Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

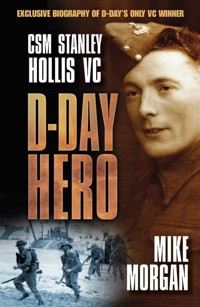

Stanley Hollis won the Victoria Cross when, on the 6th of June 1944, he single-handedly stormed a German pillbox before going on to save the lives of two comrades. D-Day's only Victoria Cross winner, Hollis was uniquely recommended for this coveted award twice on 6 June. A tough, working-class rebel, Hollis was no model soldier: he was forever being 'busted' to corporal for various misdeameanours, only to win his stripes back again. Few soldiers can have seen as much close combat action as Stanley Hollis. He fought with the Green Howards at Dunkirk, in the Western Desert, in Italy, on D-Day and through France and Germany to the end of the war. Seriously wounded and taken prisoner by the Afrika Korps, Hollis was personally congratulated by Rommel, then made a daring escape. In Italy, he was recommended for the Distinguished Conduct Medal and was later mentioned in despatches, going on to undertake a dangerous undercover reconnaissance of the Normandy invasion beaches. On 6 June 1944 Stanley Hollis was involved in two actions that led to his award. During the primary assault, Hollis single-handedly stormed a German pillbox, saving his company from certain injury and death and enabling them to open the main beach exit. Later that day he saved the lives of two comrades trapped by heavy gunfire in a collapsing house. Fully illustrated with archive photographs and ephemera, this unique biography of a little-known British Second World War hero shows the real man behind the heroic image. Mike Morgan has received the Hollis family's full co-operation and draws exclusively on personal diaries, letters and other memorabilia.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 306

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

This book is dedicated to my great friends Mick Brennan and Jack Paley – a Second World War comrade of my late father Jack Morgan of the elite SAS Intelligence wartime section – and the many generations of soldiers and officers of The Green Howards, one of Britain’s finest, most famous and historic regiments, and to its eighteen VC winners, including those dauntless fighting men from two world wars.

But it is principally dedicated to the regiment’s modest yet irrepressible D-Day hero – Company Sergeant Major Stanley Elton Hollis VC – without whom this story, one of the Overlord invasion’s most enduring tales of courage, leadership and triumph over the most testing of combat situations, could not have been written.

What happened in June 1944 was important to the whole world, and it is right that we should be reminded of the deeds of those who wore the badge of The Green Howards on that momentous day when the 6th and 7th Battalions waded ashore on Gold Beach.

A Soldier of The Green Howards Regiment

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Author’s Note

Foreword by Field Marshal Lord Inge

A Modern View of Heroes by General Sir Michael Walker

Campaign Map

Preface

Acknowledgements

Prologue: D-Day Cataclysm

One A Rebellious Yorkshire Upbringing

Two A Truly Indestructible Soldier

Three Storm of Retribution

Four A Fearless Fighting Legend

Five Stan’s Courage Inspired D-Day Victory

Six Suicide Attacks

Seven The Man They Couldn’t Kill

Eight Our Hero through the Years

Nine Stan’s Legend Lives On

Epilogue

Appendices

I Stan’s Official Citation

II A Short History of The Green Howards

III Gold Beach, Normandy, 6 June 1944 – Order of Battle

IV The Green Howards Second World War Medal Winners

V The Green Howards 6th Battalion Fighting Service during the Second World War

VI The Green Howards Normandy Roll of Honour

Bibliography

About the Author

Copyright

Author’s Note

This book was first written in 2004 and contains many comments from numerous individuals, Stan's old comrades, officials and family members. In the interim, some have changed titles or occupations and some have sadly died. I have made some of the more obvious updates and changes, but it has been impossible to trace every contributor, so I have left the remainder as they were known at the time of origination.

Statue memorial in memory of Stan

The proposed memorial is an exciting new development of the Stan Hollis VC story, recognised by generals, former field marshals and historians as one of the three finest VC awards of all time. This saw Stan and battle-hardened Green Howards at the forefront of the first wave on Gold Beach – hand picked for the job by Monty, the overall invasion commander. The fate of the invasion's British, American and Allied success rested on Stan's and his comrades' shoulders at this key point in history, likewise at the US first wave at bloody Omaha and Utah beaches. Many young men paid the ultimate price to ensure Allied victory.

There are now plans for a £130,000-plus monument to Britain's unique D-Day hero to be erected in 2014 near the Cenotaph at Linthorpe, in his home town of Middlesbrough. Plinths on the granite base will feature Stan's D-Day heroics, Dunkirk, a Regimental Green Howards badge, his North Africa campaign, VC details and other tributes, including one by the author (see p. vii).

A volunteer committee, headed by retired businessman Brian Bage of Guisborough, who knew Stan well when he had his North Ormesby Green Howard pub, has been fundraising hard to help the monument become a reality. Haverton Hill's Impetus Environmental Trust has pledged most of the grant funds and detailed plans drawn up by Middlesbrough Council's late principal architect Bernard Griffin, with full backing of the council, public, serving and former soldiers and well wishers countrywide via donations.

It's planned to include a bronze statue of Stan blazing away with his Sten gun while charging German pill boxes he captured single-handedly on D-Day, risking near-certain death. The Hollis family, including Stan's son Brian and daughter Pauline, solidly back the project and, once completed, it will be a fitting memorial to tell Stan's unique story well into the next century.

This also coincides with the 100th anniversary of the start of the First World War, with the fallen of two world wars and others commemorated on the nearby Cenotaph. A lecturn near Stan's memorial will include a proud list of eighteen local VC recipients, including Stan, from the Yorkshire Regiment (Green Howards), as well as the names of those who have prominently contributed to the memorial.

The following inscription will appear on the memorial once complete. One look at Stan's amazing VC citation, published in full in this book, confirms this man was special and will never be forgotten.

The author's memorial inscription will read:

The only serviceman to be awarded the Victoria Cross on D-Day, June 6, 1944, for his actions at Gold Beach, the Mont Fleury Battery and Crépon, during the Normandy invasion of Europe.

An immensely brave and modest family man born at Archibald Street, Middlesbrough on September 21, 1912

A never-to-be forgotten leader, protector and inspiration to his comrades.

Foreword

Field Marshal the Rt Hon. the Lord Inge KG, GCB, PC, DL, Colonel of The Green Howards 1982–94 and former Chief of the Defence Staff

The Victoria Cross is very rarely awarded. It is our country’s supreme award for gallantry in the face of the enemy. This book tells the story of Company Sergeant Major Stanley Hollis VC of The Green Howards, who was awarded the only Victoria Cross on D-Day during the Normandy Landings on 6 June 1944.

CSM Hollis was a legend in the 6th Battalion The Green Howards and saw active service at Dunkirk, in the Western Desert and Sicily. During the fierce fighting at Primosole Bridge in Sicily he had been recommended for a Distinguished Conduct Medal and had already been Mentioned in Despatches. Even in a battalion with a distinguished fighting record he stood out as a remarkable person and leader.

For his outstanding bravery on D-Day he was awarded the Victoria Cross for two very distinct acts of great courage, which the author Mike Morgan describes so well in this book.

I was fortunate enough to meet Stan Hollis, first as the landlord of The Green Howard public house in North Ormesby, Middlesbrough, but, more importantly, as one of the key guest ‘artists’ on the Army Staff College’s annual battlefield tour in Normandy. This battlefield tour took place every year from 1947 to 1979 and was the highlight of the year’s course. Its aim was to instruct the Staff College students about how men behaved and reacted in battle and under stress. Stan Hollis was one of the stars of the 50th (Tyne Tees) Division presentation along with his Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Colonel Robin Hastings DSO*, OBE, MC.

I was privileged to hear Stan Hollis’s inspirational tale as a student, later as a member of the Directing Staff of the Staff College and, finally, as Commandant of the Junior Division of the Staff College. I heard him tell his story in person seven times and then, after his death, a further three times on tape. I never failed to be moved by his account and he held the students – British, Commonwealth and foreign – in the palm of his hand. There is no doubt that he left a marked impact on many of the Army Staff College’s students. Indeed, in General Sir John Wilsey’s excellent book on Colonel H Jones, who won a posthumous Victoria Cross in the Falkland Islands, he comments on Stan Hollis’s impact on Colonel H as follows:

By the end of the tour vital lessons had been assimilated, some subliminally. First, that even the best-laid plans do not survive the first shot of battle. Next, the eventual outcome is largely determined by the initiative and the actions – or inactions – of individuals or groups. Third, in good units, the officers and senior non-commissioned officers always take a disproportionate share of the casualties.

The final lesson came directly from Hollis, although other speakers echoed it. When asked – as he always was – why he had undertaken such a seemingly suicidal assault on a German pillbox over open ground in broad daylight, he replied quietly and with humility: ‘Because I was a Green Howard.’ This was all that needed to be said. His audience understood at once that CSM Hollis’s instinctive loyalty to his regiment, and to those wearing his cap badge, meant that any lesser action would have been unthinkable at that moment. This was the esprit de corps, the most powerful ingredient of the regimental system which was, and still is, despite many recent changes, the cornerstone of the British Army.

In 1981 Mrs Hollis and her family decided that, for financial reasons, they had to sell Stan Hollis’s Victoria Cross and other medals. The Victoria Cross was sold for in excess of £30,000 which, at that time, was by far the highest price ever paid for a Victoria Cross, and it was a great sadness to The Green Howards that they were not able to raise enough money to buy it.

During my time as Colonel of The Green Howards I was keen to discover the name of the anonymous buyer of Stan’s Victoria Cross so that if he, or she, ever did decide to sell it, the regiment would be given the first option to buy it. I found out who it was by chance rather than by skilful detective work!

I had met Sir Ernest Harrison OBE, then Chairman of Racal Electronics plc, at a race meeting and later he and his wife, Janie, came to dine with us. It was at that dinner party that he told Letitia, my wife, the dramatic news that he was the anonymous buyer, not only of Stan Hollis’s VC, but also of Private Henry Tandey’s VC. Tandey was also a Green Howard and was the most highly decorated soldier of the First World War who had survived; he had been awarded the Victoria Cross, the Distinguished Conduct Medal, the Military Medal and had been five times Mentioned in Despatches. It was a staggering piece of news! However, even more wonderful news was to follow.

Sir Ernest became deeply involved in helping The Green Howards erect a memorial to the regiment’s achievements during the Second World War and it is not by chance that this outstanding war memorial is sited in Crépon, the village where Stanley Hollis carried out the second of his courageous acts on D-Day.

The final twist in this story is that at a dinner given in honour of Sir Ernest and his family, to thank them for their magnificent support for the Crépon Memorial, Sir Ernest made the wonderful announcement that he and his family had decided to give the medals of both Stanley Hollis and Henry Tandey to the regiment that very day. It was a most generous and wonderful gift.

Finally may I, on behalf of The Green Howards, thank and congratulate the author, Mike Morgan, whose own father, Corporal Jack Morgan, served with distinction in the 2nd Special Air Service Regiment during the Second World War, on capturing so succinctly the character of this very special man who means so much to my regiment.

A Modern View of Heroes

General Sir Michael Walker GCB, CMG, CBE, ADC Gen., former Chief of the Defence Staff

Two things stand out about Company Sergeant Major Stanley Hollis’s story. Firstly, the wider significance of what CSM Hollis and his men were doing on that day in June 1944 when he was awarded the VC, and secondly the significance of such a remarkable story on the armed forces of today.

CSM Stan Hollis belonged to D Company, 6th Battalion The Green Howards. As part of 69th Brigade, 50th (Northumbrian) Division, they were to land at King Sector of Gold Beach on the Normandy coast and create a foothold that would enable 100 divisions (the majority US) to be deployed on the continent for the final assault on Germany.

With 100 divisions waiting in the wings, it was imperative, at all costs, that CSM Hollis and his men were successful. It seemed likely therefore that during these initial landings some extraordinary acts of bravery were going to have to take place for the operation to be a success.

You will read from Mike Morgan’s account that D Company fought hard to achieve their mission at some significant loss among their own ranks. This sacrifice, along with such determination, initiative and personal courage, enabled a track exit from the beach to be opened at an early stage that had a direct bearing on the operation as a whole.

The modern-day battlefield has changed from that of CSM Hollis’s day – almost beyond recognition. Sophisticated intelligence-gathering techniques and the advent of precision-guided munitions result in an approach, in human terms, verging on the non-confrontational. Fewer and fewer people find themselves attacking trenches, assaulting machine-gun posts or, as in CSM Hollis’s case, rushing enemy pillboxes. But there is one thing we in the British armed forces have not lost sight of: in order to obtain meaningful results, we must always seek to achieve a foot on the ground. And often that foot on the ground is gained only through extraordinary individual acts of courage.

As I sit here writing, I have in front of me the most recent Operational Honours list. I am proud to say there are no fewer than one George Cross, twenty-six Military Crosses and thirteen Distinguished Flying Crosses (including two Bars to DFCs). In total 120 awards for gallantry have been made. The point is clear. The young men and women in our armed forces are as capable today of making such selfless acts of bravery as they were in CSM Hollis’s day. I believe they are able to do this because theirs is a provenance born out of a strong sense of duty, professionalism and desire not to let the team down. As CSM Stan Hollis rushed at his pillbox, winning his Victoria Cross, he unwittingly set a standard: a standard that was to live on for generations to learn from and aspire to.

CSM Stan Hollis’s actions remind us that it is not technology or mass that make an armed force so potent – it is that most valued asset: its people.

From a campaign map compiled by the late Captain W.A.T. Synge, supplied by The Green Howards Regimental Museum.

Preface

Company Sergeant Major Stan Hollis VC richly deserves his place among Britain’s greatest fighting heroes, not just because he was the only man to win the Victoria Cross on D-Day in such impressive fashion – being nominated for the award for two entirely separate actions – but because he consistently displayed the highest levels of gallantry in some of the most desperate front-line actions of the Second World War, despite being seriously wounded on five occasions.

His record, as related fully for the first time in this book, speaks for itself and puts him among the highest echelons of VC winners – alongside men like the Dam Busters hero Guy Gibson and a select handful of other supermen.

The difference between these legends and Hollis was that he was from the lower ranks, a real working-class hero from the tough districts of Teesside – a man who knew how to graft for a hard day’s living in the steelworks and a superb soldier in the self-same way.

Even his own highly decorated officers in the 6th Battalion The Green Howards said without exaggeration that his exploits in Normandy were worthy of two or even three VCs. As stated, he was recommended twice for the VC on D-Day on separate occasions, but could only be awarded one medal for a single day’s action. He was also recommended for the Distinguished Conduct Medal and Mentioned in Despatches for his part in the bloody hand-to-hand fights which followed the seaborne invasion of Sicily, the precursor of Overlord, the largest invasion the world has ever seen. Much was learned in the Sicilian operation which later enabled the successful invasion of Occupied Europe and the eventual destruction of Hitler’s Nazi empire.

Hollis was a fighting soldier in the truest sense of the word – tough as nails, a muscular 6 foot 2 powerhouse of a man with fiery red hair and huge hands like shovels. His lethal handling of any sort of small-arms weapon, grenades or bombs, was legendary and his reactions in a firefight were like lightning, with an instinctive decisiveness and speed of thought and action which invariably led to the annihilation of the opposition – even when the odds were stacked highly against success, or even survival. But more than 100 enemy soldiers had already fallen to Hollis’s gun from Dunkirk in 1940 to the battle of the bocage, in Normandy, in 1944, including more than ten on D-Day alone.

Hollis had a volcanic temper, if provoked, and was quick to use his fists if needed, no matter whether in the midst of a full-scale close quarter attack or in a fracas with other British troops behind his own lines, or back home on leave. In action, he was a superbly disciplined soldier who rose from the ranks to become a highly respected sergeant major of the 6th Green Howards, who inspired hundreds of his fellow soldiers with his selfless courage. He possessed an unbreakable force of will, which meant that he could also at times be deliberately wayward and rebellious away from the battlefront.

CSM Hollis was a naturally modest man, who shunned publicity or, at most, gave journalists a mere sentence or two to quote when asked about his famous fighting record. However, in this book for the first time several thousand words are published from his own first-hand memories of his D-Day exploits, gleaned from an extremely rare tape made on a trip to France, when he described to young officers in detail a start-to-finish account of how he won his country’s highest honour.

Many people already believe that Hollis fully deserves a fame which will never be forgotten, especially when D-Day commemorations come around, such as the seventieth anniversary of Overlord and beyond, way into the future, in fact.

But of all the superb soldiers, airmen and sailors who have won Britain’s highest honour for valour, as his true story so vividly shows, there is no other VC winner quite like CSM Hollis.

Acknowledgements

First of all, I would sincerely like to thank Field Marshal Lord Inge, the last ever Field Marshal in the British Army and Chief of the Defence Staff 1994–7, for his illuminating and very personal foreword to this book. No one could have expressed the essence of Stan Hollis’s character more skilfully or captured the deep affection and admiration in which he was held by his comrades and superior officers alike.

I am also deeply grateful for ‘A Modern View of Heroes’, by the former Chief of the Defence Staff, General Sir Michael Walker, which clearly shows that bravery of the Hollis variety still has a place in the British Army of the twenty-first century despite the ongoing march of weapon technology.

For vital behind-the-scenes help, Major Roger Chapman, former curator of The Green Howards Regimental Museum at Richmond, and his staff have generously opened up the historical archives of the regiment to me, giving their invaluable professional help and guidance. They have provided superb drawings, photos, accounts and information, which have given an unmatched authenticity to this book, the first authorised biography of CSM Hollis to be written. I am most grateful to one and all, but especially to Major Chapman for his patience, knowledge and good humour over the entire research and writing phase of this book.

My sincere thanks also go to Stan Hollis’s son Brian and daughter Pauline, who have both provided many rare photographs, accounts and memories of their father, the majority of which have never been published before. Their contribution has been crucial and is especially appreciated.

I am grateful too to my former boss Steve Dyson, editor of the Middlesbrough Evening Gazette, for whom I worked at Guisborough as a senior district reporter, for allowing me full access to the photographic and editorial records of Teesside’s oldest and leading newspaper, part of the Trinity Mirror Group. Also to former chief librarian Barbara Thompson, for her skill in enabling me to access this wealth of information, together with colleague Paul Delplanque, who has also been most generous in sharing his expert knowledge of British naval fighting ships, which has been much appreciated in connection with the D-Day landings.

I also warmly acknowledge the superb close-up cover photos of Stan Hollis’s VC taken by photographer Ian Cooper, by kind permission of The Green Howards Regimental Museum, Richmond.

I am also very grateful to my wife Penny and daughters Katie, Laura and Jennifer, who have all helped and encouraged me in many ways as this book has progressed and to all the many individuals who have provided information, photos and some marvellous eyewitness memories of CSM Hollis.

Lastly, I would like to record that I am honoured indeed to have had the chance to write the exclusive biography of one of Britain’s greatest military heroes – one of the toughest, most self-effacing and most down-to-earth soldiers who ever lived.

Whenever the words D-Day are spoken, or written about, so too are the exploits of Stan Hollis of the 6th Battalion, The Green Howards, for the stupendous courage and leadership he showed that day. There is no finer, or more lasting, tribute to a great character and a great soldier.

PROLOGUE

D-Day Cataclysm

The violence, speed and power of our initial assault must carry every-thing before it.

General Bernard Law Montgomery, the Allied Invasion Land Commander

Wherever the fighting was heaviest throughout the day, Hollis displayed daring and gallantry … he alone prevented the enemy from holding up the advance of The Green Howards at critical stages. … By his own bravery he saved the lives of many of his men.

From the VC citation of CSM Stan Hollis

D-Day was dubbed Deliverance Day by the British and American war leaders Churchill and Roosevelt to symbolise the liberation of a Europe ensnared under the iron Nazi yoke of terror for four bitter years.

As the clock ticked down to zero hour, at precisely 7.30 a.m., 6 June 1944, an awe-inspiring cataclysm without equal in military history was about to be unleashed at Gold Beach, Normandy, a lynchpin of the three main British and Canadian beachheads. Although he did not yet know it, just one man among the Allied invaders who would strike the first blow would win the highest honour for valour which Britain can bestow this day – Company Sergeant Major Stanley Elton Hollis, of D Company, 6th Battalion The Green Howards.

And, as the records show, he was recommended not once for the VC during the first few hours of this Anglo-American-Canadian quest to liberate Europe, but twice, in separate hair-raising actions which displayed courage well beyond the call of duty.

The biggest, most complex and in many ways most risky invasion that the world has ever seen, or is ever likely to see, was about to explode into violent action on the beaches of Normandy. Meanwhile, as the huge Allied fleet approached France, Hollis and his young British comrades waited aboard their assault ship just off the coast, checked their weapons and equipment and prayed for the action to get under way to break the near-unbearable tension.

Their vital mission was to be the first Allied troops ashore on D-Day to neutralise the heavy guns of the Mont Fleury battery, sited in a commanding position on higher ground just beyond the beachhead. Intelligence sources indicated four well-protected fortified casemates, each containing 122mm guns, supported by a mobile battery of four 100mm guns. Another concrete emplacement at La Rivière housed an 88mm gun and other casemated 50mm guns. This powerful 88mm weapon was well protected by thick concrete defences from shell fire from the sea, but was designed to pour fire at right angles to the coast – in effect right along Gold Beach, where The Green Howards and supporting tank units of the 4th/7th Dragoon Guards and elements of the 79th Armoured Division were about to forge ashore. There was a further 50mm gun in an open casement at Mont Fleury lighthouse and, further inland near the village of Crépon, there was another mobile battery of 100mm guns in open emplacements. These strongpoints were well protected by minefields, numerous machine-guns and well-armed and camouflaged infantry positions. All, naturally, were prime targets for the first wave attackers of The Green Howards, who had trained meticulously for their task using hundreds of photographs and models and realistic rehearsals so that they each intimately knew and could recognise without hesitation every landmark and feature of the vital King Sector of Gold Beach, where they would be the first invasion troops ashore.

German defenders of the 716th Division, supposing themselves safe and secure in their concrete pillboxes, trenches and steel-reinforced gun emplacements all along the Normandy coast, were still totally unaware of the overwhelming force which was rapidly approaching in the early morning mist, waiting to destroy them, just out of sight over the horizon.

This unprecedented invasion fleet massed in the English Channel involved an immense armada of nearly 7,000 ships, 250,000 soldiers and sailors and a protective aerial umbrella flying in the skies overhead of 3,000 of the latest combat planes – fighters, rocket-firing fighter bombers and heavy bombers.

British and American battleships would soon bombard enemy positions and key sites more than 20 miles inland of the invasion beaches, and bombers would further soften up numerous pre-ordained enemy targets. The British First World War veteran battleship Warspite was one of those dreadnoughts which would unleash the immense power of her eight 15-inch guns on targets which her crew could not see, yet could hit with devastating effect using sophisticated radar and range finders. Many cruisers and destroyers would also soon join in the bombardment closer to the shore – striking at many of the strongpoints on and behind the Gold Beach area.

Cruisers included the redoubtable HMS Orion, which was to register no fewer than twelve direct hits on the Mont Fleury battery behind King Sector in an amazing display of good shooting. HMS Belfast, which still survives to this day as a wartime attraction to the public moored in the River Thames in London, also did much solid work with her 6-inch guns. Other cruisers operating close inshore off Gold Beach included Ajax – one of the three cruiser conquerors of the scuttled pocket battleship Graf Spee at the Battle of the River Plate in 1939 – plus Argonaut, Emerald and Flores.

Hunt class destroyers Cattistock, Pytchley, Cottismore and Krakowiak and fleet destroyers Ulysses, Urania, Jervis, Grenville, Ursa, Ulster, Undaunted, Urchin and Undine also brought every gun they possessed to bear on the enemy positions throughout the Gold Beach area. However, the crucial knockout blow would be delivered by the elite infantrymen of The Green Howards, their accompanying armour and the follow-up forces who had to storm ashore through withering machine-gun, artillery and mortar fire. British and Allied commanders had already defeated the cream of the Axis forces at the history-making battle of El Alamein in North Africa, in Sicily, parts of Italy and in other theatres of war. But they knew that to beat Hitler and his still formidable Nazi forces they had to fight and defeat the enemy on their home ground – in Occupied France, the Low Countries and finally in the heartland of Germany itself.

The invasion land commander, General Montgomery, legendary victor of El Alamein, had hand-picked the battle-hardened 50th Northumbrian Division to lead the momentous invasion at Gold Beach, and the 6th/7th Green Howards were to land the initial knockout punch. High casualties were predicted.

Montgomery knew from commanding this potent force in previous tough battles won in North Africa and Sicily that these troops were among the very finest that Britain and her allies possessed, and so he entrusted them with this most vital of missions with utmost confidence. The men of the 6th and 7th Green Howards Battalions were to be the key initial spearhead on Gold Beach. It was an extremely hazardous honour and the men were told that up to 70 per cent casualties could be suffered. There was even a distinct possibility of annihilation by the well-dug-in defenders and their cunningly hidden machine-guns, minefields and artillery.

The German commander in this vital spearhead sector, General Major Wilhelm Richter, had deployed behind Gold Beach the 441st East Battalion, which included Russian volunteer auxiliaries and elements of the 726th Regiment. In support, the guns of the 352nd Artillery Regiment covered the beach. The Germans had not had time to install all of these artillery pieces, but still had more than enough in position to wreak widespread devastation. The British invaders, meanwhile, had no knowledge of these developments from their latest intelligence reports.

Lurking inland, less than an hour’s drive away, were the very powerful and well-equipped armoured columns of the 21st Panzer Division, the prime counter-attacking force designed to repel any invasion in Normandy or the adjoining areas. This force was supported by the elite Panzer Lehr Division and the 12th SS Panzer Division (Hitlerjugend). These 10,000 diehard Hitler Youth fanatics would soon be virtually wiped out in their desperate attempts to stem the Allied breakout of Normandy, but more of this later.

CSM Stanley Elton Hollis, of 6th Green Howards assault company, who was in the vanguard of the very first wave, was at this precise moment in history heading, along with 500 well-armed comrades, towards the heavily defended Normandy shores. He was packed in tightly with his men inside a bucking and heaving landing craft along with their bulky equipment. Hollis was just one soldier in hundreds of thousands who would fight for his life this momentous day. Many would not live to see the end of it on both sides, including scores of these young and bold Green Howards attackers.

Hollis Killed More than One Hundred

CSM Hollis had already killed more than ninety enemy soldiers single-handedly during an action-packed war stretching back to the miracle escape of the British Army at Dunkirk in 1940. Here he had had to swim virtually naked, wounded and exhausted many yards from the beaches to a waiting navy vessel, where he was plucked to safety by stalwarts of the Royal Navy. He was later to say that he escaped literally by the skin of his teeth. He also saw exceptional service in Sicily, at Primosole Bridge, in July 1943, where he was again wounded and recommended for the Distinguished Conduct Medal. He was also prominent at the great victory at El Alamein in North Africa in October/November 1942, which routed Rommel’s famed Afrika Korps.

The formidable Hollis was, at 31 years of age, a veteran of near unmatched experience and resolve. By the time D-Day was over, Hollis’s personal score of enemy killed would be more than a hundred and he would win Britain’s highest honour, the Victoria Cross (VC), for two stupendous feats of courage, widely recognised as some of the most daring in the history of the VC. But this tally of enemies eliminated was not a sadistic ‘cricket score’ to the ultra-reliable, model professional soldier Hollis had become over years of dedicated service. It was merely a fact of life for a true combat soldier, a reflection of a grim battle for personal survival in a conflict which had lasted in his case for four long years. During this time, all spent with the 6th Battalion The Green Howards, Hollis had consistently exhibited an instinctive and iron-willed determination to protect his men’s lives at all costs, often putting his own life on the line in the process. This was precisely the sort of selfless valour he would show once again on D-Day in such unforgettable fashion, as he describes so vividly in his own words for the first time in a later chapter of this book.

In the safe and sanitised confines of the twenty-first century it is sometimes hard to grasp what a brutal and frightening experience war – total war – is and there is unlikely ever to be another land war, or seaborne invasion, of the immense magnitude of D-Day, now known the world over in history by its codename, Overlord. Every officer and soldier in this vital Green Howards spearhead attack was under no illusion that this D-Day assault was going to subject them to war in all its most terrifying forms. The old hands knew it would be similar in many ways to the horrors of going ‘over the top’ in the trench warfare of the First World War, as Hollis’s father Alfred had as a young Tommy in the Yorkshire Regiment in the trenches nearly three decades before. He had survived, though he was badly gassed and his health impaired as a result. Hollis, meanwhile, was convinced by a powerful premonition, experienced as he crossed the Channel and headed towards the Normandy coast, that he too would survive the ordeals of this D-Day mission no matter what transpired. He was determined to return to his pretty young wife Alice and his children Brian and Pauline back in Britain.

Survival Was the Keyword

Winning objectives and destroying the enemy in close combat in the Second World War was a necessary fact of life in front line action for these young Green Howards as it had been in countless wars past, for any soldier who wanted to stay alive for any length of time. It was precisely because Hollis had already seen far more hand-to-hand fighting than most in this war that he was absolutely determined to overcome this last great hurdle. But like many, he did not want to be a dead hero. Everyone sensed the historic magnitude of the task, but knew that the risks and opposition would be great. Hollis knew that this D-Day mission to take the Mont Fleury battery, the Meuvaines ridge and the fortified village of Crépon would be a severe test for even his battalion of Yorkshire stalwarts.

Stan Hollis was a man of few words throughout his life. He never exaggerated or embellished anything he said or did. As he modestly told his daughter Pauline many years after the war when she asked about his D-Day exploits: ‘I was no hero – I did what I had to do. I just wanted to come home and survive.’

However, thoughts of loved ones had to be swiftly put out of the minds of the Green Howards attackers as they were given the invasion order to ‘go’ and clambered swiftly down the wet, greasy, specially webbed nets from the Empire Lance mother ship moored off the Normandy coast into the viciously rising and falling landing craft below. The sea was very rough and choppy this 6 June morning and many of the men were violently seasick. The hard, slippery ropes cut into the hands of the soldiers as they clambered awkwardly down into the grey, metal, oblong craft, with the steel ramp at the bows and the coxswain ensconced in an armour-plated protected compartment at the rear.

Getting into the landing craft was a challenge for the heavily loaded Green Howards assault troops, weighed down as they all were with rifles, grenades, Bren and Sten guns, mortars, packs, ammunition and medical supplies. Some rated it worse than facing the enemy’s bullets and bombs. In addition, many soldiers were carrying extra ammunition to dump at the shoreline for the following troops to use as they came ashore in their wake. One false move now could result in a soldier falling between the two grating vessels and the damage inflicted on a human body in those circumstances did not bear thinking about.

The troops, a blend of seasoned veterans of North Africa and Sicily, like Hollis, and well-trained but unblooded new recruits, clambered gingerly down, twenty at a time, into their allotted craft. There was little cheery banter, more a grim awareness of the dangerous trials that lay ahead. They all knew from scores of detailed planning briefings in the run-up to the invasion exactly what and where their targets were and what risks lurked unseen ashore. But as always, the fear of the unknown gnawed at many stomachs before the adrenaline rush of combat drove those negative demons to the back of their minds.