22,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

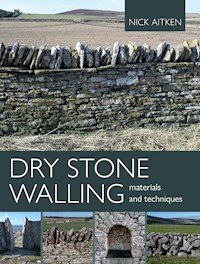

Dry stone walls – the thousands of miles of stone ribbon stretching across the landscapes of the Scottish Highlands, Yorkshire Dales and Cotswolds – use construction methods which have existed for thousands of years. Indeed, dry stone structures in the Orkney Islands and Ireland are even older than the Egyptian pyramids. A dry stone wall is more than a pile of rocks. It is a carefully built combination of specialized stones, each co-operating with the other to create something useful, strong and attractive. No mortar is used. The wall relies on friction and gravity, and the skill of the builder, to keep it together. The basic building principles are easily learned and this book provides step-by-step instructions to develop the skills to build many different types of wall and structure. With nearly 200 photographs and diagrams,

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

First published in 2023 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2023

© Nick Aitken 2023

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7198 4168 2

Photos contributed by: Lluc Mir Anguera; Daniel Arabella; Dry Stone Conservancy, Jane M. Wooley; Drystone Walling Perthshire, Martin Tyler; John Bland; Sean Donnelly; Jared Flynn; Neil Rippingale; Ben Schultz; Maya Stessin; Nicolette Stessin; David F. Wilson.

Cover design by Blue Sunflower Creative

Contents

Dedication and Preface

Chapter One The Development of Dry Stone Walling

Chapter Two Types of Rock, Sources and Quantities

Chapter Three The Basics of Working with Stone

Chapter Four Laying, Trimming and Securing Stone

Chapter Five Constructing a Dry Stone Wall

Chapter Six A Gallery of Wall Types and Bonding Patterns

Chapter Seven Special Circumstances and Obstacles

Chapter Eight Repairing a Gap

Chapter Nine Retaining Walls

Chapter Ten Openings, Arches and Roofs

Chapter Eleven Modern Walling: Pushing the Boundaries

Chapter Twelve Practical Advice for the Novice

Chapter Thirteen A Final Challenge

Glossary

Bibliography

Useful Addresses

Index

Dedication and Preface

A Dedication

I dedicate this book to my wife Nicolette, and the wallers and dykers who generously shared images and information about their work. The craft is in safe hands.

A Preface

Georg Müller (2013) estimated there were 520,552 miles (837,750km) of dry stone walls in the British Isles in 1880, which would have taken 1.9 billion man hours to build. Many of these walls no longer exist. Most were built by teams of contractors in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. There were no formal apprenticeships. Wallers learned on the job, guided by experienced men whose skills were obvious, yet difficult to define.

In 2018, UNESCO recognized the walling skills of Croatia, Cyprus, France, Greece, Italy, Slovenia, Spain and Switzerland by adding dry stone walling to the representative list of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. This acknowledges the expertise of wallers and their contribution to the cultural landscape, wherever they work.

We constantly hear that dry stone walling is ‘a dying art’ (a refrain since the 1930s). Nowadays, with the benefits of international communication, a huge database and an increase in the awareness of environmental and conservation issues, there is ample evidence that the craft is alive and safe, in the hands of several international dry stone walling associations.

Whether you are a complete novice, or a waller with some experience, this book aims to provide you with some, or more, insight into the historic development and building methodology of dry stone walling, and inspire you with examples of new structures built using only stone, held together with friction, gravity, symmetry and balance.

Whatever your level of experience, the ideal way to develop the skill is to do it. Contact your local walling association (details at the back of the book) and take part in their training events or monthly gatherings. Join a stone festival, like Northstone Stonefest in Caithness, Scotland, or those in western Ireland and throughout North America and Europe. These cultural experiences offer the opportunity to learn, establish contacts and become a part of the larger stone community.

Dry stone walling has a specific and specialized terminology. Hopefully the terms are self-explanatory within the text, but some can be clarified using the cross-section on page 51 and the glossary towards the end of this book.

Chapter One

The Development of Dry Stone Walling

Dry stone walls are termed ‘dry stone dykes’, ‘drystane dykes’ or simply ‘dykes’ in Scotland. The terms are used interchangeably in the following text, depending on the location of the structure.

A Brief History

Dry stone walls are a common feature in the British landscape, dividing fields and crossing moorlands, creating an impressive network of human endeavour. What we see today is a relatively recent addition, most of it built since 1700. The earliest agricultural walls were not sophisticated but they were effective, although they were often little more than rows of large stones, set on edge, with smaller stones between.

Dry stone construction is an ancient building technique that does not use any type of mortar. It relies on friction and gravity to keep stone in its set position.

Ancient Walls

Indigenous cultures have built with stone for thousands of years. They built dry stone fish traps, irrigation systems, livestock enclosures and hunting hides all over the world, including the Middle East, southern Africa, Australia and North America. The likelihood of these cultures interconnecting is remote, therefore this type of construction is an excellent example of an instinctive use of local material by a wide range of local peoples.

There is a long history of building with stone in the British Isles. The buried walls in the Céide Fields in County Mayo, Ireland are the remains of a Neolithic farming system dating back about 5,000 years (McAfee, 2011). No description of mortarless stone construction can go without mentioning Maes Howe and Scara Brae in the Orkney islands. These structures, at 5,000 years, are as old as the Egyptian pyramids at Giza.

The earliest walls at Roystone Grange, in Derbyshire, England likely date back more than 3,000 years (Hodges, 1991). The landscape around the Grange includes evidence of ancient stone walls and much younger walls; stones were recycled over the ages as farming practices changed.

Gallarus Oratory and Skellig Michael in Ireland date back nearly 2,000 years.

In Malham, North Yorkshire, stone walls date back to the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries (Lord, 2004). They were built round the monastic sheep pastures to protect their sheep and their wool profits. These walls had less batter, were nearly vertical, and not so refined as the dry stone wall types that were built since the 1600s.

Apart from the walls round these monastic sheep farms and hunting grounds, most walls prior to the seventeenth century were described as ephemeral or seasonal. They protected the summer crops, required a lot of maintenance and were often allowed to collapse in the winter. Livestock, mainly cattle at that time, were kept on the common grazing land and only allowed into the cultivated areas during the winter, to clear up what was left in the fields after harvest.

An older style of dry stone wall, with upright slabs and small stones, in ruinous state. This structure uses available stone in the most efficient way. Age unknown. North Uist, Scottish Hebrides.

A Need for Permanent Boundaries

A radical reorganization of agricultural in Great Britain started in the seventeenth century. The Enclosure Acts stripped smallholders of their rights to graze on the common pastures and, in the name of efficiency, passed the ownership to fewer and fewer landlords, who set themselves up to make a good income from wool, beef and grain. Setting boundaries became important, and there was a need for reliable field boundaries to protect crops and livestock. A more permanent walling system was required.

Various systems of ditches and mounds of earth, sometimes faced with stone and a hedge, were tried. Hedges were one answer but they were slow growing. One development was the turf and stone dyke. This wall was easily constructed out of the local rock, and the turf cut from the foundation trench. There was no need to calculate a tight fit, as the weight of the stones squeezed the turf into the gaps. This type of wall was robust and required less maintenance than previous walls or fences, but it had one obvious disadvantage – it used turf stripped from the pasture, in addition to the turf cut for the foundation. This was valuable grazing that took a year or more to fully regrow. On some rocky ground, it might not even have been possible to find enough turf for such a wall.

Rainsford-Hannay (1976) tells us dry stone dyking, the building of freestanding dry stone walls as we know it today, was first developed in southwest Scotland around 1700.

Dry stone walls were an important development in agricultural fencing. They were a universal answer to a universal need, made from a cheap local material. A stone wall has many advantages over a hedge or a wooden fence: it provides good shelter, is durable, and easily built out of local materials by local workers. Possible downsides are that it is immovable, can harbour pests and takes up too much room.

Thousands of miles of fencing were required as agriculture reorganized into large estates with tenant farmers. Boundaries had to be defined over remote moors and hillsides. Mortared walls were a possibility, but the costs and inconveniences of lime mortar (the only option at that time) made them expensive. Older styles of mortarless stone walls existed; they were finessed to produce a permanent structure that could be relied on to protect boundary lines and livestock bloodlines.

Early commentators wrote passionately about the benefits of dry stone walls, emphasizing the importance of batter, copes, throughstones and hearting. These elements were already well known to the builders of ancient stone structures, and the masons who built mortared walls. They were now applied to the construction of slim, tall agricultural walls.

This new type of dry stone wall was what we now call the standard free-standing ‘double wall’ (seebox). Agricultural commentators in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries advocated this design both at home and in agricultural journals overseas. It was a teachable process and a growing workforce specialized in building them. Many regional variations evolved, depending on the local geology. The basic design was flexible, and adaptable enough to suit every region, from the limestones and siltstones of northern Scotland to the granites of the Cairngorms and the limestones of the English Cotswolds. Walling became a skilled trade, rather than a part-time job.

A turf and stone dyke or ‘feal dyke’, named for an old Scots word for turf. This easily constructed combination of materials is an ideal starter home for rabbits. Highland Folk Museum, Newtonmore, Scotland.

Wall Building at its Peak

Meanwhile, the farmers in Europe and North America were developing their own styles of wall. Europeans especially developed retaining walls. The amount of dry stone field walling in Europe should not be underestimated. Georg Müller’s calculations (2013) for the year 1880 show that France, Greece and Spain each had more dry stone field walls than Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Sweden, a country we do not usually associate with such walls, had only slightly less.

The 1800s were a busy time for wallers. Fortunes were made in the wool trade, on both sides of the Atlantic. Stone walls were essential for management of sheep. Kentucky benefited from the – mainly Irish – immigrants who built miles of free-standing double-faced dry stone walls out of the local limestone. Scottish and Irish wallers worked for Australian sheep stations.

The New Englanders tidied up the accumulated stones round the edges of their fields to build their own unique style – low, wide walls with flat slabs across the top. There is no question that during the construction of these walls they were recycling some stone used by earlier indigenous people for their walls.

By the early 1900s, however, dry stone walling was in decline, as most of the walls that were needed had been built; consequently, wallers tended to concentrating on maintenance work. Newspaper articles from before 1939 were lamenting the decline of the craft and the loss of another country skill. This trend has now reversed. Awareness of dry stone walling is increasing around the world, and many old walls are being restored by conservation groups. Patrons are willing to support high-end projects – work that still uses the traditional methods of construction but with more detailing and greater accuracy.

Two Main Types of Wall

A double wall or dyke consists of two outer faces of carefully laid stone, usually with long narrow stones (throughstones) connecting the faces at approximately half height. An arrangement of coverband and copestones caps the wall off. The interior of the wall is filled with hearting – smaller angular stones that secure the larger face stones. This type of wall is typically 28in (71cm) wide at grass level and 14in (36cm) wide under the copestones. The cope is usually formed out of flatter stones set vertically on edge. The total height might be 4–5ft (1.2–1.5m) for walls round arable fields, and taller for boundary walls between estates. These are by far the most common type of wall.

A section across a double dyke, clearly showing its most important feature – the two outer skins of face stones and the smaller stones (hearting) in the middle. Protruding throughstones are visible in the background. The copestones have been dislodged. Knoydart, Scotland.

The single wall or dyke is the best way to use up large stones or boulders. This style of construction is one stone wide, from bottom to top. The largest stones are laid as a foundation course. Smaller stones are laid on top of that, until the wall reaches the required height, which can be 4–5ft (1.2–1.5m), and not much wider than a double wall. If a single wall is built with mechanical assistance, it can be up to 11ft (3.5m) high (MacWeeney and Conniff, 1998).

A single dyke, one stone thick, built using boulders. It was constructed from left to right, up the slight slope. This would also be described as a ‘boulder dyke’. Some of the top stones have fallen, but this is an easy repair. Southwest Scotland.

There are also ‘triple’ walls. This term is used to describe double walls with another face of stone laid up against them, to use up stone cleared from the fields.

The Influence of Local Geology

There are as many types of wall as there are types of stone. Walls look different because each stone type has characteristics that dictate how it can be used. No matter how the wall is built or the stone type used, they all rely on the same basic principle: a stone, properly laid, in solid contact with its neighbours, will not move.

The type of wall, and how it is built, depends on the available stone. For three centuries, local wallers have used their local stone the most efficient way they could to produce a stock-proof fence. No time was wasted on unnecessary detail.

Dry stone walls in the mountains of Scotland or northern England use rougher stone, and look rougher, because that’s the local geology. They look very different, but serve nearly the same function as the more precise limestone walls in the south of England.

Another factor influencing the style of wall is, of course, the job they do. The mountain walls were built to enclose agile sheep and declare boundary lines. They are consequently more substantial than the walls around arable fields in the valleys.

There are areas in Great Britain where stone is in short supply, for example southeast England. By happy accident these are usually the milder areas of the country where hedges grow easily, and these are an ideal option for agricultural fencing.

Some rock types naturally occur as easily handled pieces with regular sizes, shapes and angles. Other types require breaking or shaping before they can be used. A large stone can be manageable if it is square and flat, while a smaller stone will be awkward if it is angular with no obvious centre of gravity. Small, flat stones are easily handled and built into refined walls, but big boulders or flat slabs require more work and imagination.

Big pieces of rock, whether they are boulders or slabs of limestone, are most often used ‘as found’ – for example in single walls or as in the limestone feidín walls of western Ireland (seeChapter 6). If there is good mix of large and small stones, the larger stones are often spread out at regular intervals or set as upright slabs – ‘bookends’ for the smaller stones.

Wallers took advantage of any really large stones lying along the route of the wall. Early dry stone walling was a matter of building as much as possible, as quickly as possible. Wallers in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were usually paid by the yard. It was easy money for them if a huge boulder could be levered into position to make an instant yard or two. One relatively easy way to move a large boulder sitting on solid ground is to throw some smaller stones under it and push away with crowbars. The small stones reduce the contact between the boulder and the ground, and less contact means less friction and less energy required to move it.

High and Handsome

This 5ft (1.5m) enclosure wall most likely dates back to the early 1800s. It was built with stone pulled from the ground, gathered from the hillside or recycled from older structures. Large pieces were set on end and some were laid traced – that is, with their long edge along the wall. This does not create a weakness in this instance, as the size of the stones renders normal placement rules obsolete. The two ‘pillars’ in this vertical wall are unlikely to be gateposts – just two stones put into positions where they could best assist their smaller comrades. The face we see was built vertical; the other side of the wall is built with a batter and it narrows towards the top.

The lichen growth on the copestones confirms this is an old, undisturbed, wall. St Kilda, Scotland.

Chapter Two

Types of Rock, Sources and Quantities

Rock Types

To some extent the words ‘rock’ and ‘stone’ are interchangeable. Rock is a general term for part of the earth’s crust; a stone is part of that crust, broken down or shaped so that it can be used for building.

Most rock types have a high compressive strength, meaning they are difficult to crush when piled on top of each other. This makes them an ideal building material.

It is useful to understand a rock type, its origins and limitations, before working out how to break or shape it.

In general terms, there are three rock types, named for their method of origin.

Some rocks are formed from magma (molten rock under the earth’s crust) or lava (magma expelled by volcanic activity). Others are formed by the slow accumulation of sediments from the erosion of those rocks. The first of these are called igneous rocks, the second are sedimentary rocks. Both types were often subjected to extreme pressure or heat to form new rocks or broken, shattered varieties of the original. These are called metamorphic rocks.

Igneous Rocks

Igneous rocks are the oldest rocks, created from cooled lava or magma. Magma is molten rock under the earth’s crust. Lava is the same material pushed to the surface, commonly seen as a red-hot mass pouring down the side of a volcano. Magma cools more slowly under the earth’s crust, so there is plenty of time for crystals to form as it does so, producing rough-grained rocks such as gabbro or granites.

When magma is pushed above the earth’s crust, as lava, it produces finer-grained rocks such as basalt and andesite. It cools relatively quickly, so there is less time for crystals to form.

Volcanic activity also produces various forms of ash. Some types consolidate to form a soft rock called tuff, which is easily shaped and therefore a good building material.

Igneous rocks formed many of the mountainous areas in Scotland, northern England and Wales, and were duly incorporated into the sturdy mountain walls we see today.

Basalt columns, a common form of this igneous rock. It is dense, hard, brittle, and easily broken down into smaller pieces. Oregon, USA.

Sedimentary Rocks

Sedimentary rocks are the result of the build-up of sediments over millions of years. Silts, muds and biological debris accumulated on ocean bottom and lake beds, and were bound together by natural cements. In their purest form, sedimentary rocks appear with distinctly coloured layers, separated by bedding planes, where one thin line represents thousands of years of geological activity. The bedding plane can be a line of weakness: the rock is easier to split along these planes. These rocks are associated with gentler geological eras, when material had time to settle without disturbance.

Sedimentary rock types include limestone, coal, sandstone, siltstones, shale and conglomerates. Conglomerate rocks are types of sandstone with a substantial percentage of larger rounded or angular material within the silts; they sometimes look like a broken piece of concrete.

A limestone wall in western Ireland. This sedimentary rock is pried off the ground, or from outcrops, in relatively flat pieces. The walling style is derived from the rock – often large slabs laid on edge, with a rough cope, or built one stone thick, with the minimum of cutting or shaping. The Burren, Ireland.

Most sandstones have a parallel top and bottom edge. They are easily cut and shaped to make tightly coursed walls. The quarries in Caithness, northern Scotland, process a type of fine sandstone, a siltstone, which breaks out into big flagstones. Acres of quarry floor produce predictable thicknesses of stone, which are ideal for paving and, laid upright on edge, also make a good flagstone fence.

Could this sandstone cliff face be described as ‘solid rock’? The sedimentary beds are weather-beaten and eroded. Plants take advantage of splits and ledges. This could be an easily worked source of stone. Berriedale, Scotland.

Sedimentary rocks do not always consist of small-grained material. Beds of rougher rock sometimes lie between layers of finer grained rock. It depends on how the grains got there. Wind may have blown sands and dusts to form one layer, while water carried larger-grained material to sit on top of that. The upper stretches of ancient river beds have coarser material in their sediments because pebbles and large-grained sands fell to the bottom first. The smaller, lighter material was washed downstream to lakes and seas, to where it settled and was eventually compressed into fine-grained sandstones. The face of a sandstone quarry can resemble a marble cake.

Some sedimentary rocks, particularly sandstones and limestones, contain fossils. These are not found in igneous rock (because of its fiery origin), or were destroyed by the heat or pressures that created metamorphic rocks.

Metamorphic Rocks

Geology is an ongoing process. Metamorphic rock types were created after tremendous heat and pressure altered igneous and sedimentary rocks. They often have bands of colouring or crystals, brought about by the pressures that formed them. Types include schist, quartzite, gneiss, slate and marble. They are often granular and break into rough sheets.

Boulders

Any rock type, apart from possibly the softer rocks, can appear as boulders. In geological terms, a boulder is a piece of stone more than 10in (25cm) in diameter. In walling terms, we think of them as the large rounded stones found in river beds, floodplains and sand quarries.

A single or single-skinned dry stone dyke built from whole and split boulders. The spectacularly level top line shows what can be built from rough material, probably using nothing more complex than hammers and a length of string. Southwest Scotland.

Boulders began as pieces of bedrock torn from the larger mass. Their edges were then rounded by glacial and water action. Boulders retain the original characteristics of the rock they broke away from, so, for example, granite boulders are heavy and not easily split, while sandstone boulders will break along sedimentary planes.

Urbanite

This is a modern term applied to broken concrete, usually in the form of slabs. If it is a decent size with good faces, it can be used, like any flat stone, to make free-standing walls, retaining walls or paving. It can be very similar in appearance to conglomerate sandstone – a type of sandstone consisting of silts and large aggregate, all bonded together with natural cements such as calcite or quartz. The broken face of these slabs looks unattractive but they trim easily and weather quickly. Lime leaching from the concrete will also be beneficial to local plant growth.

An urbanite retaining wall on a corner. In the background we see one of the city’s many retaining walls, constructed from blocks of basalt. Seattle, USA.

If broken concrete is irregular and reasonably sized, it could be used for backing up retaining walls, especially if the stone for the face of the wall is expensive. Retaining walls should be wide and heavy; there is no need to spend money on expensive rock if it is placed at the back, invisible forever.

Sourcing Stone

The early wallers and dykers working on agricultural dry stone walls had a ready supply of stone along the route of the wall they were building. Stone cleared from the land was reformed into walls. If necessary, additional stone was brought in from nearby quarries or rock outcrops, or prised from stream beds. Using the local rock was always the best option, as carrying stone any distance was expensive and added considerably to the cost of a new wall.

Old buildings or old walls are a good source of building material. Stone from many old structures, including Hadrian’s Wall, found their way into dry stone walls during the eighteenth century, when a boom in wall construction followed the reorganization of land holdings and the agricultural revolution. Such recycling is not recommended nowadays. Some walls have historic value; some are archaeological evidence; some are a wildlife habitat. If it’s not yours, check with the owner before moving stone, even if it looks like an abandoned pile of field clearings that have lain there for 150 years.

This south-facing slope illustrates how much effort went into clearing land. The crofters (smallholder farmers) removed the stones to the edge of their ground, forming ridges and roughly built walls. The land between is remarkably clear of stone. Ullapool, Scotland.

Choose stone carefully, as not all types are suitable for walling. Some stone discolours after it is split and exposed to the air, and some weathers badly. Check out older walls made with a particular stone to see if, or how, it has changed with time.

Beware of stone from fire-damaged sites. Granite is degraded by heat; it crumbles and is no use for a load-bearing situation. Sandstone and thin-bedded rocks become stressed by heat and liable to spalling. These are useless for walling.

Using old stone is tempting because it is weathered and covered with moss and lichens. Unfortunately, this growth will lose colour and die if the stones become part of a new wall facing south, into the open sun.

If you are lucky, the stone comes from the ground the wall is built on. Digging the foundation for a new house frequently exposes enough stone for the garden walls.

The price of stone varies from place to place, based on many factors: the cost of extraction, the distance it travelled, whether it is on a pallet or loose. In general, the more diesel that went into producing it and transporting it, the more expensive it will be.

Many types of shale and limestone are fairly soft. They cannot take the stresses of tension or compression, especially when exposed to weathering, moisture and frost. This poor-quality rock is a type of fine-grained sandstone.

Palletized Stone

Palletized rock is the modern way to go. The stone comes in regular sizes and standard thickness. It is loaded onto a truck and can be transported anywhere, at a price – the cost reflects the time taken for sorting, cleaning and packaging.

Pallets are easy to get to most sites and work from. If the budget is there, have the pallets delivered as required, for each stage of construction. This means higher costs for transporting the stone to site, but is compensated for by easier site management and convenience.

A pallet of stone usually has four good faces of reasonably laid stone in the cube, typically about 3ft (1m) high. This gives a fair idea of how much wall could be built out of one pallet.

Quarries

Quarries are an obvious source for walling stone but they generally prefer to supply large-dimensional stone or smaller material for roads and concrete production – the relatively small amounts of stone required by wallers is small beer to most quarries. They won’t stockpile walling stone if it takes years to sell. The 10 tons of stone you ordered could arrive as fifteen lumps or as a load of gravel. It is best to check in with the local quarry, discuss what is needed and get a delivery of usable stone.

One good option is to hand-pick stone at a quarry (with their permission) and arrange delivery as required – the building stone should arrive first, then stone for copestones when the body of the wall is completed. This makes for easier site management.