Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

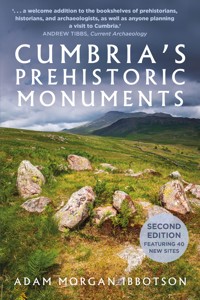

Cumbria is a land built from stone. Whether it is Hadrian's Wall, Kendal Castle or the beautiful fells of the Lake District – for thousands of years people have found a certain elegance and utility in stone. Nestled amongst these common relics are a multitude of massive stone monuments, built over 3,000 years before British shores were ever touched by Roman sandals. Cumbria's 'megalithic' monuments are among Europe's greatest and best-preserved ancient relics but are often poorly understood and rarely visited. This updated and revised edition of Cumbria's Prehistoric Monuments aims to dispel the idea that these stones are merely 'mysterious'. Within this book you will find credible answers, using up-to-date research, excavation notes, maps and diagrams to explore one of Britain's richest archaeological landscapes. Featuring stunning original photography and illustrated diagrams of every megalithic site in the county, Adam Morgan Ibbotson invites you to take a journey into a land sculpted by ancient hands.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 241

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2021

This edition published 2024

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Adam Morgan Ibbotson, 2024

Photos and diagrams by the author.

The right of Adam Morgan Ibbotson to be identified as the Authorof this work has been asserted in accordance with theCopyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprintedor reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic,mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented,including photocopying and recording, or in any informationstorage or retrieval system, without the permission in writingfrom the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 75099 763 8

Printed in Turkey by Imak.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

When stone speaks,

just listen.

Let rain wash words

to sore soil.

Let sun bake old time;

tomes of bones.

Let lichen’s text come

and grow.

– ‘Unnamed Megalith’,

Simon De Courcey

CONTENTS

Introduction

A Quick Guide Before You Start

Chapter One

The Central Lakes

Chapter Two

The Irish Sea

Chapter Three

South Cumbria

Chapter Four

East Cumbria

Chapter Five

Penrith

Bibliography

INTRODUCTION

Britain’s prehistoric monuments offer a glimpse into the lives and religious customs of Europe’s earliest settled communities. They are the remnants of the cultures that lived in the British Isles over two distinct periods: the Neolithic and the Bronze Age. Taken together, these eras, spanning between 4000 and 700 BC, could be considered a prehistoric golden age. It was during this golden age, thousands of years before Roman sandals touched British shores, that some of Europe’s grandest monuments were created.

Despite the global appreciation of Britain’s prehistoric monuments, only a select few sites are known to the public. Stonehenge, for instance, has become the mascot for the Stone Age, appearing in popular culture all around the globe. But while Stonehenge and its surrounding landscape are impressive, many people are unaware that the best-preserved examples of such monuments exist at Britain’s extremities. Among such areas are Cornwall, Scotland, Western Ireland, Wales, and, as shown in this book – Cumbria.

Cumbria is the least densely populated county in England and is perhaps better known for its landscapes than its inhabitants. While Cumbria’s cultural heritage may appear remote to some, its isolation has played a key role in the preservation of monuments of extreme antiquity. Without the need to fill every corner of the land with housing developments, supermarkets, or motorways, ancient monuments – the large and the small – have survived over the millennia. They stand as resolute as they did thousands of years ago, time capsules for a world so different it can seem alien.

It is thanks to this remoteness that Cumbria has retained some of the most breathtaking prehistoric monuments in the world, a combination of massive stones and stunning views. In England, archaeological sites of such importance are seldom found in such beautiful settings. Yet here, from the fells of the Lake District to the shores of the Irish Sea, you can find yourself alone with nothing but a stunning view and an ancient stone monument. For those who have experienced the droves of tourists that accompany any visit to Stonehenge, this seclusion will be appreciated.

In this book, you will find an assortment of monuments, some on the tourist trail and others virtually unexplored. You may find that the best sites lie off the beaten track, in the most unexpected areas, which is terrific if you enjoy an adventure into the unfamiliar. I invite you to take a journey thousands of years back into our past, to an era sculpted by ancient hands.

These are Cumbria’s Prehistoric Monuments.

A QUICK GUIDEBEFORE YOU START

Since the seventeenth century, academics and institutions across Europe have worked to further our understanding of our prehistoric past. When speculating upon relatively simple stone arrangements, it was oftentimes necessary to coin new terms to differentiate between them. Therefore, a unique archaeological jargon has emerged. Take the paragraph below as an example:

A mid to late Neolithic megalith stands at the centre of the henge monument, next to which is an Early Bronze Age kerbed cairn. Decorated with intricate cup marks, its position at the end of the avenue makes it the perfect spot to gaze out onto the cairn field.

If you understand this paragraph, you should turn the page and continue. But for the uninitiated, please do take note of the small glossary on the following page.

Throughout this book, the author will explain the historical context behind each site and explain their proposed functions. There may be times when it is necessary to refer to this glossary, and that is without shame. Despite appearing crude on their surface, these monuments are vestiges of a complex prehistoric society we have yet to fully understand.

In describing these sites, the author will be crediting those who have studied and explored Cumbria’s prehistoric monuments. However, there may be times when phrases along the lines of ‘some speculate’ and ‘many have theorised’ are used. In such cases, complex multi-source theories are condensed into small summaries for the sake of easy readability. The sources for such theories are written in the bibliography at the back of the book, which lists all texts referenced, as well as the databases accessed during research.

Indeed, this book does not attach undeniable dates and answers to each of the monuments listed. Instead, it aims to provide information on what is known about each site, and the theories this has produced. I would advise the academically inclined among the readership to explore the avenues of my research (i.e., check my sources).

Author’s Note: Often, prehistoric monuments are situated in hard to access areas, be it physically or legally. This book serves to inform the reader of the extent of the prehistoric monuments in Cumbria; it is not an invitation to trespass on or disturb any of the areas detailed in its pages. Do not trample cairns, do not lift stones, and do not use metal detectors at these sites; doing so is against the law, and is generally frowned upon. Do not do it.

TERM

DEFINITION

Barrow

Any variety of mound intended to inter the dead. Same as a ‘tumulus’.

Bell beaker

A non-funerary pottery vessel dating to the Early Bronze Age, typically 12–30cm tall with a fluted top.

Burial cairn

A mound of stones created to mark burials.

Burial circle

A stone circle with a central burial cairn.

Cairn-field

An expanse of land with several prehistoric cairns.

Cap stone

A stone that covers a cist burial.

Cist

A small, stone-built coffin-like box or ossuary used to hold the bodies of the dead. Typically found within burial cairns.

Crag

A steep or rugged cliff or rock face.

Cremation cemetery

An area where bodies were cremated and buried, either in coffins or cists.

Crop marks

Patterns found in crop fields, due to differing levels of soil depth. Lighter marks are caused by shallow soils, darker marks signify trenches or pits.

Cup and ring marks

A style of rock art typical of the early to mid-Neolithic (3800–2750 BC) consisting of chiselled rings and dots on a rockface.

Cursus monument

Vast, cigar-shaped earthen enclosures created near the beginning of the Neolithic (est. 3800 BC).

Dyke

A man-made trench, often used in prehistoric and medieval times to delineate land boundaries.

Flint

A form of quartz used throughout the stone age to sculpt cutting tools.

Henge

An earthwork typical of the Neolithic period, consisting of a roughly circular or oval-shaped bank with an internal ditch surrounding a central flat area.

Hut circle

The foundation of a prehistoric roundhouse, typically circular stone walls with a single entrance and a cobbled interior.

Kerb stones

Stones holding a mound of stone or earth in place around its outside.

Polished axe

A well-honed stone axe typically dating to the Neolithic period, although earlier examples have been found.

Portal

A term used to define large stones that appear to form an entrance.

Solstice

The day when the sun reaches its highest point. This occurs twice a year, in summer and winter, marking both the longest (summer) and shortest (winter) days of the year.

Stone avenue

Two rows of stone erected parallel within the landscape.

Stone circle

A circular arrangement of stones.

Stone row

A single row of stones that forms a line in the landscape.

Survivor’s bias

A logical error made by concentrating on items that survive today, ignoring non-surviving examples.

Tumulus/tumuli

Any variety of mound intended to inter the dead. Same as a ‘barrow’.

MOUND VARIETY

DESCRIPTION

Kerbed barrow

A style of burial monument common in the Early Bronze Age (2500–1800 BC). A circle of stones around the base of a mound of earth or stone.

Bowl barrow

An earth-covered tomb with a resemblance to an upturned bowl (3200 BC–AD 700).

Clearance cairn

An uneven heap of stones removed from farmland. Does not contain burials.

Long barrow

A long earthen tumulus. Typically made during the early Neolithic (4000–3200 BC).

Long cairn

A rare long stone tumulus. Made during the early Neolithic (3800–3200 BC).

Passage tomb

A mid-Neolithic burial mound, with a narrow access passage made of large stones (3400–2800 BC).

Platform cairn

An Early Bronze Age burial cairn; low lying with a flat top. Possibly a converted ring cairn.

Ring cairn

A circular enclosure made from loose stones, can be kerbed. Sometimes known as ‘cremation cemeteries’. If topped with a stone circle, they are known as ‘embanked stone circles’.

Round cairn

Large stone mounds covering single or multiple burials. Typically made during the Bronze Age (2500–800 BC).

STONE CIRCLE VARIETY

DESCRIPTION

Cumbrian Circle

Large uncluttered megalithic enclosures, similar to henges, and formed using megalithic stones. Typically aligned to the mid-winter solstice sunrise or sunset.

Burial Circle

An Early Bronze Age enclosure used during funerary activity. A small stone circle approximately 12–16m in diameter, surrounding a small burial cairn. A variant of a ring cairn local to the west coast, similar to the concentric stone circles of eastern Cumbria.

Concentric Circle

An Early Bronze Age enclosure used during funerary activity. A stone circle at the centre of another. The central circle is always a kerbed cairn. A variant of a ring cairn local to the Eden Valley, similar to the burial circles of eastern Cumbria.

Embanked Stone Circle

An Early Bronze Age enclosure used during funerary activity. A cobbled ring of loose stones with a circle of standing stones erupting from the top.

Kerbed Ring Cairn

An Early Bronze Age enclosure used during funerary activity. A cobbled ring of loose stones kerbed on their inner and outer circumference with megalithic stones.

THE NEOLITHIC – 4200–2500 BC

NEO: NEW OR OF RECENT MANUFACTURE.

LITHIC: OF THE NATURE OF OR RELATING TO STONE.

What defines the Neolithic period, and when it began, are topics of endless discussion. Therefore, please pardon the condensed theory that follows. There remains much to learn about this complex subject, with debates ongoing about the spread of farming techniques, monument construction, and the role of migrating societies.

Around 6200 BC, the world warmed. Wildfires swept through Europe, and land once dominated by forests became clear and fertile. Populations fleeing a drought-ridden Near East slowly migrated west, bringing innovative farming techniques, fixed settlements, and complex religious systems with them. By 4200 BC, the French and Spanish coasts were already home to monument-building cultures. Britain, on the other hand, remained largely wild, and was among the last regions in Western Europe permanently settled by farming communities.

Prehistoric monuments first emerged in Cumbria in the ‘Early Neolithic’ period (c.4000–3200 BC. During this era, circular ritual enclosures, known as causewayed enclosures, were built across the region’s uplands. Large communal tombs known as long cairns were built on adjacent hillsides. Unlike other regions of England, such sites were predominantly built using stone, either megalithic blocks or rubble.

People had yet to dominate the British landscape in the Early Neolithic, and most of the landscape remained forested. Monuments of the period often demonstrate an emphasis on nearby features, suggesting views of distant landscapes were obstructed by woodland. However, with the dawn of agriculture and fixed settlement, it was only a matter of time before people would begin to clear the British landscape.

Neolithic people cleared many forests in Britain. This was a crucial necessity, as they would need to relocate repeatedly and clear forests in pursuit of fertile soils. At the same time, the previous inhabitants of the British Isles – the ‘Mesolithic hunter-gatherers’ (c.8000–4000 BC) – saw a steep decline in population. Still, it seems that Early Neolithic farmers lived and bred with these early folk. DNA evidence, collected from tombs, has shown Mesolithic genetics survived as a form of ‘elite’. Inbreeding to preserve their lineages, Neolithic society may have been dynastic. This is further evident in Early Neolithic artefacts, which appear to have been passed down through generations. For example, Early Neolithic ‘Langdale stone axes’ from the Lake District (c.3400 BC) have been found deposited within much later burials in Yorkshire, sometimes as late as the Early Bronze Age (a gap of more than 1,000 years).

A NEOLITHIC AXE HEAD FROM LANGDALE, EST. 3800–3200 BC.

As the era advanced into the mid to late Neolithic period (c.3200 to 2500 BC), the use of standing stones increased, and the design of enclosures shifted towards a circular shape. These enclosures are believed to have served as religious ceremonial centres, and they were often aligned towards the solstice sun. During this era, burial monuments also underwent a change, adopting the round shape and featuring chambers capable of accommodating multiple bodies. The practice of interring disarticulated skeletons, where limbs were removed prior to burial, was common during this period. As a result, Neolithic burial chambers are frequently found to contain an assortment of jumbled bones. People later removed bones from these graves to use in rituals.

Rock art is another indicator of the Neolithic period. Motifs, such as ‘cup and ring marks’ (c.3600–3200 BC) and ‘passage tomb art’ (c.3200–2800 BC), are found across Cumbria. Many stone circles, cairns, natural outcrops, and burial chambers exhibit carvings. Examples of Irish-style passage tomb art are, curiously, common in Cumbria, and can be found carved onto several megalithic tombs. Cumbria contains the densest collection of passage tomb art in England, and is, therefore, crucial to our understanding of migrations during that time.

THE EARLY BRONZE AGE – 2500–1600 BC

BRONZE: AN ALLOY METAL CONSISTING PRIMARILY OF COPPER AND TIN. AGE: A DISTINCT PERIOD OF HISTORY.

The Early Bronze Age was a continuation of the Neolithic period and signalled the end of the Stone Age, marking the beginning of significant cultural advancements in Britain. It was not a sudden or definite event, but rather a gradual transition as metalworking techniques spread across Europe via migration and trade. Despite its name, the Bronze Age saw a spike in all metal production, leading to a surge in the use of bronze, copper, and gold.

At the conclusion of the Neolithic, Britain seems to have been a victim of several cataclysmic events. Once thriving Neolithic farming communities underwent a significant decline, and it is estimated that as much as 90 per cent of the population was replaced by newcomers. The cause of this sudden change remains a mystery. It is unclear whether it was a result of famine, disease, or even acts of genocide. Genetic evidence of the Neolithic farmers was erased in some regions. Nevertheless, stone arrangements from the Early Bronze Age continued to exhibit a similar complexity. For example, the construction of Stonehenge began during the Neolithic, but underwent a significant renovation during this pivotal transitional period, with its lintels being lifted and repositioned.

While pottery making did begin in earnest during the Neolithic, the dawn of the Early Bronze Age would kickstart a revolution in how pots were created. Bronze Age migrants introduced ‘bell beakers’, decorated vessels shaped like church bells. Believed to have developed in Iberia, in a region near modern-day Portugal, the bell beaker would come to dominate Western Europe. These vessels are linked to the so-called ‘Beaker People’. Genetic evidence has shown these people to have migrated westwards from Eastern Europe, possibly adopting the beaker from an invasion of Iberia around 2900 BC. By 2500 BC, these warlike people had arrived in Britain, bringing their beaker, their warfare, their language, and their metallurgy, with them.

A GOLDEN LUNULA DATING TO THE BRONZE AGE. ONE OF ONLY THREE FRAGMENTS FOUND IN ENGLAND. ESTIMATED 2200–1700 BC AND FOUND DURING AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL DIG NEAR BAMPTON. LUNULAS ARE TYPICALLY FOUND IN MAINLAND EUROPE AND IRELAND.

Despite their strong ties to their respective styles of pottery, nobody knows the purpose of Early Bronze Age beakers. Flared around their opening and with a narrow base, they are distinct from other pots. They are not often found to contain cremated remains but are instead buried next to the dead, empty. This style of burial is a telltale sign of Beaker activity, having a body buried in a foetal position, often next to flint or bronze weapons, and beakers. These are known as ‘beaker burials’. Partly due to these lavish burial practices, researchers have speculated this period was lorded over by powerful chieftains or religious elites.

Despite the cultural chaos, prehistoric monuments saw much activity during this period. Like the Victorian Era’s Gothic Revival, inspired by mediaeval architecture, the Early Bronze Age saw something of a megalithic revival. Indeed, the ring cairns, an Early Bronze Age a variety of stone circle, is abundant across Cumbria. Ring cairns provided a space for preparing the dead for burial. Excavations have revealed that ring cairns were used for cremations, excarnations (the removal of flesh from bodies), and later, burial.

THE MID TO LATE BRONZE AGE – 1600–700 BC

The Mid to Late Bronze Age was a major, if less dramatic, turning point in Britain’s timeline. It seems that by 1600 BC, community-led megalithic construction had ceased. Instead, Mid-Bronze Age people seem to have focused on everyday domestic activities – the important things in life: food, safety, and shelter. The most common archaeological sites relating to this period are farming settlements, and boundary earthworks. Unfortunately, due to the absence of any written records from the period, the cause of this momentous cultural shift remains unknown.

However, using comparisons to world history, it would seem a change in their social structure may have been to blame. The Mayans of Central America, for instance, saw the emergence of their Golden Age (ad 600) when ruled by powerful, idolised leaders. Britain would also be graced with villas, roads, and massive defensive structures with the arrival of the Roman Empire in AD 43. In both cases, the collapse of a dominant social hierarchy led to the mass abandonment of construction projects, and a void in the archaeological record (i.e., the Mayan Collapse, or the Dark Ages). Indeed, powerful empires sometimes fall like dominoes, dragging everything down with them. For the British Bronze Age, this may have translated to fewer chieftains dictating what people should, or could, do. Therefore, fewer large-scale ceremonial monuments were constructed.

The Mid-Bronze Age in Cumbria saw a gradual increase in small, individual burials. Unlike earlier graves, which often contained lavish burial goods, such as weapons or jewellery, Mid-Bronze Age graves tend to be more restrained. Individual burials became more common, and rather than large mounds, burial urns were placed in pits. These urns are often found in designated areas, known as urnfields, hallowed grounds comparable to modern graveyards. Interestingly, Bronze Age urnfields are sometimes located near or within Neolithic sites, suggesting a form of ancestor worship.

CHAPTER 1

THE CENTRAL LAKES

It is easy to see why millions of people flock to this UNESCO World Heritage Site every year. The Lake District is home to England’s largest lakes and highest peaks, making it both a walker’s paradise and a photographer’s dream. For obvious reasons, this is a region that has inspired artists for thousands of years, with some of its prehistoric monuments ranking among the oldest in Britain.

Few landscapes garner as much attention as those in the English Lake District. Alongside Cornwall, Dartmoor, and the Yorkshire Dales, the Lake District is often rated among England’s wildest, and most scenic regions. The romantic passion for the region’s mountains and lakes, well-ingrained in English culture since Wordsworth, has given birth to the idea that this land, alien to the densely populated cities of the south, has always been admired for its beauty. A nationally important space for urban dwellers to seek an idealised concept of English ‘nature’.

For their part, the marketing departments at the Lake District National Park, as well as the National Trust, promote the idea that otters, birds of prey, and other wildlife, are spotted commonly here. Marketing material for the Lake District often displays images taken from misty early morning fell tops, fortuitously obscuring the manmade structures littering the lower valleys. Scanning the tourist literature may lead one to believe the Lake District is an untamed natural hotspot; a counter-urbanism, where visitors can find refuge from modernity. This is, however, not true.

The modern Lake District is far from a refuge from modernity. Peek behind the curtain – represented here by chocolate box villages, snow-capped fells, and the rare encounter with wildlife – and you will find a familiar story of human exploitation of the landscape. A story, not necessarily as old as time, but certainly as old as the Early Neolithic (4000 BC).

The prehistoric landscapes of the Lake District are divided by England’s tallest mountains, and despite their proximity, they can feel worlds apart. Take Troutbeck and Grasmere as an example. Only a spine of mountains separates these valleys, yet the prehistoric monuments within them are distinctive. Today, venturing from valley to valley only requires a five-minute drive, but without cars, roads, or electronic maps, several hours of strenuous hiking would be required to journey between them. To put this into context with a modern equivalent, an hour’s commute is the difference between living in London or Birmingham, distinct settlements with their own dialects and landmarks.

LANGDALE

The Great Langdale Valley extends 12,000 acres from Elterwater to the Mickelden Valley, passing through Skelwith Bridge, Elterwater, and Chapel Stile.

When Britain entered the Early Neolithic period around 3800 BC, one of the biggest innovations was the popularisation of the polished stone axe. These axes were well honed and polished, demonstrating a high level of technical skill. Their discovery within archaeological sites often indicates the settlement of Neolithic people and the existence of a nearby prehistoric trade network.

But where did they come from?

During the early twentieth century, different styles of stone axe were catalogued and numbered depending on the stone they were created from. Among the most numerous were the ‘Group VI’ axes, a variety created using a fine-grained greenstone, known as Lingmell tuff. In the 1930s, these axes were traced to Langdale, hinting that this quiet valley hid an exciting secret.

Langdale is now generally believed to represent the earliest indication of the Neolithic revolution in Cumbria. It was here that a stone axe industry is believed to have been in operation for more than 500 years, from 3800 to 3200 BC. A considerable portion of the Neolithic period. Axe heads originating from Langdale have been unearthed in Scotland, London, Ireland, and particularly in East Yorkshire. This may suggest Early Neolithic Cumbria was deeply connected to the rest of the country via trade networks, with a major export being axe heads sourced from Langdale.

Langdale is perhaps the backbone – the true heart of innovation – of almost all prehistoric monuments across Cumbria.

THE AXE FACTORY

The Axe Factory, a collection of Neolithic quarries found across the Langdale Pikes, is estimated to have produced 21 per cent of all polished axe heads found throughout Britain.

The clearest physical evidence for the Axe Factory is a man-made cave on the Pike of Stickle. However, this was far from the only quarry. Worked stone outcrops have been identified all along the hills surrounding Langdale, and axe heads have been discovered on Harrison Stickle, Scafell Pike, and Glaramara. On Glaramara and Harrison Stickle, indications of knapping have been found. This was the process of chiselling the raw stone into shape, creating semi-honed ‘roughout’ axe heads. Axes were often traded as roughouts, then honed by the communities that received them.

Since the 1930s, researchers have debated why people would climb these treacherous hills to quarry and knap. The same stone is both easier to source and more abundant elsewhere, yet the stone found at this location was evidently sought after. Despite Lingmell Tuff appearing in easier to source locations, it is on a treacherous scree slope between Pike O’ Stickle and Loft Crag that we find the clearest indication of quarrying. The steep-sided fells would make Langdale a difficult place to traverse and an even more challenging location for quarrying. Almost all the quarries are found on such terrain, some near vertical drops, which begs the question: why Langdale?

It has long been suspected that Langdale axes were sacred objects, with the toil involved in their sourcing contributing to their value. If this was the case, then we can presume that these were driven, spiritual people who venerated their landscapes. Their dedication to quarrying here highlights just how deep was the connection between their landscape and their religious beliefs. This is a crucial connection to understand when we study the monuments of Cumbria.

Once knapped and polished, Langdale axe heads were of astounding quality. Using a variety of honing techniques, they were polished to make them smooth, and the blade was sharpened to a cutting point capable of felling trees. The weight of the head would have been enough to help automate the labour, and just relaxing your arm would have allowed for a satisfying and efficient swing.

THE SCREE SLOPE BETWEEN PIKE O’ STICKLE AND LOFT CRAG.

Debate as to the purpose of polished axes is almost continuous. While they are practical tools, they are often found near Neolithic and Early Bronze Age graves, as well as ritual sites like stone circles. During the Neolithic period, numerous axe varieties were created, some for ceremonial use and others for practical use. Given the long-range trade of these axes, they seem to have been prized and almost certainly created for ceremonial use. Indeed, these were neither jagged flints nor crude lumps of rock. They were works of art, created with their aesthetic value at the forefront of their design.

SUNRISE AT HARRISON STICKLE, AS SEEN FROM STICKLE TARN.

Langdale axe heads are often discovered near water sources, such as the River Thames or Irish Sea. The Furness Peninsula, for instance, is a hotbed for axe head finds. During the Neolithic, much of Cumbria was covered in dense forest, making the land hard to traverse by foot. Therefore, it is theorised that prehistoric Britons used boats, both over rivers and at sea (becoming infamously gifted at seafaring by the time the Romans landed in AD 43). Some believe that an overseas trade route existed along the coast, dispersing the highly sought-after Langdale axe heads across Britain. This would explain how such a large number of these axes ended up in Ireland and London.

Despite the Axe Factory having ceased production by 3200 BC (according to theory), there appears to have been interest in the hills around Langdale through to the Bronze Age. Numerous small cairns dot the valley below the Pike of Stickle, possibly Bronze Age burial cairns. There is also what appears to be an Early Neolithic long cairn at the mountain’s base.

Author’s Note: Several Langdale axe heads can be found in the British Museum, but closer to home, you can find an excellent display of these axes at Keswick Museum, Kendal Museum, and Tullie House Museum in Carlisle. Elsa Price, the Curator of Human History at Tullie House Museum & Art Gallery, gave me the opportunity to handle and photograph the beautifully crafted axe head pictured on page 15. Also, the Langdale Pikes and their surrounding area can be unstable and perilous, so make sure to be well prepared if you intend to visit.