Table of Contents

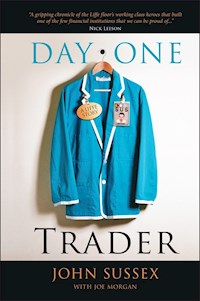

Title Page

Copyright Page

Foreword

PREFACE

Acknowledgements

Chapter 1 - The Chicago Inferno

Chapter 2 - A New Liffe

Chapter 3 - What’s in a Name?

Chapter 4 - Laws of the Jungle

Chapter 5 - The Royal Exchange Days

Chapter 6 - Local Heroes

Chapter 7 - The Crash of 1987

Chapter 8 - Cannon Bridge Boom

Chapter 9 - The Omen

Chapter 10 - Crimes and Misdemeanours

Chapter 11 - Bubble

Chapter 12 - The Liffe Board

Chapter 13 - My Rogue Trader

Chapter 14 - Liffe After the Floor

Chapter 15 - The Last Hurrah

Published in 2009

Copyright © 2009 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Registered office

John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, P019 8SQ, United Kingdom

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com

The right of the author to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Sussex, John, 1958-

Day one trader : a Liffe story / John Sussex, with Joe Morgan.

p. cm.

eISBN : 978-0-470-68504-4

1. Sussex, John, 1958- 2. London International Financial Futures

Exchange. 3. Stockbrokers-England-Biography. 4. Stock exchanges-England- Biography. 5. Finance-England. I. Morgan, Joe, 1974- II. Title. HG5435.5.S87A3 2009 332.64’57092—dc22

[B]

2009013324

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Set in 10.5 on 15 pt Sabon by SNP Best-set Typesetter Ltd., Hong Kong.

FOREWORD

By John Foyle

From time to time Liffe still gets requests from journalists to come to film or photograph its trading floor, and they are invariably surprised and disappointed to find that it shut almost ten years ago. Liffe’s market is now fully electronic; its trading floors are history. And yet the coloured jackets, the sweat, the din, the waving arms, still vividly define what happens in financial markets in the public’s mind. This is a compelling insider’s story of what it was really like to trade on Liffe, and the ringside seats, fast cars, head-turning girl-friends and large houses that success could fund, which at the time made even professional footballers envious.

It is a story John Sussex is perfectly placed to tell. Entranced by what he saw on a visit to the Chicago futures markets in 1981, he became a trader on Liffe when it started up the following year, one of the ‘locals’ risking his own capital who provided vital liquidity to the market and an expert order execution service to the largest financial institutions.

Although John says that Liffe was ‘a somewhat gentrified place compared to the bear-pits across the other side of the Atlantic’, he tells the story as he saw it, warts-and-all. Colourful anecdotes sum up the fear and greed that power the markets, as well as friendship, love, and lust - here is the tale of the dealer who lost $150,000 on a single trade with a female counterpart he had simply wanted to date.

As John says, it was a young man’s job. The physical demands of standing shouting in a trading pit throughout the day, before sorting out stray paperwork afterwards, meant that less than one percent of dealers were over forty. Successful floor traders, he says - drawing on over twenty years’ personal experience - had to be ‘mentally quick to digest the orders being fired into the market while also being tough enough to hold their own on the floor.’ He describes the ‘importance of assuming an aura of invincibility’, crucially distinguishing that from actual, fatal arrogance. Throughout the book John’s own decency shines through.

John Sussex built a thriving business of his own and, having established his reputation, was elected to the board of Liffe in May 1997. This gave him a central role in dealing with the crisis that almost overwhelmed Liffe in the late 1990s, when cheaper electronic trading became available and the exchange saw business in its German government bond contract evaporate in a single year. He found himself facing a dilemma: a man whose livelihood was founded on the trading floor, to whom other traders looked to fight their corner, and yet who could see that electronic trading was irresistible. ‘The Liffe Connect platform’ that Liffe invented, he writes, ‘would support a new generation of technology-savvy traders in London. But for the old generation, its introduction would mark the beginning of the end.’ There are poignant tales of the effect that the transition, which rescued Liffe, had on some of these: the trader who, when using a computer to trade for the first time, picked up his mouse and tried to talk to it, another dealer who did not like the change, became a fishmonger, and used his market nous to buy up cod when flocks of seagulls over Billingsgate suggested stormy weather, and poor catches, out at sea.

Throughout the book there lurks the nagging trader’s fear that a sudden market move, a careless error, an unwise hire, could lead to bankruptcy. For John Sussex this moment came when in 1999, while his firm was adjusting to electronic trading, he took on a trader whose actions almost destroyed him. The episode, and the evaporation of trust it caused, are described in stomach-churning detail. He picked himself up and went on to set up a trading arcade in his home town of Basildon, where he continued to provide the benefit of his experience to younger traders at times when market volatility has surged in this, uncertain, decade.

This is a book primarily about the people who make a market and it was the size of their personalities that made it hard to believe that electronic trading could ever supersede them. John Sussex continues to believe that, in extreme circumstances, it is better to have a human making trading decisions than a computer trading programme. And, chastened by his own experience perhaps, he sounds a warning about the risk of algorithmic trading models malfunctioning and putting banks and markets under dangerous stress.

Inevitably, as with other aspects of this book, not everyone will agree with John’s opinion - and after all, differences of opinion are what make markets. But there was so much more besides that made the Liffe floor market the vibrant icon of the City financial dealing markets. John’s account of it makes for a gripping read.

John Foyle Deputy Chief Executive, Liffe June 2009

PREFACE

The book you are about to read will not teach you how to become a successful trader, it is not a biography as such and it is certainly not a self publicist book - it’s a story about The London International Financial Futures Exchange (LIFFE).

A book like this could have been written by any number of traders who have traded in the pits and on the screens and I am sure they would all have a great story to tell. I was fortunate enough to have been involved from the beginning in 1982 until the exchange was sold to Euronext nearly twenty years later. During that period I was a ‘day one trader’, a local in the pits, ran my own brokerage company, served on the pit and floor committees, served on the Liffe Board and acted as deputy Chairman of the Automated Markets Advisory Group that helped build the electronic platform that they trade on today.

There are no pseudonyms in this book: this is a true story about real people. I have tried to tell it as it happened and really hope that I have not offended anybody mentioned as this was never my intention. I hope you find it a fascinating insight into what it was like during those ground breaking years in the City. I have tried to show how exciting and nerve-wracking it was to trade in open outcry, the characters that made the market, the super traders, business deals and politics - it’s all there!

These were truly great years and I loved every minute of it, good and bad. I never had a day when I did not want to go to work and feel privileged to have made such great friends from the market - this is our story.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My sincere thanks to Joe Morgan - this book would not have been possible without him. I would also like to thank the following who have either contributed or agreed to let me write about them (there are no pseudonyms in this book): Clive Beauchamp, Darren Summerfield, Peter Lester, Nigel Bewick, David Roser, Keith Penny, Ted Ersser and David Helps who all worked with me at Sussex Futures and Alan Dickinson, Terry Crawley, Richard Crawley, David Wenman, Nigel Ackerman, Kevin Thomas, Tony Laporta, Danny Jordan, Mark Green and Roger Carlsson from the floor, also Nick Leeson, Matt Blom and Spencer Oliver.

Finally Nick Carew Hunt, James Barr and especially John Foyle from Liffe and all the staff at John Wiley & Sons for their great support. Apologies to anyone I have forgotten.

1

The Chicago Inferno

The feeling captivated me. I opened the wooden swing doors and a barrage of noise erupted from an octagonal arena the size of a vast football pitch. Scattered across the trading pits on the floor below were the yellow and red jackets of thousands of brokers and traders frantically shouting their orders into the market. Every nanosecond reverberated with the sound of buy and sell orders being spewed into pits strewn with enough pieces of paper for a ticker-tape parade. The intensity of dealing on the heaving exchange floor had created its own hyperreality. What I was witnessing did not exactly appear to me in real time.

I had just caught my first glimpse of the trading floor of the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT) and already I was hooked on the adrenaline of the pits. This was the coliseum of the financial world. It felt like standing in the greatest sporting stadium ever built by man to watch the match of the century. Brokers with physiques like American football players stood on the top steps of the floor and used brute strength to hold prime dealing positions. This was done with emphatic hand signals that I had never seen before. The gladiators in the baying pits would live or die by the numbers being churned out of the ticker-tape machines. Some would leave the floor having made tens of thousands of dollars that day. Others would ‘bust out’ on losses and never return again. As I felt the heat from the fluorescent lit pits I knew this was the type of place I had to be. I wanted a piece of the action.

Joe Duffy, a fresh-faced tubby young man with blond hair, was my guide for the day. A native of Chicago, he had been my counterpart in my job as a foreign exchange dealer in the City of London. My work had taken me to the windy city on a week’s business trip. Squeezed into his yellow broker’s jacket, Joe was doing his best to explain what was going on at the world’s oldest futures and options exchange. Corn, ethanol, oats, rice and soybeans all had their own pits crammed full with hundreds of traders. Dealers were taking bets on everything from the future price of gold to the trajectory of US treasury bonds. The gaping soybean pit was huge. It fell 40 steps deep, forming a battlefield for almost 1,000 traders. A ring of yellow-jacketed clerks stood near the top steps of the pit feeding prices back to the trading booths using intricate hand signals. Financial futures and treasury bonds were traded in a dealing room adjacent to the floor. When I stepped inside it felt like waiting to get into an underground train in the rush hour. The place was packed so full some dealers could lift their feet off the ground and not fall. There was hardly any space for traders to move! The low ceiling and complete absence of any natural daylight only added to the claustrophobic feel of the place.

As Joe made a few quips about the antics that went on in the pits I doubt he had any idea of how spellbound I was by the whole experience. You could smell the fear and greed as sweat-soaked dealers shouted to get their orders heard. The heat from the pits made the entire exchange floor feel like a sauna! Everyone was yelling instructions at the top of their voice. In some pits, dealers were even falling over each other in a mad scramble to get orders filled. The fragments of conversation that caught my ear as I walked past were as brutal and uncompromising as the movements of the market itself. ‘Don’t turn your back on me I’m trading with ya ... I sold you 10 and you’re damn well wearing em ... Ahhhr screw you.’ Back in London, discount brokers donning top hats and three-piece suits were still strolling into the London Stock Exchange with their chins stuck up in the air. Seeing ‘wise guys’ in red jackets, black polo shirts and clip-on bow ties happily telling the nearest chosen enemy to ‘go f**k yourself’ was an eye opener.

The year was 1981. I had just turned 23 and this was my first visit to America. The cluster of skyscrapers in Chicago’s downtown financial district was a long way from my home town of Basildon in Essex. That night in a watering hole near the exchange, my new drinking buddies were getting used to my unusual accent as we knocked back a few large pitchers of cold gassy American beer. It was not long before the guys wanted to hear some cockney rhyming slang, which they thought was hilarious.

After my first day’s visit to the floor I was told a few war stories from the pits. A trader who suffered a heart attack on the floor had been left to die while everyone kept on trading. Before the floor observer had summoned medical help some dealers had even stuffed cards with fictitious trades into the stricken man’s pockets. Unsurprisingly, physical confrontations were a frequent occurrence. In one incident a loud dispute between two traders was settled with a crunching right hand to the jaw which left the victim laid out on the pit floor. An irate floor observer leapt over and told the brawler that he had to cough up an instant $1,000 fine. When $2,000 was stuffed into his hands he appeared perplexed. Did the trader not hear that the fine was $1,000? ‘I know. I’m gonna hit the son of a bitch again,’ the trader replied.

My new drinking buddies were more interested to hear about what life was like in little old England. As I explained the intricacies of cricket and gave my opinion of baseball - ‘just like rounders isn’t?’ - I could see prices coming in from the exchanges on a ticker-tape near the bar. I had already started reading the market reports of the Financial Times in my early morning commute before looking at the back pages of the Daily Express for the latest football news. Now I felt like I was in the financial world’s equivalent of a sports bar. And the results from the markets never seemed to stop coming in.

I asked Joe why he still took an identity card to the bar. I was surprised when he told me that the drinking age limit in America was 21. As an Essex boy who had been drinking in pubs since the age of 15 it was all a bit strange. I still felt a bit like a kid who had just won a dream holiday. I remembered the bell boy who had greeted me the previous evening at the 5-star Hyatt hotel. He must have been a good few years older than me and the cloth of his suit was better than my own. It did feel odd giving him a tip!

I spent the next few days at the Windy City’s other major dealing house, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME). On the approach to the exchange I looked up at the CME’s twin concrete towers which jut out confidently into the city’s skyline. As I breathed in the crisp winter air I felt like I was walking the streets of a town which lived and breathed the financial markets. Thousands of people work in the financial services industry in Chicago and everyone seems to have a view on the markets. While London cabbies talk about football, the taxi drivers in Chicago give their view on where the treasury bonds futures price is heading. When I told people I was a trader it felt like saying I did the best job in the world.

The CME’s trading floor was almost as big as CBOT’s financial amphitheatre. I had a bird’s eye view of what was going on while sitting in a broker’s booth which overlooked the steps leading down to the pits. Here I punched in a few currency trades which I negotiated over the telephone with the guys from the London office. I also got to know people at the exchange and tapped their brains to find out more about the futures market. The guys in the yellow jackets were either clerks - whose job it was to collect trading cards from the pits and input trades - or telephone brokers. The traders in the red jackets were known as ‘locals’. Being a local meant that you traded with your own money. In other words you could make or lose a fortune in one day. This probably explained why a fair few looked on the verge of a seizure when the action kicked off in the pits. Back home in London, the concept of people in a financial exchange trading on their own account was as alien as a City worker turning up to work wearing anything else but a white shirt. It just did not happen in 1981. And dealing was exclusively in the hands of financial institutions. The Chicago pit traders were all interested to hear about the job I did in London. I explained how I would get the best swap rates from the London cash market - which could for example be 200 points for cable Sterling/Dollar - and then make a deduction from the spot rate. So if the spot rate was 1.9525 and I deducted 200 points, the price in Chicago could be expected to stand at 1.9325. If it was different I would buy one and sell the other and when the market corrected itself I would reverse out the position and take a profit.

When my plane landed back on the tarmac of London’s Heathrow airport I knew my visit to Chicago had changed my life. It was not long before I was told about plans for a financial futures exchange to be opened in London the following year and I knew I had to be there at the opening bell for the first day’s trading. Never mind that I had already carved out a successful career as a foreign exchange dealer. My mind was made up.

I had not always been so sure of my destiny. Dealing millions of dollars on the global financial markets had never been suggested to me as a possible career path at my local comprehensive school in Basildon. I was born in 1958 at home in the two-bedroom council house that I grew up in and there were not any expectations on me to succeed academically. I never took the 11-plus exam and I did not know anybody at school that went on to university. The pursuit of excellence at my school was largely confined to the sporting arena. This suited me fine as a keen football player and cross country runner but at 16 I left school with just two low-grade O-Levels and eight CSE passes.

My father, John, was not disappointed in me. Just being an average student was enough for him and he never attended an open evening at the school. As one of 10 children that had been evacuated from the East End of London during the blitz he had not received much of an education himself. He was a lifelong Labour Party voter and blue collar worker who had a job at a battery factory in Dagenham. He expected me to follow in his footsteps as a factory worker. My father would play snooker every Friday night and squander his week’s wages every Saturday at the local betting office. By Monday morning he would always be broke. Seeing my father give so much of the family income to the local bookmaker would have a profound effect on me years later when I became a professional trader. The only interest we shared was a love for West Ham United football club. My mother, Olive, was a housewife and part-time factory worker. While I had a happy childhood - spending many days playing football in the streets and at the local park - my younger sister, Lynne, and I never had the luxury of a holiday.

As a 15-year-old who had served as a dish washer, van boy and market stall assistant among other things I was hopeful of landing a good summer job at Basildon job centre. When I was asked what my best subject was in the classroom I said maths - an ability to be quick with figures and mental arithmetic was always my strength at school. This made me suitable material for a junior accounts clerk position. It was not until I got back home that I realised that it was a full-time job for Cocoa Merchants, a commodity brokerage firm based near Fenchurch Street in the City of London. I had only been after summer work but I thought ‘what the hell, lets give it a go!’

I put on a suit which I had bought for my grandfather’s funeral and got on a train to the big city. The towering buildings and bustle of the City of London’s streets felt a long way from Basildon’s utilitarian shopping centre. I felt a bit intimidated when I stepped through the grand entrance of Plantation House, which housed the offices of Cocoa Merchants. Inside I was greeted by a fair-skinned ginger-haired man from Essex named Bob Smith. Bob was in his late twenties. He was an Essex man from a similar background to myself. But he chose to support Leyton Orient, my football club’s smaller less successful neighbour. Smith must have seen some potential, or perhaps a bit of himself in me, as he offered me the job on the spot. A quick demonstration of my mental arithmetic skills was all that I needed to pass. ‘Will you be able to start next Monday?’ he asked. It would be the only interview I would ever have. My career in high finance had begun.

At Cocoa Merchants I found balancing ledgers easy and I enjoyed finding my way around the accounts department. Epitomising the old ways of the City was the secretary of the firm, an elderly gentleman with balding grey hair, known as Mr Banks. He always dressed immaculately with shiny leather shoes, a black three-piece, pinstripe suit and hard-collared white shirt. He never made the effort to converse and he would watch over me as I added up thousands of numbers for the sales and purchase ledgers. Despite the rarity of a miscalculation he would never let me write anything off until everything had been re-tailed at least three times.

I would often catch a glimpse of the old man looking at me over his half-cut glasses like a disapproving schoolmaster if I was having some banter about a football match the previous night. Just one stare and I would shut up! Each evening before he left the office he would call his wife and simply says the word ‘eighteen’ before hanging up. This was to confirm the train from which his wife would collect him. As a young man I would ponder why he did not just call his wife if he was not taking the ‘eighteen’ train - he never stayed late or left early. The other young starter in the office was a university graduate called Paul James. Like myself, Paul was from the East End of London and very sharp with numbers. He sported long black hair and a beard and always dressed in the most casual suits you could find. He was also from a mixed-race background which was quite rare in the City at that time.

It did not take me long to settle into life in the City. These were the old days when trips to the square mile’s many fine drinking establishments were a frequent occurrence. Never mind that my old man thought that I was not doing real man’s work. Taking home £18 a week had made me rich! I made sure that I would never arrive late, leave early or take a sick day. A year later I had been promoted to a junior trader’s position which involved writing up the dealing sheets and quoting Sterling/Mark for the firm’s German broker, Hans Fritz. I would have done this job for nothing and it was not long before I was dealing everything from interbank deposits to certificates of deposit and Dollar/Mark.

It was around this time that I started dating my wife, Diane, a confident and attractive long-haired girl who wore blonde highlights in her hair. Diane was always the centre of attention in the office. Every evening a high-flying trader would be trying to work their magic and ask her out on a date. She worked as a telex operator to confirm my deals. I used to chat with her when everybody went to the pub but I always felt Diane was out of my league! Being a Chelsea girl from the big city and a couple of years older than me, I found her very different to the Basildon girls I had dated before. But she was very down to earth too - not at all like the Chelsea Sloane princesses for which that part of London has since become famous. We were soon married and I used my £ 1,500 bonus that year as a deposit to buy our first house. It was not long before we had two children. A daughter named Michelle and a son called Paul.

I loved the energy of the dealing room which was kept alive by the infectious enthusiasm of Tony Weldon, the son of the firm’s owner, who was known as ‘old man’ Weldon. ‘What’s going on John? Come on. I need that price now,’ he would yell at me ... ‘That’s my boy. Keep it coming, keep it coming.’ Tony was still in his late twenties and he had an ego 10 times the size of his lean 11-stone frame, topped with black slicked back hair. But I warmed to him and appreciated his enthusiastic manner. Tony’s desk was located in the middle of the dealing room and he would always be jumping to his feet, instructing the traders like the conductor of an orchestra. ‘Come on boys, what is going on? We are not running a bucket shop here,’ he would say. The Weldon family was of Jewish descent and I suspect that they had escaped Germany after Adolf Hitler had come to power. At the time I felt I owed Tony and Bob a lot and I would later decline offers I got from headhunters as I built my reputation in the business.

The Weldon family were good friends with Bill Stern, a leading figure at General Cocoa Company Inc, a Wall Street commodity brokerage firm. When Bill’s son Mitchell came over to London to learn more about the commodity business, Tony asked him to shadow me for a few days. Mitchell’s dark brown wavy hair made him look a bit like Neil Diamond when he appeared in the film The Jazz Singer. Somehow the son of a factory worker from Dagenham and the son of millionaire Jewish Wall Street financier quickly became great friends. Tony encouraged us to go out most nights and explore the city’s nightlife. I enjoyed showing Mitchell around London’s West End and introducing him to Britain’s pub culture. After knocking back a few pints of lager, Mitchell liked to visit some of the more exclusive places in the capital which included some of the city’s best hotels. I remember thinking how surreal it was one evening as Mitchell ordered another bottle of champagne for myself and Diane at The Savoy Hotel. The majestic Art Deco surroundings of one of London’s most famous hotels seemed a long way away from my local pub in Basildon, where my mates were drinking that night.

Mitchell suggested that we go to a restaurant in Chelsea one evening. Tony had introduced him to the establishment earlier in the week and he said that he had been blown away by the place. We ended up having a great night but when the bill came we could not afford to pay. This was in the mid-seventies and I was not one of the few people that carried a Barclaycard and I did not have a cheque book to hand either. We decided to keep ordering drinks while we weighed up our options. Should we do a runner? Offer to do the washing up? In the end we asked to borrow the restaurant phone and tried to call Tony but there was no answer. By this time we were the last people in the restaurant. Luckily I was able to call Diane. She borrowed some money from her mum, jumped in a taxi and came to the rescue.

My career as a trader started to take off at about the same time as Margaret Thatcher’s Britain began. My rapid journey from a pupil at the local comprehensive school to a dealer at a leading brokerage firm was exactly the sort of social mobility the new ruling Conservative Party wanted to propagate. People were being encouraged to ‘get on your bike’ and make their own way in the world. In the square mile, wine bars were starting to open up for business. I could almost taste the new opportunities opening up around me - and I was a young man with a big appetite. I started regularly attending lunches and after-work functions to get my name known in the City. The trappings of success that I was enjoying may sound very modest but they meant a lot to me at the time. Most importantly of all I was given my first company car, a brand new Ford Cortina worth £4,500. Owning a car is hardly the stuff a Wall Street high flyer would boast about. But it was a big deal to me. My father had never owned a car.

More responsibility would come after Cocoa Merchants was taken over by commodity brokerage firm Phillip Brothers. Whereas before I had been doing foreign exchange dealing for the firm’s hedging requirements on cocoa, sugar and coffee futures I was now trading on the company’s own account and executing orders for major firms. This made our firm well known with all the big banks and we started to become one of the biggest traders in the market. One of my clients was Princeton, New Jersey-based Commodities Corporation, which had tentacles in markets across the globe, managing hundreds of millions of dollars. A mystique surrounded Commodities Corporation. The trading company was renowned for using innovative trading methods and its own funds hardly ever suffered losses. Being able to do business with such a big name in finance boosted my own profile in the City. I would receive more invitations from major financial institutions to cocktail evenings and forex seminars. I was hungry for knowledge about finance and these events enabled me to further my education and expand my network of contacts.

I got a special buzz from dealing with Commodities Corporation as it had some of the superstar traders of the day including Mike Marcus, Bruce Kovner and Roy Lennox. Marcus famously had an office which housed dozens of employees built next to his beachside Malibu residence. He would call and ask for my opinion on the market. I would do my best to give the multi-million dollar speculator my view as a young man without a wealth of experience in economics or current affairs. I would explain where I had seen the flow that week. After about 10 minutes he would often make a request to buy $100 million in the opposite direction to that which I had suggested. I would later read an interview in which Marcus said that he would always make sure that he was guided by his own convictions when speaking to other traders, in an effort to ensure that he absorbed their information without getting overly influenced by their opinions. Marcus went on to retire and we did not hear from him for six months. Then out of the blue he called up and said that he was back in the business. All the aeroplanes, holidays and adventures money could buy were no match for the buzz he got from trading. ‘I just can’t leave it alone,’ he confessed.

I had moved up the ranks on the trading floor to become second-in-command to Bob Smith who was starting to carve out a reputation as a star trader. Tony recruited Brian Marber, a specialist in financial charting, and Jim Fleming, an American from Chase Manhattan Bank. When Fleming asked Smith if he would arbitrage the currency futures in Chicago against the London cash market he refused. He was far too busy and important to devote his time to such trivial matters and the job was given to me. This would change my life.

Now I was trading financial futures and my afternoons were spent with two telephones wrapped around my ears while shouting across my desk and doing business with the big exchanges in Chicago. Rather than waiting for the telephone to ring I spent my time dealing and making calculations. You had to be mentally very quick to do arbitrage right as the job was pretty full on. But to me this was intoxicating, like a drug. My 12-hour days just flew by as I got to work on brokering million-dollar trades which ran through the firm’s books like confetti. While it was a joy to work in such a fast paced environment I never lost sight of the fact that I was walking a tight-rope every day. Make one mistake as a trader and it could easily be your last. I saw this for myself first hand when a gangling lad a couple of years older than me called Gordon got an order the wrong way round one lunch time. I spotted the error as soon as I got back to my desk and reversed the position out at a big loss. While it was not my fault I felt very nervous about the whole episode but nothing was said to me. Gordon was called into the boss’s office that afternoon and sacked on the spot. I never saw him again.

Trading desks are unforgiving places where the strong prey on the weak. A fresh starter can expect to be tested by experienced market veterans with a rat-like cunning for spotting an opportunity to make some easy money. Their victims are often left cursing their ‘bad luck’ while they find themselves looking for a nine-to-five desk job elsewhere. A bank trading desk is not always the most friendly place to work either. ‘If you want a friend, buy a dog,’ did not become a classic Wall Street expression for nothing. One trainee dealer at a Wall Street bank found himself being completely ignored by the bond trader he was shadowing. It would be three months before the trader asked him to do anything apart from sending him on errands to buy coffee or junk food. ‘I have to pop out for half an hour. If anybody calls, make sure you quote a two-tick market in five million,’ ordered the bond trader before leaving the fresh-faced trainee to wait nervously by the telephone. After five minutes the receiver rang.

‘Hello, and who is it zhat I am speaking to,’ asked a customer from a Swiss bank.

‘Err, I’m the new guy. Sorry. I mean I’m just covering the desk for a few minutes,’ mumbled the trainee.

‘Veil hurry up and quote me ze prices,’ said the Swiss banker.

‘Err ... Okay six bid at eight,’ said the trainee after taking a quick glance at the prices in the market.

‘Stimmt. Five million mine at eight,’ replied the banker.

‘Oh ... Well thank you.’

‘No no no young man,’ said the banker. ‘Vere are ze prices?’ Knowing the banker was a buyer, the trainee changed the price to seven bid at nine.

‘Five million mine at nine,’ said the banker.

‘Okay sir,’ said the flustered trainee before he was interrupted again.

‘No no no no young man. Vere are ze prices now?’

‘Err. Eight bid at ten,’ said the young dealer. He had never wanted a conversation to end so badly.

‘Five million mine at ten,’ said the banker.

‘Err thank you sir and err ...’

‘No no no no young man,’ interrupted the banker once again. ‘Young man can you make me a price in fifteen million. Then I’m done.’ All the trainee wanted to do was check the market but the customer would not let him off the telephone. This left him in a state of panic. These were his first ever trades and he had just taken on some massive positions.

‘Twelve bid at 14,’ said the trainee, reasoning that there was no way the customer would want to pay 14. He was right.

‘Fifteen million yours at 12,’ was the banker’s quick reply. ‘And ... Velcome to ze club my friend.’ The telephone line went dead. The trainee was left to desperately check the market. He had sold treasury bonds at eight, nine and 10 before buying them back at 12 - but the market had not moved. He had been had! The treasury bonds had a value of $100,000 and each tick was worth $31.50. Selling $ 5 million at eight, nine and 10 before repurchasing at 12 had just cost him $14,175. When the bond trader returned to his desk he would find a distraught trainee almost lost for words when trying to explain the thousands of dollars that had vanished without a single market move.

I was told that I would be Cocoa Merchants’ floor manager when the London International Financial Futures Exchange (Liffe) opened. This was my chance to get out of Bob Smith’s shadow and be my own boss. It was June 1982, just three months before the Liffe floor would open, and I was hit with a bombshell. Phillip Brothers had merged with Salomon Brothers. The tie-up was sold as a marriage of ‘Salomon ingenuity’ and ‘Philip cash’, which enabled Salomon to further expand its investment banking activities. But it was bad news for me. Salomon would take responsibility for managing the floor operations at the new Liffe exchange and the only position available to me was as clerk for Ted Ersser, the man given the floor manager’s job. I felt I was better than that and my pride and ego would not let me take that role. Ersser was a very different animal to myself. He would never put on a trading jacket during his entire Liffe career. A swanky grey suit with bright red braces was much more his style. I assumed that he had been public school educated but he was in fact an ex-grammar school boy who had even spent some time cheering on his beloved Chelsea in the more raucous section of the Stamford Bridge crowd during his teenage years.

Word got out that I was not happy and Heinold Commodities, a Chicago-based broker, offered me the opportunity to run their operations at Liffe. I jumped at the chance. Heinold had two seats, one booth and employed a clerk to assist me. A young polite blond woman named Clara Furse - who was destined to become chief executive of the London Stock Exchange - would work on our broker desk. Furse was strong-minded and always very professional. Handing in my notice was not an easy decision. I had two children and a £50,000 mortgage. Tony Weldon tried hard to persuade me to stay, telling me that the Liffe exchange was doomed to fail. He had already talked me out of taking a great offer from the commodity broker Marc Rich in the past. But even the advice of my trusted mentor could not stop me. I had absolutely no doubt that I had found my calling. Diane backed me and I knew there was no turning back now. It would be the beginning of a new Liffe.