7,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Amber Books Ltd

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

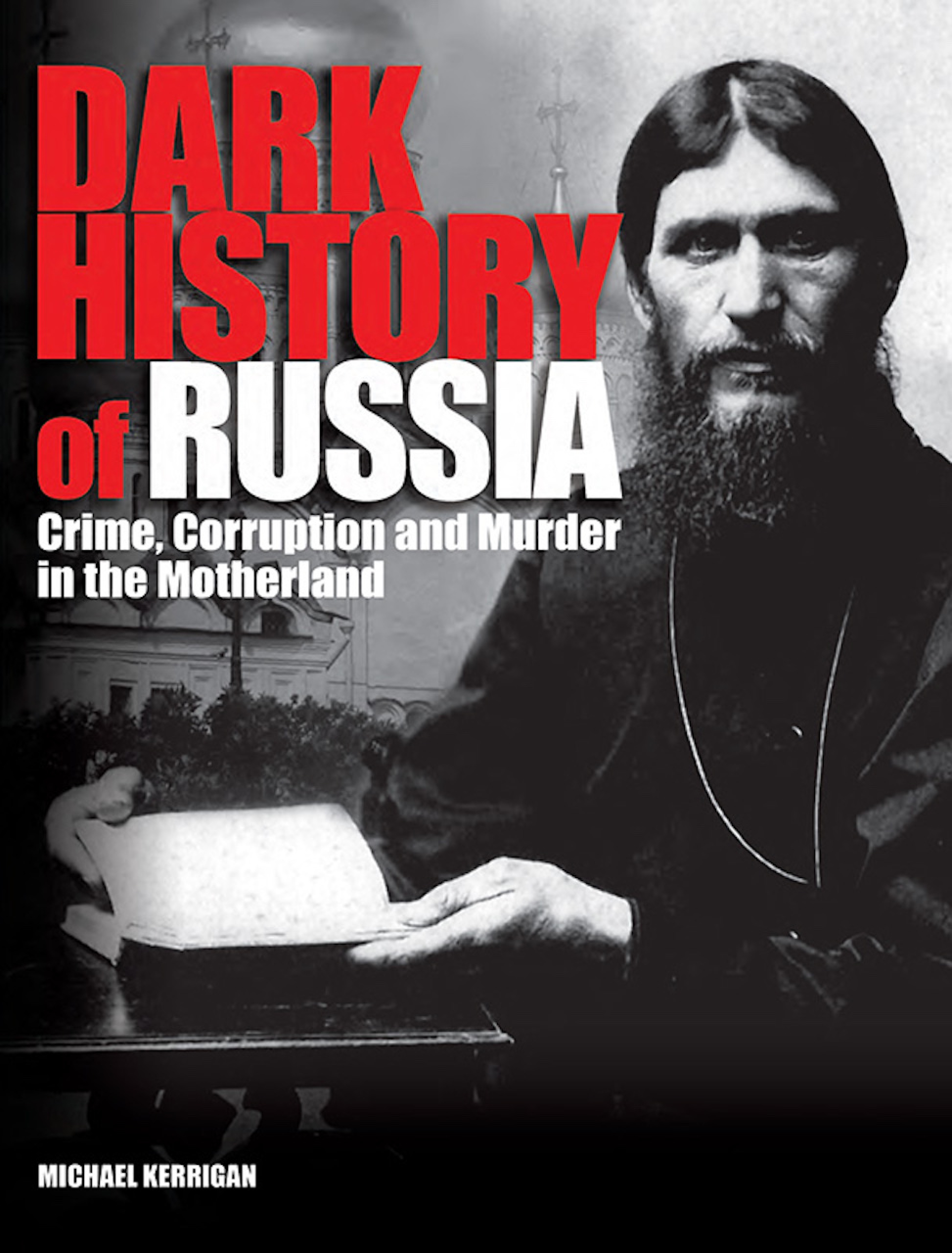

From monarchy to the world’s first socialist state, from Communism to Capitalism, from mass poverty to Europe’s new super rich, Russia has seen immense revolutions in just the past century, including purges, poisonings, famines, assassinations and massacres. In that time, it has also endured civil war, world war and the Cold War. But the extremes of Russian history are not restricted to the past 100 years. When Napoleon invaded in 1812, the Russians retreated, slashing and burning their own country and Moscow itself, rather than conceding defeat to Napoleon. They were victorious, but at immense cost. Russia’s history is also spiked with mystery. Did Stalin shoot his wife? Who ordered the killing of Rasputin? Or the shooting of Anna Politkovskaya and the poisoning of Alexander Litvinenko or the Skripals in Salisbury, England? What involvement and influence did Russian intelligence have on the 2016 US Election? In addition, it is a history of appalling disasters, such as at the Chernobyl nuclear power station and the sinking of the Kursk submarine. Ranging from medieval Kievan Rus to Vladimir Putin, Dark History of Russia explores the murder, brutality, genocide, insanity and skulduggery in the efforts to seize, and then maintain, power in the Slav heartland. Illustrated with 180 colour and black-&-white photographs and artworks, Dark History of Russia is a fascinating, lively and wide-ranging story from the Mongol invasions to the present day.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 272

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

DARK HISTORY OF RUSSIA

Crime, Corruption and Murder in the Motherland

MICHAEL KERRIGAN

Other related titles include:

Stalin by Michael Kerrigan

Dark History of the American Presidents

by Michael Kerrigan

Website: www.amberbooks.co.uk

Instagram: amberbooksltd

Facebook: amberbooks

Twitter: @amberbooks

First published in 2018

This digital edition first published in 2019

Published by

Amber Books Ltd

United House

North Road

London N7 9DP

United Kingdom

Website: www.amberbooks.co.uk

Instagram: amberbooksltd

Facebook: amberbooks

Twitter: @amberbooks

Copyright © 2019 Amber Books Ltd

ISBN: 978-1-78274-810-6

All rights reserved. With the exception of quoting brief passages for the purpose of review no part of this publication may be reproduced without prior written permission from the publisher. The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. All recommendations are made without any guarantee on the part of the author or publisher, who also disclaim any liability incurred in connection with the use of this data or specific details.

Contents

Introduction

1. ‘The Expanses are so Great...’: Kievan Rus

2. Life, Death and Tyranny

3. ‘I Write on Human Skin...’

4. Time and Patience

5. Something Better?

6. Tempering the Steel

7. ‘A War of Extermination’

8. Drowning in Falsehood

9. ‘We Will Bury You’

10. Opening Up and Closing Down

11. The Bear is Back

Bibliography

Index

Lenin’s Communists were ‘red’ in acknowledgement of the sacrifices made by previous revolutionaries – but the whole of Russian history has been soaked in blood.

INTRODUCTION

NOTES FROM UNDERGROUND

Violence, death and darkness have been built into the very foundations of the Russian state, the only real constant of two millennia of history.

GAGGING, gasping for breath through the scrunched-up fabric stuffing his frantic mouth, the little boy could no more speak than he could move. Tightly trussed with cord, a sobbing, shuddering, quivering bundle, he lay in the same foetal tuck that he had assumed in his mother’s womb a few short years before.

The village community, gathered around, looked on with awed respect, but no sympathy. The boy’s mother had been a foreigner – a slave – and the gods’ work was being done. As the priest pulled harder on the garrotting leash and the victim’s life struggle subsided, the prevailing mood was of an obligation met, of an auspicious start. With a gravelly slither and a muffled thud, the inert body fell into the deep pit before them. The men stood braced: now they could get to work raising the roof-post around which the new house would be built.

Later, anthropologists might choose to see their work as symbolic, this human sacrifice a spiritual acknowledgement of the roof-post’s central role as an axis mundi – an ‘axis of the world’. Connecting the three realms – this earth, the underworld, and the heavens above – it would represent the overall harmony of the universe in which they dwelt. Less reflective, perhaps, and certainly less articulate in the language of 21st-century scholarship, the early Slavs knew that what they had done was fitting. The gods required this offering in return for their favour. If the gods were to watch over this house, they were entitled to a sacrifice.

UP FROM BELOW

‘Every man has reminiscences which he would not tell to everyone, but only to his friends,’ remarks the narrator in Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s novella Notes from Underground (1864). ‘He has other matters in his mind which he would not reveal even to his friends, but only to himself, and that in secret. But there are other things which a man is afraid to tell even to himself...’

What goes for men appears to go for nations too. The collective reminiscence, that is history, tends to be a more or less upbeat narrative – but darker episodes refuse to be suppressed. The Russian story stands apart, however, in being shot through with tragedy and violence at nearly every stage of its existence. This, it seems, is a country whose whole history has been ‘dark’. By no means short of achievements, dramatic victories and great personalities, it has been by turns bleak and blood-sodden, tragic and grotesque.

At its best, the history of Russia has been characterized by cruelty and ruthlessness. Ivan the Terrible took the tyrannical violence of an absolute monarchy to its most monstrous lengths. Although in their different ways both worthy of the honorific, the two ‘great’ Czars, Peter I and Catherine II, were living caricatures, embodying the excesses of untrammelled authority.

Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s was a gloomy muse but a deeply illuminating one. No writer has shown more insight into the darker corners of the Russian consciousness.

Whether under czars or communist officials, Russia was to prosper in oppression. In its imperial splendour, it was carried by the cruelly exploited serfs. The depth of their servitude was arguably equalled, the sadism of their treatment almost certainly surpassed by the punishments dealt out to those deemed hostile to the dictatorship of Stalin from the 1920s on. With the most generous possible assessment, the achievements of communism were secured at an appalling human cost: some would insist that the Soviet experiment was anti-human by its nature.

Ivan the Terrible holds up the Orthodox Christian cross under which he (at least nominally) fought.

HUMAN SACRIFICE

Russia’s greatest historic triumphs have been attained in the sort of adversity that calls into question the victory that was secured. It was a self-destructive heroism that saw off French invaders in 1812 and Hitler’s German army in what Russians came to call the ‘Great Patriotic War’.

The country was self-destructive not just literally – in the burning of Moscow and the starvation endured by the citizens of Leningrad – but spiritually as well. Some sort of scorched earth of the soul enabled the Russian people to prevail by soaking up more suffering than their attackers could ultimately inflict; their subsequent celebrations were also times of deepest mourning.

Why should this be? Does Russian history labour under some kind of curse? Many Russians have felt this way down the generations. Rational analysis would hardly be expected to uphold such a conclusion. At the same time, though, where there has been so long and harrowing a history of suffering, the idea has acquired a certain mythic force.

HEALTH WARNING

If Russia’s history has been written in blood, it has also been written in a spirit of profound partisanship. For much of modernity, the country has been seen as menacing the West. It is generally accepted now, for example, that successive US administrations of the Cold War era talked up the Soviet nuclear threat. (They didn’t make it up, but they massively exaggerated Russia’s military power and reach.) Western politicians and media were never slow to criticize Russian policy, at home or in the wider world, or to attack the USSR’s disdain for human rights. Left-wing commentators pointed out that those same politicians and media were not half so perturbed when comparable attitudes were shown and equivalent crimes committed by US clients.

They were right: as ‘free’ as the Western media might have been, a certain collectivity of interests and assumptions assisted in what the linguist and peace campaigner Noam Chomsky called the ‘manufacture of consent’. Without the White House, Downing Street, the Élysée Palace or anyone else cracking the censor’s whip, the Western media more or less fell into line with the view coming out of these centres of Western power.

A clean-cut commissar wags a warning finger at a top-hatted, plutocratic-looking United States: he should reconsider his race to nuclear arms, or face the consequences… (1948).

COLD WAR RENEWED?

To some degree, the same stance has been true in the post-Communist period, certainly since the onset of what some call ‘Cold War II’. It has been said that the collapse of the Western banking system in 2008 emboldened Vladimir Putin’s Russia, encouraging it to rise above its own economic difficulties and start throwing its global weight around again. It can hardly be disputed that Russia has re-emerged as a mover and shaker on the world stage – although, in fairness, this was to have been expected once the turbulence following the collapse of communism had been weathered.

Up to a point, moreover, this is also justifiable: Russia has its own regional interests around the Black Sea, in the Caucasus and the Middle East. Why wouldn’t it want to defend them? As in Cold War I, the question comes down to how far we think Russia seeks to go beyond its own legitimate, immediate security interests to interfere in the affairs of the wider world. As in Cold War I, we have seen signs of journalistic attitudes towards Russia increasingly divided between hawkish hostility and ‘dove’-ish sympathy. It can be hard to know which view is right. To make matters more complicated, these divisions have not necessarily occurred along the left–right ideological lines that prevailed before.

DEMOCRATIC DEFICIT

If Western commentary on Russia should often be taken with a grain of salt, Russia’s rulers have historically lied freely. Nor have they had any truck with those ideas of official accountability and press freedom that Western governments have espoused (theoretically, at least). Under Communism, indeed, information management was weaponized. In the face of the world’s hostility, officials felt justified in deploying propaganda in the pretence that it was news.

But then, the USSR barely made the most minimal pretence of democratic freedom. The workers around whose efforts and requirements the whole society had supposedly been organized did not have the right to unionize, own their homes or travel freely, and were generally much less materially well-off than their ‘oppressed’ and ‘exploited’ brothers and sisters in capitalist countries. Political dissent was not tolerated; nor was any expression of opinion outside the institutions of the state. Critics of the Soviet order could be harassed – or, of course, sent off to labour camps.

Russia was as badly hit as anywhere by the financial crisis of 2008–9, though it was able to exploit ensuing global problems to its own ends.

‘Death to the World Imperialist Monster’: Soviet workers fight the forces of capitalist exploitation in this spectacular poster by Dmitry Moor (1883–1946).

Despite the use of worthy-sounding terminology (the word soviet itself denoted an elected workplace council; the Supreme Soviet or Congress was ostensibly their collective voice), the absence of any real opposition meant that the Communist Party’s ruling committee, the Politburo, exercised a degree of control over the country that the Czars could only have envied. A former lieutenant colonel of the Soviet Secret Police, the KGB, Vladimir Putin, Russia’s premier throughout the present century, has not shown himself to be especially invested in either press freedom or political plurality.

THESE SYSTEMS WERE ANYTHING BUT EGALITARIAN, BUT THEY DISHED OUT THEIR UNFAIRNESS MORE EQUITABLY THAN THE RUSSIAN CZARIST SYSTEM.

ABSOLUTE POWER

If we look for continuities between the Communist and the Czarist eras, we can most convincingly find it in the tendency of those with power to wield it absolutely. If there has been a curse upon Russian history, it has been that seemingly deep-seated instinct in those in charge that opposition was not to be tolerated. The notorious gulags of the Communist era carried on the work of the katorga camps to which criminals and dissidents had been sent since the 17th century. This was in its turn the consequence of structural problems in the polity as a whole. Historically, Russia had been held back by the weakness of any but the highest, most overarching, offices of state and the lack of an intermediate tier between the central authority and the masses.

Over the centuries, Western European societies had been building complexity, accumulating ‘squirearchies’ – influential lobbies of substantial farmers, rural professions, entrepreneurs and middle-class elites in the smaller towns and larger cities. Their demands, and their defence of their interests, acted to some extent as an inhibition on the freedom of action of the great landowners and the monarchies above them. These systems were anything but egalitarian, but they dished out their unfairness more equitably than the Russian Czarist system did.

Camp inmates labour to construct the North Pechora Railway in the Komi region of Arctic Siberia: thousands were to die in unspeakable conditions on such schemes.

FROM THE HOUSE OF THE DEAD

‘Where are the primary causes on which I am to build?’ asked Dostoyevsky’s narrator in Notes from Underground. ‘Where are my foundations? Where am I to get them from?’ In pagan times, Slavic custom demanded that a human sacrifice be offered at the start of any major construction; that a slave – often a child – be immured within the wall or floor of a new house. Towards the end of the first millennium, the Orthodox Church explicitly forbade this practice in its Nomocanon (Canon Law): ‘May he who places a human being be punished with twelve years of penitence and three hundred genuflections. Let a wild boar, bull or goat be placed instead.’

But the memory was to endure – as, apparently, was the practice; the folklorist Mikhail I. Popov (1742–90) recorded it well into the 18th century. Dostoyevsky surely recalled this in his creation of a strange and sinister speaking voice from beneath the floorboards – a voice that, in its self-degrading eloquence, seems to speak for Russia too. The house of Russian history was, it seems, all but literally founded on human sacrifice; the bodies of the dead are built into its very fabric.

This book will not attempt to argue that Russia is an accursed country, nor that its people have been collectively condemned to suffering by some centuries-old pathology. But the most dispassionate perspective on Russia’s past can hardly ignore the violence and turbulence, the chronic cruelty and suffering that seem to have dogged its history more or less throughout.

THE SUNGHIR SACRIFICE

SOME OF THE FIRST Russians we know of seem to have been ritually slaughtered. The bodies of a boy and girl unearthed by archaeologists at Sunghir, some 193km (120 miles) east of Moscow, brought with them their own notes from underground.

The two children, seemingly sacrificed some 30,000 years ago in the Upper Paleolithic period, had been placed head to head beside two adult corpses. Both victims had been physically disabled: the boy a dwarf, the girl’s skeleton showing shortened and bent thighbones. Their differences seem to have marked them out for sacrifice.

We should not conclude that they were social rejects, however. Archaeologists point out that their ‘abnormal’ features may have given them an exalted status. The more important the person, the more significant was the sacrifice. This would tally with the treatment of their bones with red ochre, made of clay, and the sewing of some 5000 ivory beads into their leather caps and clothes. They also had ornaments of Arctic fox teeth and pendants of semi-precious stones, along with exquisitely carved ivory pins: they certainly had not been casually thrown away.

Anthropological reconstruction has allowed us to see the Sunghir Children’s faces.

Rurik and his successor Oleg were effectively the founders of the Russian state. They are commemorated by this memorial in Staraya Ladoga, north of Volkhov.

1

‘THE EXPANSES ARE SO GREAT…’: KIEVAN RUS

Russia has always seemed very dark and disorientating in proportion to its vastness – as much to its own people, it seems, as to outsiders.

‘GREAT HATRED, little room, maimed us at the start.’ This straightforward explanation of his native Ireland’s wretched history offered by the poet W.B. Yeats (1865–1939) could serve for many other countries. Time and again, a sense of claustrophobia seems to have intensified ethnic and religious rivalries in societies around the world. Russia, however, has never had that problem.

AN AGORAPHOBIC AGONY

Russia has long been, by some distance, the world’s biggest country geographically, and that literal sense of spatial confinement would never have been felt. A character in Nikolai Gogol’s (1809–52) famous play The Government Inspector (1836) says of the small provincial town in which the scene is set: ‘Even if you ride for three years you won’t come to any other country.’

This is an impressive claim, but unsettling in its implications. How can a country so big and so comparatively empty provide anything in the way of a real ‘home’? How could anyone find a psychological anchorage in this all but endless space? Anton Chekhov (1860–1904), another Russian writer – and a practicing doctor too – diagnosed the vastness of his country as an important influence on its people’s mental health. ‘In Western Europe people perish from the congestion and stifling closeness,’ he wrote in a letter to a friend (5 February 1888), ‘but with us it is from the spaciousness. The expanses are so great that the little man hasn’t the resources to orientate himself…This is what I think about Russian suicides.’

A group of hikers make their way across a slope in Central Asia’s Saylyugem Mountains. The Russian landscape is mesmerizing in its sheer vastness.

At more than three times the global average, Russia’s suicide rate continues to shock, but psychologists haven’t generally agreed with Chekhov’s theory. At a more poetic level, however, it has the ring of truth. A sense of disorientation might always have been intrinsic to the Russian consciousness. The only country coalesced slowly out of what had been more or less empty and frontierless space. Where Western Europe’s countries are often clearly demarcated by natural features – rivers, mountain ranges or switches in landscape type – no such natural frontiers fence in the vastness of the Eurasian Steppe. Often described as a ‘sea of grass’, this semi-arid plain extends over 8000km (5000 miles) between Manchuria’s Pacific coast and the Hungarian plain (Puszta) in the west.

HOW CAN A COUNTRY SO BIG AND SO COMPARATIVELY EMPTY PROVIDE ANYTHING IN THE WAY OF A REAL ‘HOME?

PASTORAL VALUES

It was not only Russia’s physical but its human geography that seemed so open, indefinite, fluid and amorphous. As if to underline the absence of natural boundaries – or of anything much to interrupt the endless sweep of waving grass and sparser semi-desert – its population was for centuries mostly nomadic. As herding communities, they had to be.

In Western tradition, pastoral life has, since classical times, been seen as quintessentially quiet and peaceful. The original ‘idylls’ – poems by Theocritus (c.270 BCE) – described the innocent and essentially carefree lives and loves of shepherds. The reality of life for the nomadic pastoralists of the steppes was very different. That ocean of grass once viewed up close looked much less lush: pastoralism was, by its very nature, nomadic. Communities had to be ready to move at a moment’s notice to get the best out of locally variable grazing and water supplies, and this meant the need for enormous areas of territory to be protected.

The ‘Farmers of the Steppe’ in this old engraving now seem quintessentially Russian: for centuries, though, these endless grasslands were wild and unenclosed.

Add to that the temptation to make up for losses in livestock and women by raiding other communities and we start to see why the steppe was an inherently unstable political environment. The nomadic-pastoralist lifestyle at its best could only meet the most basic needs of subsistence. For anything extra, or any luxuries, communities had to look elsewhere. Raiding was an essential and integral aspect of steppe life.

The steppe nomads were a nuisance to one another, but a terror to the settled peoples to the south and west of the steppe, whose communities they would attack from time to time. The farming folk had no real answer to the ferocity of the steppe warriors, nor to the astonishing equestrian skills that went with the nomadic lifestyle; the precision with which they could send arrows whizzing from their short bows at a gallop, wheeling and turning in an instant. The histories of the great civilizations of East Asia, India, Persia, the Middle East, the Mediterranean and Western Europe have all been profoundly affected by the invasions of steppe nomads of one sort or another. They have included the Indo-Aryans and the Hsiung-nu or Huns, as well as the Mongols and Turks of more recent times.

SCYTHIAN UNCERTAINTIES

The Scythians of the first millennium BCE herded and raided their way back and forth across much of what would one day be Russia long before the idea of any such place existed. Where the Scythians themselves thought they were is not clear. There does not seem to have been any ‘Scythia’, as such, only the people, the Scyths (as archaeologists used to call them) themselves.

This makes sense, given their existence on the move. Nomads necessarily travel light, both physically and culturally. They cannot afford to carry extensive archives with them (like the Scythians, they tend to be illiterate) and their connection with the land, although close, is not deep-rooted. We have no real way of knowing where or when the Scythians originated; they appeared in history only when they collided with established civilizations.

Several of the great empires found it easier to make deals with the Scythians than defeat them. Esarhaddon of Assyria may have given one of his daughters in marriage to Bartatua, one nomad leader, around 670 BCE. A generation later, taking advantage of the power vacuum left by the collapse of the Assyrian civilization, Bartatua’s son, Madyes, led his bands against the Median kingdom of north-western Iran. He then pushed westward into Asia Minor before shifting direction south into Syria and Palestine – the Scythians making a brief appearance in the biblical narrative under the name of the Ashkenaz.Ultimately, they reached the borders of the Egyptian Empire. They could have ventured further, but allowed themselves to be bought off by the Pharaoh Psamtik I; as invaders, they were less concerned with glory than with plunder.

A Scythian archer in the service of the Persians, this proud warrior was painted by the Greek artist Epiktetos in around 520 BCE.

AN ELUSIVE ENEMY

The Scythians’ pragmatism was reflected in their reactions in 514 BCE, when Darius I of Persia decided they were an irritation he would no longer tolerate. He marched an enormous army – said to have been 700,000 strong – across the Danube over pontoon bridges and out on to the steppe. Over and over again, reports the Greek historian Herodotus, Darius challenged the Scythians to do battle, but they simply withdrew.

Scythian envoys observe the diplomatic niceties with the Emperor Darius, in this 19th-century representation. On the ground, they didn’t need to fear Persian power.

The Scythians had no cities or infrastructure to defend – not even any fields. With nothing to prove by engaging such an overwhelming force, they vanished away into the steppe. Darius’ army was chasing a chimera. Worse, it was being harried in its flanks and in its rear; having melted away, the Scythians reappeared when least expected, making incessant small-scale attacks that became draining. Darius’ forces were demoralized, and badly depleted. They were fortunate to escape annihilation.

NO MAN’S LAND

The Scythians had their day soon enough. In the third century BCE, another group of nomads started pushing southwest into Scythian territory. The Sarmatians originated in lands to the north and east of Scythian territory, but were themselves dislodged by commotions further out on the steppe. As they were driven further westward, they encroached on the lands of the Scythians, pushing them further westward in their turn. Finally running out of room to manoeuvre, the Scythians were subjected by the Sarmatians and absorbed into their own tribal groups. The Scythians disappeared from history as abruptly as they had entered it – here and gone in the space of a few hundred years.

This was to be the case with the Sarmatians too: in the fourth century CE, another group of nomadic pastoralists, the Huns, started pushing westward out of Central Asia. They too were to roam and raid across much of Russia (and many other countries too). Like the Scythians and Sarmatians before them, they may have had a shocking impact on their first arrival, but they left little trace in history. They too registered only where they clashed with settled and civilized communities that went in for record keeping – hence their villain’s role in the great drama of the Fall of Rome.

After the Huns came the Avars. Again, their exact origins are obscure, but if the Eurasian grassland was an ‘ocean’, these westward expansions were their tides.

As for the steppe itself, that was just the mysterious space they seemed to have emerged out of, and that’s the impression we’ve been left with of the Russian grasslands of that time as well. It was no man’s land, much travelled and ferociously fought over, but ultimately never settled and never truly ‘owned’.

The downward-curving quillon (crossguard) is characteristic of the sword used by the Scythians. Here it’s extravagantly echoed in the curling pommel ornaments.

SKULLS, SKINS AND SCYTHIANS

THE MOST SUSTAINED and detailed description we have of the Scythians and their way of life comes from the Greek writer Herodotus, whose Histories appeared in 440 BCE. It is not clear how much of his report is firsthand, and how much was hearsay, although he is known to have visited some of the Greek trading colonies on the Black Sea’s northern shores and may have forayed inland on to the steppe from there.

Herodotus wrote of the Scythians as a self-consciously ‘civilized’ Greek would write of a ‘barbarian’ enemy, and his testimony should be read with that in mind. However, as sensationalist as it might appear, his account is not considered too far-fetched by modern experts. Although the archaeological evidence relating to the Scythians is scant, neither this nor what we have learned of other nomadic pastoralist peoples seems wildly inconsistent with what Herodotus recorded:

As far as fighting is concerned, their customs are as follows: the Scythian warrior drinks the blood of the first enemy he overcomes in battle. However many he kills, he cuts off all their heads to take them to the king, given that he is entitled to a share of the booty, but this is forfeit if he can’t produce a head. To strip the skin from the skull, he first makes an incision around the head above the ears, then, seizing hold of the scalp, he shakes the skull out forcefully. After this, with an ox’s rib, he scrapes the scalp clean of flesh, before softening it by rubbing it between his hands. From that time on, he can use it as a napkin. The Scyth is proud of these scalp-napkins, and hangs them from his bridle-rein; the more a man can show, the more highly he is esteemed. Many make themselves cloaks, like our peasants’ sheepskins, by sewing considerable numbers of scalps together. Others flay the right arms of their dead enemies, and make of the skin, which is stripped off with the nails hanging to it, a covering for their quivers.

Two warriors fight it out in a field of gold in this stunning scene from the 4th century BCE.

WAVE THEORY

No one knows for sure whether the Sclaveni or Slavs who spilled across the steppe and on into the Balkans in the course of the 6th century CE represented another tide or were the human flotsam that it pushed before it. There is evidence that many of these migrants came on to the Russian plains from further west, in what is now Poland, or from the Carpathian Mountains further south. They were probably the descendants of earlier invaders, from the Scythian era through to more recent times, who had settled in Eastern Europe before being dislodged and dispersed by the arrival of the Avars.

Whatever their origins, the Slavs were soon settled across a wide area of Eastern Europe extending most of the way from the Baltic to the Balkans. They seem to have formed small village communities under local chiefs. Hunting in the forests, fishing in the rivers and streams, they also seem to have done a little farming, albeit on a very small and local scale. These seem to have been peaceful communities, presumably ill-equipped to deal with a new wave of arrivals in the 9th century, this time out of the north: the Vikings.

Trade – in slaves and other commodities – opened up the East European interior. Sergey Ivanov (1854–1910) captures the colour of what could be a very cruel commerce.

VIKINGS WITH A DIFFERENCE

‘From the fury of the Northmen, may the Lord deliver us,’ the monks of England’s Northumbria prayed. God did not appear to have been listening when, in 793, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, ‘the ravages of heathen men miserably destroyed God’s church on Lindisfarne, with plunder and slaughter.’ Raiding groups from Scandinavia spread panic and terror wherever they went round western Europe’s coasts. These Norwegian and Danish Vikings had their counterparts in Sweden. They pushed south and eastward, crossing the Baltic Sea, making their way through Finland and up the Russian river system. As well as ‘plunder and slaughter’, however, they brought trade.

There is a straightforward explanation for this. With so little in the way of a civilized infrastructure – no rich monasteries, no cities, so no treasuries or palaces – there was little here that a raider could seize and carry off. Major monastic and civic foundations in the west had accumulated treasures: gold and silver; gems and jewellery; fine fabrics; illuminated books and leatherwork. But the wealth of this vast and as yet largely unexploited region was growing in the fields – or, more often, running in the forests, for the richest product it had to offer were its furs.

In the West, as here on Britain’s isle of Lindisfarne, the Vikings were known as wild raiders. In early Russia, there was more nuance to their role.

THE RISE OF RUS

Just as, 800 years later, the English traders of King Charles II’s Hudson’s Bay Company started making their way through Canada’s interior offering European products in return for pelts, so the Swedish Vikings plied the rivers of western Russia. They too would find it made sense to establish semi-permanent trading posts; over time, these often took root and grew very slowly into cities. Pskov and Novgorod are both believed to have started out as riverbank bases for trade between Scandinavian Viking merchants and the Russian natives, as did Polotsk, in Belarus, and Chernihiv in Ukraine.

The Finns called the Vikings Ruotsi, or ‘oarsmen’; the Slavic term Rus seems to have come from this. By any name, they were overbearing trading partners; their relationship with the tribes around the Baltic and, further south, in Slavic territories, was no more equal than that between Native Americans and Europeans. The Vikings did exchange goods with the wealthy chiefs they met, but they also appear to have raided defenceless villages and extorted furs from riverside communities. Hiring themselves out to the wealthier chiefs as ‘Varangian’ mercenaries, they involved themselves in local disputes, and soon made themselves an inseparable part of the Slavic scene.

Councillors convene in the city of Veliky Novgorod, a trading centre by the 9th century and soon to be Russia’s first great city.

The differences between the Rus and the Slavs began blurring over generations as a new Scandinavian–Slavic hybrid culture began to emerge. Among its most important centres were the towns of Ladoga, on Lake Ladoga, and Novgorod to the south of it, where a mixed population of Slavs, Finns and Scandinavians lived. As time went on and the Vikings’ field of operations broadened, further settlements sprang up. The chief of these was down the River Dnieper in what is now Ukraine but at this time lay in the territory of the Slavic Polan people.

A VIKING FUNERAL

IN AROUND 920, AHMAD ibn-Fadlan wrote his Risala (‘letter’ or ‘account’), describing a diplomatic mission he had made from Baghdad to the Volga valley. It includes the most detailed description ever recorded of the rituals surrounding the ship burial of a Viking chief: