, and he told me later that for this reason alone he used to eagerly look forward to the Sunday games. The strange thing was that at the end of the proceedings Tam and I would walk home together as though nothing had happened earlier. Over the years we had some classic encounters down the park, and I well remember the occasion some time before when a man much older than the rest of us started joining in along with his son. He was a bit of a bully and soon started pushing his weight around. My dad must have heard either Tam or me complaining about it, and one Sunday afternoon completely out of the blue he stunned us by saying that he thought he would come down for a game. You could see immediately that my dad had been a good player, and midway through the game he went in for a crunching block tackle with the older man, then hit him with his shoulder as he turned smashing him to the ground. Everyone was amazed, none more than Tam and me, and that evening we gave him a little more respect than usual. He never came down again, but as far as I can remember, neither did the bully.

At that time Hibs were a reasonable side. They had ended the previous season in third place behind Celtic and Rangers to qualify for the coming seasons UEFA Cup, but behind the scenes many of the players were unsettled. Although the club would reach the League Cup final that season they would end the campaign in 12th place, their lowest position for several years. During the summer their Danish centre half John Madsen had walked out of the club to return home. Still under contract he had effectively banned himself from the game at any level. The former Rangers Scottish international Alex Scott, who had been signed the previous season from Everton, was also unhappy at losing his first team place to the rising star Peter Marinello, and Peter Cormack, perhaps Hibs’ best player at that time, was desperate for a move to England after watching a succession of his teammates making the journey south in recent years. While the dressing room couldn’t exactly be described as unhappy, there was certainly a degree of unrest.