Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

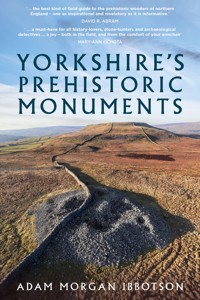

Yorkshire is a testament to the enduring power of stone. From the imposing walls of Skipton Castle to the ruins of Whitby Abbey, the inhabitants of England's largest county have evidently found both beauty and practicality in the use of stone for thousands of years. But amidst these well-known and relatively recent historic sites lies a host of monuments of extreme antiquity, built up to six thousand years ago. Drawing upon new research, excavation notes and diagrams, Yorkshire's Prehistoric Monuments aims to reveal the secrets of one of Britain's richest archaeological landscapes. Yorkshire's standing stones, burial cairns and extensive earthworks are among Northern Europe's best-preserved prehistoric relics. Featuring original photography and newly illustrated diagrams compiled over several years of travel and writing, Adam Morgan Ibbotson invites you to take a journey into a landscape sculpted by ancient hands.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 241

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2023

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Adam Morgan Ibbotson, 2023

Photos and diagrams by the author.

The right of Adam Morgan Ibbotson to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 8039 9576 2

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Back in the autumn of 2019 I was sifting through old photos, editing a few I took of Castlerigg Stone Circle for print. During that fateful period of editing, I conjured up the idea of creating a simple guidebook for the public, detailing each prehistoric monument in the Lake District. Over 300 prehistoric sites, a nationwide lockdown, and 80,000 words later, I can confidently say that I have learned a thing-or-two about English prehistory… Even then, there remains much to learn. This is made abundantly clear as I reflect upon the individuals who have helped and supported me over the past four years.

First and foremost, I express my sincere gratitude to the numerous academics who have generously assisted me. Whether through casual conversations or persistent email inquiries, their guidance and support have been invaluable. I extend special appreciation to Mark Brennand of Cumbria County Council, whose expertise and willingness to respond to my queries fuelled my thirst for knowledge. Additionally, archaeologist and all-around great man Peter Style, graciously proofread my first book and imparted a wealth of information in the process. I am particularly indebted to my university supervisor Professor Kevin Walsh, whose teachings significantly enriched my understanding of prehistoric landscapes. I must also thank David R. Abram and Mary-Ann Ochota for their support of this book. Their remarkable contributions to the field of popular archaeology have deeply influenced me in recent years.

I am of course also thankful for the assistance from my friends and family during the creation of my two books. Their unwavering encouragement and support played a significant role in my journey. Field trips became unforgettable with the companionship of my friends Jamie Booth, Matt Staniek, Chris Shreiber, and Jay A. There was also the support of my wonderful partner Keziah, as well as my parents Ian and Glynis. All these people were essential in visiting many of the sites featured in this book, joining me on ventures along rain drenched country roads and boggy moors in search of the most isolated of sites. I would also be remiss not to express overdue gratitude to Elsa Price, Marnie Calvert, and Professor Terence Meaden for their early contributions and support, which greatly enriched my first book, Cumbria’s Prehistoric Monuments.

CONTENTS

Introduction

A Quick Guide Before You Start

Chapter One

North York Moors

Chapter Two

The Vales of Mowbray and York, the Heart of Neolithic Yorkshire

Chapter Three

The Dales and Craven

Chapter Four

East Riding – The Yorkshire Wolds

National Grid References

Bibliography

We might imagine limits to a difficult landscape;see grikes and clints stitched by bold saplings.

We might value history’s deep mulch, know theeconomy of stones; balky vaults of old memory.

An excerpt from ‘An Economy of Stones’ by Simon De Courcey.

INTRODUCTION

The prehistoric monuments of Britain offer a remarkable glimpse into the daily life and religious practices of Europe’s earliest settled communities. They are the remnants of cultures that inhabited the British Isles during two distinct periods: the Neolithic and the Bronze Age, between 4000 BC and 700 BC. This span of time could be seen as a prehistoric golden age, thousands of years before the arrival of the Romans. It was during this epoch that some of Europe’s grandest monuments were created.

Despite the appreciation such monuments garner, the public generally recognises only a few sites. Stonehenge, for instance, has long been the global mascot for the Stone Age. Likewise, there are regions of Britain synonymous with prehistory. Orkney, Wiltshire, Cornwall and the Lake District are often discussed in relation to Britain’s prehistoric past. Indeed, of the thousands of stone monuments strewn across our countryside, it seems the majority exist at the isles’ western extremities. But this does not represent the full picture. Eastern England, particularly the area encompassing the historic counties of Yorkshire, saw the emergence of prehistoric cultures capable of creating vast, complex and often mind-bogglingly grand monuments.

Although most of Yorkshire’s population resides in cities, much of the county remains rural. The region’s upland moors, for instance, stretching from Whitby to Ingleton, have been perfect for the preservation of prehistoric monuments.

With a smaller population density, less land was swallowed by housing developments, trading estates and roads. In such areas, monuments both large and small have survived in relative isolation for upwards of 5,000 years. Among these are ancient landmarks, seldom found elsewhere in Europe, their rarity a result of their survival in the face of adversity.

Yorkshire has many beautiful landscapes, from the North York Moors to the limestone crags of the Dales. It is a county as rich in human history as other regions in the UK but its tales are often untold, its stories unwritten. Despite this lack of attention, the land is alive with the echoes of the past, as Yorkshire covers a vast expanse encompassing hundreds of treasures from prehistoric times. So, while the author of this book cannot provide an exhaustive list of sites in Yorkshire, this book will detail the majority of viewable and visitable prehistoric landmarks.

With standing stones taller than those in Wiltshire, burial monuments grander than those in the Lake District, and rock art more abundant than much of Europe, Yorkshire deserves to be acknowledged as the archaeological Eden it is. In this book, you will find an assortment of monuments, some on the tourist trail and others that are virtually unknown. You may find the best sites lay off the beaten track, in the most unexpected areas, which is terrific if you enjoy an adventure into the unfamiliar. I invite you to take a journey thousands of years back into our past, to an era sculpted by ancient hands.

These are Yorkshire’s Prehistoric Monuments.

A QUICK GUIDEBEFORE YOU START

Since the seventeenth century, academics and institutions across Europe have worked to further our understanding of Europe’s prehistoric past. When speculating upon relatively simple stone arrangements, it was oftentimes necessary to coin new terms to differentiate between sites. Therefore, an archaeological jargon has emerged. Take the paragraph below as an example:

‘The megaliths serve as a kerb around the barrow. At the centre of this chambered cairn is a cist covered by a capstone. Decorated with cup and ring markings, its position at the end of the cursus crop mark makes it the perfect spot to view the Class II henge.’

If you understand this paragraph, you should turn the page and continue. But for the uninitiated, please do take note of the small glossary on the following page.

Throughout this book, the author will explain the historical context behind these sites and their proposed functions. There may be times when it is necessary to refer to this glossary, and that is without shame. Despite appearing crude on their surface, these monuments are vestiges of a complex prehistoric society we have yet to fully understand.

In describing these sites, the author will be crediting those who have studied and explored Yorkshire’s prehistoric monuments. However, there may be times when phrases along the lines of ‘some speculate’ and ‘many have theorised’ are used. In such cases, complex multi-source theories are condensed into small summaries for the sake of easy readability. The sources for such theories are written in the bibliography at the back of the book, which lists all texts referenced, as well as the databases accessed during research.

Indeed, this book does not endeavour to attach undeniable dates and answers to each of the monuments listed. Instead, it aims to provide information on what is known about each site, and the theories this has produced. I would advise the academically inclined among the readership to explore the avenues of my research by checking my sources.

Author’s Note: Often, prehistoric monuments are situated in hard to access areas, be it physically or legally. This book serves to inform the reader of the extent of the prehistoric monuments in Yorkshire; it is not an invitation to trespass on or disturb any of the areas detailed in its pages. Do not trample cairns, do not lift stones, and do not use metal detectors at these sites; doing so is against the law, and is generally frowned upon. Do not do it.

TERM

DEFINITION

Barrow

Any variety of mound intended to inter the dead. Same as a ‘tumulus’.

Bell beaker

A non-funerary pottery vessel dating to the Early Bronze Age, typically 12–30cm tall with a fluted top.

Burial cairn

A mound of stones created to mark burials.

Burial circle

A stone circle with a central burial cairn.

Cairn-field

An expanse of land with several prehistoric cairns.

Cap stone

A stone that covers a cist burial.

Cist

A small, stone-built coffin-like box or ossuary used to hold the bodies of the dead. Typically found within burial cairns.

Concentric stone circle

At least one stone circle encircling another.

Crag

A steep or rugged cliff or rock face.

Cremation cemetery

An area where bodies were cremated and buried, either in coffins or cists.

Crop marks

Patterns found in crop fields, due to differing levels of soil depth. Lighter marks are caused by shallow soils, darker marks signify trenches or pits.

Cup and ring marks

A style of rock art typical of the early to mid-Neolithic (3800–2750 bc) consisting of chiselled rings and dots on a rockface.

Cursus monument

Vast, cigar-shaped earthen enclosures created near the beginning of the Neolithic (est. 3800 bc).

Dyke

A man-made trench, often used in prehistoric and medieval times to delineate land boundaries.

Flint

A form of quartz used throughout the stone age to sculpt cutting tools.

Henge

An earthwork typical of the Neolithic period, consisting of a roughly circular or oval-shaped bank with an internal ditch surrounding a central flat area.

Hut circle

The foundation of a prehistoric roundhouse, typically circular stone walls with a single entrance and a cobbled interior.

Kerb stones

Stones holding a mound of stone or earth in place around its outside.

Polished axe

A well-honed stone axe typically dating to the Neolithic period, although earlier examples have been found.

Portal

A term used to define large stones that appear to form an entrance.

Solstice

The day when the sun reaches its highest point. This occurs twice a year, in summer and winter, marking both the longest (summer) and shortest (winter) days of the year.

Stone avenue

Two rows of stone erected parallel within the landscape.

Stone circle

A circular arrangement of stones.

Stone row

A single row of stones that forms a line in the landscape.

Survivor’s bias

A logical error made by concentrating on items that survive today, ignoring non-surviving examples.

Tumulus/tumuli

Any variety of mound intended to inter the dead. Same as a ‘barrow’.

MOUND VARIETY

DESCRIPTION

Kerbed barrow

A style of burial monument common in the Early Bronze Age (2500–1800 bc). A circle of stones around the base of a mound of earth or stone.

Bowl barrow

An earth-covered tomb with a resemblance to an upturned bowl (3200 bc–ad 700).

Clearance cairn

An uneven heap of stones removed from farmland. Does not contain burials.

Long barrow

A long earthen tumulus. Typically made during the early Neolithic (4000–3200 bc).

Long cairn

A rare long stone tumulus. Made during the early Neolithic (3800–3200 bc).

Passage tomb

A mid-Neolithic burial mound, with a narrow access passage made of large stones (3400–2800 bc).

Ring cairn

A circular enclosure made from loose stones, can be kerbed. Sometimes known as ‘cremation cemeteries’. If topped with a stone circle, they are known as ‘embanked stone circles’.

Round cairn

Large stone mounds covering single or multiple burials. Typically made during the Bronze Age (2500–800 bc).

THE NEOLITHIC – 4200–2500 BC

NEO: NEW OR OF RECENT MANUFACTURE.

LITHIC: OF THE NATURE OF OR RELATING TO STONE.

There is ceaseless debate about what defines the Neolithic, and when the period began. As such, please forgive the abridged theory below. This is a complicated topic, wrapped up in archaeological, scientific and philosophical debate, with plenty left to learn.

Around 6200 BC, the world warmed. Wildfires swept through Europe, and land once dominated by forests became clear and fertile. Over the next several centuries, populations fleeing a drought-ridden Near East slowly migrated west. They brought innovative farming techniques, fixed settlements and complex religious systems with them. By 4200 BC, the French and Spanish coasts were already home to monument-building cultures. Britain, on the other hand, remained largely wild, and was among the last regions in Western Europe permanently settled by farming communities.

Prehistoric monuments first emerged in Yorkshire in the ‘early Neolithic’ period (est. 4000–3200 BC). During this era, vast elongated enclosures called cursus monuments were built across the region’s lowlands. Large communal burial mounds, such as long barrows, long cairns and bank cairns were built on adjacent hillsides.

People had yet to dominate the British landscape in the early Neolithic, and most of it remained forested. Early Neolithic monuments often demonstrate an emphasis on nearby landscape features, suggesting that views of distant landscapes may have been obstructed by woodland. However, with the dawn of agriculture and fixed settlement, it was only a matter of time before people would begin to clear the British landscape.

Neolithic people cleared many forests in Britain. This was a crucial necessity, as they would need to repeatedly relocate and clear forests in pursuit of fertile soils. At the same time, the previous inhabitants of the British Isles – the ‘Mesolithic hunter-gatherers’ (est. 8000–4000 BC) – saw a steep decline in population. Still, it seems early Neolithic farmers lived and bred with these early folk. DNA evidence, collected from long barrows, has shown Mesolithic genetics survived as a form of ‘elite’. Inbreeding to preserve their lineages, Neolithic society may have been dynastic. This is further evident in early Neolithic artefacts, which appear to have been passed down through generations. For example, Early Neolithic ‘Langdale stone axes’ from the Lake District (est. 3400 BC) have been found deposited within much later burials in Yorkshire, sometimes as late as the Early Bronze Age (a gap of over a thousand years).

As the era advanced into the mid to late Neolithic period, spanning from 3200 BC to 2500 BC, the use of megalithic standing stones increased, and the design of enclosures shifted towards a circular shape. These enclosures are believed to have served as religious ceremonial centres, as they were often aligned towards the solstice sun. During this era, burial monuments also underwent a change, adopting a round shape and featuring chambers capable of accommodating multiple bodies. The practice of interring disarticulated skeletons, where limbs were removed prior to burial, was prevalent during this period. As a result, Neolithic burial chambers are frequently found to contain an assortment of jumbled bones. People later removed bones from these graves to use in rituals.

Rock art is another indicator of the Neolithic period. Neolithic motifs, such as cup and ring marks (est. 3600–3200 BC) and passage tomb art (est. 3200–2800 BC), were common across northern England. Many stone circles, cairns, natural outcrops and burial chambers exhibit cup and ring marks. Examples of passage tomb art are rarer in Yorkshire, but they can be found carved onto some megalithic tombs overlooking the coast. Yorkshire contains one of the densest collections of Neolithic rock art in Europe. It is therefore crucial to our understanding of its context.

THE EARLY BRONZE AGE – 2500–1600 BC

BRONZE: AN ALLOY METAL CONSISTING PRIMARILY OF COPPER AND TIN.AGE: A DISTINCT PERIOD OF HISTORY.

The Early Bronze Age was a continuation of the Neolithic period and signalled the end of the Stone Age, marking the beginning of significant cultural advancements in Britain. It was not a sudden or definite event, but rather a gradual transition as metalworking techniques spread across Europe through migration and trade. Despite its name, the Bronze Age was a time of increase in all metal production, leading to a surge in the creation of bronze, copper and gold artefacts.

At the conclusion of the Neolithic era, Britain was witness to a cataclysmic event. Once thriving Neolithic farming communities underwent a significant decline, and it is estimated that as much as 90 per cent of the population was replaced by newcomers. The cause of this sudden change remains shrouded in mystery, as it is unclear whether it was a result of famine, disease or even acts of genocide. Genetic evidence of the Neolithic farmers was erased in some regions. Yet, interestingly, stone arrangements from the Early Bronze Age continued to exhibit a similar complexity. For example, the construction of Stonehenge began during the Neolithic, but it underwent a significant renovation during this pivotal transitional period, with its lintels being lifted and repositioned.

While pottery making did begin in earnest during the Neolithic, the dawn of the Early Bronze Age would kickstart a revolution in how pots were created. Bronze Age migrants introduced bell beakers, decorated vessels shaped like church bells. Believed to have developed in Iberia, in a region near modern-day Portugal, the bell beaker would come to dominate Western Europe. These vessels are linked to the so-called Beaker People. Genetic evidence has shown these people to have migrated westwards from Eastern Europe, possibly adopting the beaker from an invasion of Iberia around 2900 BC. By 2500 BC, these warlike people had arrived in Britain, bringing their beaker, their warfare, their language and their metallurgy with them.

Despite their strong ties to their respective styles of pottery, nobody knows the purpose of Early Bronze Age beakers. Flared around their opening and with a narrow base, they are distinct from other pots. They are not often found to contain cremated remains but are instead buried next to the deceased, empty. One popular theory suggests these vessels were beer jugs, placed beside the deceased to be carried over to a boozy afterlife. Indeed, this style of burial is a telltale sign of Beaker activity, having a body buried in a foetal position, often next to flint or bronze weapons and beakers. These are known as Beaker burials. Partly due to these lavish burial practices, researchers believe this period was lorded over by powerful chieftains or religious elites.

Despite the cultural chaos, iconic prehistoric sites saw much activity during this period. Like the Victorian era’s ‘Gothic Revival’, inspired by medieval architecture, the Early Bronze Age saw something of a megalithic revival. Many stone circles began their creation during the Neolithic but had their largest stones raised during the Early Bronze Age. Indeed, the cultures that settled in the British Isles would go on to inherit its traditions.

THE MID TO LATE BRONZE AGE – 1600–1000 BC

The mid to late Bronze Age was a major, if less dramatic, turning point in Britain’s timeline. It seems that by 1600 BC, community-led megalithic construction had ceased. Instead, mid-Bronze Age people were seemingly focused on everyday domestic activities – the important things in life: food, safety and shelter. The most common archaeological sites relating to this period are farming settlements and boundary earthworks. Unfortunately, due to the absence of any written records from the period, the cause of this momentous cultural shift remains unknown.

However, using comparisons to world history, it would seem a change in social structure may have been to blame. The Mayans of Central America, for instance, saw the emergence of their ‘Golden Age’ (AD 600) when ruled by powerful, idolised leaders. Britain would also be graced with villas, roads and massive defensive structures with the arrival of the Roman Empire in AD 43. In both cases, the collapse of a dominant social hierarchy led to the mass abandonment of construction projects and a void in the archaeological record (i.e., the Mayan Collapse or the Dark Ages). Indeed, powerful empires sometimes fall like dominoes, dragging everything down with them. For the British Bronze Age, this may have translated to fewer chieftains dictating what people should, or could, do. Therefore, fewer large-scale ceremonial monuments were constructed.

The mid-Bronze Age in Yorkshire saw a gradual increase in small, individual burials. Unlike earlier graves, which often contained lavish burial goods, such as weapons or jewellery, mid-Bronze Age graves tend to be more restrained. Individual burials became more common, and rather than large mounds, burial urns were placed in pits without a cist. These urns are often found in designated areas, known as ‘urnfields’, hallowed grounds comparable to modern graveyards. Interestingly, Bronze Age urnfields are sometimes located near or within Neolithic sites, indicating a continuation of beliefs and practices over time.

CHAPTER ONE

NORTH YORK MOORS

The North York Moors encompass 885km of hilly terrain, stretching from the A19 to Whitby. This expanse was formed over thousands of years, when glaciers scooped out wide valleys in the sandstone geology. Millennia of erosion shaped the rolling hills and vast valleys into a fertile highland region, with dense forests covering the hills. However, as evidenced by the swathes of barren moorland we see today, something changed.

During the Mesolithic era, when people relied on hunting and gathering, the moors remained lush with woodland. That was until 4000 BC, with the arrival of the early Neolithic, when England’s woodlands began to vanish. From that point on, the modern moorlands we know today took shape. People cleared the woodlands to create pastures and piled natural rocks into clearance cairns, forming vast cairn-fields to make room for ploughing. They reshaped the land like never before, making it habitable for pasture. This deforestation only accelerated during the Bronze Age, as the climate favoured settlement at higher altitudes.

Ironically, this sculpting in pursuit of farmable land is why these hills are seldom inhabited today. Millennia of decaying biomaterial from lost natural habitats have rendered the moor’s soils acidic, leaving only the hardiest plants and animals to thrive. It is for this reason that prehistoric monuments have survived so well across the national park. Urban development, for the most part, has veered far from the moors. Aside from the odd military base or stone cross, the Moors are something of a time capsule.

BILSDALE AND RAISDALE

Our journey commences in the picturesque Bilsdale and Raisdale Valleys, the westernmost access points into the North York Moors. Sitting between the Hambleton Hills and heights of Urra Moor, these are among the most sheltered of the North York Moors’ valleys. However, the same cannot be said for the prehistoric monuments in the region, which were built along the uplands. The majority of these are Early Bronze Age burial mounds, built in rows along the crests of the moors. Round cairns, circular stone-built burial mounds, are particularly prevalent in Bilsdale.

Wholton Moor, Live Moor, Cringle Moor and Cold Moor are all dotted with round cairns, which are found in rows aligned towards the solstice sunrise/sunset. Rows of burial mounds are believed to have not only aligned to points in the landscape or sky, but also to have marked boundaries in the landscape between communities.

Certainly, social boundaries were important to Bronze Age people, and were made obvious in the landscape. A clear boundary, the Urra Moor Dyke, marks the crest of Urra Moor, east of Chop Gate. Dykes like this are covered in greater detail later within this chapter, but simply put: they are ditches dug to mark boundaries, often dated to the mid-Bronze Age (est. 1600–700 BC). Accessing the dyke is easy, as its length is followed by a footpath.

THE LORD STONES

NZ 52368 02980

Two small mounds can be seen poking up from an unkempt field in the west of Lord Stones Country Park, near the brow of Green Bank. Although they may appear unremarkable at first glance, these mounds are two of a total of four ‘round barrows’ on the hillside. Such earthen mounds, built to hold the remains of the dead, are a common sight throughout the national park, particularly along its outer edges. At least eight round barrows dot the uplands surrounding Green Bank, but those closest to the country park are the most visible and accessible of them all.

The barrow nearest the road is surrounded by kerb stones, which hold the mound in place. These are the eponymous Lord Stones, which lend their name to the adjacent visitors’ centre. The largest of these, known as the Three Lord Stone, is decorated with cup marks, concave depressions pecked into the surface of the rock. Cup marks typically date to the Neolithic and were likely created using stone or bone chisels.

Thousands of stone surfaces in the British Isles display cup markings, from natural crags to standing stones. Cup marks were common in northern England around the early to mid-Neolithic period (est. 3800–3000 BC), yet kerbed barrows like this were far more abundant in the Early Bronze Age (est. 2500 BC). Therefore, the rock art may have been reused from an earlier Neolithic site, possibly a natural boulder adorned with cup marks.

THE THREE LORD STONE AND THE DISTANT CRINGLE MOOR.

The tendency for Bronze Age people to build barrows on the uplands was largely a practical matter. Weather conditions were both wetter and warmer during this time, encouraging settlement on the uplands. At this time, there developed a tendency to build barrows on the crests of hillsides, where they would silhouette against the sky, appearing larger from below. However, the position of the Lord Stones is somewhat atypical, sitting in a dip between two hills, set back from the rest.

Author’s note: Although these barrows are located next to a footpath, it is important they are not disturbed. These are the final resting places of people who lived upwards of 4,500 years ago. They have endured the ravages of history only because of their isolation, which today poses them a greater risk. If you do decide to visit burial monuments like these, keep in mind that you should ideally admire from a short distance.

NAB RIDGE BRIDE STONES

SE 57565 97908

This is one of many prehistoric monuments in the North York Moors known as the ‘Bride Stones’, a bastardisation of the old Norse ‘brink stones’, meaning ‘stones near a crag’. Reachable by a footpath that winds its way east from Chop Gate’s village hall, the Bride Stones lie on a terrace near the edge of Nab Ridge. Though often misclassified as a stone circle, this site is, in truth, the remains of a burial mound. To the north, another round cairn survives, although it is overshadowed by a modern monument erected above it. To the north-west, down the hill, the scattered remains of a Bronze Age settlement are evident.

Twenty-seven stones form the circumference of the Bride Stones. In some areas, they are tightly arranged to create a neat ring of megaliths. Like the Lord Stones, they are kerb stones that once surrounded a mound. In England, kerb stones often disappeared first when barrows were cleared for ploughing. Yet, in this unusual case, only the rubble of the inner cairn was removed, without obvious reason.

Larger kerbed barrows like this often date to the Early Bronze Age (est. 2500 BC), built to accommodate single burials (as whole skeletons interred within cists). Not only would this example have been massive in its original form, but its prominent kerb stones suggest a fair amount of time and effort were put into its creation. Sadly, much of the site was destroyed during looting, and it so it remains unclear what, or who, was buried here.

NAB RIDGE BRIDE STONES FROM ABOVE.