23,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

Capturing the landscape on paper requires the artist to look - to look deep into the distance and deep into the soul. This practical book celebrates the genre of landscape painting - the wonder of discovering the extraordinary in the everyday scene. Philip Tyler looks in detail at the materials, techniques and approaches needed to paint the landscape, and offers advice on how to portray space, light, atmosphere and different weather conditions. Supported by the words and images of other notable artists, he explains how to transfer one's emotional response to the landscape onto paper or canvas. There are exercises to support the 50 lessons in the book and over 300 colour images illustrate the text.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

Drawing and Painting the Landscape

A course of 50 lessons

Philip Tyler

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2017 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2017

© Philip Tyler 2017

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of thistext may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 325 7

Frontispiece: Brancaster Staithe Tears, acrylic on board.

Contents

Preface

Introduction

Chapter 1Materials

Chapter 2Linear drawing

Chapter 3Perspective

Chapter 4Tonal drawing

Chapter 5Mark making

Chapter 6Composition

Chapter 7Painting

Chapter 8Colour

Chapter 9Ideas

Artists’ websites

Acknowledgements

Further reading

Index

Patrick George, Curtain of Trees (2000), oil on board. (Courtesy of Browse and Darby Gallery)

Preface

The day had started promptly enough. A light scraping of ice on the windscreen. A car full of the things I would need to interview Patrick George: a camera, my phone to record the interview and a few gifts too. Five or six turns of the car key confirmed that my car was dead and a faltering battery was indeed not fit for much else. An hour or so later, the AA man was on his way; for what would be a busy day, I set off on my journey. As I drove through West Sussex, my thermometer hit -8°C at one point, but the landscape did not seem that cold, bathed as it was in a golden light. Driving through Essex, the countryside became an altogether different vista; heavy cloud created a muted space, a subdued series of colour patches, a flat pattern of shapes. As I entered Suffolk, the space seemed to stretch away from me but formed a thinner, more compressed landscape. The air began to lift and colour began to seep in, permeating the landscape, bringing it back from grey.

As I entered Patrick’s house, greeted warmly by both Patrick and Susan, and the fresh soup and bread that Susan had made that morning, I saw that his house seemed to have light coming in from all sides. On the walls were fellow comrades in arms, a Tony Eyton, a William Coldstream, a Craigie Aitchison, and a Jeffery Camp, each one quietly exuding their presence on the space. After this delicious fare, I began to talk with Patrick and he began to interview me.

Why paint landscape? His eyes looked straight at me, making me justify my own responses to the North Norfolk coast and the Sussex Downs. I discussed the emotions and recollection one had in front of a particular space. At that moment, I wished my phone were on record; his thoughts sparkled in the room, which seemed to light up in front of me. Eventually, my phone switched on and our conversation developed over the next hour. We talked about us both growing up in an urban environment, he Manchester, me London, and the notion that the landscape may have offered us both an escape, a chance to look into the far distance rather than at one’s feet. We talked about drawing, about colour and more than anything about really looking.

As the interview developed, the light seemed to grow in luminosity, moving across the floor and gradually riding up over Patrick himself. His face became bathed in the most glorious intensity; the loaf, soup bowls and coffee cups became magical and luminescent. Every so often, Patrick would look away from me, and stare out of the window into his garden. I knew what he was thinking, he was probably waiting for the moment when he could paint that view. His oil paints and easel already there in preparation for the moment.

You tend to think of great paintings in galleries, private collections or museum walls. You don’t expect to see paintings that you have grown to love, stacked up against the wall with their backs turned. Susan later unveiled each in turn, a view of Hickbush, a Saxham tree, the facade of a building; paintings I have grown to love since my first encounter with a George back in the mid 1980s at the hard won image show. What touched me then was this simple idea: paint what you see, discover the extraordinary in the everyday. That painting with its electrical pylon rooted itself in my psyche. Its flatness, a configuration of shapes and colours, a mutable landscape, Patrick had revisited the same spot over and over again. Finding that the space had changed, he simply recorded his new experience, trying to make sense of his visual experience.

Within a year of that show I was studying in America, experiencing a light I had never seen before, a magical light, intense, clear and richly saturated. Everything seemed to be in sharp focus, and it was during that time I saw my first Richard Diebenkorn.

Patrick George, Winter Landscape, Hickbush, late 1970s. (Courtesy of Browse and Darby Gallery)

Whilst I never made the connection back then, as I looked again at these Patrick George paintings in the flesh I saw parallels, the often-rectilinear movements of the landscape punctuated by diagonals, the evidence of contemplation, the need to get to some kind of truth that could only be arrived at over time by dedication, questioning and transformation. Would this colour work? How could one capture the experience of light falling on that leaf? I was rather interested in Patrick discussing his choice of Suffolk. Somehow there were fewer leaves on the trees here, less obstacles to deal with, yet his paintings are full of the problems he has set himself to solve. When I asked him about what aspect of landscape he was trying to convey, he simply said that he just wanted ‘to do the best he can.’ Like a bird resting lightly on a branch, Patrick’s touch is a delicate one, barely breathing the paint on the surface of the support. His paint tubes, and there were many greens, are testament to time some seemed to hark back to an earlier age.

It was once said that Coldstream’s brushes were perfectly clean and free from pigment, cleaned constantly in the process of making a mark, his indecision becoming a nervous set of ticks. I’m not sure if George is so bogged down by measurement, his canvases have a decisiveness and breadth of mark, that suggests he is not anchored by measurement, but they are full of contemplation. The loaded gestural attack of Bomberg or Auerbach, the trail of the hand not part of George’s oeuvre. Instead, his luminous canvases are full of light and air. Again I am reminded of Diebenkorn and his Ocean Park paintings, whilst the saturation of Diebenkorn’s paintings are permeated with Californian light; they have the same touch. They say you should never meet your heroes. Whilst I never met Richard Diebenkorn, I have a handwritten letter from him. When I received this in the mid 1980s, I was touched by the humanity of the man. He was honoured and flattered that I had so forthrightly engaged with his paintings, and I felt the same kind of connection with Patrick, a man of exacting visual intelligence, conviction but also humility. I came away from his house and before I got into my car, I realized that I was surrounded by the subjects of his paintings. Those trees in a field, that branch and roof; everywhere I looked I saw another of his paintings. On my way to Suffolk, I reflected on all those landscapes I had seen and how many Patrick George paintings could be made. On my way home I had a similar experience, every view seemed filled with the light in his work.

Patrick George, Hickbush, Extensive Landscape from the Oaks, 1961. (Courtesy of Browse and Darby Gallery)

Postscript

Three months after I interviewed Patrick, I received an email from his gallery, Browse and Darby, that he had sadly passed away on the weekend.

Richard Diebenkorn, Untitled No. 10.

Introduction

There is something beautiful about a melancholic cloud hovering in the sky, a moment when the light breaks through, giving clarity to a feature in the landscape. One takes a breath, looks across the distant view and stares in awe at the immensity of the space, the notion of self, disappearing into the distance. To capture that feeling, to put down on paper or canvas that emotional response to the landscape, to encapsulate all those memories and moments of experience and somehow make that concrete in paint, that is the challenge for the artists deciding to explore landscape as their motif.

What do you think of when you look at the title, Drawing and Painting the Landscape? Do you think of Constable (1776–1837) or Turner (1775–1851), Gainsborough (1727–1788) or Corot (1796–1875), Monet (1840–1926) or Pissarro (1830–1903) or do you delve back further to Rembrandt (1606–1669), Rubens (1577–1640) or Joachim Patinir (1480–1524)?

The history of landscape painting is a long one and within an eastern tradition, even longer. The Chinese scroll paintings made over a thousand years ago create a sense of majesty and awe in the viewer; a place of contemplation and wonder, yet made with an economy of means that deny the skill and mastery of the medium. The Chinese said that a painting was made with the eye, the hand and the heart.

Within a European tradition (the word landscape itself did not appear in the English language until the early seventeenth century) early Gothic landscape started off as a backdrop to a staged drama, acting out some biblical narrative. These imagined places simply create a place for the action, but eventually the landscape would become more than just generic trees and hills, the location would become imbued with character and meaning.

A painting made when I was fifteen, one of my first landscapes. Gouache on paper with airbrushed sky.

Mirroring the world in paint is my major preoccupation, but landscape and the bodies that inhabit it is my main subject.

– NICK BODIMEADE

One of the landscapes I made from Beacon Hill, circa 1984.

My first plein air painting, circa 1984.

After the Reformation, the subject of landscape painting became a genre of its own. Artists throughout the centuries have wrestled with the problem of describing space, light, atmosphere and differing weather conditions. Some found within landscape a vehicle to convey much more than a scenic inspiration. John Martin (1789–1854) could demonstrate the hand of God, Turner the tumultuous sea and Constable the notion of heritage and place. It is interesting to note that landscape became increasingly popular during the industrial revolution. As Tim Barringer said, ‘As Britain became predominantly urban, images of the countryside came to stand as emblems of the nation itself.’

While cities rose, and country folk left behind their past, skills and way of life, the middle classes created this idyllic notion of the landscape. Trains tore a hole through the landscape, the country became smaller and remote locations became places of spiritual solace. Ruskin found beauty in the landscape and tried to capture it in exacting detail. The Pre-Raphaelites would take their canvases onto location to work directly from the landscape and their counterparts in France were doing the same. The notion of plein air painting might be one that we take for granted, but it was born at the end of the nineteenth century. It is important to remember that Constable worked directly in the landscape to produce oil sketches that would have never seen a gallery wall in his day. Constable’s paintings were looked on as too vulgar, too true to nature to a public used to looking at the landscape though a blackened piece of glass.

Today, in a contemporary art world full of photography, video sound and performance, why do some artists still want to put pen or brush to paper or canvas? Of course, context is everything and in a small number of high spec museum galleries, there is a lively engagement with rhetoric and theory, and art works become objects of enquiry, exploring new media, new technology, new thinking. But in a large number of commercial galleries, run by people who have their own visions of the art world (one that doesn’t necessarily resemble this bubble), private collectors buy paintings for their homes and artists struggle with the alchemical process of turning mud into place, line into distance, colour into space.

Many of the artists contained in this book are people I know personally, either through direct contact or through my experience of their work. For me, there is something quite magical about the transformation of base materials into image, which leave behind the mark of the artist who made it. The first time I saw a Rembrandt in the flesh, I was struck by the physicality of the paint. One could feel the hand that made the mark. The same can be said of a David Atkins or a Louise Balaam. So I am drawn to those artists who exhibit a certain kind of physicality in their paint application and who convey something of the majesty and emotion of the landscape of their work.

There is a romantic idea about the artist striding through the landscape, painting materials in hand, to find some magnificent vista and then transcribe it to canvas.

For the amateur artist, the idea of a painting holiday, travelling to some beautiful location, brushes and canvas in tow, holds considerable excitement, but painting landscape presents many technical as well as philosophical challenges.

My relationship with landscape painting has been a long and circuitous one. Growing up in an urban environment meant that I knew little of the horizon as a child. Surrounded by tower blocks, their monumentality had a visual impact upon me. Studying at Loughborough College of Art and Design meant that I saw deep space for the first time. I attempted plein air painting, had my eyes opened to negative space by early Mondrian, but it was a student exchange to America that introduced me to the work of Richard Diebenkorn who was to have a more profound effect on me.

Landscape is a major preoccupation and it was the first thing that I really got excited by painting, and being involved with. It wasn’t until I moved to the country that I started to look at other subjects; having been born in the city, I kind of missed city life so I started to explore that as well, but I have always been fascinated by the interpretation of landscape and what landscape stands for in terms of how it moves you and touches your soul. It can stand for very deep held feelings that come through myself as a human being and I think that landscape is the one thing that takes your breath away; it reaches a depth in me and touches something that’s beyond words and that’s what started my interest in landscape. From very early on I was encouraged to go for walks in parks and woods in London. It was those that I really found I responded to in a physical and spiritual way that linked itself as a subject that was appropriate for me or inspiring for me as a painter.

– DAVID ATKINS

In the early 1990s, my mother and father-in-law John and Joan Dixon, both keen amateur artists, had moved to Norfolk, very close to the north Norfolk coast. Every holiday was spent with them and my wife and eventually our children, long days on the beach at Brancaster, enjoying the vast expanse of sand, the low horizon and those skies. John introduced me to Edward Seago, his economy with watercolour and his grandeur with scale. I spent many hours drawing and painting the views and as our children grew up, Norfolk became their playground.

My first gallery dealer was based in Norfolk, not far from where the Dixons lived. Iris Birtwistle was an amazing woman; nearly blind, an art dealer working out of a caravan, she had an immeasurable passion for her artist. Whilst her vision was diminished, she had an amazing eye and could tell good from bad. She could be forthright in her opinion and demanded the best work from me but she was an essential part of my journey to become an artist.

Brancaster Beach, acrylic on paper, circa 1996.

In recent times, the landscape has become my dominant obsession, in particular the terrain where I live in West Sussex, the Downs, and the effects of the weather have become important vehicles to express emotion, particularly since the death of my father. Landscape can be melancholic, brooding, uplifting and even spiritual at times, and to a certain extent I have allowed it to swallow me up. Some artists choose landscape as their major preoccupation, others as part of a much larger oeuvre. I work in a serial way, focusing on a motif and exploring that for a long period of time before moving onto another motif, rather like Nick Bodimeade.

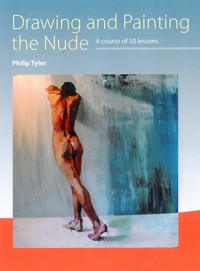

Following on from my first book, Drawing and Painting the Nude, I would like to guide you through some of the technical and theoretical challenges that landscape presents.

Over the next fifty lessons, I will cover materials, techniques and approaches supported along the way by words and images of other artists who interpret the landscape in their own way.

In so doing, I hope to give you a much greater insight into how you can interpret the landscape and find your own voice in painting or drawing it.

Mirroring the world in paint is my major preoccupation, but landscape and the bodies that inhabit it is my main subject.

– Nick Bodimeade

Landscape is a major preoccupation and it was the first thing that I really got excited by painting, and being involved with. It wasn’t until I moved to the country that I started to look at other subjects; having been born in the city, I kind of missed city life so I started to explore that as well, but I have always been fascinated by the interpretation of landscape and what landscape stands for in terms of how it moves you and touches your soul. It can stand for very deep held feelings that come through myself as a human being and I think that landscape is the one thing that takes your breath away; it reaches a depth in me and touches something that’s beyond words and that’s what started my interest in landscape. From very early on I was encouraged to go for walks in parks and woods in London. It was those that I really found I responded to in a physical and spiritual way that linked itself as a subject that was appropriate for me or inspiring for me as a painter.’

– David Atkins

The urge is to rise to the challenge and understand pictorially what I am responding to. Sometimes it’s hard to know until you’re in the process and it feels right to try and make sense of it. In a sense you possess it somehow and as a result experience it deeper by seeing it.

– Julian Vilarrubi

For the past thirty years I have lived in the rolling countryside of the Oak Ridges Moraine, an ancient land form located just north of Lake Ontario. I roam this unique place in all seasons, and document my impressions. It seems very important to record both the appearance of places, and the nature of my response to them. And I have to do this on a daily basis, almost as if a record needs to be kept. I walk to locations every day and this slow process of looking reveals the character of the places I visit. I paint the landscape because it is where I see the most richness, complexity, and meaning. I love and need this beautiful place … the paintings come out of that.

– Harry Stooshinoff

Landscape could convey everything I wanted to communicate, with a power and mysterious subtlety that continues to challenge and excite me.

– James Naughton

Because it’s universal. It speaks to you, landscape speaks to you, doesn’t it? It’s full of emotion.

– Piers Ottey

I find there’s nothing like being outside – the changes in the weather, the sky and the light are endlessly fascinating and engaging for me. I love the idea of a multi-sensory experience – being extra-aware of smells, texture, sometimes the taste of salt on the breeze, as well as sound and sight, all coming together as part of that particular place. I aim to communicate these different aspects somehow in my paintings.

– Louise Balaam

CHAPTER 1

Materials

As one stands at some high promontory, and looks across at this vast space, at the tiny markers of human existence, the ant-like cars catching the light as they trail through country lanes, a bale of hay in a field. One ponders the problem of how one can do justice to all this space and light with a sketchbook and some simple drawing materials.

A range of basic drawing tools and two sketchbooks of different sizes. Note the bull dog clip to stop the pages flapping around in the wind.

Many things are capable of making a mark on paper and can be used to respond to the landscape. There is an intimate relationship between the artist, the material, the support and the scale they work. You will find that one medium is better for the kind of drawing you want to make, but one needs to play with media to know how it can be used and what it can be used for. Only by challenging what you do already will you grow as an artist and become familiar with the unknown.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!