20,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

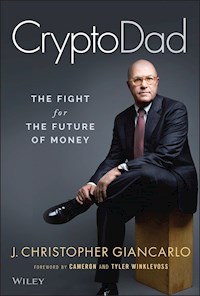

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

An insider's account of the rise of digital money and cryptocurrencies

Dubbed "CryptoDad" for his impassioned plea to Congress to acknowledge and respect cryptocurrencies as the inevitable product of a fast-growing technological wave and a free marketplace, Chris Giancarlo is considered one of "the most influential individuals in financial regulation." CryptoDad: The Fight for the Future of Money describes Giancarlo’s own reckoning with the future of the global economy—at the intersection of markets, technology, and public policy—and lays out the fight for a Digital Dollar.

CryptoDad is Giancarlo's own personal story, detailing his forays into the world of Wall Street to his tenure as the 13th Chairman of the United States Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), where he pushed for the agency to recognize the digitization of markets. His growing fame as a Twitter presence in this essential debate has given Giancarlo a platform to makes a case for the future of cryptocurrencies as the natural successor to America’s current failing financial market infrastructure.

CryptoDad provides readers with:

- A thorough exploration of digital change and how it affects the lives of everyone in a global economy

- A revolutionary consideration of regulatory responses to the rapid pace of technological innovation

- A call to update our aging financial organizations, particularly the infrastructure of money itself, and focus on renewed faith and confidence in free market innovation

- A foreword by Cameron and Tyler Winklevoss, two of the biggest names in cryptocurrencies

CryptoDad argues that the next digital wave will be the coming Internet of Value, where cryptocurrencies will do the Internet of Information did to immaterial things: make them accessible, distributable, and movable instantly across the globe. This book is an ideal introduction to the importance of technology in the marketplace.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 658

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Foreword

Preface

Introduction

Antiquated Infrastructure

Internet of Value

The Digital Future of Money

Notes

PART I: OPENING LAPS

Chapter 1: Down in the Swaps

Red Light

Swaps Breakdown

A Good Long Walk

Lemons into Lemonade

Meeting in a Tower

Notes

Chapter 2: Starting Grid

Moving on Up

Groovin'

Dot‐Com

Who, Me?

Notes

Chapter 3: Heading Down the Highway

The Layout

White Paper

Action by No Action

Position Limits

Notes

Chapter 4: Scanning the Horizon

Nighttime Driving

Driving Through the Rearview Mirror

Peering over the Dashboard

Blockchain Briefing

First, Do No Harm

Round Up the Usual Suspects

Feel the Road

Improving Signal to Noise Ratio

Notes

Chapter 5: Meeting the Locals

Summer Breeze

Politics or Policy

Your Money or Your Life

Making Introductions

Finger Food

Notes

PART II: READING THE DASHBOARD

Chapter 6: Taking Hold of the Wheel

Consequences

Taking Charge

Priority: Leaders

Building the Brand

Picking Captains

Street Smarts

Teamwork

Taste Test

Battle Ready

Fostering Innovation

Unanimous Confirmation

Seal of Office

Sign of Peace

Notes

Chapter 7: Bitcoin Approaches the Beltway

Bits and Bytes

Bitcoin Mining

From Silk Road to Main Street

Into the Fray

Bitcoin Rally 1.0

Preparing for Launch

Foreign Correspondence

Task Force Crypto

Notes

Chapter 8: Go Time

Taking Action

Covering Bases

Physical Delivery

Checking In

Counting Down

Good to Go

Band on the Run

Friendly Fire

Sounding the “All Clear”

Before the Council

Clear Mountain Air

Notes

PART III: SLIPSTREAM

Chapter 9: Facing Resistance

Battling Narratives

S.P.E.C.T.R.E.

Drinks for Two

Seeing Red

Clear as a Bell

Setting Things Straight

Notes

Chapter 10: “CryptoDad”

Kopper Kettle

“We Owe It to This Generation”

Notes

Chapter 11: The Oval Office

Come on Down

Mission Accomplished

Notes

Chapter 12: The Road Goes On

What Next?

Up in the Ether

Grand Tour

F.U.D.

Peaceful Waters

New Measurements

Building a Math House

Here to Stay

Breaking Records

Notes

PART IV: FINISH LINE

Chapter 13: Last Laps

Domestic Affairs

Hand on the Wheel

Back to Our Roots

Missing the Mark

International Affairs

Bridge over Brexit

Ministry of Silly Walks

Notes

Chapter 14: Checkered Flag

Turning in My Chips

Meet the New Boss

Boca

Taking Leave

Notes

Chapter 15: The Winding Crypto Road

Beside Still Waters

The Nature of Money

The Crypto Revolution

Stablecoins

DeFi

Peer‐to‐Peer Oversight

Crypto Native Regulation

Bitcoin Rally 2.0

Miami Vice

Inexorable Motion

Notes

Chapter 16: Digital Dollars

Fight for the Future of Money

A Digital Dollar

Drivers of Interest

Olympic Gold

Cutting Edge of Money

Competing CBDC Networks

All Together Now

Expectation of Digital Privacy

Safety in Numbers

Back on the Mound

Notes

Conclusion: Roadside Thoughts

Philosophy of Value

Freedom and Responsibility

Spirit of Democratic Regulation

Free Markets and Free Peoples

A Future of Human Potential

Notes

Postscript

Appendix: Remarks of CFTC Chairman

Introduction

Challenges and Opportunities of Virtual Currencies

Federal Oversight of Virtual Currencies

Virtual Currency Products: A Review and Compliance Checklist

Next Steps

The Choice

Conclusion

Notes

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Index

Historical Bitcoin Prices

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Foreword

Preface

Introduction

Begin Reading

Conclusion: Roadside Thoughts

Postscript

Appendix: Remarks of CFTC Chairman

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Index

Historical Bitcoin Prices

End User License Agreement

Pages

iii

iv

v

ix

x

xi

xii

xiii

xiv

xv

xvii

xviii

xix

xx

xxi

xxii

xxiii

xxiv

1

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

83

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

159

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

227

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

294

295

296

297

298

299

300

301

302

303

304

305

306

307

308

309

310

311

312

313

314

315

316

317

318

319

321

323

324

325

326

327

328

329

330

331

332

333

334

359

360

361

362

363

364

365

366

367

368

369

370

371

372

373

374

375

376

377

378

379

380

381

382

383

384

385

386

387

388

389

390

391

392

393

394

395

CRYPTODAD

The Fight for the Future of Money

J. Christopher Giancarlo

Copyright © 2022 by J. Christopher Giancarlo. All rights reserved.

Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey.Published simultaneously in Canada.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 750-4470, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permission.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor author shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

For general information on our other products and services or for technical support, please contact our Customer Care Department within the United States at (800) 762-2974, outside the United States at (317) 572-3993 or fax (317) 572-4002.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic formats. For more information about Wiley products, visit our web site at www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Giancarlo, J. Christopher (James Christopher), 1959- author.

Title: CryptoDad : the fight for the future of money / J. Christopher Giancarlo.

Description: Hoboken, New Jersey : Wiley, [2022] | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021036636 (print) | LCCN 2021036637 (ebook) | ISBN 9781119855088 (hardback) | ISBN 9781119855101 (adobe pdf) | ISBN 9781119855095 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Cryptocurrencies. | Digital currency. | Finance—United States.

Classification: LCC HG1710 .G53 2022 (print) | LCC HG1710 (ebook) | DDC 332.4—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021036636

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021036637

Cover Image: Mike McGregor Inc.Cover Design: Paul McCarthy

This book is dedicated to three wise teachers:

Ella Jane, my mother, who taught faithfulness in living;

Henry, my professor, who believed liberty is the goal of learning; and

Regina, my wife, who shows kindness as the essence of love.

Foreword

Cryptocurrency, or “crypto” as it is colloquially known, is a pretty big deal. In our opinion, a bigger one than the Internet itself. And we believe it has the potential to have as great an impact on personal freedom as the printing press, the personal computer, and the early, open Internet. Why? Because crypto makes decentralization possible, which is to say its center of gravity is you, the individual.

Prior to the invention of Bitcoin, the idea of a decentralized network, in which unrelated computers around the world could reliably reach agreement with each other on something (e.g. who owns what), was thought to be entirely theoretical. The challenge lies in the possibility that one or more computers in the network could be bad actors trying to confuse the others.

In computer science, this agreement problem is known as The Byzantine Generals' Problem. When Satoshi Nakamoto, Bitcoin's pseudonymous creator, published the Bitcoin white paper in 2009, she, he, or they presented the world's first ever solution to this hitherto intractable problem. As described, the Bitcoin mining algorithm ensures that a network of computers that don't know each other will in fact reach agreement with each other in a reliable manner. And that this agreement or consensus—what today, we call a blockchain—would be immutable and verifiable.

Historically, such agreement had to be entrusted to a central party or ended up concentrating toward one. Money has long been the purview of governments and finance the domain of big banks. Tim Berners-Lee's original, utopic vision for the commercial Internet—an open network of interconnected computers—has become a closed, dystopic oligopoly of data cartels. When you log on to the Internet today, you're really logging on to one of five companies: Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix, or Google, aka the FAANG companies. Has there ever been a more appropriate acronym?

The problem with centralization of power was captured best by Lord Bryon: “Power corrupts; absolute power corrupts absolutely.” These sectors are centralized, not because it is the best approach, but because it has been the only approach … until now. Satoshi's breakthrough not only made the decentralization of money possible, but it also provided a blueprint for the decentralization of anything.

We now can envision a future where the Internet, finance, and money will not be controlled by a few, but by the many. Where the value of these social networks (they are all social networks) will not accrue to just a handful of CEOs and companies, but to all of us, their users. Where you no longer need someone's permission to invest, borrow, or build. A level playing field with no inside baseball.

Bitcoin was the first cryptocurrency as we have come to know them. It has created an entirely new economic sector we now call crypto. This sector, like the Internet, has grown from total obscurity into one that can't be ignored. While today, it still appears to most as a niche technology, tomorrow it will be everything. When Jeff Bezos was first pitching Amazon to potential investors, the first question he was always asked was, “What's the Internet?” Crypto's story arc will be no different.

Crypto is not just a technology; it is a movement. One that offers the possibility of greater choice, independence, and opportunity for all. It can achieve things that our current systems can't even begin to contemplate. It allows our money to work like email. Its barriers to entry are low—requiring only an Internet connection and a smartphone. It has the power to redesign the Internet, the financial system, and money in a way that fosters and protects the rights and dignity of the individual. These are quite awesome possibilities and embody the ethos and founding principles of our country. Crypto is very American.

It would have been hard to predict the sheer economic opportunity of the Internet back in the early 1990s. Not long ago, many of the Internet companies that today are the biggest economic drivers of the global economy were seen as novelties or didn't even exist. The majority of these companies are American and their economic growth and prosperity was captured primarily by Americans. America won the Internet.

This was not a coincidence or the result of a lucky accident. This can be traced entirely back to the pro-entrepreneurial culture that America has long established through its rule of law and thoughtful regulation. These choices that we made gave rise to sophisticated capital and credit markets that provided nourishment to start-ups and solidified America as both the cradle and hotbed of innovation. Entrepreneurs came to America to build because they could do so with a clarity and pace that was impossible to match in any other country in the world. And once this ecosystem was established, it became both self-reinforcing and self-perpetuating.

But while the race for the Internet is more than three decades underway and America's leadership position is firmly entrenched, another one has begun—the race for the Internet of Money. It's still early, but unlike the race for the Internet, the United States is not the leader. To date, the biggest crypto companies are being built offshore. In many cases, they are being built by US citizens who have left America because the regulatory environment is too slow, opaque, or draconian to keep up with the global pace of innovation. And for perhaps the first time ever, US customers are flocking to offshore financial platforms because they simply can't get what they want here, at home.

This sad irony is painful to admit. America is not where the majority of crypto entrepreneurs go to build. The land of the free and the home of the brave, the bastion of democracy and free markets, now, all of a sudden, has an uncertain future as the host country for the greatest technology revolution of the last quarter century. America has been operating under the false pretense that a global, decentralized, permissionless technology movement that transcends borders is going to wait around for America's permission. It won't. America has gotten complacent. It has confused the Internet boom with the crypto boom, assuming that because we won one, we will win the other. Our past success will not be an indicator or causation of our future success.

But alas, all is not lost. It is still early, and our fate rests entirely in our own hands. Our country has leaders like Chris Giancarlo who understand the vast promise of cryptocurrencies. Under his tenure as chairman of the Commodities Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), Giancarlo championed crypto throughout the halls of government and left behind a pro-crypto legacy at the CFTC that lives on to this day. His dedication to our country becoming a leader in crypto, as we have been in the Internet, earned him the nickname “CryptoDad” on Twitter and legions of Internet followers. And his sense of duty and patriotism that led him to serve in our government for five years similarly motivates him to make sure America is not left behind. Giancarlo is a true American.

Our sincere hope is that many will read this book and begin to better understand not only the enormity of the opportunity that stands before us, but also that our ability to prosper from it is not guaranteed. Our hope is that this book will give you an insider's view into where we are as a country with respect to our regulatory approach to crypto and where we need to be. Armed with this knowledge, we can then start working together toward a solution. We can build an ecosystem with the proper ingredients and nutrients that will allow crypto to flourish here, on our shores. Together, we can ensure that America becomes the undisputed best place for entrepreneurs to build in crypto. That America remains the land of opportunity where you go to make your dreams come to life.

We hope you will join us and CryptoDad as we fight for this future. We won the space race, we won the Internet. Now, let's go win the fight for the future of money.

Onward and upward,Cameron & Tyler WinklevossJuly 16, 2021

Preface

July 14, 2021

En route to Big Moose Lake, New York

I wrote this book to tell a story. A story of a five-year journey around the globe through the centers of financial power. A true story from my eyes and ears. Of what I saw and what I experienced, what was said and who said it. Much of it is serious, some of it funny, a bit of it is revealing about the way decisions are made at the highest levels that affect the lives of each one of us.

It is a story of real events that took place during the later portion of the twenty-teens: 2014–2019. It is a story of real people, many of whom are wonderful, some are dear to me, a few disingenuous, most of them important in more or less obvious ways to how the US and global economy are run.

I am telling this story to interest readers who may wonder what it is like to be in the setting of political power over financial affairs in Washington and, occasionally in London, Brussels, Basel, and Hong Kong.

I trust readers will enjoy the ride. I hope so, because along the way I have a more important message to impart. The message is that something big is going on all around us. Something bigger than one person's accidental and quixotic experience through the halls of power. It is a change that comes not once in a generation, but perhaps once every few centuries.

This change is being driven by a new wave of the Internet—the Internet of Value—that permits the instant transfer of things of value over the worldwide Web directly from person to person without the need for intermediaries.

The revolutionary change that I am talking about is in the way society experiences holding and sharing things of value, including the most valuable thing of all: money. Soon, moving money will be as simple, immediate, and cost-free as sending a text message, whether across a supermarket counter or around the globe.

Why is this revolutionary? Because up to now money has been limited in space and time. The ability to move money far from home is somewhat slow and costly and limited to banking hours by those who can afford it. Now, for the first time in human history, the use of money will transcend space, time and, importantly, social class.

Here is the deeper story that I will tell: how money is changing right before our eyes. And, that you, the reader, must take hold of that change. You and your fellow citizens must speak up and effect that change.

Money is as much a social construct as it is a government one. Together, we must make sure that the values that are enshrined today in the US dollar and the currencies of other democracies—values like individual liberty, freedom of speech, personal privacy, free enterprise, and the rule of law—are encoded in the digital money of the future.

Money is too important to be left to central bankers. You and I must assert a voice in the rapidly coming change in money. We must make sure that our financial privacy and economic liberty are safe and secure. If we do not, the people I tell you about in this book will make those decisions for us. We can't let the promise of the convenience of digital money blind us to the threat of the loss of our liberty to unelected technocratic and government elites, however noble their intentions.

Without inviolable protections for such civil liberties as freedom of speech, free enterprise, and individual economic privacy, digital Dollars, digital Euros, or other forms of digital currency would be no more worthy of a democratic people than the currency of authoritarian ones. Free societies have everything to gain by encoding into sovereign and non-sovereign digital currency stout protections for individual liberty and privacy. Free people have everything to lose by neglecting it. The choice is essential to the future of civil society.

This book is not a technical book about the complexities of Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies or their underlying distributed ledgers, although it does try to explain those things in simple terms. It is not a guide to Bitcoin trading strategies. This book will not tell you whether crypto is a good or bad investment. It is not even an appeal for the creation of a digital dollar, although it does explain what is at stake in doing so. No, this book is more basic than that.

This book is written to take a stand for the future of economic privacy and financial liberty. We must harness this unstoppable wave of digital money—the Internet of Value—to advance greater economic inclusion, financial and economic freedom, and human aspiration for generations to come. We must be bold, not timid. Ultimately, we must insure that the future of money is determined by a free society of fearless people, philosophers and farmers, teachers and musicians, fast-food cashiers and hotel cleaners, doctors and dreamers, and accidental regulators like me.

And people like you.

Introduction

“Dreams I had just yesterday

Seem to all have passed away in time

And, once again, I have a memory

Another treasure in this life of mine,

This life of mine.

“Fate shows no mercy to love

And so, I pack my wheels once more

‘cause there's so many

Backroads in life yet to explore

Yet to explore

“I know I can't ever change

My lone person or my mind

And so, I have to be on my way

And leave those realities behind

Yeah, leave 'em behind

“And now, the sun is shining down

Upon a road

Twisting and unwinding

For this, I gave my all

I gave my all.

“I'm lookin' for a road

I'm lookin' for a road

I'm lookin' for a road

Again.”1

Thank you for opening the pages to this book. I'll tell you why I wrote it.

The future of the US economy—and, indeed, the world's—will be determined at the dynamic intersection of markets, technology, and politics. The interplay of these determines the cost and availability of the food we eat, the energy that heats our homes, the electricity that powers our smartphones, our mortgages and auto loans, and, ultimately, the money we use to pay for all of these. It determines the continued affordability of the vaunted “American way of life.”

I have spent a 37-year career in that economic intersection, first as a Wall Street lawyer and later as a finance executive. I then served for 5 years at its center at one of the world's least understood yet most important market regulators, the US Commodity Futures Trading Commission, known as the CFTC. It was there that, quite unexpectedly, I glimpsed the most profound change in generations: The rise of the Internet of Value, Bitcoin, and cryptocurrencies.

So this book is, in part, a personal one about how I have navigated my professional path in a radically changing world. But I hope it is much more than that. It is also a call to arms. Based on what I have seen, I believe democratic society faces an urgent need to courageously confront the extraordinary transformations wrought by the Internet of Value that will intimately affect the daily lives of each and every one of us. They must be shaped by a free people.

Here's why I say that. Let me begin with three key observations about financial markets.

Antiquated Infrastructure

First, consider that America's physical infrastructure—its bridges, tunnels, airports, and mass transit systems—that were cutting edge in the last century but have been allowed to age and deteriorate in the current one.

Sadly, the same is true about much of our financial infrastructure, both in the United States and in many developed Western economies. Systems for check payment and settlement; shareholder and proxy voting; investor access and disclosure; and financial system regulatory oversight—once state-of-the-art and global models in the twentieth century—have fallen behind the times in the twenty-first century. In some cases, embarrassingly so.

This aging financial system puts developed economies like the United States at a competitive disadvantage to the likes of China that are building new financial infrastructure from scratch with twenty-first century digital technology. Here's a good example: it typically takes days in the United States to settle and clear retail bank transfers. In many other countries it takes mere minutes, if not seconds. It also takes days to settle securities transactions and weeks to obtain land title insurance. It is still often faster to move money around the globe by stuffing cash in a suitcase and carrying it on a plane than it is to send a wire transfer.

Nothing better reveals the limits of our existing financial system than the US government's initial financial response to the COVID-19 pandemic in the spring of 2020. Tens of millions of Americans had to wait a month or more to receive relief payments by paper check. More than a million payments were made to people who were dead.

Internet of Value

A second observation is that these aging financial and regulatory systems are struggling to adapt to the next wave of digitization that I and some others call the “Internet of Value.”2

The first wave was the Internet of Information. Wikipedia is an example and emblem of that first wave: a massive decentralized, online reference authority composed collaboratively by volunteers. That initial wave took information written, owned, and controlled by elite publishers like Encyclopedia Britannica and democratized it, rendering it easily accessible at a keystroke, anytime, anywhere, and for free.

That first Internet wave was superseded by another: the “Internet of Things.” Thanks to this wave, seemingly every place we shop and dwell, everything we wear and drive, and every device we engage with is connected to the Internet.

We are now on the cusp of the Internet's next wave: the Internet of Value.

As remarkable as were the earlier waves, the Internet of Value will be an even deeper transformation of our economic selves than the earlier waves combined. This wave will do to currency, financial instruments, and economic activity what the Internet of Information did to knowledge: reduce costs, increase speed, transcend barriers, improve accessibility, enhance certainty, and decrease bottlenecks to instantaneous transactions across the globe.

In this wave, things of value—such as contracts for energy, agricultural, and mineral commodities; stock certificates, land records, and property titles; cultural assets like music and art; and personal assets like birth records and drivers licenses—will be stored, managed, transacted, and moved about in a secure, private way from person to person, without third-party intermediaries. This next wave of the Internet will shift the medium of trust from large centrally managed institutions to person-to-person digital handshakes powered and secured by cryptography, tokenization, and shared ledgers carried across a network of personal computers and smartphones. Think of the ability to send money or confer ownership over property by mere text message without having to go through an intermediary—a powerful bank or a credit card company—to authenticate who you are and the person you are sending it to. The opportunities will be no less transformative than what Uber did to mobility, Airbnb did to lodging, and Amazon did to commerce. We are only in the middle innings of what will be a decades-long digital revolution.

Ask yourself: When was the last time you mailed a stamped letter rather than sent an email? When was the last time you pasted photos into an album instead of stored them on your mobile phone? When was the last time you played a CD, cassette tape, or vinyl LP rather than listened to Pandora or Spotify? If the Internet could transform letter writing, photography, and music in one generation, it is naïve to think the Internet will not do the same to financial services and money. In a few years' time, writing a paper check will be as archaic as sending film to Kodak to be developed. So will sending money by wire transfer—or even via mobile apps like Venmo or Square Cash—since all these ostensibly “digital” methods still rely on costly intermediaries, such as banks and credit-card companies. Just over the horizon is a world in which we will soon send things of value directly to the recipient, mobile device to mobile device, without any third-party needing to assist—or take a cut.

Nowhere will the Internet have a more dramatic impact than in the realm of money. Sir Jon Cunliffe, the widely respected deputy governor of the Bank of England, once commented to me that, every several generations, society re-asks the question: “What is money?” He thinks this latest Internet wave is prompting society to ask that question once again.

He's right. Society has been questioning the nature of money for over a decade now. Bitcoin3—rising from the ashes of the last financial crisis in 2008—was the first digital asset. Since its advent, the private sector has launched thousands of budding, non-sovereign cryptocurrencies of lesser or greater promise.

Clearly, the private sector is way ahead of governments and central banks in exploring digital money. But lately, governments are starting to react. Most of the world's central banks are now taking a serious look at a sovereign form of cryptocurrency, called central bank digital currency.

The world as we know it today is one of competing currency zones in which monetary systems, banking, and foreign accounts are generally oriented to one reserve currency or another. Think of the US dollar zone and the “Eurozone.” As I will explain in this book, those old currency zones may well be replaced tomorrow by widely networked and integrated national digital currency zones. There likely will be a Chinese digital currency zone and perhaps a Digital Euro zone. In these zones, central bank digital currencies will be networked through distributed ledgers with all important financial functions and transactions—including retail credit and business lending, domestic and global payments, securities and commodities trading, and central bank monetary policy—under the control and watchful eye and sway of powerful central banks. The increase in speed, efficiency, and velocity of money could turbocharge economic growth. Such centralized economic and financial control for major world economies would be unprecedented. It would be the utmost expression of the Internet of Value: fully-integrated, networked, digital economies.

The Digital Future of Money

My third observation is that the standards, protocols, and rules for the digital future of money are being established today. If we act now, we can make sure that democratic values—freedom of speech, individual economic privacy, free enterprise, and free capital markets—are encoded in the digital future of money. In so doing, we can harness this wave of innovation to maximize financial inclusion, capital and operational efficiency, and economic growth for generations to come.

If we do not act wisely and quickly, however, this new Internet wave will lay bare the shortcomings of America's aging, analog financial systems. Worse, it will mean that the values of our nondemocratic economic competitors—state surveillance, social credit systems, law subservient to the state, and centrally planned economic activity—will be embedded into the future of money, diminishing the vibrancy and health of the global economy, individual liberty, and human advancement.

This book is about the digital transformation of money and how it will change the lives of everyone in the global economy. But it is also a more personal story. It's about how I, a Margaret Thatcher–admiring, free market Republican, helped build one of the world's leading derivatives trading platforms only to find myself in the epicenter of the 2008 financial crisis. That experience led me to support the financial market reforms in the Dodd–Frank Act—a law that I now view as the last major “patch” of the long-standing analog, account-based financial system.

Those experiences led to my appointment to the CFTC by President Barack Obama. They also led to my subsequent elevation to CFTC chairman by President Donald Trump—after confirmation by a unanimous Senate.

Like Jimmy Stewart in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington,4 I went to Washington as a political naïf with reformist goals. My immediate objective was to complete and improve reforms to the swaps market. Yet, halfway through, I found myself staring at the first ripples of the next wave of the Internet—a wave that will soon shake the existing financial system to its core.

The immediate challenge was a product called Bitcoin futures, which I will discuss in more detail later. I faced significant pressure to hamper its debut. But I resisted that pressure—not without a few moments of self-doubt. Instead, I led the agency to encourage financial innovation, prepare for the Internet of Value, and oversee the development of crypto derivatives. Braving political risk, we reduced regulatory uncertainty for financial market innovators. The decision laid the groundwork for the emergence of an enormous new ecosystem of retail and institutional cryptocurrency greater than anything I could have anticipated. For that, the online cryptocurrency community dubbed me “CryptoDad.” This book is my story.

***

Undoubtedly, the continuing evolution of the Internet of Value will come in fits and starts. There will be bubbles, crashes, mistakes, and successes. There will be fiascos and criminal behavior as with any profound change. There will be enormous business disruption and even more business innovation that still cannot even be imagined.

Yet, the technology will not be stopped. Suppression in any one jurisdiction will just move the evolution to another. The direction of travel for this innovation is increasingly clear and, frankly, amazing. Bitcoin is just the tip of the iceberg. The question for American policy makers is whether they have the courage to let this new wave of innovation take place here in an intelligently regulated fashion that contributes to our economic benefit or irresolution to force it to happen elsewhere.

The question for a free people is whether they will make their voices heard in the design and operation of the digital future of money. Will the reasonable expectation of privacy from both commercial and governmental surveillance provided by paper money be found in digital money? Will a digital dollar or non-sovereign forms of digital money secure individual economic privacy against government surveillance guaranteed by the US Constitution and expected by the American people? Who will decide?

I am convinced—and I hope to persuade you in this book—that the ongoing evolution of the Internet will revolutionize money and banking in the same way it has revolutionized communications, photography, retail shopping, business meetings, and entertainment. It is naive to think that it will not. Yet, the venerable global financial services industry and its central bank overseers have been slow to even acknowledge its arrival. Some have a vested interest in the old infrastructure. The western economies will not keep pace if the matter is left to politically browbeaten bank executives, political protectors of the status quo, a few snarky financial journalists, and rigid central bankers. We need officials with courage, determination, foresight, and the willingness to take risk.

If we fall behind the curve, then the future rules, protocols, and values of digital money will be set by our nondemocratic economic competitors. Instead, a free society must show the courage of its bedrock convictions. We must fearlessly lead the digital revolution in money and finance and not cede leadership in the Internet of Value to autocratic economic competitors. That's the only way we can counter the values of authoritarianism with democratic values: individual economic privacy, rule of law, and markets free of state control.

That battle is being waged today. It will take daring and determination to regain the initiative. This book is about summoning that courage—both socially and governmentally—to overcome political inertia, institutional complacency, and societal fearfulness in the fight for the future of money.

Notes

1

. Chris Giancarlo & Ken Hasimoto, “Looking for a Road,” unpublished song lyrics, 1975.

2

. For thoughtful discussions of the Internet of Value, see: Tapscott, Don, Tapscott Alex, “Blockchain Revolution: How the Technology Behind Bitcoin and Other Cryptocurrencies is Changing the World,” Portfolio Penguin (January 1, 2018) and Casey, Michael J and Vigna Paul, “The Truth Machine: The Blockchain and the Future of Everything,” St. Martin’s Press (February 27, 2018).

3

. Conventionally, the word “Bitcoin” is often capitalized when referring to the cryptocurrency as a concept, but lower-cased when referring to its individual tokens, or units of value. Since I will discuss Bitcoin as a concept, I will always use the upper case form in this book.

4

. Mr. Smith Goes to Washington is a 1939 political comedy-drama film directed by Frank Capra starring Jean Arthur and James Stewart about a newly-appointed and naive US Senator who fights to reform a tainted political system.

PART IOPENING LAPS

Chapter 1Down in the Swaps

If everything seems under control, you're just not going fast enough.

—Mario Andretti (champion auto racer), Interview with Sam Smith

Red Light

Thursday, November 6, 2014 (CFTC Headquarters, Washington, DC)

“You cannot speak at SEFCON V.”

I looked at my senior legal counsel, Marcia Blase, for a moment and let that sink in.

“What? I thought that we were good to go? What happened?”

SEFCON, which had launched in 2009, was the annual Swap Execution Facility Conference. To many readers that must certainly sound like some obscure Wall Street gathering—and a boring one at that. But it was then the premier industry event focused on the important and growing category of trading platforms—swaps execution facilities—that were defined and mandated by Title VII of the Dodd–Frank Act. Dodd–Frank was the landmark financial industry reform legislation passed in the wake of the 2008 crash.1 (More about this swaps business momentarily.)

This conference was organized by a trade association I had helped form a few years before: the Wholesale Markets Brokers Association Americas (WMBAA). I was a past-chairman of WMBAA, stepping down in 2013 when the Obama Administration approached me about serving on the CFTC. Now, as a CFTC commissioner, I had tentatively accepted an invitation to return to SEFCON to address the audience from my new perspective as a regulator.

“The White House will not grant you a waiver. They consider it non-essential. You can't speak at the conference.”

Swaps Breakdown

Before I continue the story of SEFCON and the Obama White House, let's step back to answer a preliminary question: What are derivatives and swaps?

Though unfamiliar and forbidding terms to some, derivatives and swaps are nothing less than the foundations of a stable and secure financial system. And, as I will explain later in this book, the advent of derivatives on cryptocurrencies has paved the way for a dramatic expansion and maturation of crypto as an entirely new investment asset class and subject of innovative financial services.

Derivatives are tools that transfer risk among willing participants. They allow an individual or institution with risk they don't like or cannot bear to transfer that risk to someone who's capable of bearing it in return for some payment. We use this idea all the time in our daily lives. We constantly “hedge our bets” by offsetting our risk. For example, we might stretch to buy a condo near the seashore, but hedge our investment by renting it out to people all summer long to get some money back. We lower the risk of our investment in the condo by sharing it with others.

History of Derivatives

Investors, farmers, and manufacturers have used derivatives for thousands of years to manage commercial and market risk. The classical philosopher Aristotle describes the Greek mathematician Thales making money off options contracts on olive presses as early as the sixth century BCE.2 Derivatives allow users to guard against gains or declines in the value of underlying physical or financial assets, such as agricultural commodities, interest rates, stocks, bonds, trading indices, or currencies. They do this without requiring the user to buy or sell the underlying assets. In this sense, derivatives are a form of insurance, but one that does not require the insured to incur a loss in order to recover.

American derivatives markets go back at least to the nineteenth century. The first were agricultural commodity futures markets in cities like New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, St. Louis, New Orleans, and Kansas City. These markets allowed farmers, ranchers, and producers to hedge production costs and delivery prices. That, in turn, helped ensure that American consumers could always find plenty of food on grocery store shelves.

Derivatives markets are one reason why American consumers today enjoy stable prices in all manner of consumer finance, from auto loans to home mortgages. Derivatives markets influence the price and availability of the energy used to heat homes and run factories. They also help set the interest rates borrowers pay on home mortgages and the returns workers earn on their retirement savings. Airlines use derivatives, too. The reason carriers are willing to quote us a fare for a ticket on a flight six months from now is that they are hedging their future fuel costs. The same is true for oil producers and refiners.

Agriculture Futures

Say I am a farmer and I own 444 productive acres—the national average for a family farm. Assume further that I rotate between soybeans and corn, which is common. To keep my farm in business and my bills paid, I need to know a lot. I know my soil and the effects of various weather patterns on my crops. I know what my farmhands cost and what my gasoline costs. I know what my seed costs. I know what my fertilizer costs. What I don't know, though, is what the price is going to be for soybeans come November. So, I add up all the costs for the year—the farmhands, the tractor, the gasoline—and that comes to $6.75 a bushel. But when I go to market, I know from experience that soybean prices could range anywhere from $6.00 to $9.50 per bushel. Those varying prices could spell the difference between windfall profits and bankruptcy.

So how do I transfer that risk to somebody who is willing to bear it? Well, what I can do is enter into a contract on the futures market. I lock in $7.75 a bushel for at least half my production. That way I know that if there is too much supply and bushels are selling at less than my $6.75 cost, I'm going to make at least a dollar more and keep my farm solvent. Of course, I'm giving away some of my upside if the price goes up to $9.50 a bushel. But at least I'll make those profits on the other half of my production. I'm trading risk for certainty.

Global trade also depends on derivatives. Without markets to hedge the risk of fluctuating currency exchange rates, manufacturers and growers would be afraid to accept any currency for their exports other than their own. Without markets to hedge the risk of differing interest rates around the globe, banks and borrowers would be reluctant to transact cross-border loans. Without derivatives, goods, services, and capital would not freely flow across national frontiers. In short, there would be no global marketplace.

Fortunately for the world economy, a handful of true visionaries in Chicago—such as Leo Malamed3 and Richard Sandor4—invented financial futures, swaps, and other derivatives. Fortunately for the United States, these products—so essential to global commerce—are priced in US dollars and remain largely traded in New York and Chicago to this day.

While often derided in the tabloid press as “risky,” derivatives—when used properly—are economically and socially beneficial. More than 90% of Fortune 500 companies use derivatives to manage global risks of varying production costs, such as the price of raw materials, energy, foreign currency, and interest rates.5 In this way, derivatives serve the needs of society to help moderate price and supply to free up capital for economic growth, job creation, and prosperity. It has been estimated that the use of commercial derivatives added 1.1% to the size of the US economy between 2003 and 2012.6

Derivatives make it easier for Americans and American businesses to participate in the growth of our economy. As battered and bedeviled as the American Dream may be these days, it would truly be a myth without swaps. The reason the standard American homeownership tool is a 30-year fixed rate mortgage is because of derivatives. If you think about it, interest rates are not staying flat for 30 years. Interest rates bounce all over the place. But banks are entering into swaps contracts in order to reduce their interest rate risk so they can offer you that fixed rate. Same deal with five-year loans for auto purchases. In Western developed economies, so much of the price and supply stability that we consumers enjoy is provided by these derivative markets.

When you step into your supermarket, do you ever stop and ask: Oh gosh, was it a good harvest this year? Will I have to pick over a few rotten tomatoes? Will there be any bread on the shelves? You do not. You just wander the aisles filling your shopping cart with an abundance of fresh fruit, vegetables, and produce year in and year out. Well, thank derivatives for that.7

In many nations around the world, people do experience those concerns. When there are bad harvests and undeveloped and insecure trading markets, not only are the shelves bare—but there may be no food next year because the farmers will have gone bankrupt.

Food for the Future

As of 2014,8 about 800 million people around the world today were undernourished. That's roughly one in nine of the world's 7.2 billion people—a staggering shortfall. Now consider that there will likely be another two billion people on earth in 30 years.9 Even if those projections are only half accurate, we will have another one billion people on earth by 2048. How will all of these people be fed?

Clearly, the world's agricultural exporting nations, including the United States, will play a big part in feeding the globe in the decades to come. These food exporters can feed an additional billion people because of the critical support of well-functioning financial and derivatives markets. Efficient and well-regulated derivatives markets serve at least two critical roles in helping to feed the world's growing population. First, they allow markets to resolve imbalances dispassionately and efficiently by providing reliable and fair benchmarks for prices. Second, they reduce price volatility in a resource-constrained world by removing the economic incentive to hoard physical supplies. They allow farmers to quantify and transfer risks they want to avoid at a reasonable price to persons willing and able to hold that risk. They help control costs and facilitate return on capital to support essential investment in farming equipment and agricultural technology necessary to meet increased global food demand. Providing farmers this risk protection reduces earnings volatility and thus price volatility, benefiting everyone, including millions of consumers who have never heard of derivatives markets.

The greatest beneficiaries of global derivatives may well be the world's hungriest and most vulnerable. If derivatives trading were ever to suddenly cease, they would certainly suffer the most from the extreme price volatility in basic food and energy commodities that would result.10 In developed economies like the United States, we rarely have to worry about such things thanks to two main types of derivatives. The first type are traded on organized exchanges, like the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, and are called futures or options. The second type are traded in a more negotiated process called “over the counter.” Many of the latter trades are referred to as “swaps,” because two parties agree to exchange cash flows and other financial instruments at specified payment dates during the life of the contract.

I have explained how swaps and other derivatives work so that the reader will later understand their importance in the emergence of Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies. For now, it's swaps that brings us back to our story.

A Good Long Walk

SEFCON V was set to take place in Manhattan on Wednesday, November 12—just six days after I learned that I would not be permitted to speak there. Hundreds of industry executives and regulators were expected to attend and my colleague CFTC Chairman Tim Massad was giving the luncheon keynote address. I was one of the few Republicans in financial leadership roles who had vocally supported the swaps reforms in Dodd–Frank and, in particular, its mandate that swap transactions occur on CFTC registered swaps execution facilities. I had an important contribution to make to the discussion.

Preventing me from attending was an ethics rule adopted by the Obama administration. It bars senior and cabinet-level administration officials from speaking at events sponsored by a former employer unless said official receives a waiver. The idea is to prevent senior officials from using their government office to benefit a former firm by appearing at that firm's events to drive attendance and admission fees.

I thought I would easily qualify for a waiver. First, I was never a paid employee of the WMBAA, only an unpaid, voluntary board member.

Second, the ethics rule in question, by its terms, applied only to executive branch agencies, not independent agencies like the CFTC. Although I had signed a pledge to comply with the rule because Obama personnel staff had asked me to, the underlying order was never intended to reach officials serving in non-executive branch, independent agencies like the CFTC.

Third, at my request, the WMBAA had not announced my attendance at SEFCON V and, therefore, my appearance could not have boosted paid attendance.

Finally, I was both an outspoken supporter of the Dodd–Frank reforms that created the SEF rules and one of the most knowledgeable government officials available to address the industry.

Still, I had signed the waiver, I was relatively new to my post, and once the White House says no, it is exhausting to find the relevant official and make an appeal on short notice. We needed a workaround.

I called my staff together, including my cautious and savvy chief of staff, Jason Goggins; legal counsel, Amir Zaidi; and senior legal counsel, Marcia Blase. Ever meticulous, Marcia explained how several weeks before she had inquired about obtaining a White House waiver with the CFTC's Chief Ethics Officer, a former Obama administration lawyer who had helped craft the pledge itself. That lawyer had seemed optimistic about getting the waiver, according to Marcia, but now, with four business days to go, the White House had surprised us with a “no.”

My staff was upset. Jason, especially, was spoiling for a fight. He wanted to challenge the CFTC Ethics Officer by demanding written confirmation of the White House denial. Marcia recounted her conversation with the ethics lawyer. My head hurt. I needed to take my own counsel. I said I would step out, get a sandwich, and that we should reconvene in an hour.

I strode through the hall of the CFTC’s ninth-floor executive suite past the black-and-white photos of a dozen former agency chairs and then, further down the hall, past the living color photos of the current commissioners. I rode the elevator down to the red marbled lobby of the CFTC headquarters and walked past the uniformed security guards before the large etched-glass CFTC seal. I exited the building onto 21st Street in Northwest Washington—an area north of Foggy Bottom and south of Dupont Circle.

Returning to a lifelong habit of peripatetic processing of important information, I began to walk fast. I headed north on 21st Street across New Hampshire Avenue. The neighborhood quickly changed from modern rectilinear glass office blocks to hexagonally flared, flower-boxed Victorian residences. I paced onward toward Massachusetts Avenue and turned left on Embassy Row. I walked past the Cosmos Club,11 where I had lived for six weeks the summer before while looking for an apartment.

I saw no upside to wasting time trying to reverse the denial of the waiver. The issue was how to deliver my message. The speech was ready. It was good, and it was important. It would be my first major speech on US soil as a CFTC Commissioner. It was an important opportunity to define myself and my agenda to a critical audience of peers in the New York financial community. I intended to reiterate my pro-reform credentials as a supporter of the swaps trading provisions of Title VII of the Dodd–Frank Act. At the same time, I planned to criticize the CFTC's peculiar implementation of certain of those provisions.

As I turned right, past the bright magenta-flowered myrtle trees of the Cosmos Club garden, and walked up Florida Avenue, I reflected on the fact that I may have been one of the most long-standing advocates of swaps market reform from either political party to serve as a CFTC commissioner.12 In 2000, when I first left New York law practice and entered the swaps industry, I was struck by the fact that, unlike in most overseas trading markets, swaps brokerage was not a regulated activity. This omission hurt the professionalism of US swaps markets compared to overseas markets, in my view.

Not long after, I became a supporter of what's known as “central counterparty clearing” of swaps—that is, the practice in which a central party acts as an intermediary between buyers and sellers. In many derivatives markets, for instance, a clearinghouse serves this role, acting as the buyer to every seller and the seller to every buyer. The clearinghouse also ensures that the parties honor their contractual obligations over time.

I had seen firsthand how the emergence of central clearing in the energy swaps market increased trading liquidity and market participation. Before the financial crisis, I had led an effort at a brokerage called GFI Group to develop a central counterparty clearing facility for credit default swaps. That initiative led to the formation of IceClear Credit, which today is the world's leading clearer of those products.

I also was a supporter of greater swaps transparency. My experience from the 2008 financial crisis was that financial regulators lacked visibility into the risk that large financial institutions could fail due to inability to pay their financial obligations. Undoubtedly, swaps and other derivatives contributed to the financial crisis through the writing of credit default swaps protection by the giant insurance company American International Group, known as AIG. An equal or greater contribution came from the opacity of another complex product—not a derivative—that made its way onto bank balance sheets: collateralized mortgage obligations. While some derivatives transactions had come to be centrally recorded, what was missing was reliable information for both regulators and the marketplace about the true value and risk of these instruments. Government authorities simply did not have sufficient data to accurately assess the implications of the potential failure of a Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers or AIG on derivatives counterparties throughout the financial system. They had little ability to assess the true danger—short of telephone calls in the middle of the crisis to specialized firms like GFI, where I was working at the time. That was just not good enough.

So, by the time Congress began drafting the bills that would become Title VII of the Dodd–Frank Act, I was already a vocal advocate for its three key pillars of swaps market reform: regulated swaps execution, central counterparty clearing, and enhanced swaps transparency through data reporting. As a Republican, my support for Dodd–Frank's swaps provisions made me a maverick in my party, which had mostly opposed the legislation. Yet, as a businessperson, I believe that intelligently regulated markets are good for the economy and job creation. My support for parts of Dodd–Frank was driven by my professional and commercial experience, not academic theory or political ideology. These particular swaps reforms were organic and not terribly radical.13 Market participants were already at work on two of them—without government urging—when the crisis hit. Completing all three reforms correctly was the right thing to do. That is why I supported swaps market reform.

Generally, in the American system, after Congress passes a law requiring new regulation by a federal agency, the agency designs and implements the rules. That gives regulators a lot of clout. No matter how good a law sounds on paper, whether it actually improves anything hinges on how the regulations implementing it are drafted. The devil is in the details.

In a remarkably short time after the passage of Dodd–Frank in 2010, the CFTC implemented most of its mandates. By the time I joined the